Chapter 25

Nature Contact

Howard Frumkin

Dr. Frumkin's disclosures appear in the front of this book, in the section titled “Potential Conflicts of Interest in Environmental Health: From Global to Local.”

Much of this book is about hazards. We learn that contaminated water can cause diarrheal diseases (Chapter 16), that air pollution can cause respiratory disease (Chapter 13), that poorly designed roadways can result in injuries (Chapters 15 and 23), that degraded urban environments may encourage violence (Chapter 9). Clearly, environmental exposures can threaten health—and this is a central focus of the environmental health field.

But the environment, and in particular the natural world, may also enhance health. One example, the concept of ecosystem services, is explored in Chapter 2 (Kareiva, Tallis, Ricketts, Daily, & Polasky, 2011); many pharmaceuticals derive from plants (a compelling argument for preserving biodiversity). Another example is even more intuitive: contact with the natural world may directly benefit health. That idea is the starting point for this chapter.

The Links Between Nature and Human Health

Many people appreciate a walk in the park, the sound of a bird's song, or the sight of ocean waves lapping at the seashore. In the words of University of Michigan psychologist Rachel Kaplan (1983, p. 155): “Nature matters to people. Big trees and small trees, glistening water, chirping birds, budding bushes, colorful flowers—these are important ingredients in a good life.” Cross-cultural studies suggest that these preferences are so widely held as to be nearly universal. In recent years researchers have asked whether these are more than simply aesthetic preferences. If people find tranquility in certain natural environments—a sense of comfort, restoration, even healing—then contact with nature might be an important component of health and well-being.

From an evolutionary perspective, a deep-seated connection with the natural world would be no surprise. Primate evolution began at least 65 million years ago, and the first hominids appeared as much as 5 million years ago. Two million years ago australopithecines were fashioning primitive stone tools and hunting in bands on the grassy savannas of Africa. Homo habilis probably appeared 2 or 3 million years ago, and our immediate predecessor, Homo erectus, appeared about 1.5 million years ago. Human history as we now know it began during the Neolithic period, just 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, when the last great ice age ended and climate and ecology came to resemble those of our current world. Our ancestors—true Homo sapiens—began to form settlements, cultivate crops, domesticate animals, dig mines, and even make art. If the last 2 million years of our species' history were scaled to a single human lifetime of seventy years, then the first humans would not have begun settling into villages until eight months after their 69th birthday. Some people—indigenous groups in Australia, South America, the Pacific Islands, and elsewhere—would remain hunter-gatherers until a day or two before turning 70. We have broken with long-established patterns of living rather late in our life as a species.

For the great majority of human existence, human lives have been embedded in the natural environment. Those who could navigate it well—who could smell the water, find the plants, follow the animals, recognize the safe haven—must have enjoyed survival advantages. According to biologist E. O. Wilson (1993, p. 32), “It would…be quite extraordinary to find that all learning rules related to that world have been erased in a few thousand years, even in the tiny minority of peoples who have existed for more than one or two generations in wholly urban environments.” Wilson hypothesized the existence of biophilia, “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms” (Wilson, 1984, p. 31). Building on this theory, others have postulated an affinity for nature that goes beyond living things to include streams, ocean waves, and wind (Heerwagen & Orians, 1993).

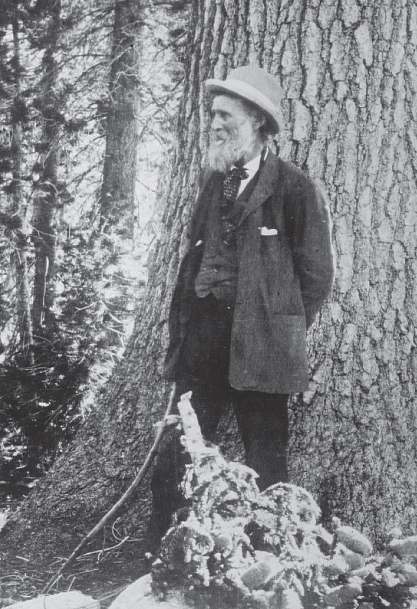

The human connection to nature and the idea that this connection might be a component of good health have a long history in philosophy, art, and popular culture (see, e.g., Nash, 1982; McLuhan, 1994). The New England transcendentalists, almost two centuries ago, argued that the human spirit was rooted in nature, and a leading exponent, Henry David Thoreau, wrote of the “tonic of wildness.” A century later the conservationist John Muir (Figure 25.1) observed, “Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life” (Fox, 1981, p. 116).

Figure 25.1 John Muir ({–1914) Was a Naturalist and Conservationist Whose Writings Had a Profound Influence on American Attitudes Toward Nature

Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs, n.d.

But the history of human culture has also in many ways been the history of separation from nature. David Abram (1996) argues that this separation began with the very development of language, which replaced nature images with abstract symbols as central elements of human cognition and communication. Although our ancestors lived in close proximity to nature, their struggle to survive was in many ways a struggle to vanquish nature, or at least to shape it to their ends and to control its most drastic exigencies. The book of Genesis, which dates from about 3,000 years ago, included the often-repeated divine mandate, “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” (Contemporary environmental thinkers have imputed a gentler meaning to this passage, emphasizing stewardship rather than conquest.) The ancient Greeks abstracted human learning from nature. In the Platonic dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates finds himself outside the city walls, and grumbles to his companion, “I'm a lover of learning, and trees and open country won't teach me anything, whereas men in town do” (Hamilton & Cairns, 1961, p. 479). For Socrates, wisdom and comfort were to be found in human society, apart from, and above, the world of nature. Subsequent developments have led most people, at least in wealthy nations, to live lives that are effectively insulated from the natural world. In the words of environmental historian Roderick Nash (1982, p. 267), “For thousands of years after our race opted for a civilized existence, we dreamed of and labored toward an escape from the anxieties of a wilderness condition only to find, when we reached the promised land of supermarkets and air conditioners, that we had forfeited something of great value.”

Through what mechanisms might nature contact benefit health? Some of the answer may lie in psychological explanations. In addition, nature contact may facilitate healthy behaviors such as physical activity and socializing. Finally, the natural environment provides services, such as improving air quality, that promote health.

Environmental Psychology and Nature Contact

Environmental psychology offers three perspectives that shed light on the benefits of nature contact: attention restoration, stress reduction, and child development.

Attention Restoration

Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) emphasized the importance of directed attention, the ability to focus and block competing stimuli during purposeful activity. They proposed that people can develop attentional fatigue from excessive concentration, resulting in memory loss, diminished ability to focus, and greater impatience and frustration in interpersonal interactions. Moreover, they suggested that contact with nature could be restorative—renewing attention and improving cognitive abilities. This construct is called attention restoration (S. Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan & Berman, 2010). Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) noted four aspects of restorative environments: fascination (effortless interest or curiosity); a sense of being away from one's usual setting, extent, or scope (being part of a larger whole); and compatibility with one's preferences.

Research has supported the link between nature contact and attention restoration. For example, one study (Tennessen & Cimprich, 1995) showed that college students with more natural views from their dormitory windows had higher levels of attention and cognitive function than those without. A study of apartment dwellers (S. Kaplan, 2001) showed that those with window views of landscaped lawns and gardens, trees, farms, and fields scored higher on measures of effective functioning (including “focused,” “ effective,” and “attentive”) and lower on measures of distraction (including “forgetful,” “disorganized,” and “difficult to finish things you have started”) than those without such views. Other research shows that people with illnesses that may impair their attention or cognitive performance, from breast cancer to depression, benefit from contact with nature in this way. Such results have been demonstrated in children as well. For example, children who had moved from substandard housing to “greener” homes (with more views of nearby nature) were found to have higher levels of cognitive functioning after the move than before (Wells, 2000), girls in a low-income housing project were found to have greater self-discipline if they had nature views from home than did girls in the same project who lacked such views (Faber Taylor, Kuo, & Sullivan, 2002), and children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder were rated by their parents as having reduced symptoms after playing in relatively natural settings, compared to their behavior after playing in built outdoor and indoor settings (Kuo & Taylor, 2004). Nature contact may be beneficial, at least in part, through attention restoration.

