A preoccupation with the past, a sense of being overshadowed by one’s own classics, an elevation of the critic to an integral role in the establishment of new creative canons, even in the creative process itself—these are all phenomena that we recognize today, and to which we therefore have no difficulty in responding when we meet them in the literature of the Hellenistic period, from the third century onwards. Ransacking the past for preservable fragments, allusions, or verbal usages is a practice familiar to us from the work of Eliot, Pound, David Jones in The Anathemata, or the Kazantzakis of the Odyssey sequel.1 Today both poetry and fiction are being firmly moved into the control of academic critics, who dispute each others’ views as fiercely as ever the occupants of the Muses’ birdcage in Alexandria did (above, p. 87). Scholarship has become a necessary adjunct to creation: allusiveness and symbolism are prized, while it is by no means uncommon for the creative artist to double as a university professor, so that, like John Hawkes or John Barth, he can, if he so wishes, feed his output straight into the academic hopper for critical evaluation, without any intervening stage.

All this irresistibly recalls the practice of writers such as Callimachus or Lycophron: the ideal of the poet-as-critic (or vice versa), a label first attached to Philetas (above, p. 86), proved immensely popular. It also was one of many factors that helped to create a mandarin elite, dependent on state patronage, contemptuous of the common man, heir to all those Platonic and Aristotelian sneers at the banausic occupations, what Shakespeare was later to label as the business of “rude mechanicals,” “base, common, and popular.” These hypereducated intellectuals were writing for—and very often about—each other, and thus, like Pound or Eliot, prided themselves on their richly exotic literary or mythological references. At the same time an active distaste for the vulgarly accessible (“I abhor all public things,” Callimachus asserted)2 drove them to reject or modify those genres, the epic in particular, that had been associated with large audiences. They were, in essence, fundamentally elitist. Just as Pound embraced Italian fascism, and Eliot proclaimed himself an Anglo-Catholic royalist, so the Hellenistic poets sought lucrative patronage from absolute monarchs, in return for which even the most intellectually abstruse of them were expected, at intervals, to glorify their patrons with palpable flattery and hints of divine status. In his first hymn Callimachus associates, indeed virtually equates, Ptolemy II with Zeus (78–87), and in the second with Apollo (26–27). “From Zeus come kings,” he wrote, “for than Zeus’s princes nothing is more divine.” Zeus bestowed abundance on them, but not to all equally. “We can judge this from our lord, since he has outstripped the rest by a wide margin. What he thinks in the morning he accomplishes by evening—by evening the greatest projects, but the lesser ones the moment he thinks of them.” And again: “Whoso fights with the blessed gods would fight with my king; whoso fights with my king would fight with Apollo.”

The attacks on popular or accessible literary forms tended to be not just elitist, but also xenophobic. At the end of Hymn 2 Callimachus makes Apollo tell Envy (who has been supporting poetic prolixity): “The Assyrian river [i.e., the Euphrates] has a broad stream, but carries down much dirt and refuse on its waters.”3 Polyglot, cosmopolitan, above all Oriental influences are to be deprecated (cf. pp. 317 ff.): stick to the pure unsullied spring of the Greek Muses. Centuries later the Roman satirist Juvenal, who had very little time even for native Greeks, was to make an identical complaint about the filth washed down by the Orontes.4 Oriental syncretism, already having a huge impact on Hellenistic society, was (for that very reason) to be rejected, together with epic and the heroic ēthos that epic presupposed (p. 202).

In scholarship, as in other fields of human endeavor, Parkinson’s law applies: critics will expand their activities as far as they are subsidized to do so. Cultural parvenus like the Ptolemies or the Seleucids still looked over their shoulder to Athens for guidance. Libraries and research institutes are, by definition, dedicated to the recovery of the past. The object may be to create a platform from which to launch new discoveries, but first the existing heritage must be made secure (p. 89). The heritage in the present case was, with good reason, identified as that of fifth-century Athens, and the process of recovery and embalming had begun, like so many of these trends, long before the Hellenistic age proper. The fourth-century canonization of the three great Athenian tragedians, as early as 386 (above, p. 52), shows this very clearly; Aristotle’s attempts, in his Poetics, to define the genre according to fifth-century terms and examples merely confirm it. All the collecting, cataloguing, textual criticism, and literary evaluation that went on, century after century, in the Alexandrian Museum and other subsidized establishments was, in the last resort, backward-looking, a retrospective genuflection to classical supremacy. Athenian cults, Athenian myths, the Attic dialect, Athenian literary genres—all were researched, promoted, imitated.

At the same time this process was influenced by new social, political, even religious trends. The notion of Euhemerus (above, p. 55), that the Olympian gods were really ancient kings divinized in recognition of their achievements on earth, was one that fitted in well with the deification of Alexander the Great, or of Ptolemy Soter and Arsinoë, the pragmatism that had led even Athens to greet Demetrius the Besieger as a god manifest. This treatment inevitably found its way into all Hellenistic court poetry (not always as open flattery), since, after all, it was the new god-kings who handed out the patronage and footed the bills for poetry and research. On that basis elitism was inevitable: the political involvement of citizens under a democracy had become no more than a theory for intellectuals, rather like those Republican dreams nursed by opulent Stoic senators in Rome under the Julio-Claudians.

