For reasons that have little to do with Hellenistic history, the part played by the Jews under Ptolemaic and Seleucid rule tends to get a closer, more detailed scrutiny than, say, the precisely comparable activities of the separatist movements in Bithynia or Commagene.1 What marks off Judaism both in its own right and as the precursor, and seedbed, of Christianity is its ideological element (taking “ideological” as a religious no less than a political term). The fact of faith, as a datum, conflicts with normal historical criticism, presupposes what Eliot called “the intersection of the timeless with time.” The historian, who is required to study the secular genesis of events rather than their divine revelation, cannot in any open sense work sub specie aeternitatis: though he must, and does, recognize the force of faith as a major historical determinant, he can only evaluate it in linear, temporal terms. If he accepts its presuppositions, he becomes, strictly speaking, a propagandist—which means that, for the highest of nonhistorical motives, he has betrayed his calling.

His perspective on events will also be drastically altered. For the clarification of Hellenistic history it should always be borne in mind that the Jewish problem, including the nationalist revolt under Judas Maccabaeus (below, pp. 518 ff.), was, from the viewpoint of Alexandria and, subsequently, Antioch, a comparatively minor affair, involving local tribal politics, and significant chiefly because of its strategic setting, between Idumaea and Samaria, on the marches of Coele-Syria.2 It was also—as should by now be abundantly clear—a phenomenon by no means without precedent. Ethnic revolts within the Seleucid empire were nothing new. Nor, indeed, was the eager embracement of Greek public mores (the use of the gymnasium in particular) by an ambitious elite, coupled with an indigenous indifference to, or active rejection of, Greek religious beliefs and practices (cf. above, pp. 320 ff.). Jerusalem’s Hellenizing upper-class minority can be matched throughout the oikoumenē, from Pontus to Bactria. The emergent Jewish state differed little, in broad political outline, from those of Parthia or Armenia. Even the monotheistic religious ideology underpinning Judas Maccabaeus’s resistance movement had a more or less exact precedent in the priestly opposition to Alexander the Great maintained by the Persian Magi, in the name of the One God Ahura Mazda.3

From the historical viewpoint, indeed, the relationship between Judaea and the great Hellenistic kingdoms offers, first and foremost, a model confirming those stress patterns we have noted in all areas where Seleucids or Ptolemies established their rule over a civilized indigenous population. For the Graeco-Macedonian conquerors there was nothing special, to begin with, about the Jews: they saw Jerusalem as one more polis, and Judaea as the area it controlled.4 Alexander spent little time on Palestine, having other goals in mind, and late accounts (in particular that of Josephus), claiming that he made a special journey to Jerusalem, indeed offered sacrifice there, are mere ex post facto legends, put out by pious ideologues determined to show that the legendary world conqueror knew a true Holy City when he saw one.5 To the Successors, Judaea—indeed, Palestine as a whole, of which Judaea formed the southern part—figured chiefly as territory adjacent to that ill-defined no-man’s-land Coele-Syria,6 fought over by successive Ptolemies and Seleucids in recurrent Syrian wars.

In the fourth century, it will be recalled (above, pp. 28 ff.), Syria and Palestine changed hands several times.7 After Alexander’s death Laomedon held the area till 320, when Ptolemy Soter annexed it.8 In 315 Antigonus One-Eye stormed Joppa (Jaffa) and Gaza and occupied all Palestine;9 Ptolemy in 312 wrested the area from Antigonus’s son Demetrius;10 in 311 Antigonus recaptured it.11 Since Palestine was crucial territory in his conflict with Ptolemy he now almost certainly followed his normal practice of establishing Greek and Macedonian settlers there.12 Thus Greek influence will have made itself felt early. After Ipsus (301) Seleucus, though never officially renouncing his claim,13 in effect conceded control of Palestine to Ptolemy (above, p. 35);14 even so, Demetrius for about another decade still retained control of the great ports of Tyre and Sidon.15

One inevitable result of this protracted tug of war was the emergence of pro-Ptolemaic and pro-Seleucid groups within Judaea itself.16 Ptolemy I seems to have been more popular than Antigonus One-Eye, who had a well-deserved reputation for toughness: thus when Ptolemy pulled out in 311, some of his more committed Jewish supporters, including Hezekiah the High Priest, went with him rather than face Antigonus’s wrath.17 However, Ptolemy’s civility was strictly relative. In 302/1 his return found him in an anything but mild mood. In collusion with his Jewish friends he entered Jerusalem during the Sabbath, and took advantage of the law prohibiting work or the bearing of arms, even for self-defense, on that day—as others were to do later, in the early stages of the Hasmonean revolt (below, p. 517)—to bring the city completely under his control.18 He deported various opponents to Egypt, and when forced to evacuate the city, destroyed the walls so that Antigonus could not use it as a stronghold. But Antigonus’s death at Ipsus brought Ptolemy back to Jerusalem for the fourth time (late 301): he and his heirs held Judaea during the next century, until Antiochus III’s crushing victory at Panion (200: above, p. 304).19

The political status of the Jewish people during this period is of interest. The classic evolution from kings to an aristocratic priesthood had already taken place.20 Also, significantly, the local political representation (prostasia) with the ruling power—now the Ptolemies, as previously the Persian Achaemenids—was no longer vested in a satrap or the equivalent, but exercised by the High Priest, whose office was hereditary and (in theory at least) held for life. Thus what had been a purely cultural autonomy under the Persians was acquiring political characteristics and the potential for independence, and “the High Priest at the head of the people assumed the aspect of a petty monarch.”21 This sacerdotal authority, backed by a council of elders (gerousia) and centered on the Temple, must be clearly distinguished from that operating among the Jews of the Diaspora, for example in Babylonia or Alexandria, where a less rigid, and certainly less politicized, authority prevailed, associated with the synagogue, scribal exegesis, and the reading and exposition of the Torah.22

These dispersed communities were peculiarly exposed to Hellenistic influences; and since their members made pilgrimages when they could to Jerusalem (which was, in any case, by no means cut off from the outside world, especially the world of commerce), such influences, though resisted by strict upholders of the Mosaic Law, nevertheless infiltrated Jewish society at all levels. The Jews of Alexandria, though they lived in a separate community, mixed freely—at least until the late Ptolemaic period, when growing hostilities drove them to embrace the life of the ghetto23— with the Greek population: so much so, in fact, that most of them seem to have lost the use of Aramaic and Hebrew, a major factor governing the production of the Septuagint during the reign of Ptolemy Philadelphos (above, p. 317). The language of the Septuagint closely resembles that of the Graeco-Egyptian papyri, while its vocabulary has parallels in certain Alexandrian writers:24 inter alia it hints, in its use of the terms theos and kyrios to convey Yahweh’s synonyms, Elohim or Adonai, at the characteristic Greek abstracting tendency where divinity was concerned. The Diaspora produced the so-called liberal version of Judaism, which soft-pedaled, for the benefit of the goyim, those more exotic practices and taboos featured in Leviticus and Deuteronomy, while presenting Moses as a kind of enlightened philosopher, whose teachings were subsequently corrupted by bigotry, superstition, and obscurantism.25

This side of Judaism made a favorable impression on Hellenistic Greeks, who thought of the Jews as a race of philosophers (a view sustainable only by the failure to read anything they actually wrote: the same applies to the myth of Egyptian wisdom), and whose own increasing tendency, for example in the case of Isis (cf. p. 410), to universalize local deities and their attributes could quite easily embrace assertive monotheism, a process we can see beginning as early as Aeschylus’s day. Yahweh, being known as the “All-Highest,” hypsistos in Greek, was easily identified with Zeus, or, through his epithet Sabaoth, “Lord of Hosts,” etymologically confused with Sabazios. Alexandria both encouraged Jewish proselytization and facilitated the penetration of Judaism by Greek philosophical concepts, even to the point of deriving Greek philosophy from the Mosaic Law and interpreting the Torah in Hellenic terms.26

In Judaea itself Greek influences can be detected, for example in the “sceptical, pessimistic rationalism”27 of the Book of Qoheleth (Ecclesiastes),28 the third-century author of which not only bears witness to the existence of a vast bureaucratic hierarchy (5.7), but also reveals, prior to his all-flesh-is-grass reversion (e.g., at 5.10 f.), a highly Hellenistic, not to say Veblenish, preoccupation with the wealthy oligarch’s dream: the building of villas, the planting of vineyards and orchards, the acquisition of great parks and estates, the purchase of flocks and herds, the amassing of gold and silver via the exaction of revenue; casks of wine in the cellars, and a vast household of slaves, including singers, concubines, and catamites.29 By way of reaction we find the civilized and meditative anti-Hellenism of Ben Sira,30 whose Wisdom (more familiar to us by its apocryphal title, Ecclesiasticus) was composed between 200 and 180: about fifty years later his grandson translated it into Greek, which gave it a much wider circulation, above all in the Egyptian Diaspora.31

