“The starting point for my treatise,” Polybius wrote, “will be the 140th Olympiad [= 220–216 B.C.]. . . . In earlier times the affairs of the inhabited world [oikoumenē] had been, as it were, scattered, since enterprise, consummation, and locality remained separate in each instance; but from this turning point onwards history emerges as an organic whole: the affairs of Italy and of Africa are interwoven [symplekesthai]1 with those of Asia and of Greece, and all things point in concert to a single end.”2 That end, of course, was the rise of Rome to supremacy in the Mediterranean, and to achieve its delineation meant writing “universal” or “general” history (ta katholou graphein), a virtually new concept.3 “Who,” Polybius asks, “is so indifferent or indolent that he would not want to know how, and under what form of government, almost every part of the oikoumenē came under Rome’s sole rule in less than fifty-three years, an unprecedented phenomenon?”4 Who indeed? It was to answer this question, in the first instance, that Polybius wrote his Histories—or at least the first part, covering the period down to 168; the second part (167–146) sought rather to evaluate Rome’s achievement for future generations, not in terms of success or failure (over which there could be no argument), but according to moral criteria.5 Significantly, he seldom implies that that achievement is good himself.

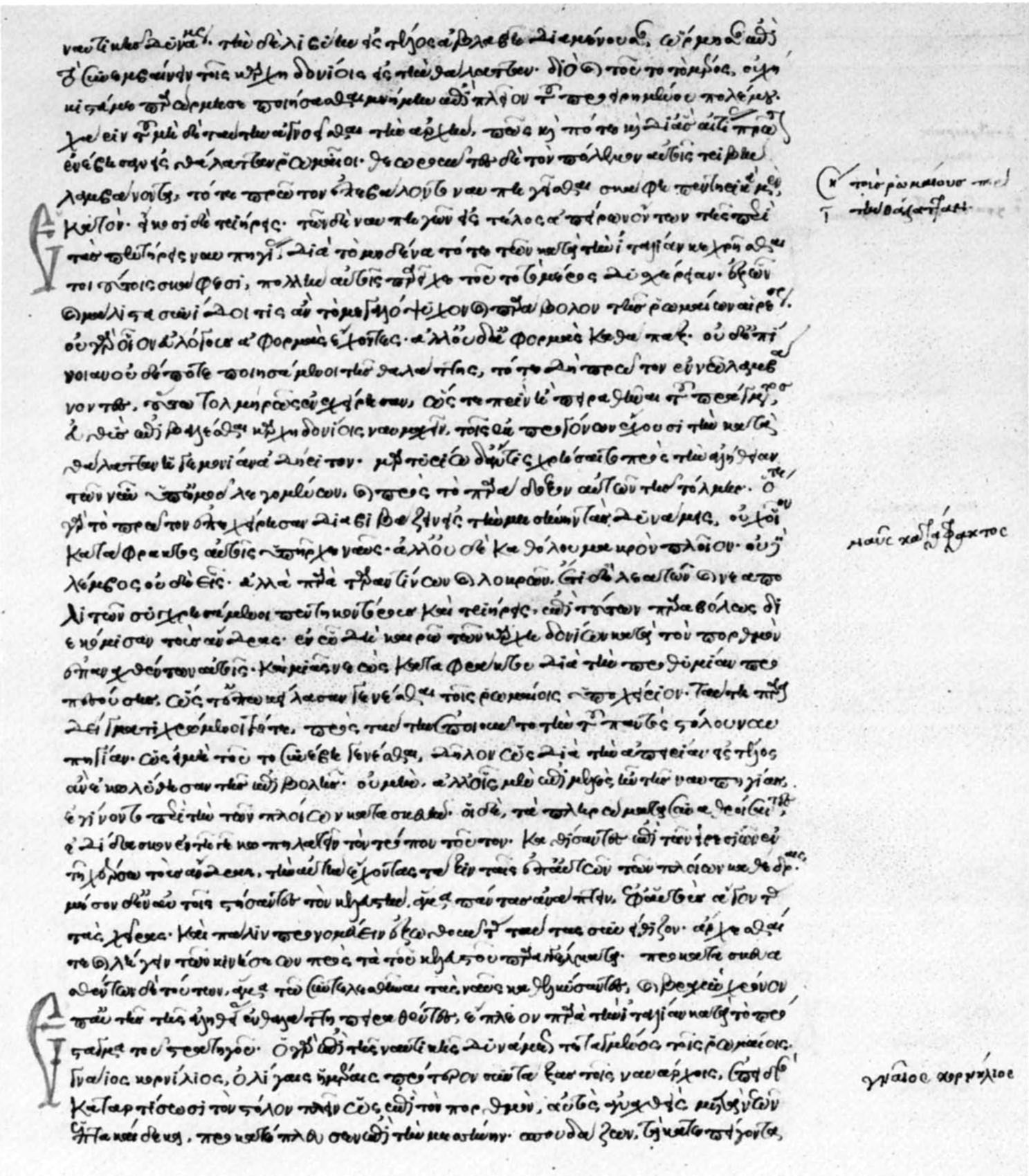

Of the forty books into which the Histories were divided, we have the first five intact, and substantial fragments from all the rest except 17, 19, 37, and 40 (which consisted of the general index). The structure of the first thirty books seems to have been loosely hexadic, with Books 6 and 12 as natural dividing points, presenting two general discussions, on political systems and historiography, respectively, and the next two hexads (Bks. 19–24, 25–30) each covering a period of four Olympiads (146–149, 150–153).6 The apparent modification of structural plan, especially in the last ten books, is almost certainly due to Polybius’s decision, in mediis rebus, to continue his work beyond the watershed of Pydna (June 168: see p. 430) and take account of the destruction of Corinth and Carthage in 146. The precise point at which the plan was revised, the number of books already written (and published), the degree to which the change necessitated revisions in books previously written, and the date at which the complete work became available are questions that have all been fiercely debated and to which no final answers can be given.7 It seems likely that the point at which Polybius changed his mind was after Corinth fell; that Books 1–5, and perhaps 6, had been published by about 150; that the last ten books were not finished till after 129;8 that he was still revising and adding to the Histories at the time of his death (ca. 118; passages in Books 1–15 appear to have been added after 146, and there are traces of revision throughout);9 and that in consequence the finished work only appeared posthumously.10 Even these assumptions are far from certain, and anything beyond them is pure guesswork.11

