Chapter 24

Environmental Disasters

Mark E. Keim

The author wishes to thank Braeden Benson, MPH, Hugh Green, MPH, and Casey Owens for their support provided in the literature search for this chapter. Dr. Keim reports no conflicts of interest related to the authorship of this chapter.

A disaster is “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses that exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources” (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction [UNISDR], 2009). A disruption that does not exceed a community's or society's capacity to cope is classified as an emergency. Emergencies and disasters are thus part of a continuum and differ only by their degree of severity.

A standard definition of disaster comes from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT) at the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, or CRED, at the Catholic University of Louvain, in Belgium. In order for an event to qualify as a disaster and be entered into EM-DAT, at least one of the following criteria must be fulfilled:

- Ten (10) or more people reported killed.

- One hundred (100) or more people reported affected.

- Declaration of a state of emergency.

- Call for international assistance.

Disaster consequences may include loss of life, injury, disease, and other negative effects on human physical, mental, and social well-being, together with damage to property, destruction of assets, loss of services, social and economic disruption, and environmental degradation. The severity of the consequences is referred to as the disaster impact.

Traditionally, disasters may be classified according to the causative agent or hazard (natural, technological, or complex). Natural disasters may be caused by either environmental hazards (including hydrometeorological and geological hazards) or biological hazards (pandemics, epidemics, and disease outbreaks). Technological (or man-made) disasters may be caused by environmental hazards (such as hazardous materials, fire, structural failure, and transportation accidents) or a complex mix of social, economic, and political hazards involving displacement (such as a forced mass migration originating in conflict or lack of food security) (see Table 24.1). Hybrid disasters are environmental disasters resulting from simultaneously occurring natural hazards and technological hazards. Examples include massive urban fires after both the 1906 San Francisco and 1995 Kobe earthquakes as well as the radiation disaster that followed the 2010 Fukushima earthquake and tsunami.

Table 24.1 A Typology of Environmental Disasters

| Natural | Technological | ||||

| Drought | Chemical | ||||

| Wildfires | |||||

| Hydrometeorological | Heat waves | Toxic | Radiological | ||

| Stormsa | |||||

| Floods | |||||

| Earthquakes | Fires | Nuclear | |||

| Geophysical | Landslidesb | Thermal | |||

| Volcanic eruptions | Explosions | ||||

| Tsunamis | Mechanical | ||||

| Transport accidents | |||||

aStorms include cyclones, tornadoes, windstorms, snow or ice storms, and dust storms.

bLandslides include debris flows, mud flows, volcanic lahars, and snow avalanches.

But few “natural” disasters are purely natural. For example, climate change—a result of human activities—is expected to increase hurricane intensity and flood frequency. Moreover, the way natural disasters unfold reflects an interplay of the physical event with human development patterns, societal adaptation (or maladaptation) to the physical environment, and vulnerability. According to this perspective, earthquakes, droughts, floods, and storms are natural hazards, but “unnatural disasters” are the deaths and damage that result from human acts of omission and commission. Every disaster is unique, but each exposes actions—by individuals and organizations at different levels—that, had they been different, would have resulted in fewer deaths and less damage (World Bank, 2010).

This complexity was recognized in 2005 with the global adoption of the Hyogo Framework for Action, an initiative led by the United Nations (UNISDR, 2007). The Hyogo Framework recognizes that all disaster risk (including natural, technological, and complex disasters) is a function of linked physical, social, economic, and environmental vulnerabilities. There is now international acknowledgment that disaster risk reduction must be systematically integrated into sustainable development, poverty reduction, and climate policy (Keim, 2008), and supported through bilateral, regional, and international cooperation, including partnerships.

Disaster risk is now recognized to occur as a result of the combination of population exposure to an environmental hazard, the conditions of human vulnerability that are present, and insufficient capacity or measures to reduce or cope with the hazard's negative consequences. Disaster risk management activities are therefore transitioning from a focus on reacting to specific categories of hazards and their associated effects (such as morbidity, mortality, and displacement) to an approach that also addresses the root causes of disaster-related losses (such as exposure, vulnerability, and capacity).

Scope of the Problem

During the past five decades (1964–2013), 19,555 environmental disasters (excluding epidemics, wars, and conflict-related famines) were reported to have killed 5.4 million people worldwide, affected 7 billion lives, and resulted in property damage exceeding US$2.7 billion, in time-adjusted 2014 dollars (CRED, 2015). Environmental disasters accounted for 93% (natural disasters 53% and technological disasters 40%) of the world's disasters during that time, eclipsing the 7% that were biological disasters (CRED, 2015).

Within the environmental disaster category, natural disasters accounted for 62% and technological disasters the remaining 38% (CRED, 2015). Specifically, transportation disasters represented 25% of environmental disasters, floods 15%, cyclones 9%, and earthquakes 5%. Hydrometeorological disasters accounted for the greatest burden among environmental disasters (65% of fatalities, 68% of costs, and 96% of all people affected) (CRED, 2015).

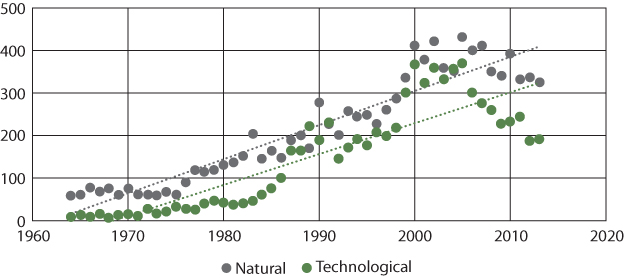

Nor was the pattern static from 1964 through 2013. The incidence of environmental disasters increased, with extreme weather disasters increasing much more rapidly than geological or biological disasters, affecting an increasing number of people, and causing increasingly large economic losses. However, there may be early indications of a downward trend for both natural and technological disasters since 2000 (Figure 24.1).

Figure 24.1 Annual Incidence of Natural and Technological Environmental Disasters—Worldwide, 1964–2013

Source: CRED, 2015.

Table 24.2 shows the ten deadliest environmental disasters during the years from 1964 to 2013. Of note, all ten were natural disasters occurring in low-income settings.

Table 24.2 The Ten Deadliest Environmental Disasters—Worldwide, 1964–2013

| Disaster type | Year | Location | Estimated fatalities |

| Drought | 1965 | India | 1,502,000 |

| Drought | 1983 | Ethiopia, Sudan | 450,520 |

| Tropical cyclone | 1970 | Bangladesh | 304,495 |

| Earthquake | 1976 | China | 276,994 |

| Earthquake | 2004 | Indonesia | 227,290 |

| Earthquake | 2010 | Haiti | 226,735 |

| Tropical cyclone | 1991 | Bangladesh | 146,297 |

| Tropical cyclone | 2008 | Myanmar | 140,985 |

| Drought | 1981 | Mozambique | 103,000 |

| Drought | 1973 | Ethiopia | 100,000 |

Source: CRED, 2015.

The Public Health Consequences of Environmental Disasters

Annual disaster frequency does not correlate closely with health impacts such as mortality, injury, and displacement, illustrating that disaster-related health effects reflect not just the number of events but also the complex interplay of exposures (quality, intensity, duration, etc.), vulnerability (demographics, comorbidity, education, socioeconomic status, etc.), and adaptive capacity (quality of preparedness resources, access to health care, community resilience, etc.).