Joshua Ben Sira was no puritan by nature: he enjoyed good food and wine, was widely read and highly intelligent. Because of this he knew, all too well, the perils inherent in a free mind engaged upon intellectual inquiry, historia, and seeking answers to its questions by reason alone, unrestrained by taboo, dogma, or shibboleth. For him, a little wisdom with the fear of God was preferable to much wisdom without it (19.4), and his bitterest anger is reserved for those who cast aside the Mosaic Law in pursuit of ambition and undirected knowledge. Alien ways, he insisted, were dangerous for Judah: only under the Law of Yahweh could she triumph against her foes (47.4–7). The High Priest’s duties were to teach the Torah, to offer sacrifice, to make atonement on behalf of his people; by eloquent omission we are made to feel the perils attendant upon the exercise of this office by a Hellenizer.32 The materialistic lure of the Greek lifestyle is aptly summed up: “Feasts are held at will, and wine gladdens life, and money answers everything.”33 Ben Sira had traveled (51.13); he knew the wider world beyond the confines of Judaea. Despite this, he returned as orthodox as when he left: Greek culture was not for him. At the same time he understood, very well, the perilous chasm—in his own people as elsewhere—between rich and poor, though like so many other pious observers he took this to be immutable, and due to God’s will. There is a curious flavor of Stoicism about his advice to the downtrodden, whom he exhorts to pursue self-knowledge and wisdom as an answer to their quest for freedom.34 Rebellion and freedom fighting are not in his scheme of things, and we see, reading his work, why for so long Jewish nationalism lacked a revolutionary dimension.

Between 301 and 219 Palestine continued to be ruled by the Ptolemies in comparative peace (except for the capture of Samaria by Demetrius the Besieger in 296), since the various frontier wars did not penetrate that far south. From the Zenon papyri35 it seems clear that the same complex economic forces, the same strangling bureaucracy, the same military occupation that cluttered people’s lives in Egypt also operated here.36 Defense is a prime concern: we hear of cleruchies and fortresses, garrisons, grants of land to veterans. In 261/0 Ptolemy II’s officials organized the census, and taxation, of livestock in the area, and banned the acquisition of free Syrians or Phoenicians as slaves; it is further alleged that the king ordered the general manumission of all Syro-Phoenician and Jewish prisoners captured during his father’s campaigns in the area, but this is highly debatable.37 There is, however, no doubt that Jews found their way into the Ptolemaic administration, in both Egypt and Palestine.38 The father of Joseph the tax collector (of whom more in a moment), a wealthy magnate named Tobiah,39 held high rank in the Ptolemaic army: this is extremely significant, since in Egypt the Ptolemies shrank from giving any responsible office to native Egyptians, and the insurrections that followed their enrollment of Egyptian hoplites (above, p. 191), in an emergency, for the battle of Raphia (217) shows how sound this instinct was.

In Palestine, however, they needed indigenous support for their endless struggle with the Seleucids, and it was inevitable that the Jews themselves, certainly their leaders, should align themselves with one side or the other.40 Tobiah, like other Palestinian sheiks, was a man worth cultivating: in fact both he and his son maintained a firm loyalty to the Ptolemies, probably as the ruling power rather than through any natural affinity. There is evidence that in 259/8, when Zenon toured Syria, Phoenicia, Judaea, and Transjordan on behalf of the dioikētēs Apollonius, efforts were being made to organize the same kind of all-embracing bureaucratic estate management here as in Egypt.41 The larger the royal domains, the more authority had necessarily to be delegated; and despite the presence of resident Greek administrators, it was inevitable that Ptolemy, as absentee landlord (above, pp. 187 ff.), should entrust much of the day-to-day work to native officials. Local priests, aristocrats, or city magnates often acted as such liaison officers, remaining very much in de facto control.

Thus through the cleruchies and the Ptolemaic civil service the Jews came to acquire firsthand knowledge of Greek customs, proficiency in the Greek koinē, a taste for Hellenized names, even mixed marriages, and their initial approach to social Hellenization generally;42 while at the same time Jewish leaders were not only left in possession of their holdings, but co-opted into roles of political and administrative authority. Inevitably, there developed an alignment between the Ptolemaic (and, later, the Seleucid) government and a Hellenizing, collaborationist elite among the Jews. The latter’s political rivals thus tended to identify themselves, quite naturally, with a more strictly Judaic, anti-Hellenizing, noncollaborationist attitude: during the Seleucid regime they also sought, and obtained, aid from the Ptolemies, but largely in the traditional Jewish spirit of “My enemy’s enemy is my friend.” As Eddy says, “the history of the ruling circle was the aggrandisement of one noble or priestly faction at the expense of another,”43 a dichotomy exacerbated by the long-simmering conflict over Coele-Syria. Thus at a deeper level the ground was being prepared for a nationalist reaction against both Hellenism and foreign rule as such, which were, with some justice, seen as indistinguishable.

From 219, as we have seen (above, p. 288), Antiochus III made vigorous efforts to recover Coele-Syria and advance his frontiers toward Egypt: the following year he invaded Galilee, crossed the Jordan, and entered Samaria, but his defeat at Raphia forced him to postpone his plans for almost two decades. Then, between 201 and 199/8, he systematically reduced all the strongholds of Coele-Syria,44 and when the Ptolemaic forces evacuated the area this time, it was for ever. Palestine now became a Seleucid fief. Jerusalem, which changed hands twice during the fighting,45 finally expelled its Ptolemaic garrison in 198 and welcomed the new overlord, but not before it was clear beyond any doubt that Antiochus had in fact won.46

The events of these years suggest a sharp internal struggle between pro-Ptolemaic and pro-Seleucid factions in Judaea; Antiochus’s victory saw many of Ptolemy’s supporters (as had happened nearly a century before) beat a prudent retreat to Alexandria.47 This division is reflected in the generous terms that Antiochus negotiated for the status of the Jewish ethnos. His letter of concession is addressed not to the Jewish people, but to the governor of Coele-Syria, and pointedly omits any reference to the High Priest qua Jewish leader.48 This suggests that the latter was a Ptolemaic sympathizer, as indeed in terms of Realpolitik he would have to have been: changes of regime can be awkward for the functionaries of satellite nations.49 Willing cooperation with Antiochus—a splendid reception, lavish gifts of provisions and elephants—paid off. Seleucid bureaucrats were said to be easygoing;50 Jewish officials still untainted by Ptolemaic connections saw the glittering prizes of preferment within their reach.

Antiochus was certainly generous. Sacrificial animals, oil, wine, wheat, flour, salt, and incense, to the value of twenty-thousand silver drachmas annually, would be provided for Temple use. The Temple itself, damaged during the fighting, would be repaired, and all tolls waived on timber imported for it. These clauses perpetuated a long-standing tradition of subsidy by the ruler, going back as far as Darius (515) and Artaxerxes I (459).51 Citizens driven out or enslaved in the course of the war were to be reinstated in their former positions, and their property restored to them. Priests, scribes, temple singers (cantors?), and members of the council of elders were to be exempt from personal taxes in perpetuity, and the city as a whole tax-exempt for three years, with a subsequent reduction of liability by one-third. Most important of all, the Jews were guaranteed the right to live under their own ancestral constitution, that is, by the Torah. In another edict Antiochus reinforced, by the imposition of punitive fines, various Mosaic religious laws, including the ban on foreigners entering the inner court of the Temple, and that on the importing of animals regarded as unclean.52 Now it is unlikely that Antiochus knew, or indeed cared, about the Jewish way of life, being in this like most Greeks and Romans of all periods;53 but he undoubtedly understood what made for a lasting political settlement, and even if he did no more than initial a bill of particulars presented by the Jewish gerousia, as a quid pro quo for willing collaboration, it remains true that “the foundation was laid for the peaceful existence of the Jewish people under Seleucid overlordship.”54

The pro-Seleucid faction now came into its own. It has sometimes been alleged that this faction consisted ab initio of dedicated Hellenizers, who aligned themselves with a conscious policy of Greek cultural diffusion on the part of the Seleucids, but for neither of these suppositions is there any real evidence. The Seleucids were not proselytizers but exploitative imperialists (above, pp. 187 ff.), and their Jewish supporters in 198 were, as we might expect, acting from strictly political motives. The current High Priest, Simon the Just, seems to have led the pro-Seleucid group, and he could hardly be accused of Hellenizing tendencies. What he did do was rebuild the ruined city of Jerusalem, in accordance with Antiochus III’s guarantees. His main supporters were drawn from the elite: the priests, the aristocrats, the wealthy, who saw (even before 200) that the Ptolemies were a lost cause. What Antiochus offered them was a ratification of titular autonomy, that favorite Hellenistic device, the right to live as a more or less self-governing political entity within the Seleucid empire. Far from attempting to dragoon these people into Hellenism, Antiochus left them alone, under the enhanced authority of their own priests and religious laws. What we now have to figure out is just how and why, only thirty years later, Antiochus IV Epiphanes came to attack the Jewish religion and the Mosaic Law with such furious violence, banning circumcision and the observance of the Sabbath, instituting the cult of “Olympian Zeus” (or rather, a semisyncretized version of Baal-Shamin) in the Holy of Holies of the Temple in Jerusalem—acts not only in complete violation of his father’s policy, but also strikingly at odds with that general feeling for broadminded tolerance in religious matters that is one of the Hellenistic age’s most characteristic, and endearing, traits.55 Universal syncretism is hardly a convincing basis for iconoclastic bigotry. What, then, had happened?