Further, since the academic world involved, then as now, an element of teaching—was, indeed, didactic and prescriptive by nature—we also find, along with the self-defensive smokescreen of learned obscurantism and allusiveness, a counterurge to explain things: old customs, puzzling myths, the archaic byways of art and literature; and the more recondite, the better. This aetiologizing urge stemmed in part from a genuine, if unacknowledged, longing among déraciné urban skeptics and rationalists for emotional, even religious roots that were in danger of being lost; but at the same time a kind of in-group freemasonry was also at work. A similar phenomenon is offered today by those ingenious scholars who compile keys or commentaries for Pound’s Cantos or Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Learned scholiasts flourished, while, by inverse snobbery, the idea of a simple, straightforward concept, name, or reference, a direct and unambiguous statement, became anathema. Lewis Carroll parodied this recurrent trend in a poem in which he characterized the attitude as learning to look at everything “with a sort of mental squint.”5 A would-be young poetaster asks his older mentor:

“For instance, if I wished, Sir,Of mutton-pies to tell,Should I say ‘dreams of fleecy flocksPent in a wheaten cell’?”“Why, yes,” the old man said: “that phraseWould answer very well.”

Thus the pleasure of puzzles is reinforced by the superior sense of knowing the answers to them. Further, the scholarly passion to find out what songs the Sirens sang, obscure erudition for its own sake, was in part to mask the fact that the original emotional force of the old myths was rapidly being lost in an increasingly secular, skeptical, and commercial age. Yet the emotional need was as strong as ever—nobody, in one way or another, could leave the myths alone—and attempts to satisfy it can be glimpsed here and there: the syncretic evolution of new or revamped gods through the assimilation of foreign cults (e.g., Sarapis), or the use of ruler worship to knit together the cosmic order, with dead kings and queens identified by court poets as constellations—one more reason, along with the rise of astrology (p. 595),6 for the amazing popularity of a poem like Aratus’s Phaenomena—or fancies such as the rediscovery of the lost dedicated lock from Berenice’s hair as, again, a group of stars, near the Great Bear, a comforting juxtaposition of heaven and earth. The historicization of myth, the reconciliation of old variants in credible form, was one of the main tasks the Alexandrian scholar-poets set each other.7

Epigrams, being primarily concerned with sex or death, as well as meeting the new literary requirements of jeweled brevity, flourished as never before. A genre once largely restricted to tombstones now blossomed in a wealth of literary allusion, imitation, and subtle variants for the cognoscenti.8 During the first half of the third century, besides Callimachus, we find exponents of the epigram such as Asclepiades of Samos (b. ca. 320), an innovator who broke away from old epigraphical conventions to pioneer the personal, emotional, and, more often than not, erotic epigram (also one of the “malignant gnomes” castigated by Callimachus in his prologue to the Aitia);9 and the bitter, brooding pessimist Leonidas of Taras,10 first of the vagabond poets.11 Between them Asclepiades and Leonidas sum up the antithetical extremes of early Hellenistic society. In Asclepiades, whose hedonism found sharp, controlled focus with mostly four-line epigrams, we see, inter alia, the desexualization of Eros, from elegant youth to pretty cherub,12 an evolution exactly matched in the visual arts (compare the Eros of Praxiteles with that by Lysippus),13 and culminating in the small winged putti so popular throughout the Graeco-Roman period,14 armed with the arrows that now objectified the pangs of ardent desire.

Asclepiades’ attitude to passion is on the whole lighthearted, bisexual, and cheerfully inconstant: the act, the moment of ecstasy, achieved or in prospect, is paramount.15 The agonies of frustrated love now have their own, at times somewhat masochistic, attraction, not least in the paraklausithyron, when the beloved’s door is fast shut, the suitor outside, and (a nice extra touch) the rain pouring down.16 If this poet wants, as has been suggested, “the private, the exclusive, the uncompeted-for,”17 that does not stop him writing kiss-and-tell squibs about innumerable partners of both sexes—even if he objects to a courtesan like Hermione openly professing an identical creed (in a message embroidered in gold on her sash), or mocks two Samian girls who have turned lesbian.18 (Callimachus’s erotic epigrams, in sharp contrast, are never obscene, invariably homosexual, and reveal a consistent delicacy of feeling—reasons, perhaps, why he numbered Asclepiades among the hostile gnomes.)19 Yet there is also in Asclepiades a sense of Weltschmerz, the inevitable overspill from that pathos with which he gilds his sensuality:20

I’m not yet twenty-two, and I’m weary of living:Oh Loves, why this plague, why burn me so?For if something should happen to me, I know your reaction—You’ll go on playing knucklebones, you’ll not give a damn.

Even the vanity of transience cannot here keep Asclepiades, characteristically again, from adapting a euphemism popular in wills to skirt round the fact of death.21

Here he stands in sharp contrast to Leonidas, whose concerns are (as Auden once wrote of A. E. Housman) “something to do with violence and the poor,”22 and whose Cynic possession by death not only matches Webster’s, but is expressed in language that foreshadows every memento mori in subsequent European literature:23

Endless, O man, the time that elapsed before youCame to the light, and endless time there’ll beLess than a pinprick? A brief spellOf affliction is yours, and even that lacks sweetness,Is more hateful a foe than death.Compacted from such a framework of bones, O man, can you, do youStill reach out to air and sky? See, man,How useless your striving: by the half-woven fabricA worm sits over the threads, till allWears thin as a skeletal leaf, is more abhorrentBy far than the spider’s web.Search out your strength, O man, at each day’s dawning,Bow low, be content with a frugal life, in your heartAlways remember, so long as you mingle with the living,From what jackstraw you’re made.

