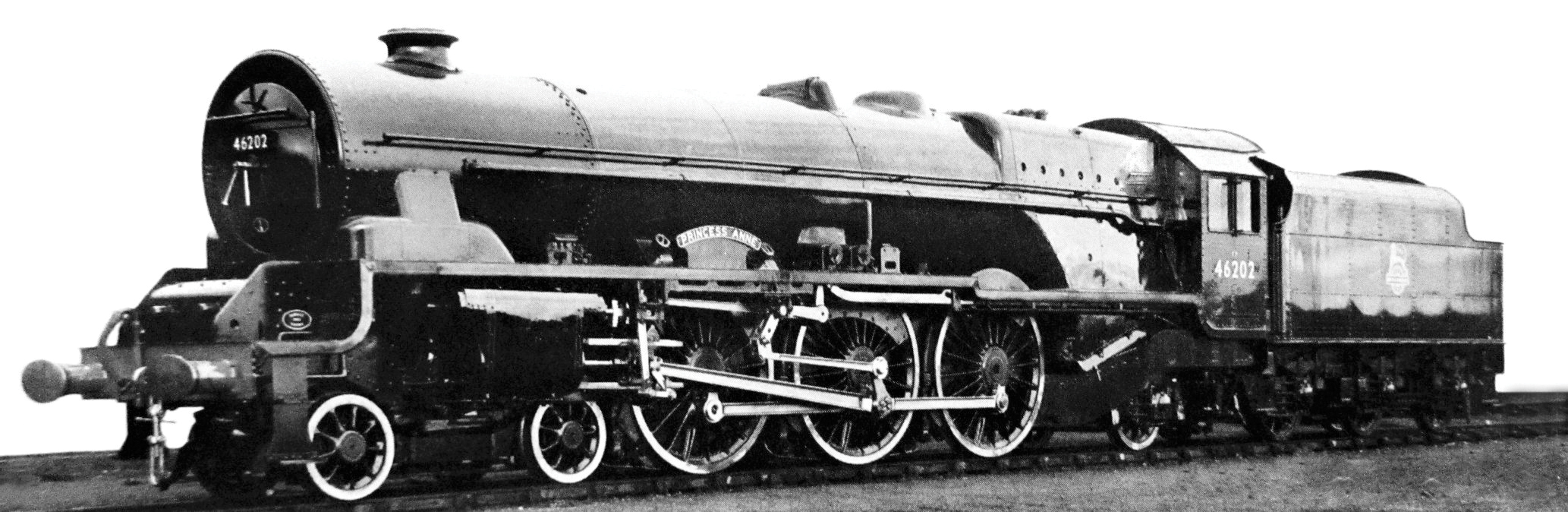

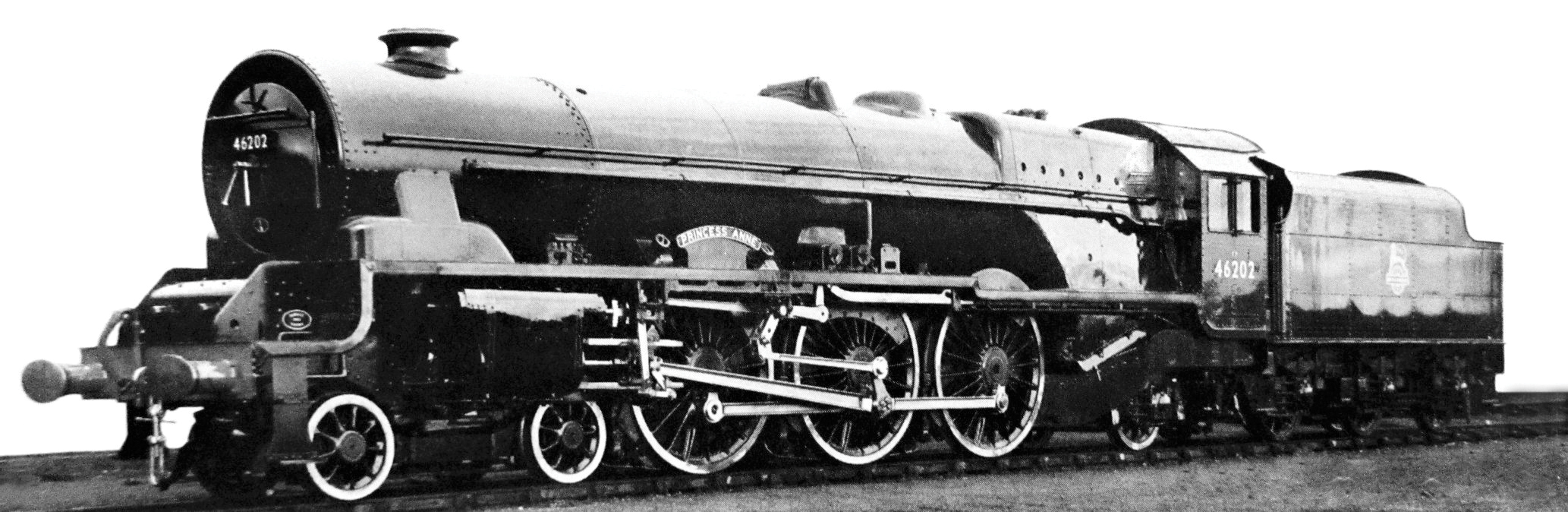

August 1952 – 46202 emerges from Crewe Works in her new guise, a hybrid – part Princess Royal and part Princess Coronation – painted in BR green. (RH/BR)

When Turbomotive entered Crewe Works in May 1950 few expected her to reappear quickly, based on the pattern of past maintenance periods. Added to this it seems that she may have failed in the days before her time in works began. But no official records appear to have survived to confirm this and no unofficial sightings have come to light either. However, part of any heavy general repair cycle is to strip down the locomotive, examine all working parts and replace or repair those badly worn. Being a unique engine where there was little or no past history or collective experience to fall back on, no one could predict, with any certainty, what state the turbine system would be in. Repair might not be possible and a costly new build or reconditioning might be the only options available.

The LMS, and later the new British Rail regime, had both reached the conclusion that the turbine experiment, though of interest, had now run its course. Although she ran effectively and equalled the performance of her sisters, there seems to have been little opposition to her remaining in service, but a prolonged period in the workshops gave BR a reason to consider her future: break her down for spares or convert her into a reciprocating engine.

August 1952 – 46202 emerges from Crewe Works in her new guise, a hybrid – part Princess Royal and part Princess Coronation – painted in BR green. (RH/BR)

When the LMS had considered ways in which the Princess Class might be improved, in the late 1930s, Derby Drawing Office came up with a series of modifications. The plans were shelved and work began on the Coronation Class instead, but the earlier work had not been forgotten and lay in the archives at Derby, periodically reviewed in case a problem occurred with a member of the class necessitating a major rebuild.

46202 was dismantled and surveyed at Crewe, and the turbine and gears were dispatched to Metrovick for specialist analysis.

The survey took a short time, but the results took much longer to be considered before firm proposals for her future were put forward. In summary, the report concluded that repair work for all but the turbine system was routine and manageable. Despite the size of his task in bringing the four railway companies under the BR banner and achieve standardisation of operation and development, Robert Riddles became personally involved in 46202’s future. In the limited correspondence that survives, marking the progress of these discussions, his name appears many times – for his comment or simply as an information addressee. His interest in the fate of one locomotive, out of many thousands under his control, is remarkable.

On 20 April 1951 the Chief Regional Officer of the Midland Region, J.W. Watkins, wrote a memo to the Railway Executive, based on internal memos from various less senior officers. In it he summarised the results of 46202’s survey and financial implications, then recommended a course of action:

