By defeating Eumenes, Antigonus had consolidated his grip over a vast area extending from Asia Minor to the uplands of Iran. The fiction of special commands under the kings was still maintained, but Antigonus began to act uncommonly like an independent monarch. He removed Peithon from his office as satrap of Media, and had him liquidated, on a charge—possibly true—of planning revolt. To replace him he reverted to Alexander’s old pattern of appointing a native satrap, in this case one Orontobates, but he also installed a Macedonian garrison commander.1 The satrap of Persia, Peucestas, another of Alexander’s old personal friends, had, uncharacteristically, gone native in dress and custom, and was immensely popular locally as a result: Antigonus discreetly kicked him upstairs with the promise of high office, and made sure he was kept from then on at headquarters, where he could not get up to any mischief.2 Other veteran officers were executed on various pretexts, or killed while attempting alleged insurrections.

More alarming still were Antigonus’s systematic raids on the treasuries of Ecbatana, Persepolis, and Susa, from which he removed a total of no less than twenty-five thousand talents.3 Nor was the lesson of Eumenes’ betrayal lost on him. The Silver Shields, who had sold Eumenes to Antigonus in return for their loot, could never be trusted again. A new mercenary age was dawning, in which an army would regularly sell itself, as a matter of course, to the general who defeated it; but even among mercenaries the Silver Shields were a special case. Antigonus posted the more reliable of these veterans to his phalanx brigade, and then had a quiet word with Sibyrtios, the satrap of Arachosia, a tough frontier region south of the Hindu Kush, on the borders of modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. In return for confirmation in his office, Sibyrtios was to dispose of the hardest cases among the Silver Shields. They were to be posted to Arachosia, and sent out, a detachment at a time, on garrison, scouting, or other front-line duties in which they were sure to be killed.4 Finally, the axe seemed about to fall on Seleucus, the satrap of Babylonia. Ordered to give an accounting of his office by Antigonus (who had clearly learned something from Perdiccas’s methods), Seleucus prudently fled to Ptolemy in Egypt (late summer 315).5

Antigonus was thus left controlling virtually the whole of Alexander’s Asian empire; he was, further, supported by numerous mercenaries, and could afford to pay them on a long-term basis. Needless to say, his high-handed moves caused great alarm among his fellow marshals. Seleucus lost no time in warning Ptolemy—not to mention Cassander in Macedonia, and Lysimachus in Thrace—that Antigonus was purging all Alexander’s old officers, had acquired immense wealth, “and as a result had displayed overweening arrogance, so that his ambitions now embraced the entire Macedonian kingdom.”6

Meanwhile Antigonus himself marched down into northern Syria (315/4). On the way he raided another ten thousand talents from the treasury at Cyinda, in Cilicia; since he held the kings’ commission as commander-in-chief, it was hard to argue with him (whatever counterclaims Cassander might make in Greece), and the Persians were already treating him as “the acknowledged lord of Asia.” He also received eleven thousand talents in the form of annual tribute.7 In Syria he was met by envoys with an ultimatum from Lysimachus, Ptolemy, and Cassander.8 He was to restore Seleucus to his Babylonian satrapy; he was to surrender Syria to Ptolemy, and Hellespontine Phrygia to Lysimachus. This last was a particularly outrageous condition, since it would have given Lysimachus—whose titular claim to this area was nonexistent—a stranglehold over the Hellespont. There may also have been a clause (the text of Diodorus is uncertain) requesting the cession of Lycia and Cappadocia to Cassander. Antigonus was, further, to share out all treasures taken since the death of Eumenes. He gave the envoys, not surprisingly, “a somewhat rough answer.” His flat rejection of their terms was inevitable: it also meant war.

