The period between Rome’s defeat of the last Macedonian king at Pydna (168) and the sack of Corinth by Mummius (146)—a lurid and notorious climax to the so-called Achaean War (bellum Achaicum)—has been stigmatized by modern historians for its incoherence, confusion, partisan anarchy, and lack of conscious purpose. Until the eleventh hour, we are told, Rome had no positive or consistent policy in Greece, Macedonia, or Asia Minor.1 It was a world, says Edouard Will, “in the final stage of decomposition, only awaiting the coup de grâce and . . . the peace of the graveyard.”2 There is some truth in this; but the pattern is perhaps clearer, and Rome’s long-term policy less shapeless, than such a verdict might suggest. Polybius at one point comments, shrewdly, on Rome’s constant capacity to profit by the mistakes of others;3 and whether or not she here applied her famous dictum of divide-and-rule with deliberate foresight, it remains undoubtedly true that everywhere she found division, and ended by ruling. Her generals and commissioners were confronted, again and again, with “conflicting parties whose one idea of political liberty was to fight each other.”4

Roman political disclaimers of imperial or expansionist ambitions, genuine so far as they represented governmental thinking, were offset, and eventually denied, by the rapacity of her speculators and proconsuls. Senatorial noninterventionism (or inertia)5 had to compete with the intrigues of businessmen, ambitious officials, and their backers, and was to some degree exacerbated by conflicting policies within the Senate itself.6 If there was a consistent or dominant senatorial foreign policy during this period (which is debatable), it was to preserve a balance of power between stable, friendly, or neutral foreign states such as would, with minimal interference on Rome’s part, effectively prevent a recurrence of the Carthaginian nightmare. The cynicism and self-interest that Polybius saw everywhere after Pydna indeed existed, and grew worse as time went on; but how far he was right to identify this mood as the motivating force behind senatorial policy is quite another matter. Our evidence suggests rather a radical split between traditional, that is, aristocratic, senatorial opinion, which was by instinct isolationist and, in the last resort, morally based, and the exploitative plans of the business community, joined very soon by on-the-spot officials, with the latter slowly but surely shifting the former toward more aggressive involvement. This process was hastened by Sulla’s reform of the Senate: a flood of new entrants dependent on non-landed wealth rapidly eroded old principles and sharpened official greed.7 The conflict of the censors with the tax farmers (publicani) in 169 shows, already, a surprisingly strong popular interest in the latter’s contracts, as well as clear senatorial awareness of the dangers inherent in powerful business consortia.8 The closing of the Macedonian mines two years later (above, p. 376), and their reopening in 158, reveals a similar conflict between the public and the private sector: Livy stingingly observes that the mines “were unworkable without a contractor, and the presence of a contractor meant the flouting of common law and the denial of freedom to the allies.”9

Far from trade following the flag (or in this case the fasces), Rome’s military machine and administrative authority—exercised increasingly as time went on by those with a large stake in overseas commercial exploitation themselves—were invoked, again and again, to protect or enhance her own vested interests. Trade went in first, and the flag followed. The Romans, moreover, did not regard warfare as an occupation for gentlemen: they expected to turn a profit on any campaign, and were not fussy about how they did it. The widespread massacre of Roman traders, tax collectors, bankers, and similar oppressive profiteers during Mithridates VI’s “night of the long knives” in 88 (below, p. 561) both highlights the bitter resentment felt by the Greeks, and indicates very clearly what its specific occasion was—not senatorial policy, but uncontrolled (and to a great extent uncontrollable) free enterprise. This dichotomy is apparent, in increasingly acute form, from Pydna onwards, and exercises progressively greater, if often unacknowledged, control over military activity in the East.

Thus from the Third Macedonian War onwards “destruction of cities, enslavement of the population, requisitions, confiscations, were of constant occurrence.”10 Freedom for the Greeks had been all very well so long as they behaved themselves as good clients, eschewed imperial ambitions, and carried out Rome’s wishes. This raises the intangible yet crucial problem of the psychological relationship subsisting between Rome and the Hellenistic states during this final period of the latter’s titular independence. It has often been remarked (indeed, no student can avoid noticing the phenomenon) that interstate diplomacy consisted to a surprising degree of, on the one hand, embassies to Rome (from kings, or leagues, or individual cities), complaining about their rivals and seeking redress through arbitration; and, on the other, of commissions of inquiry sent out by the Roman Republic to settle the problems thus raised. These commissioners saw themselves as vested with absolute authority, subject only to senatorial approval, to settle Greek matters by fiat. At the same time Rome felt no obligation to enforce, by military or other means, the decisions thus reached. That was the responsibility of the interested parties.

It is sometimes surprising just how far this noninterventionism would go. Gnaeus Octavius, sent out east as head of a three-man delegation to check on Seleucid compliance with the terms of the treaty of Apamea, found—in contravention of what had been agreed11—a large fleet and numerous royal war elephants. Without more ado his men set about burning the ships and hamstringing the elephants. An enraged observer of this scene thereupon assassinated Octavius (163/2), and felt so confident in the justifiability of his act that he offered to come to Rome and defend himself before the Senate.12 Lysias, regent for the young Antiochus V (p. 439), gave Octavius a ceremonial funeral and sent a mission to Rome disclaiming responsibility for the murder. The Senate made no comment one way or the other, though on the face of it they had every reason for moral outrage, if not for a declaration of war. From all this it seems clear that Octavius was a hard-liner who had considerably exceeded his official brief:13 similarly, Popillius Laenas’s offhand brusqueness with Antiochus IV (above, p. 431) was undoubtedly his own improvisation, not senatorial policy.

Such violent incidents, however, were rare. For the most part the relationship that now developed between Rome and the Greek kingdoms or cities was essentially parental in nature, with the Greeks playing the part of quarrelsome, feckless, undisciplined children, while Rome functioned as an increasingly stern paterfamilias. A situation of this sort is never altogether imposed by external action; nor is it exclusively one-sided. The game of unhappy families requires at least two players, and this remains as true at the political as at the personal level. If Rome from the beginning saw her role in Greece and Asia Minor as that of an authoritative arbiter (but one pleasantly free of any responsibility for enforcing her judgments),14 the quarrelsome and increasingly fissile Greeks were, likewise, only too glad to find a higher authority to take the burden of ultimate decisions and responsibility off their shoulders. Neither side, perhaps, was ever fully conscious—at least till it was too late, and the course of events had become irreversible—of the part that circumstances had forced it to play.