Stress Reduction

Nature contact may also function through stress reduction. This is an intuitive notion; many people choose vacations in beautiful natural locations, probably expecting their stress to diminish. Again, research supports this notion. For example, Ulrich et al. (1991) exposed undergraduate students to a stressful film, followed by a variety of videotapes of natural and urban settings. The students' stress recovery, as measured by self-report and cardiovascular measurements, was significantly faster when they viewed the nature scenes. In recent studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging, people who were brought up in cities and/or currently lived in cities showed enhanced brain activity in regions related to stress response, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, compared to rural counterparts (Lederbogen et al., 2011). Among both children (Wells & Evans, 2003) and adults (van den Berg, Maas, Verheij, & Groenewegen, 2010a), individuals who live in greener areas react to stressful life events with significantly less psychological distress than those in less green areas. Green schoolyards function as “havens from stress” for children (Chawla, Keena, Pevec, & Stanley, 2014). Results such as these suggest that nature contact may function, at least acutely, to mitigate stress. In turn, stress reduction, perhaps together with attention restoration and/or direct antidepressant effects (Berman et al., 2012; Cohen-Cline, Turkheimer, & Duncan, 2015), may yield cognitive and emotional benefits (Bratman, Hamilton, & Daily, 2012).

Child Development

Nature contact might be healthy in a third way: by playing a role in wholesome child development. Psychologists and others (Nabhan & Trimble, 1994; Kahn & Kellert, 2002; Louv, 2005) have argued that children's ability to develop perceptual and expressive skills, imagination, moral judgments, and other attributes is greatly enhanced by contact with nature. For example, studies of Barcelona schoolchildren found that playtime in green settings, living near green space, and visiting “bluespace” (lakes and beaches) were associated with fewer emotional symptoms, fewer conduct problems, less hyperactivity/inattention, and fewer peer relationship problems (Amoly et al., 2014), and that green space near schools was associated with improved cognitive development (Dadvand et al., 2015). Chapter 11 introduces the concept that children have windows of vulnerability to toxic exposures; children may also have developmental windows during which nature contact fills important needs (Text Box 25.1).

Nature as a Setting for Healthy Behaviors

Physical Activity

Physical activity is a powerful predictor of good health, so settings that encourage physical activity are likely to promote health. As described in Chapter 15, a range of environmental factors predict how active people are, both in the ways they travel (active transportation) and in their leisure time activities; these factors include pedestrian and bicycle infrastructure, proximity of destinations, perceived safety, and more. Green space is another such factor; it may encourage physical activity by providing attractive settings. Much research suggests that natural features such as street trees, nature views, and proximity to parks promote physical activity. However, not all studies support this association, perhaps because plentiful green space is sometimes associated with low-density communities, meaning that residents have longer distances to destinations and more automobile dependence (Hartig, Mitchell, de Vries, & Frumkin, 2014; Bancroft et al., 2015). Among children, being outside predicts higher levels of physical activity (e.g., Cleland et al., 2008; Schaefer et al., 2014); contact with nature may be an important part of this effect.

Social Connectedness

Parks and similar natural settings may encourage the development of social ties. This may be mediated through one of the mechanisms noted above; for example, being with other people in a low-stress setting may facilitate social bonding. Evidence suggests that parks promote social capital in neighborhoods (Kaźmierczak, 2013; Holtan, Dieterlen, & Sullivan, 2014; Kemperman & Timmermans, 2014) and that people who live in green neighborhoods feel less lonely than people who live in less green neighborhoods (Maas et al., 2009). A study in Zurich found that children who regularly played outside in natural areas had more than twice as many playmates as children restricted to indoor play because of heavy nearby traffic (Hüttenmoser, 1995)—a benefit that extended to their parents as well. Interestingly, the social connectedness provided by nature may not relate only to other people. There is a social quality to pet ownership, both in the relationship between pet owners and their pets (pets are called companion animals for a reason) and in the way that pet owners interact with other people through their pets (McConnell, Brown, Shoda, Stayton, & Martin, 2011; Stanley, Conwell, Bowen, & Van Orden, 2014). Some of the health benefits of pet ownership may relate to these social ties.

Ecosystem Services and Health

Air Quality

Trees, shrubs, and other vegetation may affect ambient air quality, which in turn affects human health and well-being. Interestingly, the effects are not all positive. Trees and other vegetation effectively reduce levels of some pollutants, including gases and particulate matter (Escobedo, Kroeger, & Wagner, 2011). However, these are generally not large effects (Nowak, Hirabayashi, Bodine, & Greenfield, 2014). Indoors, plants can be effective at removing contaminants from the air, especially if the right species are chosen (Yoo, Kwon, Son, & Kays, 2006). On the negative side, trees may contribute to air pollution by releasing hydrocarbons such as pinenes and terpenes, precursors of ozone and secondary organic aerosols (Sartelet, Couvidat, Seigneur, & Roustan, 2012). Some trees and plants release pollen, aggravating allergies (Cariñanos & Casares-Porcel, 2011). Finally, trees can improve air quality indirectly. During warm weather, trees help cool places down by offering shade and through the cooling effects of evapotranspiration. This in turn reduces both ozone formation and energy demand, which, in areas served by coal-fired power plants, reduces air pollution derived from coal combustion.

Other Services

Nature provides a range of other ecosystem services that benefit people. For example, in cities, trees help counteract the urban heat island effect and provide cooling during heat waves, provide stormwater management that helps prevent flooding, and provide noise reduction. In addition, nearby trees, parks, and open space increase residential property values, enabling communities to collect the tax revenues needed to maintain such amenities (Crompton, 2005).

These direct and indirect mechanisms suggest a range of ways in which nature may benefit health and well-being. Where and how does nature contact occur, and what are the implications for public health policy?

Domains of Nature Contact

Evidence that our contacts with nature can be beneficial to health is available from at least four aspects of the natural world—animals, plants, landscapes, and wilderness experiences.

Animals

Animals have played a prominent part in human life since prehistoric times (Clutton-Brock, 1981; Caras, 1996). According to the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (www.aza.org), over 175 million people visit zoos and aquariums in the United States each year—more than attend professional football, baseball, hockey, and basketball games combined. About two thirds of U.S. households have a pet: about 44% of households have one or more dogs and about 35% have one or more cats, corresponding to national populations of about 78 million dogs and 86 million cats (American Pet Products Association, 2015) (Figure 25.2). More than 90% of the characters used in preschool books to teach children language and counting are animals (Kellert, 1993, p. 52). Numerous studies have established that household animals are considered family members; people talk to their pets as if they were human, carry their photographs, buy them birthday presents, and share their bedrooms with them (Beck & Katcher, 1983; Fleishman-Hillard Research, 2007). Half of pet owners report that if faced with financial hardship, they would cut back on groceries, entertainment, and household goods before they would cut back on pet care (Fleishman-Hillard Research, 2007). Among pet owners, 50% of adults and 70% of adolescents confide in their pets (Beck & Meyers, 1996). During disasters, many pet owners refuse to evacuate without their pets (as was seen during Hurricane Katrina, for example), and those who lose their pets suffer considerable mental distress (Hunt, Al-Awadi, & Johnson, 2008).

Figure 25.2 The Human-Animal Bond

Source: Addicks, 2008. Photo © 2008 Trisha Addicks.

A wide body of evidence links animals with human health (Friedman & Son, 2009; Natterson-Horowitz & Bowers, 2013; Cherniack & Cherniack, 2014; Matchock, 2015). Some of the evidence relates to pet ownership, and some relates to the use of animals in therapy, for conditions as diverse as autism spectrum disorders, loneliness, dementia, and having been the victim of sexual abuse. Results generally suggest benefits, although many reviewers comment that the available research lacks sufficient rigor and leaves important questions unanswered. Human-animal interaction (HAI) seems to be health promoting for child development (Endenburg & van Lith, 2011), cardiovascular health (Levine et al., 2013), healthy aging (Cherniack & Cherniack, 2014), and in other ways. And human-animal interaction seems to improve outcomes in a variety of conditions, such as autism spectrum disorder (Muñoz Lasa, Ferriero, Brigatti, Valero, & Franchignoni, 2011; O'Haire, 2013), stress (Beetz, Uvnäs-Moberg, Julius, & Kotrschal, 2012), and even HIV infection (Saberi, Neilands, & Johnson, 2014).