The expected carpe diem motif (“life’s too brief, so enjoy it while you can”) is given a savage reversal: we see here, in embryo, the self-flagellant puritanism that would culminate, centuries later, in the Desert Fathers of the Thebaid. Leonidas knew, too well, the price that hedonism could exact: there are few poems more savage than his contemptuous epigram on Anacreon (probably suggested by a well-known statue):24 drunk, gray-bearded, robe trailing, one shoe lost, “a lecherous look in his leaky eye.” Yet Leonidas could also be moved by rocks and waterfalls, by the rural simplicity of a cool spring sacred to the Nymphs, by a shepherd’s whittled dolls.25 This pastoral vision, as we shall see (pp. 233 ff.), had an increasing (and increasingly unreal) attraction for urban intellectuals.

In many ways progressive secularization, which had gained impetus as a result of the fifth-century sophistic movement, had come to undermine all the old comforting certainties. People were beginning to have serious eschatological doubts: was the whole concept of Hades, now under heavy rationalist assault, no more than an old-wives’ tale? Oddly—perhaps not so oddly—this caused serious worry. At least Hades was a place, with a traditional geography: it might be scary, but it fostered the sense of continued existence, if only as a shade, and in a conceivable locale below. “What of the underworld?” the interlocutor in one of Callimachus’s epigrams inquires of a dead man.26 “Much darkness,” comes the reply. “And resurrection?”27 “A lie.” “And Pluto?” “A fable.” “We are undone.” It is a heartfelt cry, and one that goes far to explain the salvationist cults that gain steadily in popularity from now on. The dead man’s final comment is also worth noting. He says, in effect, “I’m telling you the truth, but if you just want to hear what suits you, lies come cheap in the underworld.” By Juvenal’s day, again, things had gone farther, and, as he says, then not even small children believed in Hades any longer.28 It was left for another scholar-poet, in our own day, Louis MacNeice, to resurrect a really terrifying Charon (“his hands / Were black with obols, and varicose veins / Marbled his calves”), who announces to the would-be traveler over the Styx: “If you want to die, you will have to pay for it.”29

The whole business of rescuing the past through books has always had an oddly eclectic quality about it, and the Hellenistic operation was more idiosyncratic than most. One might suppose that what would emerge would be an age of great historiography; but even allowing for massive losses of key texts, this does not seem to have been the case. The historians, such as Phylarchus or Hieronymus of Cardia, may have existed, but they did not provide the dominant mode of inquiry (historia). This mode, in its reliance on the pre-historiographical instrument of myth, was, indeed, profoundly antihistorical. To systematize, syncretize, and expound the whole surviving corpus of Greek myth became one of the prime aims of the Hellenistic littérateurs; and that corpus (as becomes abundantly clear from Roman poets like Propertius or Ovid) was then regularly employed as a kind of exotic secular Bible, to provide precedents, exempla, warnings, or moral guidelines for human activities on earth. Throughout Ovid’s vast output of poetry, the referral—across the whole range of social or moral conduct—to mythical precedent or justification remains constant. No other comparable court of appeal existed. Thus it is clear that the anti-quarianism involved in the rescue (and, where possible, reconciliation) of variant mythic traditions was dictated, also, by a species of moral quandary that urgently needed some less coldly rational solution to ethical problems than those proposed by the philosophers. It was very far from being merely an academic game, though many academics, Callimachus not least, may have treated it as such: in various ways—by erudite systematization, by deliberate hermetic obscurantism, by literate irony and disarming ambivalence—Hellenistic writers were trying to rescue not only the mythic heritage as such, but the whole supportive moral world view, long savaged by sophists and scientists, that this heritage implied. Lycophron, Aratus, and Callimachus well illustrate the three different approaches to this pressing problem.

Just how recherché the process could become, and how obsessed with the mandarin pursuit of referential allusiveness and obscurity for their own sakes, we can see at once in that extraordinary poetic tour de force, the Alexandra of Lycophron. Lycophron of Chalcis (b. ca. 330–325) came to Alexandria about 285/3, eventually to work in the Library for Ptolemy II,30 cataloguing the collection of comic playwrights, and writing a treatise on comedy as such;31 he was also a prolific tragic poet, one of the seven included in the so-called Pleiad.32 But it is his “obscure poem,” as it was described even in antiquity,33 for which he was, and still is, remembered. The Alexandra is a slave’s report to Priam of Cassandra’s prophecies concerning the destruction of Troy, the subsequent fortunes of the Greeks, the struggle between Europe and Asia, and, interestingly, the rise of Rome (this last probably stimulated by Pyrrhus’s defeat in southern Italy and the Roman embassy to Ptolemy in 273).34 The poem is 1,474 lines long, a messenger speech taking up the space of an entire play, and written in rather flat, conventional iambic trimeter verse, piquantly at odds with the exotic matter it has to convey.35 Cassandra, who “apolloed the voice from her bay-fed throat, reproducing the utterance of the dark Sphinx” (5–8), is the excuse for all the allusive periphrasis that follows; even the slave introducing her takes thirty lines to say, in effect, that on the morning Paris set sail, Cassandra began to prophesy. “The centipede lovely-faced stork-colored daughters of the Bald Lady struck maiden-slaying Thetis with their blades” (22–24) simply means that Paris’s hundred-oared ships, built of timber from Bald Mountain (Phalakra) in the Troad, painted with the apotropaic eye on their bows, hulls pitch-black, like storks (more plausible than white, the other prevalent color of European storks), dipped their oars in the sea, more particularly the Hellespont (since this claimed the life of the maiden Helle), Thetis qua sea nymph being used by synecdoche to represent the sea itself.

