In June 217 the news of Rome’s defeat by Hannibal at Lake Trasimene reached Greece. Philip V of Macedon read the dispatch in eloquent silence at Argos while attending the Nemean Games.1 He showed it only to his Illyrian confidant, the ambitious freebooter Demetrius of Pharos, who had sought refuge at Philip’s court when driven from Illyria by the Romans (p. 296).2 Demetrius instantly advised him to wind up the local war then occupying his attention, and to devote his full energies to the West. This war, known as the Social War or the War of the Allies, had been spluttering on intermittently since 221.3 After Antigonus Doson’s death, the Aetolians saw their support in the Peloponnese crumbling, and felt themselves—not without reason—to be surrounded by enemies, most notably Macedonia and the Achaean League. Fighters by nature, they decided to take the initiative: vigorous raids were carried out against Messenia and a whole string of Achaean-held frontier posts. Messenia appealed to the Achaean League; both the League and Philip—in his capacity as heir to the leadership of Doson’s Greek alliance (symmachia: above, pp. 260–61)—declared war on Aetolia, with lavish promises that the cities under Aetolian control would, on liberation, enjoy their ancestral laws and constitutions, ungarrisoned, free, and tributeless (aphorologētoi). It was the Roman Flamininus who ensured maximum publicity for this tempting package deal (below, p. 311); but he almost certainly borrowed the idea from Philip.

The news of Cleomenes’ death led to yet another royalist coup in Sparta (ca. 219): the ephors were murdered, a legitimate Agiad was deposed, and the new king, Lycurgus, allied himself with the Aetolians. A Putsch in Messene about 219 seems to have toppled the oligarchic regime there, which had been friendly to the Aetolians, and to have replaced it with a populist, pro-Achaean government.4 Yet another installment of the Graeco-Macedonian ronde was now under way. In the campaigns that followed, Philip and his allies consistently outfought and outmaneuvered their opponents. Discipline in the Macedonian army was strict.5 Philip’s speed, energy, and dash,6 his strategical flair, his use of siege equipment, all provoked comparisons with Alexander the Great7—with whom, on rather flimsy evidence, he claimed relationship.8 Like Alexander, too (or indeed any new Macedonian monarch), he had lost no time in purging his predecessor’s overly influential advisers, partly with the help of Aratus and Demetrius of Pharos.9 Like Philip II, he had an inordinate passion for wine and women; his relationship with Aratus did not, characteristically, stop him seducing the wife of Aratus’s ineffectual son—whose lover, equally characteristically, he had also been.10 His prestige was now enormous: dedications were made to him; he was even known as the "darling [erōmenos] of Hellas,”11 a title to be recalled in irony when later he earned a reputation as a bloody butcher.

Soon after the incident at the Nemean Games, peace negotiations took place at Naupactus, on the north coast of the Corinthian Gulf.12 Philip had clearly found Demetrius’s advice attractive,13 and that shrewd politician Aratus was only too glad to pick up what he could at the conference table. An armistice was concluded on the basis of the status quo. But during the talks the speech that stuck in everyone’s mind—if we are to believe Polybius—was that made by the Aetolian negotiator, Agelaus, who had earlier raided Achaea with the Illyrians,14 but was now sounding a warning of a very different sort:15 “If it’s action you want, then look to the west, pay heed to the war in Italy. . . . For if you wait till these clouds, now gathering in the west, come to rest in Greece, I am mortally concerned lest we may, every one of us, find these truces and wars, and all such childish games that we now play against each other, so abruptly cut short that we shall find ourselves praying the gods to leave us at least this power—to fight and make peace with each other when we please, in short, to have control over our own disputes.”

While flattering Philip’s warlike ambitions, the speech—if genuine, which is doubtful16—also carried an implicit plea to the young Macedonian king not to rush impetuously into a conflict with Rome. Greek unity was more important. Despite Polybius, it is unlikely that such a warning was needed—yet. Philip may have been headstrong and ambitious, with the temper of his ancestor Pyrrhus,17 but he had a very firm grasp on logistical realities. To attempt an invasion of Italy with no harbor from which to operate, and while Macedonia’s own frontiers were still threatened, would be suicidal.18 Even after Cannae, when the temptation was far greater,19 such an undertaking still remained, in essence, an impractical dream. War fever and hysteria will have lent the threat a kind of spurious reality at the time, and this shows clearly in our sources. Just what Agelaus really said at Naupactus we cannot determine, but it is unlikely to have been as prescient as Polybius claims. Even if he did not fabricate it in toto to fit his theory of history, this speech remains to a great extent the product of historicizing hindsight.

The occasion, at least, was appropriate enough. Naupactus was the last peace settlement that the Greeks ever made without Roman participation: little more than twenty years later the Roman Flamininus (see p. 417), despite his philhellene pretensions, was laying down the law for Greeks and Macedonians as though he were a paterfamilias and they the fractious, ill-behaved children that at times they so uncomfortably resembled.20 Like most momentous changes, this one came about by a series of apparent accidents. Yet behind the events lay an ineluctable pattern: the fatal inability of the Greeks to unite in common action, the quarrelsomeness that Rome learned, all too well, how to exploit; the ambition and greed (commercial no less than military) of the great senatorial families, the alluring wealth of Egypt and Asia; the awesome superiority of the Roman military machine, the resilience in the face of disaster that enabled Rome to survive, not only Trasimene, but Cannae and the Trebbia, and still, ultimately, to thrash to Hannibal (202), to burn Carthage (146: above, p. 279). Despite her own serious internal conflicts, Rome was strong and united in a way that Greek separatism could never match. If Agelaus ever really called on his fellow Greeks to close ranks against the threat from the west, the cry fell on deaf ears. Where was Antiochus, where were the Achaeans, when in 197 Philip V of Macedon went down to defeat at Cynoscephalae (p. 310)?

But this is to anticipate. In 221 the new young monarchs who had come to the thrones of all three Successor kingdoms—Antiochus III, Ptolemy IV Philopator, Philip V—had other problems on their minds. That Rome, a still largely unknown power, had in 229/8 become, briefly, involved in Illyria was regarded as a matter of small importance (above, pp. 253 ff.). Even Rome’s so-called First Macedonian War, which followed (below, pp. 297 ff.), “misnamed what was basically a contest among Hellenes and Macedonians, a revival of the Social War, a reflection of Hellenistic politics.”21 Antiochus and Ptolemy both inherited the endless ongoing quarrel over their Syrian frontier; Antiochus, in addition, was plagued, throughout his unwieldy empire, with secessions and would-be usurpers, and Ptolemy (at least from 207, and probably much earlier) had to deal with a series of dangerous native insurrections and the loss of the Thebaid. Macedonia was at least as much preoccupied with the nagging problem of the Greek leagues as with Illyria. Yet before long all three of them—even Antiochus, whose interests, on the face of it, lay in a quite different direction—had become dangerously embroiled in the Roman issue.

It will be convenient, in fact, to begin with Antiochus, whose driving ambition, probably from the moment he ascended the throne, was to restore the lost imperial possessions of his great-great-grandfather, Seleucus I Nicator (above, p. 31). This program aimed, ultimately, at the reconquest of Coele-Syria as far as the gates of Egypt, the repossession of the great eastern satrapies, and firm control not only over the seaports of Asia Minor, but also of the Hellespont itself, and of eastern Thrace on its European side. It is a mark of Antiochus’s stature (and at least some justification of his title, "the Great") that in appearance at least, even if only for a brief period, he succeeded in all these projects. It is worth noting that his most ambitious undertaking, the great expedition to Bactria and India, with its unmistakable echoes of Alexander, bothered the Romans not at all; it was only his comparatively minor campaigns in western Asia Minor and, above all, in Thrace to which they took exception (pp. 304 ff.).