Several examples are instructive. In a study in a Melbourne cardiovascular disease risk clinic, nearly 6,000 patients were divided into those who owned pets and those who did not. The pet owners had lower systolic blood pressure, cholesterol, and triglycerides than the non–pet owners, an effect that reached statistical significance among men but not women. These findings could not be explained by differences in exercise levels (say, from dog walking), in diet, in social class, or in other confounders (Anderson, Reid, & Jennings, 1992). In a study at clinical sites across the United States and Canada, 369 survivors of myocardial infarction were followed for one year. Of these, 112 owned pets and 257 did not. The dog owners had a one-year survival rate six times higher than that of the non–dog owners, and this benefit was not due to physiological differences. (Cat owners showed no such advantage, perhaps reflecting the adage “dogs have owners and cats have staff.”) (Friedmann & Thomas, 1995). In a study of 240 married couples, half with pets and half without, participants were exposed to two stressors (a mathematical task and immersing a hand in cold water) under one of four conditions: alone, with a companion (the pet for pet owners and a friend for non–pet owners), with the spouse, or with both companion and spouse. Pet owners had lower baseline heart rate and blood pressure, lower cardiovascular reactivity to the stressors, and faster recovery, and the advantage was most marked when the pet was present during the testing (Allen, Blascovich, Wendy, & Mendes, 2002).

Investigators in Cambridge, England, followed seventy-one adults who had just acquired pets and compared them with twenty-six petless controls over a ten-month period. Within a month of acquiring the pet the pet owners showed a statistically significant decrease in minor health problems. In the dog owners (but not the cat owners) this improvement was sustained for the entire ten months of observation (Serpell, 1991). In another study, this one in the United States, 938 Medicare enrollees were divided into pet owners and non–pet owners. The pet owners, especially the dog owners, had fewer physician visits than non–pet owners. Moreover, stressful life events triggered more doctor visits among those without pets but not among pet owners, suggesting that owning a pet helped mediate stress (Siegel, 1990). (Some of the results in these examples were not replicated by other studies, emphasizing that there is more to learn about these effects [McNicholas et al., 2005].)

Animal-assisted therapy has been utilized in treating a range of conditions, including pervasive developmental disorders, cardiovascular disease, psychiatric disorders, chronic pain, Alzheimer's disease, and cancer (Muñoz Lasa et al., 2011; D. A. Marcus, 2013). For example, in a Virginia psychiatric hospital, 230 patients with mood disorders, schizophrenia, substance abuse disorders, and other diagnoses were treated with both a session of animal-assisted therapy (featuring interaction with a dog) and a session of conventional recreational therapy, using a crossover design. Both therapies reduced the patients' anxiety levels as measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, but in all diagnostic groups except the group with mood disorders, the animal-assisted therapy achieved substantially greater reductions (Barker & Dawson, 1998).

The mechanisms of benefit from animal contact are unclear. They may relate to the link to nature (through stress reduction and/or attention restoration), to companionship (with other pet owners or with the animals themselves), or to other factors (Beck & Katcher, 1983; Wood, Giles-Corti, & Bulsara, 2005; Wood, Giles-Corti, Bulsara, & Bosch, 2007). The relationship with a pet may even involve mirror neuron activity (Toohey, McCormack, Doyle-Baker, Adams, & Rock, 2013). Whatever the mechanism, the bulk of the evidence supports the conclusion of animal researchers Alan Beck and N. Marshall Meyers (1996, p. 249): “Preserving the bond between people and their animals, like encouraging good nutrition and exercise, appears to be in the best interests of those concerned with public health.”

Plants

People feel good around plants. Survey research (and subjective experience) confirms that people like access to plants at home, at work, at school, in their gardens, and in their neighborhoods (Lohr, 2010). Access to plants has been credited with a range of benefits, such as stress reduction, improved performance, and feelings of contentment and happiness. Four kinds of encounters with plants are instructive: while indoors, gardening, in neighborhoods, and in therapeutic settings.

Indoor exposure to plants may occur at work, at home, and in classrooms. At work employees report that plants make them feel calmer and more relaxed, and that an office with plants is a more desirable place to work (although work performance does not necessarily improve) (Larsen, Adams, Deal, Kweon, & Tyler, 1998; Pearson-Mims & Lohr, 2000). Research in schools yields similar findings. In a study of a junior high school (Han, 2009), students with plants in their classrooms reported stronger feelings of preference, comfort, and friendliness; had less sick leave; and had less misbehavior than students in a control classroom, and in a study of university students (Doxey, Waliczek, & Zajicek, 2009), those with plants in their classrooms rated their learning and their instructor's performance significantly higher than did students in control classrooms. In neither case did academic performance improve with the presence of plants.

Gardening, which involves intimate contact with plants, also seems to offer benefits. For example, in the Dubbo Study, a longitudinal cohort study of 2,805 elderly people in New South Wales, 56% of men and 41% of women gardened daily. Compared with those not gardening, daily gardeners enjoyed a 40% lower risk of admission for dementia, and those gardening weekly or less often had an 11% reduction (Simons, Simons, McCallum, & Friedlander, 2006). While some of the benefit likely comes from physical activity (Nicklett, Anderson, & Yen, 2014) and the social aspects of gardening, additional benefit may come directly from contact with plants. Community gardening has been studied as a public health strategy, as explored in Text Box 25.2.

At the neighborhood scale, contact with plants comes from nearby parks and green spaces and from tree canopies over streets—features comprising what are sometimes called green neighborhoods. Trees hold a special place in many people's hearts. Psychologist Michael Perlman (1994) has written of the psychological power of trees, as evidenced by mythology, dreams, and self-reported emotional responses, and the poet Joyce Kilmer, in 1913, famously (and humbly) wrote, “I think that I shall never see / A poem lovely as a tree.” Green neighborhoods, generally measured by the extent of tree canopy, have been associated with positive health outcomes across the lifespan: improved birth outcomes (Dadvand et al., 2012), lower body mass index and slower weight gain in children (Bell, Wilson, & Liu, 2008), improved social ties (Holtan et al., 2014), more resilience to stressful life events (van den Berg et al., 2010a), better self-reported health (Carter & Horwitz, 2014), and longer life expectancy among elders (Takano, Nakamura, & Watanabe, 2002). In a study in Toronto (Kardan et al., 2015), investigators found that after controlling for relevant risk factors, greener neighborhoods were associated with better self-reported health and lower rates of cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes. In that study an increment of ten trees per city block improved self-reported health to the same extent as a $10,000 increase in income or being seven years younger!

The long-standing view that plant contact is good for health has led to therapeutic approaches such as healing gardens and horticultural therapy. The great neurologist Oliver Sacks highlighted this approach in a memorable passage in his 1984 account of recovery from a serious leg injury, A Leg to Stand On. After more than two weeks in a small hospital room with no outside view, and a third week on a dreary surgical ward, he was finally taken out to the hospital garden:

This was a great joy—to be out in the air—for I had not been outside in almost a month. A pure and intense joy, a blessing, to feel the sun on my face and the wind in my hair, to hear birds, to see, touch, and fondle the living plants. Some essential connection and communion with nature was re-established after the horrible isolation and alienation I had known. Some part of me came alive, when I was taken to the garden, which had been starved, and died, perhaps without my knowing it [pp. 133–134].

Sacks credited his garden contact with an important role in his recovery and mused that perhaps more hospitals should have gardens or even be set in the countryside or near woods. In fact, gardens have been a feature of hospitals and other health care settings since ancient times, and interest has resurged in recent years (C. C. Marcus, 2007; Marcus & Sachs, 2013).

The therapeutic potential of plants is also harnessed in a treatment approach called horticultural therapy (Simson & Straus, 2003; Haller & Kramer, 2006). Horticultural therapy is used not only in hospitals but also in community-based programs, geriatrics programs, prisons, developmental disabilities programs, and special education (Mattson, 1992). In prisons, one observer noted that gardening has a “strangely soothing effect,” making “pacifists of potential battlers” (Neese, 1959) and seemingly decreasing the numbers of assaults among prisoners (Hunter, 1970, reported in Lewis, 1990). Horticultural therapy has been used to treat dementia, severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression, and in cardiac and stroke rehabilitation. Although rigorous evidence is scarce, some studies support the efficacy of horticultural therapy (Annerstedt & Währborg, 2011; Kamioka et al., 2014). For example, researchers at New York's Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation Medicine compared horticultural therapy with routine patient education in cardiac rehabilitation patients. Horticultural therapy significantly reduced both the heart rate and the total mood disturbance as measured by the Profile of Mood States (POMS) inventory, whereas patient education classes did not (Wichrowski, Whiteson, Haas, Mola, & Rey, 2005). Such evidence offers support for the hypothesis that proximity to plants, like proximity to animals, may in some circumstances enhance health.