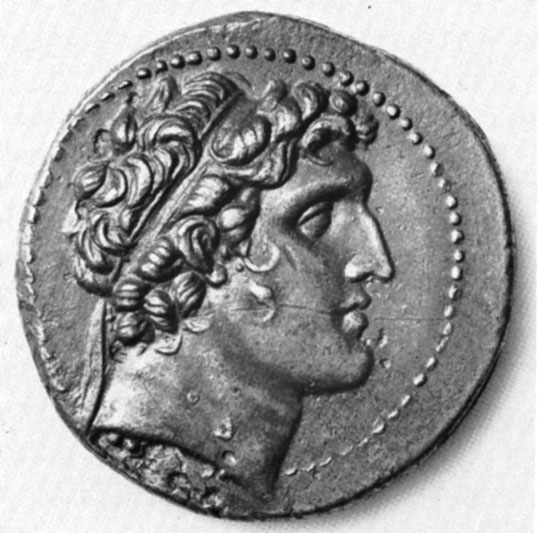

After Pydna, with the elimination of Macedonia and—less often noticed—Illyria,15 the Successor kingdoms were reduced to two. Of these the Seleucid, largely on account of the personality of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, seemed in 167 the stronger and more aggressive. We shall in due course see something of Antiochus in his dealings with the Jews, and understand why the Judaic tradition draws him as a monster of cruelty (pp. 513 ff). To Polybius he was more of an eccentric.16 Like Peter the Great, he was fond of hobnobbing with craftsmen and metalworkers—a sign of mental instability to the class-conscious Polybius. He would stroll through the streets of his capital, alone or with two or three attendants, distributing largesse—gold rings, pebbles, knucklebones—as the fancy took him. He liked louche parties and low drinking companions. Like Nero, he fancied himself as an actor. He frequented the public baths, where on one occasion he emptied a jar of expensive unguent over his fellow bathers, for the fun of seeing them all roll about the slippery floor to get a share of it. Wits in Antioch, as we have seen, changed his royal epithet of Epiphanēs (“Manifest,” of a god) to Epimanēs (“Manic,” “Crazy”).

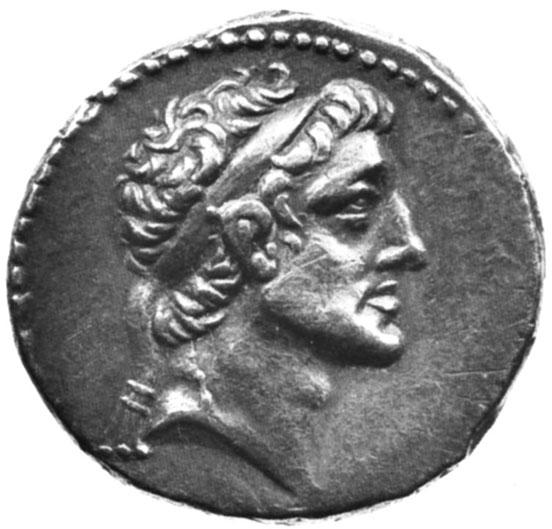

Yet his behavior as king, his official persona, shows a very different side to him. His royal title, and his identification on his coinage as Helios, the Divine Sun, were part of a careful campaign to legitimize his questionable accession. The first five years of his reign he had, technically, been regent for Seleucus IV’s young son, whom he appears to have adopted,17 and then, after the birth of his own son, the future Antiochus V, had put to death (170/69). This usurpatory move coincides with the first emission of the Helios-type coins.18 The symbolism of the sun as first among all heavenly bodies, the all-powerful universal eye of the world, and hence, as Cleanthes said, its leading principle (hēgemonikon), is obvious.19 No accident that Antiochus chose to emphasize his own divinely justified and absolute power at this precise point, or that we find him described in an inscription as “Savior of Asia.”20 Like his father, he worked to reconsolidate the empire’s military strength and extend its frontiers. By the end of his comparatively short reign he was regarded as the most powerful Greek monarch of his time,21 despite his failure to achieve much more than the maintenance of “a precarious status quo.”22

Antiochus’s great forte was political propaganda, as his calculated use of the currency makes clear; he put himself forward as the patron and benefactor of the Greek cities, and a staunch defender (bearing in mind his own divine pretensions) of the traditional Greek gods. He sought dynastic prestige, and was, as even Mørkholm grudgingly admits, “a shrewd politician who may even deserve to be called a statesman.”23 In his dealings with Rome he was shrewd, cautious, and diplomatic: a buffoon or a megalomaniac would never have appreciated the significance of the circle that Popillius Laenas drew round him, much less have pulled out of Egypt as he did. He would have had the Roman’s head off his shoulders, and committed himself to a war he could not hope (and knew he could not hope) to win. Antiochus had been humiliated by the Day of Eleusis. He had counted too much on Rome’s support because of his long residence and personal connections there. He would not make that mistake again. The lesson that Antiochus III had learned, the hard way, at Magnesia-by-Sipylos had not been lost on him.

In this spirit he sent an envoy to Rome bearing the message that peace with the Roman people was preferable to any victory over Egypt. He also congratulated the Romans on their triumph at Pydna. The grateful envoys of the two Ptolemies, their uneasy joint rule one more testimonial to Roman diplomacy, reached Rome about the same time, and were well received. Antiochus returned home, and solaced his pride and reputation with extravagant ceremonial. But like the May Day parade in Moscow, the processions through Daphne (167/6) were also a demonstration of strength, and as such had an immediate end in view.24 The king had assembled no less than fifty thousand men, not to mention a corps of elephants. The inevitable Roman commission appeared to find out what was going on. He wined and dined them all, and reassured them that he was planning neither a fresh attack on Egypt nor an alliance with Eumenes of Pergamon, now out of favor with Rome (p. 429),25 but a new eastern anabasis to complete the work of restoration his father had begun. Since such a campaign would remove Antiochus from Mediterranean circulation for months and possibly years, Rome, having no stake in the eastern Seleucid empire, could scarcely raise any objections to it. The flouting of military restrictions as laid down in the treaty of Apamea (pp. 436–37) was, for the time being, ignored: Rome did not play this restrictive card until after Antiochus IV’s death, and even then, as we have seen, with no great conviction.