Most of the popular theories (popular either in antiquity or among modern scholars) can be dismissed out of hand. Antiochus IV was certainly an odd, and perhaps in ways an unbalanced, character, with some of the habits of the later Julio-Claudian emperors (above, p. 437),56 but religious persecution per se had no charms for him. He was a professed Epicurean,57 and though he cracked down on the Jews, he left their neighbors in peace. The favorite modern view is that he was “the Helleniser par excellence,”58 using Hellenic culture to weld the heterogeneous mass of his empire into a cohesive whole, to eradicate superstition and promote Greek reason, and in the Jews alone found obstinate non-takers.59 Antiochus was certainly pro-Greek, but he was also, perforce, pro-Roman. His Hellenism was on occasion a useful political instrument, but he had not the slightest interest, any more than his father had had, in stamping out local culture as such, let alone in acting as a proselytizer for Hellenism, a role that is very largely a modern invention (cf. above, p. 324). A third suggestion is that he was imposing political unity by way of a single prescribed religion, syncretistic in its manifestations. But this kind of “pagan monotheism” was unheard of in antiquity till the third century A.D.

Antiochus’s coins suggest that he may have tried to organize his own worship in the avatar of Zeus or Helios (above, pp. 437–38), but that was nothing new; the only people liable to think of Antiochus’s imposed cult of “Olympian Zeus” as prescriptive monotheism were the Jews, who, as dedicated monotheists themselves, “saw in every tendency to prefer one cult over another an attempt to set up a uniform religion with the aim of abolishing the rest.”60 An amalgam of the preceding theories might suggest that Antiochus was simply exploring every available method to shore up his crumbling empire; but that does not tackle the problem of selective religious enmity. One last theory, that of Elias Bickerman in The God of the Maccabees,61 argues, correctly, that religious fanaticism of the kind displayed (or apparently displayed) by Antiochus was unparalleled in the ancient world,62 and from this infers that the real instigators of the purge were the Hellenizing Jews, the High Priest Menelaus and his supporters (below, p. 513), anxious to break down Jewish exclusiveness, so barbarian in the eyes of the Hellenistic world. But there is no evidence to connect this group with Antiochus’s decrees, nor indeed for their embracement of Greek philosophical ideas (as opposed to Greek social fashions: cucullus non facit monachum)—and if they had acquired them, why did they turn fanatic? They should have become tolerant liberals. Let us take a closer look at the background to the persecution.63

The Greek and Macedonian immigrants who had entered Palestine were not, for the most part, educated men, but rather—here as elsewhere—soldiers and settlers of relatively humble origin. Thus their intellectual impact on the area was small; what they brought with them were the externals of Greek city life, temples, gymnasia, the koinē, theaters—and, if theaters, then popular culture of a sort, probably enhanced by a smattering of the Greek poets taught in school (cf. above, pp. 319 ff.). But they were also quickly influenced by the indigenous population, and soon acquired what Greek purists referred to as a “mixobarbarian” culture, sacrificing to strange gods while building in Hellenic style: thinking Oriental, dressing Greek. What we have to explain is the fact that from the early second century a group of Hellenizers in Jerusalem not only achieved power, not only introduced Greek public mores (including the gymnasium and everything associated with it), but actually tolerated the influx of Greek cults into Judea, until the nationalists under Judas Maccabaeus reasserted the supremacy of the strict Mosaic Law.

In contrast to the Scribes, exegetes of the Torah, and closely associated with the strict sect of the Hasidim,64 who achieved new authority and power about the time that Antiochus III confirmed the Jews in their autonomy, there were other figures, very different yet equally symptomatic, who breached the old exclusiveness of the priestly caste by a candid reliance on Mammon rather than God. Of these perhaps the most notable was Joseph, son of that Tobiah who held high rank in the Ptolemaic army (above, p. 503). Quite apart from being Ptolemy II’s military representative in Transjordan, Tobiah had also hedged his sociopolitical bets by marrying the sister of the High Priest Onias II. He was, in addition, a business associate of Apollonius, Ptolemy’s enormously influential finance minister (dioikētēs: above, p. 386). His correspondence reveals a significant degree of Hellenization. His son Joseph thus grew up in a cosmopolitan Greek atmosphere; but he was also nephew to the High Priest. As a Transjordanian—and, worse, one who had dealings with the hated Samaritans—he must have aroused suspicion: his entire career was predicated on a conscious opposition to the kind of narrow ethnic and religious loyalties that were de rigueur among Jewish traditionalists.

Joseph son of Tobiah was, in fact, the prototype of the international financier for whom neither frontiers nor restrictive ethical considerations exist: he has been described (without any irony, I think) as “the first great Jewish banker.”65 At some point in the 240s he obtained, from Ptolemy III Euergetes,66 the office of prostatēs, which carried with it, inter alia, the responsibility for collecting taxes.67 This duty had previously been reserved to the High Priest in Jerusalem, who was held personally responsible for paying a lump sum of twenty talents,68 but lately had neglected to do so, an omission that made Ptolemy threaten to turn Judaea into military cleruchies, and look favorably on Joseph’s bid for the revenue contract. The post he sought was based not on theocratic privilege but on secular competence; it could, moreover, be expanded beyond the frontiers of Judaea proper (i.e., the former kingdom of Judah, little more than the city of Jerusalem with its chōra)69 to include the tax farming of all Coele-Syria, Phoenicia, Judaea, and Samaria.70 Joseph, in short, was offering to take over the fiscal control of the entire Syrian province, with the guarantee of a far higher return on it. Ptolemy accepted his bid, appointed him as prostatēs (he seems to have retained the position till 218),71 gave him a bodyguard, and backed him when, very early in his new career, he executed twenty recalcitrant officials in Ascalon who refused to pay taxes to this foreign interloper.72

Joseph cheerfully broke any Mosaic law in the line of duty: he dealt with Samaritans, he ate prohibited food at the king’s table, he dallied with Greek dancing girls. He also, more significantly, maintained a permanent agency in Alexandria, where large sums were on deposit at interest.73 The Hellenistic world beckoned alluringly, and he followed. Many of his more ambitious contemporaries got the message. To succeed as Joseph did meant, almost by definition, rejecting the narrow code of Judaism: there was no other way. And that, again almost by definition, meant embracing the ēthos of the conqueror. Here, in embryo, we can see the future ideology of the Jewish Hellenizing party: separatism had brought nothing but backwardness and trouble, whereas close cooperation, at every level, with the Gentiles would produce an economic and cultural boom.74

Joseph’s son John Hyrcanus likewise secured the tax-collecting concession, but, fatally, lacked his father’s diplomatic skills. He fought furiously with his brothers (ca. 200?), was forced back into Transjordan, chose the wrong side in the Seleucid-Ptolemaic conflict, and after some time as a petty desert chieftain, committed suicide rather than face Antiochus Epiphanes (ca. 175/0?).75 To set up an independent kingdom was in the classic Hellenistic tradition; so were Hyrcanus’s drinking parties, which recall those of Demetrius the Besieger (above, p. 50). Again, it was the trappings, rather than the essence, of Hellenism that most influenced both father and son: glittering social prizes for the upwardly mobile. Josephus—that wealthy Romanized Pharisee—claimed that Joseph brought the Jewish people from indigence to “a more splendid standard of living,”76 but in fact the Jewish people as a whole got nothing from the deal: it was a model for rich and well-connected go-getters only. Hellenism in Judaea, as elsewhere (above, pp. 315 ff.), had very little to do with culture. It was far more a matter of using the social status, the entrée, conferred by Greek public mores to further a ravenous appetite for wealth and power. Hence the animadversions of Ben Sira on haves and have-nots (above, p. 502). Hellenistic Greek towns were all around;77 the Greek koinē had become an indispensable lingua franca. From mint after local mint, good and abundant Greek coin issues testify to flourishing international trade.78

Joseph’s sons—that is, the five of them who survived in Jerusalem—emerged as leading figures in the Hellenizing movement:79 known collectively as the Tobiads, they later allied themselves with Menelaus, who succeeded Jason as High Priest under Antiochus Epiphanes (see below, p. 512), and his brothers, Simon and Lysimachus (the Hellenized names are characteristic).80 The Tobiads were vastly wealthy, in part by inheritance, in part as the result of their own financial activities. Inter alia they seem to have had control of the Temple treasury, and to have developed a promising new line in loan investment.81

But this is to anticipate slightly. A struggle for control broke out after the death, in 175, of the High Priest Simon II—known as “the Just,” and a powerful patron of the Tobiads—and the succession of his pro-Ptolemaic son, Onias III, a strict zealot.82 This conflict was resolved in the (pro-Seleucid) Hellenizing party’s favor as follows. Onias’s brother, Jesus, better known by his Greek name of Jason, went and petitioned the king—that is, Antiochus IV, Seleucus IV having just been murdered as the result of a court intrigue (175)—for Onias’s removal, well aware that this High Priest was already suspect in official circles (see below). By offering Antiochus no less than 140 talents over and above the prevailing tribute rate of 300 talents—in other words, by restoring the quota to its old Ptolemaic level—he in effect got the high priesthood by purchase, so that from now on the holder of that office became “a Seleucid royal official utterly dependent on the king’s favour.”83 The ease with which this mercenary deal was clinched on both sides reminds us that the Seleucids, too, had their problems, many of which (a common feature of the second and first centuries B.C.) were occasioned by Rome.