Polybius called his study a pragmateia, a practical treatise or guide. Not for him the aim of some Hellenistic historians, to give enjoyment (terpsis); what he offered was useful advice (ōpheleia). His work was to be pragmatikē, realistic, rational, Thucydidean,12 politico-military, shorn of genealogical and mythical fictions, and based, where possible, on autopsy;13 but also apodeiktikē, analytical, demonstrative, scientific in method.14 Despite polite genuflections to his Roman readers, he was really aiming at Greeks. His declared purpose was to provide useful matter for statesmen (he had been one himself); to chronicle the course of events between Philip V’s clash with Rome in 200, the final Macedonian defeat at Pydna in 168, and the sack of Corinth and loss of Achaean and Macedonian independence in 146 (he had been either eyewitness or participant in much of the history he wrote); and, finally, to teach men how to face disaster (a lesson, again, that he had learned from bitter personal experience). The powerful ad hominem motivation that, despite disclaimers, pervades Polybius’s approach to his task as a historian is everywhere in evidence.

As an individual, an Arcadian, a Greek, a former soldier and statesman, he had to swallow the bitter humiliation of defeat, loss of independence, eclipse by an alien power, deportation sine die. He had to come to terms with new realities, to learn how to live with the Romans while, at the same time, still being able to live with himself. To that extent his history cannot help being an attempt to rationalize as inevitable what he had been powerless to prevent. History minus truth, he proclaimed, is as useless as an eyeless creature;15 but the vision in his case remains astigmatic. Hence his intriguing, and at times self-contradictory, obsession with that characteristically Hellenistic concept Tyche16—by turns, and often simultaneously, Chance, Luck, Fortune (both malign and benevolent), Providence: the random factor, Fate’s guiding hand, the unpredictability of things. Polybius quotes Demetrius of Phaleron on the downfall of Persia, the astonishing rise of Macedonia. “But notwithstanding,” Demetrius wrote, from equally harsh experience, “Tyche never accommodates herself to our life, always comes up with some new twist to defeat our calculations”; and he went on to predict the fall, in time, of Macedonia also, a prediction, trite enough in itself, that made a deep impression on Polybius.17 It also provided him with a unifying theme. If Tyche brought the oikoumenē under Roman control, then Polybius could write the universal history of that process. Tyche, in short, is crucial to his historiography.18

His escape clause is that Tyche can be invoked as an explanation only when no rational cause for an event appears possible:19 those “acts of God” that are the nearest approach by insurance companies to theology.20 In practice, however, he does not always stick with this working rule, least of all when dealing with Rome. Tyche, he implied, willed Rome’s meteoric rise in half a century;21 yet the Romans also, or alternatively, brought this result about by their own merits, qualities, and efforts. We sense a psychological double bind here. Polybius had seen the Romans in action: he knew at first hand, better than many, just how their formula for success worked. Yet at the same time, as a Greek, he needed some palliation for defeat. So extraordinary a phenomenon as the triumph of Rome had to be providential; and if providential, then, by mere mortals, irresistible.22 Thus, though men frequently attribute to Tyche what is really the result of human action,23 rational causation and the workings of Tyche are interdependent, and best invoked together. Tyche may dictate the overall shape of events, but within this pattern man can, up to a point, make his own decisions.24 Polybius’s position here is not all that far from the cautious stand on Moira (Fate) taken by Herodotus.

What is more, having created a device to relieve his countrymen of ultimate responsibility for succumbing to the Roman takeover, he can then be as rational as he pleases in dealing with excesses of religious or superstitious credulity. Predecessors who claimed that no snow or rain ever fell on a certain open-air statue of Artemis, or that anyone entering the holy of holies in Zeus’s mountain shrine in Arcadia at once lost his shadow, are given very short shrift. To believe what is not only unreasonable but impossible, Polybius argues, has to indicate either “childish naïveté” or a “feeble intelligence.”25 This does not mean that he was a consistent intellectual rationalist. Like Herodotus again, he reveals an odd mixture of credulity and skepticism. His general attitude might most charitably be described as incoherence tempered by Euhemerism,26 with the political cynic preponderant, though not always in complete control. His attitude to Roman religion is predictably ambivalent. He is well aware (how could he not be?) that Rome swarms with religious ceremony, that numen is all-pervasive: in fact he describes superstition (deisidaimonia) as “the thing that holds the Roman state together.”27 This admission he hastily justifies by the claim that the Romans “have acted thus for the sake of the common people,” who, being “flighty and full of lawless urges, irrational passion, and violent rage,” need to be “restrained by impalpable fears and suchlike mummery”—an opium-for-the-masses thesis that recurs elsewhere,28 and is strikingly reminiscent of the ideas propagated by that fifth-century authoritarian Critias in his Sisyphus.29

