CHAPTER 4

THE BRAIN’S JOURNEY FROM PREGNANCY TO MENOPAUSE

WHEN I STARTED WORKING IN the field of Alzheimer’s, I never would have thought that one day I’d be researching hormonal changes, let alone writing a book about them. Although it’s long been known that hormones impact brain health, evidence of a firm connection between hormonal health and women’s cognitive fitness is a relatively recent discovery. Our hormones have turned out to be even more of an ally, and their decline even more of a problem, than previously thought.

This is not to say that a woman’s behavior is governed by her hormones. It is clear that our hormones do not dictate gender differences, and gender stereotyping is both limited and limiting in nature. Our biological heritage is but one force that interacts with many others, combining with emotional, cultural, and societal factors, not to mention our character and self-expression. With that in mind, acknowledging the powerful effects hormones can have on a woman’s brain and body won’t hold us back—it will instead empower us to make more informed decisions backed by science. Having better knowledge of how our brains really work is a vital step that can widen the breadth and sharpen the focus on women’s health throughout all stages of life.

Let’s look then at these mighty hormones and their effects inside our heads, from the ups and downs of pregnancy to the crash that follows menopause.

HORMONES FROM THE NECK UP

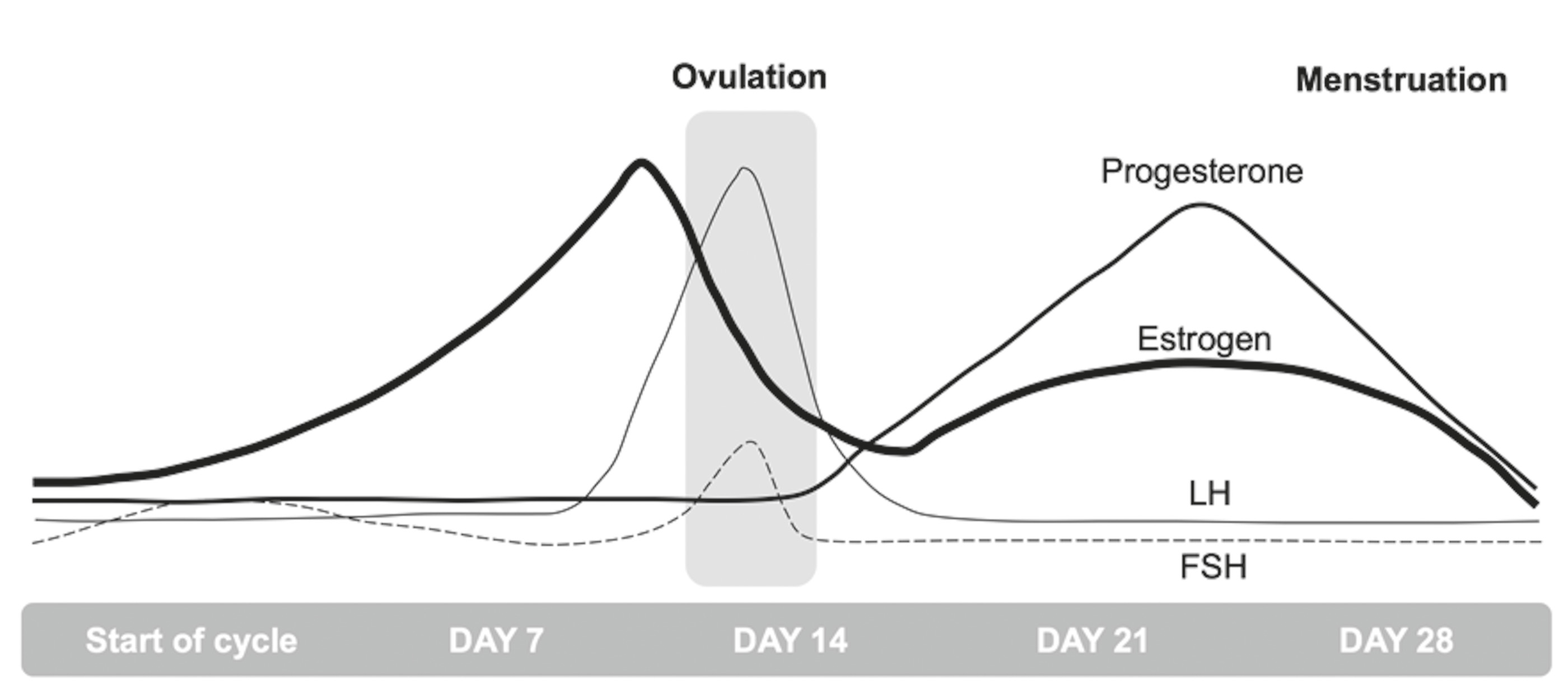

So far, we’ve mostly talked about estrogen, but three other key hormones also deeply impact the female brain and body as they fluctuate throughout the menstrual cycle. These are progesterone, the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and the luteinizing hormone (LH).

As shown in figure 2, after the last day of a woman’s period, her body starts preparing for the next ovulation. FSH stimulates the ovaries to produce a mature egg. This maturing process produces estrogen (mostly estradiol). During the menstrual cycle, estrogen is high when progesterone is low, and vice versa. Specifically, in the first half of the menstrual cycle, estrogen is nice and high, busy making us feel “sexy” while at the same time promoting the growth of the uterine lining so as to provide the egg with the support it needs to host a baby. Progesterone sits in the back, waiting for the happy news.