When we consider the troubled realm he inherited, it is surprising that he had as few initial setbacks as he did. (How far even these were due to the supposedly malign and brutal influence of his vizier Hermeias, a Carian Greek in whose assassination the king eventually connived, remains uncertain: Polybius is our sole source for Hermeias’s activities, and his account reeks of hostile propaganda.)22 His general Achaeus, the conqueror of Antiochus Hierax (above, p. 264), and the master mind behind Antiochus’s own accession, continued as a tower of strength in Asia Minor, driving Attalus I back till he held little more than Pergamon itself (spring 222), and overall, Polybius claims, acting “with intelligence and generosity.”23 Having dealt with a major revolt by Molon, his successor as governor of Media (221–220)24—a difficult campaign that got off to a shaky start—Antiochus decided to begin his program by invading Syria; he had no doubt heard, through his intelligence sources, that Egypt was crippled by court intrigue and public unrest. An earlier attempt had never got off the ground (221): this time he launched a major expedition (the Fourth Syrian War, 219–217). The excuses given were the standard ones: Syria and Phoenicia had originally been conquered by Antigonus One-Eye, and promised to Seleucus Nicator after Ipsus in an agreement with Cassander and Lysimachus; Ptolemy Soter, both during the war of 315–311 and at the time of Ipsus, had been, officially, campaigning for Seleucus rather than on his own account.25

Antiochus got off to a good start. He captured Seleucia-in-Pieria, thus winning back a major port on the eastern Mediterranean littoral (above, p. 263).26 Tyre and Ptolemaïs-Ake surrendered to him: the road through Palestine to Egypt lay open. Had he been Alexander he would have followed it—probably with success, since Ptolemy’s defenses were in no sort of preparation.27 But he preferred a more cautious and methodical approach, consolidating his position in Galilee and Samaria.28 Meanwhile Ptolemy’s diplomats stalled him with peace talks—chiefly remarkable for the tangled web of claims and counterclaims over Coele-Syria that Polybius’s account of them reveals29—while a large army was got together by the king’s Greek adviser Sosibius. Sosibius not only put these troops through a rigorous training program under professional Greek officers (a step that paid off handsomely); he also took the novel step of enrolling no less than thirty thousand native Egyptians as hoplites. Advantageous in the immediate emergency, this decision was, in the long run, to destablize the regime more than any external threat.30

Between leisurely negotiations and Antiochus’s own weakness for local siege warfare, Ptolemy held up the Seleucid invasion until the summer of 217. Then, at the head of fifty-five thousand men, and accompanied by his young sister Arsinoë III,31 he took the field in person, to face Antiochus’s army, now sixty-eight thousand strong, at Raphia, in Palestine, just beyond the Egyptian frontier.32 It was the biggest formal battle since Ipsus, which it also resembled in another way: Antiochus, like Demetrius the Besieger before him, shattered the enemy’s left wing (his combination of cavalry and elephants proved irresistible);33 but—again like Demetrius—he could not resist pursuing his advantage, so that Ptolemy’s commanders were able to organize a counterattack and shatter the Seleucid phalanx while its general was still on his death-or-glory charge.34

Resounding triumph though it was—Coele-Syria was safe, and Egypt relieved of the threat of invasion—Raphia brought little good to the victors, and some unlooked-for troubles as well.35 Ptolemy IV, despite recent attempts to credit him with an active foreign policy,36 was clearly an indolent character, dominated to a great extent by his advisers and womenfolk, if not the complete sensual fribble portrayed by Polybius.37 There is an interesting contrast, in the latter’s account, between Sosibius’s energetic preparations, which brought victory at Raphia,38 and the king’s dilatory disinclination to follow that victory up, ascribed by Polybius to his urge to get back to the fleshpots of Alexandria—even though he then admits that Ptolemy spent a further three months settling affairs in Coele-Syria and Phoenicia.39 His concern for family affairs also extended to acquiescence in the murder of most of his close relatives, including his mother.40 At all events, having won the battle he was quite happy to settle for the status quo; he even let Antiochus keep the naval base of Seleucia-in-Pieria. Coele-Syria, at least, stayed in Ptolemaic hands for almost another two decades. Ptolemy also now married his sister Arsinoë (October 217), and the two received a cult as the Father-Loving Gods (Theoi Philopatores).41 But his Egyptian troops had tasted blood, and sensed their own power: on the domestic front the king had won what was to prove an expensive victory.42

In this connection there may have been more pressing motives than self-indulgence for the terms he allowed Antiochus. A fall in population and a shrinkage of overseas trade had brought about so acute a shortage of silver in Egypt that the silver currency was debased; a bronze coinage was introduced during the reign of Ptolemy III, and in 210, only seven years after Raphia—and Trasimene—silver seems to have been abandoned altogether as Ptolemaic Egypt’s standard currency.43 In the circumstances it would be understandable if Ptolemy balked at hiring the extra mercenaries needed to pursue an aggressive foreign policy; financial considerations may similarly have dictated the enrollment of Egyptian troops at cut-price rates. Raphia doubtless brought in a fair amount of the plunder that constituted a major source of regular income for any Hellenistic monarch; but after Raphia the supply dried up. The problem is complex;44 it does, however, seem more than likely that events in Egypt now tended to follow a vicious circle. The native troops in Ptolemy’s army stimulated a strong nationalist movement; the nationalists at first restricted themselves to a long, and successful, guerilla campaign, but then rebelled so effectively against the central government that for a long period Upper Egypt achieved total independence under a series of native pharaohs (205–186/5?);45 the loss of Upper Egypt deprived Ptolemy of a substantial proportion of his revenues, besides necessitating an increased army of mercenaries to fend off the constantly marauding rebels; the resultant drain on capital meant a serious cutback in overseas trade, which in turn exacerbated an already difficult economic situation.46

