Hellenization, the diffusion of Greek language and culture that has been defined, ever since Droysen’s Geschichte der Diadochen (1836), as the essence of Hellenistic civilization, is a phenomenon calling for careful scrutiny.1 Its civilizing, even its missionary aspects have been greatly exaggerated, not least by those anxious to find some moral justification for imperialism; so has its universality. On the other hand, despite the labors of scholars such as Rostovtzeff, this trend has been matched by a persistent tendency to underplay the lure of conquest, commercial profits, and generous land grants (below, p. 371), which provided the main driving force behind this Greek diaspora—not to mention the stubborn refusal of allegedly inferior races to embrace the benefits of Greek enlightenment thus rudely thrust upon them. It was, significantly, no king or conqueror, but wandering Cynic philosophers such as Diogenes—dropouts from the affluent bourgeois society of the Successor kingdoms—who described themselves as “citizens of the world” (kosmopolitai),2 and talked about an equality based on the common nature (physis) of the human animal. Whatever their mission may have been, it was not to promote the ethics, morality, and political organization of a system they had rejected.3 Yet such odd men out remained an insignificant minority. Despite the widespread adoption (by the kosmopolitai among others) of Attic koinē as a Hellenistic lingua franca, it is notable—and symptomatic—how resistant it remained to foreign loan words.4

An analysis of the extant evidence is revealing. The Greeks had long assumed in themselves, partly on environmental grounds, a cultural superiority over all alien societies5—a superiority that even extended, in the visual arts, to idealizing themselves, while portraying outsiders with a realism often not far this side of caricature6—yet this never manifested itself as a compelling urge to convert or enlighten the barbaroi, whom no less an intellectual than Aristotle regarded as slaves by nature, to be treated like animals or plants.7 In classical drama—for example, Aristophanes’ Acharnians (425) or Thesmophoriazusae (411), and Euripides’ Orestes (408)—the jabbering foreigner had always been good for a laugh.8 No one ever thought of educating him. Isocrates in the fourth century might argue—in deference to the sophistic notion that aretē (that quintessentially Greek quality, virtue and natural capability combined) could be taught as well as inherited—that Greekness was a matter of attitude, not blood, to be got from a proper training in Greek culture (paideia);9 but he still shouted louder than anyone for a crusade against the barbarian. Curiosity about the rest of the world undoubtedly existed, but was not, perhaps mercifully, accompanied by any inclination to improve it.

Thus the dissemination of Hellenism, when it came, was incidental rather than conscious or deliberate, an important point. Further, those Macedonian soldiers and Greek businessmen who exploited the indigenous populations of the great Successor kingdoms could not, by any stretch of the imagination, be regarded as a cultural elite. The stupid, bombastic, drunken, cowardly miles gloriosus who appears in literature from Menander’s day onwards (above, p. 74), with his toadying servant and chestfuls of Persian plunder, had all too real a basis in fact. Such men were massively indifferent to the language and civilization of any country they happened to be occupying, an attitude that their victims, for the most part, reciprocated. Even in the heavily Hellenized areas of Syria, Phoenicia, and Cyprus bilingual inscriptions are common; Aramaic remained the second language of Antioch, and was spoken as the vernacular throughout Syria long after the Roman conquest.10 It was the polyglot poet and anthologist Meleager of Gadara (fl. ca. 100 B.C.) who wrote, sardonically, “What’s so surprising about my being a Syrian? You and I, friend, inhabit one country—the world,” a fine Stoic sentiment, and then ended his own epitaph with the Syrian, Phoenician, and Greek words for “farewell,” not perhaps quite what the Stoics had in mind.11 Alexander’s racial fusion de haut en bas died with its begetter, but the cosmopolitanism of Diogenes had come to stay.

Any Egyptian who wanted to get anywhere under the Ptolemies had to speak, and preferably also write, koinē Greek. We have a letter of complaint (ca. 256/5) to an official from his (probably Egyptian) native servant about the contemptuous ill treatment he has received “because I am a barbarian,” and petitioning for regular pay in future “so that I don’t starve because I can’t speak Greek.”12 Similarly, an Egyptian priest is resentful at a Greek settler who “despises me because I am an Egyptian.”13 Though later, as we shall see, a certain degree of low-level acculturation took place, in the fourth and third centuries imperial racism was rampant among the Greeks and Macedonians of Alexandria, and never entirely died out. The King’s Friends excluded all non-Greeks from their circle. Alexandrian marriage customs remained, as several scholars point out, ultra-Greek for the Greeks; it is also remarkable how many residents clung to the citizenship of their own polis rather than assuming that of Alexandria. The list includes most of the major third-century poets and scholars except for Apollonius, who was in any case Alexandrian by birth (pace Professor Lefkowitz; cf. p. 783). No Macedonian of note before Cleopatra VII, and very few Greeks, would ever learn Egyptian, so that the administration (still, ironically, in essence pharaonic) functioned, at middle level, through a corps of more or less bilingual native interpreters and scribes.14 Competition for such posts, now as in the earlier pharaonic period, was intense. On the other hand the Hellenized Egyptian was not required to read, much less to enjoy, Greek literature, any more than his masters knew, or cared about, the age-old literary heritage of Egypt. Such assimilation as took place tended, in the first instance, to be among the illiterate or culturally indifferent lower classes; and here it was the alien Greeks, who, by intermarriage and religious syncretism, slowly became Egyptianized,15 a pattern that repeats itself elsewhere in the oikoumenē from the second century onwards.

Borrowings and adaptations, then, we would expect to find in those areas that, first, required no linguistic skill, and, second, were commonly accessible without conscious intellectual effort: that is, the visual arts, architecture, and music. Apart from music, for which there is only sketchy literary evidence (suggesting possible Oriental influence on Greek modes and instruments rather than vice versa),16 this is precisely the case. Yet even in the area of art and architecture, what is often pointed to as evidence for cultural dissemination is, in the sense proposed, nothing of the sort. I am thinking particularly of the export of Greek building styles, pottery, statuary, gymnasia, temples, theaters, and the rest of the civic impedimenta essential for any self-respecting polis, into areas as far afield as, say, Bactria. Aï Khanum, on the Oxus, is a good case in point (cf. below, p. 332). Probably founded by Alexander as Alexandria Oxiana,17 Aï Khanum, like all such cities, was settled exclusively by Greek and Macedonian colonists. In Bactria, colonists apart, no less than 13,500 troops were left behind by Alexander, more than enough to form what has been accurately described as “the nucleus of a central Asian Greece.”18 Thus, far from any kind of diffusion, what we find in such cases is an alien enclave, an artificial island of Greek social and cultural amenities almost totally isolated from the indigenous population that it dominated. There were areas of contact, even of interpenetration, but these were few, and brought about by special circumstances.