During ovulation, the mature egg is released into one of the fallopian tubes and travels to the uterus. If it comes in contact with sperm and is fertilized, a woman is effectively pregnant. But if the egg is not fertilized, another hormone, LH, peaks and then initiates the so-called luteal phase. Estrogen drops and naturally withdraws to give way to progesterone, which proceeds to dismantle estrogen’s work, breaking down the uterine lining in the process. The thick lining and blood that were built up during the follicular phase will then be able to leave the body, and voilà, we’re menstruating, and a new cycle begins.

FIGURE 2. SEX HORMONES DURING THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Because of estrogen’s energizing, mood-boosting effects in the brain, most women feel happier and generally more active during the first part of the cycle. During ovulation (in the middle of the cycle), as estrogen makes way for progesterone, many women feel tense or edgy at first, and much calmer afterward. That’s because progesterone is a soothing and sleep-promoting hormone that has a multitude of effects throughout the body. Many of these effects can be attributed to its ability to counterbalance the action of estrogen, since these two hormones work in tandem, complementing and regulating each other. Imagine estrogen and progesterone sitting on either end of a seesaw, shifting rhythmically up and down over the course of your menstrual cycle. After age thirty-five, though, the amount of progesterone you make starts varying from month to month. When progesterone goes down, estrogen will rise on the seesaw. The problem is when these changes are so pronounced that progesterone ends up slamming into the ground. When progesterone levels are low or out of balance—for example, for women who suffer from PMS or, in general, during perimenopause—we tend to experience insomnia, anxiety, migraines, miserable periods, irritability, and even rage. And since it’s also a natural diuretic, we get bloated, too.

While not a “female” hormone per se, testosterone is also involved. Men have approximately ten times more testosterone than women, though women produce some testosterone too. This hormone helps regulate sex drive while modulating bone and muscle mass and fat distribution. When testosterone levels are particularly low, women experience not only a loss of libido but also weight gain and low energy. The opposite can happen as well. For instance, women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), a common cause of infertility, produce a high level of testosterone that can cause menopause-like symptoms including irregular periods, difficulty sleeping, and insulin resistance.

The female brain is in continuous contact with all of our hormones and with our ovaries thanks to a highly specialized network called the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, or HPG axis (figure 3). The network owes its name to two brain structures that are directly involved in the reproductive cycle: the hypothalamus, located deep inside the brain, and a tiny gland called the pituitary gland sitting just below the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is in charge of stimulating estrogen and progesterone production in the ovaries, while the pituitary gland secretes both FSH and LH. This interplay of hormones circulating up and down the HPG axis is regulated by a feedback mechanism that reports to the brain in real time, day after day, throughout our lives as women.

FIGURE 3. THE FEMALE NEUROENDOCRINE SYSTEM

The hypothalamus is on talking terms not just with the ovaries, but with many parts of the brain, too. These include especially the memory and emotional centers of the brain (the hippocampus and amygdala), as well as another region called the posterior cingulate cortex, responsible for storing memories of all the things you’ve done and the places you’ve been. The largest part of the brain, the frontal cortex involved in attention, language, and reasoning, is also tightly connected. And if you remember from chapter 1, these regions are all the more interconnected in women than in men.

Additionally, the HPG axis is in touch with two structures located in the most primitive part of the brain, or the brain stem. These are the raphe nucleus, our main source of mood-regulating serotonin; and the locus coeruleus, in charge of the fight-or-flight response. All these regions are part of the brain’s estrogen network and quickly respond to variations in estrogen levels, which also helps clarify the extent to which our hormones are involved in most aspects of our cognitive and emotional life.

All is well within this intricate system as long as our hormones support and regulate one another in harmony. However, two major events have the power to disrupt this fine-tuned balance: pregnancy, with the subsequent arrival of a baby, and its nemesis, the onset of menopause and the end of our reproductive life. While these events are two entirely different stories, both can have a strong impact on our brains, and on our mental capacities in turn.

THE PREGNANT BRAIN: FLIP OR FLOP?

As many of us know only too well from personal experience, creating a human being from scratch is no small feat. Pregnancy heralds a period of remarkable change in a woman’s body as we literally become the “starter home” to another person. While we have the profound pleasure of hearing a new heartbeat and sensing the first kicks and wriggles inside us, other things are occurring that don’t inspire quite the same glee.

One of the hallmarks of pregnancy is an enormous surge in our sex hormones, with estrogen and progesterone ballooning to fifteen to forty times over their usual levels in an effort to prepare the body to carry a child. Our bellies are growing, ankles are swelling, backs are aching. At the same time, surges of oxytocin (aka the love hormone) cue the uterus for its upcoming contractions, while getting the breasts ready to produce milk. But the changes don’t stop there. Women frequently report that bringing a new life into the world can also have a major impact on their brains. At some point during pregnancy, many women will ask themselves, “Is this little bundle of joy stealing my body? My life? And oh no, even my brain?” “Pregnancy brain” refers to the feeling of forgetfulness, inattention, and mental fogginess that sometimes accompanies pregnancy, just as “baby brain” refers to similar symptoms that occur once the baby is born. Can our hormones be hijacking our brains somehow?