By now Antiochus III’s punitive indemnity after Magnesia (above, p. 421) had long been creating tensions in the increasingly unstable Seleucid empire, and it is interesting to observe the ways in which his heirs had gone about servicing the vast debt that they had inherited from him. The Temple in Jerusalem had already excited the cupidity of Seleucus IV, who, acting on information supplied by a disgruntled Jewish administrator,84 sent his minister Heliodorus to expropriate its funds and abolish its financial autonomy; he may also have intended to discipline John Hyrcanus, who had substantial cash deposits there.85 Heliodorus was refused access to the inner sanctum by the High Priest, Onias; Jewish tradition preserves an apocalyptic legend of his having been flogged senseless outside the treasury by a trio of handsome young angels in golden armor,86 a theme that, understandably, excited derisive skepticism at the time, but was later to inspire Raphael and Delacroix. Heliodorus’s empty-handed return angered Seleucus, and the king’s subsequent assassination may have been, in part, due to this imbroglio, since Heliodorus, anxious to prevent his own dismissal, if not demise, was responsible for it. Seleucus also noted, for future reference, the obstructive attitude of the High Priest in refusing his minister’s request, a lesson that was not lost on his successor. Antiochus IV therefore at first took the simple step of buying himself a more compliant High Priest; it was only later, under considerable stress (below, p. 513), that he turned to simple plunder and rapine.

What Jason also obtained at his famous interview with Antiochus, reportedly by the offer of yet another 150 talents, was the authority to build a gymnasium, to organize training for a corps of ephebes (ephēbeia)—both classic elements in Hellenistic higher education, such as it was—and to “register the Antiochenes in Jerusalem,” a phrase that has been interpreted in different ways.87 From a careful reading of the main sources it becomes clear that the object of this move was systematic Hellenizing propaganda, sociocultural and antitheocratic in tendency, but limited to an elite group and thus civic only in a highly modified sense.88 Whether the petitioner was Jason or, as Josephus suggests, Menelaus backed by the Tobiads, the privileges requested are for a special minority group. It is they, not the Jews as a whole (or even the citizens of Jerusalem), who express the desire “to abandon their country’s laws and the politeia enjoined by these, and to follow the royal laws, and adopt the Greek politeia.”89 It is they, not the majority, who hope to be registered as “Antiochenes” (i.e., Hellenized inhabitants of a Hellenized and renamed—for them—“New Antioch”), to exercise à la mode grecque, to form a select club of progressive Hellenizers, to which their adolescent sons would be admitted only after passing through that rigorous two years’ training, both military and athletic, provided by the ephebic system.

This point is worth stressing, since it has been forcefully argued,90 and widely accepted, that what Jason asked for, and got, was the transformation of Jerusalem, by fiat, into a full-blown Greek polis, a thesis for which there is no compelling evidence. Indeed, it is hard to see how, in practical terms, so unprecedented a change could have been imposed, not least since Jerusalem remained under priestly rule throughout. There was not, as yet, any hint of interference with Jewish religious practices (except insofar as the sale of the high priesthood and the introduction of Greek fashions could be held, per se, to constitute offenses against the Jewish faith), and at the time of Antiochus IV’s famous letter rescinding his religious persecution91 the Jews were clearly still regarded as an autonomous, if tributary, ethnos.92 At the very most, it seems clear, what Jason envisaged was a privileged enclave, a Greek-style politeuma within the Jewish theocracy; and probably no more, in fact, than the creation of a specially favored cosmopolitan class dedicated to social and political self-advancement via the promotion of Hellenism.93

In this latter aim, however, he enjoyed, for a year or two, a certain succès de scandale. Antiochus cheerfully authorized the “Antiochenes” to “perform the rites of the heathen.”94 The gymnasium was built on the Temple hill, below the fortress, and crowds of young men, wearing the broad-brimmed hat (petasos) of the ephebe, among them some priests who had abandoned their more decorous Temple duties for the lure of naked athletics (in particular discus throwing), now began to exercise with the enthusiasm of converts.95 For many the urge to break away from the isolation imposed by strict Judaism had become very strong. However, these impassioned would-be Greeks had one embarrassing problem to overcome: the highly un-Greek fact of their circumcision. In one scholar’s delicate phrase, they “employed artificial means to efface it.”96 Just how they “concealed” or even “removed” evidence of the mohel’s knife is not at all clear.97 All we know is that a surprising number of people did so.98 Yet there were some aspects of Hellenization that still caused qualms to Jews, however liberal in their beliefs and practices. When Jason sent a delegation of “Antiochenes” to Tyre, with a cash offering to Heracles-Melkart on the occasion of the quinquennial games instituted by Alexander,99 the syncretistic gesture misfired: his emissaries, unable to stomach the idea of placating a heathen god against whom Elijah and Elisha had triumphed, arranged for the sum—three hundred silver drachmas—to be applied instead to the construction of triremes.100

Oddly enough, in all this there does not seem to have been any technical violation of the Mosaic Code.101 Athletic games and physical training might not be in the spirit of the Torah, but Moses had never specifically banned them: neither Egypt nor the wilderness had forewarned him of this eighth plague. Nor at the time did conservative exegetes have the ingenuity of those Victorian nonconformists who quoted Psalm 147 (“The Lord sets no store by the strength of a horse, neither does he delight in a runner’s legs”) to get racing and football banned on Sundays. The rationale, the program of the Hellenizers is reported in these words: “Let us go and make a covenant with the heathen round about us; for ever since we separated from them, many evils have found us out.”102 What the “Antiochenes” sought was sociopolitical privilege and status, better cosmopolitan communications, above all with the Seleucid court. Antiochus, for his part, was by no means loath to have a friendly, obligated, influential elite in a city of this size and power, so strategically placed near the southern frontier of his empire. The concession for which he was asked cost him nothing, and nothing but good (he must have reasoned) would come of it.

So from 175/4 to 172/1 Jerusalem, though officially under sacerdotal rule, enjoyed—to the scandal of the pious and the great delight of her progressives—a brief efflorescence of fashionable Hellenization, mainly restricted to the more obvious and external features associated with that phenomenon. However, its leader turned out to have, despite everything, the remnants of a Jewish theocratic conscience, and this proved his political undoing. Jesus might rename himself Jason, but he was still of the High Priest’s line, and thus there were some things that he, unlike the Tobiads, could not quite bring himself to do: plundering the treasures of the Temple was one of them. When Antiochus, like Seleucus, demanded access to them (171), Jason proved as adamant as Onias. Perhaps he was banking on the credit he won by his splendid reception of the Seleucid monarch in 172, when Antiochus had come down from Joppa to be welcomed by cheering crowds and a great torchlit procession.103 If so, he miscalculated badly. Antiochus needed that money; and the Tobiads, who were determined to keep in with the king, and had more realistic notions than did Jason of how this end could best be achieved, meant to see that he got it.

They therefore decided to get rid of Jason, and to replace him with their own candidate, another Hellenizer, who called himself Menelaus (his Jewish name is uncertain). Being from the tribe of Benjamin,104 Menelaus was not of priestly descent, and might thus be expected to have more accommodating moral standards. He already enjoyed some kind of official position, since he was now sent by Jason on a mission to Antiochus; but the Tobiads had primed him well for his interview, at which he dealt with Jason precisely as Jason himself had dealt with Onias III. Knowing well that the king’s shortage of funds was the crucial issue, Menelaus simply outbid Jason by three hundred talents for the office of High Priest, and was appointed on the spot.105 Jason refused to budge, and civil war broke out. Finally ejected, he sought refuge in Transjordan, and the pro-Seleucid extremists took over. The common people, acquiescent under Jason’s moderate regime, very soon turned against Menelaus and his backers, who were imposing ever higher taxes to meet their expensive obligations. Genuine religious outrage also played its part. The last straw was when Menelaus, under pressure after failing to pay Antiochus the sums he had promised (the king was showing ominous signs of impatience),106 embezzled gold vessels from the Temple in order to bribe high officials in Antioch, and, in desperation, also had the deposed Onias III assassinated (170).107 So died the last legitimate Zadokite High Priest. Further sacrilegious pilfering took place. Fiery apocalyptic propaganda whipped up the Jerusalem mob: Menelaus’s brother and deputy, Lysimachus, was killed, and his private army scattered, in a savage street battle. Menelaus somehow suppressed this popular uprising, bribed his way back into Antiochus’s favor, and “as a great enemy of his countrymen” held on to the high priesthood.108 It is against this lurid background that we must consider Antiochus’s subsequent persecution of the Jews.109

The precise course of these events, in particular the chronology between 169 and 167, has been much debated.110 How many times in that period did Antiochus Epiphanes enter Jerusalem? When, precisely, did Jason stage his counterattack from Transjordan? Do the accounts in 1 and 2 Maccabees duplicate incidents that in fact only happened once? Given the nature of our testimony it is unlikely that agreement will ever be reached on all these points, let alone on the motives of each protagonist in the drama. What follows is, like all previous versions, an attempt to reconstruct historical developments through a critical reexamination of admittedly recalcitrant evidence. Like them, too, it cannot claim to be more than a provisional hypothesis.