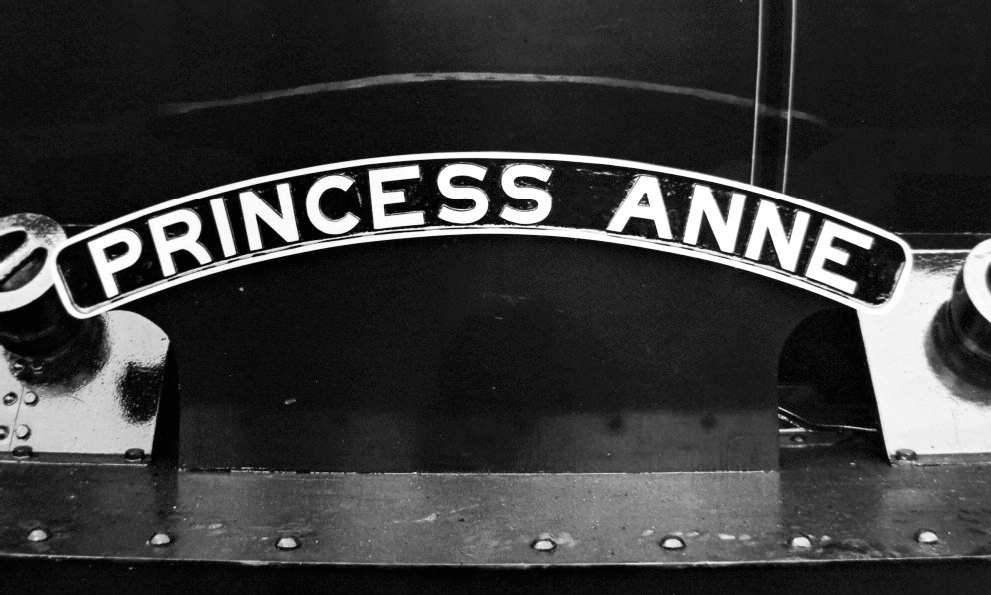

Named Princess Anne and being made ready for duty. (RH/BR)

‘Turbine Geared Driven Locomotive No 46202

‘The locomotive renewal programme for 1933, authorised by the LMS Board in July 1932, included the construction of 3 4-cylinder 4-6-2 class passenger engines. In February 1933 the LMS Board gave approval to one of these locomotives being fitted with a Lysholm-Smith Ljungstrom turbine in place of the conventional reciprocating type of driving gear. The purpose of fitting this equipment was to compare the turbine type propulsion with the reciprocating type fitted to the other two engines authorised in the programme referred to. The three engines have the same wheel base.

‘During the time the turbine locomotive has been in service there have been several failures of the turbine and transmission, and last year a further failure occurred affecting the bearings of the transmission [this is the only reference to this failure that appears to have survived]. To make the locomotive suitable for service it will be necessary to incur the costs for the repair of turbine parts which Metropolitan-Vickers, who designed and supplied the turbines, estimate at £460. In addition to this a further expenditure will be necessary of £360, making a total expenditure of £820.

‘Metropolitan-Vickers point out that apart from the cost, the turbines on this locomotive have now reached a stage when after another period of service they will require extensive repairs. The firm are not prepared to give an estimate of the costs of this work, but the Chief Mechanical Engineer considers that this will be very considerable.

‘In view of the expense and the fact that it has always been necessary to carry a fitter on the locomotive in addition to the ordinary crew, if trouble is to be avoided, which involves an expenditure of about £500 per annum, it would appear that the time is opportune for the engine to be converted into a normal reciprocating type driven locomotive. It has run 439,931 miles since being built, about 1935, and it is felt that sufficient knowledge of its capabilities has been obtained over the years it has been in service. Furthermore, having regard to its record there does not appear to be any question of any more locomotives of this type being built.

‘The approximate estimated cost of converting the turbine locomotive to one of a normal reciprocating type is £6,250 as compared with the expenditure of £820 immediately necessary if the locomotive is to continue to operate in its present form. For the net additional outlay of £5430 there would be an assured saving of approximately £500 per annum (or 9.2% of the net outlay) on the wages of the fitter.

‘It is, therefore, recommended that turbine locomotive No 46202 should be converted to one of a normal reciprocating type at an estimated outlay of £6250, and it is understood Mr Riddles agrees with this proposal.’

On 17 May 1951 the proposal was discussed at the Railway Executive’s Board Meeting and approval given to proceed. The RE gave the project the registered number of WM 1010. In his memo to the Chief Regional Officer of the Midland Region, authorising this work, the Chairman added a specific instruction:

‘I should be pleased if you could kindly advise me when the work of conversion is started and, also, when it is completed.’