The only other time that our bodies produce comparable levels of sex hormones is during puberty. Research has shown that this stage of life not only provokes hormonal changes in the body but also spurs dramatic structural and organizational changes in the brain. From prenatal development through adolescence, both boys’ and girls’ brains are busy growing neurons at light speed. A baby’s brain contains more than 100 billion neurons, constituting about as many nerve cells as there are stars in the Milky Way. During a child’s early years, synapses (the connections between neurons) further develop at the explosive rate of up to 2 million per second. As the child grows, many of these synapses are, however, discarded via a process of elimination called pruning. By early adolescence, about half of the original synapses are shed as a child’s brain sculpts itself into its more mature form.

Thanks to new research, we now know that a similar “remodeling” takes place deep inside the pregnant brain. A seminal study performing brain scans on women before and after pregnancy found significant modifications in the areas of the brain associated with processing and responding to social signals. It’s as if our brains were making space for new information to be gathered after a baby’s birth. Interestingly, these striking changes, which were still present up to two years after their children’s birth, were in the same brain regions that light up across our screens when new moms look at photos of their infants, and correspond directly to the degree of maternal attachment. These changes were so consistent that a computer algorithm based on this data could successfully distinguish pregnant women from a control group of women without children.

It is believed that this brain’s makeover, so to speak, is associated with a maturation and specialization process that allows women to become more focused and attuned to their baby’s needs. Basically, experiencing forgetfulness or brain fog during pregnancy doesn’t mean you’re losing your mind after all. You’re actually in the process of building a whole new one! Your brain is busy refurbishing the new spaces and pathways that will allow you to become even more responsive to the myriad demands of motherhood. It’s precisely the intensity of the remodeling going on that can lead us to notice shifts in memory and attention, which, all things considered, is no small wonder.

Is “Momnesia” Real?

Baby brain, or the cleverly coined “momnesia,” is a much-noted phenomenon. Momnesia, however endearing a term, can be broadly described as “the state of mind where you are so overwhelmed with things to do, noise, and the needs of kids that you cannot remember one thing from one moment to the next.” It refers to the rather disconcerting feeling of walking into a room to grab something, only to forget what it was you came for. Or leaving curling irons plugged in, or remembering at the last minute that a playdate or soccer practice is scheduled. Once I pushed an empty stroller all the way to the market because I had somehow forgotten that my daughter was at the park with the nanny. The examples are endless. This new “ritual” can become downright infuriating when performed a good many times a day. Lost keys, forgotten appointments, and misplaced bags are all common symptoms.

While not all studies agree, some evidence indicates that women can experience measurable changes in a variety of cognitive skills, memory first and foremost, both during and after pregnancy. For example, a cumulative analysis of fourteen different studies discovered that new moms generally experience reduced performance on memory tests that place a high demand on free recall and working memory. Free recall refers to the ability to remember items on a list, while working memory is your ability to keep many things in mind at the same time, similar to the RAM on a computer.

It is worth mentioning that memory difficulties were more pronounced depending on the number of children a woman had—a factor that didn’t seem to have any impact on fathers . . . Whether these difficulties derive from the onslaught of multitasking that surrounds us as new moms or are due to shifts in our brain chemistry is a good question—one to which we can enthusiastically answer: both!

Nonetheless, even though most mothers may not feel as sharp as they used to, their brain’s capacity is definitely unaltered. Your IQ hasn’t changed a bit—but your priorities have. For example, the average mom tends to accumulate up to seven hundred hours of sleep debt (700!) in the first year with the baby, draining the brain of much of its latent power as it dedicates itself to caring for a child 24/7. Let’s face it: when any one of us is getting but a fraction of our usual amount of sleep while at the same time juggling both the basic and the vital new to-dos of the day, even a top-notch noodle is doomed to suffer. A combination of sleep deprivation, shifting hormonal levels, and our newfound roles all combine in challenging us to keep it together.

Given the herculean tasks that confront motherhood at any stage, my best advice is to have respect for and awareness of this, and be gentle with yourself. Ask for help whenever possible to simplify any other areas of your life that can withstand it. Just as you think you’ve seen it all, life is about to get even more “interesting,” however wonderfully so. As you tackle this very female version of Mission Impossible, it’s a good time to reach for a game plan that’s customized for you, one that just might make it possible after all.

A Heartfelt Arrival

Most of the changes that come with pregnancy, like the baby bump, exhaustion, and quirky food cravings, are healthy, temporary, and harmless. But two medical complications that may develop as a result of pregnancy can have long-lasting implications for the health of your heart—and therefore your brain—and need to be taken very seriously. These are

-

high blood pressure during pregnancy (preeclampsia)

-

gestational diabetes

Both conditions differ from “regular” high blood pressure and diabetes because each of these pregnancy-related conditions typically goes away once the baby is born. However, research suggests that they may signal a woman’s predisposition to develop heart disease in the future, or more specifically, around menopause. For example, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children looked at pregnancies in more than 3,400 women who were followed for nearly twenty years. Once they reached age fifty, those women who developed preeclampsia during their pregnancy had a 31 percent higher chance for heart disease than women who didn’t. Those who developed gestational diabetes had a 26 percent higher risk of heart issues after menopause. Additionally, women with preeclampsia were more likely to deliver prematurely and give birth to underweight babies, while those with gestational diabetes were more likely to deliver overweight babies.