Every line requires this kind of exegesis, and the vocabulary is as exotic as the allusions: out of a 3,000-word total for 1,474 lines, over 500 are found nowhere else (hapax legomena), and more than a hundred appear here for the first time:36 compare Joyce, and Kazantzakis in his Odyssey. Lycophron anticipates the advice given to the young would-be versifier in Carroll’s “Poeta Fit, Non Nascitur” (above, p. 174): “And evermore be sure / Throughout the poem to be found / Consistently obscure.” At the same time it is important to note that the puzzles or enigmas (griphoi) that produce Lycophron’s obscurity have nothing to do with the Alexandras structure, poetic vision, or style, which, far from being baroque, is in the old classical tradition of tragic narrative. The mystification applies exclusively to content,37 and consists, for the most part, of simple periphrastic substitutions in nomenclature, applied frequently to mythical persons, less often to places or objects. There is a nice parallel here with Orwell’s view of Salvador Dali’s painting, which, he remarks, is highly conventional, not to say Pre-Raphaelite, in technique, and only truly bizarre in its choice and treatment of subject.38

Such an exercise is, clearly, aberrant, the idea of the sovereign power of the logos carried to more than logical extremes. One also gets the impression from the Alexandra that straightforward traditional myth was felt to be too frail a growth to survive unprotected in a skeptical world, and therefore had to be hedged about with impressively arcane mystery. As a phenomenon, this kind of allusive word play, again, has its roots back in the fifth century. The rhetorical excesses of Gorgias, the punning fantasies and self-sustained verbal utopia created by Aristophanes as Cloud-cuckooland in The Birds,39 both clearly foreshadow this kind of literary venture, where the word is, in effect, cut loose from any dependence on its social context. We know this trend today; and I suspect the underlying cause in both cases is the same. On the one hand we find a sense of political impotence, the inability to control or influence public events, leading to a withdrawal from involvement into a private world: solipsism has its verbal functions no less than its social or philosophical dimensions. On the other, there is this deliberate emphasis on arcane mystery, the assimilation of myth to a hermetic discipline.40 For Hellenistic thinkers one motive here was surely an attempt to revalidate the moral and existential macrocosm of a worldview that had found its last great exponent in Pindar, its nemesis in the sophists of the post-Periclean era.

Callimachus (ca. 305–ca. 240), like Ben Jonson, has always had a rather better press than he deserves, and for much the same reason: his academic ideals and credentials can hardly fail to appeal to those other academics, in antiquity or modern times, who have been called upon to evaluate him.41 Besides, anyone who so prides himself on restrained good taste is bound to pick up votes from latter-day hopefuls not quite sure in their own minds just what the latest criteria of good taste may be. Callimachus has always been a firm favorite among scholarly littérateurs, who, like Odysseus Elytis’s young Alexandrians in the Axion Esti, tend to mock the out-of-step dissenter. Counterattacks are rarer; but we find the Roman epigrammatist Martial contemptuously telling an acquaintance with a taste for the byways of mythology that instead of reading his, Martial’s, verse, which is about real life (hominem pagina nostra sapit) he should, obviously, bury himself in Callimachus’s Aitia.42 Nothing shows better how far, beginning in the fourth century, literature moved away from the public arena, to become the property of a private, very often subsidized, intellectual minority, than the pervasive educated taste for Callimachus throughout the Hellenistic period. He is more quoted on papyrus, by grammarians, critics, lexicographers, metricians, and editors, than any other poet except for Homer. A North African from Cyrene, with strong Dorian roots, Callimachus never, as far as we know, visited Athens; but then, Arthur Waley never set foot in China. As a young man Callimachus was an obscure schoolmaster in a suburb of Alexandria, but somehow caught the attention of Ptolemy II, who gave him substantial backing for life.43 One tradition asserts that he got his start as “a youth around the court,”44 a claim that has puzzled scholars;45 looked at in a context of homosexuality (below, p. 182) and literary patronage, it seems clear enough.