That much-touted respect for exotic alien wisdom occasionally found in Greek literature—for example, Herodotus’s astonishment, later shared by Plato and Aristotle, at the hoary, unchanging, Egyptian priestly tradition19—depended in the main on unfamiliarity (because of the language barrier) with the literature in which such wisdom was enshrined. Nor do we find, per contra, any substantial evidence in the Seleucid East or India for local interest in Greek literature or Greek ideas, but rather a great deal to suggest implacable hostility, with a religious and ideological no less than an ethnic basis.20

Local acclimatization tended, inevitably, to be restricted to two well-defined categories. On the one hand we find those still-independent rulers who went Greek for their sociopolitical advancement. On the other, there were the intelligent and ambitious collaborators who set out to make a career in the administrative system of the occupying power: in the Seleucid empire, it has been calculated, not more than 2.5 percent of the official class, and that only after two generations.21 These were the men who became interpreters, who acquired jobs as clerks, tax collectors, accountants, or other categories at subexecutive level in the bureaucracy, with an outside chance of clawing their way up the ladder of advancement to positions of real power as senior administrators or military officers (including police). By so doing they committed themselves to the foreign regime they served in a social no less than a professional sense. Like Indians under the British Raj angling for the entrée to European club membership, they developed the taste for exercising naked,22 for worshipping strange gods, for patronizing the theater; they courted municipal kudos by the lavish generosity of their benefactions. The prime motive in such cases was, clearly, social and professional ambition, even if a little genuine acculturation took place at the same time. Against this must be set that deep resentment and hostility felt by most of their fellow countrymen toward an occupying power (not to mention the angry contempt, mixed with jealousy, that they themselves would attract), and, on the Graeco-Macedonian side, a powerful distaste for those who in any sense went native.23 It took a liberal intellectual like Eratosthenes, even in the Hellenistic age, consciously to challenge such an entrenched attitude.24

When all these factors are taken into account, a radically modified picture of Hellenization emerges, restricted, for the most part, to some curious instances of architectural and glyptic hybridization; some social assimilations among non-Greek rulers and in the administrative sector of the major kingdoms (particularly the Ptolemaic); a few religious syncretizations that transmuted their borrowings out of all recognition (e.g., Isis and Sarapis); and the establishment of the Attic koinē as a useful international language, primarily for administrative and commercial purposes, but also, later, for religious propaganda. This does not mean that the Greek and Macedonian colonists failed to have a profound impact on the societies they controlled, particularly through the widespread colonization of the Seleucid empire (cf. p. 372); but this impact was, first and foremost, economic and demographic rather than cultural. As we shall see, it is hard to track the conscious diffusion of Greek intellectual ideas in the Hellenistic East with any real confidence, and of genuine literary interpenetration between Greek and other cultures there is virtually no trace. For one thing, literary translations—as opposed to those of medical, mathematical, astronomical, or similar practical treatises (p. 325)25—seem to have been nonexistent, a sure sign of esthetic indifference.

Thus whatever the Greeks and, a fortiori, the Macedonians were up to (over and above financial exploitation) in the kingdoms ruled by Alexander’s heirs, spreading cultural light formed a very small part of it. Itinerant sophists might peddle the latest philosophical clichés of Academy or Stoa at street corners, and the local-boy-made-good, with his Greek-style education,26 would have a stock of well-worn quotations from Homer, Euripides, and Menander at his disposal. It does not add up to very much. To what extent the locals would patronize a Greek theater (e.g., that of Aï Khanum in Bactria), and what they absorbed, or even understood, if they did, remain highly problematic questions.

The failure of Hellenism to catch hold among the indigenous inhabitants of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid kingdoms thus has nothing to do with its intrinsic intellectual or cultural merits as a system of ideas, a creative matrix, a way of life. It failed for several good and compelling reasons wholly unrelated to the criteria by which we would assess it: the bitter resentment of defeat, which found expression in passionate ethnocentrism; a theocratic temper that subordinated arts and sciences alike to the requirements of religion,27 and was chary of translating religious texts; a language barrier that no one cared to break except for the immediate requirements of commerce and administration. This general rejection throws into prominent relief the two striking exceptions for which we have evidence, and in both cases, as is at once apparent, special circumstances apply.

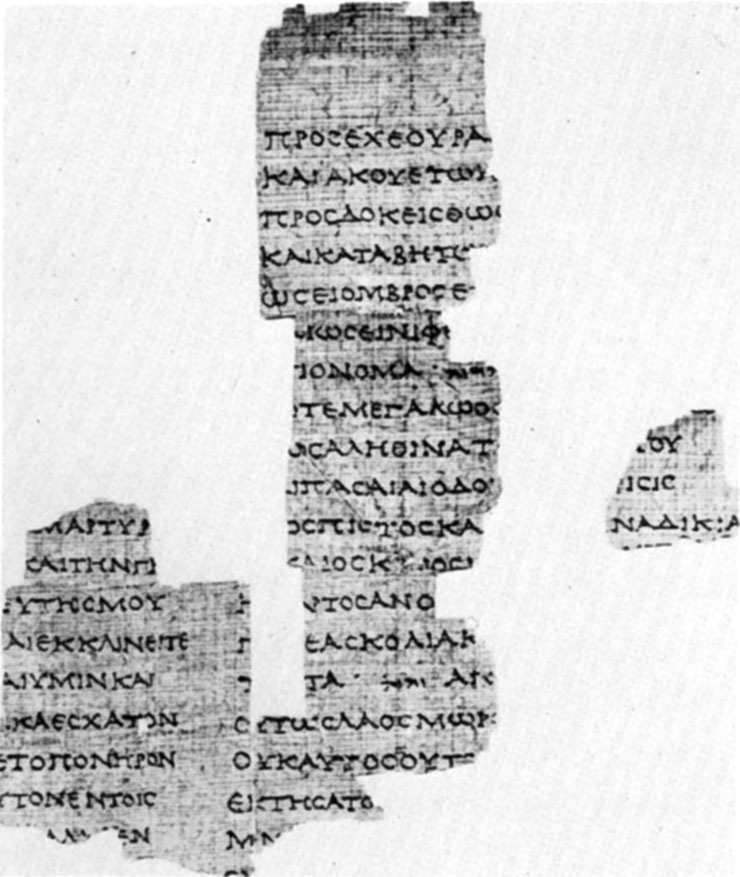

The first concerns the large and influential community of Jews in Alexandria, perhaps originating as prisoners of war settled there by Ptolemy I.28 This community, though ethnically debarred by its own religious laws from intermarriage, contained a high proportion of intellectuals, and, equally important, became bilingual in Greek. To a surprising extent, the external aspects of synagogue ritual were adapted to Greek custom.29 In the third century the Torah was translated into Greek, an act with far-reaching consequences. Even more important was the production, perhaps begun under Ptolemy II, but not completed till the second century, of the Septuagint, the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible.30 It is noteworthy that the prime motive for translation in this case was the increasing inability of the Greek-speaking Alexandrian Jews to understand either Hebrew or Aramaic. As a result, a considerable body of Helleno-Judaic literature passed into circulation.