From Antiochus’s own viewpoint this new campaign was essential. Antiochus III had made treaties in the East, but done very little more (above, p. 295). Seleucus IV seems to have restricted his diplomacy to the West. The Bactrian king Euthydemus (p. 334) might have acknowledged Antiochus III as his titular overlord; but Euthydemus’s son Demetrius, after the news of Magnesia reached him, seems to have launched a full-scale campaign of conquest and expansion in the great eastern satrapies.26 It was to meet this menace, as well as to pick up loot with which to help pay off Rome’s heavy indemnity, that Antiochus III had made his last, ill-fated expedition. The fact that Demetrius’s descendant Agathocles in turn fell victim, about 170, to a newcomer, Eucratides I, did nothing to resolve the situation as far as the Seleucids were concerned. The Parthians, too, under an equally aggressive new monarch, Mithridates I Arsaces V (acceded 171?), were also threatening the stability of Antiochus’s always insecure territories beyond the Tigris. Another anabasis was urgently needed.

In the midst of Antiochus’s preparations came news of a major Jewish revolt (below, pp. 513 ff.). The king’s tough response to this (167) must be assessed in the context of his forthcoming eastern campaign. Here was a fire that needed quick and effective dousing, since the last thing any eastern campaigner needed (as Alexander the Great well knew) was trouble in his rear. Thus it was not until 165 that Antiochus Epiphanes finally set out, leaving his nine-year-old son and designated heir,27 the future Antiochus V, in the guardianship of his chief minister, Lysias. However, he got no farther than Persia, where he fell ill and died (164), still in his early forties.28 Among his last alleged acts were an edict rescinding the decree of persecution against the Jews, and the dispatch of one Philip, at the head of an army corps, to replace Lysias as chief minister and take over the guardianship of young Antiochus.29 What was the significance of these decisions?

Lysias, in Antiochus’s absence, had suffered a humiliating series of defeats at the hands of the Jewish insurgents, culminating in one for which he was personally responsible. He therefore urged Antiochus to grant amnesty to all Jewish guerillas who returned to their homes. This, perhaps with some misgivings, Antiochus did (early 164). But he refused to deal with Judas Maccabaeus, the leader of the revolt, preferring instead to negotiate through Menelaus the High Priest and the Jewish Hellenizing party (below, p. 518). Thus Judas was faced with the choice of capitulation to Menelaus or fighting on: his decision was never in doubt. Though the Akra, the citadel, held out, Judas captured the rest of Jerusalem, and in December 164 purified the Temple—an act still commemorated by the feast of Hanukkah. Then, in 163, he launched an attack on the Akra itself.

Lysias dispatched a strong force to counter this attack, but when he was on the point of defeating Judas, he instead (as the representative of the boy-king Antiochus V) made peace with him: a peace that had senatorial approval.30 Why did he do so? For one thing, he knew that Philip was coming back to replace him as regent and chief minister, but had no more idea than we do whether this appointment originated (as Philip claimed) with the dead king, or had been invented by Philip himself for his own benefit. Lysias was equally aware that the murder of Seleucus IV in 175 (above, p. 429) had left a rival claimant to the Syrian throne in the person of Seleucus’s son Demetrius, since 176/5 a hostage in Rome.31 Lysias thus needed to get the Jewish question settled fast. In the name of Antiochus V a decree was promulgated admitting the incompatibility of the Mosaic Law and Hellenism, officially returning the Temple to Yahweh, and guaranteeing “ancestral traditions.” Menelaus was executed, but the Akra retained its garrison, and another Hellenizer, Alkimos, became High Priest.32 For the Jewish people, this was the first step toward true independence; for Lysias, it meant the defeat of Philip and the retention of the regency—for a while: in Seleucid politics nothing was ever certain for long.