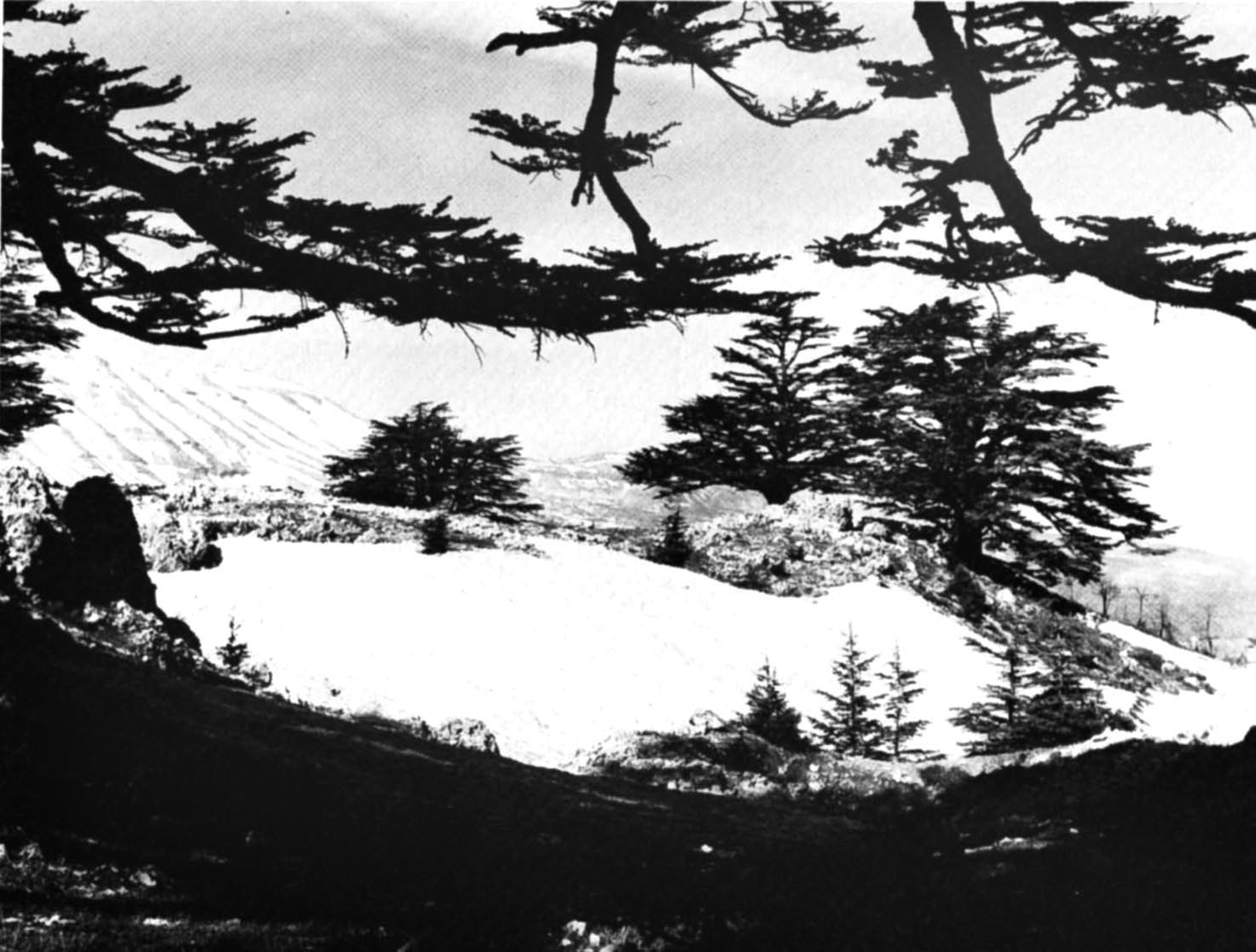

Confident and aggressive, Antigonus pressed on south to Phoenicia.9 If there was to be war, he would be ready for it. His vast cash reserves—over 45,000 talents—dwarfed those of his opponents. He had one great weakness, the lack of a fleet: Seleucus could—and did—sail past his camp with impunity. Nothing daunted, Antigonus now set up shipyards at Tripolis, Byblos, and Sidon, as well as on the Cilician coast; he also made a deal with the Rhodian government to build vessels for him from imported timber (see p. 32).10 Like Alexander, he bivouacked near Old Tyre, and laid siege to Tyre itself, though to begin with he made little headway against the citadel; that was strongly held by Ptolemy’s troops, many of them formerly in the service of Perdiccas. Antigonus secured alliances with some of the princes of Cyprus, a counterweight against Nicocreon and other local kings, who since 321 had had treaties with Ptolemy.11 He stormed Joppa and Gaza. He sent his nephew—another Ptolemy—to settle affairs in Cappadocia and to guard the Hellespont against a possible crossing by Cassander. He even sent a mission to Polyperchon in the Peloponnese,12 naming him generalissimo there, for what that was worth,13 sweetening the offer with a thousand talents (which by now he could well afford), and encouraging the old commander to carry on the war against Cassander in Greece. He set up a system of beacons and dispatch carriers throughout the eastern Mediterranean to speed up communications.14 His energy and determination were boundless.