Yet, once again, despite favorable conditions for direct mutual influence—they were all living in the same city, must often have passed one another in the street—the evidence reveals an almost total lack of contact, certainly in the third century and arguably for much longer, between this Jewish Alexandrian literary movement and the contemporary tradition of Callimachus, Theocritus, and their successors. The cognoscenti of the Museum reveal no interest in, or knowledge of, the prophetic mode of discourse so characteristic of Jewish thought,31 while the dominant influence on Jewish Alexandrian literature is not Homer, much less Callimachus, but the Septuagint. The form and substance of those works that survive remain Jewish, prophetic, religious-inspired throughout. The nearest we come to classical influence is an extraordinary fragment of tragedy, in flat iambic trimeters, entitled Exodus, and covering most of the life of Moses, which has little literary merit, but does at least reveal familiarity with the language and meter of Euripides. There are also some unremarkable fragments of epic: Philo Senior on Jerusalem, Theodotus on the Jews, filtered through to Eusebius by way of Alexander Polyhistor. This could hardly be described as an impressive cross-cultural record.32

The one shining exception to all these predictable, if depressing, conclusions is, of course, provided by the greatest, and most historically significant, cultural confrontation of them all: that between Greece and Rome. Though the lack of a homegrown intellectual tradition has probably been exaggerated, the familiar picture of “captive Greece captivating her savage conqueror, and bringing the arts to rustic Latium” remains true enough in essence.33 The Roman attitude to the Greeks was, predictably, ambivalent. On the one hand they swallowed Greek culture whole (a feast that gave the more old-fashioned among them severe indigestion), imitated Greek literature, rehashed Greek philosophy in ponderous, awkwardly abstract Latin, sedulously pastiched Greek art. On the other, perhaps not least because they “had eaten of the apple of knowledge and knew themselves to be culturally naked,”34 a situation always liable to arouse resentment, they despised and mistrusted the Greeks themselves as slippery, unreliable, unwarlike, covetous mountebanks, confidence tricksters with no moral principles and a quicksilver gift of the gab.35 Paradoxically, it was (as Horace notes) on the one occasion when the Greeks came as a defeated nation rather than as conquerors that their culture had most influence. The ambivalence is shared by Polybius, who identified Rome’s moral decline with the hedonistic ways her jeunesse dorée picked up from the Greeks after Pydna, but was well aware of the need to emulate them in cultural matters.36 Though they could not fight like Spaniards or Carthaginians, it was felt, they understood the power of words.37 Condescension of this sort could cut both ways: Philip V somewhat patronizingly announced himself impressed by the military organization of these “western barbarians,” a term that Cato the Elder later found Greeks still applying, along with other ethnic slurs, to the Romans, and to which he took great exception.38

No accident, either, that it was the Romans—the most enthusiastic promoters of Hellenizing standards, perhaps because they were so morbidly conscious of being cultural parvenus themselves—who were seriously worried about the real or fancied decline of those standards. After all, as Cicero reassured them, they themselves had either shown more inventiveness than the Greeks, or at the very least had improved anything the Greeks had taught them to which they cared to turn their minds.39 Livy puts into the mouth of the consul Gnaeus Manlius remarks that suggest he has very little time for the latter-day Macedonians of Alexandria and Seleucia and Babylon: they had, he observed acidly, “degenerated into Syrians and Parthians and Egyptians.”40 Juvenal in his notorious anti-Greek tirade makes precisely the same point. What proportion of the dregs that are washed across from Orontes to Tiber, he asks rhetorically, is really Greek anyway? In they swarm, with their unintelligible native lingo and disgusting habits and weird musical instruments and gaudy prostitutes, to corrupt decent Romans.41 Long before the end of the first century A.D. Rome had taken over the Greek xenophobic attitude to barbaroi, and was applying it, with gusto, to the Greeks themselves.

This ingrained sense of superiority, whether masquerading as panhellenism to sanction the rape of the East, or, later, helping to keep Ptolemies and, to a lesser degree, Seleucids in cultural isolation, century after century, from the peoples they ruled and exploited, is an extraordinarily constant factor in the history of the Hellenistic era. The Macedonians in particular began with a total indifference to, and contempt for, the cultures on which they imposed their government, even though in the interests of profit they were more than willing to take over, not only existing modes of production, serf labor, and land tenure (particularly throughout Asia), but also the (sometimes familiar) forms of municipal government they found.42 Alexandria was “by” Egypt, yet not of it:43 Alexander’s attempts at racial fusion were abandoned immediately after his death, and Egyptians in Alexandria suffered from constitutional discrimination. Seleucus, alone of his marshals, remained faithful to the “Persian” (actually Bactrian) wife, Apame, wished on him at the time of the Susa mass marriages,44 so that the subsequent dynasty was by blood mixobarbaros; but this had less influence on Seleucid policy than has sometimes been supposed.

In all instances what the Successors set up were enclaves of Graeco-Macedonian culture in an alien world, governmental ghettos for a ruling elite.45 When we come to assess the ubiquitous Greek temples, Greek theaters, Greek gymnasia, Greek mosaics, and Greek-language inscriptions scattered throughout the oikoumenē, we should never forget that it was for the Hellenized Macedonian ruling minority and its Greek supporters, professional or commercial, that such home-from-home luxuries—not to mention the polis that housed them46—were, in the first instance, provided. In Egypt, and probably elsewhere, the gymnasium resembled an exclusive club: entry was highly selective, by a scrutiny (eiskrisis) designed to keep out undesirables (i.e., non-Greeks) and to foster Hellenism. There was a waiting list, and children from suitable families were put down on it from a tender age.47 Only by the very end of the Ptolemaic period were wealthy local citizens sometimes admitted.48 In the Seleucid East the racial barrier was less strictly applied, though a non-Greek gymnasiarch was still a rarity,49 and athletic victories—apart from those won by hired jockeys in the horse and chariot races on behalf of rich local nabobs—were restricted almost without exception to Greek competitors. In Greece itself, in the third century, we find the occasional Hellenizing non-Greek winning chariot or athletic races at Nemea or on Delos (e.g., an Aramaic Sidonian who called himself Diotimus), and Romans doing likewise at the Isthmus; but these isolated instances have less cultural significance than has sometimes been claimed for them. It is hard to argue with the assertion that “on the whole, the gymnasia did little to further an understanding between the Greek settlers and the native population, and did a lot to keep them apart.”50

Against the degeneration alleged by Livy and Juvenal we can set the remarkably pure Greek still written in Doura-Europos even after a century of Parthian rule, and Tacitus’s admission that the Greeks of Seleucia-on-Tigris had not, even in his day, “declined into barbarism.”51 It is also true that a fair number of the local inhabitants, especially those who were socially or politically ambitious, took full advantage of such openings as the Greek gymnasium culture offered. A native eager to get on in this new imperial world had to cooperate with the regime, just as a local princeling would often be eager to show himself au fait with Greek manners. In some of his most mordant poems Cavafy exactly catches the nervous, snobbish cynicism that inevitably characterized such arrivistes:52

Since so many others more barbarous far than usMake this sort of inscription, we’ll inscribe it too.Anyway, don’t forget that sometimesAnd verse-cobblers, and other such fribbleheads,So that un-Hellenized we’re not, I think.

Cavafy is satirizing, inter alia, the regular use by Asiatic dynasts of the title “Philhellene,” only appropriate for someone who in fact stood outside the Greek world, looking in.