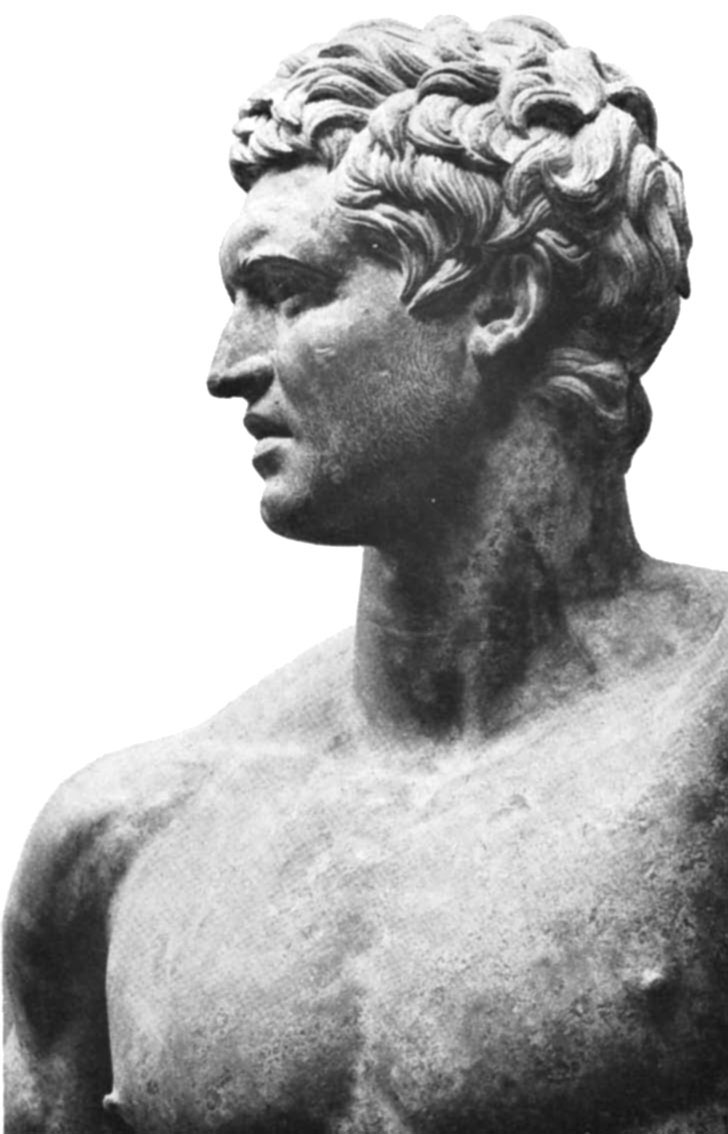

The moment he heard of his uncle Antiochus IV’s death, the young prince Demetrius in Rome went before the Senate with his claim to the throne. He was vigorous, intelligent, dynamic, good-looking, twenty-four years old, and Seleucus IV’s legitimate son: in other words (says Polybius) as far as the Romans were concerned, a disruptive menace.33 Far better a boy-king and a pliable regent: these the Senate knew how to handle. This sounds like mere Polybian disgruntlement. The obvious aim was to avoid further destabilization of the regime. As Polybius himself admits, those at the top in Syria did not want Demetrius’s restoration, and sending him back would have provoked an inevitable civil war.34 Demetrius’s claim was turned down.35 Clearly there existed a split in senatorial opinion over Syrian policy: it was now that a commission betook itself to Antioch and began checking on Seleucid military resources (163/2), with unfortunate results (above, p. 437).

Demetrius, after a second rebuff,36 seeing he would get nowhere through official channels, enlisted the aid of sympathizers in Rome, Polybius among them, and contrived to escape.37 (Polybius is unlikely to have acted without the connivance, if not the active support, of his powerful Scipionic patrons.) In 162/1 Demetrius disembarked at Tripolis in Phoenicia, and made straight for Antioch, where he received an enthusiastic public welcome as the legitimate heir to the throne (which, it could well be argued, he in fact was). Resistance quickly collapsed: Philippus’s men at the top did not, it is clear, have the people behind them. Lysias and young Antiochus V were executed; several other would-be pretenders and supporters of the boy-king were dealt with in very short order. A Roman embassy under Tiberius Gracchus was sent out to observe and report. Demetrius duly flattered Tiberius, showed himself eager to collaborate, and was well reported on. He even sent Octavius’s murderer to Rome, along with the usual honorific gold crown. The Senate accepted the crown, and released the murderer, who thus found his cheerful confidence well justified.38 The motive, as Polybius saw it, was to hold charges in reserve against a more profitable occasion. Demetrius was recognized as king—conditional on his satisfactory conduct.39 The Senate showed itself cool and cautious, but by no means overtly hostile.

It is true that in 161 Rome, on Judas Maccabaeus’s initiative, made a treaty with Judaea:40 since this was a mutual defense pact, it in effect recognized Judaea as an independent state, and one Jewish source alleges that the Senate wrote to Demetrius, threatening him with war if he continued his harassment of the Jews.41 Is this letter mere fictional propaganda? Hard to decide, and in any case it does not matter, since Demetrius failed to take the slightest notice of it. He went ahead and crushed the rebellion regardless. Judas Maccabaeus died without either demanding or getting help from Rome, and the Senate took no retributive action. In the circumstances we may legitimately wonder just what this much discussed treaty was really worth. Once again Rome had obliged with the intangible seal of her auctoritas, but then refrained from action. “From the senate’s vantage point, the Jews . . . could claim independent status. But the maintenance of their independence was not Rome’s affair.”42

In Egypt, the reconciliation of Ptolemy VI Philometor and his younger brother, Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II Physcon (above, p. 430), was proving predictably fragile.43 Philometor’s sister-wife, Cleopatra II, reigned as the third member of this odd triad. Alexandria seethed with palace intrigues: the mob was restless, the troops were mutinous, while the fellahin plotted insurrection, aided and encouraged by the native Egyptian priesthood.44 When Popillius Laenas forced Antiochus Epiphanes to hold his hand at the very gates of Alexandria he must have wondered, in his heart of hearts, if Rome was not perhaps backing the wrong horse. But orders were orders: he hopefully urged the three co-regents to maintain brotherly (or sisterly) concord, and then removed himself before they could disregard his official advice. Like most compromises, this one made for trouble. Someone should have recalled Odysseus’s shrewd saying: “Multiple rule is no good: let there be one king, one ruler.”45 The obvious candidate, for ability as well as on grounds of precedence, was Philometor. But lacking absolute authority and adequate backing, what could he do? He showed himself a clever, civilized,46 and (for a Ptolemy) energetic ruler; but he could not fight everyone at once. In October 164 the machinations of his brother drove him from Alexandria to Rome, where he quietly took up residence in a working-class district, in ostentatious poverty, and waited for the authorities to discover his plight and come to him, in embarrassment and with largesse, which duly happened.47

However, as regards substantial political aid, Philometor’s venture got him very little. He had not yet learned the simple lesson that in their dealings with foreign rulers the Romans much preferred winners to distressed suppliants. The Senate opted for the status quo, merely instructing a mission already on its way to Asia Minor to visit Alexandria and effect a reconciliation.48 Philometor thereupon took off for Cyprus, to have some sort of base from which to operate.49 Envoys from Alexandria, where Physcon’s rule was proving intolerable, soon arrived begging Philometor to come back. This change of heart in Alexandria may well have dictated what happened next. In May 163 the two brothers, with the approval of Rome’s commissioners, agreed on a partition of the realm: Physcon would rule the western province of Cyrenaica, while Philometor was to reign in Egypt.50 It was a makeshift solution, and one that—since Philometor did so well out of it, reducing Physcon to his more proper status of crown prince—in no way reduced, indeed exacerbated, the brothers’ rivalry; but at least it gave the country a breathing space, and it held up, precariously, until Philometor’s death in 145.