Late in 169, after his first expedition to Egypt (above, p. 430), Antiochus Epiphanes entered Jerusalem, with his army, on his way back north to Antioch. He was, as always, short of money, and the object of his visit was to raise some quick loot. The plundering of sanctuaries had become a common habit since Antiochus III had embarked on it (above, p. 422), and Epiphanes himself was no stranger to the practice: his death followed an abortive attempt to sack the same rich temple in Elymaïs (Elam).111 He now improved on Menelaus’s ad hoc pilfering by removing a substantial amount of treasure from the Temple; since he later returned to complete the job more thoroughly, there is a certain confusion in our sources between the two occasions.112 There was no open uprising at the time, but Antiochus’s actions left a legacy of deep hatred and resentment behind, and not only among strict traditionalists: what the king regarded as no more than catching up on arrears of tribute, and, thus, his royal prerogative, appeared in Jewish eyes as plain sacrilege.113

During Antiochus’s second Egyptian campaign, in 168 (above, p. 430),114 a false rumor that the king was dead reached Jerusalem, and encouraged Jason to launch an assault against the city from his base in Transjordan. At the head of a thousand men he broke through the defenses, forcing Menelaus to seek temporary refuge on the acropolis. Jason slaughtered large numbers of his opponents, which was probably a mistake, even though he seems to have had the anti-Hellenist majority of the population solidly behind him.115 Menelaus and his supporters, the Tobiads prominent among them, fled from Jerusalem to Antiochus, with a convincing tale of pro-Ptolemaic insurrection116—convincing, because Alexandria was the natural place for any anti-Seleucid faction near Coele-Syria to turn to in search of backing. Indeed, when Antiochus afterwards sacked the city, he is said to have killed “a large body of Ptolemy’s supporters.”117 This report of disaffection could hardly have reached the king at a worse time. After a successful Egyptian campaign he had been abruptly checkmated, and, worse, insulted, by Popillius Laenas, the autocratic Roman envoy (above, pp. 431–32): the notorious Day of Eleusis, the memory of that humiliating circle drawn round him in the dust, cannot have left him in anything but a mood of black fury and frustrated vengefulness. It hardly needed the urging of Menelaus or the Tobiads to make him take vigorous reprisals against the rebellious city.118

Whatever had happened during his earlier visit paled into insignificance beside the bloodbath that now took place. Jason, fearing to face a Seleucid army, prudently fled before Antiochus’s arrival; but Ptolemy IV, who knew all about his pro-Seleucid past, refused him asylum, and he was forced to move from city to city, finally dying as an exile in, of all places, Sparta.119 He was luckier, even so, than those who stayed to face the wrath of Antiochus Epiphanes. The king is said to have set out from Egypt “raging like a wild beast.”120 He took Jerusalem by storm, aided by the treachery of his Jewish supporters, who opened the gates to him.121 His soldiers were given instructions to spare no one, young or old, man, woman, or child: they also had carte blanche to plunder the city.122 The only figures at our disposal show a total of eighty thousand killed in three days, half of that number in hand-to-hand fighting, and as many more again sold into slavery.123 Accompanied by his creature Menelaus, Antiochus entered the Temple, and stripped it of all remaining sacred precious vessels and ornaments, including the golden candelabra and altar top. He took besides accumulated bullion to the value of eighteen hundred talents.124 Then he returned to Antioch, leaving two overseers (epistatai), as well as Menelaus, in charge of the stricken city.125

There must have been continued rebellion despite these savage punitive measures, since in 167 Antiochus sent to Jerusalem a second expeditionary force, commanded by a Mysian officer named Apollonius. Though the atrocities attributed to Apollonius sound suspiciously like doublets of those committed by Antiochus’s troops, he did (like Ptolemy I) occupy Jerusalem on the Sabbath, when the inhabitants were not bearing arms; he then proceeded to tear down the city walls, and to build, probably on a spur opposite Mt. Zion, south of the Temple, in the old city of David, an impregnable fortress known as the Akra, garrisoned with non-Jewish military settlers, a refuge for Hellenizers, and—despite all the successes of the Maccabaean faction (see below)—a safeguard of Seleucid rule for almost three decades, till Simon finally won control of it in 141 (p. 523).126 It is worth noting that despite his military activities, Apollonius’s official title was that of chief tax collector,127 and thus we may assume (what all our other evidence confirms) Antiochus’s concern with Judaea to have been at least as much financial as strategic. Indeed, Antiochus may well have introduced the new proportional land tax that replaced the old fixed-tribute quota—another source of resentment, since by 153 the quotas seem to have been one-third of the grain produced and no less than half the fruit.128

Antiochus’s motivation at each stage, in fact, seems comparatively straightforward, and reveals throughout the usual Hellenistic ignorance of, or indifference to, the powerful forces—isolation, monotheism, exclusionary pride in their history and religious laws—that shaped and sustained the Jewish people. He badly needed funds; he was anxious about the security of Coele-Syria. All his actions in Judaea to achieve these ends ran into a very special kind of religious-inspired ethnic resistance. Other victims of temple robbery merely grumbled (or, if they were desperate, killed the robber); the Jews cried sacrilege and prepared to fight en masse, often vanishing into the countryside for the purpose, a form of passive resistance known as anachōrēsis, which could easily be escalated into guerilla warfare, and also offered good opportunities for avoiding taxation.129 Seleucid divide-and-rule tactics might generate rivalry between Hellenizers and traditionalists, but in the last resort the latter were stronger, and more numerous, and more passionate in their beliefs: they stood firm in the face of odds, and were prepared to make sacrifices, indeed to die, for what they held most dear. Even the most energetic and seductive Hellenizing propaganda failed to soften the vast majority of Jerusalem’s religious fanatics, just as massacres, far from breaking their spirit, simply stiffened their will to fight.

Antiochus, who himself was by no means insensitive to the value of theocratic self-promotion (above, p. 438), must very soon have perceived that his stumbling block in Judaea, what nullified his efforts at every level, was, precisely, this Chosen People’s fierce and exclusive faith. How far active resistance had yet broken out is uncertain,130 though the garrisoning of the Akra must have done much to bring discontent to a head. At all events, during 167 Antiochus made every effort to crush Jewish resistance by eradicating the Jewish faith. The method he chose, that of violent coercion, represented a more than usually gross error of judgment; but taking into account his naturally autocratic temper, in conjunction with the exploitative atmosphere in which he had been raised, it is very hard to imagine him trying a more conciliatory approach—not, that is, until he had finally learned, the hard way, that coercion in this case was something worse than counterproductive, a lesson that went against the grain of every Ptolemaic or Seleucid principle of government.

He was also, it is clear, strongly supported in the measures he now took by the Hellenizing party under Menelaus and the Tobiads. Their antinomian position could only be regularized by a complete jettisoning, indeed extirpation, of the old Law. It has been argued that the initiative came from them in the first place (above, p. 506), since, inter alia, the persecution was purely local, and did not apply to the Jews of the Diaspora (who were, in any case, of a more liberal disposition).131 This is mere speculation. I am equally skeptical of the suggestion that what Menelaus and the “sons of the Akra” hoped to enforce was a new, liberal tolerance on the part of the unenlightened,132 an early version of the principle sois mon frère ou je te tue. Both for Antiochus and the “Antiochenes” the true issue at stake was that of economics combined with power politics: increase of revenues, defense of Seleucid frontier interests.133 Religious syncretism had long been recognized as a useful instrument of political unification, and Antiochus’s enhanced title “God Manifest, Bearer of Victory” (Theos Epiphanēs Nikēphoros), duly inscribed on his coinage from 169/8,134 bore witness to this, as did his marked interest in the cult of Olympian Zeus (or his local avatars),135 and his self-identification with Helios, the royal and all-seeing Sun (above, pp. 437–38).136 It is in this context that we must consider the king’s edict, allegedly promulgated throughout his kingdom, ordering that “all should abandon their local customs and become one people.”137 Even if this report is true (which has been doubted), the viewpoint of the reporting may well be local and Palestinian, and not refer to the Seleucid empire as a whole. “All the heathen accepted the decree.” All? More interesting is the fact that “many from Israel” did so.138

But about the edict of religious persecution there can be no doubt: it was directly aimed at Jerusalem and Judaea,139 where it was hand-delivered in written form. The neighboring Greek cities of the region were likewise required to enforce it, but this would seem to have been the limit of its applicability.140 The Jews of Samaria protested to the king that they really traced their origin from Sidon, and—a nice touch of sardonic realism—that if they were left in peace they would find it easier to pay their taxes. They also offered to dedicate their temple to Zeus. Antioch granted their petition: this was the kind of reaction he was used to, the rationale behind the commands he now sent to Judaea and its environs.141 All he aimed to achieve was the elimination of a rebellious local group by abolishing the ideological code that sustained it. This was why, even within the Seleucid domains, the Jews of Babylonia and northern Syria remained unaffected.