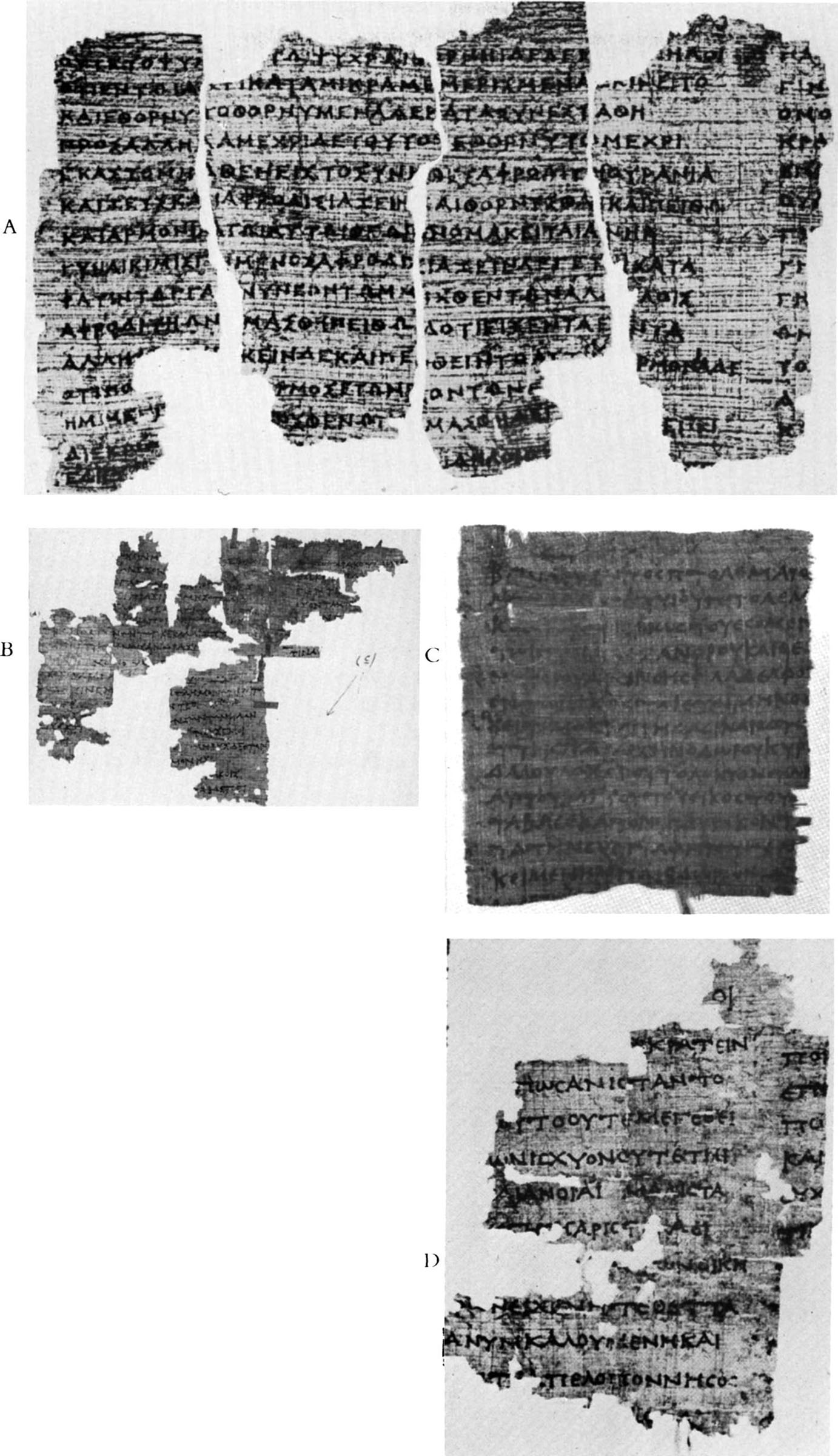

Callimachus may have frowned on big books, but can hardly have objected to multiplicity of titles, since his own overall literary output was enormous: eight hundred volumes (i.e., papyrus rolls), according to that catchall Byzantine lexicon the Suda. Though this total is almost certainly exaggerated, he undoubtedly wrote a great deal: hymns, epigrams, iambics, epyllia, and, inevitably, occasional court poetry for his patrons, ranging from an epithalamium for Arsinoë’s wedding to the ode describing her death and subsequent deification, or the related elegy on the enskyed Lock of Berenice, written not long before his death (ca. 240).46 His long and rancorous feud with Apollonius, who favored, and wrote, literary epic (below, pp. 201 ff.), did not stop him, in his first Iambus,47 from advising his literary colleagues to avoid quarrels and backbiting. His own lampoons are full of literary allusions, but lack the real bite of an Archilochus or a Hipponax. Though given the enormously responsible task—which he carried out with distinction—of producing a catalogue raisonné of the Library’s holdings, the famous Pinakes, or “Tablets,” in 120 volumes,48 he never held the post of chief librarian.

Again and again in his mannered explorations of the Greek mythic heritage Callimachus attacks stale themes and bloated rhetoric, extols the virtues of restraint, good taste, purity, brevity.49 As a program this wins our respect, but its execution is often disturbing. Its author is also constantly engaged in polemics, both attacking others and justifying himself against criticism. Students of Pound will find themselves in familiar territory. Hymn 2, after its slash at ornate and diffuse Orientalism, ends with a direct appeal to Ptolemy: “Farewell, my lord: may Criticism dwell where Envy is.”50 He returns to the attack in his prologue to the Aitia (“Causes”), a longer poem of which only tantalizing fragments survive.51 This odd work, recently claimed as a kind of countergenre to epic,52 is in fact little more than a loose rag-bag offering a series of aetiological explanations for odd customs. The lock of Berenice, the myth of Acontius and Cydippe, ekphrastic accounts of various archaic statues, puzzling temple rituals, even the invention of the mousetrap (fr. 177): all are dragged in somehow. The obsession with the past is all-consuming. Sometimes—a recurrent problem ever since Xenophanes, in the sixth century, censured Homeric and Hesiodic morality53—the past can be embarrassing: on the verge of describing Hera’s sacred but incestuous marriage to Zeus (fr. 75.4 ff.), Callimachus apostrophizes himself: “Dog, dog! Restrain yourself, my shameless spirit! . . . Much knowledge is a sore ill for anyone who cannot control his tongue; he is like a child with a knife.” The heritage sometimes calls for diplomatic sanitization: certain archaic crudities are hard to swallow in this more genteel age. Discussion of the aitia is hung on various fairly lame devices, such as a drinking party where the abstemious narrator asks his neighbor,54 as the wine is going round for the third time, “Why is it the tradition of your country to worship Peleus, king of the Myrmidons?” In the prologue, a late addition, he slashes away at malignant gnomes like Asclepiades,55 who decry his poetry because he failed to produce an epic, preferring the pared-down poem, the “back roads” of literature (not originality so much as the rare and exotic). By the time that prologue was written, the quarrel had been going on for thirty years, a literary analogue to the Funeral Games. I find this a sobering thought.