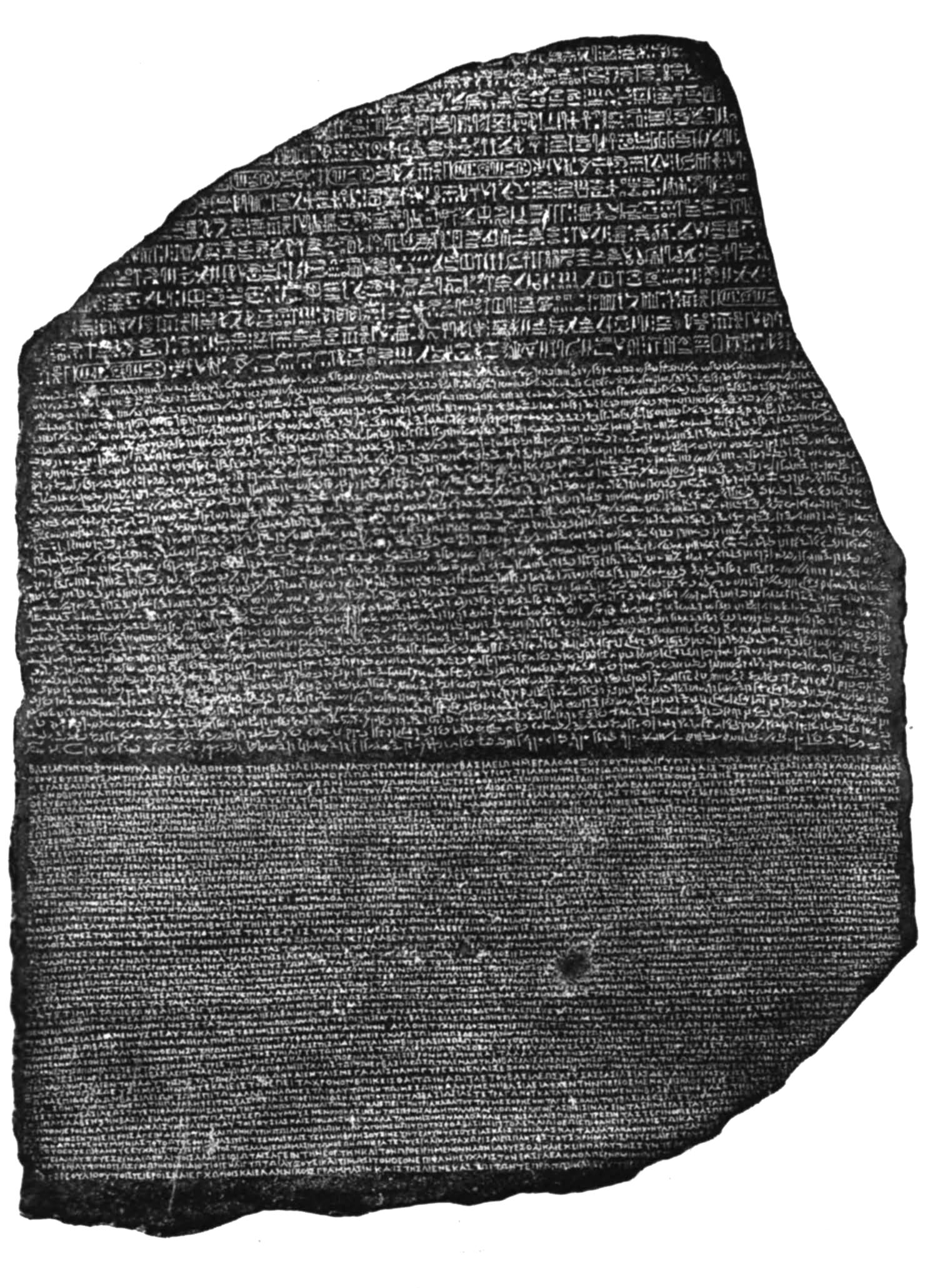

All these factors should be borne in mind when considering Ptolemy’s lackluster foreign policy. It is true that the real deterioration only set in about the time of Philopator’s death, or shortly before (205/4): until then the Ptolemaic empire remained more or less intact. Then came open revolt and anarchy, backed by the native priests, and disrupting administrative communications throughout the kingdom: even the famous elephant-hunting expeditions had to be discontinued (see below, p. 329).47 The Ptolemaic government had worse dangers to face than Antiochus III’s depredations in Coele-Syria, and the equally conciliatory treaty made with him after the Fifth Syrian War reflects this all too clearly (below, p. 305). The surviving honorific decrees from Canopus (March 238) and Memphis (March 196) reveal an increasing effort to conciliate the powerful native priesthood, to create some kind of acceptable common ideology of power for Greek rulers and privileged Egyptians alike.48 But the economic crisis led, inevitably, to harsher taxation and greater bureaucratic stringency, thus giving fresh animus, and further recruits, to the nationalist movement.49

Three years before Antiochus’s defeat in Syria (220), his hitherto loyal commander (and maternal uncle) Achaeus50—presumably encouraged to play his own hand, if not by Molon’s example, at least by his own reconquest of Asia Minor—had proclaimed himself king, and assumed the diadem.51 However, his mercenary army, recognizing a no-win situation when they saw one, refused to follow him to Antioch,52 and he ended up as a freebooter in the Anatolian highlands: Antiochus judged, correctly, that Achacus and Attalus of Pergamon, old opponents already, would keep each other busy for a year or two. In 216 Antiochus moved back into Asia Minor himself, blockaded Achaeus in Sardis, and in 213 caught him trying to escape. The pretender was mutilated and his corpse crucified, an Achaemenid practice that suggests Antiochus was rehearsing his chosen role as Great King of Asia.53 It also made an example that discouraged civil war in the Seleucid domains for the next fifty years.

Antiochus now was ready to move east, on an extraordinary campaign—as much propaganda as actual conquest—that lasted seven years (212–205), was impressive rather than substantial, and came to be known as his anabasis. Its object was the recovery, or, failing that, the amicable co-option, of lost territories in the upper satrapies, including Bactria and Parthia, both now ruled by independent dynasts. The situation in the satrapies of southern Iran—Carmania, Gedrosia, Drangiana—is unknown, but in all likelihood they too had seceded. Antiochus in 212 can have been sure of very little beyond Persis (Parsa) and Media. Yet what he planned was to win back control over all territories to which Seleucus Nicator had, however briefly, laid claim.54 Now he was looking eastward, as far as the Indian satrapies long relinquished to the Mauryan Chandragupta (above, p. 29); but later, as we shall see, he also moved on disputed territory in Asia Minor, even in Thrace, simply and solely because the founder of his dynasty had been there before him.55

There may, again, have been economic considerations behind the anabasis: Rostovtzeff plausibly suggested that one reason for Antiochus’s pressing interest in the eastern satrapies was the need to regain access to the gold mines of Siberia and India via the Bactrian caravan routes.56 Be this as it may, the dominant impetus throughout was, beyond any doubt, provided by Antiochus’s passionate dynastic dream, his determination to restore the Seleucid empire in its full and pristine glory. He had at his accession found a realm greatly weakened by territorial losses and internal rivalries. In eleven years—years of stress and maturation—he had suppressed two major rebellions (those of Molon and Achaeus), and recovered Media, Persis, Susiana, and Babylon, not to mention large areas of western Asia Minor. His only failure had been in Phoenicia and Coele-Syria (217). Now he was ready to assault the eastern satrapies.57 Having first secured Armenia58—he had taken care of Media Atropatene (mod. Azerbaijan) as early as 22059—he marched east into Media, where he spent the years 211 and 210 assembling and preparing his army;60 he also raised four thousand talents to pay his troops by taking over the accumulated treasures of the great temple in Ecbatana.

In 209 he was ready, at last, to set out on his anabasis proper: the intimidating news of his massive preparations had clearly traveled ahead of him, as perhaps was his intention. Arsaces II of Parthia came to terms with him.61 After besieging the Graeco-Bactrian king Euthydemus in Zariaspa (mod. Balkh) for two years (208–206), he made a deal with him too: Euthydemus convinced him that they both had more to fear from incursions by nomads than from one another.62 He crossed the Hindu Kush, as Alexander had done, signed a treaty of friendship with a local Indian ruler named Subhagasena (Sophagasenus)—perhaps, inter alia, to encourage trade63—and returned home by way of Arachosia, Drangiana, and the Persian Gulf (206–205).64 He also found time for an expedition against the Gerrhaean Arabs, who purchased their freedom with tribute in cash and spices.65 Antiochus came back to Seleucia-on-Tigris the most famous eastern campaigner since Alexander (205), the champion who had restored Seleucid imperial hopes.66 Yet if the propaganda was good, the actual achievement was insubstantial. The eastern satrapies were not in any real sense subdued: what he had acquired there were friendly neighbors, amici in the loose Roman sense, certainly not vassals. The title of Great King, which Antiochus now assumed, or encouraged others to bestow on him,67 was to a great extent wishful thinking. He still had to recover Coele-Syria, the Anatolian coastal cities, and the Hellespontine area; and it was while pursing this part of his dream of empire that he found himself on collision course with Rome (p. 421).

What, meanwhile, of Philip? As we saw earlier, the new young Macedonian king had very soon found himself engaged in two areas: Illyria and central Greece. In Illyria Demetrius of Pharos, once Rome’s protégé in the Dalmatian archipelago (above, p. 254),68 had set himself up as, in effect, the pirate king of the Adriatic, raiding as far afield as Pylos and the Aegean. He also enjoyed Macedonian protection (from ca. 225), through probably not an official alliance. He had contributed troops to Antigonus Doson for the Sellasia campaign:69 for some reason both Antigonus and Philip treated him as a valued adviser (he was, however, probably not quite the catastrophic éminence grise that Polybius tries to make him out).70 Demetrius’s piratical activities contrived to annoy not only the Rhodians, who expelled his squadrons from the Cyclades,71 but also Rome, which had to deal with repeated complaints from Italian traders in the Adriatic, and may have been anxious to protect grain ships from molestation not only by Demetrius, but also by another, equally vigorous Illyrian corsair, Scerdilaidas,72 who at one point had been similarly contracted to Philip, but broke with him in 217 over alleged nonpayment, and thereafter plundered Macedonian shipping as readily as the rest.73

In 219—the same year, we may note, that Hannibal began the siege of Saguntum—Rome took steps to eliminate this nuisance, and Demetrius sought refuge with Philip (above, p. 286),74 who was then preoccupied by his joint campaign with Aratus against the Aetolians (above, pp. 286–88). Demetrius urged peace, arguing in effect that Philip needed more elbowroom to deal with the Illyrian question,75 and with a shrewd eye to his own reestablishment on the Adriatic coast. The result was the treaty of Naupactus (217: above, p. 287). Philip duly moved into southern Illyria, drove out Demetrius’s rival in piracy, Scerdilaidas, and enabled Demetrius himself to recover his fief there.76 Scerdilaidas, with characteristic effrontery, appealed to Rome. A patrol of ten quinqueremes came to investigate. Intervention by Rome was the last thing Philip either wanted or expected at this point, and he at once retreated. But if he was anxious to avoid a showdown, so, clearly, were the Romans.77 There could be no question of using the Illyrian front to counter either Macedonian or Roman plans for imperial expansion, since such plans simply did not exist. Philip had no ambitions, certainly no immediate ambitions, in Italy; he was far more concerned, as subsequent events showed, to stabilize his always volatile western frontier by subjugating all Illyria and establishing a permanent port on the Adriatic.78 If he dreamed, perhaps, of emulating his ancestor Pyrrhus, he will have been well aware, like everyone else, of how that ill-fated venture turned out (above, p. 231). Since Pyrrhus, no other Greek had looked westward.79 That was not fortuitous. As a result, Rome had been left undisturbed to master the whole of southern Italy and Sicily by the end of the First Punic War (above, p. 232).