Polybius, in short, comes across, for various reasons, as a historian whose center is not quite in the middle; and it is worth looking at his career with this in mind, not least since for over half a century of crucial Hellenistic history he remains by far our most serious witness. He was born about 200 in the Arcadian city of Megalopolis,30 some twenty-two years after it had been destroyed by Cleomenes (above, p. 261: it was rebuilt soon after the Spartan defeat at Sellasia). Cleomenes, as we have seen, gets very short shrift in the Histories. Polybius’s father, Lycortas,31 was a distinguished Megalopolitan statesman, several times generalissimo (stratēgos) of the Achaean League, and a close friend of Philopoemen, another Megalopolitan, whose career in the League followed an identical course. Both men represented a limited, and somewhat intransigent, attitude in politics: they sought a united Peloponnese under Achaean leadership, with Sparta neutralized and made a member of the League. (In 188 Philopoemen, with Rome’s tacit approval, was actually to demilitarize Sparta, and abolish the old Lycurgan constitution: see p. 423).32 They also favored alliance with Ptolemaic Egypt in return for regular financial support, and a somewhat ambivalent policy of neutrality toward Rome in her dealings with Macedonia and Greece.33

This was the atmosphere in which the future historian grew up, and it left an indelible mark on him. He was perhaps four or five when a Roman proconsul, Titus Quinctius Flamininus, proclaimed the freedom of the Greeks at the Isthmian Games of 196 (p. 311), and seven at the time of the Roman military evacuation (194). Throughout his early adolescence the Achaean League was fighting both the Aetolians (for whom, again, he seldom has a good word) and the Seleucid Antiochus III. Since his father was a wealthy gentleman landowner as well as a League politician, Polybius grew up with a passion for riding, hunting, and the outdoor life34—pursuits that later stood him in good stead when dealing with Roman aristocrats. He also was constantly exposed, from an early age, to the world of practical politics. He tells us of an occasion during his adolescence when he heard, and had very sharp moral reactions to, an angry debate between Philopoemen and the current League general.35

It is clear that he early adopted as his own the views of Lycortas, Philopoemen, and their circle, which called for collaboration with Rome “only within the strict conditions of the Achaean laws and the Roman alliance.” This he terms an “honorable” attitude, as opposed to the “specious” subservience of pro-Roman extremists such as Aristaenus.36 In fact, a point that Polybius himself elsewhere makes clear, during Aristaenus’s year as stratēgos (188/7) Achaean policy abroad was aggressively independent, and conducted largely without reference to Rome:37 Polybius’s local prejudices need careful watching. Similarly, the impression he gives that from 180 Achaean policy was dictated by the pro-Roman group is simply untrue: the Lycortas caucus retained all its influence,38 and suspicion grows that what Polybius is really trying to do is exculpate his father from association with the decisions that led to Pydna. His position is made abundantly clear by the fact that, aged eighteen, he was chosen to carry the urn containing Philopoemen’s ashes at the latter’s state funeral (183/2),39 and afterwards composed, in three books, an encomiastic biography of the dead statesman, probably his first published work.40

He was also, as Lycortas’s son, being groomed for high office. The mere fact of belonging to his father’s circle constituted a political education in itself. Polybius must, from childhood onwards, have heard the arguments for and against coexistence and compromise with Rome thrashed out a thousand times. In 181/0, though still well under the official age limit of thirty,41 he was chosen, together with his father and the grandson of Aratus, to serve on an embassy to Ptolemy V Epiphanes. Ptolemy had renewed the old Lagid alliance with the League (p. 249: 182/1?),42 negotiating through Lycortas for the supply of arms and cash, and now promised a naval squadron, for the acceptance and delivery of which the Achaean delegates were to be responsible.43 The mission was canceled because of Ptolemy’s death, but the honor, for a young man in his early twenties, remained outstanding. By 170/69—presumably after considerable experience of soldiering in the field, though for this we have no direct evidence44—Polybius had, at the youngest possible age, been appointed cavalry commander (hipparchos) of the League:45 this position was political as well as military, and normally formed the stepping stone to election as stratēgos.

Thus Polybius was deeply committed both to the League and to his own career within it. As we have seen, his political group favored an independent neutralism with regard to Rome, an attitude that made its members suspect both to the pro-Roman Achaean party and to the Romans themselves.46 The times were to test this policy severely, and Polybius was to modify his own attitude enough by 170, whether on principle or for more pragmatic reasons, to oppose his father in the Achaean assembly.47 Since 172 Rome had been at war with Macedonia (the so-called Third Macedonian War), a conflict that was to end in 168 with the total defeat at Pydna of the Macedonian king Perseus (pp. 427 ff.). The attitude of the Achaean League was, from Rome’s viewpoint, by no means satisfactory. Its leaders were not only divided among themselves, but also, clearly, hedging their bets, since as late as 171 a standoff between Rome and Macedonia did not strike even Polybius as wholly out of the question.48 Two Roman envoys who visited the Peloponnese in 169 found that, in their opinion, certain leaders of the League were unfriendly to the Roman cause, and named, among others, Lycortas and Polybius.49 They had not, in point of fact, actively promoted defection from the Roman alliance; but their support for it had been, at best, lukewarm.50

It is true that the Roman definition of “unfriendliness” (inimicitia) seems to have included anything short of total and sycophantic collaboration, the kind of attitude encouraged (if we are to believe Polybius) by the Achaean pro-Roman group under the leadership of Callicrates. Now in 180 Callicrates had been the spokesman of a notorious embassy to Rome—notorious largely through Polybius’s venomous account of it.51 In his version, Callicrates urged the Romans to wake up to the hostility and intransigence of the dominant party of Lycortas; were Callicrates, Hyperbatus, and their group in power, they would ensure that Achaean policy—indeed the very law of the land—was wholly subordinated to Rome’s will. The offer, Polybius claims, was enthusiastically endorsed, and from then on Rome consistently supported such sycophants while ignoring wiser if less toadying friends in Achaea. In this version the opposition to Rome is associated with populist politicians and the mob; its removal, with Callicrates and his upper-class supporters.52