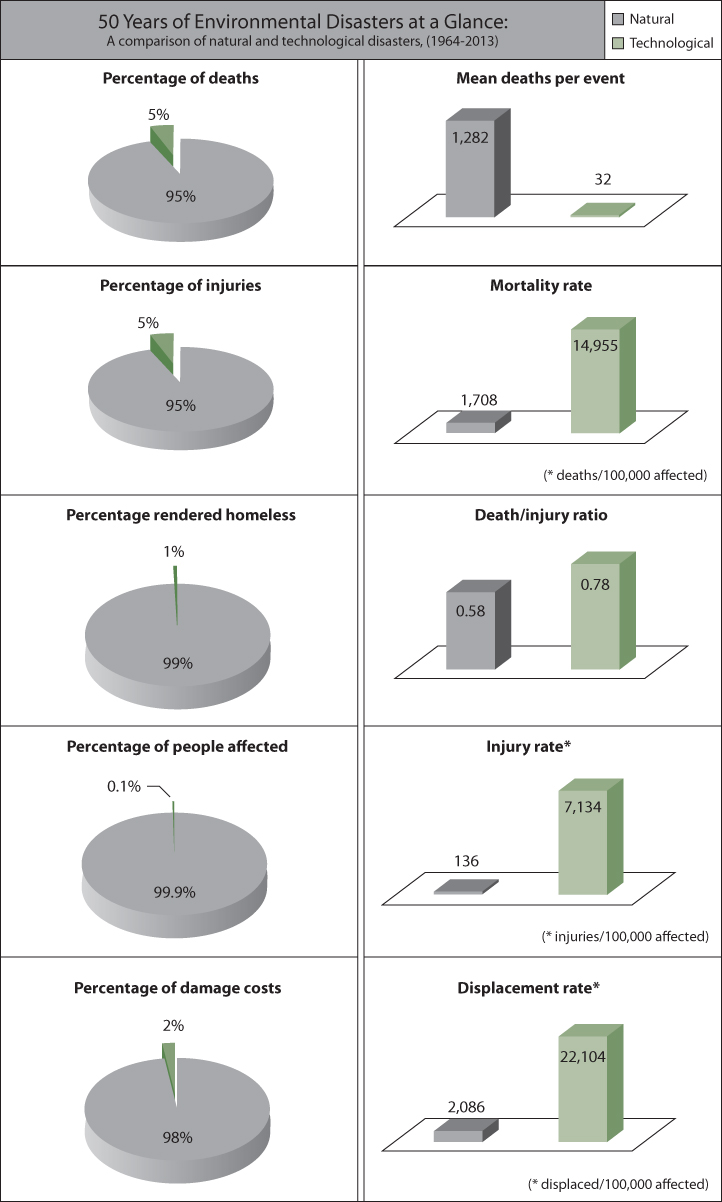

Figure 24.2 compares the health impacts of natural and technological disasters. While natural disasters represent 62% of environmental disasters, they account for far larger relative burdens of deaths, injuries, and other impacts (despite higher mortality and injury rates for technological disasters).

Figure 24.2 Comparison of the Public Health Impacts of Natural and Technological Disaster Events, 1964–2013

Source: CRED, 2015.

Mortality Associated with Environmental Disasters

Among environmental disasters over the past fifty years, natural disasters were responsible for the overwhelming majority of deaths, for three main reasons: natural disasters were nearly twice as frequent as technological disasters, natural disasters affected far more people per event than technological disasters, and the mean number of deaths per event was far greater for natural disasters (1,282) than that for technological disasters (32).

However, the mortality rate for technological disasters (14,955/100,000 affected people) is nearly nine times that of natural disasters (1,708). In addition, the mean number of deaths per injury for technological disasters (0.78) is 35% higher than that for natural disasters (0.58).

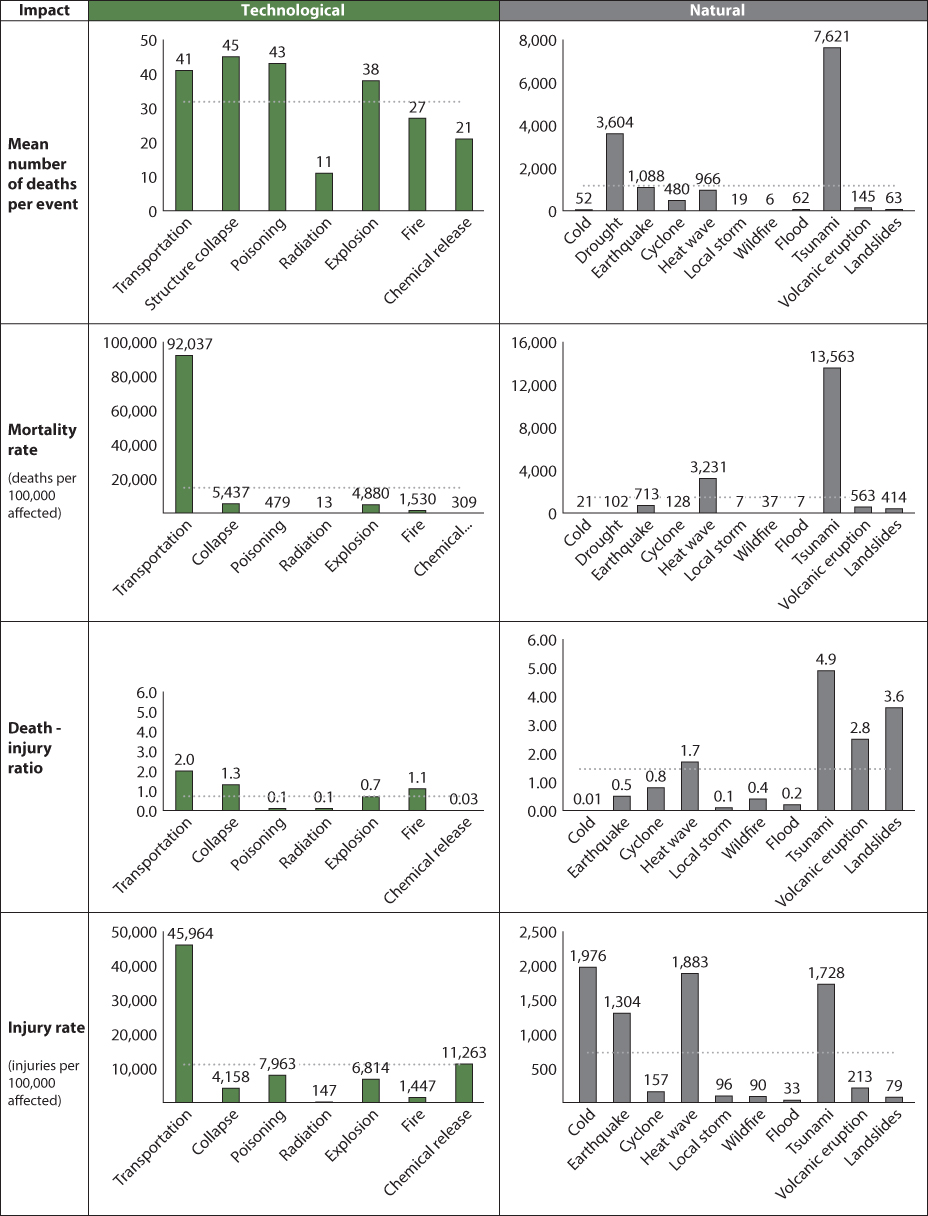

When considering individual types of environmental disasters, tsunamis have by far the highest mean number of deaths per event (7,621), followed by drought (3,604), earthquakes (1,088), and heat waves (966) (Figure 24.3). Structural collapse has the highest mean number of reported deaths per event among technological disasters (45), closely followed by poisonings (43) and transportation disasters (41) (CRED, 2015).

