One of the more tempting excuses for Rome’s progressively more radical, steadily less reluctant policy of intervention and eventual takeover in the eastern Mediterranean was, beyond any doubt, the patent inability of the rulers in situ to manage their own affairs. This not only encouraged what Rome, and conservatives generally, saw as dangerous sociopolitical trends—mass movements by the dispossessed, encroachment by non-Mediterranean tribal elements—but, worse, proved disastrous for trade, a fault that Roman administrative paternalism could seldom resist the temptation to correct. In addition to the rampant scourge of piracy—for which, as we have seen (above, p. 557), Roman policy itself was at least in part responsible—a general condition of acute economic and, intermittently, political anarchy now afflicted both Syria and Egypt. Cities, local chieftains, and individuals all broke away when they could from a now highly inefficient (though no less captious and oppressive) system of central bureaucracy. Endless internecine dynastic conflicts, combined with relentless extortion (to pay for these and other excesses), had all but destroyed the countryside.

Since both Syria and Egypt were potentially the most fertile and productive areas imaginable, this represented a more than usually monumental feat of short-sighted stupidity—and indeed one is constantly amazed at just how much, even in extremis, could still be extracted from the inhabitants to meet yet another crisis. Alexandria, of course, had the advantage, in addition, of still-substantial royal treasures. In 59 Ptolemy XII Auletes raised almost six thousand talents,1 perhaps a year’s revenue, perhaps less, to bribe Caesar, now consul, into successfully upholding his claim to recognition by the Senate,2 which thus showed itself prepared, once again, to forget the terms of Ptolemy X’s will (above, p. 553). Though some of this money was raised through a loan, or loans, from the Roman banker Gaius Rabirius Postumus,3 the rest came from Ptolemy’s own resources, while the loans were recouped by extorting extra funds from his long-suffering subjects. His annual revenues, indeed, were variously estimated at between six and twelve and a half thousand talents.4 Even so, the Egyptian chōra was in a desperate state. Too many peasants had either been sold off into slavery, or else driven by despair to quit their holdings and join the ubiquitous bands of brigand mercenaries that had come, together with the pirates,5 to form a virtual tiers état, an unacknowledged countersociety preying on the system it had abandoned.

This was a situation that positively invited Rome’s attention. Unfortunately, as we have seen, the profit principle proved no less irresistible to Roman administrators, businessmen, and, all too soon, senators than it had done to the Macedonians. The tradition, after all, was well established. It had been what panhellenism was all about, as early as the fourth century: a united ethnic crusade against the East, with wealth and power as its objectives, cultural superiority (and Xerxes’ long-past invasion) as its justification. That had been the whole moral basis of Alexander’s expedition, of the sharing of the spoils by his successors. Material greed and racial contempt had been the fuel that maintained Macedonians in power, from the Nile to the Euphrates, for three centuries—while their own mores steadily degenerated, and, more subtly, were infiltrated by the culture of those whose capital they stole, whose languages they ignored. Now, with the Romans—whom Alexander’s descendants, prematurely, also dismissed as mere barbarians (above, p. 318)—the situation was abruptly reversed: it was Rome that very soon began to display contempt for these effete and fractious dynasts.

Examples abound. We recall the circle that an impatient commissioner drew in the dust round Antiochus Epiphanes on the Day of Eleusis (above, p. 431), or the way in which Scipio Aemilianus led the unwieldy Ptolemy Physcon, at a cracking pace, on foot, through the streets of Alexandria (above, p. 539). For indecision or excess a well-brought-up Roman had nothing but contempt. When Ptolemy XII Auletes, en route for Rome, visited Cato of Utica in Rhodes, after being driven out of Alexandria (59/8)—his six-thousand-talent bribe might have bought him Rome’s recognition, but the extortions employed to pay it off did not endear him to his subjects6—Cato, who had a touch of the coarse Cynic about him to offset his Stoicism, received his visitor while suffering from acute dysentery, and lectured him, in vain, on the disadvantages of dealing with Rome’s corrupt leaders.7 Had the Romans brought to Asia a reasonable moderation to temper their administrative efficiency, they would have been welcomed everywhere with open arms. Unhappily, the basic attitude of almost every Republican proconsul or praetor was precisely that of his Macedonian predecessors: here was an unbelievably rich Oriental milch cow, to be squeezed for all it would yield, a handy source for paying off campaign debts or funding grandiose Campanian building projects. The principle of exploitative foreign domination was upheld: the Romans, as should by now be clear, simply organized the extraction with greater ruthlessness and finesse.