The Aitia is no fuller of recondite scholarship than Callimachus’s one venture into epic subject matter, the Hecale,56 which describes how Theseus spent a night in the hut of an old woman, the Hecale of the title, on his way to subdue the bull of Marathon. The actual feat seems to have been briefly, even casually, described (frr. 258–60): with demure wit Callimachus characterizes the captive bull, being dragged back to Athens, as a “sluggish traveler.” What really interests him is the evening discussion between Theseus and Hecale, a peg on which he can hang endless snippets from early Attic legend, the raw pabulum for yet more of that aetiologizing, which exerted as powerful a lure on the scholar-poets of Alexandria as allegory did on the medieval schoolmen. It has recently been suggested that there is social significance in the choice of protagonist here, that the socially inferior (but morally shining) Hecale represents a conscious rejection of Aristotle’s insistence on the lower orders’ being fit for presentation only on the comic stage.57 There may be something in this, but it would be unwise to press it too far: Callimachus’s conservative, antidemocratic nature makes him an unlikely candidate for radical innovations of a socially progressive sort (below, p. 182). On the other hand, it was widely believed, even in antiquity, that with the Hecale Callimachus was consciously counterattacking those who had long mocked his apparent inability to produce a long (i.e., epic) poem.58 This too is possible, though the mockery can hardly have been stilled by a work that took up no more than one book in the collected edition, and was probably little more than a thousand lines in length. More important, I think, is the impulse that sent Callimachus in pursuit of this somewhat obscure topic at all, grubbing through volumes of local Attic history (possibly including Philochorus, who also supplied material to Plutarch)59 to give the myth a new lease of life.

By comparison the Hymns, though they too never miss an opportunity for exotic aetiological glossing, stand in a more conventional tradition. They also make good propaganda. It was politic to celebrate Delos in the 260s, when the Ptolemies controlled the island and its cult:

Windscoured that island, untilled, wavebeaten, fixedIn the deep, better running for gulls than horses; the seaRoiling fierce round it sloughs out a mass of scurfTheir home there.

But such passages of straight description are rare, the poem being for most of its length clotted with mythological detritus and aetiological signposting; even visiting merchant seamen

do not return on boardTill they have been whipped around the circuit of your GreatAltar, to gnaw at the olive tree’s sacred trunk,Hands bound behind their backs, something the nymph of Delos(Ibid. 320–24)

Hymn 1, the Hymn to Zeus, in addition to a whole mass of erudition on divine origins, and some not-so-sly digs at the conflicting traditions of Zeus’s birth, also portrays kings as the god’s vicegerents on earth, and stresses that “than Zeus’s princes nothing is more divine.” But some kings, of course, are more equal than others, and the wisdom of Ptolemy is sans pareil.60 Earlier precedent for this kind of literary genre must be sought not only in the Homeric Hymns, but also in that last archaic repository of privilege and kingly status, Pindar. There is an interesting similarity between the encomia of Callimachus and those that Pindar lavishes on his clients, the Sicilian nabobs, or that ill-fated monarch Arcesilas IV of Cyrene, Callimachus’s own birthplace. Callimachus in fact adapted the Pindaric epinician ode as an elegy to celebrate a victory in the boys’ double race by Sosibius.61 Sosibius went on to become a famous, indeed notorious, minister under Ptolemy IV (below, p. 289): he was suspected not only of complicity in the murder of Ptolemy’s mother, Berenice II (the same whose lock of hair reappeared as a constellation), but also of forging the king’s will to his own advantage.62

Callimachus’s waspishness to his rivals was matched only by his servility to the great: not for him Samuel Johnson’s definition of a patron. Sosibius is described as being “friendly in his relations with the people, and not forgetful of the little man, a thing one rarely finds in the wealthy.”63 Knowing Callimachus’s constant preoccupation with his own alleged poverty, we may suspect that the argument was, as so often, ad hominem. Callimachus has had plenty of praise in the past. A. W. Bulloch, in the Cambridge History of Classical Literature, lauds him to the skies: “The most outstanding intellect of his generation, the greatest poet that the Hellenistic age produced” (p. 549), though the precise nature of this greatness remains elusive. Professor Hugh Lloyd-Jones eulogizes him as “a wit, a dandy and an ironist,” whose impact on Roman literature (and here I would agree) was incalculable: “Without Callimachus it is hard to imagine what Augustan poetry would have been like.”64 Conceivably, less artificial. Despite such glowing testimonials, I cannot help finding him at once pretentious and faintly distasteful, a literary exhibitionist with an unpleasant groveling streak about him, a sycophant implacable in his attacks on rival sycophants, a baroque and overworked scholar-poet who, even allowing for occasional flashes of mordant wit, and a handful of fastidious erotic epigrams, wears his erudition with self-conscious panache, and succeeds, when he does, in spite of it.65 Perhaps his most striking virtue, apparent even in his most pedantic and allusive passages, is his precise economy of language.