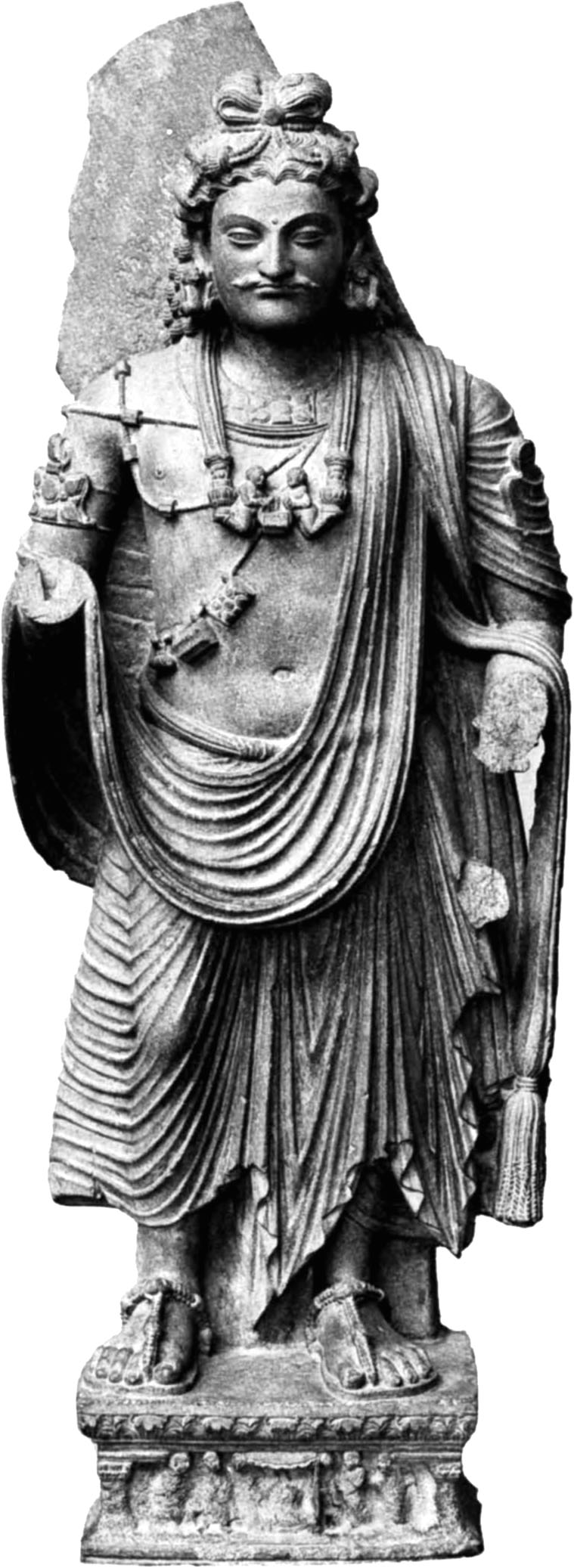

Again, the parallel of British India springs to mind, where the acceptance of English as a lingua franca, and the appetite of numerous educated Indians for such plums of power as they could grab within the system as it stood (along with the social mores of club or cantonment), in no way mitigated the deep-abiding resentment of British rule, much less made any inroads against India’s own long-standing cultural and religious traditions. Another interesting parallel is the way in which the scions of Anatolian royal families, for example Ariarathes V of Cappadocia or Nicomedes IV of Bithynia, were sent west for their education, normally to sit at the feet of the reigning philosophers in Athens, “like the vassal princes of the Indian empire who were sent to Harrow and Sandhurst;”53 it is symptomatic that what these two took home as a result of their experiences was a superficial taste for Greek theatricals.54 Further, just as a surprising number of Englishmen, despite their own rigid caste system and xenophobic assumptions, were fatally seduced by the lure of Eastern mysticism, so the Indo-Greeks, in a very similar situation, capitulated to some highly un-Greek local influences before they were done. Indian legends and Indian scripts invaded their coinage. Even if the notion of portraying the Buddha in human form was a Greek innovation,55 their sculpture and reliefs and architecture absorbed far more than they imposed.

Menander, perhaps the greatest king of the Indo-Greeks (r. ca. 160–130), and the only one remembered in later Indian tradition, may have set Pallas Athena on the reverse of his coins,56 but he was also, in some sense, a convert to Buddhism (traditionally because of discussions with the Buddhist priest Nagasena)57 who employed the Dharma-Chakra (Wheel of Law) symbol, and was associated in tradition with the building of stupas and the original iconography of the Buddha image.58 Greek sculpture adapted itself to the lotus posture, and—after a gap of four centuries— came up with a new and more enduring version of the mysterious “archaic smile.” The ghost of Apollo still lurked behind the Buddha’s features, but it was a losing battle.59 Absorption was slow but inevitable; by the time that the Indo-Greek and Graeco-Bactrian kingdoms finally vanished amid the incursions of Sacas, Parthians, and Kushanas (130–100), their inhabitants had been thoroughly Orientalized. By then—but not till then—Narain’s verdict had come true: “Their history is part of the history of India and not of the Hellenistic states; they came, they saw, but India conquered.”60

If it had not been for the Romans, whose strong obsession with Greek culture formed part of the overall imperial legacy that Rome disseminated throughout her far-flung provinces, the impact of Hellenism might well have been less fundamental, less widespread, and less enduring. As it was, Rome achieved a larger, and certainly a more cohesive, empire than Alexander had won—yet one that remained, in essence, a Mediterranean phenomenon. When we talk about the oikoumenē, this should always be borne in mind. Even before Rome’s ascendancy, the oikoumenē was for the most part limited and defined (certainly in the minds of those who exploited it) by Alexander’s conquests. In other words, it was an eastern Mediterranean complex, with large but ill-defined Oriental extensions. Northern Europe and Asia, the whole vast African continent south of Egypt and Cyrene, whatever lay beyond the Pillars of Heracles in the west, or the Mauryan empire in India—these areas lay outside the frontiers of the oikoumenē, and had no part in it. Even western Europe and the western Mediterranean were assimilated to it only through Rome. Contact between Magna Graecia or Sicily and the Greek East was, as we have seen, limited to commercial transactions, and from the time of the First Punic War these Greek enclaves became Roman fiefs: when Carthage’s hold over the West was broken, it was not by Greek action.

With unimportant exceptions, Hellenization meant the interpenetration of Greek and Oriental culture—that was certainly how Droysen saw it61—and where Greek rulers did not have the strong arm of Rome to maintain their institutions, they made a less lasting impression than is often supposed. As we have seen, the customary method of diffusion was by way of imposed rule, military settlements, commercial exploitation, by men who brought their language, culture, and administration with them, and enforced their authority by means of a mercenary army. Exploitation exacerbated poverty, so that resistance was often felt at all social levels, with an abused peasantry rallying behind a dispossessed aristocracy or priesthood.62 The conquerors’ artificial islands of culture were at first no more acceptable than a wrongly matched heart transplant. Again, the piecemeal Roman takeover from the beginning of the second century tends to obscure this.