If Philip had no ambitions in the West, it was equally true that Rome did not envisage serious intervention in the East. But after Philip’s tentative moves toward creating a Macedonian outlet on the Adriatic were blocked by a Roman squadron, he took a step that brought him no substantial advantage, and made him permanently suspect at Rome. In 215, again, apparently, on the advice of Demetrius, he signed a treaty with Hannibal the Carthaginian.80 This carefully vague treaty was, it is obvious, drafted by Carthage. It required Philip to act as an ally of the Carthaginians, if and when called upon in their war against Rome (which he never was), though to do specifically what, if anything, is not made clear. In return, the Carthaginians undertook, if they won the war, to make the Romans abandon their sphere of influence in Illyria in Philip’s favor—small gain, it might be thought, for a most perilous commitment. The implication of a possible second front made good propaganda in Greek Italy, and was calculated to embarrass the Romans, but remained, in practical terms, a chimera.81 At this point the real likelihood of Philip invading Italy was nil, and even when he finally acquired his Adriatic staging post by capturing Lissos (below, p. 298),82 there was no serious concern in Rome, merely a decision to take routine preventive measures. Indeed, the so-called First Macedonian War, which followed (215–205), was remarkable for Rome’s initially lackadaisical attitude: it is not even certain whether a formal declaration of hostilities was made.83

The course of events shows that Philip’s focus of interest continued to be Illyria: an entanglement with Rome was still something he preferred to avoid. The only time that a Roman squadron appeared on the eastern shore of the Adriatic, to defend the cities Philip was harassing in 214, a similar scenario to that in 217/6 promptly played itself out. The young king, taken by surprise, at once withdrew, burning his own fleet of 120 vessels, and retreating over the mountains.84 The Roman commander, Marcus Valerius Laevinus, now stationed his squadron in Illyria, at least for the following winter (214/3), as a safeguard against future raids.85

The Macedonian threat, as always, looked more serious from the viewpoint of the Peloponnese. Aratus in particular was alarmed by Philip’s increasingly independent policy, the professionalism of his army,86 and the greater ruthlessness he had begun to display under Demetrius of Pharos’s influence. (At some point now Rome demanded Demetrius’s surrender: Philip ignored the request.)87 When in 215 civil strife again flared up in Messene, Philip, with an eye to conquest, incited the factions—"government" (stratēgoi, archontes) and “champions of the people” (dēmagōgoi, proestōtes)—against each other.88 Since the oligarchs had been driven out around 219 (above, p. 286), it follows that (unless another countercoup had taken place meanwhile) a moderate democratic regime was now under attack by radical, and probably pro-Aetolian, extremists. Aratus, alerted to what was going on, hurried to the scene, arriving a day after the dēmagōgoi had defeated their opponents in a bloody Putsch, killing more than two hundred of them.

Philip, accompanied by Demetrius of Pharos, asked leave of the victors to sacrifice on Mt. Ithome, and took Aratus and his son along as well. It seems likely, from what followed, that they had a strong armed escort. Polybius, echoed by Plutarch, records a discussion that supposedly took place on the mountain summit, after the sacrifice.89 Demetrius advised Philip to seize Mt. Ithome, saying that whoever held the two horns of the Peloponnese (Ithome and Acrocorinth) controlled the bull. Aratus was horrified by such talk. If Philip could take Ithome and still keep faith with the Messenians—who had, clearly, given him access to the mountain on condition that he respect its territorial integrity—then, Aratus said, he might keep it. An impossible condition, and so meant. Otherwise, his reputation as an oath breaker would neutralize any immediate advantage that possession of the citadel might offer. Grumbling, Philip conceded the point—for the moment. His abortive meddling in the affairs of Messene had resulted in much bloodshed, but little success.90

He soon, however—perhaps irritated with himself for having given in to Aratus, and, more immediately, by the loss of his fleet—began to ravage the Messenian countryside “as though motivated by passion rather than reason.”91 This may have been his frustrated reaction to a full-scale, but unsuccessful, assault on Ithome led by Demetrius of Pharos, who got himself killed during the action (215).92 From being the “darling of the Greeks” at his accession (above, p. 287),93 Philip came very soon to be feared as a wild, cruel, and politically unpredictable adventurer.94 He and Aratus from then on had little use for each other; and though Achaean propaganda must have painted Philip in progressively more lurid colors, it did not have to invent, ex nihilo, his choleric temper, unruly physical appetites, and weakness for impromptu massacres. It is an index of the new atmosphere prevalent after the treaty with Carthage that when Aratus finally died, in 213, of what sounds like consumption, Philip was widely believed to have had him poisoned.95

For the next two years (213–212), consistently with his policy, Philip kept up his remorseless pressure on the cities of Illyria. To begin with, while he repaired his naval losses, and to avoid unnecessary provocation of Rome, he was careful to stay clear of the coast, where Laevinus, the Roman commander, was now firmly in control of key points such as Dyrrhachium, Apollonia, and Corcyra (which from 213 became his naval base).96 Instead he attacked the hinterland, driving north and cutting deep into Scerdilaidas’s territory.97 It was only then that he made his successful descent on Lissos (above, p. 297), and thus established himself on the Adriatic. So far the Romans had largely ignored his activities; but now—though fears of a Macedonian invasion of Italy can confidently be discounted as, at best, free-floating Roman hysteria that found its way into our annalistic sources98—a situation had arisen in which a first-class power, rather than mere local chieftains and pirates, was now able to menace the trade routes of the southern Adriatic.99 More positive measures were called for.

The Romans, casting around for allies of their own who could deal with this situation, picked, faute de mieux, the Aetolians (212/11): arguably a mistake. The treaty now made between them—the oldest original Roman treaty surviving, and the first document illustrating Rome’s relations with the Greek world—stipulated that Rome would restrict herself to removable booty (a point that Flamininus and his men doubtless recalled later when, with philhellenist zeal, they raided the country for works of art), while Aetolia would get any territorial concessions that might be going.100 The Romans prudently set Corcyra as the northern boundary for this arrangement: they knew the kind of allies they were dealing with, and had no wish to see further potential corsairs preying on shipping in the sea lanes between Greece and Italy.101 The proper function of the Aetolians was to distract Philip. Unfortunately, they overdid it, proving so unbelievably brutal in their habits—the Romans, too, got a bad reputation for atrocities102—that the effect was to create a rapprochement between Philip and the Achaean League.

The relationship, however, being bred of necessity, remained cool. For a long time Aratus’s son (with all the nervous irritation of a cuckolded ex-lover) kept the Macedonian at arm’s length: when we remember Philip’s conduct in Messenia it is not hard to see why. The course of the war between 211 and 208 is confused. Sporadic fighting took place all over and around Greece: in Illyria, Thrace, Thessaly, Acarnania. Philip still could not face the Roman fleet; he did better on land, driving the Aetolians back from Thessaly—an area nominally independent, in fact very much under Macedonian control103—and making short work of an incursion by Attalus of Pergamon (his sole appearance in Greece), who had joined the Roman-Aetolian coalition, and in 209 was actually appointed Aetolian stratēgos.104 Philopoemen, the Achaean League’s general, leading brigades that he had spent some time reorganizing and training, crushed a resurgent Spartan army at Mantinea (207), after which Sparta took no further part in the fighting—though it was not long, as we shall see (p. 302), before her new king made his presence felt in the Peloponnese. Philip was called back to Macedonia, and Attalus to Pergamon, by barbarian invasions.105 Though Laevinus’s successor, Galba, soon earned some notoriety for his Aetolian-style cruelties,106 Rome, having lost interest in these internal squabbles, left the Aetolians to get on with the war from now on.107