Landscapes

Natural landscapes may also offer health benefits. Returning to an evolutionary perspective, human history probably began on the African savanna, a region of open grasslands punctuated by scattered copses of trees and denser woods near rivers and lakes. If this sounds like the choicest real estate in most cities and towns, that may not be a coincidence. As E. O. Wilson (1984, pp. 109–110) wrote, “certain key features of the ancient physical habitat match the choices made by modern human beings when they have a say in the matter”—a pattern that repeats in parks, cemeteries, golf courses, and lawns. “It seems that whenever people are given a free choice,” Wilson observed, “they move to open tree-studded land on prominences overlooking water.”

Could evolution have selected for certain landscape preferences? Perhaps. A crucial step in the lives of most organisms, including humans, is selection of a habitat. If a creature gets into the right place, everything is likely to be easier. “Habitat selection depends on the recognition of objects, sounds, and odors to which the organism responds as if it understood their significance for future behavior and success” (Heerwagen & Orians, 1993, p. 140). For example, many birds use patterns of tree density and vertical arrangement of branches as primary settling cues; presumably these cues correlate with crucial information about such benefits as food availability and concealment from predators. For early humans a place with an open view would have offered opportunities to spot food and shelter and to avoid predators. But not too open a view: clumps of trees would offer hiding places in a pinch and, like streams and lakes, might also signal the presence of prey for the hunter (Ulrich, 1993). Going further, perhaps the ability to identify relaxing, restorative settings, which could also improve the capacity to recover from fatigue and stress, could also have been adaptive (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Ulrich, 1993). If you can run away from a saber-toothed tiger, your survival is enhanced. But if, having run away, you can then get to a peaceful place, relax, and gather your strength, that may further enhance your survival. Perhaps individuals who chose such settings gained a survival advantage (Ulrich, 1993).

There is considerable evidence that people's aesthetic preferences conform to this prediction (Ward Thompson, 2011). As suggested above, when offered a variety of landscapes, people react most positively to savanna-like settings, with moderate to high depth or openness, relatively smooth or uniform-length grassy vegetation or ground surfaces, scattered trees or small groupings of trees, and water (Schroeder & Green, 1985; Kaplan, Kaplan, & Ryan, 1998). Notably, these findings emerge cross-culturally, in studies of North Americans, Europeans, Asians, and Africans (see, e.g., Hull & Revell, 1989; Purcell, Lamb, Mainardi Peron, & Falchero, 1994; Korpela & Hartig, 1996).

There is a great deal of research on people's reactions to landscapes. People viewing savanna–like settings report feelings of peacefulness, tranquility, or relaxation (Ulrich, 1993), decreased fear and anger, and enhanced positive affect (Honeyman, 1992). Moreover, viewing nature scenes is associated with enhanced mental alertness, attention, and cognitive performance, as measured by tasks such as proofreading and by formal psychological testing (Tennessen & Cimprich, 1995; Cimprich & Ronis, 2003). (Also see Text Box 25.3.)

These reactions seem to transfer to health outcomes as well. For example, consider four different vantage points for viewing landscapes: from a workplace, a prison, or a hospital room or during a medical procedure.

- In a workplace study, 615 office workers were surveyed regarding their work satisfaction, levels of frustration, enthusiasm for work, patience, and life satisfaction. Each of these outcomes was significantly better among those with views of nature through their windows (Kaplan, 1993).

- In 1981, Ernest Moore, a University of Michigan architect, took advantage of a natural experiment at the State Prison of Southern Michigan, a massive depression-era structure. Half the prisoners occupied cells along the outside wall, with a window view of rolling farmland and trees, and the other half occupied cells that faced the prison courtyard. Assignment to one or the other kind of cell was random. Compared to the prisoners in the exterior cells, the prisoners in the inside cells had a 24% higher frequency of sick call visits. Moore could not identify any design feature to explain this difference and concluded that the outside view “may provide some stress reduction” (Moore, 1981–1982).

- A short 1984 article in Science bore the provocative title “View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery.” Like the Michigan prison study, this study also took advantage of an inadvertent architectural experiment. On the surgical floors of a 200-bed, suburban Pennsylvania hospital, some rooms faced a stand of deciduous trees and others faced a brown brick wall. Postoperative patients were assigned essentially randomly to one or the other kind of room. The investigator reviewed the records of all cholecystectomy patients over a ten-year interval, restricted to the summer months when the trees were in foliage. Compared to patients with brick wall views, patients with tree views had significantly shorter hospitalizations (7.96 days compared to 8.70 days), less need for pain medications, and fewer negative comments in the nurses' notes (Ulrich, 1984).

- In a randomized clinical trial of patients undergoing bronchoscopy (insertion of a flexible fiber-optic tube through the trachea into the lungs), patients who viewed a nature scene (a mountain stream in a spring meadow) and heard recorded nature sounds (water in a stream or chirping birds) experienced better pain control than did patients who received only conventional sedation (although anxiety levels did not differ between the two groups) (Diette, Lechtzin, Haponik, Devrots, & Rubin, 2003).

Viewing landscapes and related nature scenes, whether in actuality or in pictures, seems to have a salutary effect. Certain landscape types, such as broadleaf woodland, improved grassland, and seascapes, may have especially positive effects (Wheeler et al., 2015) (Text Box 25.4).

Wilderness Experiences

Wilderness experiences—entering the landscape rather than only viewing it—may also be therapeutic. John Muir (1901, p. 56) wrote lyrically of his emotional and physical response to being in the wilderness: “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature's peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves.” David Cumes (1998a, 1998b) described a phenomenon he called wilderness rapture, involving self-awareness; feelings of awe, wonder, and humility; a sense of comfort in and connection to nature; increased appreciation of others; and a feeling of renewal and vigor. Others have described the spiritual inspiration that comes from wilderness experiences (Fredrickson & Anderson, 1999). Green exercise (Text Box 25.5) may represent a less intense version of this same phenomenon.

Clinicians have worked to transfer these benefits to therapeutic interventions, using wilderness therapy (also called adventure therapy) for emotionally disturbed or delinquent children and adolescents, bereaved people, rape and incest survivors, and patients with cancer, psychiatric illness, end-stage renal disease, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and addiction disorders, among other ailments (Russell, 2001). The literature on wilderness therapy includes both before-and-after comparisons and controlled studies; mental health end points are the most commonly studied. In one such study, a group of 5.5- to 11.5-year-olds, emotionally disturbed boys attending an outdoor day camp, was compared to a group of similar boys not attending the camp. The campers' self-ratings of their emotional adjustment and also their teachers' ratings were significantly better than those of the controls, although neither parents' ratings nor scores on formal psychological testing showed an improvement (Shniderman, 1974). In a convenience sample of more than 700 people who had participated in wilderness excursions lasting two to four weeks, 90% described “an increased sense of aliveness, well-being, and energy,” and 90% reported that the experience had helped them break an addiction (defined broadly and ranging from nicotine to chocolate) (Greenway, 1995). In a group of Australian wilderness adventure camps serving adults with mental illness, participants reported improved self-esteem, mastery, and social connectedness at the end of the camp, but had returned to baseline by four weeks later (Cotton & Butselaar, 2013).

The literature on wilderness adventures is extensive, but several features make it difficult to interpret (Wilson & Lipsey, 2000; Russell & Phillips-Miller, 2002; Ray & Jakubec, 2014). Much of the published research comes from “true believers” or proponents, such as adventure companies, with a personal or commercial interest in wilderness experiences. Much of the research refers to structured trips or summer camp programs rather than to the more general phenomenon of contact with wilderness. Beneficial outcomes may be due to the vacation quality of the experience, to the psychological value of setting and achieving difficult goals, or to the group bonding that occurs on some such trips (or to some combination of these), rather than (or in addition to) the wilderness contact itself. Few studies have been randomized, and selection bias can rarely be excluded. Blinding of subjects is impossible, and blinding of investigators has not been attempted. Despite these limitations, many published accounts do suggest some benefit from wilderness experiences, especially short-term benefit for behavioral health problems.