Perhaps most important, from Old Tyre Antigonus issued a public political (and, from his own viewpoint, juridically binding) manifesto before his assembled troops, who gave it a semblance of Macedonian legitimacy by acclaiming it.15 The main points of this so-called Decree of the Macedonians were as follows. First, Cassander—who, Antigonus asserted, had murdered Olympias, married Philip II’s illegitimate daughter, Thessalonike, by force, and was trying to make a bid for the throne of Macedon—was to be declared a public enemy unless he destroyed the cities of Cassandreia (Potidaea) and Thebes, both of which he had rebuilt,16 released Roxane and Alexander IV “and gave them back to the Macedonians” (whatever that meant; presumably to Antigonus himself and his supporters), and “in short, obeyed Antigonus, the properly appointed general, who had taken over the guardianship [epimeleia] of the monarchy”—a peculiarly brazen claim, since young Alexander IV and his mother had been in Cassander’s keeping ever since 317/6 (see p. 20). Second, all the Greek cities were to be free, autonomous, and ungarrisoned: this clause applied both to those on the mainland and to the cities of Asia.

It is this second provision that was of real significance. The perennial, and virtually insoluble, problem it enshrined was that of somehow reconciling the cities’ passion for self-determination with the autocratic powers exercised by the great Hellenistic monarchies.17 Polyperchon had handled the question by means of a reversionary amnesty decree from which the words “freedom” and “autonomy” were conspicuously absent (see p. 18). Antigonus’s gesture, then, was something new. How far he and his son Demetrius after him were sincere in their championship of Greek freedom is debatable. The propaganda value to them, and the embarrassment to their rivals (Cassander in particular), were both immense. What was more, the good will of the Greek cities not only eased the collection of revenues, but also made available a vast pool of skilled labor. Both rulers, for whatever reason, held fast to the new slogan throughout their lives. We should note that neither freedom nor autonomy meant exemption from taxes or tribute (aphorologēsia): it was the Roman general Flamininus who made that welcome addition to the formula (see p. 311).18 Autonomy was indeed synonymous with polis rule, and a vital condition for its survival;19 but the anomalous, not to say paradoxical, position of these cities in the context of a bureaucratic and authoritarian central government meant, in the vast majority of cases, that their much-touted freedom was illusory, a matter of empty honorific titles, parochial offices, municipal privileges, votes that lacked power, form without substance. There were exceptions (Rhodes is a notable instance, but Rhodes was a special case: see p. 378); exceptions, however, they remained.

As soon as he heard what Antigonus had done, Ptolemy issued (fall 313) a similar proclamation, “wanting the Greeks to know that he, no less than Antigonus, had their autonomy in mind.”20 There is an interesting contrast here. Antigonus could make his offer look plausible enough, since the Greek cities of Asia were already free, democratic, and ungarrisoned. On the other hand, Cassander, Lysimachus, and Ptolemy all held cities down with garrisons and oligarchies. It is interesting to speculate just why Ptolemy—who was, after all, Cassander’s ally—should have come out with so embarrassing a pronouncement at this point. The most likely explanation is, Ptolemy had already foreseen that his ultimate adversary would be whoever triumphed in the confrontation between Cassander and Antigonus:21 no bad thing, then, to furnish himself good propaganda as a defender of liberty well in advance.

Needless to say, none of these ambitious rivals hesitated for one moment to trample on every Greek liberty in sight when the situation called for tough or emergency measures. Even if we concede Antigonus, as I think we must, both consistency and sincerity in his policy of freedom for Greece, it still remains true that his prime concern was the strategic consolidation of his own power.22 In furtherance of this aim he now promoted, as a counterweight to Cassander’s Athens, the so-called League of Islanders (314?). This organization drew its membership from the Cycladic islands of the central Aegean, and had its center on Delos.23 (Whether Delos itself was a member is disputed, though the island remained under Antigonid control until 286.) The League offered useful reinforcement to Antigonus’s still-weak naval arm: there is evidence that the islanders defended their territories against his enemies. At the same time Antigonus kept up a flow of cash, troops, and agents into Greece, attempting to rouse the Greek cities against Cassander. Finally, after a lengthy siege, he also forced the capitulation of Tyre (June 313).24

The first round of the struggle lasted until 311. Antigonus, like Perdiccas in 321, found himself fighting a war on two fronts, around the Hellespont and in Syria. There was, as well, inconclusive activity in mainland Greece and in parts of the eastern Mediterranean, where Antigonus and Ptolemy vied for control of Rhodes and Cyprus. Revolts in Cyprus and Cyrenaica kept Ptolemy busy until 312,25 but he was then persuaded by Seleucus—impatient to recover his command at Babylon—to chance a showdown against Antigonus’s son Demetrius in the Gaza Strip. Demetrius, young, tall, exceptionally handsome, was married to Craterus’s widow, Phila (see p. 15), one of those brilliant, forceful women whom we meet again and again among the Hellenistic ruling classes.26 At Gaza he proved no match for Ptolemy (late 312),27 losing five hundred of his best troops killed and eight thousand captured, with Ptolemy’s war elephants wreaking havoc among his cavalry.28