The Ptolemies never cared about Egyptian civilization as such, even though they took over the Egyptian administrative system largely unchanged (p. 191), and regularly went through the mummery of a pharaonic coronation (placating the powerful priesthood was another matter); and the Egyptians rebelled against them whenever they could. In this connection we should note a remarkable document, the so-called Oracle of the Potter, an anti-Greek, anti-Macedonian nationalist manifesto from the early Ptolemaic period, which in apocalyptic language foretells the downfall of these hated and blasphemous foreign overlords, the destruction of irreligious Alexandria, the resurgence of Memphis as Egypt’s pharaonic capital. It thus seems likely to have been produced in secessionist Upper Egypt, about 200 (above, p. 304).63 Its appeal is to the downtrodden fellahin: it graphically portrays the starvation and misery of the chōra under Ptolemaic rule, and looks forward to a Golden Age to be ushered in by the restored Egyptian pharaohs, a regime so delectable that men will wish the dead alive once more. There is a resemblance here, at least in tone, to the somewhat later third Sibylline Oracle, produced perhaps around 150, in the reign of Ptolemy VI Philometor, by Jewish zealots: an incoherent attack on the Seleucids (especially for their activities in Palestine), the Romans, and Greek mores generally, which nevertheless reserves praise for Ptolemy himself, who had shown favor to the Jews. It is significant that by the mid-second century, with increasing assimilation of the middle and lower Greek social strata in Alexandria to Egyptian customs,64 this nationalist violence has largely subsided, and the new tension is between Graeco-Egyptian and Jew.65

The extent and passion of Iranian resistance—passive, militant, messianic, or proselytic66—to Alexander’s conquest and occupation can be gauged from the considerable body of surviving material (again, mostly prophetic and oracular) attacking it. Alexander is the Evil Invader; above all, like the Ptolemies in Egypt, he is presented as a blasphemous disrupter of religion. In both cases what has been destroyed is a system of divine kingship:67 for the Persians, part of the world order created by Ahura Mazda, and involving not only the priestly caste of the Magi, but also a long-established secular aristocracy, for whom the recovery of Achaemenid theocratic rule is a passionately held article of faith. This counterpropaganda, with nice irony, was disseminated in koinē Greek. As early as 320 we find a cuneiform Babylonian Chronicle attacking Antigonus One-Eye for his brutal depredations;68 Seleucus I took the hint, and got Babylonian support in consequence (312: above, p. 29). This was not the kind of atmosphere, to put it mildly, that encouraged acculturation across formidable religious and linguistic barriers.

Neither in Iran nor in India did Greek culture, arguably, leave any substantial trace beyond its own enclaves—certainly not in the literature, where Alexander and his conquistadors figure as “the demons with disheveled hair of the race of wrath.”69 Attic koinē did indeed, as we have seen, become a useful lingua franca in regions not too far from the traditional site of the Tower of Babel; but this was, first and foremost, for commercial and administrative reasons. As a medium for propaganda, on the other hand, it was, more often than not, employed against Graeco-Macedonian rule. Indeed, what has sanctified the koinē (in more senses than one), and given it by association a cultural réclame that it scarcely deserves per se, is, of course, its key role in the dissemination of Christianity.

It could be argued, with only minimal hyperbole, that the whole concept of Hellenization as a beneficial spreading of light among the grateful heathen was a self-serving myth, propagated by power-hungry imperialists, and rooted in the kind of contemptuous attitude (crystallized by Aristotle: above, p. 312) that saw Greeks as the embodiment of all intelligence and culture, while the rest of the world consisted of mere barbarians, that is, people whose speech was an unintelligible, non-Greek, ba-ba-ba. Alexander’s rape of the East rested very largely on this premise. Nothing is more eloquent of the enclave mentality than the export of Macedonian place names, wholesale, to northern Syria, so that the port of Seleucia-in-Pieria commemorates not only a ruling monarch, but also a local mountainous coastal range renamed after a loosely comparable site back home. The idea of a missionary crusade to spread superior culture among the unenlightened formed a useful propaganda adjunct to panhellenism, and was later popularized by Plutarch, who argued that those whom Alexander defeated were luckier than those who escaped him, since the former got the benefits of Greek culture and philosophy, while the latter were left to stew in their ignorant primitivism.70 Bullying people for their own good has a long and depressing history.

I wish I could share the optimism of the late Moses Hadas, who in his study Hellenistic Culture painted a roseate picture of the East’s enthusiasm for Greek ideas. Yet even he had to admit, significantly, that the enthusiasm was largely restricted to the “upper classes” (i.e., the professionally or socially ambitious), and that the Middle East was not nearly so anxious to see the light as the already more westernized Syro-Phoenician littoral.71 Those who wore Greek dress (and removed it in the gymnasium), who aped Greek accents, attended Greek plays, and dropped their pinch of incense on Greek altars, had good and sufficient reasons for their behavior, into which esthetic or moral considerations seldom entered. Genuine cultural conversions did undoubtedly take place; but they seem to have been very much in the minority. What we find instead, more often than not, is a steely determination to get on in the world: the eagerness of some locals to acquire Greek names should not necessarily be attributed to philhellenism.72 Modern parallels suggest themselves. Once again Cavafy has drawn us some marvelous pictures of the mixed motives governing such behavior.73

Hadas reminds us that even though the Bible was translated into Greek by Alexandrian Jewish scholars (above, p. 317), “we know of no case where a Greek work was translated into an oriental language,” the clear implication being that this is a proof of the superiority of Greek literature as such.74 The significance of this interesting fact is not, I think, quite what Hadas took it to be. Hostility, ignorance, and plain indifference played a large part in the matter. The hostility was not to Greek culture per se (though its secular nature did not appeal to fundamentally theocratic minds) so much as to foreign occupation and everything associated with it. Those few intellectuals who did take the trouble to investigate Greek culture tended to borrow its style (as Ezekial from Euripides) or scholarly techniques and methodology (as Jewish historians from the Museum of Alexandria) or formal logic (as the Pharisees from the Stoa or the Academy), husking out the theoretical insights and discarding the substance as irrelevant. Such attitudes should remind us that the Greeks brought with them neither a powerful proselytizing religion, like the Arabs, nor, like the Jews, a close-knit theocratic tradition of their own.75

To take your own superiority for granted does not necessarily, or even commonly, imply that you are altruistically eager to give others the benefit of it, especially when you are busy conquering their territory, exploiting their natural resources and manpower, taxing their citizens, imposing your government on them, and unloading their accumulated gold reserves onto the international market in the form of military loot. The main, indeed the overwhelming, motivation that confronts us in these Greek or Macedonian torchbearers of Western culture, throughout the Hellenistic era, is the irresistible twin lure of power and wealth, with sex trailing along as a poor third and cultural enlightenment virtually nowhere. Among all those in Alexandria who could boast aulic titles and high political, military, or even religious preferment, those in the arts and sciences are by a very long way the least prominent.76 While all three Successor dynasties patronized scholarship and the arts for reasons of prestige, such activities remained exclusively a court function, pursued by Greeks for the benefit of Greeks (above, p. 84). There is no hint of fusion or collaboration with the local culture: this omission is particularly striking in the case of Ptolemaic Egypt, since the (unwilling) host nation had a long and distinguished cultural history of its own.