Even so, both brothers continued their opéra bouffe attacks on one another. Physcon, complaining that partition had been forced on him against his will (which was true enough), talked the Senate into backing his claim on Cyprus. Philometor ignored this ruling, and Physcon failed to reconquer the island.51 As a result the Senate repudiated its alliance with Philometor, and sent his ambassadors home (161), a clear notice to Physcon that he had considerable latitude of action.52 Perhaps in consequence of this Philometor tried, unsuccessfully, to have Physcon assassinated (156/5).53 At this Physcon, still planning the recapture of Cyprus, announced that if he died childless he was bequeathing Cyrenaica to Rome.54 (We have an inscription recording the will: no ancient literary source, interestingly, refers to it).55 He then went back to Rome, showed (like Peisistratus) the scars of his attempted assassination, and finally got some token military support—five ships, Roman advisers, and the authorization to levy Greek troops at his own expense—for his Cyprus venture.56 Why a majority in the Senate supported him is uncertain; Cato, for one, was against the idea, and spoke in favor of Philometor,57 being old-fashioned enough to find Physcon not only politically opportunistic but morally offensive. It is tempting, though perhaps overspeculative, to see this vote as an index of the profound change in ethical values now taking place at Rome.

In any case the Cyprus expedition fizzled out ignominiously, and Physcon was captured by his brother. Philometor, with commendable patience (and perhaps a little uneasy about the line Rome might take over that provisional bequest of his vital western frontier province), not only spared Physcon’s life, but offered him his own daughter Cleopatra Thea, Physcon’s niece, in marriage.58 For a family in which sibling incest had became almost de rigueur, this merely nepotic match was very small beer. Obviously Philometor was hoping that Physcon would sire a child in short order and nullify his bequest. He also, on Rome’s insistence, sent his peccant brother back to Cyrene: the distributive status quo was to be preserved. He then appointed his own son, Ptolemy Eupator, governor of Cyprus, with royal prerogatives (Eupator died there, still very young, in 150).59 From now (154) on Philometor’s position was secure, his reputation at its height, his royal cult widespread. The Athenians, to whom he had presented a library and, possibly, a gymnasium, in gratitude erected a bronze equestrian statue of him on the Acropolis (ca. 150), and celebrated the so-called Ptolemaea with great lavishness.60 Benefactions of this kind were common, and formed an integral part of Philometor’s foreign policy, creating not only good will but also, he hoped, a network of accepted obligations. Thus, until Philometor’s death on campaign in Coele-Syria (145), Physcon was stalemated. It is too often assumed that this represented a setback for Roman policy in Egypt. In fact Rome endorsed, indeed insisted on, partition, and had everything to gain from the relatively stable decade that followed as a result, with Physcon well out of the way. To call Rome’s dealings with Alexandria at this time “irrational” or “somewhat erratic,”61 and then to argue that Philometor’s activities subverted such preferred lunacies, is to stand logic doubly on its head. Like Eliot’s women of Canterbury, the Senate did not want anything to happen; and in Ptolemaic Egypt, for a surprisingly long time, what they wanted was exactly what they got.

Demetrius I, meanwhile, was making powerful enemies in Syria. Despite his taste for hunting (which was how he came to meet Polybius) he had a sour, aloof manner: a solitary drinker and possible alcoholic,62 he offered a striking contrast to the eccentric but extrovert Antiochus Epiphanes. He backed the wrong (supposititious) brother in a Cappadocian dynastic feud, and by so doing contrived to offend not only both Rome and Pergamon, but also his own unsuccessful candidate, Orophernes, who—accusing Demetrius of lukewarm support—raised the Antioch mob against him.63 The rising was put down with violence: this did not make Demetrius any the more popular.64 To add to his troubles, Attalus II of Pergamon—who had at last, aged over sixty, succeeded to the throne on the death of his brother Eumenes II (160/59), was on much better terms with Rome than Demetrius,65 and in due course established himself as the leading dynast of Anatolia66—now produced a pretender to the Seleucid throne, a character called Balas,67 who claimed to be the son of Antiochus IV (and is so presented by our Jewish sources), but was almost certainly an impostor.68 Impostor or not, Attalus packed him off to Rome, where the Senate—still prevalently hostile to Demetrius, and now sensing his weakness—approved Balas’s dubious credentials (153/2). To do so, as usual, committed them to nothing. Polybius’s predictably tendentious account of the debate denigrates both the motives and the intelligence of those supporting Balas,69 claiming that “balanced” senators saw through him.70 In point of fact Balas probably seemed, at this juncture, the lesser of two evils, with a better chance of stabilizing the regime.71

Endorsement, of course, did not imply material aid. Rome, it should be remembered, was at war in Spain, and already contemplating a third round against Carthage: there were more pressing problems to settle than the endless squabbles of petty Hellenistic dynasts. Balas might have Rome’s approval, but his real backing came from Attalus, Ptolemy VI (his eyes once more turned toward Coele-Syria), and Ariarathes V, the successful claimant in Cappadocia.72 Now styling himself Alexander Balas, he landed at Ptolemaïs-Ake, near Mt. Carmel. Both he and Demetrius began bidding vigorously for the support of the Jewish guerilla commander Jonathan (152/1; cf. below, p. 523); Demetrius offered him, inter alia, the military command in Judaea, with the right to levy troops, while Balas countered with the post of High Priest.73 Jonathan accepted both offers, but took Balas’s side (Oct. 152). After a short campaign Demetrius died fighting (winter 151/0), and Balas, the impostor, became king.74

Ptolemy VI, shrewd and patient, saw at once that here was a simple adventurer, who relished the trappings and perquisites of power, but was otherwise lacking in both dynastic ambition and political savoir-faire. He therefore encouraged Balas (150/49) to marry his daughter Cleopatra Thea, briefly betrothed earlier to Physcon, who had other ideas in mind.75 This time the wedding came off, and “one of the most energetic and murderous” Hellenistic queens,76 strong-featured child of incest and ambition,77 was duly launched on her lurid career. But all this lay in the future: for the moment the bride’s father had his own reasons for the match. No Ptolemy would ever pass up the chance of becoming the power behind the Seleucid throne: certainly not while Coele-Syria was still potentially recoverable.