This victory gave Seleucus the chance (borrowing troops from Ptolemy for the purpose) to return to his fief in the East. Encouraged by oracles and dreams that hailed him, Macbeth-like, as a future king, Seleucus, in quick order, recaptured Babylon, won over Media and Susiana, and began writing to Ptolemy with something very like royal panache about his achievements.29 Ptolemy himself did not capitalize on his victory at Gaza. The news of it at once drew Antigonus down to Syria from Asia Minor; but Seleucus’s successes made an immediate campaign undesirable. Antigonus was reunited with his son Demetrius, who had extracted himself from his defeat with reasonable skill, and a general peace began to look attractive to all involved—not least to Ptolemy, who had no liking for another round in Syria with Antigonus. The terms of the treaty (311) were little more than a rationalization of the status quo.30 Cassander was to be “general of Europe” until Alexander IV came of age: the royal succession was, officially at least, still being kept alive, though the signatories to the treaty dealt with each other as de facto independent rulers, and Cassander was shortly to lay the whole pious fiction to rest—along with the surviving Argeads. Lysimachus was confirmed in Thrace, Ptolemy in Egypt and the adjacent regions, while Antigonus was to be “first in rank in all Asia,” a significantly vague phrase31 that took no account of Seleucus’s aggressive campaigning in the eastern satrapies.

Seleucus, in point of fact, now very much master of his own fief again, was not a party to the peace treaty at all: he and Antigonus remained at war until 309/8.32 Nor, we may note, was Polyperchon, that blunt old royalist officer out of his depth in these new power games, but doing his level best to learn the tricks of blackmail, murder, and betrayal along with his juniors. Bribed by Antigonus, as we have seen, with the offer of the command in the Peloponnese against Cassander, he found himself deserted by his own son Alexander (who went over to Cassander’s side: 315/4?), and seems to have followed him in 313. We have not yet heard the last of him.

Finally, by the peace of 311 the Greek cities were formally declared autonomous, and were required, on oath, to preserve each other’s freedom at need. We possess an official (and in places carefully vague) letter from Antigonus to the city of Scepsis, in the Troad, touting the peace as a triumph, stressing his concern with the citizens’ freedom, and, predictably, making no allusion to Demetrius’s humiliating defeat at Gaza.33 (Scepsis in return promptly offered Antigonus, now over seventy, divine honors.)34 The oaths sworn by all contracting parties may well have persuaded Antigonus that he could use the Greek poleis as a powerful extra political or military force if he could claim infringement of the treaty by any of his rivals. He would, on the other hand, have no hesitation about taking a tough line with any city that used its freedom against him. In any case, the treaty lasted almost no time at all, and the freedom clause proved to be little more than a political chimaera. All the marshals by now controlled various Greek cities—Antigonus in Anatolia and the Aegean, Lysimachus in Thrace, Ptolemy in Cyrenaica and on Rhodes and Cyprus, Cassander in Greece itself. None of them would ever let these power bases revert to true independence: in other words, each signatory to the treaty would have a fine excuse for war whenever he needed it. Once again, despite the preservation of the regency, it was clear—clearer than ever—that there were five virtually independent fiefs, those of Ptolemy, Antigonus, Lysimachus, Cassander, and Seleucus. Yet at least three of the five lords—Antigonus, Lysimachus, Seleucus—still nursed the ambition of winning the whole of Alexander’s empire. In this they were, to some extent, abetted by the treaty of 311, with its diplomatic fiction of an undivided inheritance under Alexander IV.35 It was to be another decade before that dream was finally laid to rest.