But in Judaea itself, under the king’s further edict, all Jewish rites and observances, those of the Sabbath included, were to be done away with, as evidence not so much of superstition (though this was alleged too) as of offensive separatism.142 The Books of the Law, the Torah, were to be torn up and burned. There were to be no more sacrifices or burnt offerings or drink offerings in the Temple. The death penalty was decreed for a whole range of offenses: possession of the Jewish scriptures, nonconformity with Greek customs,143 observance of Jewish religious law, and, in particular, the practice of circumcision. Mothers of circumcised male children were thrown off the city walls with their babies strung round their necks; not only the circumcisers, but their entire families were executed.144 In addition to these negative prohibitions came positive injunctions. The Jews were to set up Greek-style altars, images, and sacred groves, to sacrifice pigs and ritually unclean cattle, to eat pork145— a peculiarly vindictive requirement, since it was by no means the Jews alone who regarded this animal as impure146—to worship Hellenic gods, to celebrate the king’s birthday with monthly offerings, to walk ivy-wreathed in procession during the biennial festival of Dionysus. In December 167 the Temple was rededicated to “Olympian Zeus,” that is, the Syro-Phoenician Baal-Shamin,147 whose Hebrew name verbally echoes the “abomination of desolation” in the Book of Daniel.148 The placing of a small heathen altar of burnt offerings in the Holy of Holies, and the slaughter on it, ten days later, of a pig, can be seen as a deliberate affront to Jewish religious separatism.149

Reaction was instant and violent. Though many complied under duress,150 many more did not. One road to follow was that of conscious martyrdom, and some striking instances are on record.151 Another was the withdrawal into the wilderness (anachōrēsis), leaving fields untilled and taxes unpaid, a passive resistance naturally treated as rebellion by the authorities. Such fugitives were hunted down and, where possible, killed, a task made easier by the fact that strictly orthodox Jews would still not raise a hand in their own defense on the Sabbath, and thus, if caught, could be slaughtered with impunity, like cattle.152 In such circumstances of harsh repression, which struck at the deepest spiritual convictions of an entire people, it was inevitable that, sooner rather than later, a nationalist guerilla movement, of the type we have come to know so well today, should crystallize around some charismatic leader. All that had been won in centuries of Jewish history—and confirmed by the edicts of Antiochus III—was now at hazard. The aim of the Hellenizers, to bring Judaea out of political and cultural isolation into the mainstream of Near Eastern (which meant Seleucid) civilization, seemed a wholly inadequate return for the loss of monotheism in Yahweh and Yahweh’s Law.153 Better death in action than a shameful compliance.154 Were not the Syrian and other foreign troops in Jerusalem making blasphemous sacrifices to Baal-Shamin, and filling the Temple courts with sacred (or not so sacred) prostitutes?155 The time was ripe for action; and the time duly called forth the man.

The spark for insurrection was provided by the action of a priest, Mattathias, of the Hasmonean family,156 in the village of Modein (el-Medieh), northwest of Jerusalem, near Lydda.157 A royal officer, Apelles, arrived to supervise, and enforce, heathen sacrifice on the part of the villagers. He appealed to Mattathias, as a local leader, to set a good example that others would then follow. Mattathias refused, with a ringing reaffirmation of his faith,158 and, when a less defiant Jew came forward to make the sacrifice, killed both him and Apelles, after which he overthrew the altar. “Let everyone,” he cried, “who is zealous for the Law, and would maintain the covenant, follow me.”159 Then he and his five sons—John, Eleazar, Simon, Jonathan, and Judas, known as Maccabaeus (probably “the Hammer”)160—took off into the Judaean hills. Here they heard of the deaths of a thousand fugitives who had refused to defend themselves on the Sabbath, and took the momentous decision that, in upholding the covenant that God had made with their forefathers, they were prepared to fight on all seven days of the week.161 Reinforced by the strict and populist Hasidim, a sect that provided their movement with both the apocalyptic inspiration and the ideological purity that it needed,162 Mattathias and his rapidly growing band of followers embarked on a kind of religious razzia, preaching open resistance, killing apostates, burning their towns and villages, tearing down non-Jewish altars, and forcibly circumcising all uncircumcised male children. In the matter of intolerance there was, clearly, very little to choose between them and their persecutors; at times one begins to feel a certain sympathy for the much-despised Hellenizers.

This vigorous program proved too much for the elderly Mattathias, who died that same year (166), full, if we can trust our sources, of edifying rhetoric to the last.163 His importance in the rebellion has probably been exaggerated. With the assumption of military command by his son Judas Maccabaeus insurrection entered upon a new phase: it became a highly politicized revolutionary war, challenging the Seleucid regime and aiming, ultimately, at complete independence for the Jewish ethnos. Judas was a natural general, who welded a heterogeneous mass of untrained followers, in a remarkably brief space of time, into a formidable fighting force, over six thousand strong. He not only showed a flair for guerilla tactics, but proved himself capable of winning pitched battles. He fought Apollonius the tax collector (above, p. 514), now governor of Samaria and Judaea, defeated and killed him, and took his sword to use in all future engagements.164 Another Syrian officer, Seron, was put to ignominious flight.165 It was now that Antiochus Epiphanes, anxious to embark on his eastern campaign against the Parthians (165), set out from his capital, leaving his viceroy, Lysias, to deal with, among other things, the Jewish rising (above, p. 439).166

Lysias instructed the governor of Phoenicia and Coele-Syria, Ptolemy son of Dorymenes, and Philip, the royal epistatēs in Jerusalem (above, p. 440), to take appropriate military action. Their combined forces marched south, only to be outmaneuvered and defeated in the rugged hill country of Judaea.167 At this point Lysias decided he had no alternative but to put down the rebels himself. In the autumn of 165 he brought Judas to battle near Beth-Zur, south of Jerusalem, and fared little better than his predecessors, being defeated (though not annihilated) and forced to retreat to Antioch in search of reinforcements.168 Here, however, on reflection, he came to the conclusion that he would—for the present at least—get farther, and with less effort, by negotiation. He therefore sent a conciliatory dispatch to Judas, promising to use his best offices with Antiochus to obtain a just settlement.169 Probably in November, a petition from Judas, embodying some of Lysias’s suggestions, was forwarded to Antiochus in the east. It is noteworthy that the envoy who delivered it, and argued the Jewish case, was Menelaus, still officially High Priest and the representative of Seleucid authority in Jerusalem. Thus, in his dealings with Judas, Lysias was, as Marxists would say, involved in a contradiction. The conflict between Hellenizers and Jewish traditionalists was on hold for the moment—the edict of persecution had seen to that—but very far from resolved.

Early in 164, in response to this diplomatic démarche, a remarkable document from Antiochus reached the Jewish gerousia. It contained an amnesty for those guerillas who returned to their homes by a certain date, and a pledge that henceforth the Jews would be permitted to revert to their own laws and dietary code (or, perhaps, system of taxation).170 Antiochus clearly had the good sense to realize when a policy was proving disastrous, and to reverse it; but his persistence in dealing only with Menelaus and the Hellenizers shows either that he still did not fully understand the Jewish problem,171 or, more probably, that he understood it very well, and was playing a long-term game, making what were to him unimportant concessions, while at the same time not losing any substantial power. His letter made no mention of the high priesthood, no reference to control of the Akra. Perhaps his immediate aim was to put a stop to the fighting, in which Judas had been all too successful: to buy time. Political realignments, if unavoidable, could come later. Lysias had, it is clear, presented forceful pragmatic arguments in favor of a change in policy, which Menelaus (with whatever private misgivings) duly conveyed to the king. It is no accident that for the rest of 164 there would seem to have been a complete cessation of hostilities in Judaea. The insurgents, whose long-term ambitions had been heightened, and politicized, by success, used this time to build up their reserves and, almost certainly, to restore the country’s disrupted agricultural life.172

Judas Maccabaeus had won the first round, but much still remained to be done. Political ambition and religious zealotry fused in him to form an explosive driving force. From now on, two objectives were clear in his mind: the purification of the priesthood (or, put differently, the removal of the High Priest’s office from the Hellenizing party), and the reestablishment of Judaea as an independent, sovereign state. These two goals were, of course, indissolubly linked. Hellenizing High Priests such as Menelaus not only represented the “sons of the Akra”; they were the appointed spokesmen and instruments of Seleucid policy. Similarly, to free Judaea from foreign overlordship meant, inevitably, a return to that strict separatism demanded by the Torah. But over and above these high motives we can also detect something more familiar, more mundane: the unmistakable appetite for power. The Hellenizers, as we have seen, enjoyed substantial support, by no means all of it from wealthy progressives or collabos. The smell of intellectual and cultural freedom can be intoxicating, especially to the young: our own age can provide parallels and to spare. Thus while the Hasmonean brothers were indeed fighting a religious war of liberation in 165, they were also—like Jason, like Menelaus—increasingly engaged. as time went on, in a fratricidal struggle for the high priesthood, and, thus, in a separatist theocratic state, for supreme political power.173 All subsequent events— culminating in the establishment of the Hasmoneans as hereditary High Priests of Israel (below, p. 524)—must be scrutinized with this consideration in mind.