It seems strange that full RE Board approval for such a small project was thought necessary. With a massive building programme set to deliver 999 new locomotives already underway at a projected cost in excess of £20 million, with ongoing work to support this huge network and its existing rolling stock and with drawing offices and workshops trying to get all this work done, it is remarkable that the organisation found time to debate and plan the future of one engine. The simple and cheapest course open to Midland Region was to go ahead with fairly low-cost repairs and modify the engine to remove the need for a fitter. The alternative was to withdraw her from service and, if her state was deemed so poor as to make continued running a problem, use her for spares.

The LMS had developed a sound method of economic analysis that underpinned new proposals and projects. It was a system that became imbedded in all they did and Riddles, as the LMS’s disciple, brought these processes to British Rail. But in the proposals for 46202, of which he was a part, wellestablished cost–benefit accounting principles seemed to have been ignored, replaced by something more akin to a ‘back of a fag packet’ calculation – there is only one option and that is what it will cost. In truth there were easier and cheaper options, especially as the locomotive seemed to be operating as well as, or better than, her sisters in the twelve months before her latest visit to Crewe.

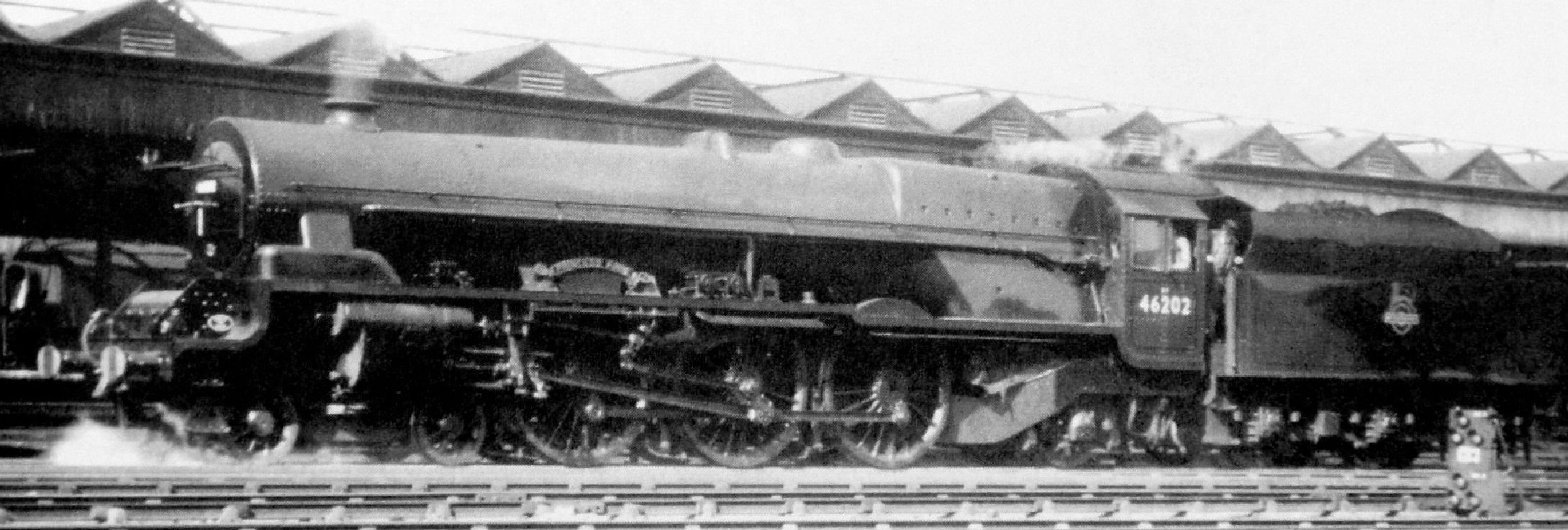

46202 arrives at Euston for the first time. The LMR’s Chief Regional Officer, J.W. Watkins, greets the Driver, Sam Mason, and Fireman, Chris Brereton. (RH/BR)

Against this background Metrovick’s own summary of work needed on the turbine makes interesting reading. In his memo to the Board, Watkins painted a gloomy picture of the turbine’s condition and potential repair costs suggesting that after ‘another period of service they will require extensive repairs’. In reality Metrovick were more upbeat, judging that the fixed turbine blades and rotors might need to be renewed and corrosion to the turbine casings repaired ‘in a few years’ time’. They did not estimate the value of this work because they felt that ‘the requirement is too far in the future, and as yet unclear, to adequately judge the state of machinery and the likely cost’.