Figure 24.3 Key Public Health Impacts for Natural and Technological Disasters, 1964–2013

Note: The dotted line indicates the mean value for each set of values.

Source: CRED, 2015.

Transportation disasters have an extremely high mortality rate (92,037/100,000 affected people), meaning that 92% of people affected by transportation disasters worldwide lose their lives. This reflects the low survival from such incidents as aircraft crashes. Tsunamis have the second highest mortality rate among environmental disasters (13,563/100,000 affected people). The third and fourth highest mortality rates are associated with technological disasters: structural collapse (5,437/100,000 affected people) and explosions (4,880/100,000 affected people) (CRED, 2015) (Figure 24.3). A tragic example of structural collapse mortality, emphasizing the vulnerability of poor nations, was the Rana Plaza disaster of 2013, which killed over 1,000 workers in Bangladesh; this is described in Chapter 21.

Tsunamis have the highest death to injury ratio of all environmental disasters. During tsunami disasters, there were 4.9 times more reported deaths than injuries. Other environmental disasters with a high number of deaths relative to injuries include landslides (3.6 deaths per injury), volcanic eruptions (2.5). transportation accidents (2), heat waves (1.7), structural collapse (1.3), and (urban) fires (1.1) (Also see Table 24.3.)

Table 24.3 Major Causes of Death During Environmental Disasters

| Natural | Technological | |||

| Drought | Malnutrition | Chemical release | Poisoning, asphyxia | |

| Wildfires | Asphyxiation, burns, toxic exposures | Poisonings | Poisoning | |

| Heat waves | Heat stroke, exacerbations of cardiovascular disease | Nuclear | Traumatic injury, burns, radiation illness | |

| Storms | Drowning, traumatic injury | |||

| Floods | Drowning | Radiological | Radiation illness | |

| Earthquakes | Traumatic injury, asphyxia | Fires | Burns, asphyxia | |

| Landslides | Traumatic injury, asphyxia | Explosions | Traumatic injury, burns | |

| Volcanic eruptions | Traumatic injury, burns, toxic exposures | Transportation accidents | Traumatic injury, burns, drowning | |

| Tsunamis | Drowning, traumatic injury | Structural collapse | Traumatic injury, asphyxia | |

| Cold weather | Hypothermia | |||

Sources: Bailey & Walker, 2007; Bertazzi, 1989; Binder, 1989; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1983, 1993, 1998, 2002; Chowdhury et al., 1992; Cronin & Sharp, 2002; Duclos, Sanderson, Thompson, Brackin, & Binder, 1987; Floret, Viel, Mauny, Hoen, & Piarroux, 2006; Guha-Sapir & van Panhuis, 2005; Hull, Grindlinger, Hirsch, Petrone, & Burke, 1985; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, 2007; Keim, 2002, 2008; Lillibridge, 1997; Malilay, 1997; Mehta, Mehta, Mehta, & Makhijani, 1990; Sanderson, 1992, 1997; Sattler et al., 2002; Toole, 1997; World Health Organization, 2009.

Morbidity Associated with Environmental Disasters

Injury

Overall, the injury rate (number of injuries/100,000 affected) for natural disasters (144/100,000) is nearly the same as that for technological disasters (137/100,000). Among specific types of disasters, technological disasters show the highest injury rates: transportation accidents (45,964/100,000), chemical releases (11,263/100,000), poisoning (7,963/100,000), explosions (6,814/100,000), and structural collapse (4,158/100,000). The highest injury rates reported for natural disasters are for cold weather (1,976/100,000), heat waves (1,883/100,000), tsunamis (1,728/100,000), and earthquakes (1,304/100,000). Most injuries associated with technological disasters occur at the time of disaster impact (when populations are in direct contact with the disaster hazard). However, in the case of natural disasters, the timing of injuries is often bimodal. In these circumstances, injuries occur not only in the impact phase but also during the postimpact recovery phase, as survivors work to clean up or rehabilitate disaster damages. For example, in a study of the 2014 China earthquake, 24% of the 2,010 injury victims studied sustained their injuries during evacuation after the impact phase, when seismic activity had receded (Zhang et al., 2014).

Communicable Disease

While members of the public and the media frequently fear infectious disease outbreaks after disasters, such outbreaks are actually quite rare. The risk of an epidemic after geophysical disasters is considered negligible (Floret et al., 2006). Floods and cyclones are in rare circumstances followed by outbreaks of infectious disease, mostly in low-income nations where baseline infrastructure and recovery capabilities are inadequate. In these settings, disasters may exacerbate diseases that are normally endemic, such as acute respiratory infections, leptospirosis, dengue fever, typhoid, malaria, and cholera. The rare outbreaks of posthurricane infectious disease in high-income countries have consisted of self-limiting gastrointestinal disease, dermatological infections, and respiratory infections. Flooding may also result in episodes of near-drowning and pulmonary aspiration of floodwater resulting in pneumonia. Near-drowning is also common in tsunamis and is associated with aspiration pneumonia or tsunami lung, a necrotizing pneumonia notable for flora commonly associated with sea water aspiration (Allworth, 2005).

Wound and respiratory infections are common after tsunamis and earthquakes and are often associated with a high mortality rate. In a study following the 2014 earthquake in China, lung infections were the most common infection among hospitalized patients (60 individuals, or 37.7%), followed by skin and soft tissue infections (26, 16.4%) and secondary open wound infections (25, 15.7%) (Zhang et al., 2014). Earthquake-related pneumonitis has been associated with the inhalation of debris dust, particularly concrete.

Noncommunicable Disease

Environmental disasters such as earthquakes, floods, and storms may be associated with exacerbation of chronic diseases such as mental illness, cardiovascular disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In some cases these effects are nonspecific and may relate to post-traumatic response; for instance, the 2011 earthquake in Japan was followed by increases in new onset, acute coronary syndrome and exacerbations of congestive heart failure (Nozaki et al., 2013). Chronic disease exacerbations may also reflect loss of medications or interruptions in ongoing medical care. Finally, specific effects of some disasters may be operative in cases such as exacerbations of chronic obstructive lung disease and asthma from smoke inhalation during wildfires and volcanoes and exacerbations of respiratory and cardiovascular disease during heat waves.

Behavioral health effects are among the most debilitating long-term health outcomes of environmental disasters, and in some cases represent the largest health burden (Davidson & McFarlane, 2006; Halpern & Tramontin, 2007; Neria, Galea, & Norris, 2009). Research conducted several months after Hurricane Katrina, for example, showed that 49.1% of those surveyed in New Orleans, and 26.4% in other hurricane-affected areas, suffered from anxiety-mood disorders as defined in DSM-IV, of which half or more were post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Galea et al., 2007). According to a study two years after the hurricane, the prevalence of PTSD and depression had actually increased (Kessler et al., 2008). Disaster epidemiology has documented similar outcomes—in some cases accompanied by increases in suicide, substance abuse, and domestic violence—in most cultures studied and following widely varying disasters: floods, dam collapses, heat waves, tsunamis, landslides, and wildfires. Risk factors for depression and/or PTSD vary but often include female sex, childhood, low levels of social capital or social support, physical injury, property loss, witnessing people suffering or dying during the disaster, loss of family members, relocation or displacement, history of psychiatric illness, and not having insurance. Interestingly, exposure to news coverage during and after the disaster, especially when graphic or violent images are shown, is a risk factor in some studies. Protective factors include personal resiliency, prompt provision of recovery resources, high levels of social capital, and the ability to keep communities intact. These findings suggest a variety of adaptation strategies to protect postdisaster mental health (King, Reifels et al., 2013; Silove & Steel, 2006; Ursano, Fullerton, Weisaeth, & Raphael, 2011; Burkle, Walsh, & North, 2015), including strengthening predisaster social support, providing post-disaster mental health and psychosocial services, targeting at-risk groups, paying attention to the content and framing of news coverage, and ensuring prompt implementation of recovery assistance such as insurance compensation for property loss.