There is, clearly, much to arouse suspicion in this account, and its widespread acceptance at face value as a turning point in Roman-Greek relationships—with liberal scholars denigrating Callicrates, while conservatists or realists praise him as “a far-sighted statesman whose actions were conducive to the welfare of Achaea,” what might be termed the Laval syndrome53—comes as something of a surprise. In the first place, Polybius had powerful motives for doing a hatchet job on Callicrates, who was not only his father’s leading opponent, but also (as we shall see) the person directly responsible for Polybius’s own seventeen-year exile. Second, the narrative bristles with inconsistencies and implausibilities. Can we really believe that any Achaean politician would urge his fellow countrymen to place the interests of Rome above their own laws and constitution, or, if he did so, that he would then be delegated to go to Rome and present the opposition’s case?54 Further, though Callicrates, as spokesman, claims that his party is out of favor in Achaea, the mere fact of his presence there before the Roman Senate, as ranking member of an Achaean embassy, officially delegated, ipso facto disproves such an assertion.55 What is more, the stratēgos for that year (181/0) was his henchman Hyperbatus.56

We need not doubt, then, that Callicrates’ speech was conciliatory to Rome (by no means a new departure),57 nor that it pleased the Senate, nor that it aimed, inter alia, to embarrass Lycortas and the Achaean opposition, which there are some signs that it did.58 But just as Polybius erred from the truth in claiming that Callicrates and his group were out of power at the time of the 180 embassy, he is equally misleading in his suggestion that from then on they, hand in glove with Rome, dictated Achaean policy. It is true that Callicrates himself was elected stratēgos at some point after his return from the embassy (taking bribes in the process, Polybius sneers):59 but it so happens that all the stratēgoi known to us from the following decade are Callicrates’ opponents.60 The most we can say is that the embassy may have encouraged hardliners in Rome, and undoubtedly tended to deepen the divisions in Lycortas’s own party between the advocates of intransigence and those who preferred cautious compromise. Callicrates’ most concrete achievement would seem to have been the restoration of the Spartan and Messenian exiles.61 The real lesson for a modern reader is the degree of parti pris manipulation that Polybius’s narrative reveals.

After ten further years of such public political bickering it is hardly remarkable that the Roman envoys who visited Achaea on a fact-finding mission should have detected anti-Roman sentiments in some of the League politicians. What is surprising is that at the time no action was taken against any individuals on the basis of such complaints because (says Polybius) no convincing excuse for doing so could be found.62 The envoys clearly knew nothing about the brisk debate on future policy, involving Lycortas and his associates, that had taken place a few months previously.63 On that occasion some firebrands had actually spoken out in favor of disciplining the pro-Roman extremists. Lycortas himself wanted strict neutrality, while Polybius and others felt they should keep their options open, and offer the Romans aid—but only if circumstances made it desirable or advisable for the benefit of Achaea. This last view prevailed, and it was as a member of the then-dominant group that Polybius became hipparchos (170/69).

In fact the Achaeans passed a decree placing their forces at the disposal of the Roman consul in Macedonia;64 but the consul, Quintus Marcius Philippus, declined the offer when Polybius, after careful delay, acquainted him with it.65 Since the delay was obviously engineered in hope of just such a rejection, it is hard to tell (a thought that also occurred to Polybius) whether Marcius’s refusal was dictated by kindness or suspicion. A more likely motive is self-interest. Polybius himself stayed on with Marcius when the other envoys left, and (on the Roman’s secret instructions) subsequently managed to get the Achaean assembly to veto the dispatch of five thousand troops to Marcius’s opposite number, Appius Claudius Centho, in Epirus. This act pleased Marcius, who seems to have wanted to keep a rival out of action, and also saved the League something over 120 talents; but at the same time it gave Polybius’s political enemies the chance to represent him as less than enthusiastic for the Roman cause66—and who is to say that at the time they were wrong?

In any case, when, after Perseus’s defeat at Pydna (p. 430), the Romans conducted a purge of unreliable leading men in Achaea, deporting no less than a thousand of them to Rome,67 among those thus exiled was Polybius.68 His father, Lycortas, must already have been dead; otherwise he too would have been listed among the more distinguished exiles. From now on, as Polybius wrote, and had learned the hard way, it was accepted that everyone (which for him meant the Greeks of the Peloponnese) must obey Rome’s orders.69 Such control, despite the Roman partiality for legalism, could be arbitrary to a degree: neither Polybius nor any of his fellow deportees was ever put on trial, or even accused, though ostensibly they were in Italy to answer charges of not having aided Rome against Perseus. In actual fact they were partly regarded as hostages for the good behavior of those left in the Peloponnese, and partly had been shipped off out of the way to stop them making any trouble in future themselves. The list of victims was drawn up by Callicrates and his associates: Polybius is, understandably, no kinder to Callicrates than Thucydides, for a like reason, had been to Cleon.70

The position of Polybius in this group was exceptional. Most of the Achaeans were kept well clear of the capital, on various Etruscan estates. But Polybius remained in Rome, and was clearly free also to travel. This privilege he owed to the intercession, as he himself tells us, of the eighteen-year-old Scipio Aemilianus, son of Aemilius Paullus, the victor of Pydna: they had first met through “the loan of some books and conversation about them.”71 Scipio, Polybius tells us, begged for his company and intellectual guidance: there is a Socratic flavor about the whole episode. When the other deportees were being moved to provincial cities, Scipio and his elder brother, Fabius, petitioned the praetor on Polybius’s behalf, and he was allowed to remain behind, becoming a constant companion and adviser to Scipio, just as the young man had hoped.72 It is likely that Lycortas and his son had, in an official capacity, already made the acquaintance of Aemilius Paullus, perhaps when the Roman visited Megalopolis during his tour of Greece. It is even possible that Polybius actually took up residence in Scipio’s household.73