Luckily, preventative interventions can ensure that both mom and baby are healthy throughout pregnancy and for the years to come. These problems can often be avoided entirely by keeping an eye on healthy weight gain during pregnancy, exercising gently but regularly, and adopting a healthy diet before and during pregnancy. That said, women who are meticulous about all these factors can still develop preeclampsia or gestational diabetes. If you develop (or developed) either condition during pregnancy, it’s a good idea to talk with your doctor about tracking your blood pressure, blood sugar, and insulin levels as you get older. Keeping cardiac risk factors such as weight and cholesterol levels under control is also important, as described in part 2.

Postpartum Depression: Sadness as the Stork Flies Home

While the birth of a baby can trigger a jumble of powerful emotions, ranging from excitement and joy to fear and anxiety, it can also spur something one might not expect: depression. Recent research indicates that as many as 70 to 80 percent of all new moms experience some depressive symptoms within the first two weeks of delivery. These so-called baby blues, which commonly include mood swings, crying spells, anxiety, and difficulty sleeping, are primarily attributed to the intense hormonal changes that come with childbirth.

However, about one in every ten new moms will experience something more serious, finding herself struggling with a deep sadness, steeper anxieties, and even the loss of a sense of self-worth for several weeks or more. This condition is called postpartum depression (PPD). If left untreated, it can severely affect a woman’s ability to get through her daily routine. Another possible though unlikely condition is a mood disorder called postpartum psychosis. This extremely rare condition may include hallucinations, paranoia, and, rarer still, thoughts of harming oneself or others.

Both PPD and postpartum psychosis have long carried a social stigma. Instead of supporting and helping women heal from such trauma, society has historically turned against them, by categorizing them as “mad” and even going so far as to accuse them of being witches or victims of witchcraft. Quite remarkably, it wasn’t until the late date of 1994 that the psychiatric community recognized PPD as an actual medical condition. It’s no surprise, then, that women have felt apprehensive about discussing it publicly. In 2005, Brooke Shields lent her celebrity presence to PPD by sharing her experience battling the condition that women had silently suffered from throughout history. Now, over a decade later, PPD has become a household term and women are often given the assistance they need to progress through the depression and return to well-being. Pregnant women are routinely screened for it by their ob-gyns, and later by their pediatricians during infant checkups.

Suffering from PPD isn’t in any way, shape, or form reflective of a character flaw or weakness. Quite the contrary. It is a physiological complication of giving birth, one that takes great strength of character to manage and overcome. If being a new mom has brought you feelings of anxiety or depression that seem more extreme than those that come from the challenges of the moment, what you’re experiencing could be symptomatic of a recognized medical problem.

Whether you’re experiencing the symptoms of PPD or reacting to the steep adaptation that motherhood requires, the best thing you can do for your baby, your family, and yourself is to check in with your doctor and tell it like it is. Rest assured, these conditions can now be effectively treated. The symptoms are more often than not the result of a medical problem with clear-cut solutions. Just last year the FDA approved Zulresso (brexanolone) as the first drug designed to specifically treat PPD. Hopefully, more therapeutic options will soon become available. The symptoms of PPD often respond best when treatment is started right away, so when in doubt, reach out for help sooner rather than later to be sure you get whatever assistance you need.

To all new moms, whether you experience shades of PPD, moodiness, or just sheer exhaustion, I hear you. The adjustment to motherhood can be very stressful as you learn to navigate your new role, balancing care for yourself and an infant, not to mention other children and family members, too. All of this inevitably adds up and takes its toll. I promise you, this traffic jam of demands doesn’t last forever. But while you’re knee-deep in them, the lifestyle changes and select supplements described in part 3 of this book can help you feel better and manage the symptoms as you go.

THE BIG M

Now let’s move on to the other end of our reproductive years, where we encounter the “Big M,” aka “the Change,” or even “That Time.” Whatever name it goes by, all women go through menopause—the time in a woman’s life when her hormones wane as she loses her ability to bear children. Some women eagerly anticipate this moment, feeling liberated from pregnancy worries, premenstrual mood swings, and the monthly routine of tampons and cramps. For others, the thought of menopause comes with a prickly mix of emotions as they contemplate a distinct departure from their youth and attempt to broach the subject of their aging instead, struggling with what it all means in regard to their womanhood.

Whichever way you look at it, menopause signals the opening of a thus far historically unglorified chapter in a woman’s journey, one that has the potential to take us on a wild roller-coaster ride beginning as early as our thirties and lasting easily a decade or more. From hot flashes and weepiness to insomnia and forgetfulness, menopause can be deeply disturbing for many. While some women sail through, barely noticing the shift, many others are plagued by hot flashes, aching joints, sore breasts, or a reduced sex drive—and an increased risk of developing a number of medical conditions that can negatively affect both the body and the brain.

In spite of the steep physical and emotional hurdles that often accompany menopause, speaking openly about it remains taboo. Unfortunately, as a result, some women feel as if they are alone in experiencing such changes, and many remain reluctant to openly discuss their symptoms. Often, when they do get up the courage to broach the subject, both family and doctors alike can be nonplussed or dismissive. Some women don’t even realize that what they’re experiencing has anything to do with menopause at all. Many are embarrassed to be suffering such symptoms in the first place and strive to hide them. In our youth-obsessed culture, there is something about the word menopause that signals negative associations with age, as if age is nothing more than a sign of deterioration and shame—rather than a marker of deeper wisdom, accomplishment, and perspective. As a result, menopause is an issue that is often avoided rather than confronted, thereby turning away curiosity, understanding, and support.