Risks of Nature Contact

While nature contact offers a range of health benefits, it also entails some risks. As with other public health interventions, optimizing the benefits means recognizing and controlling risks.

Chief among the risks of animal contact are bites and scratches, allergic reactions, and zoonotic diseases. With regard to allergy, the role of pets is complex. Exposure to animals early in life may protect against later allergy, while for people who are already sensitized, exposure may trigger symptoms (Dharmage, Lodge, Matheson, Campbell, & Lowe, 2012; Lodge et al., 2012; Smallwood & Ownby, 2012). Zoonotic diseases, from the unusual (e.g., psittacosis, brucellosis, leishmaniasis, echinococcosis, and dermatophytosis) to the common (e.g., infections with giardia, salmonella, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), may spread from companion animals to humans. While dogs and cats may transmit some of these diseases, exotic pets such as snakes, turtles, and birds pose some unique risks (Boseret, Losson, Mainil, Thiry, & Saegerman, 2013). As backyard chickens become more popular, public health officials have had to warn the public not to nuzzle the chickens, to reduce the risk of infection with salmonella or Newcastle or Marek's disease. Most at risk of zoonotic infections are young children, the elderly, pregnant women, and immunocompromised hosts (Mani & Maguire, 2009; Elad, 2013; Stull & Stevenson, 2015). For each of these hazards, preventive strategies, such as home hygiene, are available (Morris, 2010).

Contact with plants and engaging in outdoor activities also pose risks. These include allergic reactions to plants such as poison ivy, exposure to weather extremes, encounters with animals ranging from mosquitoes to snakes to large predators, and injuries such as falls and drowning. A full discussion of these risks, and how to control them, is beyond the scope of this chapter, but is available elsewhere (Auerbach, 2012). Public health principles very much apply: prevention, preparedness, and training are key to reducing risk.

There is evidence, then, that contact with the natural world—with animals, plants, landscapes, and wilderness—may offer health benefits. Perhaps this reflects ancient learning habits, preferences, and tastes, echoes of human origins as creatures of the wild. Satisfying these preferences by promoting contact with the natural world may be an effective way to enhance health (not to mention cheaper and freer of side effects than medications). If so, this implies a broad vision of environmental health, one that stretches from landscape architecture to horticulture, from interior design to forestry, from botany to veterinary medicine.

The Greening of Environmental Health

With accumulating evidence that nature contact provides health benefits, the public health response might take three forms: research, collaboration, and public health intervention.

Research

Clinical and epidemiological research in environmental health addresses many variants of the same questions: Is there an association between exposure and outcome? And what interventions are effective in improving health outcomes? A focus on nature contact suggests a research agenda directed not only at potentially hazardous exposures but also at potentially healthy ones, and at outcomes that reflect not only impaired health but also enhanced health (Frumkin, 2003, 2013). If people have regular contact with flowers or trees, do they report greater well-being, better sleep, fewer headaches, reduced joint pain? Do inner-city children who attend a rural summer camp have better health during the next semester of school than their friends who spent the summer in the city? Do patients with cancer or AIDS survive longer, or have fewer infections or less pain or higher T cell counts, if they have pets? Do gardens in hospitals speed postoperative recovery? Does psychotherapy that employs contact with nature—known as ecopsychology (Roszak, Gomes, & Kanner, 1995; Buzzell & Chalquis, 2009; Kahn & Hasbach, 2012)—have an empirical basis? If these or related therapeutic approaches show promise, which patients will benefit and what kinds of contact with nature will have the greatest efficacy and cost effectiveness? (Also see Text Box 25.6.)

Answering these questions requires an orientation toward empirical research among professions, from landscape architecture to horticulture, that have traditionally not emphasized such research. It also requires an ability to define and operationalize variables currently unfamiliar to health researchers. What is exposure to nature, what does the concept of a dose mean in this context, and how do we measure it? Similarly, the outcome variables that reflect health instead of disease are less researched and need to be developed and validated. These challenges offer broad opportunities for methods development and hypothesis testing.

Collaboration

Environmental health specialists, from researchers to clinicians, have long recognized the need to collaborate with other professionals. They work with mechanical engineers to build exposure chambers, with chemists to measure exposures, and with software engineers to apply geographic information systems to health data. A focus on natural environments suggests collaborations with other kinds of professionals: landscape architects, who can help with identifying the salient features of outdoor exposures; interior designers, who can do the same for microenvironments; veterinarians, who can help with understanding human relationships with animals; and urban and regional planners, who can help with linking environmental health principles with large-scale environmental design.

Public Health Intervention

Finally, evidence of the health benefits of particular environments needs to be translated into action. On the clinical level this may have implications for patient care. Perhaps physicians and nurses will advise patients to take a few days in the country, to spend time gardening, or to adopt a pet if clinical evidence offers support for such measures. Perhaps hospitals will be built in scenic locations, and rehabilitation centers will routinely include gardens. Health promotion professionals may include nature contact among the healthy behaviors they encourage (St. Leger, 2003). Perhaps health care payers will come to fund such interventions, especially if they prove to rival pharmaceuticals in cost and efficacy. Urban planners, developers, and landscape architects may increasingly work to provide nature contact in neighborhoods, such as readily available parks, and architects may increasingly incorporate biophilic elements into building design (Text Box 25.7). In all these actions, steps to reduce any risks must also be part of implementation.

Summary

There is evidence that nature contact promotes health and well-being. This effect may have an evolutionary basis, and one or more of several mechanisms may operate. Nature contact occurs in a variety of ways and in many settings: through contact with animals and plants, through views of natural scenes such as landscapes, and through activities in green neighborhoods, parks, or wilderness areas. Programs and policies have begun to implement nature contact as a health promotion strategy. While important questions remain to be answered through research, this approach is highly promising, offering effective health promotion at low cost, with few adverse effects, and with many co-benefits.

Key Terms

- attention restoration

- Directed attention, a voluntary effort, is a finite cognitive resource, which can be depleted. Attention restoration is the replenishment of this resource; according to attention restoration theory, contact with nature is a key method of restoring attention.

- biophilia

- “The innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms” (Wilson, 1984, p. 31).

- biophilic design

- An “approach that fosters beneficial contact between people and nature in modern buildings and landscapes” (Kellert, 2008, p. 5).

- ecopsychology

- A field of psychology and a therapeutic approach rooted in the relationship between humans and nature.

- green exercise

- Exercise that takes place in natural settings such as parks and woodlands.

- nature deficit disorder

- A term coined by Richard Louv in his 2005 book, Last Child in the Woods, referring to the deprivation of nature contact that results from a lack of play and exploration in natural settings.

- wilderness therapy

- The use of wilderness activities, such as camping, for therapeutic purposes, for such conditions as mental illness, post-traumatic stress, and substance abuse (also known as adventure therapy).

Discussion Questions

- Describe your last contact with a natural setting—on a vacation, a weekend outing, or even a recent visit to a park. How did it make you feel? How would you design research to demonstrate these effects across a broad population?

- Consider the availability of parks and green space in your city or town. Are they available near the places where people live and work? Do some sections of your city or town have better access to them than others? What about poor and minority communities? Is this an environmental justice issue?

- Suppose your community is considering a land conservation initiative that would set aside tracts of green space and prohibit future development on them. Environmental advocates are leading this effort, and they ask you to support it with an argument based on public health considerations. How would you make the case?

- As described in Chapter 8, exposure assessment is a key part of any environmental epidemiology research. How would you measure exposure to nature? What is a “dose” of nature?

References

- Abram, D. (1996). The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world. New York: Vintage Books.

- Addicks, P. (2008). [Photo.] Retrieved from http://www.trishaaddicksphotography.com

- Allen, K., Blascovich, J., Wendy, B., & Mendes, W. B. (2002). Cardiovascular reactivity and the presence of pets, friends, and spouses: The truth about cats and dogs. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64, 727–739.