The literary and philhellenic friends whom Scipio gathered round him in the so-called Scipionic circle offered the kind of company that Polybius found most congenial: intellectual, but at the same time tough-minded and aristocratic. They included Furius, Laelius, and, later, the Greek philosopher Panaetius (below, p. 639), who probably fostered in the historian a taste for Stoicism.74 Scipio and Polybius shared a passion for hunting: this was how Polybius also made the acquaintance of a hostage of a different sort, the Seleucid prince Demetrius I, whose escape from Rome he helped to organize, almost certainly with the connivance, if not the active assistance, of his Roman patrons (p. 440).75 There was also a mildly puritanical streak of self-betterment and self-control in Scipio that appealed strongly to Polybius, who goes out of his way to emphasize how different the moderate, altruistic, brave, generous Scipio was from the common run of upper-class young Romans, many of whom were willing to pay a talent for a boy lover, or three hundred drachmas for a pot of caviar.76

Yet, again, there is something disturbing about this long and uncharacteristic hymn of praise to a patron. How far did Polybius remain objective over Scipio, and the public events with which he and his family were involved? It has been noted that almost all the Roman speeches in the Histories are made by connections of Scipio’s family, not an encouraging sign.77 Once again the ad hominem motif is detectable. Despite his insistence on historical impartiality, his declared contempt for writers who inflate local or personal interests on their own behalf,78 one gets the constant nagging suspicion that Polybius’s grandiose scheme of universal history conceals, at one level, an extended apologia for his own career and the aims of the Achaean League. This does not make him any the less interesting. He knew his Thucydides and Xenophon well, and can hardly have failed to reflect on what he had in common with his two famous predecessors. All three of them spent long years in exile—exile, moreover, that in one way or another brought them into sharp conflict with groups of their own countrymen in power. All three were strongly conservative landowners, at odds with the more radical democrats of their own cities. Like Xenophon, Polybius was a country gentleman who rode, hunted, and had very considerable military experience. Last, all three were conditioned, as historians, by the events that had shaped their lives, even though Thucydides hardly protests his impartiality more than Polybius does, and Polybius’s declared methods of work—his respect for firsthand information, his safeguards on speeches, his care with documents—at times almost verbally echo those of his great Athenian forerunner. Like Thucydides, Polybius was obsessed by the idea of truth; but as has been well observed of him, he was clearly “a man who has persuaded himself of the truth of matters in which he has a strong personal commitment, and is not prepared even to envisage the possibility that there may be another point of view.”79

Polybius spent seventeen years as an official detainee. He seems to have had remarkable freedom of movement, especially when in Scipio’s entourage. Yet “he had come to Italy under a cloud and he stayed on under compulsion.”80 Inevitably, his picture of Roman public life was affected by his ambiguous status, mostly toward discretion. He tells us nothing about the murderous rivalries between the great Roman families, the sulphurous lawsuits, the scandals, the corruption. This kind of tactful omission is precisely what we might expect in an ambience where “to disapprove of Rome was to perish.”81 He can analyze Rome’s rise to world domination, but he cannot afford either to query her motives or to challenge the rise itself, much less take apart the machinery of government or scrutinize the internecine power struggles he witnessed. He also had to take it as axiomatic, whatever evidence to the contrary he might observe, that the ruling class was firmly in control both of its own lower orders and of the Italian allies.82 As a result his Roman characters tend to be one-dimensional, or at best seen out of their social context (Cato is a nice instance: all the old curmudgeon’s jokes at Polybius’s expense are quoted, but we hear not a word about his endless feuding and litigation),83 while the single theme of imperial progress eclipses all else. Though individuals may be criticized, this policy is never questioned.

What Polybius was up against can be judged by his fate and that of his fellow Achaeans. It was not until 150, after at least four previous petitions had been refused (the first written decision declared that “we do not consider it in the best interests either of the Romans or of your own peoples that these men should return home,” a perennial bromide),84 that Scipio, whose influence was now at its height, persuaded the Senate to rescind the deportation order. By this time no more than three hundred of the original thousand were left alive. Yet despite all this the proposal still encountered fierce opposition. Polybius, relying on his privileged status, pressed for reinstatement with all former honors. Cato the Censor, who had supported the Achaeans’ plea to go home, with jovial asides about turning them over to the Greek undertakers, told Polybius, twinkling (but the joke had its sharp edge), that he ought to learn from Odysseus, and not go back into the Cyclops’ cave to retrieve the hat and belt he had left behind.85 Clearly Polybius, however influential his friends, could not count on Rome beyond a certain point. Even after his release he remained, like any Roman client, under serious obligations to his patron,86 and in reading his work it is important to bear in mind that “he was never completely free to express his real opinions.”87

Interestingly, he was in no hurry to return home after his release; and even after he had done so, he was soon back in the company of his Roman friends once more. Probably in 150 he accompanied Scipio to Spain and North Africa, where he interviewed the aged Numidian ruler Masinissa for his recollections of Hannibal (“Very avaricious”).88 Scipio also seems at some point to have sent him on an exploratory voyage round the coast of northwest Africa.89 Back in Achaea he ran into a wave of rabid separatism that was fast moving toward a direct confrontation with Rome (pp. 448 ff.). His appeals for peace and unanimity fell on deaf ears, and (one suspects) his own position as, in effect, Rome’s protégé did not make him popular with the nationalists of the day. Thus when (149) he received an official invitation to proceed to North Africa “as there was need of him for public service,” he accepted with alacrity, and the Achaeans voted to send him.90 If he foresaw the coming disaster—and he must have been blind if he failed to—he probably figured that he would rather be elsewhere when it happened.