However, things are changing as more and more women open up about their experience in more overt, confident ways. Actress Kim Cattrall, better known as Samantha in Sex and the City, has given voice to many women’s experience by describing menopause this way: “Literally one moment you’re fine, and then another, you feel like you’re in a vat of boiling water, and you feel like the rug has been pulled out from underneath you.” X-Files actress Gillian Anderson said she felt her life was falling apart and that she could handle nothing for years before finally getting to the other side of menopause. Whoopi Goldberg was candid enough to discuss the loss of sex drive many women experience as hormones falter. Tales abound of sudden and embarrassing sweating in public places, lack of sleep, forgetfulness, and in some cases, even an acute sense of despondency.

In 2018, many of us were shocked at the news of the suicide of fifty-five-year-old Kate Spade, the celebrated designer. Only a few years before, fifty-year-old fellow fashion designer L’Wren Scott suffered a similar fate. One can’t help but wonder if hormonal changes may have somehow played into their tragic demise.

Sadly, we will never know, but what we do know is that suicide rates for middle-aged women have gone up nearly 60 percent in recent years. Clearly, something is afoot that can’t be explained away as midlife crises or random misfortune. Although assessing these statistics requires a broad-scope look at the many complex and oftentimes hidden challenges women are currently confronted with in our society, this book begins to attend to this essential aspect of women’s health, one that has thus far eluded our attention.

In the United States alone, approximately six thousand women are reaching menopause each day. Many are caught completely off guard. Thanks to how genuinely uninformed we are about menopause, many women remain baffled by what they experience, often feeling betrayed by their own bodies—not to mention by their doctors. The news that up to 80 percent of all women going through menopause have the potential to develop actual neurological symptoms (and an increased risk of dementia) raises the stakes even further.

However, it’s not only those experiencing natural menopause who are at risk for the potential consequences of estrogen loss. Women are plunged into menopause daily because of surgery or cancer treatments as well. Here in the United States, about one in every eight women undergoes an oophorectomy (the surgical removal of the ovaries) prior to natural menopause. Similar rates are reported in Europe, while in China more than 250,000 hysterectomies (the surgical removal of the uterus, oftentimes along with the ovaries) are performed each year. Having had her ovaries removed may have saved Angelina Jolie’s life, but this choice also meant her body would be subject to premature menopause.

Scientists have long known that, unfortunately, when a woman’s ovaries (or even just one) are removed prior to menopause, she has a greater risk of memory decline and dementia—up to 70 percent higher in some cases. That’s on top of a likewise increased risk of anxiety and depression—another issue that remains largely unaddressed in medical practice. Most women are not aware of this at all. To be fair, most doctors aren’t either. But please take heart! As discussed in part 3, new research indicates that hormonal therapy after surgery appears to reverse those risks, at least for some women, suggesting that there may very well be a critical window for this therapy and subsequently for protecting one’s brain from any adverse effects. Other solutions are also available, which we’ll discuss in the next chapters.

Are Menopause Myths Holding You Back?

All this new research is forcing us to come to grips with the fact that almost everything we’ve heard about menopause so far, be it information handed from mother to daughter or from doctor to medical student, has been wrong, or at least misguided. Many patients have told me that one of their greatest challenges was finding information they could readily consume, and most important, trust. This chapter’s goal is therefore to help women understand what’s happening to their brains, as well as to their bodies, as we take control of our changing health-care needs.

One of the issues I’ve encountered in my own research is just how much misinformation about menopause is out there, making it hard to separate myth from fact. Before we start discussing solutions, it’s urgent and helpful to bust a few common misconceptions about what menopause is and isn’t.

MYTH #1: MENOPAUSE HAPPENS WHEN YOU’RE OLD.

Fact: The vast majority of women develop menopause in their forties and early fifties.

All women, somewhere in the neighborhood of forty-two to fifty-eight years old, go through menopause. In most industrialized countries, the average woman becomes menopausal at age fifty-one. Some women experience menopause earlier than usual, before age forty-two, which is sometimes referred to as “premature menopause.” It can occur even earlier in women who have had their ovaries surgically removed, either alone or along with the uterus (hysterectomy), or whose ovaries stop working for other reasons such as cysts or reactions to cancer-fighting medications that strip the body of estrogen.

MYTH #2: YOUR PERIOD WILL JUST SUDDENLY STOP ONE DAY.

Fact: Your body takes years to go through menopause.

Many women believe that one day you suddenly stop having your period and that’s that. Although there are some women who report barely noticing that their periods have disappeared, most only wish it were that simple. Menopause is defined as the final menstrual period, which is confirmed after a woman has missed her period for twelve consecutive months. But the hormonal changes leading up to menopause occur over a fairly long period of time, taking one to eight years for the ovaries to officially retire, ending your cycle once and for all.