Ptolemy’s chance soon came. Though Demetrius I had been killed, his sons had escaped, and now young Demetrius II returned to Syria with a force of Cretan mercenaries. Ptolemy, as though going to his son-in-law’s assistance, swept north into Palestine. Jonathan of Judaea, similarly on the lookout for gain, now occupied the ports of Joppa and Ascalon. Balas, who at least had the wit to see what Ptolemy was about, tried to procure his assassination. The attempt failed. Ptolemy pressed on north toward Antioch. His daughter Cleopatra Thea found her way back to him (having had the good sense to realize that Balas was finished), and Ptolemy, declaring her marriage void, coolly prepared to refurbish her as a bride for the young Demetrius: the price, it goes without saying, was Coele-Syria.78 The volatile citizens of Antioch, having transferred their allegiance from Balas to Demetrius, now took even the intrigue-hardened Ptolemy by surprise: they acclaimed him as the new Seleucid monarch. Ptolemy—like his ancestor Soter in very similar circumstances (above, p. 14)—must have had a moment of quite appalling temptation.79 The ultimate prize that had so bedazzled Ptolemy III had been tossed into his lap. But the prize had come too late, and Ptolemy knew it. This was 145: Carthage and Corinth had both fallen to Rome, and Philometor had not forgotten how Popillius Laenas treated Antiochus on the Day of Eleusis.80 It has been argued that he was confident of being able to count on Rome’s indifference.81 This is the optimism of hindsight. Be that as it may, Philometor refused the offer, and persuaded the citizens of Antioch to stick with Demetrius—who promptly became his new son-in-law, and ascended the throne as Demetrius II Nicator Theos Philadelphos. Loss of Seleucid prestige and territory was compensated for, as time went on, by ever-more grandiloquent and lengthy titles. Balas was killed soon afterwards in northern Syria—by an Arab chieftain with whom he had sought refuge after suffering a crushing military defeat—and his head brought to Ptolemy. Unfortunately, Ptolemy himself was wounded in the same battle, and died two days later. The way was open for his still-resentful brother, Physcon, chafing in Cyrenaica, to stage a comeback—which in due course, as we shall see, he did.82

At this point we must backtrack a few years to follow events in Macedonia and the Aegean world. The frontier bickering between Pergamon and Bithynia (156–154) is of real interest only insofar as it involves more important protagonists:83 for example, when Rome, still smarting at the part Pergamon had played at the time of Pydna, in 166 proclaimed the freedom of the Galatians, and publicly snubbed Eumenes II by passing a decree that placed Rome off limits for any king.84 The partial eclipse of Rhodes by Delos had led directly to a recrudescence of piracy, since it had been the Rhodian squadrons that patrolled the sea lanes.85 Once again Roman policy had been ad hoc and shortsighted: a century later it would take the Republic’s full resources, under Pompey’s direction, to clear the Mediterranean of this scourge (below, p. 657). Economic distress still further exacerbated the tensions between haves and have-nots; yet the crop of pretenders recorded during this period makes it all too clear that monarchy was still seen as the only feasible solution in political terms.

The most notable of these pretenders appeared in Macedonia.86 His name was Andriscus, but he claimed in fact to be Philip, Perseus’s son by Laodice (who of course was not only Seleucus IV’s daughter, but also Demetrius I’s sister).87 Demetrius, who, as we have seen, had problems of his own, sent Andriscus to Rome (153/2). The Senate was not interested. Not, that is, until Andriscus—after conning travel funds, slaves, royal robes, and a diadem out of an ex-concubine of Perseus, royal recognition from Byzantium, and troops from various Thracian chieftains88—advanced from Thrace into Macedonia (like a bolt from the blue, Polybius says),89 and won control of the country after two battles (149/8). Opposition came chiefly from the landed classes, as we might expect: Andriscus proscribed men of wealth and property, basing himself on popular support. This proved both widespread and enthusiastic: so much so that Andriscus extended his operations into Thessaly. It seems clear that Macedonians would rather have a king, any king, than be parceled out into faceless cantons and lose their much-treasured ethnic identity.90 A hastily mustered Roman force was cut to pieces by the pretender; but two more legions, under Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus, soon put an end to Andriscus’s career—with symbolic aptness, at Pydna (148).91 Macedonia now lost its independence entirely, becoming, with Illyria, a Roman province. One of the first marks of permanent Roman occupation was the construction of that great trunk road the Via Egnatia, which ran from Epidamnus on the Adriatic to Thessalonike, where the governor now had his headquarters.92 Its well-engineered linkage of the northern Balkans was a visible condemnation of separatism, and ushered in an era of pragmatic unification such as even Alexander had never dreamed of.

The gold and silver mines had already been reopened, in 158 (above, p. 436); Polybius, no Macedonian irredentist, remarks that Rome had proved Macedonia’s benefactor by freeing her both from a tyrannical monarchy and from her internal dissensions.93 Yet—perversely, viewed in Polybian terms—there were many, still, in the Greek states as well as in Macedonia, who preferred the freedom to pursue their own feuds and intrigues over the well-ordered tutelage of Rome. Andriscus was not the only leader who could count on the support of the dispossessed or politically alienated masses. Roman brutality and highhandedness after Aemilius Paullus’s conquest in 168 had not been forgotten; nor had the collaborationist activities of pro-Roman oligarchs such as Callicrates (above, p. 425). The Achaean League had fought as Rome’s ally in turn against Philip V, Antiochus III, and Perseus. It is a mark of how far public feeling had changed in a short time that by 146 the League’s leaders were ready to engage in a desperate last-ditch war against Rome, which they must surely have known, in their innermost hearts, that they had no real chance of winning. Why was this? A class struggle has been suggested, with the Greek masses, whipped into action by Achaean demagogues, rising against Rome as the power behind their oppressive oligarchical regime.94 Yet while it is true that Rome, notoriously, tended to back the wealthy upper classes in any country, she was also ready to accept, in a true pragmatic spirit, support from wherever it might be offered,95 and this by no means always meant the propertied classes. Per contra, it was by no means only the dispossessed who nursed fierce dreams of independence.

Alternatively, the initiative has been attributed to Rome, anxious for an end to her complex and ultimately unsatisfactory policy of nonintervention in Greece, and thus implementing an administrative mopping-up operation to round off the provincialization of Macedonia.96 Yet this too seems unlikely. For one thing, the Senate was preoccupied, to the exclusion of almost everything else, with tough campaigns against Carthage and the Spanish tribes. A simpler explanation suggests itself. Granted the conditions prevailing in Greece from 167 onwards, it was only a matter of time before the sullen and resentful subservience, the child—parent relationship symbolized by endless embassies and requests for Roman arbitration, the fear of random Roman cruelty and even more random favoritism, exploded in open, violent, hopeless, and hysterical revolt. Those who characterize the war as a patriotic and nationalistic uprising97—seldom the most rational of enterprises—seem to me to be on the right track.