Toxic Exposures

There is a potential for exposure to hazardous materials during the impact and also the cleanup phase of environmental disasters. During floods, industrial and stored household chemicals may be mobilized. For example, in 1999, landslides in Venezuela destroyed parts of the port facilities used to store hazardous materials. These chemicals were inundated by the debris flow and came dangerously close to causing an explosion with the potential to affect 80,000 nearby residents, and also closed the nation's largest airport and second largest seaport (Keim, Humphrey, & Dreyfus, 2000; “Venezuela Seeks Contractors…,” 2000). Other toxic exposures include mold, a potential public health problem following major floods and hurricanes, and carbon monoxide, which becomes a hazard when disaster-affected populations lose electrical power and improperly use carbon monoxide–emitting fuel sources in poorly ventilated spaces.

Malnutrition

Generalized food shortages severe enough to cause nutritional problems usually do not occur after disasters other than drought, but may arise in low-income nations in two ways. First, food stock destruction within the disaster area may reduce the absolute amount of food available, and/or second, disruption of distribution systems may curtail access to food, even when there is no absolute shortage. Throughout human history the most feared impact of drought has been a shortage of food. During the 2011 floods in Southeast Asia, food security became a major issue as it became difficult to deliver food supplies to flood-affected areas (Kim, 2006). In addition, severe damage to agricultural land and livestock affects those who rely on these forms of food production, with main food crops often being severely damaged, along with losses in livestock and poultry.

Displacement

Beyond the morbidity that results directly from disaster-related environmental hazards, much of the secondary morbidity is associated with displacement. All environmental disasters can interfere with access to adequate shelter, water, sanitation, hygiene, health care, nutrition, security, public services, and/or utilities among affected populations. These factors have a significant influence on morbidity following a disaster.

Homeless populations are more vulnerable to continued environmental exposures as well as to social disruption and psychosocial stress. Displaced populations and those suffering the loss of public utilities also risk loss of safe food and water and experience inadequate hygiene and sanitation. People who engage in postdisaster cleanup activities risk injuries such as falls, electrocutions, and equipment (e.g., chainsaw) injuries.

Displacement from homes carries substantial potential for psychosocial impacts. The long-term effects of displacement on psychological health may outweigh other illness or injury related to natural disasters (Fussell & Lowe, 2014; Neria, Galea & Norris, 2009).

Natural and technological disasters have roughly similar displacement rates, at about 2% of those affected. The environmental disasters with the highest displacement rate are radiation disasters (48,250/100,000 affected), an outcome driven largely by two large-scale radiation disasters during the 1964 to 2013 period, at Chernobyl and Fukushima. Following close behind are two technological disasters—explosions (36,934/100,000) and fires (36,109/100,000)—as well as displacements due to natural disasters, most notably, tsunamis (35,222/100,000) and landslides (30,835/100,000) (CRED, 2015). After two major disasters in 2010—the flood in Pakistan and earthquake in Haiti—millions of households in each country were displaced. A year later, displacement persisted among 53% of affected households in Pakistan, and among 39% in Haiti (Weiss, Kirsch, Doocy, & Perrin, 2014).

Disaster Risk and Its Determinants

Risk is the probability that something will cause injury or harm. While risk can rarely be completely eliminated, it can be managed. Risk management is activity directed toward assessing, controlling, and monitoring risks. In risk management, evidence on risk factors is collected and analyzed, risks in particular contexts are assessed, and control measures are implemented, using standard strategies. The risk of disaster-related morbidity and mortality is a complex function of factors both extrinsic and intrinsic to the individual.

Extrinsic Factors Affecting Disaster Risk

Extrinsic disaster risk factors relate to exposure and capacity. Exposure is defined as contact with a potentially dangerous hazard, such as wind from tornadoes, water from floods, or heat from heat waves. Capacity is the combination of all external resources that can be deployed to minimize morbidity and mortality following exposure. Capacity includes four major categories of resources: economic resources (e.g., occupation, income, savings, and health insurance); material resources (e.g., emergency equipment and supplies, food and water, medicines, health care, transportation, shelter, and quality of housing and the built environment); behavioral resources (e.g., emergency plans, mutual aid agreements, memoranda of understanding, and communication plans); and sociopolitical resources (e.g., social support and capital, political representation, and formal and informal communication networks).

Intrinsic factors Affecting Disaster Risk

Intrinsic risk factors for disaster-related morbidity and mortality include attributes related to human vulnerability. Vulnerability includes four major categories of attributes: demographics (e.g., age, gender, and family position); education and personal experience (e.g., educational level and disaster training); race, language, and ethnicity (e.g., minority status in the affected population and language barriers); and health status (e.g., chronic illness, physical disability, malnutrition, mental illness, and dependence upon life-sustaining treatment).

Epidemiological studies following disasters have pinpointed some of these risk factors. One of the best-known examples is a study of the 1995 Chicago heat wave (Klinenberg, 2002). During that disaster, mortality was elevated among socially isolated, elderly, inner-city African American populations; other risk factors included low-quality housing and lack of air conditioning. In general, poverty may be the single most important risk factor for vulnerability to all environmental disasters (Thomas, Phillips, Lovekamp, Fothergill, & Toole, 2013). For example, as discussed in Chapter 11, dangerous facilities such as chemical plants, with their attendant risk of accidents, are disproportionately concentrated in poor and/or minority communities (Elliott, Wang, Lowe, & Kleindorfer, 2004). Similarly, the overwhelming majority of casualties in the Bhopal, India, disaster occurred among extremely poor day laborers (Mehta, 1990).

Managing Disaster Risk

Disaster risk management applies the general principles of risk management to disasters. Risk management has standard operational categories, including risk avoidance, risk reduction, risk transfer, and risk retention. Emergency managers think in terms of a different set of categories: prevention, mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. And public health professionals, with a prevention orientation, often think in terms of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. These three frameworks align well with each other, as shown in Figure 24.5.

Disaster risk management is a comprehensive approach that entails developing and implementing strategies for each phase of the disaster life cycle. The emphasis on a life cycle approach, beginning well before a disaster and continuing through the aftermath, is important in all disasters. While the depiction of disasters as cyclical may seem to imply that disasters are inevitable, this is not the case. The goals of risk avoidance and risk reduction are to avert disasters and retained risk, thus breaking the disaster cycle. The ultimate goal of disaster risk management is to break the disaster life cycle. A key aspect of meeting this goal is building resilience, as discussed in Text Box 24.1.

Anticipation, Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment, and Planning

For all of the frameworks shown in Figure 24.5, anticipation, recognition, risk assessment, and planning come first. Ideally, disaster risk management is based on a prioritization process. Once risks have been identified, they are assessed in terms of the potential severity of loss and the probability of occurrence. The risks likely to incur the greatest loss and having the greatest probability of occurrence are addressed first, and risks presenting a potentially lower loss and lower probability of occurrence are handled in descending order. In practice the prioritization process can be very difficult.

Risk Avoidance and Prevention

Risk avoidance, in risk management parlance, corresponds to primary prevention in both public health and emergency management terms. Primary prevention seeks to prevent the disaster hazard exposure from ever occurring. For example, floodplain management may prevent flood disasters altogether, and logging restrictions on unstable hillsides may prevent landslides.