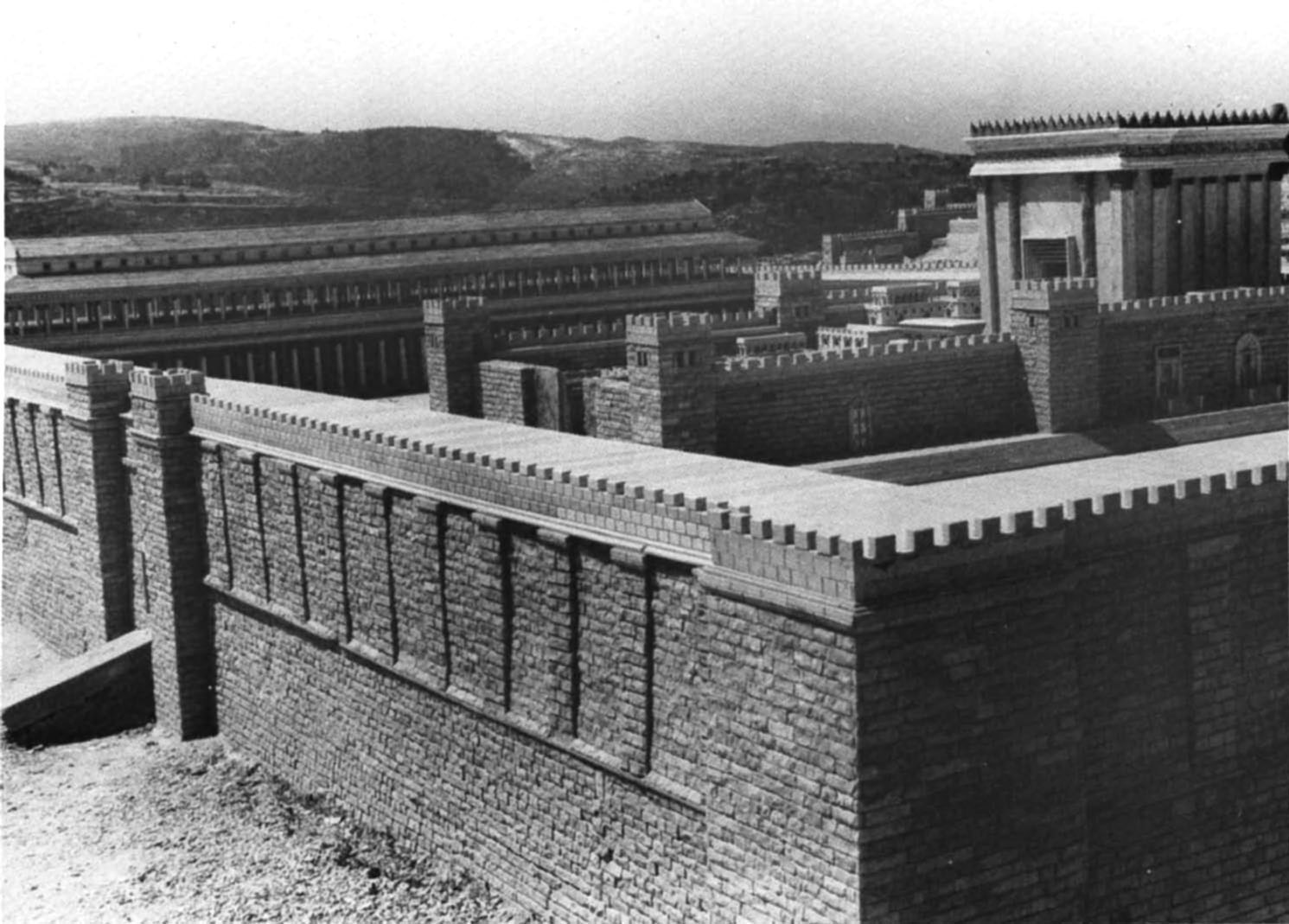

Judas’s next move was a master stroke, combining impeccable piety with immensely potent symbolic propaganda. In October or November of 164 he and his troops marched into Jerusalem with one object in view:174 the rebuilding, purification, and rededication of the Temple, according to strict Judaic law.175 They found the gates burned, the sanctuary desolate, the altar profaned, weeds sprouting in the courts. Liberal polytheism had done its worst. Antiochus’s letter had, wisely, not attempted to adjudicate between Jewish religious rivals; so while the work of reconstruction went on, Judas’s guerillas stood guard to prevent any untoward interruptions by the Hellenizers’ Syrian garrison in the Akra. The heathen altar was removed, its defiled base dismantled, a new one of uncut stones set in its place. New doors were fitted, new sacred vessels of gold consecrated. On 25 Kislev, in December 164, the lights were kindled, the shewbread set out, incense burned, sacrifice offered; for eight days of ceremonial rejoicing—still repeated annually as the feast of Hanukkah—the restoration of the Temple brought joy to the hearts of the faithful, emphasized (as nothing else could have done) the triumph of the Torah over liberalism, and associated that triumph indissolubly with the Hasmoneans. It was Judas Maccabaeus’s finest hour, the high point of his achievement. Yet it also, inevitably, heralded his decline and fall. With the religious phase of the struggle accomplished, Judas’s role now became that of the politically ambitious rebel guerilla, lured on by apparent weaknesses in the Seleucid military machine.176 As he was soon to find, this course had its moral no less than its physical hazards.

The first step he took after the purification of the Temple was to fortify Mt. Zion and the southern border city of Beth-Zur, facing Idumaea.177 In 163, with Antiochus IV dead, and Lysias holding an uncertain regency on behalf of the king’s nine-year-old son, Antiochus V Eupator (above, p. 439), Judas felt safe to go on the offensive again: the Syrian government had more pressing concerns just then than interstate feuding in Palestine. He spent the spring and summer in a series of vigorous local campaigns: how far these were provoked by harassment from the king’s garrison commanders, as our Jewish sources allege, is problematical.178 Jewish minorities were successfully evacuated from Gilead and Galilee. Hebron was besieged and destroyed. Judas invaded the land of the Philistines, justified his aggression by much ostentatious destruction of altars and idols, and came back laden down with valuable loot. The toll in lives, plunder, and ruined property was heavy. Judas’s policy hardly increased the good will of neighboring states such as Idumaea toward Jerusalem, and his now-open defiance of Seleucid overlordship caused serious alarm in Antioch.179 This situation was further exacerbated by the passionate anti-Seleucid propaganda that, inevitably, now began to circulate, the most notable example being the Book of Daniel.180 In Sehürer’s words, “it was quite clearly no longer a matter of protecting the Jewish faith but of consolidating and extending Jewish power.”181 The farther Judas moved in this direction, of course, the less likely any Seleucid ruler would be to reach an accommodation with him: he was rapidly taking on the lineaments of that perennial Hellenistic bogeyman, the nationalist troublemaker, the subverter of established law, order, and social privilege.