Already the conflict between pro- and anti-Roman elements had led to a grisly series of reprisals, exiles, suicides, and condemnations,98 sometimes involving torture or other atrocities.99 Polybius was caught between his admiration for Rome and his innate Achaean patriotism. Once the war was lost, he personally argued the Achaean cause in an endeavor to mitigate Roman severity,100 but his real anger, as countless passages demonstrate,101 was reserved for the violent demagogues who led the Achaean League, hopelessly unprepared, into a war with Rome, which they stood no chance of winning.102 The misfortune (atychia) that afflicted the Greeks at this time was, in Polybius’s view, culpable. He even attributes Rome’s success to Providence, to Tyche reversing the effects of atychia: “If we had not collapsed so quickly,” he quotes people as saying, “we should have been utterly destroyed.”103 Not, be it noted, by the Romans (who in this context are made to look like saviors), but by the purges of their fellow citizens, the indiscriminate use of terrorism, which the Achaean populists in office were (or so Polybius claims) making a commonplace instrument of policy.104 There speaks the collaborating liaison officer, Rome’s agent of conformism, and his role explains why Polybius’s villainous demagogues remain, in the end, mere sadistic bogeymen, devoid of rational motivation. He even at one point describes the whole country as “bewitched.”105 He attacks the arrogant, couldn’t-care-less attitude of the freed slaves.106 All this class-conscious social sniping distracts attention from the real, and obvious, driving force behind Achaea’s ultimate defiance of Rome: patriotic nationalism, the will, against all odds, to fight for true freedom and independence. In his ambivalent position Polybius can only argue that to resist the inevitable is criminal stupidity,107 a proposition that—fortunately for mankind—has seldom made much of an impression on committed freedom-fighters.”108

During the decade prior to the Achaean War the differences between various Greek states—Athens and Oropus over violence and illegality in the collection of tolls;109 Rhodes against Crete regarding Cretan piracy (155/4);110 above all, Sparta’s split from the Achaean League over a territorial claim disputed with Megalopolis111—had continued to force themselves on the Senate’s attention, though the Romans still avoided direct intervention where possible, preferring to work through advisory commissions or neutral arbitration. (Since all these cases were rife with bribery and political intrigue, it is hard to blame them.) For example, when the Athenians took their case to Rome, the matter was turned over to Sicyon. Condemned by Sicyonian assessors to pay Oropus damages of five hundred talents, an exorbitant sum, the Athenians played on their city’s intellectual prestige by sending their three leading philosophers (Carneades, head of the New Academy, Diogenes the Stoic, and Critolaus the Peripatetic) back to Rome to plead their cause (155).112 The Romans, who admired Athenian culture but respected legal decisions, let the judgment stand; they did, however, cut the damages assessed by four-fifths. An Athenian garrison was placed in Oropus, and hostages taken.113 Oropus subsequently appealed to the League (not, be it noted, to Rome) against alleged outrages by this garrison and their appeal was upheld—exactly as we might expect, since the Senate ruled that all cases except those of a capital nature should remain under the Achaean League’s jurisdiction,114 and the League had no great love for Athens.

This happened in a further development of Sparta’s quarrel with the League over Megalopolis. The Spartan envoy to Rome challenged Achaean authority; Callicrates the Achaean as firmly defended it; Rome endorsed Callicrates and the League. The endorsement encouraged a highhanded attitude to Sparta on the part of the Achaean government, and the following year both sides once more had embassies in Rome (149/8). Callicrates, the original leader of the Achaean delegation, had died en route,115 which meant that his role as spokesman went to the ranking member, Diaeus, a tough activist in the Philopoemen tradition. Diaeus was not only anti-Spartan, but shrewd enough to exploit Rome’s reluctance to become embroiled in Greek domestic quarrels. A shouting match before the Senate between him and his Spartan opponent produced the promise of yet another on-the-spot Roman commission of inquiry to adjudicate rival claims. For whatever reason, it was a year and a half before it set out, during which time a great deal happened.

We need not (as has often been done) invoke reasons of Machtpolitik for this delay.116 Ingrained and habitual senatorial procrastination seems a far likelier reason. It is also true that, with the pretender Andriscus still operating in Macedonia and Thessaly (149/8), the Roman authorities had more pressing business on hand. They were certainly not bothered at this stage by the League, which provided auxiliaries to help put down Andriscus. Polybius, recently returned from Italy to Achaea (150; see p. 278), was sent, at the consul’s request, to conduct negotiations with Carthage.117 “As late as the spring of 147 there is no sign of anti-Roman activity and no indication of an approaching conflict.”118 Diaeus, meanwhile, had reported that Rome opposed Spartan secession from the Achaean League; the Spartan envoys announced the opposite.119 The Roman commission waited, in tactful indolence, perhaps until Andriscus was defeated, but more probably without a firm policy of any sort except to spin things out as long as possible, before finally landing in Greece (late spring 147). Then, however, their decisiveness made up for lost time. They announced not only that Sparta was indeed to be detached from the League, but that various other cities, including Corinth and Argos, were similarly to be “freed” and enjoy independence.