Much of the approach to primary prevention of technological disasters is based on regulation of industrial and commercial practices, including the manufacture, storage, transport, and utilization of hazardous materials as well as the promotion of safe practices in the construction and transportation industries.

Risk Reduction

Risk reduction involves methods that reduce the likelihood of occurrence and/or the severity of the loss. This corresponds to secondary prevention, the general public health strategy that aims to detect a hazard early to control its advance and to reduce the resulting health burden—or in emergency management terms, preparedness, and mitigation. Risk reduction activities seek to prepare for and mitigate the health effects of disasters that cannot be prevented, using strategies that address the root causes of disaster-related morbidity and mortality (i.e., exposure, vulnerability, and lack of capacity).

Mitigation measures reduce population vulnerability by reducing exposure to disaster hazards. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA; 2013) identifies four types of mitigation measures: local plans and regulations, structure and infrastructure projects, natural system protection, and education and awareness programs. Local plans and regulations may include a wide range of strategies. For example, hazard source control aims to reduce the probability or magnitude of an event at the source—say, by limiting the quantity of chemicals stored on-site at a water treatment plant—and land-use practices limit hazard exposure by minimizing development in risky areas, such as by restricting building in floodplains or in landslide-prone areas. Structure and infrastructure projects might include community protection works that interrupt hazard transmission—say, by placing berms around chemical storage tanks to contain leaks—or building construction practices that limit physical vulnerability through structural means, such as seismic design (in earthquake-prone areas) or placing generators on the upper floors of hospitals (in flood-prone areas). Natural systems protection might include sediment and erosion control and stream corridor restoration or wetland restoration to help protect against flooding (while providing other kinds of ecosystem services, as described in Chapter 2). Education and awareness programs inform and educate citizens and decision makers about hazards and potential ways to mitigate them. Examples include local hurricane evacuation or heat wave preparedness training, or participation in national programs such as StormReady or Firewise Communities. For other kinds of disasters, especially those that emerge slowly, other kinds of mitigation measures are used, such as providing drought-tolerant seeds to farmers in arid areas.

Preparedness is closely linked to mitigation, as part of risk reduction. Preparedness implies a behavioral approach focused on actions taken in advance of a disaster in order to reduce its impact. This reduces population vulnerability.

Populations at risk for disasters face a vast range of hazards within a nearly infinite set of scenarios. This unpredictability is poorly suited to scenario-based approaches to risk management. While the hazards that cause disasters vary greatly, the potential public health consequences and subsequent needs of those affected are far more consistent across disasters. For example, warfare, chemical releases, floods, hurricanes. and earthquakes all displace people from their homes. These hazards require the same sheltering capability with only minor adjustments based on the rapidity of onset, scale, duration, location, and intensity. Regardless of the hazard, disasters can be seen as causing fifteen public health consequences that are addressed by thirty-two categories of public health and medical capabilities (Table 24.4) (Keim, 2006). All-hazards preparedness, accordingly, is the idea that common capabilities can serve well in a variety of disaster situations, with variation based more on severity of the disaster (scale or degree of impact) than on disaster type.

Table 24.4 Public Health Consequences and Capabilities Associated with All Disasters

| Public health consequences | Public health capabilities |

| Common to all consequences | Resource management Mental health services Reproductive health services Social services Occupational health and safety Business continuity |

| Deaths | Mortuary care Social services Mental health services |

| Illness and injuries | Health services Injury prevention and control Epidemiology Disease prevention and control |

| Loss of clean water | Access to safe water |

| Loss of shelter | Shelter and settlement Social services Security |

| Loss of personal and household goods | Replacement of personal and household goods |

| Loss of sanitation and routine hygiene | Sanitation, excreta disposal, and hygiene promotion |

| Disruption of solid waste management | Solid waste management |

| Public concern for safety | Risk communication Public information Security |

| Increased pests and vectors | Pest and vector control |

| Loss or damage of health care system | Health system and infrastructure support |

| Worsening of chronic illnesses | Health services |

| Food scarcity | Food safety, security, and nutrition |

| Standing surface water | Public works and engineering |

| Toxic exposures | Risk assessment Population protection Health services Hazmat emergency response Occupational health and safety |

Source: Adapted from Keim, 2006.

The 11 E's of public health preparedness (Text Box 24.2) offer an easy way to summarize and recall those capabilities commonly involved in public health preparedness.

Disaster Risk Transfer

Disaster risk transfer includes such mechanisms as insurance contracts and risk retention pools. By purchasing an insurance contract, people are able to transfer and share risk across a large population. Risk retention pools are similar; but instead of assessing premiums in advance, these pools assess losses across all members of the group once they occur.

Disaster Response

Disaster risk retention is a risk management term that means accepting the loss when it occurs and focusing on response and recovery. All residual risks that are not avoided or transferred are retained by default. This corresponds to the public health concept of tertiary prevention—seeking to prevent additional harm once an adverse event has occurred. This stage of prevention aims to reduce morbidity, avoid complications, and restore function. In the emergency management disaster cycle, this corresponds to the response and recovery phases (Keim, 2008).

Disaster response, sometimes called disaster relief, is predominantly focused on immediate and short-term needs. Response usually includes those actions immediately necessary to remove the affected population from ongoing exposure or risk of harm. The emergency operations plan is central to emergency management. Emergency operations plans describe who will do what—as well as when they will do it, with what resources, and by what authority—before, during, and immediately after an emergency (FEMA, 2010). In the United States the National Response Framework (NRF) establishes guiding principles to enable all levels of domestic response partners to prepare for and provide a unified national response to disasters and emergencies. Public health has a well-defined role under Emergency Support Function No. 8 (ESF-8) of the NRF, which addresses all public health and medical issues.

The Incident Command System (ICS) is a standardized, on-scene, all-hazard incident management protocol under the NRF. It is based on a flexible, scalable, common response framework designed to facilitate people's working together effectively. The National Incident Management System (NIMS), in turn, is a form of incident command system used in the United States to provide a systematic, proactive guidance to departments and agencies at all levels of government, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector in working seamlessly together before, during, and after emergencies.

Immediately after the disaster impact, rapid needs assessments are conducted in order to identify any gap between the health needs of an affected community and the available resources. In addition to performing health surveillance, public health practitioners are often involved in decisions regarding housing and public safety, assist in delivery of health care, perform food safety and water quality inspections, and assess sanitation and hygiene in shelters. The demands for environmental health services and consultation are quite high during and after natural disasters. Public health practitioners also become involved in health risk assessments and technical assistance related to any suspected hazardous material exposures after an environmental disaster, such as chemical spills.

Health and risk communication is essential before and after disaster impact (e.g., to publicize protective behaviors that can help to prevent drowning or heat illness). Injuries such as electrocutions, burns, and carbon monoxide poisonings are examples of disaster-related morbidity that can be prevented through public awareness and health education. Communication principles and strategies are discussed in Chapter 28.

Recovering from the Public Health Impact of Environmental Disasters

Rehabilitation and reconstruction begin soon after the emergency phase has ended, and should be based on preexisting strategies and policies that facilitate clear institutional responsibilities for recovery action and enable public participation. The division between the response stage and the subsequent recovery stage is not clear-cut. Some response actions, such as the supply of temporary housing and water supplies, may extend well into the recovery stage.

Recovery programs, coupled with the heightened public awareness after a disaster, also afford a valuable opportunity to develop and implement disaster risk reduction measures and to apply the build back better principle.

Long-term recovery from the public health impact of major disasters can take years to achieve (as described in Text Box 24.3). Additional financial, health, and emotional costs may continue long after basic utilities and shelter have been reinstated. The disaster recovery phase may also offer a window of opportunity for improving risk reduction strategies, such as preparedness and mitigation efforts.