In any organisation costings will often be managed to reflect preconceived ideas or pre-selected solutions. Turbomotive was no longer needed and, under the guise of a sound management decision, quickly dispatched. The decision to rebuild her at high cost, set to rise to £8,774, seems unjustified in the face of a substantial locomotive building programme already well underway and the heavy workload being borne by the workshops. So, perhaps it was simply a case of Riddles wishing to preserve this lone example of his mentor’s innovative work and pulling strings to make sure she survived in this new guise. We shall never know, but it is pleasing to think that Riddles might have felt this way.

The 1936 plans for developing the Princess Class became the basis for 46202’s conversion. It soon became apparent that the work recommended would turn her into a Princess Royal/Coronation hybrid. She would keep her 6ft 6in wheels, but have main frames modified with a Coronation Class front end. The inside cylinders would be cast steel, the outside ones cast iron, with a set of motion all to the Coronation design. The crank axles, smokebox fittings and superheater header and elements would be built to a new design. The boiler would be an existing Type 1, with sloping throat plate modified with the regulator in the dome. The original cab was reused, suitably modified to take the reversing gear.

Re-absorbed into Camden’s allocation and ready for duty. (ET/RH)

It will soon be autumn as 46202 prepares to leave Euston with the early morning express to Liverpool. (RH/BR)

With such a heavy workload Derby Drawing Office struggled to get this additional design work done. It was not until February 1952 that they found time to complete the task. By May the drawings were complete, materials ordered and work scheduled to start, but not quick enough for Watkins, who, under pressure from Riddles, sent a number of personal hasteners to John Harrison, then Mechanical and Electrical Engineer for the Midland Region at Derby. On 31 October 1951, for example, he wrote:

‘I shall be glad to know whether this work has been started and, if so, on what date, and also when you anticipate it will be finished.’

Harrison responded a month later:

‘In reply to your letter of the 31st October, the work of converting locomotive No 46202 to normal reciprocating type drive has not commenced and I regret I am not in a position to state when it will be taken in hand. It will be some time before it is possible to complete the necessary drawings connected with the conversion and as I have explained to Mr Riddles my Drawing Office Staff are at the present time fully occupied in the completion of drawings for certain of the new BR Standard Locomotives.’

A classic Eric Treacy photo. It almost seems that the crew have deliberately posed the loco for best effect. (ET/RH)

No longer the fairly hushed getaway of Turbomotive but the full thrust of a traditional steam locomotive, here leaving Crewe. The few drivers and firemen who had driven 46202 in both forms tended to prefer the turbine version. (RH)

Finally work began and took little more than three months to complete. 46202 was sandwiched on the production line between the first batch of twenty-five new standard class Pacifics and LMS locomotives in various states of repair at Crewe. On 13 August 1952 she was rolled out of No 10 Erecting Shop, seemingly having been painted in green livery on the production line, not in the Paint Shop. If so, this was unusual, but might reflect the heavy workload that staff at Crewe faced.

After seventeen years of service the locomotive was finally named and followed the pattern set by her twelve sisters. While under construction Royal approval was sought to name her Princess Anne. When 46202 re-entered service on 15 August, the young princess’s second birthday, a formal but lowkey naming ceremony took place. No records seem to have survived describing who attended and there are no photographs either of the event. All we have are a small number of pictures taken of her in ex-works condition, resplendent in her new colour scheme, workmen giving her an additional high-gloss polish ready for service.