Prosopographical research shows something over two hundred literary figures in Ptolemaic Egypt: all are foreigners.77 Even in medicine and science, where we would expect a higher proportion of native practitioners, out of more than a hundred known names only about a dozen are Egyptian (it is true, of course, and too seldom stressed, that an unknown proportion of these Greek names may in fact conceal Egyptian owners). There is not one Egyptian gymnasiarch or athlete; on the other hand, about one-fifth of the musicians, actors, dancers, painters, and sculptors known to us—again, about a hundred in all—have unmistakably Egyptian names. These statistics, fragmentary and uncertain though they are, nevertheless still tell their own story. The only cases of scholarly acculturation we know about are the compilations of a Manetho or a Berossos, Greek-language digests of local science or history made by compliant priests for their new overlords: Manetho’s history of Egypt to 323 was commissioned by Ptolemy II Philadelphos, while Berossos dedicated his account of Babylonia to Antiochus I. Amélie Kuhrt argues that both Manetho and Berossos “helped to make accessible the local ideological repertoires and historical precedents for adaptation by the Macedonian dynasties, which resulted in the formation and definition of the distinctive political-cultural entities of Ptolemaic Egypt and the Seleucid empire.” The first part of this claim is a euphemism for sedulous imperial bootlicking; the second is a wild exaggeration.78 When Callimachus wanted a really insulting tag for Apollonius, he referred to him as an Egyptian ibis (above, p. 201). Despite the low-level Egyptianization of Alexandrian Greeks from the early second century onwards (above, p. 316),79 the indifference of all Ptolemies before Cleopatra VII to the Egyptian language, let alone to what was written in it, testifies eloquently to a persistent, deep-rooted, all-pervasive cultural separatism in the upper echelons of Ptolemaic society.

It is also often asserted that this was a great age of exploration, another cliché that deserves closer scrutiny than it usually gets. Since transshipment at regular stages was the rule for ancient cargoes, and since, furthermore, very few travelers in antiquity (or indeed in any period before the nineteenth century) shared the passion of Flecker’s pilgrims in Hassan—“For joy of knowing what may not be known / We take the Golden Road to Samarkand”—but went abroad only in pursuit of handsome profits, it follows that their ignorance about what went on farther down the line remained profound. Trading embargoes such as that imposed by the Carthaginians on the western Greeks, who were effectively barred from Gaul, Spain, and the Atlantic, merely exacerbated this trend. As soon as the known boundaries are passed, the tall stories begin: tales of gold-digging Indian ants, of the Hyperboreans in the far north, up the amber routes (above, p. 207), of tribesmen with feet large enough to use as parasols to keep off the sun (Skiapods), or a penis reaching to their ankles, or born minus an anus, only acquiring this useful addition at puberty.80

Worse, such genuine explorers as there were tended to be disbelieved by the pundits at home. Seleucus I sent Megasthenes to visit the Mauryan emperor Chandragupta at Pataliputra (mod. Patna), on the Ganges: as a result of his journey Megasthenes wrote the best and most comprehensive account of India known to the ancient world, only to be dismissed as a liar by the later geographer Strabo.81 In much the same way Herodotus, earlier, had ridiculed the claim of certain Phoenicians to have circumnavigated Africa, because they “said what I do not believe, though others may, that while sailing round Libya [i.e., westward] they had the sun on their right”—a piece of evidence that in fact clinches the truth of their claim, and places their route clearly in the southern hemisphere, probably round the Cape of Good Hope. Apart from an abortive venture in the second century B.C. by Eudoxus of Cyzicus, this feat was not to be repeated till the Renaissance.82 Alexander believed to his dying day that the Caspian was an arm of the northern ocean.83 At some point between 320 and 240 a remarkable explorer called Pytheas, either eluding or postdating the Carthaginian blockade in the Mediterranean, crossed the Bay of Biscay to Ushant and Cornwall, and then circumnavigated Britain, making frequent forays ashore, and sailing as far north as the Faeroes (he mentions nights of 2–3 hours only, which gives a latitude of about 65°).84 At one point he entered a region where “there was no longer any separate land or sea or air, but a kind of mixture produced from these, resembling a jellyfish”: perhaps ice-sludge accompanied by an exceptionally nasty Norwegian sea fog.85

Again, the oddities of genuine experience excited disbelief. We find Polybius (of all people) sneering at Pytheas’s claims;86 but then Polybius had done some exploring outside the Pillars of Heracles himself (above, p. 279), and may have disliked competition. Pytheas is also unusual in that, if we discount the lure of the Cornish tin mines, he seems not to have been following a commercial route. He was a skilled astronomer and mathematician, who investigated tides, and whose calculations of latitude achieved unprecedented accuracy.87 Most of the exploration done in the Hellenistic period, however, followed the lines of age-old trade routes, and very often (because of the transshipment principle) failed to pursue even them far beyond the early staging posts. The fantastic geography in Book 4 of Apollonius’s Argonautica reveals a fundamental ignorance of the rivers of central and northern Europe (above, p. 213). Despite Alexander’s expedition and Ptolemaic exploration of the sea routes to the East, it was not until the reign of Tiberius that a Greek merchant, one Hippalos, caught on to the simple secret of the Indian monsoon winds (known, and kept secret, by Arab middlemen for centuries): that from May to October there was a steady prevailing wind from the southwest to carry a ship to India, and that from November to March it reversed itself, and blew with equal steadiness from the northeast.88

The conflict of Seleucid and Ptolemaic rulers over Syria did not—predictably— lack its element of commercial competition (cf. p. 372). The trade routes from the East mostly converged at Seleucia-on-Tigris:89 they included the sea lane up the Persian Gulf, and the overland caravan routes from the Hindu Kush. From here, by two alternative routes, they reached the Mediterranean at Antioch’s port of Seleucia-in-Pieria. From Antioch consignments were dispatched through Anatolia to Ephesus by way of Tarsus and Apamea, along the western section of the old Achaemenid royal road. This road was nominally under Seleucid control, but at various times the Ptolemies disrupted it (Ephesus itself changed hands more than once), until Antiochus III’s victory at Panion in 200 finally eliminated Ptolemaic competition from this area altogether (above, p. 304). The Ptolemies thus became dependent exclusively on the southern sea route from India, which made port at Aden. From Aden goods were transported by caravan north to Palestine or Alexandria. However, the loss of Coele-Syria made the northern end of this route equally problematic of access; so we find second-century Ptolemaic traders moving south in search of a link route that would bypass Arabia altogether, from some point along the shores of the Red Sea.