- American Pet Products Association. (2015). 2015–2016 APPA National Pet Owners Survey. Retrieved from http://www.americanpetproducts.org/pubs_survey.asp

- Amoly, E., Dadvand, P., Forns, J., Lopez-Vicente, M., Basagana, X., Julvez, J.,…Sunyer, J. (2014). Green and blue spaces and behavioral development in Barcelona schoolchildren: The BREATHE project. Environmental Health Perspectives, 122, 1351–1358.

- Anderson, W. P., Reid, C., & Jennings, G. (1992). Pet ownership and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Medical Journal of Australia, 157, 298–301.

- Annerstedt, M., & Währborg, P. (2011). Nature-assisted therapy: Systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39, 371–388.

- Armstrong, D. A. (2000). Survey of community gardens in upstate New York: Implications for health promotion and community development. Health & Place, 6, 319–327.

- Auerbach, P. S. (2012). Wilderness medicine (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby.

- Bancroft, C., Joshi, S., Rundle, A., Hutson, M., Chong, C., Weiss, C. C.,…Lovasi, G. (2015). Association of proximity and density of parks and objectively measured physical activity in the United States: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 138, 22–30.

- Barker, S. B., & Dawson, K. S. (1998). The effects of animal-assisted therapy on anxiety ratings of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatric Services, 49(6), 797–801.

- Beck, A. M., & Katcher, A. H. (1983). Between pets and people: The importance of animal companionship. New York: Perigree Books.

- Beck, A. M., & Meyers, N. M. (1996). Health enhancement and companion animal ownership. Annual Review of Public Health, 17, 247–257.

- Bedimo-Rung, A. L., Mowen, A. J., & Cohen, D. A. (2005). The significance of parks to physical activity and public health: A conceptual model. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28, 159–168.

- Beetz, A., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Julius, H., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 234.

- Bell, J. F., Wilson, J. S., & Liu, G. C. (2008). Neighborhood greenness and 2-year changes in body mass index of children and youth. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(6), 547–553.

- Berman, M. G., Kross, E., Krpan, K. M., Askren, M. K., Burson, A., Deldin, P. J.,…Jonides, J. (2012). Interacting with nature improves cognition and affect for individuals with depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 140(3), 300–305.

- Blair, D., Giesecke, C. C., & Sherman, S. A. (1991). Dietary, social and economic evaluation of the Philadelphia Urban Gardening Project. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 23, 161–167.

- Bodin, M., & Hartig, T. (2003). Does the outdoor environment matter for psychological restoration gained through running? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4, 141–153.

- Boseret, G., Losson, B., Mainil, J. G., Thiry, E., & Saegerman, C. (2013). Zoonoses in pet birds: Review and perspectives. Veterinary Research, 44, 36.

- Branas, C. C., Cheney, R. A., MacDonald, J. M., Tam, V. W., Jackson, T. D., & Ten Have, T. R. 2011. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. American Journal of Epidemiology, 174, 1296–1306.

- Bratman, G. N., Hamilton, J. P., & Daily, G. C. (2012). The impacts of nature experience on human cognitive function and mental health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1249, 118–136.

- Bruton, C. M., & Floyd, M. F. (2014). Disparities in built and natural features of urban parks: Comparisons by neighborhood level race/ethnicity and income. Journal of Urban Health, 91(5), 894–907.

- Buzzell, L., & Chalquis, C., (Eds.). (2009). Ecotherapy: Healing with nature in mind. Berkeley, CA: Counterpoint Press.

- Caras, R. A. (1996). A perfect harmony: The intertwining lives of animals and humans throughout history. New York: Fireside.

- Cariñanos, P., & Casares-Porcel, M. (2011). Urban green zones and related pollen allergy: A review; Some guidelines for designing spaces with low allergy impact. Landscape and Urban Planning, 101, 205–214.

- Carter, M., & Horwitz, P. (2014). Beyond proximity: The importance of green space useability to self-reported health. EcoHealth, 11(3), 322–332.

- Chawla, L., Keena, K., Pevec, I., & Stanley, E. (2014). Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence. Health & Place, 28, 1–13.

- Cherniack, E. P., & Cherniack, A. R. (2014). The benefit of pets and animal-assisted therapy to the health of older individuals. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2014, 623203.

- Cimprich, B., & Ronis, D. L. (2003). An environmental intervention to restore attention in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 26, 284–292.

- Cleland, V., Crawford, D., Baur, L. A., Hume, C., Timperio, A., & Salmon, J. (2008). A prospective examination of children's time spent outdoors, objectively measured physical activity and overweight. International Journal of Obesity, 32(11), 1685–1693.

- Clutton-Brock, J. (1981). Domesticated animals from early times. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Cohen, D. A., McKenzie, T. L., Sehgal, A., Williamson, S., Golinelli, D., & Lurie, N. (2007). Contribution of public parks to physical activity. American Journal of Public Health, 97(3), 509–514.

- Cohen-Cline, H., Turkheimer, E., & Duncan, G. E. (2015). Access to green space, physical activity and mental health: A twin study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(6), 523–529.

- Cotton, S., & Butselaar, F. (2013). Outdoor adventure camps for people with mental illness. Australasian Psychiatry, 21(4), 352–358.

- Cranz, G. (1982). The politics of park design: A history of urban parks in America. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Crompton, J. L. (2005). The impact of parks on property values: Empirical evidence from the past two decades in the United States. Managing Leisure, 10(4), 203–218.

- Cumes, D. (1998a). Inner passages outer journeys: Wilderness, healing, and the discovery of self. Minneapolis: Llewellyn.

- Cumes, D. (1998b). Nature as medicine: The healing power of the wilderness. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 4, 79–86.

- Dadvand, P., Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Esnaola, M., Forns, J., Basagaña, X., Alvarez-Pedrerol, M.,…Sunyer, J. (2015). Green spaces and cognitive development in primary schoolchildren. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States, 112, 7937–7942.

- Dadvand, P., Sunyer, J., Basagana, X., Ballester, F., Lertxundi, A., Fernandez-Somoano, A.,…Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2012). Surrounding greenness and pregnancy outcomes in four Spanish birth cohorts. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(10), 1481–1487.

- Dharmage, S. C., Lodge, C. L., Matheson, M. C., Campbell, B., & Lowe, A. J. (2012). Exposure to cats: Update on risks for sensitization and allergic diseases. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 12(5), 413–423.

- Diette, G. B., Lechtzin, N., Haponik, E., Devrots, A., & Rubin, H. R. (2003). Distraction therapy with nature sights and sounds reduces pain during flexible bronchoscopy. Chest, 123, 941–948.

- Doxey, J. S., Waliczek, T. M., & Zajicek, J. M. (2009). The impact of interior plants in university classrooms on student course performance and on student perceptions of the course and instructor. HortScience, 44(2), 384–391.

- Elad, D. (2013). Immunocompromised patients and their pets: Still best friends? Veterinary Journal, 197(3), 662–669.

- Endenburg, N., & van Lith, H. A. (2011). The influence of animals on the development of children. Veterinary Journal, 190(2), 208–214.

- Escobedo, F. J., Kroeger, T., & Wagner, J. E. (2011). Urban forests and pollution mitigation: Analyzing ecosystem services and disservices. Environmental Pollution, 159(8–9), 2078–2087.

- Faber Taylor, A., Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2002). Views of nature and self-discipline: Evidence from inner city children. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22, 49–63.

- Fleishman-Hillard Research. (2007). Pet spending survey. Retrieved from http://cdn.fleishmanhillard.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/01/Fleishman-Hillard-Pet-Spending-Survey.pdf

- Fox, S. (1981). John Muir and his legacy. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Fredrickson, L. M., & Anderson, D. H. (1999). A qualitative exploration of the wilderness experience as a source of spiritual inspiration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19, 21–39.

- Friedmann, E., & Son, H. (2009). The human-companion animal bond: How humans benefit. Veterinary Clinics of North America—Small Animal Practice, 39(2), 293–326.

- Friedmann, E., & Thomas, S. A. (1995). Pet ownership, social support, and one-year survival after acute myocardial infarction in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). American Journal of Cardiology, 76, 1213–1217.

- Frumkin, H. (2003). Healthy places: Exploring the evidence. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1451–1456.