For both Antigonus and Ptolemy, in fact, the peace of 311 was no more than a truce, a breathing space. Ptolemy was eager to recover the whole satrapy of Syria, and with it Phoenicia, where Demetrius had been quietly reestablishing his power. Though Antigonus wanted to take advantage of peace in the West to deal with Seleucus, he remained in hot competition with Ptolemy for the islands and ports of the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean. By 310 Ptolemy was accusing Antigonus of infringing on the freedom of the Greek cities of Cilicia,36 while Cassander, tired of playing royal guardian, brought some honesty into the power struggle by having the young Alexander and his mother, Roxane, executed. (Theories that they were only executed much later or that Cassander contrived to keep their deaths secret until 306 [!] lack persuasiveness.)37 From now on, as Diodorus says, “all those who ruled nations or cities nursed royal hopes.”38 But the Argead mystique died hard, and it was four years before a new claim to kingship, based primarily on achievement, emerged and was upheld. Antigonus, with opportunistic cynicism equal to Cassander’s, furnished old Polyperchon with one final ace to play in the royalist stakes: Heracles, Alexander’s illegitimate son by Barsine, now about sixteen years old.39 Polyperchon, with this new claimant to the throne in tow, made a spirited bid to invade Macedonia. Cassander, who had not cut short the legitimate bloodline in order to have his well-laid plans disrupted by a bastard, promptly sized up Polyperchon’s limitations with uncommon finesse, and did a deal with him. He confirmed him in the Peloponnese, and left him the empty title of general (stratēgos); what he asked in return was the murder of Heracles.40 Polyperchon duly obliged, and from that moment, like the old soldier he was, faded away. His bargaining counter gone, he languished in subordinate positions, and by 302 was dead; how or when we do not know. But with Heracles’ death, and the murder—on Antigonus’s orders—of Alexander’s marriage-hunting sister, Cleopatra, in Sardis a year later (309/8),41 the Argead line of Philip and Alexander was finally at an end. The time was ripe to recognize a few new royal dynasties; but they still took their time in appearing.

Antigonus’s attempt to deal with Seleucus failed, and that failure led to the old marshal’s undoing.42 Antigonus’s general Nicanor met Seleucus in a great battle: we can pinpoint neither its exact location nor its date, but it was somewhere in the eastern satrapies about 309/8, and Seleucus was victorious. If 312 was afterwards remembered as the first regnal year of the Seleucid dynasty43—being the year in which Seleucus retook Babylon from Antigonus’s forces—then this victory finally assured the dynasty’s survival, even though Seleucus did not officially assume the diadem till 305. Antigonus was forced to abandon any hope of recovering Alexander’s eastern conquests beyond Anatolia. He seems, indeed, to have made a nonaggression pact with Seleucus, since from 308 Seleucus was in conflict with Chandragupta (known to our Greek sources as Sandrakottos), the Indian founder of the Mauryan empire, and in 303 ceded him the satrapies of Gandhara, eastern Arachosia, and Gedrosia in exchange for intermarriage rights and a gift of five hundred war elephants.44 When the final showdown came between Antigonus and his rivals, those elephants played a crucial part in securing the victory (see p. 34).

The struggle between Antigonus and Ptolemy for the control of the Mediterranean continued. Ptolemy—who seems earlier to have been at least in diplomatic communication with Seleucus45—accused Antigonus of garrisoning supposedly free cities (310), though at the same time he was setting up a command post of his own on Cos. Antigonus, ignoring the complaint, strained every nerve to build up a large fleet.46 Events in the years between 310 and 306 are confusing, since Cassander’s deal with Polyperchon produced, by way of reaction, a brief alliance between Ptolemy and Antigonus, the main rivals. This, however, was a mere expedient aberration. Ptolemy made an abortive invasion of the Peloponnese (308), his sole venture on the Greek mainland,47 gaining little except some garrisoned keypoints near the Isthmus (Corinth, Sicyon, Megara): bad propaganda, in any case, for a self-styled liberator of Greece. Soon afterwards Antigonus sent Demetrius to free Athens from Cassander, which he did (307), to freedom-loving cheers from the populace. The city was now refortified and strengthened in anticipation of the coming conflict with Macedon (the so-called Four Years’ War, 307–304).48 Though an attempt at this time to organize the Greek states into an anti-Cassandran league, reminiscent of that set up by Philip II, proved premature, Athenians had no qualms about offering their new earthly savior divine honors—perhaps because of the timber for a hundred triremes that he promised them from Syria. Had Cassander, as seems likely, cut off Athenian imports of Macedonian lumber? At all events the wood (probably Cypriot pine) was delivered, and Athens paid 14,040 drachmas for its transport.49 The puppet dictator Demetrius of Phaleron (see p. 48) went into exile, and a democratic government (but one under Antigonus’s control) was set up.