Though this first journey proved abortive—he turned back from Corcyra because he mistakenly thought the war was over—Polybius in 146 stood with Scipio and watched Carthage burn, duly recording for posterity his patron’s prescient obiter dicta about Rome one day suffering a like fate, his noble tears over the transience of empire.91 That same year the Achaean League went down fighting Rome’s legions, and Corinth, at the Senate’s express command, was sacked and razed to the ground.92 Polybius returned to Greece as Rome’s postwar liaison officer, in time to see the looted art treasures stacked outside Corinth for removal to Italy, while soldiers sat playing draughts on priceless paintings.93 The League had been abolished: Polybius’s new role was that of a Roman commissioner—commissar, almost—who had, in effect, to sell the new regime to the various individual cities, regulate the relations between them, and in general make the transitional period as smooth as possible.94

Despite the role he performed, it is clear that he found Rome’s actions in 146 both alarming and unpalatable, and tried, in the Histories, to convey to his masters something of what the Greeks felt about this new fire-and-sword policy. Two of the four types of Greek reaction to the destruction of Carthage that he records—tucked away tactfully between others that acknowledge the logic or necessity of Rome’s “final solution,” in terms of imperial self-defense or legitimate coercion95—speak of ruthlessness, treachery, and the lust for power (philarchia).96 About Corinth, on the other hand, he kept discreetly quiet. He had already made his feelings on terrorism very clear when discussing Philip V’s destruction of Thermon in Aetolia, and his Greek readers would not be slow to apply the lesson for themselves:97

Violent and gratuitous destruction of temples, statues, and all such gear, since it offers absolutely no advantage to one’s own side in a war, and does nothing to cripple the enemy, can only be described as the act of a deranged mind and attitude. Decent men should not make war on the ignorant and wrongheaded with a view to stamping them out and exterminating them, but should rather aim to correct and remove their mistakes. Nor should they lump the innocent and the guilty together, but rather treat those they regard as guilty with the same merciful compassion that they extend to the innocent. Wrongdoing as an instrument of terrorization, to coerce unwilling subjects, belongs to the tyrant, who hates his people as much as they hate him; but a king’s business is to treat everyone well, to win men’s love by his humane and generous conduct, and thus to rule and preside with the consent of those he governs.

Fine words; but they stand in piquant contrast to the latter-day career of their author, whose actions, if not his private thoughts, were dictated by a bitter consciousness of the inevitability of Roman overlordship.98

Polybius might have been treated as a traitor by his fellow countrymen, but the fait accompli of defeat made him rather appear in the guise of a savior. His services to Achaea in the difficult years after 146 were gratefully recognized—not only by the pro-Roman aristocratic government—with statues and other marks of honor. He did his job honorably, refusing all gifts. One inscription claimed that if Greece had followed Polybius’s advice, she would never have fallen; and that, having fallen, it was only through his aid that she survived. In his own city of Megalopolis it was written as a tribute that “he had been the Romans’ ally, and had stayed their wrath against Greece.”99 Those words alone show how radically the Greek spirit had changed, even since the days of Aratus and Cleomenes. The nationalists who had died fighting for Achaea, playing their last desperate hope (and suspected by the bien-pensant of revolutionary aims), get little sympathy from Polybius—or, one suspects, from the citizens who had to live with the consequences of their failure. This is what really arouses Polybius’s anger. Their aims, he declared bitterly, had been unrealistic; they did not understand Roman methods, they completely misjudged the situation, and because of this obdurate, indeed criminal, stupidity, they had brought disaster on themselves and their people.100

The dream of independence was ended at last: it was not to be fully renewed for another two millennia and more. Polybius himself lived on for nearly thirty years after the sack of Corinth, years mostly spent working on his magnum opus. He still traveled. He visited (145 or later?) the Alexandria of Ptolemy VIII, nicknamed Physkōn, “Potbelly,” “Bladder” (p. 538), and, predictably, found it an unpleasant sink of gross luxury.101 He may have accompanied Scipio during the siege of Numantia in Spain (133).102 He also at some point apparently traced Hannibal’s route through the Alps. He visited Locri in southern Italy on several occasions, and claimed to have won the Locrians exemption from service in Rome’s Spanish and Dalmatian campaigns.103 But for the most part he probably worked and hunted to a vigorous old age at home in Arcadia. He is said to have died at eighty-two, of a fall from his horse, returning from a day’s excursion in the countryside.104

What kind of a history would such a man create, looking back over his long and strangely fragmented life? How far, and in what way, would his views have changed between his highly politicized youth in Achaea and his Romanized old age? We have already seen his bias at work: how far can we trust him over the events he describes? And, perhaps most important, how literally are we to take his endless explanatory asides, telling us what his intentions are, what he regards as the function of a historian, the value of history? Why so much self-justification? And if, as Buffon insisted, the style reveals the man, what are we to make of his prose, no bad place to start in any evaluation of a historian? The first thing one notices is his terrible weakness for abstractions, a habit that Orwell regarded as a telltale symptom in the historical propagandist anxious to camouflage a bad case. The sentences are long, clumsy, and overloaded: Polybius may be trying to emulate the thorny complexities of Thucydides, but what he actually conveys has been well described as “the flat and prosy verbosity of a government department.”105 His grasp of periodic structure is rudimentary, and his bureaucratic muddiness has been compared with the style current in the Hellenistic chanceries, what German scholars refer to as his Kanzleisprache.106