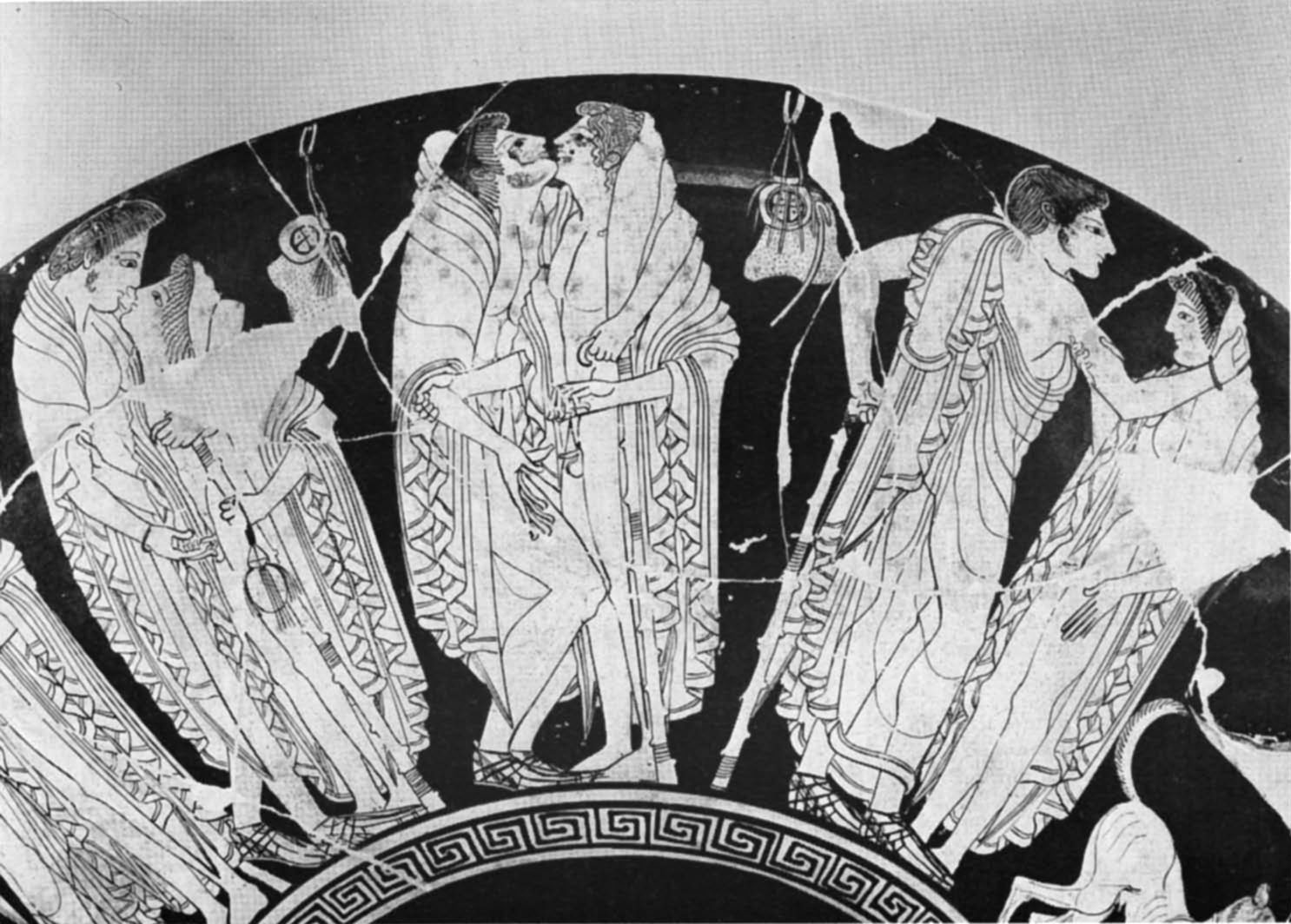

Yet at the same time his value as a witness to social trends is enormous. His abhorrence of “all public things” was political and class-based as well as literary. Such an attitude never functions in a void, not even for occupants of ivory towers; and in this case it reveals a shrewd sense of accommodation to the status quo. The poor schoolmaster from Cyrene could not only justify his position as royal client, but also satisfy his high social aspirations, by associating himself with a line of blue-blooded, antipopulist poets and thinkers from Theognis and Heracleitus through Plato to Cleanthes. Nor is it any accident that he staked his claim to exclusivity in an erotic epigram (see n. 2, p. 775). Homosexual rather than bisexual by temperament (some of his erotic verse foreshadows the Alexandrian amitiés particulières of Cavafy), he could cite excellent precedent for regarding his sexual preferences, too, as socially and culturally superior to the heterosexual ēthos now rapidly gaining ground throughout the Greek world.66 Here he is harking back, antiquarian as always, to that aristocratic tradition so jealously cultivated by the old-fashioned Athenian kalos k’agathos (aristocratic gentleman), the tradition associated with the kalos vases and other, more explicit, painted scenes of upper-class pederasty in the late archaic period (570–470), and which later provided the elitist homoerotic mystique underpinning Platonic dialogues such as the Charmides, the Phaedrus, or the Symposium.67

Women, for Callimachus, were clearly one of the “public things” (dēmosia) that he had rejected, together with populist democracy. At the same time, a sinecure under the Ptolemies exacted other, less palatable compromises. To swallow authoritarian government was easy enough, a mere acceptance of the Zeitgeist. However, the security of the Museum also meant coming to terms in some way with the ostentation, vulgarity, and gigantism inherent in the Ptolemaic ēthos, and without fatally offending one’s royal paymaster. This may possibly in part explain Callimachus’s big-book-big-evil doctrine, his sustained assault on the literary gigantism of his rivals: it is tempting to see in Apollonius a displaced substitute target for the Ptolemies themselves. Callimachus, and many lesser literati like him, were natural candidates for admission to an intellectual enclave whose members were learning to live—and, at a price, to live well—off the surplus income of commercial absolutism. There is a nice irony about the fact that the liaisons of this social aspirant, this fastidious non-drinker from public fountains, should nevertheless have been with youths who, if not actual prostitutes, were still unpleasantly mercenary and rapacious,68 and in the Athens of Demosthenes or earlier could well have been liable to prosecution.69