When a woman’s body is in the process of transitioning toward menopause, menstrual periods typically become less frequent and more irregular, and hormonal levels begin to fluctuate. This stage is referred to as perimenopause. Although a woman still experiences her periods during perimenopause, both the length of the menstrual cycle and the levels of circulating sex hormones become highly variable. On top of your period being all over the menstrual map, this can make for physical and emotional changes as well. Since periods can become less frequent during this time and one gets more used to missing them, in the end, it is often hard to know when they have actually stopped for good. This is of course much different for women who have their ovaries surgically removed, who, from one day to the next, go from having a regular cycle to finding themselves smack in the middle of menopause.

MYTH #3. AFTER MENOPAUSE, A WOMAN’S BODY STOPS MAKING HORMONES.

Fact: Menopausal women continue to produce hormones. But different ones.

Although hormone production significantly decreases after menopause, it doesn’t ever stop entirely. For example, a little bit of estrogen is still being made. It is important to clarify that, although we tend to refer to estrogen as if it were a single hormone, in reality, there are three forms, or subtypes: estradiol, estriol, and estrone. Throughout this book, I use the term estrogen to refer to the combined effects of all three types, unless it’s important to discuss each type specifically.

When doctors talk about “estrogen,” they are usually referring to estradiol, which is the strongest of the three. Estradiol is produced by the ovaries during our reproductive years, and its levels are markedly reduced after menopause. Estriol is produced mostly during pregnancy. Estrone is the most prevalent estrogen in post-menopausal women. It is made by adipose fat rather than by the ovaries. So after menopause, we still have some estrogen going, mostly in the form of estrone. However, estrone is not nearly as potent as estradiol—hence the various symptoms and imbalances.

MYTH #4. MENOPAUSE AFFECTS ALL WOMEN THE SAME WAY.

Fact: Women experience menopause very differently.

All women go through menopause, but every woman’s experience of menopause is different. Both the type and the extent of symptoms are extremely varied from woman to woman. Some women report no physical changes aside from irregular menstrual periods that stop when menopause is reached. Other women experience a multitude of symptoms from everyday hot flashes and night sweats to more extreme symptoms such as pain and even electric shock sensations.

An effective diagnostic approach to menopause has been complicated by yet another commonplace factor of Western medicine—the reliance on a one-size-fits-all approach, which is the continuation of the misunderstanding and marginalization of women’s health that has existed since doctors first started treating women. Fortunately, there is an increasing understanding that each woman is unique and may experience menopause differently from other women—and therefore needs individualized treatments.

MYTH #5. MENOPAUSE AFFECTS WOMEN ONLY PHYSICALLY.

Fact: Menopausal women experience both physical and psychological shifts.

The reason women start losing estrogen in their forties and fifties (and in some cases even earlier) is that our neuroendocrine system is in transition. As the term indicates, this means that the brain (nervous system = neuro) and reproductive organs (endocrine system = hormones) are both involved and, therefore, equally affected. As mentioned before, many of the signature symptoms of menopause begin in the brain.

However, if talking about menopause is still taboo, its effect on mental well-being is totally not dinner conversation material. The result is that many women are terrified of going crazy but don’t know whom to speak to about their concerns. I am here to tell you: You are not crazy. Your brain is changing, and so are your physical and emotional health. If you are experiencing these changes, know that they are a perfectly normal reaction to what’s going on inside your brain and body. Unpleasant, for sure; daunting, even. But there is nothing wrong with you. Thankfully, there are ways to traverse this period of your life healthily and confidently thanks to a new understanding of and respect for this transition, one that this book is here to help you support and manage.

MYTH #6. WE HAVE NO CONTROL OVER MENOPAUSE.

Fact: While there are some facts of life we can’t change, others are well within our control.

There are a number of factors that affect a woman’s experience of menopause. Some of them are outside our control, whereas we can actually intervene with others. One factor you cannot change is that menopause is in part genetically linked, so you’re quite likely to experience your menopause around the age your mother experienced hers. This isn’t always true, as some women do deviate from this path. If your mother reached menopause at forty, but her sisters and your grandmother all experienced it around the age of fifty, it’s hard to tell whether you’ll follow her path or theirs. But more often than not, if most of the women in your family, your mother included, reached menopause early, late, or somewhere in between, you can eye your calendar with some degree of confidence.

The experience of menopause is also somewhat similar between mother and daughter. If your mom didn’t have symptoms of menopause, chances are you won’t either. If, instead, she did experience various symptoms, it is possible that you may, too—unless you actively take precautions to avoid the behaviors known to trigger these symptoms.

There are quite a few non-genetic factors that can accelerate and accentuate both the timing and degree of menopausal symptoms, while others may slow and steady the process instead. Our goal, of course, is to minimize the former scenario while maximizing the latter! For example, no lifestyle factor does more damage to your ovaries than smoking. If you smoke and your mother didn’t, you’ll probably reach menopause earlier than she did. On the other hand, if she smoked and you don’t, you may experience menopause later than she did. Other lifestyle factors that influence the experience of menopause include your diet, exercise, sleep quality, stress levels, and even various medications. We will talk about all of these in part 3.

The Brain Symptoms of Menopause

Now that we have clarified what menopause is and isn’t, let’s take a closer look at the specific effects of menopausal changes on our brains. For those who still insist on using menopause as a cute punch line to a sexist joke (likely told by someone who has never experienced a night sweat), it’s important to clarify that the menopausal ebb in estrogen doesn’t just leave us fighting hot flashes, but also has us courting more serious issues such as a weakened memory and an increased risk of cognitive decline. The most common “brain symptoms” of menopause are reviewed below. Many, if not all, of these symptoms can be managed and often wholly reversed by following the program outlined in the chapters to come. Post-menopausal women will also greatly benefit from the lifestyle and medical decisions provided, all of them proven to protect and invigorate the mind at any age.