Summary

Environmental disasters represent a significant health threat worldwide. The public health impacts of environmental disasters include deaths, injuries, communicable and noncommunicable diseases, toxic exposures, and a diminished ability to maintain adequate shelter, water supplies, sanitation, hygiene, public services, and utilities. In the environmental disasters of the past fifty years, natural disasters have greatly exceeded technological disasters in public health impacts, because of their greater frequency and scale. However, technological disasters result in greater morbidity and mortality among affected populations. While the hazards that cause disasters may vary greatly, the potential public health consequences and subsequent public health and medical needs of the population do not. A comprehensive approach to disaster risk management addresses not only the adverse health effects caused by disasters but also the root causes of these health effects.

Key Terms

- affected people

- People requiring immediate assistance during a period of emergency, including both the injured and the homeless.

- all-hazards preparedness

- The idea that common capabilities can serve well in a variety of disaster situations, with variation based more on severity of the disaster (scale or degree of impact) than on disaster type.

- capacity

- The combination of all the strengths, attributes, and resources available in a community, society, or organization that can be used to minimize morbidity and mortality following exposure to a hazard.

- chemical releases

- Disasters caused by the uncontrolled release of a hazardous chemical.

- cold weather

- A disaster can be caused by what is usually an abrupt onset of uncharacteristically cold weather, which may also be associated with loss of public utilities.

- consequences

- In a disaster, adverse conditions caused by the disaster (as compared to impact, a measure of the degree of such consequences).

- cyclones

- Weather phenomena featuring a central region of low pressure surrounded by air flowing in an inward spiral and generating maximum sustained wind speeds of 74 mph or more. Tropical cyclones—those that form over warm water—are called hurricanes in the Atlantic basin and the western Coast of Mexico, typhoons in the western Pacific, and cyclones in the Indian Ocean and Australasia.

- damage

- Disaster-related loss of individual and societal assets or functionality, often expressed in terms of economic indicators.

- disaster

- A “serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society causing widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses that exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources” (UNISDR, 2009).

- disaster risk

- The potential losses, in lives, health status, livelihoods, assets, and services, that c a particular community or a society could suffer during a disaster over some specified future time period.

- droughts

- Disasters caused by a protracted period of deficient precipitation.

- earthquakes

- Disasters caused by a sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust that creates seismic waves resulting in violent shaking of the ground.

- emergency operations plan

- A plan, drawn up in advance, that describes who will do what, when, with what resources, and by what authority before, during, and immediately after an emergency.

- environmental disasters

- Disasters that occur as a result of the presence of either naturally occurring or human-generated health hazards resulting in the creation of environments that are potentially harmful to human health.

- explosions

- Disasters caused by a violent expansion of energetic materials in which the energy is transmitted outward as a shock wave. Causes may be intentional or unintentional in origin.

- exposure

- Contact with a potentially dangerous hazard. Also, the people, property, systems, or other elements present in hazard zones that are thereby subject to potential losses.

- fires

- Disasters caused by fires located in urban areas.

- floods

- Disasters caused by the overflow of water into areas not normally submerged or by a stream that has broken its normal confines or by water that has accumulated due to lack of drainage.

- hazard

- A dangerous phenomenon, substance, human activity, or condition that may cause loss of life, injury, or other negative health impacts; property damage; loss of livelihoods and services; social and economic disruption; and/or environmental damage.

- heat waves

- Disasters caused by higher than normal ambient temperatures, of sufficient extremes to create a safety hazard for populations exposed to the heat.

- hybrid disasters

- Disasters caused by a mixture of nearly simultaneously occurring natural and technological hazards, such as fires and hazardous material releases occurring after earthquakes.

- impact

- The degree of severity associated with disaster consequences, often measured in terms of number of fatalities and injuries; functionality of critical facilities and community lifelines; property and environmental damage; economic, social, and political disruptions; and size of the area or number of people affected. (Impact is often erroneously used to mean consequences.)

- Incident Command System (ICS)

- A standardized, on-scene, all-hazard incident management protocol under the NRF.

- injury

- An adverse health condition, including the physical injuries, trauma, or illnesses requiring medical treatment as a direct result of a disaster.

- landslides

- Disasters resulting from the sudden mass movement of ground surface material caused by gravity.

- National Incident Management System (NIMS)

- A form of incident command system used in the United States to provide systematic, proactive guidance to departments and agencies at all levels of government, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector.

- National Response Framework (NRF)

- In the United States, the guiding principles of unified national response to disasters and emergencies. The NRF defines specific emergency support functions, including Emergency Support Function No. 8 (ESF-8), which addresses public health and medical issues.

- natural hazards

- Natural processes or phenomena that may cause loss of life, injury or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage.

- poisoning

- Ingestion or inhalation of toxic substances. Poisoning can constitute a disaster when it occurs on a large scale, generally due to contamination of food products or exposure to commercial products containing hazardous materials.

- radiation disasters

- Disasters caused by population exposure to high-energy radioactive materials.

- recovery

- In the disaster context, the restoration, and improvement where appropriate, of facilities, livelihoods, and living conditions of disaster-affected communities, including efforts to reduce disaster risk factors.

- resilience, disaster

- In the disaster context, the ability of nations, localities, institutions, communities, families, and individuals to absorb and recover from shocks such as earthquakes and heat waves, and to maintain living standards while adapting and transforming to long-term changes and uncertainty. Greater reslience connotes reduced vulnerability.

- risk

- The probability that something will cause injury or harm.

- risk acceptance

- A risk management technique based upon the notion of “acceptable risk”—the level of potential losses that a society or community considers acceptable given existing social, economic, political, cultural, technical, and environmental conditions.

- risk avoidance

- A risk management technique aimed at the elimination of hazards, activities, and exposures that can cause potential losses

- risk management

- Systematic activity directed toward assessing, controlling, and monitoring risks to minimize potential harm and loss.

- risk reduction

- Risk management technique aimed at reducing the likelihood that a risk will occur.

- risk retention

- Risk management technique aimed at accepting the loss when it occurs (e.g., acceptable risk) and focusing on response and recovery.

- risk transfer

- Risk management technique aimed at shifting particular risks from one party to another, so that one party will obtain resources from the other after a disaster occurs, in exchange for social or financial benefits.

- storm

- Any disturbed state of Earth's atmosphere, strongly implying severe weather. It may be marked by strong wind, thunder and lightning, heavy precipitation, and/or wind transporting some substance through the atmosphere (such as dust, snow, rain, or hail).

- structural collapse

- A disaster resulting from the collapse or failure of man-made structures, such as buildings, large storage facilities, dams, and levees.

- technological hazard

- A hazard originating from technological or industrial conditions, including accidents, dangerous procedures, infrastructure failures, or specific human activities, that may cause loss of life, injury, illness or other health impacts, property damage, loss of livelihoods and services, social and economic disruption, or environmental damage.

- tornado

- A violently rotating column of air extending between, and in contact with, a cloud and the surface of the earth. Tornadoes are smaller and briefer in duration than cyclones but have higher wind speeds.

- transportation disasters

- Disasters associated with means of air, ground, or water mass transportation, usually associated with malicious intent, human error, mechanical failure, or hazardous environmental conditions.

- vulnerability

- Having characteristics and circumstances that make a community or individual, or a system or asset, susceptible to the damaging effects of a hazard.

- wildfires

- Disasters caused by an uncontrolled fire in a rural or wilderness area of combustible vegetation.

Sources: A number of these definitions are based on UNISDR, 2009, or CRED, 2014.