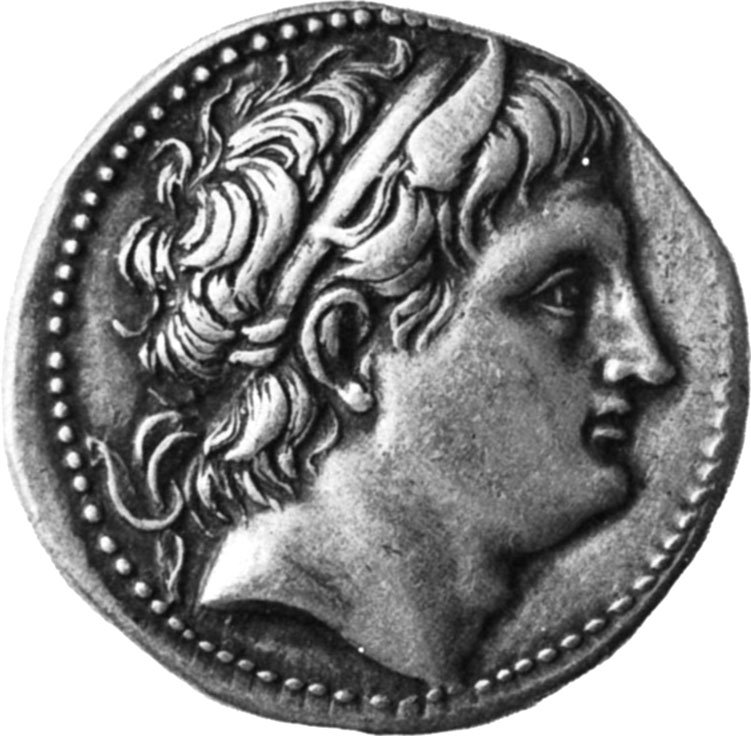

This venture, however, marked the limits of the cooperation between Antigonus and Ptolemy. Warfare broke out between them again almost immediately, first off Cyprus, where Demetrius, fresh from the fleshpots of Athens, equipped with new, large vessels, and posing once more as a liberator,50 inflicted a crushing and immensely significant defeat on Ptolemy’s forces (306); and then in Egypt, where Ptolemy, rallying gamely from the greatest setback of his career, was lucky to beat off a full-scale invasion.51 He might write jauntily to his allies, Cassander in particular, “about his successes and the mass of deserters who had joined him,”52 but he made no mention of Cyprus, which for the next decade passed under Antigonid control. Demetrius struck coinage at the Cypriot mint in Salamis that showed Poseidon wielding his trident and, on the reverse, Nike (Victory) alighting on the prow of a trireme.53 The point was well taken.

Demetrius’s victory in Cyprus also marked the final step in the emergence of the independent Hellenistic kingdoms of the Successors, the establishment of new royal dynasties.54 The delay in taking such a step (it was, after all, four years since the murder of Alexander IV) has often been remarked, and is indeed significant. It is surely to be explained by the profound differences observable between the old Macedonian national and territorial kingship and the new reliance on simple military achievement: the Ptolemies and Seleucids had been brought up under the old regime, but they claimed their thrones on the new terms established by Alexander. The change took time to work out, let alone get used to. But now, to celebrate their Cypriot victory, which was made the clear justification for such pretensions, Antigonus took the title of king (basileus), and bestowed it also on his triumphant son. The affair was skillfully stage-managed. From now on both wore the diadem and the royal purple. Thus, even if Antigonus did not lay claim to the heritage of Alexander, which is debatable,55 he at least formally established the concept of the Antigonid dynasty, and on the basis of military achievement rather than territorial claims. Not to be left behind, within a year or so both Ptolemy and Seleucus had each also proclaimed himself king (305/4);56 so, apparently, did Lysimachus. Even Cassander, despite Plutarch’s reservations as to whether he claimed the title officially,57 is referred to as “King Cassander” on coins, and is described on a bronze statue base at Dion as “Cassander, King of the Macedonians.”58 That he was now recognized as king seems certain (306; see below). At last, after almost two decades, Alexander’s officers were reaching out beyond his gigantic shadow.

It is usually said that, of all these crowned heads, only Antigonus still dreamed of ascending the throne of a united empire, and thus fiercely contested the claims of his fellow monarchs. It is true that not only Antigonus, but also Demetrius, refused the title of king to the rest; it is also true that the Antigonids persisted in claiming kinship with the Argeads.59 But while the others—if territorial claims came into it at all—were primarily serving notice of ownership on specific areas (e.g., Ptolemy in Egypt, Lysimachus in Thrace), and were thus quite happy to recognize one another’s titles, did that mean that they would refuse imperial supremacy if the chance offered itself? And were they not, in any case, anxious to avoid being thought inferior to Antigonus? As we shall see, the dream of empire could still overpower Lysimachus and Seleucus, even if they were ready, as good pragmatists, to settle for shorter horizons until, or unless, fortune smiled on their endeavors.60