The Ptolemies were also in search of what had become an increasingly highly valued arm in ancient warfare: elephants. (Whether they were in fact worth the time, money, and trouble expended on them is another matter altogether.) The elephants that the Ptolemies’ hunters rounded up in what is now Somalia were not the large African bush elephant, but the smaller forest elephant:90 at Raphia, in 217, the huge Indian elephants of Antiochus scared them off even before battle was joined.91 Inscriptions and literary sources alike suggest exclusively commercial reasons for opening up this route south and east of Egypt; the same is true of Seleucid control over the Oriental caravan routes. We hear of both dynasties commissioning explorers, but only to secure or establish openings for profitable trade. The scientific curiosity that (perhaps through Aristotle’s urging) stimulated Alexander to take geographers and botanists on his expedition is almost wholly absent here. Yet at the same time geographical theory was advancing. By about 300 Dicaearchus of Messene had produced a map of the known world embodying, in crude form, the principles of latitude and longitude; so, somewhat later, did Eratosthenes, Apollonius’s successor as chief librarian in Alexandria, aided by a surprisingly accurate formula for measuring the circumference of the earth (below, p. 480).92

If Greeks and Macedonians did not promote their culture with the object of converting their new subjects to Hellenism, at least their post-Alexandrian diaspora carried that culture—certainly its more visible and socially indispensable elements—to the four corners of the Mediterranean world and beyond, so that there developed (for example) something of an international style in Greek art. It has been claimed that “a middle-class Greek, settling down in the Fayyum . . . might hire Egyptian workmen to decorate his walls with murals—but the pictures themselves would be crude imitations of what was being painted at Athens or Syracuse or Antioch.”93 The basic inspiration remained Greek. Generalizations in this area are dangerous. The evidence is patchy, while those with the money to commission murals obviously made sure that they got what they wanted, and some patrons will have had more adventurous taste than others. But the phenomenon described certainly existed: my impression is that it was commoner in the third century than later. This would agree with the patterns of absorption we have noted, which show (in Egypt as elsewhere) a slow progressive surrender to local influences from about 200 onwards.

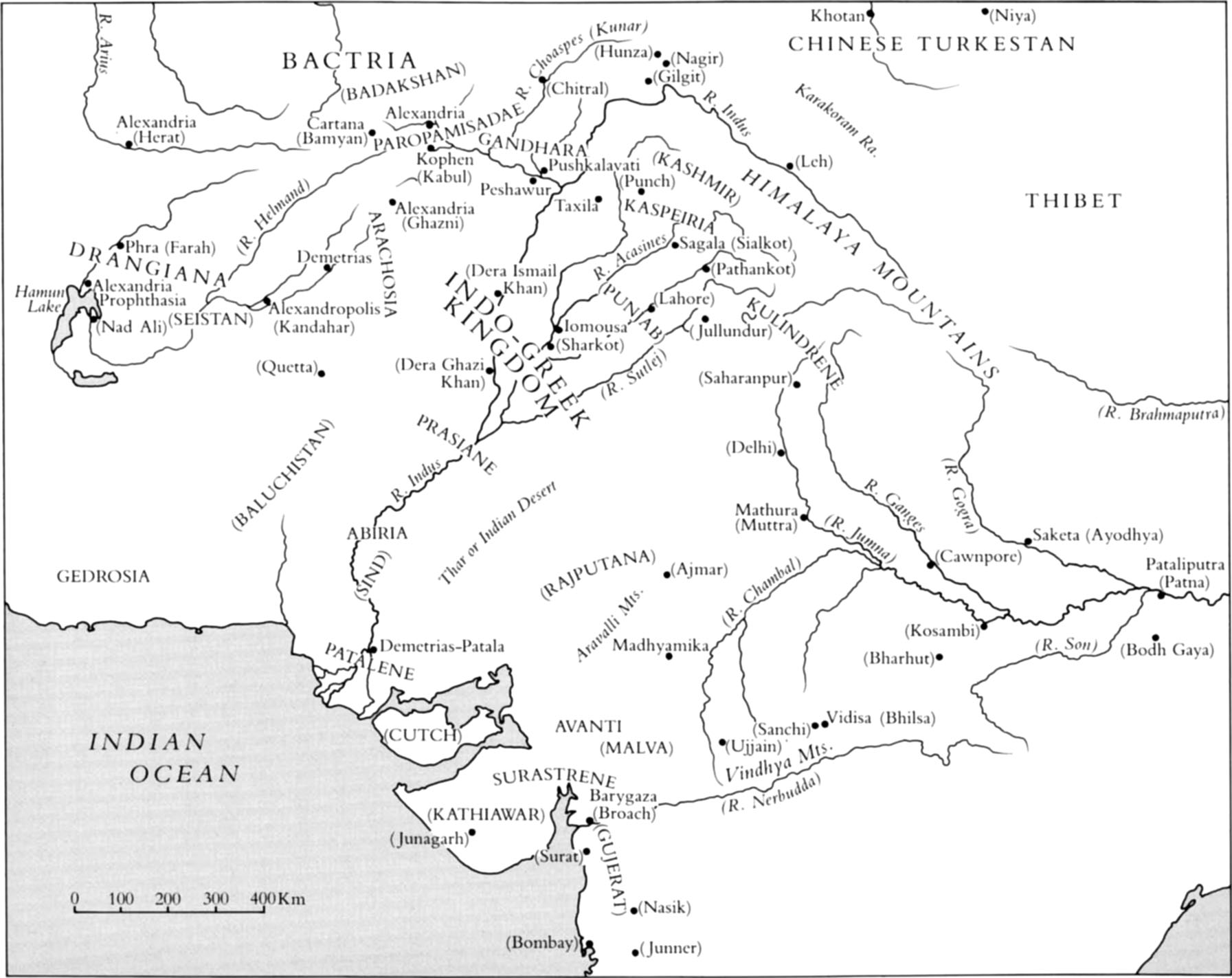

Perhaps the most extraordinary example of Greek enclave culture—finally absorbed by something larger than itself—is that of the isolated Greek kingdoms in Bactria and India. For over two centuries, beginning with the renegade Seleucid satrap Diodotus shortly before or after 250, a series of more than forty Greek kings ruled in the East, from Bactria to the Punjab. There are a few scattered literary references—we have already seen how Antiochus III besieged Euthydemus for two years in Zariaspa (above, p. 295)—but most of the story has been pieced together from these rulers’ self-promoting and highly idiosyncratic coinage. Though there is a great deal of scholarly dissension concerning the chronology, relationships, and conquests of individual monarchs, the overall picture is clear enough.94 Greeks had been settled in Bactria by the Persians long before Alexander left colonists there:95 some were time-expired mercenaries, who chose these fertile uplands rather than the unpredictable future of a retirement in Greece. They also formed a handy buffer against the constant threat of incursion by northern nomads (above, p. 295).96 Alexander, recognizing the difficulties inherent in a Bactrian satrapy, earmarked a remarkably large body of troops for the policing of the area (above, p. 9). Two years before his death the Greek colonists revolted (325),97 and in 323 it took a major campaign by a picked body of Macedonian veterans to subdue them.98 At the settlement of Triparadeisos, in 320 (p. 15), the satrap placed in charge of Bactria was, significantly, a Cypriot Greek, Stasanor. The choice arguably reflects an attempt to conciliate these restless and intractable Greek settlers, though we are also told that no Macedonian would touch the job. Stasanor’s presence certainly quietened things down, but at the price of encouraging a separatist movement. By 316, indeed, Stasanor was so well entrenched in his bailiwick that not even Antigonus One-Eye would attempt to shift him.99

A few years later, after his capture of Babylon, Seleucus I reconquered Bactria:100 clearly the only way to hold it was by force of arms. Whether in the circumstances he continued the practice of encouraging Greek settlers101—the prime cause of trouble in the region—seems highly doubtful. At all events, shortly before or after 250 yet another satrap, Diodotus, finally broke away from the Seleucid empire, and established a Bactrian kingdom. Bactria was a frontier province, and it must have occurred to Diodotus, very early on, that he got little from his Seleucid overlords in exchange for the tribute payments that they were seldom powerful enough to enforce. Even so, as in the similar case of Pergamon (p. 168), he seems to have continued to acknowledge Antiochus II’s sovereignty on his coins long after his de facto secession.102 The large number of Greek colonists in Bactria gave his rule powerful support, and created an ethnic enclave of a most unusual sort.