This they very soon tired of doing without adequate support. In 206/5 they broke their treaty with Rome and made a separate peace with Philip, which gave him back all he had lost.108 (The previous year he had sacked the Aetolian capital of Thermon, and looted its temples, something that may have given those licensed buccaneers pause for thought.)109 The Romans, at last, were stirred into action. With the Hannibalic war still not settled (despite a recent victory at the Metaurus in 207), Philip could not be left to ravage Illyria unopposed. Complaints from Rhodes and Chios, that the war in Greece—which was in fact the so-called First Macedonian War—was disrupting international commerce, had also made some impression at Rome. In the spring of 205 a Roman task force of thirty-five ships and no less than eleven thousand men landed at Epidamnus.110 This was a considerably larger force than the agreement with Aetolia had envisaged. In fact the whole operation smelled of crude blackmail, since its prime object was not so much to fight as to pressure the Aetolians back into the war. The Aetolians, rightly calculating that this move was a bluff, refused to budge. Thereupon the Romans, refusing an offer of battle by Philip, negotiated a peace of their own. The result was the treaty of Phoenice (summer 205), which finally brought the First Macedonian War to an end.111

There were minor territorial concessions on either side, though the status of Lissos remains uncertain.112 Both sides’ allies were included in the treaty. Philip did well enough out of the negotiations, consolidating his acquisitions in inland Illyria. Rome had ensured the safety of the southern Adriatic, and there may have been those in the Senate who also felt (unlikely as this may seem in retrospect) that the campaign had staved off an active partnership between Philip and Hannibal. In any case, for the next five years or so it was in North Africa, with no Macedonian intervention, there or in southern Italy, that Rome’s legions had to face the Carthaginian; and the affairs of Greece were let slide: the Senate did not even leave holding troops in the Balkans. Philip, too, seems to have felt that Phoenice had finally settled his brush with Rome.

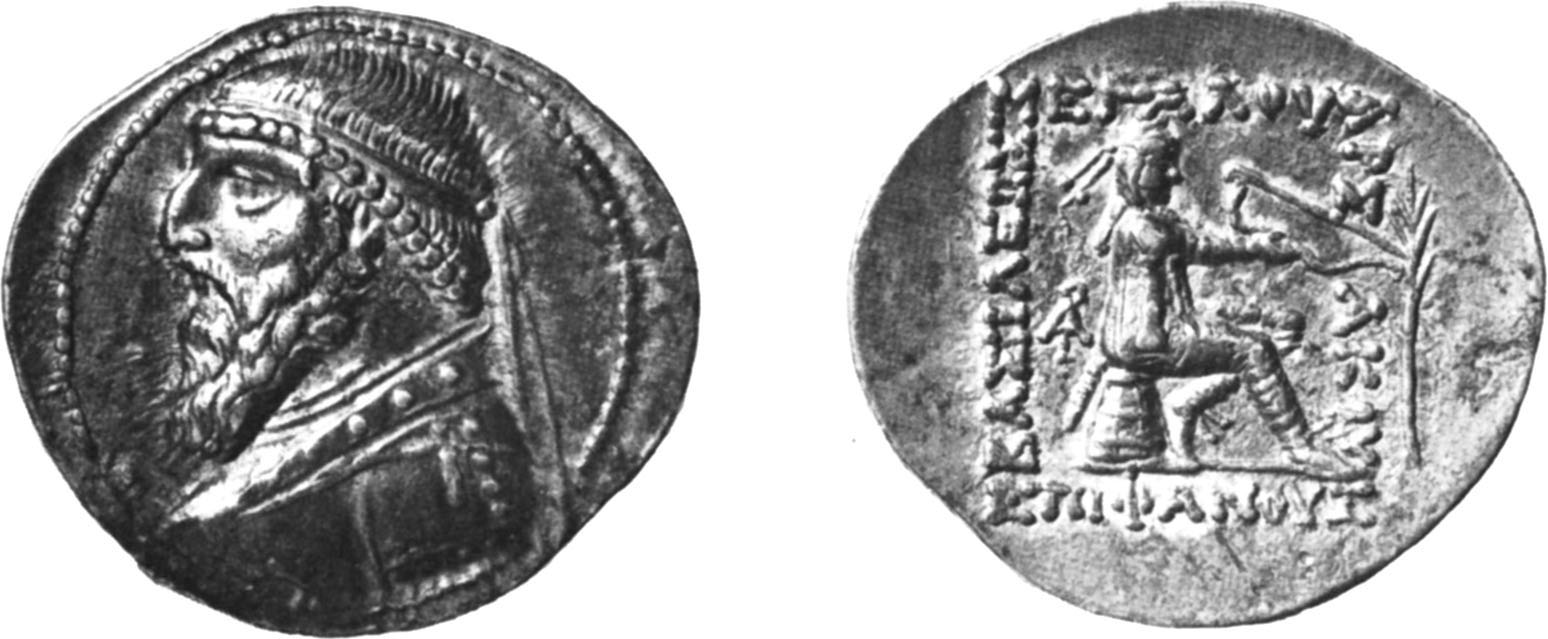

In 205, as always, there were other problems nearer home than the Hannibalic war to occupy all three Successor monarchs, who still thought primarily of the oikoumenē without reference to Italy.113 In Sparta, where all the conditions for social upheaval still existed in acute form, a tyrant named Nabis had recently assumed control of the country (207), after a decade and more of disorganized rule, during which the old dual kingship was ended, and a non-royal military adventurer, Lycurgus—ironically named—bribed his way into a sole monarchy (219: above, p. 286). He died about 211, and his young son Pelops succeeded him, under the guardianship of another ambitious officer, Machanidas. Machanidas perished at Mantinea in 207, apparently in single combat with Philopoemen, and Nabis became king. The tradition is uniformly hostile to him, and should be taken with more than a grain of Attic salt.114 Of his background and activities till his assumption of power nothing is known: his very name, it has been argued, is foreign, a Greek version of the Hebrew nabi, a divinely inspired prophet.115 On the other hand, unlike his immediate predecessor, the mercenary Machanidas, he was no proletarian usurper: certainly a Spartiate, perhaps even a legitimate Eurypontid, descendant of that King Demaratus who was driven from Sparta by Cleomenes I, and ended at the Persian court as adviser to Darius (ca. 491).116 In 205, when he is named in the treaty of Phoenice, Nabis was about forty years old—one coin portrait shows a heavy-jowled, fleshy, bull-necked man in middle age, with a sharply imperious nose117—and apparently guardian to the boy-king Pelops, son of Lycurgus.

How Nabis himself seized power is unknown: probably with the aid of the mercenaries who figured so prominently in his regime, and are described by Polybius as a crowd of murderers, burglars, cutpurses, and highwaymen. Technically, the description of him as a tyrannos is correct.118 That he did away with Pelops is all too likely, and though his brutality may have been exaggerated by his opponents, we need not doubt that he secured his position by the usual methods: banishment, extortion, judicial murder. He is accused, inter alia, of killing off all surviving members of both royal houses, of exiling distinguished citizens and handing out their womenfolk to his mercenaries, of robbing temples in the style of Antiochus Epiphanes, and of collusion in piracy with the Cretans.119 A single, financial, thread can be detected running through most of these charges. Nabis was desperately short of money: for economic no less than sociopolitical reasons the axe fell, above all, on men of property.120 Nabis had no outside financing, from Egypt or anywhere else—the withdrawal of Ptolemy III’s subsidy had been what sealed Cleomenes’ fate (above, p. 260)—and was thus reduced to imposing taxes in order to fund his mercenaries, a familiar problem. He also needed cash to develop a fleet, turn Gytheion into a naval base,121 and complete the building of a fortified city wall round Sparta, now no longer the unwalled yet proudly inviolable capital of the great days before Leuctra.122 The total army he raised, including Lacedaemonian contingents, numbered somewhere between fifteen and eighteen thousand men.123 The cost of all this must have been exorbitant; no wonder he was charged with robbery.124 Yet the Delians, interestingly, greeted him as a benefactor,125 which suggests that they at least had not suffered from his depredations.