The future was to lie with the separatists; but Antigonus, for one, still cherished greater hopes. After all, his kingship at present remained a rather elusive concept, and his son Demetrius was to be for some years a king virtually without a physical kingdom. The title “king,” not least in the East, could still compel obedience in a way that other names could not;61 but these new monarchies seem not only to have been predicated on the dynasty rather than the territory, if any, that it controlled, but also to have been seen as personal prizes for military and diplomatic success. The entry “monarchy” (basileia) in the Suda, a Byzantine lexicon, enshrines this tradition: “It is neither descent nor legitimacy that gives monarchies to men, but the ability to command an army and to handle affairs competently.” It is surely no accident that Ptolemy refrained from assuming royal status at least until he had beaten Antigonus back from the gates of Egypt.62 The nearest of them all to a traditional territorial monarch was Cassander, who in at least two inscriptions, as we have seen, is described as “King of the Macedonians.”63 And it was Cassander against whom Antigonus and Demetrius soon concentrated their forces.

First, however, Antigonus was anxious to establish complete control of the sea lanes, and to achieve this end there was one island bastion, still fiercely independent, that he would have to reduce: Rhodes. Officially neutral, the Rhodians had made treaties with all the competing dynasts,64 and by trading undisturbed all round the Mediterranean had become immensely wealthy, putting down pirates—which got them in everyone’s good books—and carefully avoiding commitment in the matter of Alexander’s funeral games.65 However, they did in the end lean toward Ptolemy, since the bulk of their revenues came from trade with Egypt, and since they got most of their food there. But though they had refused to take part in the Cyprus campaign,66 their plea of neutrality cut no ice with Antigonus, who was ready to find any excuse to reduce the island, and to jettison fine talk of freedom and autonomy in the process. This is perhaps not surprising, since earlier he had won valuable concessions from the Rhodians (315–312; see p. 23), including the operation of a shipyard, the use of warships, and some kind of military alliance.67 He nearly scared them into surrender without a fight, but then insisted both on getting a hundred of their noblest citizens as hostages, and on having access to their harbor for his fleet (summer 305). The Rhodians decided to resist, and Antigonus sent Demetrius with a strong force to reduce them.68 Demetrius had nearly four hundred ships, as well as great siege towers—including the famous city stormer (helepolis), over a hundred feet high and with a sixty-foot base69—torsion catapults, rams, fire arrows, and other new mechanical devices. The siege dragged on inconclusively for a year,70 and in the end there was a compromise peace: the Rhodians finally surrendered their hundred hostages, and agreed to ally themselves with Antigonus except in any war against Ptolemy. In return they were left autonomous, ungarrisoned, and (what was for them most important) in possession of their own revenues. This successful defense was the basis for the influence they were to exercise, as a free and independent naval power, for the next century. In gratitude to Ptolemy, who had not only kept them victualed throughout the siege but had also sent them valuable military aid, they established a cult of Ptolemy the Savior (Sōtēr);71 and to commemorate the raising of the siege they commissioned a giant statue of Helios, the so-called Colossus of Rhodes, which stood at the entrance to the harbor and was numbered among the Seven Wonders of the ancient world. This short-lived monument to gigantism (it was shaken down by an earthquake ca. 227 B.C.) stood 105 feet high, took twelve years to complete, and cost three hundred talents, the proceeds from the sale of Demetrius’s siege engines. Few people, we are told, could embrace its thumb. A convenient oracle, doubtless to the Rhodians’ great relief, forbade its reerection, though the disiecta membra long remained a tourist attraction.72 Contrary to general belief, it did not bestride the mouth of the harbor.