Discussion Questions

- What are three major natural and technological hazards that currently place your community at risk for disaster? What are the health risks presented, and how would you describe the community's preparedness?

- Which groups of people and which facilities in your community are most vulnerable to the potential disasters you identified in Question 1? What characteristics make them vulnerable?

- While the scale and the frequency of natural disasters are greater than those of technological disasters, technological disasters are far more hazardous when considering risk of morbidity and mortality among those populations affected. Why might this be?

- The relationship between disasters and communicable diseases is frequently misconstrued. What are some of the reasons why this might be the case?

- Who in your community is responsible for disaster planning and response? What plans and arrangements do they have in place, and how would you assess these plans and arrangements? Would you make any recommendations for improvement?

- Disaster preparedness and response are fundamentally based in communities, and the most prepared, resilient communities enjoy many co-benefits. What, in some detail, are the various implications of this statement for your community?

- Disaster epidemiology is essential to understanding the health aspects of disasters, but this field of epidemiology confronts some unique methodological challenges. What are some of these challenges? What suggestions do you have for ways to overcome them?

References

- Allworth, A. (2005). Tsunami lung: A necrotizing pneumonia in survivors of the Asian tsunami. Medical Journal of Australia, 182(7), 364.

- Bailey, G., & Walker, J. (2007). Heat-related disasters. In D. E. Hogan & J. L. Burstein (Eds.), Disaster Medicine (2nd ed., pp. 256–265). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Bertazzi, P. (1989). Industrial disasters and epidemiology. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 15, 85–100.

- Binder, S. (1989). Deaths, injuries and evacuations from acute hazardous materials releases. American Journal of Public Health, 79, 1042–1044.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1983). Outbreak of diarrheal illness associated with a natural disaster—Utah. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 32(50), 662–664.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1993). Injuries and illnesses related to Hurricane Andrew—Louisiana, 1992. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 42, 242–243, 249–251.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1998). Needs assessment following Hurricane Georges—Dominican Republic. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 48, 93–95.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2002). Tropical Storm Allison rapid needs assessment—Houston, Texas, June 2001. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 51(17), 365–369.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. (2015). EM-DAT: The international disaster database. Brussels: Ecole de santé publique, Université catholique de Louvain. Retrieved from http://www.emdat.be

- Chowdhury, M., Choudhury, Y., Bhuiya, A., Islam, K., Hussain, Z., Rahman, O.,…Bennish, M. (1992). Cyclone aftermath: Research and directions for the future. In H. Hossain, C. P. Dodge, & F. H. Abed (Eds.), From crisis to development: Coping with disasters in Bangladesh (pp. 101–133). Dhaka: University Press.

- Cronin, S., & Sharp, D. (2002). Environmental impacts on health from continuous volcanic activity at Yasur (Tanna) and Ambrym, Vanuatu. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 12, 109–123.

- Davidson, J. R., & McFarlane, A. C. (2006). The extent and impact of mental health problems after disaster. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(Suppl. 2), 9–14.

- Duclos, P., Sanderson, L., Thompson, F., Brackin, B., & Binder, S. (1987). Community evacuation following a chlorine release, Mississippi. Disasters, 11(4), 286–289.

- Elliott, M., Wang, Y., Lowe, R., & Kleindorfer, P. R. (2004). Environmental justice: Frequency and severity of US chemical industry accidents and the socio-economic status of surrounding communities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58, 24–30.

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2010). CPG 101, developing and maintaining emergency operations plans, version 2. Retrieved from http://www.fema.gov/media-library/assets/documents/25975

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2013). Local mitigation planning handbook. Retrieved from http://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/20130726-1910-25045-9160/fema_local_mitigation_handbook.pdf

- Floret, N., Viel, J., Mauny, F., Hoen, B., & Piarroux, R. (2006). Negligible risk for epidemics after geophysical disasters. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12(4), 543–548.

- Fussell, E., & Lowe, S. R. (2014). The impact of housing displacement on the mental health of low-income parents after Hurricane Katrina. Social Science & Medicine, 113, 137–144.

- Galea, S., Brewin, C. R., Gruber, M., Jones, R. T., King, D. W., King, L. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(12), 1427–1434.

- Guha-Sapir, D., & van Panhuis, W. (2005). The Andaman Nicobar earthquake and tsunami 2004: Impact on diseases in Indonesia. Brussels: Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters.

- Halpern, J., & Tramontin, M. (2007). Disaster mental health: Theory and practice. Belmont, CA: Thomson.

- Hull, D., Grindlinger, G., Hirsch, E., Petrone, S., & Burke, J. (1985). The clinical consequences of an industrial aerosol plant explosion. Journal of Trauma, 25(4), 303–308.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. (2007). Disaster data. In World Disasters Report 2007 (pp. 172–181). Geneva: Author. Retrieved from http://www.ifrc.org/en/publications-and-reports/world-disasters-report/wdr2007

- Keim, M. (2002). Intentional chemical disasters. In D. E. Hogan & J. L. Burstein (Eds.), Disaster medicine (pp. 340–348). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Keim, M. (2006). Disaster preparedness. In G. R. Ciottone (Ed.), Disaster medicine (pp. 164–173). Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier.

- Keim, M. (2008). Building human resilience: The role of public health preparedness and response as an adaptation to climate change. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), 508–516.

- Keim, M., Humphrey, A., & Dreyfus, A. (2000). Situation assessment report involving the hazardous material disaster site at La Guaira Port, Venezuela. In CDC Report to Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance, US Agency for International Development.

- Kessler, R. C., Galea, S., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Ursano, R. J., & Wessely, S. (2008). Trends in mental illness and suicidality after Hurricane Katrina. Molecular Psychiatry, 13(4), 374–384.

- Kim, S. (2006). Flood. In G. R. Ciottone (Ed.), Disaster medicine (pp. 489–491). Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier.

- King, R. V., Burkle, F. M., Jr., Walsh, L. E., & North, C. S. (2015). Competencies for disaster mental health. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(3), 548.

- Klinenberg, E. (2002). Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Leong, K. J., Airriess, C. A., Li, W., Chen, A. C., & Keith, V. M. (2007). Resilient history and the rebuilding of a community: The Vietnamese American community in New Orleans East. Journal of American History, 94, 770–779.

- Lillibridge, S. (1997). Industrial disasters. In E. K. Noji (Ed.), The public health consequences of disasters (pp. 354–372). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Malilay, J. (1997). Floods. In E. K. Noji (Ed.), The public health consequences of disasters (pp. 287–300). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Mehta, P. S., Mehta, A. S., Mehta, S. J., & Makhijani, A. B. (1990). Bhopal tragedy's health effects. JAMA, 264(21), 2781–2787.

- Neria, Y., Galea, S., & Norris, F. H. (2009). Mental health and disasters. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nozaki, E., Nakamura, A., Abe, A., Kagaya, Y., Kohzu, K., Sato, K., & Mochizuki, I. (2013). Occurrence of cardiovascular events after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami disaster. International Heart Journal, 54(5), 247–253.

- Reifels, L., Pietrantoni, L., Prati, G., Kim, Y., Kilpatrick, D. G., Dyb, G.,…O'Donnell, M. (2013). Lessons learned about psychosocial responses to disaster and mass trauma: An international perspective. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(10), 3402.

- Sanderson, L. (1992). Toxicologic disasters: Natural and technologic. In J. Sullivan & G. Krieger (Eds.), Hazardous materials toxicology: Clinical principles of environmental health (pp. 326–331). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

- Sanderson, L. (1997). Fires. In E. K. Noji (Ed.), The public health consequences of disasters (pp. 373–396). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Sattler, D. N., Preston, A. J., Kaiser, C. F., Olivera, V. E., Valdez, J., & Schlueter, S. (2002). Hurricane Georges: A cross-national study examining preparedness, resource loss, and psychological distress in the U.S. Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic, and the United States. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15, 339–350.