All this caused great alarm in the Peloponnese and beyond. Nabis was busy, so report went, not only slaughtering the well-to-do, but also enfranchising foreigners, including mercenaries, and freeing the helots wholesale, moves probably dictated by the depletion of the population through warfare.126 Sparta was becoming a refuge for brigands, runaway slaves, and adventurers of every sort: Nabis encouraged them to use his territory as a base from which to raid surrounding cities, for the most part those of the Achaean League.127 He even supposedly had an iron maiden, fashioned (a nice psychological touch) in the likeness of his wife, Apia, the daughter of an Argive tyrannos, and studded inside with sharp nails, which he employed to torture and kill his opponents: the evidence for this device is so oddly circumstantial that I suspect it may indeed have existed, scholarly incredulity notwithstanding.128

When in 201 Nabis treacherously attacked his current ally Messene (perhaps at the invitation of a populist group within the walls),129 even though he was soon driven off by Philopoemen and a levy from Megalopolis, property owners throughout the Peloponnese took fright. The war that followed was viciously fought (200–198/7),130 with the League forces, to begin with, under Philopoemen’s leadership; but when he was defeated in the autumn election for the 200/199 stratēgia, he left the country to take up a mercenary command in Crete.131 The League had the better of it on the whole so long as Philopoemen remained in command;132 but after his departure Nabis was soon besieging Megalopolis once more.133 In 195 it took Flamininus to disarm—and even then not permanently—this last, and most disconcerting, of Spartan social firebrands (below, p. 417).134 Yet Nabis represented nothing new. In the last resort he was little more than a strong-arm version of Agis or Cleomenes, with even fewer scruples (and indeed unable to afford them). Like his predecessors, he was a nationalist king aiming to restore an elite, this time without even the pretense of maintaining the Lycurgan constitution. Like other Hellenistic monarchs, he ruled alone, and through mercenaries: thus the charge of tyranny brought against him was technically sustainable. He was also hand in glove with the Cretan and Laconian pirates.135 He had the common ambition of late Spartan kings, to revamp his country as a strong, independent, and aggressive power; in the pursuit of this goal he achieved a quite uncommon degree of success, and it was this aspect of his policy that Flamininus, who understood power better than most men, effectively cut short.

At the same time Antiochus III, back from his extended anabasis through the eastern satrapies, was moving on the Hellespont by way of Asia Minor and the Aegean (204–203),136 while in Alexandria the death of Ptolemy IV Philopator, in the summer of 204,137 had been followed by a more than usually bloody conflict over the regency, Ptolemy V Epiphanes being still a child.138 Ptolemy IV’s widow and sister, Arsinoë’ III, was eager for it; but so were his two most powerful ministers, Sosibius and Agathocles, who had Arsinoë murdered. Sosibius’s fate is uncertain; Agathocles held the regency briefly (but long enough to make contact with Rome in 203) before being lynched by the Alexandrian mob, now emerging as an active, if not organized, political force.139 (Polybius describes these events at great length and in vivid, not to say gory, detail, and then assures us that his account is neither too long nor too sensational! Also sprach . . .)140 The five-year-old king was passed from the control of one ambitious adviser to another, and the state of the regime—secession in Upper Egypt, near-anarchy throughout the chōra (above, p. 192)141—positively invited external aggression. Antiochus, for one, could not fail to be eyeing the scene with uncommon interest. Frantic embassies were sent off in all directions: to Antiochus, urging him to respect the peace of 217 (p. 290); to Rome, seeking diplomatic representations to Antiochus; to Philip, offering alliance and marriage; to Greece, to hire mercenaries against the Seleucid threat.142

Bearing in mind Antiochus’s known, and by now highly visible, ambitions on the European front, one might have expected Philip to take this bait. Instead, he and Antiochus made a secret pact to conquer, and share out between them, Ptolemy’s various overseas possessions (203/2)143—a piece of greedy wishful thinking rather than the serious, not to say Machiavellian, statecraft as which it has sometimes been represented. The immediate result was to leave each monarch, for the moment, free to pursue his own aggressive interests: Philip in the Aegean, Antiochus in Coele-Syria and Phoenicia, where he promptly unleashed what is now known as the Fifth Syrian War (202–195). Nor did the pact keep these two royal thieves from very soon falling out with one another: betrayal is more in evidence than mutual aid.144

Antiochus swept down through Coele-Syria (202/1), and after some temporary reverses (most notably at Gaza) inflicted a crushing defeat on the Ptolemaic forces at Panion, near the headwaters of the river Jordan, in a whirlwind campaign that also netted him the key port of Sidon (200/199).145 It was about this time that the same Roman mission as had already issued a stern warning, if not an ultimatum, to Philip (below, p. 307) advised Antiochus to refrain from the invasion of Egypt.146 Since this, on the face of it, was not Antiochus’s immediate intention, there was no reason why he should not return an accommodating answer, and he duly did so. The envoys’ aim was to reconcile Antiochus with Ptolemy, to pour oil on troubled eastern waters. Armed with the Seleucid’s assurances, they proceeded to Alexandria.147 Antiochus was left to complete the subjugation of Coele-Syria at his leisure (198), to raid Ptolemy’s coastal strongholds from Caria to Cilicia, handing out douceurs in the shape of grain consignments and dowries for the daughters of the poor in cities such as Iasos that he “liberated,” and to invade the territory of Pergamon (197/6). Attalus’s outraged delegation to Rome produced no more than a friendly request to Antiochus to avoid territorial infringements.148 But when Antiochus crossed the Hellespont in 196, and began to rebuild the abandoned city of Lysimacheia as a military base and residence for his son Seleucus, the Romans, alarmed at last, treated him as they had earlier treated Philip: he was to relinquish the territory he had won in Asia Minor, refrain from attacking “free” Greek cities, and, above all, keep out of Europe: what Rome had freed, no Hellenistic monarch was to conquer or enslave.149

Antiochus, correctly deducing that this was no ultimatum, and that the Senate had no wish to fight him, took very little notice. Lysimacheia remained his outpost at least till 191/0. He ratified a treaty with Ptolemy that left him in possession of Coele-Syria (195);150 young Ptolemy himself was betrothed to Antiochuss daughter Cleopatra, and in due course married her (194/3).151 The treaty, coming as it did in a period of internal insurrection and attempted military coups, was greeted in Alexandria with relief. It was later asserted there that Cleopatra’s dowry had included Coele-Syria,152 but this can be seen as yet another hopeful court fantasy. When a further Roman mission arrived in Lysimacheia, repeating the Senate’s earlier admonitions (in particular over the matter of Antiochus’s presence in Europe), the king—a smooth diplomat who knew how to utilize public opinion153—challenged Rome’s authority to intervene anywhere in Asia Minor, justified his presence in Thrace by Seleucus I’s defeat of Lysimachus in 281 (above, p. 132), and produced, like a rabbit out of the proverbial hat, his treaty with Ptolemy and his daughter’s forthcoming marriage into the Ptolemaic house as proof of his pacific intentions.154 This constituted a splendid propaganda victory, but it left Antiochus a permanent object of suspicion at Rome.

Meanwhile Philip, after the treaty of Phoenice (205), had decided to build himself a really large and powerful fleet—a notable gap in his armament ever since he had been forced to burn his boats and retreat overland in 214 (above, p. 297). Earlier efforts in this direction had apparently not got very far.155 By 201, however, the fleet was built and in action.156 Philip could now once more hold his own at sea with the navies of Rhodes or Ptolemy or the Attalids. In the anarchic conditions then obtaining throughout the Aegean, he may well also have fancied his chances as a large-scale quasi-official condottiere, a better-organized Demetrius of Pharos. This, indeed, was how he financed his shipbuilding program in the first place (204/3). He commissioned an Aetolian freebooter, Dicaearchus, who embarked on a kind of piratical razzia around the Aegean,157 Illyria and the Adriatic now being off limits. He backed Crete’s pirates against the Rhodian fleet.158 The islands of the Cyclades were terrorized.159 City after city was raided and plundered. Dicaearchus, who finally met his death in Alexandria in 196, had a certain bizarre humor: wherever he anchored his pirate vessels he set up two altars, one to Impiety (Asebeia), the other to Lawlessness (Paranomia).160

By 203 the resultant loot was being poured into the construction of warships, and a year later Philip’s fleet was ready.161 It was now, by no coincidence, that he set up his secret pact with Antiochus. His subsequent activities suggest a continuation of Dicaearchus’s freebooting activities on a larger scale, with a simultaneous eye to strategic advantage. Philip captured Thasos, a useful staging post, and sold the whole population into slavery.162 He systematically raided the Black Sea grain route through the Hellespont and the Propontis,163 which suggests not only economic motivation but also a traditional Macedonian endeavor to extend control in the Thraceward regions toward the Bosporus.164 In 201/0 he captured Ptolemy’s naval base at Samos165—the vessels he captured there brought his fleet up to over two hundred—beat the Rhodian fleet off Lade,166 invaded Ionia, and ravaged the territory of Pergamon.167 Hair-raising atrocities were reported: that febrile, wolfish streak in Philip chronicled by Polybius,168 and clearly visible in the surviving coin portraits,169 was now given free rein.