One reason Antigonus and Demetrius had raised the siege of Rhodes was to have a free hand in Greece against Cassander, who from his base on Euboea was making constant raids on Athens and the surrounding countryside.73 Demetrius, now tagged with the ambivalent title “the Besieger” (Poliorkētēs), seized the Isthmus of Corinth (304/3), robbed Cassander not only of Corinth, but also of Chalcis in Euboea, won all Arcadia except for Mantinea, wrested Sicyon from Ptolemy’s garrison, conquered Achaea, and installed a Macedonian garrison on Acrocorinth, which remained there over sixty years as a permanent safeguard, until Aratus removed it in 243 (see p. 151). Sparta, however, he prudently left alone.74 Meanwhile Antigonus was busy with administrative problems in Asia Minor. We possess two letters he wrote—qua adviser, but nevertheless clearly expecting compliance—about the proposed merger (synoikismos, “synoecism”) between the communities of Teos and Lebedos in Ionia. The population of Lebedos was to be transferred en bloc to a new common site, and the letters go into endless detail—fiscal, legal, economic— about just what such a move would entail. Even if Antigonus merely endorsed plans drawn up by a corps of secretaries, these interminable recommendations on ground rents and allocation of houses, civil lawsuits and public services by individuals (leitourgiai), the grain-reserve fund and the assessing of taxes, strongly remind us that he—like other Hellenistic rulers—was a good deal more than a mere condottiere, the warlord suggested by our literary sources.75 But this particular synoecism was never in fact carried out. In 302 Teos was conquered for Cassander, and in the following year Antigonus’s death at Ipsus left all his administrative plans void.

By the spring of 302 Demetrius was, after his successes, at last in a position to revive something like the old League of Corinth, which Philip II and Alexander had established and controlled—though whereas Philip’s league had been an alliance of Macedon with the Greeks, what Demetrius envisaged was a Greek alliance against Macedon.76 He saw it as excellent propaganda; besides, to establish, if not a common peace (koinē eirēnē), at least a general alliance (symmachia) through the League not only would facilitate the subsequent control of Greece, but—more immediately important—would serve as a political base from which to launch an all-out attack on Cassander and Macedonia.77 To organize Greece in such a way that it would willingly defend itself against their rivals was a regular policy of the Macedonian kings.78 Idealistic attempts to interpret the League of 302 as the instrument for creating a “United States of Greece” are fundamentally mistaken.

The League duly elected Demetrius the Besieger its captain-general, and he marched north with the intention of finishing off Cassander. Here he and his father missed a great opportunity. Cassander desperately sued for peace, but Antigonus, to whom he applied, held out for unconditional surrender.79 This Cassander understandably balked at; and his refusal left him with only one possible option, a coalition with Antigonus’s other opponents, Ptolemy, Seleucus, and Lysimachus. They welcomed him with open arms.80 The allies had a bold strategy: the defense of Macedonia was abandoned in order to draw both Demetrius and Antigonus together into Asia Minor. Antigonus, now over eighty and vastly corpulent, seeing final success at last within his grasp, took the bait and summoned Demetrius from Europe for a decisive test of strength. While Ptolemy, in a (largely self-serving) diversionary tactic, invaded Syria,81 Lysimachus, Cassander, and Seleucus brought Antigonus and Demetrius to battle at Ipsus, in Phrygia (301).82 Seleucus’s Indian war elephants carried all before them.83 Demetrius, though he led a successful cavalry charge, was so carried away with the excitement of victory that he left the main body, and was never able to get back (partly, again, because of Seleucus’s elephants) to rescue his father, who fell, mortally wounded. Without Demetrius, and with Antigonus dead, the battle was lost.

Demetrius fled to Ephesus. Apart from the powerful fleet that Antigonus had built up with such care, his assets were now limited to Cyprus and a scatter of coastal cities. The allies were left to parcel out Antigonus’s domain among them, “cutting it up like a huge carcass,” as Plutarch says, “and each taking his slice.”84 Lysimachus took most of Asia Minor (thus at last gaining control over both sides of the Hellespont) as far as the Taurus Mountains, except for parts of Lycia, Pamphylia, and Pisidia, which were variously held by Demetrius and Ptolemy. Ptolemy’s Palestinian campaign had netted him the whole of Syria and Phoenicia south from Aradus and Damascus; Seleucus soon arrived, insisting that under the victors’ agreement Coele-Syria should be his, and hinting fairly broadly (when Ptolemy complained that he had been omitted from the share-out) that those who fought at Ipsus should have the sole right to dispose of the spoils.85 For the moment this frontier problem was settled amicably; but Coele-Syria, as we shall see, was destined to become a bone of contention between Ptolemies and Seleucids for centuries. Cassander made no claims in Asia, but expected a free hand in Europe.

The removal of Antigonus One-Eye, it is often said,86 marked the end of an era. Yet the ghost of Alexander’s empire proved singularly hard to lay, and it was to be another twenty years and more before the final bids for supreme power were made and defeated. Only then did the lasting pattern of the Successor kingdoms become clear, and the overriding mood of the Hellenistic age—dynastic autocracy in public affairs, commercial or intellectual disengagement in private life—begin to establish itself throughout the Greek world. At this point it may be advantageous to look back a little, to see how these conflicts affected a single city that had once, but no longer, stood at the center of Aegean affairs: Athens.