- Silove, D., & Steel, Z. (2006). Understanding community psychosocial needs after disasters: Implications for mental health services. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine, 52(2), 121–125.

- Thomas, D.S.K., Phillips, B. D., Lovekamp, W. E., Fothergill, A., & Toole, M. J. (Eds.). (2013). Social vulnerability to disasters (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Toole, M. J. (1997). Communicable disease and disease control. In E. K. Noji (Ed.), The public health consequences of disasters (pp. 79–100). New York: Oxford University Press.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2009). Human development report 2009. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2009

- United Nations Development Programme. (2014). Human development report 2014. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr14-report-en-1.pdf

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2007). Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the resilience of nations and communities to disasters. Geneva: Author. Retrieved from http://www.unisdr.org/files/1037_hyogoframeworkforactionenglish.pdf

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. (2009). Terminology on disaster risk reduction. Retrieved from http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/terminology

- U.K. Department for International Development. (2011). Defining disaster resilience: A DFID approach paper. London: Author. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/186874/defining-disaster-resilience-approach-paper.pdf

- Ursano, R. J., Fullerton, C. S., Weisaeth, L., & Raphael, B. (2011). Textbook of disaster psychiatry. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Venezuela seeks contractors for hazardous cleanup. (2000). Hazardous Substances Spill Report, 3(2).

- Walker, B., & Salt, D. (2006). Resilience thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Weiss, W., Kirsch, T., Doocy, S., & Perrin, P. (2014). A comparison of the medium-term impact and recovery of the Pakistan floods and the Haiti earthquake: Objective and subjective measures. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 29(3), 237–244.

- World Bank. (2010). Natural hazards, unnatural disasters. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.gfdrr.org/sites/gfdrr.org/files/nhud/files/NHUD-Report_Full.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2009) Vegetation fires (Fact sheet). Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/ems/vegetation_fires/en

- Zhang, L., Zhao, M., Fu, W., Gao, X., Shen, J., Zhang, Z.,…Chen, X. (2014). Epidemiological analysis of trauma patients following the Lushan earthquake. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e97416.

For Further Information

Frameworks and Programs

- Grand Challenges for Disaster Reduction: http://sdr.gov/SDRGrandChallengesforDisasterReduction.pdf. The Subcommittee on Disaster Reduction, an element of the President's National Science and Technology Council, has developed a ten-year strategy called Grand Challenges for Disaster Reduction. It describes six grand challenges for disaster reduction and provides a framework for prioritizing the federal investments in science and technology.

- Hyogo Framework for Action 2005–2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters: http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/1037. The Hyogo Framework for Action (HFA) is the key instrument for implementing disaster reduction that has been adopted by the member states of the United Nations. Its overarching goal is to build the resilience of nations and communities to disasters by achieving substantial reductions of disaster losses by 2015.

- International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (ISDR): http://www.unisdr.org/eng/about_isdr/isdr-mission-objectives-eng.htm. The ISDR, which is implemented by the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR), aims at building disaster resilient communities by promoting increased awareness of the importance of disaster reduction as an integral component of sustainable development, with the goal of reducing human, social, economic, and environmental losses due to natural hazards and related technological and environmental disasters.

- National Incident Management System of the Federal Emergency Management Agency: http://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nims/NIMS_core.pdf. The National Incident Management System (NIMS) provides a systematic, proactive approach to guide departments and agencies at all levels of government, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector to work seamlessly together before, during, and after emergencies.

- National Response Framework of the Federal Emergency Management Agency: http://www.fema.gov/pdf/emergency/nrf/nrf-core.pdf. The national response framework is a guide for conducting all responses to hazards in the United States. It is built on a scalable, flexible, and adaptable coordinating structure that aligns key roles and responsibilities across the nation, linking all levels of government, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector.

- National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (National VOAD): http://www.nvoad.org. National VOAD is a forum where organizations can share knowledge and resources throughout the disaster cycle—preparation, response, and recovery—to help disaster survivors and their communities. Members of National VOAD come together as a coalition of nonprofit organizations that respond to disasters as part of their overall missions.

- Preparedness and Emergency Response Learning Centers (PERLCs): http://www.cdc.gov/phpr/perlc.htm. A program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that provides funding for fourteen PERLCs across the United States. PERLCs provide training to state, local, and tribal public health authorities in the area of public health preparedness and response.

- Reducing Disaster Risk: A Challenge for Development: http://www.undp.org/cpr/disred/documents/publications/rdr/english/rdr_english.pdf. The aim of this report from the United Nations Development Programme is to map out an agenda for change in the way disaster risk is perceived within the development community. It presents a range of opportunities for moving development pathways toward meeting the UN Millennium Development Goals by integrating disaster risk reduction into development planning.

- Yokohama Strategy and Plan of Action for a Safer World: Guidelines for Natural Disaster Prevention, Preparedness and Mitigation: http://www.unisdr.org/we/inform/publications/8241. This document provides guidelines for natural disaster prevention, preparedness, and mitigation. It is divided into three sections: Part I describes the principles on which a disaster reduction strategy should be based, Part II is a plan of action agreed upon by all member states of the United Nations, and Part III gives some guidelines concerning the follow-up of action.

Guides and Handbooks

Two general and comprehensive guides to disaster response are the following:

- Ciottone, G. R. (Ed.). (2006). Disaster medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier. This book is designed to serve as both a comprehensive text and a quick resource. Part 1 introduces the many topics of disaster medicine and management, with an emphasis on the multiple disciplines. Part 2 introduces the reader to every conceivable disaster scenario and the management issues surrounding each of them.

- Landesman, L. (2005). Public health management of disasters: The practice guide. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. Among the useful features of Dr. Landesman's guide is a recognition of the public health component of disasters—a neglected area. Frequently, emergency response focuses on environmental degradation or terrorism concerns but not on the basic health concerns of each disaster, which are at least as likely to pose challenges. In support of this idea, the author delineates various types of disasters and the public health implications of each.

Following is a listing of guidebooks commonly used during responses to environmental disasters.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). Public health emergency response guide for state, local, and tribal public health directors (Version 2.0). Available at http://www.bt.cdc.gov/planning/responseguide.asp

- The Sphere Project. (2004). Humanitarian charter and minimum standards in disaster response. Available at www.sphereproject.org

- UNICEF. (2005). Emergency field handbook: A guide for UNICEF staff. New York: Author.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. (2000). Handbook for emergencies (2nd ed.). Geneva: Author.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Agency for International Development. (n.d.). Field operations guide for disaster assessment and response. Available for purchase at https://bookstore.gpo.gov/products/sku/001-300-00003-2?ctid=688

- World Health Organization. (2003). Emergency response manual: Guidelines for WHO representatives in country offices in the Western Pacific region. Manila: Author.

- World Health Organization. (2013). A systematic review of public health emergency operations centres (EOC) (WHO/HSE/GCR/2014.1). Geneva: Author. Available at www.who.int/ihr/publications/WHO_HSE_GCR_2014.1/en

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Africa. (2014). Standard operating procedures for coordinating public health event preparedness and response in the WHO African Region. Brazzaville: Author. Available at www.who.int/hac/techguidance/tools/standard_operating_procedures_african_region_en_2014.pdf?ua=1

- World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization. (2003). WHO-PAHO guidelines for the use of foreign field hospitals in the aftermath of sudden-impact disasters. San Salvador: PAHO, 2003.