Here was a surprise, and no mistake. Polybius claims120—and he may well have been in a position to know—that the idea was simply to shock the League out of its stubborn intransigence by scare tactics.121 Perhaps the threat was not meant seriously (there had been numerous precedents for such intimidatory bluster), but this time it was seen, understandably, as a blatant attempt to manipulate the League’s internal affairs, and produced an explosion of resentful fury. The Achaeans had Sparta’s delegates arrested (some of them actually in the houses occupied by the Roman commissioners), and the Romans themselves were roughly treated in the assembly. They returned to Rome at once.122 Yet the Senate, far from taking a tough line, merely sent out a second mission to deliver a mild censure and with a request that the Achaeans themselves should discipline those responsible for the outbreak.123 The League had already sent off its own official mission, led by Polybius’s brother Thearidas, to apologize. The two parties met in mid-journey and got on very amicably. Achaea was simply admonished to avoid further attacks on Rome or Sparta. Though the measure was not officially rescinded, there was no more talk at this stage of forcibly removing cities from the League.124

Diaeus, Critolaus (the stratēgos for 147/6), and their backers may have interpreted this as a sign of weakness.125 Critolaus is, inevitably, pictured as a rabid warmonger by our ancient sources, presumably on a post hoc, propter hoc basis: the Achaean War was, after all, fought and lost during his generalship.126 Yet it was Critolaus who now (autumn 147), at a meeting with Spartan and Roman delegates in Tegea, stalled action for another six months by claiming that only the Achaeans in full assembly could negotiate a settlement, and that their next official meeting (synodos) would not take place until the spring of 146.127 This undoubtedly irritated Sextus Julius Caesar, the Roman commissioner, who returned to Rome fuming about Critolaus’s procrastinating tactics; but was it the insult that made war inevitable?128 Hardly, and certainly not with Thearidas and his conciliatory mission still en route for Rome. What is more, the Romans took no action till, precisely, the following spring—which makes it look as though they had acquiesced in the six-month postponement129—and, even then, when Caecilius Metellus sent yet another legation, it was as amicable as its predecessors.130 It has been suggested that one reason for delay at the Roman end was that there was no qualified magistrate available in 147 to conduct the Achaean War;131 but there is no substantial reason for believing that at this point Rome wanted a war at all. Even Harris, who never misses an opportunity to stress Rome’s supposed aggressiveness and acquisitiveness, has to admit that “the League could cause the Roman Senate no more anxiety than a wasp on a warm afternoon.”132

The situation in Achaea, however, had changed over the winter of 147/6. War fever had indeed swept the country, and Critolaus seems to have been largely responsible for it; but it was directed against Sparta rather than Rome, and the violent anti-Roman propaganda in our sources (which we need not doubt, once war with Rome was a fact) has been antedated by several months from the high summer of 146. It was then that Critolaus inveighed against Roman highhandedness,133 then that Greeks were called to fight for freedom once more, to throw off the strangling yoke of Rome.134 In any case the legation sent by Metellus from Macedonia found the Achaean assembly in a fine lather of nationalistic hysteria.135 Their conciliatory words were shouted down, and they were hustled out of the meeting. With inflammatory talk of traitors and collaborators Critolaus persuaded the assembly to vote for war against Sparta136 and to suspend debt payments for the duration of the conflict, a much-misunderstood measure.137 He also declared his desire to remain on friendly terms with Rome, though not with despots, an ambiguous caveat. What he seems to be implying is that this was a private conflict between Greeks, and interference by outsiders was not welcome. Also, Rome—whether through indifference, or because she was preoccupied elsewhere—had let Achaea have a free hand with Sparta in the past; why should she not continue to do so now?138

But for once Critolaus had miscalculated, and badly. Rome’s patience was at long last exhausted. Achaea’s bellicose determination to settle the Spartan problem by force could not be ignored: the balance of power, as with Antiochus IV in Egypt, was being gravely threatened. When Critolaus marched north to discipline the apostate city of Heracleia he found himself, to his horror, confronted by a Roman army under the redoubtable Metellus (April 146). At Scarphaea, near Thermopylae, he was crushingly defeated, and may have committed suicide.139 Reality had eclipsed rhetoric: the bellum Achaicum was now a fact. A kind of passionate last-ditch determination swept the country. Boeotia and Euboea, Phocis and Ozolian Locris joined the League’s forces.140 The mood resembled that of the American Old South in 1860, and the military preparations were no less inadequate. Nor, clearly, had a vigorous Roman offensive been foreseen. Through the fiery rhetoric we glimpse disorder, civilian panic, flight. Yet once committed, the cities of the League reveal an unshakeable determination to fight on, whatever the cost. A few prominent citizens, predictably, argued for capitulation: they were imprisoned or executed.141 The vast majority of the population—not merely, as has been thought,142 the lower classes— meant to see this crisis through to the bitter end.143

Diaeus manumitted, and enlisted, twelve thousand carefully chosen slaves,144 called for the release of imprisoned debtors, levied a special war fund, and prepared to base his defense on Corinth.145 Metellus’s forces met those of Lucius Mummius, his consular successor for 146. Polybius paints a scene of panic and confusion sweeping the cities of Greece.146 Diaeus refused to negotiate, and was defeated. Mummius settled down to besiege Corinth. Despite his fierce rhetoric, despite the fact that he had executed at least two subordinates who urged surrender on terms, Diaeus, instead of holding out, fled by night with the tattered remnants of the Achaean army, presumably judging his position hopeless (which indeed it had been from the beginning). He made for Megalopolis, where—like the Gaul commemorated by Attalus I’s Pergamene sculptors (above, p. 340)—he first slew his wife to prevent her falling into Roman hands, then committed suicide.147 The Achaean War was over, almost before it had begun. Mummius gave his troops carte blanche to loot and destroy Corinth: in this he was acting on specific senatorial instructions, though probably not (as was once thought) with the intention of eliminating a bothersome commercial rival. Women and children were sold into slavery; any men still in the city when it fell were slaughtered without mercy. This did not stop cities like Elis from honoring Mummius with lickspittle dedications praising his benevolence (sic) toward the Greeks.148 Sparta, the accidental casus belli, never again played any active role in the affairs of Greece.

Corinth was still a heap of ruins when Cicero visited the site, at some point between 79 and 77;149 it was not rebuilt till 44, and then only at Caesar’s express command.150 Polybius, returning to Greece from Carthage, describes the systematic plundering of works of art.151 However unwillingly, the Senate had been led, step by step, after the annihilation of the Antigonid regime, into the dangerous but temptingly profitable labyrinth of a long-term Greek involvement. Like Alexander at Thebes, Rome had finally made clear to the Greeks, in a way that no rhetoric or diplomacy could conceal, just where the true power lay. The slogan of “freedom for the Greeks” had been buried at last in the smoking ruins of Corinth, and it was not to be truly revived until, almost two millennia later, on 25 March 1821, Bishop Germanos raised the banner of revolt against the Turks at the monastery of Aghia Lavra, below Kalávryta152—with symbolic aptness (though probably no one noticed this at the time) in the very heart of Achaean League territory.