He nowhere describes himself as a realist (though the pursuit of pragmatikē historia strongly implies it); he does not need to. His vision is flat, relentlessly two-dimensional; he never thinks of himself as an artist. If he was aware of the way in which imaginative Roman writers were assimilating Greek models to create a new kind of literature, he gives no signs of it. He is a politician setting the record straight to his own satisfaction, in the wearily portentous prose of his kind. He is not only deficient in creative imagination himself—a trait he shares with Xenophon, and one that offers certain advantages to the modern scholar evaluating his evidence—but also, we find, irritably suspicious of those historians who possess it, on the grounds (not entirely mistaken grounds, either) that they will produce a distorted, romantic version of events. He himself, on the other hand, is prickly because he is using these same events to justify himself. He was not exactly a quisling:107 despite his friendship with Scipio—whose equal he would have considered himself, socially if not in wealth108—he must have deeply resented the destruction of his career and country, his unjust deportation, his uneasy client status.

Yet there was ambivalence in his attitude, and more than a touch of the pragmatic collabo about him. He belonged to the ruling class; he had held high office. As a member of the property-owning elite he could not fail, at one level, to sympathize with the aims of Roman government, which were, inevitably, slanted in favor of wealthy upper-class provincials, and against insurrection, whether national or social.109 He had a vested interest, after the fact, in Roman rule, and the scholar who labeled his role in Achaea from 146 as that of a “Roman commissar” was not exaggerating.110 As Momigliano says, he “paved the way for the other Greek intellectuals who accepted Roman rule and collaborated with it.”111 He could justify this role only by working to limit Rome’s growing appetite for unilateral exploitation (uncomfortably apparent after 146), her increasing use of force to maintain her supremacy—and, to a lesser extent, by appointing himself the interpreter of the New Order to his fellow Greeks. When we read him we should always remember that he is explaining Rome to a Greek audience; though he keeps one eye on his Roman readers too, he remains above all Rome’s spokesman, “interpreting Rome to Greece, explaining that the empire had come to stay and could not be resisted, and indicating that this was such a vast historical design that it absolved his own compatriots from any slur of failure or impotence.”112

The Stoic philosopher Panaetius, a Greek from Rhodes, similarly tried to reconcile Greeks to Roman rule: no accident that Panaetius too was an intimate of Scipio, that they and Polybius had long discussions together on the Roman constitution.113 (The logical end of this trend was reached by another Greek thinker, Poseidonius of Apamea, who identified the Roman empire with the Stoic world state.) This matter of the constitution, discussed at length in Book 6, is revealing. Behind it lies the belief (which has something to be said for it) that a nation’s destiny is inseparable from its system of government. On the other hand, Polybius’s actual analysis of that system is, to put it mildly, bizarre. He praises Rome for her supposed “mixed constitution,” an adaptation of Plato’s and Aristotle’s blend of monarchy (the consuls), aristocracy (the Senate), and democracy (the popular or plebeian element).114 Such a mixed constitution was conceived to be the evolutionary climax of a process that had begun with Romulus and his successors, continuing by way of Tarquinius Superbus, the tyrant, to aristocratic rule and the oligarchy of the decemvirate.115 It was also thought to have saved Rome, about the mid-fifth century, from the eternal repetitive sequence (anakyklōsis) of kingship/tyranny-aristocracy/oligarchy-democracy/ochlocracy.116 This ingenious fantasy—a classic example of what happens when literary authorities, however irrelevant, are preferred to direct observation, however convenient—was finally nailed for the nonsense it was only by Mommsen.117

It is clear from this, and indeed has often been noted, that for a man who spent seventeen years among Roman statesmen, in a crucial period of Roman history,118 Polybius is surprisingly obtuse about how the Roman system actually worked. His thinking, both practical and theoretical, never really breaks loose from its Greek conditioning. His view of Rome’s imperial activities overseas is colored by the innate assumption that what he was dealing with was something very much akin to a Hellenistic monarchy. The niceties of provincial government through magistrates either eluded or failed to impress him: perhaps he saw the whole thing as an elaborate sham.119 He, of all men, should have understood the subtleties of Roman political life, of patronage and clientship, the dominant role of the Roman nobility, “the nuances of public life.”120 Perhaps in his heart of hearts he did; perhaps it was all too close to the bone for comfort. But perhaps, too, the theoretical model he set up was designed, by way of comfort or parochialism, for Greek readers, who would instantly recognize Aristotelian theory when they saw it.121 Whatever the influence on him of the Scipionic circle, his intellectual premises remained firmly set in a Greek mold,122 and it seems all too likely that, like most educated Greeks, he still privately regarded the Romans as semibarbarians. He may even have had the Achaean League in mind as a model for Rome: it was certainly his ideal.123

Thus despite his claims to universalism, Polybius remained at heart a Peloponnesian Greek, who constantly exaggerated the importance both of the Leagues and of Macedonia in the Mediterranean at large (and per contra, found it hard to forgive Timaeus for doing precisely the same with Sicily and Magna Graecia). He attacked the habit of self-promoting parochialism in others, but was far from immune from it himself. This is not entirely surprising. Polybius was no intellectual in the formal sense: his ideas about religion were muddled; his philosophical concepts, thirdhand commonplaces. As a result, his approach to history was both confident and simpliste. Facts were facts, and could, with proper care, be retrieved, along with their causes.124 Epistemological doubts never assailed him:125 like Ranke, he sought to recover the past wie es eigentlich gewesen sei, in his own words “to record with complete fidelity what was actually said and done, however banal it might be.”126 The aim was utilitarian: past exempla would enlighten future readers, particularly statesmen.127