BRAIN FOG AND MEMORY LAPSES

It’s quite common for women over forty to complain of “brain fog,” exhaustion, forgetfulness, or difficulty concentrating. The memory lapses many women notice are real, and they can begin at a relatively young age, only to worsen as our hormone levels drop. Studies have shown that up to 60 percent of women report reduced focus and mental clarity as they go through perimenopause. Menopause-related cognitive changes happen to women in their forties and fifties, if not earlier—women in the prime of life who suddenly have the rug pulled out from under them. For some women, cognitive performance recuperates years into menopause. For many others, it does not, and may actually further deteriorate or even turn into a dementia diagnosis in later years.

HOT FLASHES AND NIGHT SWEATS

As any woman can attest to, there’s nothing really “hot” about hot flashes. Hot flashes, along with their nocturnal counterpart, the night sweat, are a phenomenon called vasodilation—an indicator that your brain is undergoing a global warming crisis. The sweats are indeed a sign of the brain not doing its job correctly, in this case by failing to properly regulate body temperature. During a hot flash, some women experience an unannounced and sudden onslaught of heat so intense that it causes their face and neck to feel flushed and overheated; sometimes this is just as obvious on the outside as it feels inside. Other women go hot and then chilly instead. The hot flash can sometimes cause an irregular heartbeat or palpitations, and even headaches, shivers, and dizziness, which, all things considered, is really no picnic.

A typical hot flash can last anywhere from thirty seconds to ten minutes, although some can last more than an hour. The severity of the hot flash also differs among women. On average, a lucky 3 percent of women skate through menopause without ever breaking a sweat. Another 17 percent have mild, broadly tolerable hot flashes. But the vast majority of women suffer from hot flashes that can be severe and bring a considerable amount of stress to their lives.

Until recently, experts believed these sudden and intense waves of heat were a so-called temporary problem, affecting a woman for no longer than three to five years after her final menstrual period (which by anyone’s standards strains at the definition of “temporary”). Instead, for many women, hot flashes continue many years post-menopause. This is particularly the case for current or former smokers and women who tend to be overweight, but also for those who are stressed, depressed, or anxious—which gives us even more of a reason to attend to all these problems. Seriously, if men had hot flashes, we’d have found a solution a long time ago!

Moreover, while most people persist in thinking of hot flashes as solely a quality-of-life issue, recent studies have called that theory into question too. It turns out that women who experience hot flashes earlier in life tend to have poorer endothelial function, a sign that their arteries are losing their ability to flex and relax, which can increase the risk for future heart disease. Since current diagnostic tests are not always accurate enough to predict heart disease for younger women, hot flashes may actually serve a positive purpose after all, acting as a red flag in helping to identify younger women who could benefit from early checkups. In the name of toasting a glass half full, we’ll consider this a rather uncomfortable version of a silver lining.

DISTURBED SLEEP

On top of losing its grip over our internal temperature, our brain also falters at regulating our sleep-wake cycles, which points to hormonal declines as the trigger for many women’s sleep issues. Insomnia is a prevalent symptom of menopause, frequently associated with night sweats, depression, and cognitive disturbances. Of course, if a woman is not sleeping well, her mood and eventually her mental equilibrium will no doubt be affected, too. Further, sleep is essential in the formation of memories and in cleaning out amyloid deposits that can lead to Alzheimer’s, which makes resting our busy minds crucial for the long run.

LOW MOOD AND DEPRESSION

Hormonal declines affect mood as well, oftentimes leading to depressive symptoms. Happy highs that are prone to turning into teary-eyed lows, or cheerful times followed by a string of crabby days, can challenge even the most even-keeled among us. This is a tricky area, however, since depressive symptoms caused by menopause can be difficult to distinguish from symptoms of depression due to other causes.

Aside from pregnancy-related depression, these include major depression, which probably has a stronger genetic component, and “situational” depression, which occurs after a particularly traumatic event, like a death in the family or losing your job. It’s important to figure out which form of depression one is suffering from, because treatment can be very different depending on the cause. Far too often a woman will go to her doctor to discuss menopause and leave with a prescription for antidepressants. While antidepressants are needed in some cases, other strategies can and should be put in place to specifically deal with hormonal depression and its root causes.

INCREASED STRESS

Menopause can definitely cause stress, and stress can make all the brain symptoms of menopause a lot worse in turn. Stress itself originates in the brain, and our resilience to stress is largely in our hormones’ hands. Let’s back up and take a closer look at that. All sex hormones are produced through a series of sequential steps that start with cholesterol, that special kind of fat your doctor routinely measures in your blood. The body uses cholesterol to make a hormone called pregnenolone, which is also known as the mother of all sex hormones. Pregnenolone is in fact converted into progesterone, and progesterone can then be used to make estrogen or testosterone. This process tends to sing along without skipping a beat . . . as long as you are not stressed out. When you’re under stress, another hormone steals the show. Enter cortisol, the number one stress hormone.