If Philip was in fact aiming at establishing a general Aegean thalassocracy, over and above raising a little quick capital, his policy was intelligible but his methods can only be described as suicidal. It is doubtful whether any immediate gains he made outweighed the damage that these piratical activities did to his reputation.170 The combined squadrons of Rhodes, Chios, Byzantium, and Pergamon finally put a stop to Philip’s foray in a naval engagement off Chios, where the Macedonian king suffered a crippling and costly defeat, losing almost half his fleet and more men killed than in any previous battle, by land or sea.171 From here he withdrew south to Miletus.172 He regrouped his forces in Caria (where he retained an enclave till 196, the only lasting result of this campaign), but during the winter of 201–200 his fleet was blockaded in Bargylia by Attalus and the Rhodians, and he came within a hair’s breadth of being starved into surrender.173 While he was thus immobilized, envoys from Rhodes and Pergamon hurried off to Rome to denounce his activities.174 It is interesting how quickly Rome, not long since a disregarded barbarian interloper, had become a kind of general arbiter of Aegean affairs. Her defeat of Hannibal at Zama in 202 must have greatly enhanced her prestige and aggressive self-confidence.

By the spring of 200 Philip, having broken through the blockade by a trick,175 was back in Europe, where he promptly got himself involved in a war between Athens and Acarnania: his vision was still fundamentally local. To oblige his Acarnanian allies he sent an expeditionary force to help them ravage Attica.176 He also dispatched a Macedonian squadron, which coolly captured four Athenian triremes from Piraeus. But the Rhodian and Pergamene squadrons that had chased Philip across the Aegean now reappeared from their base on Aigina, and rescued the stolen triremes, to the great delight of the Athenians.177 The septuagenarian Attalus, always on the lookout for opportunities to enlarge his kingdom, was invited to Athens: knowing that a Roman delegation had lately arrived in the city, he accepted. The Athenians, who had just abolished the two tribes, Antigonis and Demetrias, that they had created in a fit of pro-Macedonian enthusiasm a century or so before (above, p. 48), now replaced one of them with an Attalid tribe in honor of the king of Pergamon.178 But it was not until they received assurances that Rome, as well as Rhodes and Pergamon, was committed against Philip that they went beyond giving their guests a good time and actually declared war on Macedonia.179

This was a move they quickly had cause to regret, since no sooner had they made it than their allies found good reasons for needing to be somewhere else. The Rhodian fleet took off to prize loose Philip’s recent acquisitions in the Cyclades, and Attalus returned to Aigina:180 diplomatic cooperation with Rome soon brought him the island of Andros, though, ironically enough, it was at Rhodes’s expense rather than Philip’s.181 Philip’s reaction to the Athenian declaration of war was prompt, vigorous, and characteristic. He set up an advance headquarters on Euboea, and dispatched his general Nicanor to ravage Attica—which Nicanor did to such effect that his troops penetrated as far as the Academy while the Roman mission was still in Athens. Faced with this contemptuous gesture, the Romans had no choice but to deliver an ultimatum to Philip: he was to war on no Greek state, and to settle the wrongs done to Attalus by arbitration.182

Quem Deus vult perdere, prius dementat. Philip, to all appearances not in the least perturbed by the prospect of taking on the military machine that had so recently thrashed Hannibal, and confident that Rome, without even a formal alliance, was in no position to act as protective guardian on behalf of the Greeks, responded to this ultimatum just as he had done to the Athenians’ declaration of war—with a major raid on Attica, led by Philocles, his commander in Euboea.183 Meanwhile he himself led an all-out attack on the cities of the Hellespont, one object clearly being to throttle the Athenian Black Sea grain route.184 So much for not warring on the Greeks. His siege of Abydos proved unexpectedly difficult, and it is a mark of the terror his methods inspired that the inhabitants, facing defeat, preferred suicide to surrender.185 It was here that the senatorial envoy Marcus Aemilius Lepidus caught up with him, carrying a second, and final, ultimatum (summer 200).186 This repeated the first, with two further clauses tacked on. Philip would now have to submit at arbitration to paying damages to Rhodes as well as to Attalus; and, interestingly, he was required to refrain from encroaching on Egypt or Egypt’s possessions.

That Philip actually intended to invade Egypt at this point is out of the question. On the other hand, since a similar warning was issued to Antiochus (above, p. 304), it is more than possible that the Senate had got wind of the secret pact between the two rulers. There was a sharp exchange with Lepidus over the responsibility for aggression: Philip stood his ground, refused to be intimidated. After his undignified retreat before Roman squadrons in 217/6 and 214, this may have come as a surprise. If there had to be war, he said, then the Macedonians would give a good account of themselves. At this point Lepidus broke off the discussion and left. Philip, still unperturbed, pressed home his assault on Abydos, announcing to the inhabitants, with mordant irony, that if they wanted to commit suicide, they had three days in which to do so. They took him at his word, to the last man.187 Never can gallows humor have fallen flatter. Philip then set out for Macedonia. Meanwhile, after one rejection, the proposal for war was finally, on resubmission, ratified by the Roman comitia centuriata.188 Philip was not yet home when news reached him that a Roman army had already landed at Apollonia (autumn 200), and a Roman fleet was wintering in Corcyra.189 The wanton destruction of Abydos, the insolent rejection of a conciliatory Roman envoy, had finally brought Roman public opinion round—too soon after the long Punic struggle—to the prospect of yet another conflict.190 A new, and ultimately fatal, phase in Macedonian affairs had begun.

The great question, of course, is why Rome, at this juncture, should have gone to war with Macedonia at all. From the Roman viewpoint there had been no change of situation in Illyria since 205: Badian’s picture of “Roman fear and Roman hatred” is, at best, an exaggeration.191 Philip’s pact with Antiochus, even if known, was hardly of real interest to Rome, and certainly not that threat to the balance of power in the Hellenistic world as which it has sometimes been represented.192 Philip and Antiochus were too busy cheating each other to form a stable Seleucid-Antigonid coalition,193 and in any case the history of the Successors had shown just how fragile such alliances tended to be. No concern for the Senate there. A war in defense of allies, then? But the allies, in any formal or technical sense, did not exist: Polybius never mentions them, and he was the last man in the world to suppress evidence so favorable to a portrayal of Rome as the honest broker fulfilling her legal commitments.194 Could Philip have been regarded, or indeed (bearing his ancestry in mind) have vaunted himself, as the new Pyrrhus?195 But Pyrrhus had looked westward, had indeed invaded Italy (above, pp. 228 ff.), whereas Philip’s interests had all been in Illyria and the Aegean, areas for the most part (and not least since the peace of Phoenice) remote from Rome’s immediate interests. There was, as we have seen, no conceivable risk of a Macedonian seaborne invasion of Italy, least of all since Hannibal’s defeat. Nor is it plausible that Rome should now seek revenge on Philip for his dead-letter treaty with Carthage, much less go to war with Macedonia on behalf of Athens. (In the event, the Athenians found themselves fighting on their own, since neither Rome, Attalus, nor the Rhodians gave them adequate support.)196 There is no evidence for a renewed threat to the Adriatic: Philip was now concentrating all his efforts on the Hellespont.

Indeed, a state of war was reached only with extreme reluctance, certainly on the Roman side: many in Rome did not want it at any price. It was too soon after Zama for another major conflict. On the other hand, no one had expected such defiance from Philip, who had been cast, in senatorial eyes, for the familiar role of obligated client-prince;197 and Philip, for his part, had good reasons for believing that Rome would avoid war at all costs. Both sides, in the event, were wrong: neither would back down. “Miscalculations are no small factor in the creation of war.”198 It is, of course, always possible that the Senate, after briefing by Lepidus, saw Philip as a dangerous and ambitious lunatic who would, when the time came, stop at nothing, a view to which his behavior at Abydos must have lent some plausibility.199 Certainly no one had forgotten the treaty he struck with Hannibal; even if that in itself did not offer an adequate casus belli, it was an eloquent indication of untrustworthiness.