Polybius’s limitations can be seen as an inevitable consequence of his upbringing. His formative years had been spent in the narrow, feuding environment of the Leagues of central Greece: nor was it so very long since Arcadia, Aetolia, and Achaea had been among the most backward, primitive communities south of Thessaly. Polybius made a hero out of that rabid local nationalist Philopoemen (though he was not above criticizing him on occasion);128 his virulent distaste for the Spartan king Cleomenes was not only political but social, Cleomenes in his view—generally shared at the time—being a dangerous would-be subverter of the established order.129 He had all of Thucydides’ admiration for success, and Xenophon’s self-alignment with the rural aristocracy. When, in his early thirties, he was forcibly removed to Rome, these various traits must have made him, for all his resentment, as susceptible to Rome’s powerful allure as a nineteenth-century Fiji Islander to the measles. He tries to suggest that the young Scipio hero-worshipped him;130 elsewhere he makes it clear (what no one could doubt) that it was really the other way round.131 Whether he wholly approved of the policies that Scipio was called upon to implement is, as we have seen, quite another matter. In any case the process of assimilation and change must have been traumatic, and there are signs that Polybius never fully recovered from it. The efficiency, power, order, and discipline that he found in Roman government and Roman military affairs appealed to him in the way that the administration of British India appealed to Kipling. Yet, like Kipling again, he had his moments of doubt. How, he must have asked himself, did Scipio’s sack of Numantia differ from the destruction of Corinth or Carthage? He also seems to have foreseen the convulsions of the late Republic, which, like Cato and others, he saw as the necessary outcome to moral decay engendered by long prosperity.132 Worse, despite all the manifest benefits to his own class from a clientela-like relationship to the dominant power, despite his personal position of precarious privilege, his Greekness could never quite swallow the plain fact of defeat. Here was where fate stepped in. The concept of Tyche took responsibility off his, and his countrymen’s, shoulders. His thinking here is blurred, and small wonder. Tyche smiled on the Romans because of their achievements; their achievements were due to Tyche. The argument achieves its own anakyklōsis.

Within the definable limits of his prejudices, Polybius is, by and large, a conscientious historian. In his speeches he follows the Thucydidean example of trying to get as near as possible to the gist of what was actually said.133 He stresses the historian’s need for practical political experience, for topographical autopsy.134 He worked hard to get his facts right, even if he did not always follow his own precepts. He talked to survivors; he made use of memoranda specially prepared by himself or others; he consulted archives and inscriptions;135 he tried to take the long view. Ultimately he is best on military action, straight narrative, the day-to-day minutiae of diplomacy. His character analyses, though they often make shrewd points, are parti pris and too prone to great-man motivation. His attacks on various fellow historians would carry more weight were he not guilty of most of the same faults himself. He dismisses Timaeus as a niggling fault-finder, in two long and vicious digressions in which he himself niggles and carps with the best of them.136 The animus here is that of the experienced statesman and soldier faced with a typical intellectual of the day, remote from practical affairs, dependent on books rather than experience, and liable to substitute rhetoric for passion. Yet, Timaeus might have retorted, was not Polybius’s own description of the Roman constitution the merest Aristotelian mishmash? Did he not on occasion have recourse to books, with erroneous results, instead of using his own eyes when that would have been easy enough—for example, in his description of a Roman military camp?137

His underlying motives are sometimes concealed. It seems pretty clear that whatever he alleges against Timaeus, the strongest animus he felt was caused by natural jealousy of Timaeus’s huge success.138 Similarly, he criticizes Phylarchus for overdramatized sensationalism, in particular for his harrowing descriptions of how half-naked women and children were led off into slavery, sobbing and wailing, after a town’s capture.139 But what he really resented was Phylarchus’s sympathetic portrayal of Cleomenes. Once again, too, pot is calling kettle black, since Polybius himself was quite capable of pulling out the rhetorical stops when it suited him. Good examples are the mutiny in Alexandria after Ptolemy V’s accession; Hasdrubal’s surrender, cursed by his comrades, reproached by his wife, at the fall of Carthage; and the long elegiac lament over Greece’s downfall and ruin—fair Greece, sad relic—which he witnessed in 146.140 He must rationalize his own actions by making Rome a more than human force, and duly does so; but he is also not above defending his own position as a historian by denigrating the competition with whatever criticism comes to hand.

The fact that Polybius never entirely lost his Greek sense of local, Hellenocentric superiority, even after seventeen years of watching Greece’s nemesis in action at close quarters—let alone with Alexander’s example to ponder—tells us more about Greek irredentism in general than it does about Polybius qua historian. At least Polybius grasped the concept of universalism—or at any rate of Mediterraneanism, which in the Graeco-Roman world tended to be regarded as the same thing: one reason for the failure of the Seleucid empire, too much westward squabbling while the eastern pot boiled over—and left us an invaluable narrative, based as much on personal experience as on research, of the events accompanying Rome’s rise to supreme power in the ancient world. We may challenge his general explanations for this phenomenon, we may pick holes in his much-vaunted objectivity, we may charge him with personal prejudice or camouflaged self-exculpation, and all these criticisms will have considerable force. Yet in the last resort his faults are venial, and for long stretches forgotten both in our sympathy for his protracted ordeal (however successfully he conformed to his new world), and in our gratitude for the very existence of his Histories as such. Over the eighty-odd years that he covers he remains our best, and at times our only substantial, source of evidence. Ancient historians, perhaps a stronger breed today than Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who could not bear to read him from cover to cover141—but then Dionysius was more concerned with style than substance—continue to criticize his failings while using his material. Since that is just what Polybius himself did to Phylarchus and Timaeus (whose chronological system of Olympiads he took over), he has no real cause for complaint.