- Frumkin, H. (2013). The evidence of nature and the nature of evidence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44, 196–197.

- Greenway, R. (1995). The wilderness effect and ecopsychology. In T. Roszak, M. E. Gomes, & A. D. Kanner (Eds.), Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind (pp. 122–135). San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

- Gobster, P. (2002). Managing urban parks for a racially and ethnically diverse clientele. Leisure Sciences, 24, 143–159.

- Haller, R. L., & Kramer, C. L. Horticultural therapy methods: Making connections in health care, human service, and community programs. Philadelphia: Haworth Press, 2006.

- Hamilton, E., & Cairns, H. (Eds.). (1961). Plato: The collected dialogues. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961.

- Han, B., Cohen, D. A., Derose, K. P., Marsh, T., Williamson, S., & Raaen, L. (2014). How much neighborhood parks contribute to local residents' physical activity in the City of Los Angeles: A meta-analysis. Preventive Medicine, 69(Suppl. 1), S106–110.

- Han, K.-T. (2009). Influence of limitedly visible leafy indoor plants on the psychology, behavior, and health of students at a junior high school in Taiwan. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 658–692.

- Harris, N., Minniss, F. R., & Somerset, S. (2014). Refugees connecting with a new country through community food gardening. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(9), 9202–9216.

- Hartig, T., Mitchell, R., de Vries, S., & Frumkin, H. (2014). Nature and health. Annual Review of Public Health, 35, 207–228.

- Heerwagen, J. H., & Orians, G. H. (1993). Humans, habitats, and aesthetics. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 138–172). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Heerwagen, J. H., & Orians, G. H. (2002). The ecological world of children. In P. H. Kahn Jr. & S. R. Kellert (Eds.), Children and nature: Psychological, sociocultural, and evolutionary investigations (pp. 29–63). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Ho, C.-H., Sasidharan, V., Elmendorf, W., Willits, F. K., Graefe, A., & Godbey, G. (2005). Gender and ethnic variations in urban park preferences, visitation, and perceived benefits. Journal of Leisure Research, 37, 281–306.

- Holtan, M. T., Dieterlen, S. L., & Sullivan, W. C. (2014). Social life under cover: Tree canopy and social capital in Baltimore, Maryland. Environment and Behavior, 47(5), 502–525.

- Honeyman, M. K. (1992). Vegetation and stress: A comparison study of varying amounts of vegetation in countryside and urban scenes. In D. Relf (Ed.), The role of horticulture in human well–being and social development (pp. 143–145). Portland, OR: Timber Press.

- Hull, R. B., & Revell, G.R.B. (1989). Cross-cultural comparison on landscape scenic beauty evaluations: A case study in Bali. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 9, 177–191.

- Hunt, M., Al-Awadi, H., & Johnson, M. (2008). Psychological sequelae of pet loss following Hurricane Katrina. Anthrozoös, 21(2), 109–121.

- Hunter, N. L. (1970). Horticulture programs in prisons. San Luis Obispo: California State Polytechnic College, Horticulture Department.

- Hüttenmoser, M. (1995). Children and their living surroundings: Empirical investigations into the significance of living surroundings for the everyday life and development of children. Children's Environments, 12, 403–413.

- Kahn, P. H., Jr., & Hasbach, P. H. (Eds.). (2012). Ecopsychology: Science, totems, and the technological species. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kahn, P. H., Jr., & Kellert, S. R. (Eds.). (2002). Children and nature: Psychological, sociocultural, and evolutionary investigations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kamioka, H., Tsutani, K., Yamada, M., Park, H., Okuizumi, H., Honda, T.,…Mutoh, Y. (2014). Effectiveness of horticultural therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 22(5), 930–943.

- Kaplan, R. (1983). The role of nature in the urban context. In I. Altman & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Human behavior and environment: Vol. 6. Behavior and the natural environment (pp. 127–161). New York: Plenum.

- Kaplan, R. (1993). The role of nature in the context of the workplace. Landscape and Urban Planning, 26, 193–201.

- Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., & Ryan, R. L. (1998). With people in mind: Design and management of everyday nature. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 169–182.

- Kaplan, S. (2001). Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior, 33, 480–506.

- Kaplan, S., & Berman, M. G. (2010). Directed attention as a common resource for executive functioning and self-regulation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(1), 43–57.

- Kardan, O., Gozdyra, P., Misic, B., Moola, F., Palmer, L. J., Paus, T., & Berman, M. G. (2015). Neighborhood greenspace and health in a large urban center. Scientific Reports, 5. doi:10.1038/srep11610

- Kareiva, P., Tallis, H., Ricketts, T. H., Daily, G. C., & Polasky, S. (2011). Natural capital: Theory and practice of mapping ecosystem services. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kaźmierczak, A. (2013). The contribution of local parks to neighbourhood social ties. Landscape and Urban Planning, 109(1), 31–44.

- Kellert, S. R. (1993). The biological basis for human values of nature. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 42–69). Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Kellert, S. R. (2008). Dimensions, elements, and attributes of biophilic design. In S. R. Kellert, J. Heerwagen, & M. Mador (Eds.), Biophilic design: The theory, science and practice of bringing buildings to life (pp. 3–19). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Kemperman, A., & Timmermans, H. (2014). Green spaces in the direct living environment and social contacts of the aging population. Landscape and Urban Planning, 129, 44–54.

- Kirkby, M. (1989). Nature as refuge in children's environments. Children's Environments Quarterly, 6, 7–12.

- Korpela, K., & Hartig, T. 1996. Restorative qualities of favorite places. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 16, 221–233.

- Kuo, F. E. (2001). Coping with poverty: Impacts of environment and attention in the inner city. Environment and Behavior, 33(1), 5–34.

- Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2001a). Aggression and violence in the inner city: Effects of environment via mental fatigue. Environment and Behavior, 33(4), 543–571.

- Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2001b). Environment and crime in the inner city: Does vegetation reduce crime? Environment and Behavior, 33(3), 343–367.

- Kuo, F. E., & Taylor, A. F. (2004). A potential natural treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Evidence from a national study. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 1580–1586.

- Larsen, L., Adams, J., Deal, B., Kweon, B. S., & Tyler, E. (1998). Plants in the workplace: The effects of plant density on productivity, attitudes, and perceptions. Environment and Behavior, 30(3), 261–281.

- Lederbogen, F., Kirsch, P., Haddad, L., Streit, F., Tost, H., Schuch, P.,…Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2011). City living and urban upbringing affect neural social stress processing in humans. Nature, 474(7352), 498–501.

- Levine, G. N., Allen, K., Braun, L. T., Christian, H. E., Friedmann, E., Taubert, K. A.,…Lange, R. A. (2013). Pet ownership and cardiovascular risk: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 127, 2353–2363.

- Lewis, C. A. (1990). Gardening as healing process. In M. Francis & R. T. Hester (Eds.), The meaning of gardens (pp. 244–251). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs. (n.d.). American conservationist John Muir (1838–1914) [Photo]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Muir.jpg

- Lodge, C. J., Allen, K. J., Lowe, A. J., Hill, D. J., Hosking, C. S., Abramson, M. J., & Dharmage, S. C. (2012). Perinatal cat and dog exposure and the risk of asthma and allergy in the urban environment: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Clinical and Developmental Immunology, 2012, 176484.

- Lohr, V. I. (2010). What are the benefits of plants indoors and why do we respond positively to them? Acta Horticulturae, 881(2), 675–682.

- Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature-deficit disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Press.

- Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., de Vries, S., Spreeuwenberg, P., Schellevis, F. G., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2009). Morbidity is related to a green living environment. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 63, 967–973.

- Mani, I., & Maguire, J. H. (2009). Small animal zoonoses and immunocompromised pet owners. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine, 24, 164–174.

- Marcus, C. C. (2007). Healing gardens in hospitals. Interdisciplinary Design and Research e-Journal, 1(1).

- Marcus, C. C., & Sachs, N. A. (2013). Therapeutic landscapes: An evidence-based approach to designing healing gardens and restorative outdoor spaces. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Marcus, D. A. (2013). The science behind animal-assisted therapy. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 17(4), 322.