Aratus of Soli (ca. 315–240/39)70 was in ways a very different character from Callimachus and Lycophron, though he won high praise from the intellectuals of the Alexandrian court, Callimachus himself included.71 His patronage came from Antigonus Gonatas (above, p. 142), and thus had a Stoic core, which shows clearly in his surviving work. (It is true that between 274 and 272 he moved to the court of Antiochus I, but this was merely because during those years Antigonus had been ousted from Pella by Pyrrhus, and was battling to win back his kingdom: scholarship and philosophy had to be suspended for the duration, while the scholars themselves sought less mouvementé areas. As soon as Antigonus was reestablished, Aratus returned to Pella: it seems to have been his natural center.) It was, traditionally, at the request of Antigonus himself that Aratus composed the Phaenomena, essentially a versification of two prose treatises, one by Eudoxus (see p. 459),72 a name meaning “of good repute” (Antigonus claimed that Aratus had made Eudoxus’s repute better, had improved his doxa),73 and the other, on weather signs (sēmeia), by Theophrastus. The versification was skillfully and at times imaginatively done, though the astronomical knowledge proved to be shaky in places, as Hipparchus and others lost no time in pointing out.74 But for us there are two fundamental questions: first, why was it done at all? And second, what gave the poem its immense, and enduring, popularity, so that Cicero, Germanicus, and Avienus all translated it (even though Cicero sniffed at Aratus’s actual expertise)?75

As regards the first issue, it remained true that, in an age when the communication of knowledge was still predominantly oral rather than literary, a didactic poem of any sort was easier to memorize than a treatise in prose. More to the point, the movements and positions of stars had been of crucial importance to sailors and farmers for centuries. (The litany of epitaphs for drowned sailors is a leitmotif running through our corpus of Hellenistic epigrams.)76 But this was by no means all. On the one hand the Hellenistic period witnessed a great advance in scientific astronomy (pp. 459 ff.): stars were, so to speak, very much in the air. This, however, was not Aratus’s prime interest in the topic—nor, it is safe to say, the chief concern of his readers. What attracted them was something in fact fundamentally antiscientific, a trend very much associated with Stoicism: the use of the constellations to demonstrate cosmic order and morality. It is noteworthy that when Aratus gets to Eudoxus’s investigation of the complex stellar movements of the planets he simply omits the whole section (453 ff.), with the offhand comment that they are all vagrant and unpredictable, and beyond his competence:77 “With these, my courage fails; may I prove adequate / To describe the circles of the non-wandering stars and their signs in the firmament” (460–61). One obvious reason for his avoidance of such a topic, apart from its technical difficulty, was the Stoic search for universal cosmic order as a model reflecting ideal right government on earth: viewed in these terms, the wandering planets were anomalies, and indeed too uncomfortably like Hellenistic politicians for his or his patrons’ tastes. Hence his excursus on Justice (98–136), and his highly Stoic, not to say pantheistic, opening invocation to Zeus:

From Zeus be our commencement, whom we mortals neverLeave unnamed: full of Zeus are all the highways,All men’s market centers, full the oceanAnd harbors: in all ways we all have need of Zeus.For we are also his offspring, and he in his compassionFor mortals gives favoring signs [cf. 772], rouses nations to work,Reminding them of their livelihood, says when the soil is fittestFor oxen and mattocks, says when the seasons favorTree-planting, the sowing of every kind of seed.Himself it was that fixed signs in the heavens,Sorted the constellations, figured out the year—Which stars above all should mark each changing seasonSo that all things might flourish unfailing: whereforeMen ever set him first and last in their prayers.(Phaen. 1–14)

Following Hesiod78—Callimachus said, perhaps a little waspishly, that Aratus had skimmed off the honey from Hesiod’s work79—he sketches the Gold, Silver, and Bronze Ages; but despite the “maiden Justice” of Hesiod,80 it seems to have been his own (Stoic?) notion to equate the constellation Virgo with Dikē, Right Justice, now in retreat from earth among the stars, and thus to promote an essentially optimistic view of divine government.81 Again and again the Phaenomena demonstrates an all-pervasive belief in the rule of divine wisdom, rational and symmetrical, throughout the universe. This highly unscientific way of thinking not only developed ideas taken from the Platonic (?) Epinomis, but also opened the way toward another characteristically Hellenistic phenomenon, the pseudoscience of astrology (below, pp. 595 ff.), since one central tenet in this tradition was the belief that the stars could somehow record, reveal, or even influence human conduct. “Not yet have we mortals learned everything from Zeus,” Aratus observes, “but much is still hidden, of which Zeus will give us later if he so wills” (768–71). How anyone could describe this as “the confident voice of the man who recognizes the march of science” eludes me:82 it is the voice of religious obscurantism personified, the abrogation of reason.

What is historically significant about this poem, of course, is its best-selling impact. It highlights for us, as nothing else could, the other face of Hellenistic culture. What it offers is everything that scientific progress ignored: belief, faith in an ordered cosmos divinely set up and maintained, moral and ethical guidance to match practical instructions covering the regular, recurrent, and predictable year cycle. It not only borrowed from Hesiod; in many ways it was a throwback to modes of thought that Hesiod himself, with his primitive taxonomies, was struggling to slough off, a reaction against the freethinking rational inquiry that had been the mainstay of classical intellectual progress. While a minority of (often atheistic) scholars continued their priceless work in astronomy and mathematics (pp. 453 ff.), the majority—including the Stoics, and thus those kings and rulers who were advised by them—listened with increasing fervor to the music of the spheres. “The multitude,” said Cleanthes, Zeno’s successor in the Stoa, “has no intelligent judgment . . . you will find such only in the few”;83 yet it was Cleanthes, too, who argued that the Greeks should prosecute the great astronomer Aristarchus of Samos for impiety, because of his heliocentric theory, that “the fixed stars and the sun remain unmoved, and that the earth revolves about the sun.”84 Till Galileo’s day the moralists, theologians, and astrologers held the field. Aratus offered that immensely attractive temptation, a morally certain universe; no one was eager to believe Aristarchus’s psychologically disruptive theories.