Face-saving, then, combined with a preemptive strike against a potential, and growing, menace?200 The miscalculation once granted, this seems at least possible; nor was the time badly chosen. After his ruthless freebooting activities in and around the Aegean, Philip was, not surprisingly, strapped for allies. Rome had ensured the nonintervention of Antiochus, who in any case was only too ready to profit by Philip’s misfortunes. The Achaean League, itself now at war with Nabis of Sparta (above, p. 302), was seriously divided. It began the war as Philip’s titular ally,201 though in effect maintaining neutrality, and not encouraged by rumors that Philip was trying to have Philopoemen assassinated.202 Philip’s main supporter in Achaea was exiled; his successor as stratēgos, Aristaenus, was eager for a rapprochement with Rome.203 Dissension ran deep. Eventually a divided League voted for Aristaenus’s proposal.204 The deciding factor in choosing Rome over Philip was almost certainly the better chance Rome offered of dealing with Nabis and strengthening the League’s position in the Peloponnese: the outlook, as always, remained parochial.205 The League’s defection left Philip highly vulnerable.

In 199 the Aetolians too, after cautious hesitation, finally committed themselves to Rome, but only because it looked by then as though Philip would lose.206 A similar belief encouraged Athens, long restrained by fear, and the anxiety of dealing on her own with Macedonian incursions, to enact (200/199) a hysterical reversal of all the lickspittle honors that the Council and the Assembly had previously voted Philip: the statues were to be pulled down, the feast days and priesthoods were to be abolished; the priests, whenever they prayed for Athens and her allies, were also bidden to “curse and execrate Philip, his children and kingdom, his sea and land forces, and the entire race and name of the Macedonians”; any anti-Philip decree was to be adopted nemine contradicente, anyone making a proposal that could be construed as favoring him could be killed with impunity as an outlaw; finally, all the anti-tyrannical legislation enacted against the Peisistratids should be reactivated to deal with Philip.207 “It was,” Livy remarks, “with writings and words, their only strength, that the Athenians waged war against Philip.”

It is sometimes argued that Philip also alienated his own upper classes by promising better conditions for the underprivileged;208 but for this there is no serious evidence, certainly not his habit (familiar in many other earlier Macedonian monarchs, not least Philip II) of wearing ordinary clothes and affecting to be a man of the people.209 Philip’s favor, like that of his predecessors, always went to the aristocrats on whom he primarily depended. Setbacks certainly did not improve his temper. In the fall of 200, having failed to capture both Eleusis and Athens, he subjected Attica to the kind of wholesale pillaging and devastation that had not been seen since the Persian Wars.210 For the next two years his fearsome energy, coupled with an indifferent opposition, kept him well in control of the situation. He was here, there, and everywhere. He bottled up a Roman army in the mountains of Illyria, drove back the Aetolians to the south, crushed a Dardanian invasion from the north.211 But in 198, with the arrival in Greece of the young consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus, the tide at once began to turn.

What Edouard Will describes as “militant philhellenism”212—whether genuine on Flamininus’s part, or, more probably, a mere new instrument of anti-Macedonian political pressure213—was now to be the order of the day. A meeting between Flamininus and Philip at the Aoös River in Illyria proved abortive: Philip stormed out in a rage on hearing the Roman terms—peace only if he evacuated his Greek strong points (Thessaly, Euboea, Corinth), cities to be ungarrisoned and autonomous.214 According to Diodorus, Flamininus claimed, already, to have a senatorial commission to liberate Greece, but this seems unlikely.215 The emphasis was still all on getting Philip out of Greece rather than deciding the status of the Greek states when he was gone.216 Flamininus, after the breakdown of the talks, lost no time in driving Philip’s forces back into Thessaly, where Philip carried out a desperate scorched-earth policy in sharp contrast with the Roman’s carefully calculated restraint: no looting, no atrocities.217

By the later summer of 198 Rome’s legions were on the Gulf of Corinth. Flamininus worked hard on the dissident members of the Achaean League: most came over, though one or two, Argos in particular, held out for Philip. In November Philip, thus robbed of his allies, tried once more for peace.218 In a conference at Nicaea near Thermopylae he once more was presented with terms that virtually restricted him to Macedonia, and negotiations stalled. But this was election year for Flamininus: he told Philip to send an embassy to Rome—where (as he had anticipated) negotiations broke down over Philip’s retention of Demetrias, Chalcis, and Corinth, the Fetters of Greece219—while he himself spun out discussions till he was confirmed in his proconsulship, then took the field again. Philip, desperate, now sought alliance where he could find it, which meant with Nabis of Sparta, and, as a bait, turned over Argos to him; he also betrothed his daughters to Nabis’s sons. The Spartan subjected his new possession to a reign of terror (a nice reward to the Argives for their loyalty), and then added insult to injury by promptly turning round and making a deal with Flamininus. This stipulated an armistice between Sparta and the Achaean League till the war with Philip was over, and bound Nabis to supply Flamininus with auxiliary troops for the prosecution of the war itself.220 Rome throughout this period remained extremely cavalier about such ad hoc wartime associations, and indeed always avoided any more binding commitments in Greece: the Achaean League, for instance, was repeatedly put off in its quest for a written alliance.221 Nabis could expect nothing better.

Philip’s army was by now reduced to some twenty-five thousand men: like Antigonus One-Eye, like Lysimachus, like too many of his predecessors, he decided to stake everything on a single battle. At Cynoscephalae (“The Dogs’ Heads”), in Thessaly, he came within an ace of destroying Flamininus’s legions with a massed charge of the Macedonian phalanx (June 197)—a terrifying spectacle, even for battle-hardened Romans—and indeed one phalanx was completely successful. But the other overreached itself, lost formation, and was cut to pieces; the rest of the army was then broken up by a flank attack, something to which the phalanx proved highly vulnerable. In close formation, and on level ground, the charge of the phalanx was regarded as all but irresistible; but its flanks and rear remained open to attack, even when screened by cavalry or light-armed troops. The Romans used variations on this type of attack not only at Cynoscephalae, but also later against Antiochus III at Magnesia (p. 421) and the Achaean League troops outside Corinth in 146 (p. 452). Another technique available to a seasoned legionary commander was to loosen the compact formation of the phalanx, with its bristling hedge of leveled pikes (sarissas), by tempting it onto uneven or otherwise unfavorable terrain (a good example of the tactic is its use by Aemilius Paullus at Pydna in 168; cf. p. 430). It was the adaptability of the disciplined legionary to changing tactical requirements, as Polybius saw,222 that gave him the edge over his counterpart—equally disciplined, but far less flexible—in the phalanx.223

Cynoscephalae was the first victory over a Greek army by Romans in a major pitched battle; but it left Rome absolutely in control of the situation in Greece. After his defeat Philip agreed perforce—having burned the royal archives at Larissa to avoid embarrassing diplomatic revelations—to rather stiffer terms than those he had earlier rejected.224 He would evacuate Greece. He would pay a thousand-talent war indemnity. The Greek cities of Europe and Asia (this last clause for Antiochus’s attention) would be free; at the same time—again because of Antiochus225—Rome judged it prudent to keep garrisons in Demetrias, Chalcis, and Acrocorinth, the Fetters of Greece.226 However, at the Isthmian Games of 196, after considerable Greek pressure on the Senate,227 Flamininus, as part of his commission, solemnly proclaimed the freedom of the Greeks, with a roll call of all those—Corinthians, Phocians, Locrians, Euboeans, and others—who were henceforth to be autonomous, ungarrisoned, exempt from tribute, in possession of their ancient laws.228 His knowledge of the language may have been less than perfect, his cultural aspirations dubious, his philhellenism primarily a persuasive instrument with which to implement Roman Machtpolitik;229 but his timing, on this occasion, was impeccable. The Greeks assembled for the games greeted his proclamation with delirious enthusiasm. Titles and honors were showered upon him.230 We have heard the same slogan often enough, and so had they, but never before from a Roman.

And what, in the last resort, did it mean? Perhaps Livy came nearest the mark when he defined this libertas as a munus, a privilege bestowed by Rome as part of the benefits accruing to a foreign client.231 Flamininus’s evacuation of Greece in 194 is so described (below, p. 418): his announcement of it, in Livy’s version, is heavy with paternalism, with a lively awareness of mutual obligations. Formal Roman clientship (clientela) is too narrow a term; once again, as in his public acknowledgment of eleutheria, the Roman is drawing on a well-established Hellenistic custom, that of euergesia, benefaction. It should have escaped no one’s notice that, despite all the heady talk of freedom, Eretria in Euboea had been made over—the reward for a faithful client-prince—to Eumenes of Pergamon.232 (Old Attalus had had a stroke the previous year while making a speech in Thebes, and died some months later: his son succeeded him without incident.)233 From now on—as every Greek diplomat knew, and however unwilling senators might be still to tie their country to Eastern commitments—it was to be Rome that exercised the patronage.