- Marselle, M. R., Irvine, K. N., & Warber, S. L. (2013). Walking for well-being: Are group walks in certain types of natural environments better for well-being than group walks in urban environments? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10(11), 5603–5628.

- Matchock, R. L. (2015). Pet ownership and physical health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28, 386–92

- Mattson, R. H. (1992). Prescribing health benefits through horticultural activities. In D. Relf (Ed.), The role of horticulture in human well-being and social development (pp. 161–168). Portland, OR: Timber Press.

- McConnell, A. R., Brown, C. M., Shoda, T. M., Stayton, L. E., & Martin, C. E. (2011). Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1239–1252.

- McLuhan, T. C. (1994). The way of the earth: Encounters with nature in ancient and contemporary thought. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- McNicholas, J., Gilbey, A., Rennie, A., Ahmedzai, S, Dono, J. A., & Ormerod, E. (2005). Pet ownership and human health: A brief review of evidence and issues. BMJ, 331(7527), 1252–1254.

- Mitchell, R. (2013). Is physical activity in natural environments better for mental health than physical activity in other environments? Social Science & Medicine, 91, 130–34

- Mitchell, R., & Popham, F. (2008). Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: An observational population study. Lancet, 372, 1655–1660.

- Mitchell, R. J., Richardson, E. A., Shortt, N. K., & Pearce, J. R. (2015). Neighborhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental well-being. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(1), 80–84.

- Moore, E. O. (1981–1982). A prison environment's effect on health care service demands. Journal of Environmental Systems, 11, 17–34.

- Morris, D. O. (2010). Human allergy to environmental pet danders: A public health perspective. Veterinary Dermatology, 21(5), 441–449.

- Muir, J. (1901). Our national parks. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Muñoz Lasa, S., Ferriero, G., Brigatti, E., Valero, R., & Franchignoni, F. (2011). Animal-assisted interventions in internal and rehabilitation medicine: A review of the recent literature. Panminerva Medica, 53(2), 129–136.

- Nabhan, G. P., & Trimble, S. (1994). The geography of childhood: Why children need wild places. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Nash, R. (1982). Wilderness and the American mind (3rd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Natterson-Horowitz, B., & Bowers, K. (2013). Zoobiquity: The astonishing connection between human and animal health. New York: Vintage.

- Neese, R. (1959). Prisoners escape. Flower Grower, 46, 39–40.

- Nicklett, E. J., Anderson, L. A., & Yen, I. H. (2014). Gardening activities and physical health among older adults: A review of the evidence. Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi:10.1177/0733464814563608

- Nowak, D. J., Hirabayashi, S., Bodine, A., & Greenfield, E. (2014). Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States. Environmental Pollution, 193, 119–129.

- O'Haire, M. E. (2013). Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1606–1622.

- Olmsted, F. L. (1999). Public parks and the enlargement of towns. In R. T. LeGates & F. Stout (Eds.), The city reader (2nd ed., pp. 314–320). London: Routledge. (Originally published 1870)

- Orsega-Smith, E., Mowen, A., Payne, L., & Godbey, G. (2004). The interaction of stress and park use on psycho-physiological health in older adults. Journal of Leisure Research, 36, 232–257.

- Payne, L., Orsega-Smith, E., Godbey, G., & Roy, M. (1998). Local parks and the health of older adults: Results from an exploratory study. Parks & Recreation, 33(10), 64–70.

- Pearson-Mims, C. H., & Lohr, V. I. (2000). Reported impacts of interior plantscaping in office environments in the United States. HortTechnology, 10(1), 82–86.

- Perlman, M. (1994). The power of trees: The reforesting of the soul. Woodstock, CT: Spring.

- Purcell, A. T., Lamb, R. J., Mainardi Peron, E., & Falchero, S. (1994). Preference or preferences for landscape? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 14, 195–209.

- Ray, H., & Jakubec, S. L. (2014). Nature-based experiences and health of cancer survivors. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 20(4), 188–192.

- Roszak, T., Gomes, M. E., & Kanner, A. D. (Eds.). (1995). Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

- Russell, K. C. (2001). What is wilderness therapy? Journal of Experiential Education, 24(2), 70–79.

- Russell, K. C., & Phillips-Miller, D. (2002). Perspectives on the wilderness therapy process and its relation to outcome. Child & Youth Care Forum, 31(6), 415–437.

- Saberi, P., Neilands, T. B., & Johnson, M. O. (2014). Association between dog guardianship and HIV clinical outcomes. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care, 13(4), 300–304.

- Sacks, O. (1984). A leg to stand on. New York: HarperCollins.

- St. Leger, L. (2003). Health and nature—new challenges for health promotion [Editorial]. Health Promotion International, 18, 173–175.

- Sartelet, K. N., Couvidat, F., Seigneur, C., & Roustan, Y. (2012). Impact of biogenic emissions on air quality over Europe and North America. Atmospheric Environment, 53, 131–141.

- Schaefer, L., Plotnikoff, R. C., Majumdar, S. R., Mollard, R., Woo, M., Sadman, R.,…McGavock, J. (2014). Outdoor time is associated with physical activity, sedentary time, and cardiorespiratory fitness in youth. Journal of Pediatrics, 165(3), 516–521.

- Schroeder, H. W., & Green, T. L. (1985). Public preference for tree density in municipal parks. Journal of Arboriculture, 11, 272–277.

- Schukoske, J. E. (2000). Community development through gardening: State and local policies transforming urban open space. Legislation and Public Policy, 3, 351–393.

- Serpell, J. (1991). Beneficial effects of pet ownership on some aspects of human health and behaviour. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 84, 717–720.

- Sherer, P. M. (2006). The benefits of parks: Why America needs more city parks and open space. Trust for Public Land. Retrieved from https://www.tpl.org/benefits-parks-white-paper

- Shniderman, C. M. (1974). Impact of therapeutic camping. Social Work, 19, 354–357.

- Siegel, J. (1990). Stressful life events and use of physician services among the elderly: The moderating role of pet ownership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1081–1086.

- Simons, L. A., Simons, J., McCallum, J., & Friedlander, Y. (2006). Lifestyle factors and risk of dementia: Dubbo Study of the elderly. Medical Journal of Australia, 184, 68–70.

- Simson, S., & Straus M. C. (2003). Horticulture as therapy: Principles and practice. Philadelphia: Haworth Press.

- Smallwood, J., & Ownby, D. (2012). Exposure to dog allergens and subsequent allergic sensitization: An updated review. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 12(5), 424–428.

- Stanley, I. H., Conwell, Y., Bowen, C., & Van Orden, K. A. (2014). Pet ownership may attenuate loneliness among older adult primary care patients who live alone. Aging & Mental Health, 18(3), 394–399.

- Stark, J. H., Neckerman, K., Lovasi, G. S., Quinn, J., Weiss, C. C., Bader, M.D.M.,…Rundle, A. (2014). The impact of neighborhood park access and quality on body mass index among adults in New York City. Preventive Medicine, 64, 63–68.

- Stull, J. W., & Stevenson, K. B. (2015). Zoonotic disease risks for immunocompromised and other high-risk clients and staff: Promoting safe pet ownership and contact. Veterinary Clinics of North America—Small Animal Practice, 45(2), 377–392.

- Takano, T., Nakamura, K., & Watanabe, M. 2002. Urban residential environments and senior citizens' longevity in megacity areas: The importance of walkable green spaces. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 913–918.

- Taylor, A. F., Kuo, F. E., & Sullivan, W. C. (2002). Views of nature and self-discipline: Evidence from inner city children. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22, 49–63.

- Tennessen, C. M., & Cimprich, B. (1995). Views to nature: Effects on attention. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15, 77–85.

- Thompson Coon, J., Boddy, K., Stein, K., Whear, R., Barton, J., & Depledge, M. H. (2011). Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environmental Science & Technology, 45, 1761–1772.

- Toohey, A. M., McCormack, G. R., Doyle-Baker, P. K., Adams, C. L., & Rock, M. J. (2013). Dog-walking and sense of community in neighborhoods: Implications for promoting regular physical activity in adults 50 years and older. Health & Place, 22, 75–81.

- Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224, 420–421.

- Ulrich, R. S. (1993). Biophilia, biophobia, and natural landscapes. In S. R. Kellert & E. O. Wilson (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis (pp. 73–137). Washington, DC: Island Press.