These new and alarming moves culminated in a direct assault against the Syrian garrison of the Akra, which Judas now placed under siege (163/2).182 Some of the garrison escaped and, accompanied by Menelaus the High Priest, took their complaints to Lysias in Antioch. Lysias and the boy-king Antiochus V moved south with a powerful Syrian army: Judas suffered his first serious defeat, his brother Eleazar was killed on the battlefield, the fortress of Beth-Zur was stormed and taken, and Jerusalem itself placed under siege. Since it was a sabbatical year the defenders had inadequate rations, and it looked as though Lysias was on the point of scoring a major victory against the nationalists.183 Unfortunately for him, it was at this precise moment (summer 162) that he found himself threatened with replacement by Antiochus IV’s general Philip (above, p. 439), and was thus forced to raise the siege of Jerusalem with more haste than dignity. To save face he had Antiochus V sign a document that confirmed his father’s concessions to the Jews, endorsed (after the event) the return of the sanctuary to its original state, and expressed a pious hope that “the kingdom’s subjects should be undisturbed in the pursuit of their own affairs,” a singularly mild admonition to Judas Maccabaeus concerning his new policy of military aggression.184 The absence of political endorsement is predictable. On receipt of this document the defenders withdrew from Mt. Zion, and Lysias—in contravention of his oath—pulled down the fortifications before returning to Antioch, where, as we have seen (above, pp. 440–41), he and the boy-king Antiochus, after some initial successes, soon fell victims to Seleucus IV’s son Demetrius.185

One positive, and somewhat unexpected, action Lysias had taken during this expedition was the execution of Menelaus, whom he had identified as “the cause of all the trouble,”186 a view with which Judas would doubtless have agreed, but which suggests that what Lysias objected to in this oversubservient High Priest was not so much his strength as his fatal weakness. His removal did not imply a shift in policy, since Lysias at once replaced him with another Hellenizer, Yakim, or Jehoiakim, known by his Greek name of Alkimos.187 This was only logical. So long as the Hellenizing party had the support of the Akra garrison, and enjoyed even a modicum of popular support,188 no Seleucid minister in his right mind would abandon it in favor of a separatist state headed by a fighting zealot like Judas Maccabaeus. This should be remembered when we are tempted to criticize Antiochus IV and his successors for clinging to a policy that we, with the advantage conferred by hindsight, can see as doomed to failure from the start. Lysias had in fact chosen Alkimos with some care. There was nothing amiss with his priestly pedigree:189 he could, indeed, claim descent from Aaron, and his legitimacy was at first recognized even by the Hasidic pietists.190 Opposition, predictably, was limited to Judas and his adherents, who claimed that only they could guarantee true religious freedom.191

What followed was a naked power struggle of the kind in which Hellenistic history abounds: there is nothing specifically Jewish about it. The siege of the Akra might have failed, but Judas kept up a relentless pressure against his rivals. Alkimos and others of his party went up to Antioch, where they regaled the newly crowned Demetrius with lurid tales of Judas’s pogroms against them.192 Demetrius, in this if nothing else like Antiochus, had no taste for troublemakers. He not only confirmed Alkimos as High Priest, but sent an army under his lieutenant Bacchides to restore order, protect the Akra, and see Alkimos safely established in his priestly-cum-political office.193 The result was more trouble. Despite their oily assurances that they came in peace (which were, at first, taken at face value, in view of Alkimos’s priestly antecedents), Alkimos and his backers lost no time in arresting, and executing, sixty of the Hasidim who had assembled to “seek justice,” that is, to put forward proposals for the new regime.194 At first sight this seems incomprehensible: why alienate one’s supporters? But by no means all the Hasidim did in fact back Alkimos—indeed, as we have seen (p. 517), they started out pro-Maccabaean—and later Alkimos himself identified them to Demetrius as active revolutionaries under Judas’s leadership.195 Josephus claims that these executions were a deliberate deterrent, to discourage desertions to Judas.196 If so, they were predictably counterproductive. What is absolutely clear is that Bacchides and Alkimos were committed ab initio to the eradication by force of Judas and his supporters, and killed Maccabaeans without compunction wherever they found them.197 Religious rights were one thing—the concessions made had come to stay—but an independent, and hostile, Jewish regime was quite another.

Judas, who had wisely refused to meet either Bacchides or Alkimos on their arrival, also contrived, despite Alkimos’s Syrian army, to debar the new High Priest from setting foot in the Temple, a notable propaganda victory.198 Open warfare now ensued between the rivals, with further appeals by Alkimos to Antioch for support (Bacchides had already returned there). A great victory by Judas in 161 was followed up by his petition to the Roman Senate for a treaty of alliance, this by now being the acceptable mark of international recognition: the treaty appears to have been secured (above, p. 441), though, as usual with Rome on such occasions, it was “a ceremonial convention, not a plan for military action.”199 A routine pro forma warning to Demetrius from the Romans to refrain from hostilities against Rome’s allies, the Jews200—if in fact it was ever delivered—was anticipated by Demetrius himself, who followed up his defeat in Judaea with a vigorous campaign under Bacchides that destroyed Judas’s army and left its famous leader dead on the battlefield (161/0).201 For a while, at least, Hasmonean hopes lay shattered by the unpredictable exercise of Seleucid force majeure. The Jewish nationalists were in disarray, the “sons of the Akra” triumphant.

Bacchides, taking advantage of his victory, spent a year fortifying and garrisoning strategic towns, including Jericho and Emmaus, throughout Judaea. He also took a number of Jewish hostages, who were held in custody on the Akra.202 Alkimos, now Judas was dead, had no trouble in entering the Temple sanctuary, where he ordered certain structural alterations, including the demolition of the wall of the inner court. Less than a year later he too died (159), apparently of a stroke, and zealots claimed that God had struck him down for laying blasphemous hands on the holy stones.203 Demetrius, by now too well aware of the irreconcilable conflicts inherent in the High Priest’s office, solved the problem by making no appointment at all.204 The office remained vacant until 152, when it was renewed as one item in the competitive bribery between Demetrius and Alexander Balas (above, p. 445). The lucky recipient was Judas’s brother Jonathan, whose roving guerilla bands had, since 160, defied all efforts by the Seleucid government to dislodge them, and virtually established an alternative, country-based, government to the increasingly unpopular Hellenizing junta in Jerusalem. For the protagonists in this new Syrian dynastic power struggle, the support of the Maccabees—despite their nationalist aspirations—was well worth having. Demetrius lavished military privileges on Jonathan; but Alexander Balas countered, as we have seen (above, p. 445), with the high priesthood.205 By now it should by clear enough why it was Balas’s offer that Jonathan accepted.206

The Hasmonean dream was moving toward its final fulfillment. Demetrius, in desperation, offered Jonathan every inducement he could think of, including the surrender of the Akra and the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s city walls at Seleucid expense.207 Jonathan shrewdly refused, figuring that if Demetrius lost to Balas his promises were useless, and if he won he would forget he had ever made them. When Balas in 150 defeated and slew Demetrius (above, p. 445), Jonathan was officially confirmed by the new king as civil and military governor of Judaea.208 When Demetrius’s son, Demetrius II, in turn replaced Balas as king (145; cf. p. 446), Jonathan, with cool effrontery, not only laid siege to the Akra, but then asked Demetrius for three provinces of Samaria and general tax exemption as the price for lifting the blockade. Demetrius II, a weaker man than some of his ancestors, and with problems of his own to solve, paid up.209 Jonathan subsequently switched sides to support Diodotus Tryphon and Balas’s son, Antiochus (below, p. 534), a move that in the end cost him his life as the result of Tryphon’s treachery.210 At an assembly in Jerusalem Jonathan’s brother Simon—the last surviving son of Mattathias—was elected to succeed him as national leader.211

Tryphon’s betrayal made a rapprochement with Demetrius II inevitable, and Simon was determined to exploit this alliance for all it was worth. The moment was propitious. Demetrius had to face not only Tryphon, but also a Parthian invasion of Babylonia (p. 533). Simon, with shrewd timing, petitioned him for exemption, in perpetuity, from all future tribute: in other words, for Judaea’s independence. The petition was granted, and an alliance made (spring 142).212 Nothing was said about the Akra; here Simon simply went ahead, enforced a blockade, and starved the Syrian garrison into surrender (June 141),213 calculating, correctly, that Demetrius would be in no position to do anything about a fait accompli. He also conquered Gazara and secured the port of Joppa.214 Then, in September 140, by unanimous vote of the Jewish priests, elders, and leaders in assembly, Simon was confirmed not only as military commander and ethnarch, but also as hereditary High Priest of Israel.215

So the Hasmonean family at last came into its inheritance, and fulfilled its long-standing ambition by succeeding to the defunct priestly house of Onias. The eulogistic paean to Simon in 1 Maccabees suggests the grounds for his popularity: he extended and safeguarded the frontiers, so that farming and herding could continue in peace (“Old men sat in the streets, all of them talking about the good times”); he fortified the cities, guaranteed the food supply, enforced the Torah, brought justice to the humble—“Everyone sat under his own vine and fig tree, and there was no one to terrify them. No one was left in the country to make war against them, and the kings were crushed in those days.”216 Propaganda perhaps; but one senses the very real relief that Simon undoubtedly brought to his war-torn people. It is worth recalling that in the two and a half centuries between Alexander’s death and Pompey’s capture of Jerusalem, more than two hundred campaigns were fought in or across Palestine.217 For nearly a century—apart from one brief Seleucid resurgence (below, pp. 535–36)—Mattathias’s line enjoyed absolute rule. It was not until 63 (below, p. 658), with the final Seleucid collapse, that the Romans, despite their senatus consultum of alliance with the new princely temple-state,218 wrote finis to this dynasty, as they had done, and would do, to so many others.