There has been much debate as to whether the Greek empire of Bactria and India was, in essence, a fifth Hellenistic state, or rather “part of the history of India.”103 The simple answer is that it began as the first and ended by being absorbed into the second (cf. above, p. 322). Just how persistent Greek separatism was has been strikingly demonstrated by a decade and more of excavation at Aï Khanum. This city (“Lady Moon” in Uzbek) lies at the confluence of the Oxus (Daria-i-Panj) and Kokcha rivers, on the northern Afghan frontier with Soviet Russia. It occupies a natural strategic site, well placed to guard the northeastern approaches to Bactria.104 Founded about 329/8, during Alexander’s campaign in the upper satrapies, it finally succumbed, about 100, to a barbarian incursion from across the Oxus (in December 1979, by one of history’s coincidental ironies, its French excavators were cut off from their site in precisely the same way) and saw its desecrated temple turned into a Kushana storage magazine.105

Despite its remoteness, Aï Khanum was in every respect a Greek city throughout. The great palatial complex with its peristyle courtyard, the funerary cult shrine (hērōön), the lush Corinthian capitals of the hypostyle hall—though the hall itself is an interesting Achaemenid throwback—the pottery, the bronze and terra-cotta figurines, perhaps above all the Delphic maxims inscribed, in Greek, on a base in the hērōön (copied at Delphi, set up, and paid for by a loyal globe-trotting citizen), all form “a stunning testimony to the fidelity of these Greek settlers of remote Bactria to the most authentic and venerable traditions of Hellenism.”106 That verdict was given in 1967: subsequent seasons of excavation have not merely confirmed but intensified it.

The area was peaceful and well guarded: Aï Khanum’s long-undisturbed state is a tribute, in this wild frontier region, to highly efficient policing. Probably Euthydemus made full use of the famous Bactrian cavalry to keep the Saca hordes in check: he was able to raise no less than ten thousand horsemen against Antiochus.107 Outside the walls Paul Bernard and his team found not only a large funerary mausoleum of Hellenistic type,108 but also a wealthy Greek colonist’s villa, probably the home of some landowner who lived on, and by, his estates, using local labor in much the same way as was done in other parts of the Seleucid empire.109 The gymnasium or palaestra covered an area of nearly a hundred square yards.110 There was a beautiful public fountain with carved gargoyles and waterspouts in the form of lions’ and dolphins’ heads.111 A temple, a palace, an arsenal: these were predictable enough;112 on the other hand, the discovery of a Greek theater beside the Oxus came as something of a surprise, a striking symbol of Hellenic cultural vigor in this remote region.113 It may not suffice to justify Plutarch’s romantic picture of Persian or Gedrosian children happily declaiming the choruses of Sophocles,114 but at least it forms a logical companion to the fragments of what appears to be a post-Aristotelian philosophical treatise,115 not to mention a sophisticated sundial.116

Behind its constantly renovated city walls, well defended and ethnocentric, the enclave of Greek Aï Khanum held the outer world at bay.117 The isolation, however, was never total, and indeed by the end Aï Khanum had become more effectively cut off from the Greek West than from the indigenous culture of Bactria. One arresting symptom of this severance is the large pebble mosaic, dated to about 150, found in the palace bathing quarters.118 It is not only the poor, provincial quality of the execution that attracts attention—large, coarse pebbles, a total absence of defining lead strips and even of black pebbles set to create outlines—but the remarkable fact that elsewhere in the Greek world pebbles had, for a century and more (i.e., just about since the establishment of the Bactrian kingdom) been replaced by cubes (tesserae), which made possible a far more subtly modulated technique. This suggests that the mosaicists who went east handed down their skills without any fresh infusion of outside talent, finally suffering a degeneration comparable to that we find, over a similar period, in the gold staters originally struck by Philip II, then copied and recopied as far afield as Gaul and southwestern England, till the quadriga and charioteer on the reverse became a meaningless jumble of lines and blobs.119 At the same time, local influences can be detected ab initio in the architecture (e.g., the hypostyle hall) and the visual arts, growing, as we would expect, progressively stronger with time.120 A non-Greek temple was found outside the walls.121 A silver-gilt medallion of Cybele in her chariot, from the mid-third century, already reveals a subtle fusion of Greek and Oriental elements, with the latter ultimately predominant.122

After Diodotus I’s death, perhaps as early as 248,123 his son of the same name succeeded him, and ruled till about 235, when he was killed during a coup. Its leader was Euthydemus, in all likelihood a relative of Diodotus, and perhaps the satrap of Aria and Margiana, who thus founded the second dynasty of Graeco-Bactrian kings.124 He enjoyed a long reign (it was toward the end of it that he stood off Antiochus), but details are lacking. His son Demetrius I (r. ca. 200–190),125 a strong, heavy-jowled man portrayed wearing the elephant-scalp headdress (as a conqueror of India), and possibly married to a daughter of Antiochus III, crossed the Hindu Kush into the Punjab, and established himself at Taxila;126 he had already made inroads on the old Seleucid satrapies around the Caspian.

In India now as well as Bactria, these Greek dynasts—Demetrius, the great Menander, Euthydemus, and the rest—maintained their improbable rule. “Against all imagining, almost entirely cut off from the Greek world, for more than a hundred and fifty years they and their descendants ruled in western India. They lived, spoke and thought as independent Greek kings long after Greece itself had fallen wholly under the power of Rome.”127 Bactria held out till about 140, when the last regnant Graeco-Bactrian king, Heliocles I, went down fighting the Saca hordes from the Asiatic steppes, leaving his descendants as a landless dynasty. The Indian kingdom persisted almost another century; then, about 55, its king Hermaeus likewise vanishes from history, to be replaced by the Saca chieftain Azes I. Yet Menander, the Buddhist convert, was the only one of these legendary rulers to survive in Indian literature, under the name of Milinda: there is, surely, a moral of a sort to ponder here. Far more important than his prowess as a warrior was his status as a sage and a thinker, who had embraced Eastern ways: when he died, he was revered as a saint, and his ashes were divided between the chief cities of his kingdom.128 Whatever impressed Menander’s Indian subjects, it was not his superior Greek culture.