The provincials did not fail to take note of the fate (in this case a rigged trial and exile) that befell an administrator, like Rutilius Rufus, who tried to give them equitable treatment.8 The inevitable result was Mithridates’ massacre of Roman and Italian citizens, followed by a major uprising. Yet the lesson was not learned even then. In 68 the effective political destruction of Lucullus,9 despite his formidable successes against Mithridates (below, p. 656), showed just what lay in store for any Roman consul or general, however well placed, who incurred the wrath of the tax farmers and negotiatores by showing himself too lenient (in their view) toward provincials. It took Octavian’s cool and long-term cynicism to realize that better results could be obtained by clipping the herd rather than fleecing it, and his immense auctoritas to deal with the financiers effectively. With the empire came some sort of equity, provincial justice, and sensible capital investment. Under the dying Republic it was, rather, a case of one corrupt foreign administration stepping in to replace another when it destroyed itself.

Behind the last convulsive struggles of Seleucids and Ptolemies Roman policy—or, worse, free enterprise minus a policy—can always be sensed in the background. Worse still, from the viewpoint of the Greeks in particular, was the imposition of rival foreign warlords—Caesar and Pompey, Octavian and Antony—who not only fought out their own dynastic struggles on Greek soil and in Greek waters, but bled the inhabitants white for supplies, from grain to warships, and had an unnerving habit of executing those who chose the wrong (i.e., the unsuccessful) side. Roman egotism was matched, as so often, by Greek cynicism: survival became the prime objective, and Cavafy catches the mood to perfection in a poem about the news of Actium, a naval battle that Octavian (against Greek hopes and expectations) won, reaching Asia Minor. A local official, responsible for the organization of an honorific decree lauding the victor, reflects: “But there’s no need for us to draft a new text. / Only the name needs changing.”10 The “parody of a Caesar,” the “ruinous” figure from whom Greece has been rescued, is now, like one of those mass-produced statues with interchangeable heads (above, p. 574), ANTONIOS rather than, as originally planned, OKTABIOS: the same number of letters, a snug fit for a stoichēdon inscription, with its crosswordlike regularity of horizontal and vertical spacings.

If Ptolemy Auletes—the self-styled Theos Philopatōr Philadelphos Neos Dionysos, but known in Alexandria, more accurately on several counts, as “the Bastard” (above, p. 554)—enjoyed a relatively undisturbed reign of almost thirty years (80–59/8, 55–51) in which to indulge his passion for flute playing (Aulētēs means “Piper”) and other, less mentionable, habits, that was no tribute to his strength of character.11 “He was not a man,” says Athenaeus, contemptuously, “but a flute blower, a trickster.”12 On an inscription from the temple of Isis at Philae one of the king’s Greek votaries proudly describes himself as “Tryphon, Catamite of the Young Dionysus”:13 he was perhaps a member of one of those Dionysiac guilds of actors and musicians that supported the Ptolemaic ruler cult.14 There were, in fact, two good reasons why Ptolemy Auletes, and his kingdom, survived as long as they did. To begin with, he had no serious rivals for the throne. This did not mean he was popular—far from it—but it did set his enemies a problem when it came to replacing him. At the time of his enforced exile in 59/8, while this new socius atque amicus populi Romani, based, with his retinue, on Pompey’s Alban estate, was shopping round Rome for further political backing (and, more important, for further massive loans to service his existing debts), the Alexandrians—who had thrown him out, in the first instance, partly for his tame acquiescence in Rome’s absorption of Cyprus (below, p. 652), partly on account of the extortionate way he went about recouping the bribes he had disbursed,15 and in general showed remarkable unanimity in their opposition to his Roman subservience16—scraped the very bottom of the dynastic barrel trying to find any acceptable substitute for him.17

After a little-known son of Cleopatra Selene had died on them during negotiations, and a grandson of Antiochus VIII Grypos had been vetoed by Aulus Gabinius, Pompey’s henchman and now governor of Syria (who was by this time in receipt of bribes from Auletes), in desperation they picked on an alleged royal claimant whose chief title to consideration was the name of Seleucus.18 His appearance, and oafish manners, got him the nickname in Alexandria of Kybiosaktēs, “the Salt-Fish Hawker.” The ulterior purpose of this frantic search was to find a male consort for Auletes’ daughter Berenice, who had been proclaimed queen in her father’s absence, perhaps at first as a temporary measure. The evidence is patchy, and in places contradictory,19 but sense can be—indeed, has been20—made of it. Auletes left behind, as co-regents in his absence, his wife (and sister) Cleopatra V Tryphaena, together with their eldest daughter, Berenice IV.21 Two other daughters, Arsinoë and Cleopatra VII, the future queen, were barely adolescent, while the boys, Ptolemy XIII and Ptolemy XIV, were still infants. Cleopatra Tryphaena’s regency was terminated after about a year, in 57, by her death. At this point it was considered vital that Berenice IV, now sole regent, should marry, and Seleucus Kybiosaktes was picked, faute de mieux, as consort. Berenice and her backers were now clearly aiming at permanent usurpation.