A running-in period quickly began and she was noted several times on the main line and at Shrewsbury station, a regular route for engines just out of the works and under test. Finally, after more than two years away, 46202 returned to her allocated shed at Camden late in August, where she was ‘spotted’ by an RCTS observer:

At speed near Tamworth, thundering through the Trent Valley. (RH)

Power and majesty at Hatton. (RP)

‘August 1952.…. The outside cylinders are set further forward than the other Princesses and the steam pipes have a distinctive bulbous casing similar to that of the Duchesses. The inside cylinders are of cast steel. No smoke deflectors are fitted. It carries works plates “Rebuilt Crewe 1952” and is back on its old Turbine duty, the 0830 Euston to Liverpool.’

46202 passing Hatton with the Liverpool Euston express in September 1952. (RP)

Waiting to pick up her load. (RR/RH)

There was little fanfare or publicity surrounding her return, a far cry from her launch in 1935. On arriving at Euston for the first time, Watkins met the loco and was photographed shaking the hands of her crew, Driver Sam Mason and Fireman Chris Brereton. So she slipped back into service without fuss or particular interest. But those who saw her were impressed by the look of the rebuilt engine, which seemed to combine the best features of the Princess Royal and Coronation Classes. As Turbomotive she had been unique and remained so in this new, more traditional guise. Although largely unannounced by BR and unnoticed by the railway press, footplate crew at Camden and Edge Hill showed great interest and still regarded her as a glamorous locomotive. Bill Starvis, a top link driver at Camden, who had worked on Turbomotive in 1949 and 1950 and been greatly impressed by her, later recalled his thoughts on the new 46202:

‘I didn’t get to drive her but spent time looking over the engine when she arrived at Camden in ‘52. If she had survived I would probably have taken her out on the road at some stage. She was a good looking loco, more like the non-streamlined Duchesses that appeared pre-war before they were fitted with smoke deflectors, but the Princesses look hadn’t gone away. I’m told, by those who did work her, that she performed well, but not as good as the turbo – early days though and she didn’t get any time to really prove herself. We all regarded her as something special and all hoped to be given the chance to drive her.’

46202 topped off with coal at Edge Hill and ready to back down to Lime Street. (ET/RH)

The Euston to Liverpool route had been specifically chosen for Turbomotive because it suited her performance best – few stops and as much continuous, fast running as possible. With rebuilding, this policy could have ended but the Princesses tended to work this route and so she returned to her old stamping ground. In time, as Motive Power Depots gained experience of this ‘new’ locomotive with the capabilities of a Duchess, her pattern of work might have changed, but first she had to prove herself in day-to-day service.

A very grimy 46202 preparing to leave Edgehill with the Red Rose to Euston September 1952. (RP)

If successful, there was a good chance that some or all of the modifications could have been extended to the other members of the Princess Class. There was concern in some quarters that their performance was significantly below the Coronations and rebuilding, when starting a period of major maintenance, was deemed a practical solution. But the cost, if the proposal had ever been more than conjecture, ruled out any change and the Princesses continued as they were, with only minimal modifications, until withdrawn from service in the early 1960s.

There was talk of smoke deflectors being fitted to 46202 soon after arriving at Camden, to correct a drifting smoke problem that obscured the footplate crews’s forward view. If completed, it would have increased the resemblance of this hybrid engine to her half-sisters, as well as correcting a problem that often beset steam locomotives. Starvis wondered why they had not been fitted when she was being rebuilt at Crewe and reasoned that it was an oversight due to pressure of other work.

During the few weeks remaining to her, 46202 plied her trade between London and Liverpool making the return trip successfully twenty-eight times, being photographed quite often by line-side spotters. No stronger attention came her way and she slipped into the comparative obscurity of being just another Pacific – wonderful to see in full flow and still unique, but the novelty would soon wear off. Turbomotive had drawn attention throughout her seventeen years of life – railwaymen and lay people continually fascinated by her distinctive looks and her experimental state. She remained an icon to the last, stimulated by the very human need to consider and enjoy novel concepts, then mull over ‘what might have been’ if only engineers had been braver when new ideas evolved.

Princess Anne would find another sort of fame two months after rebuilding, in a way no one could expect. On 8 October she was again rostered to take the 08.00 train to Liverpool and so began her penultimate journey.