Here’s the story. Your adrenal glands use pregnenolone, too, but to make cortisol. When you’re under acute but temporary stress (e.g., you have an exam coming up soon, or there’s a medical emergency that resolves quickly), your body will reroute some of its pregnenolone to increase cortisol production. Once the stressor is gone, cortisol production slows down and your body resumes its usual estrogen and progesterone production. But when you’re under chronic stress, your cortisol levels skyrocket and remain high for prolonged periods of time. Your body has no choice but to keep making cortisol by stealing pregnenolone away from your sex hormones.

Several things happen to you then: your pregnenolone goes down (making you feel irritable), your progesterone plummets (keeping you awake at night), your estrogen subsides (giving you hot flashes), and your thyroid intervenes to slow down your metabolism (so now you are exhausted too). If you thought you were having problems before, now you’re really in the soup. In the short term, too much stress leaves you drained, unhappy, and perpetually overwhelmed. In the long term, it can also lead to more serious problems like depression, heart disease, and an increased risk of dementia. Nobody wants that. It’s important to always take steps to avoid or reduce stress. Your body and brain will thank you for it later!

LOW SEX DRIVE

As the hormones that have been regulating the reproductive cycle, libido, and mood are ebbing, these lower levels can have a negative effect on women’s sex life as well. Loss of desire is common in the years before and after menopause, peaking anywhere between the ages of thirty-five and sixty-four. Although these changes do not happen to all women, declining female hormones often lead to vaginal dryness, painful intercourse, difficulty becoming aroused, and an overall loss of sexual desire. If that weren’t enough, hot flashes can make a woman feel unsure of herself and less desirable, carrying a huge impact on every aspect of her life, relationships included.

From a biological perspective, the actual loss of sexual desire is once again taking place inside our heads. The euphoric and pleasurable experience of sex stems primarily from the limbic system, that part of the brain that is also responsible for memory, affection, and mood. Therapies designed to support brain health and hormonal production, whether by means of counseling, medications, or lifestyle interventions, are therefore just as helpful to boost libido and stamina.

In the end, for many women, menopause is no joking matter. Over the last several years I have spoken to women in various states of emotional distress due to their menopausal symptoms, hearing the way that they have been treated by their doctors, colleagues, and even their own partners. I hear similar stories every day of every week, and I know that for every woman I work with, there are thousands of others out there having similar experiences. Surely it is time we started demanding solutions! And by solutions I mean evidence-backed recommendations, not some internet blog telling us to buy more supplements.

In parts 2 and 3 of this book, I will share a number of testing procedures that are indispensable to digging out the root causes of menopausal symptoms as well as other medical conditions known to affect our brains—and many recommendations to alleviate, and whenever possible, reverse the symptoms. Before we proceed, I want to draw your attention to a particular question I asked myself when I first started researching menopause.

Why Do We Have to Go Through This at All?

For anyone with ovaries, menopause is a fact of life, one we tend to take for granted. But menopause is a long-standing biological riddle, one that scientists haven’t managed to fully explain. In fact, there are only two species on the entire planet that outlive their fertility: women . . . and whales!

When we look at this within an evolutionary framework, we could ask why we continue to live beyond the time we’re fertile, while females of other species die once they lose the ability to reproduce. It would seem that if females continued to reproduce for the duration of their lifetimes, that would only maximize the passing on of their genes. So why are we built to do otherwise?

New research on whales—killer whales, no less—provides a clue: perhaps menopause is nature’s way of avoiding a mother-daughter reproductive conflict. Killer whale societies are matriarchal, and sons and daughters live out their lifetimes with their mothers rather than their fathers. In addition, mothers stay close by to help raise their grandchildren. In this scenario, it is indeed advantageous for the mothers to lose their fertility, thereby eliminating any reproductive competition with their daughters and daughters-in-law.

This societal pattern in killer whales is similar to that of ancient humans. While living in hunter-gatherer societies, the men went hunting while the women stayed behind to raise the children. It is possible that avoiding reproductive competition might also underpin human menopause. Since women today are living far longer than their female ancestors, the time has come to roll up our sleeves and figure out how we can protect and invigorate our minds, even as our estrogens ebb.

Menopause: A Wake-Up Call

Until fairly recently, menopause was written off as the unnatural outcome of women’s increased life expectancy, the unfortunate upshot of their living well beyond what nature intended. Subsequently, medicine met it with little more than a shrug. In recent years though, research has made tremendous progress in demonstrating that menopause is not only a pivotal aspect of women’s health, deserving of proper attention, but also a wellspring of information destined to inform the future of women’s health care.

When menopausal symptoms are attended to with adequate research and customized care, the host of potential issues that often accompany this hormonal shift can often be avoided. When it comes to a woman’s cognitive health, menopause remains the only factor known to increase Alzheimer’s risk in women and women alone, putting us at a distinct disadvantage based solely on gender. Between the way this hormonal juggernaut can produce symptoms that constrain women’s quality of life for decades, and the fact that it puts us at risk for one of the most devastating diseases known to humankind, it warrants our fullest attention, and pronto.

Instead of keeping the blinders on when faced with the challenges of menopause, perhaps it’s the wake-up call we’ve been waiting for, prompting us to take action. The choices we women make during this transition can have profound effects on our future health. In order to make the right choices, you want to identify your risk factors and predispositions so that you can personalize your plan with what will work best for you. I will assist you with this starting in the next chapter.