Egypt Today

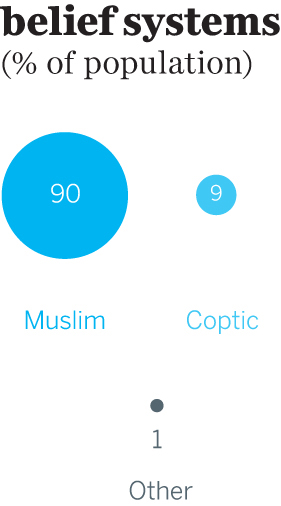

Egypt was long seen as the land of eternity, where nothing ever changed. That image has been shattered by political events since 2011, but some things remain: Egypt’s location, its huge population and its control of the Suez Canal ensure that it is still a major player in the region. Even with the turmoil following the downfall of two presidents in as many years, it still enjoys great prestige in diplomacy, the arts and as a moderate Islamic country.

Best on Film

The Square (2013) A documentary that looks at the turmoil in Egypt from 2011–13. It won three Emmys and was nominated for an Oscar.

The Yacoubian Building (2006) Blockbuster Egyptian movie adapted from Alaa Al Aswany’s novel, portraying the stories of the residents of one block of flats in downtown Cairo.

In Search of Oil and Sand (2012) Egyptian historian Mahmoud Sabet’s brilliant documentary uses home-movie footage to show the downfall of King Farouk.

Best in Print

Taxi (Khaled Alkhamissi; 2006) Best-selling novel, and now also play, of 58 fictional monologues of Cairo taxi drivers.

The City Always Wins (Omar Robert Hamilton; 2017) Dazzling first novel set in Cairo during the 2011 uprising.

The Cairo Trilogy (Naguib Mahfouz; 1956–57) By the Nobel prizewinner, this epic trilogy tells the story of three generations of a Cairene family in the early 20th century.

The Yacoubian Building (Alaa Al Aswany; 2007) Best-selling exposé of Egyptian society during the 1990s.

After Mubarak

When interim president Adly Mansour made way for the newly elected President Sisi in June 2014, it was the first time an incumbent Egyptian president had ever relinquished power. Sisi’s rule so far, though, has struggled to address Egypt’s political and economic instability. There have been grand gestures – most notable being an extra channel for the Suez Canal, pushed through quickly and at vast expense – and even grander statements, including building a new capital city. But behind the headlines, the old problems fester. Mass poverty, poor education and healthcare, growing sectarian conflict and economic turmoil are all, to some degree, interconnected, and none of them can be resolved easily. Steps in 2016 to devalue the Egyptian pound and slash subsidies to secure a US$12 billion loan from the IMF and stimulate the economy have, in the short term, resulted in sky-rocketing prices that have hit the poorest segments of Egyptian society the hardest.

The role of the armed forces, one of the taboo subjects under Mubarak, has become one of the main bones of contention in postrevolution Egypt. But with a former defence minister and field marshal as president, the independence and power of the armed forces remains unchallenged as yet. The continuing crackdown on journalists and political opponents, rights campaigners and other elements of civil society also seriously hampers efforts to address Egypt’s problems. For as long as the regime refuses to consider the sort of independent, open government that is needed to address the country’s problems, the situation will likely continue to deteriorate.

Pressing Problems

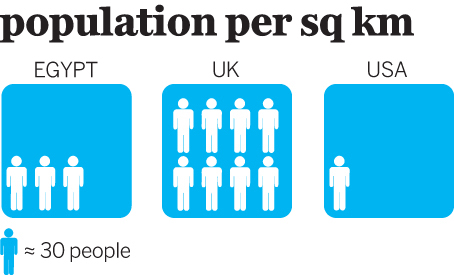

Modern Egypt is bursting at the seams. While presidents and promises have come and gone, the problems they allowed to grow remain: a booming population, notably high unemployment and a basket-case economy. Once home to the all-powerful pharaohs, the country has largely been reduced to dependency on the US, Gulf States, the EU and, most recently, to the IMF.

The list of woes continues and includes torture and ill-treatment of prisoners in detention, described by Amnesty International as ‘systematic’; the issue of child labour, particularly within the lucrative national cotton industry (UNICEF reports more than one million children are believed to work in this industry alone); regularly reported cases of ‘administrative detention’ of individuals without trial, including many pro-democracy activists, which has brought criticism from both local media and international human-rights organisations; continuing restrictions on women under personal-status laws, which, for example, deny the freedom to travel without permission, now compounded by a growing problem of sexual harassment; rampant inflation, leading to food shortages within the poorest communities; and constant environmental threats, with polluted waterways, overpopulation, unregulated emissions, a looming water crisis and soil salinity being of serious concern. Most obvious for the visitor is a crisis in tourism: the crowds that used to throng the temples and tombs now stay on the Red Sea beaches, or at home.

Eternally Egypt

Even in postrevolutionary Egypt, some things have remained unchanged, such as lingering over coffee in one of Alexandria’s cosmopolitan cafes or sipping a calming glass of shai (tea) after a frenzied shopping episode in Cairo’s Khan Al Khalili. Magnificent monuments are everywhere – the pointed perfection of the Pyramids and the majestic tombs and temples of Luxor are some of the wonders that generations of visitors have admired during their city sojourns, jaunts up and down the Nile and expeditions through spectacularly stark desert landscapes.

One thing that can be said with certainty is this: just as the monuments that tell the story of the country’s glorious past remain, so too do the special talents that have always singled out the Egyptians – their ability to laugh and to improvise. Whether in the suffocating density of Cairo’s city streets or the harsh elements of the open desert, they remain an incredibly resilient people who find humour and optimism in the most unlikely of circumstances. While your travels in Egypt might not always be easygoing or hassle-free, they’ll certainly be eye-opening.

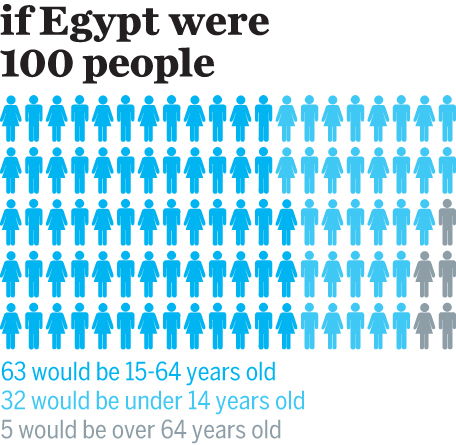

POPULATION:

95.7 million

ANNUAL POPULATION GROWTH RATE:

2.4%

AVERAGE ANNUAL INCOME:

US$6700

UNEMPLOYMENT :

12%