After a few days of marital intimacy, however, Berenice came to the conclusion that there were some humiliations not even political ambition could sweeten, and had her new husband strangled. To replace him en secondes noces she chose one Archelaus, who claimed Mithridates as his father (and had been making overtures to Aulus Gabinius on that basis), but was in fact the son of Sulla’s old opponent of that name (above, p. 563). A little plebeian blood, it might be thought, would not come amiss in the Ptolemaic pedigree. Not that this alliance did her much good either: in due course her father, Auletes, having laid out the vast sum often thousand talents for that privilege,22 was brought back to Egypt, in anything but a loving paternal mood. Aulus Gabinius—hand in glove with the king’s backers, led by Rabirius Postumus (see below)—invaded Egypt, defeated Archelaus’s lackluster army, and, on Pompey’s advice, returned Auletes to his throne (55), where one of the restored monarch’s first acts, predictably enough, was to execute the overambitious Berenice.23 Gabinius’s cavalry commander during this expedition was the young Mark Antony,24 who (as at least one ancient source, almost inevitably, alleges)25 found himself much attracted by another of the king’s daughters, the fourteen-year-old Cleopatra, now left, in terms of age, as next in line for the throne. Nothing came of this attraction at the time, if it ever existed: Cleopatra always went for top people, and Antony still had his way to make.

Despite his spendthrift ways and dissolute character, Auletes, once restored, held on to the throne of Egypt until his death. Cyrenaica had been finally taken over by Rome in 74 (above, p. 551); Cyprus, too, as we have seen, in 58 became part of the province of Cilicia,26 so that Ptolemy was now left with Egypt alone as his fief—a situation that his daughter Cleopatra, in due course, would go to great lengths to reverse. Even here, however, he was encumbered by maladministration and bad debts. As a desperate measure, and under heavy pressure from Gabinius, he invited his main Roman creditor, the banker Gaius Rabirius Postumus, to become his finance minister (dioikētēs). Better, from Rome’s viewpoint, to let the local bureaucracy collect what was owing, under Roman supervision, than turn the country over to the doubtful mercies of an overindependent tax-gathering consortium.27 The financial activities of Rabirius are graphically described by Cicero in a speech for his defense: we hear of his wide-ranging contracts, his involvement in state enterprises, his provincial investments and vast foreign loans, to governments and kings.28 We know such men well: today their credit is similarly overextended abroad, and they suffer very similar embarrassments in consequence.

Rabirius, though a little unhappy (like many Romans of his sort, he was thoroughly xenophobic) at the thought of abandoning his toga and going Greek, nevertheless saw this appointment as a godsend. He had an enormous amount at stake, and what better way was there to enforce the payment of the king’s debt, with interest, than to preside over the royal exchequer?29 In other words, as dioikētēs he would be using the available Ptolemaic system to guarantee Roman interests. He set about this task with such uncommon dedication that before a year was out he had to leave Egypt in a hurry (54/3): Ptolemy’s “imprisonment” of him—a restriction from which he seems to have escaped without trouble—was in fact almost certainly a protective measure designed to shield this exploitative Roman dioikētēs from the fury of the Alexandrians. Rabirius’s enemies in Rome prosecuted him for accepting tainted money from Gabinius; Cicero made the speech in his defense.30 The case was abandoned on a technicality. Aulus Gabinius himself had not been so lucky. His restoration of Ptolemy and his alienation of the publicani (again, it was suggested, through lenience to the provincials)31 exposed him to no less than three prosecutions, for treason, bribery and extortion, and corrupt practices, respectively. The first charge—for having left his province to conduct a campaign in Egypt—ended in an acquittal, and the third was dropped; but they nailed him on the second (extortion in his province, taking bribes from Ptolemy). Cicero spoke for the defense, even though he had, shortly before, described the treason acquittal as an “impurity law,” and indeed had assured his brother that he would never touch the case.32 Despite his efforts Gabinius was found guilty, and fined ten thousand talents: by no coincidence, the precise sum that Ptolemy was said to have disbursed. This meant, in effect, a sentence of exile.

Behind this flurry of litigation in Rome we glimpse the jealous infighting of rival magnates, of Populares and Optimates; and herein, of course, lay the second reason for Ptolemy’s long survival. The idea of annexing Egypt had been in the air for some time, at least since Scipio Aemilianus and his mission had come to spy out the country’s resources (140/39: above, p. 539). Ptolemy X Alexander’s will bequeathing Egypt to Rome of course added a new dimension to this proposition (above, p. 553). Crassus, as censor, spoke out strongly in favor of annexation (65).33 It is no accident that the will, and the political exploitation surrounding it, first surface in a speech of Cicero’s, the De Lege Agraria, delivered two years later, during his consulship. There were, in fact, powerful objections to annexation. A strong proconsul in Egypt, to begin with, would have an almost perfect launching pad to supreme power: all political groups in Rome were anxious, and with good reason, to keep their opponents from securing such a plum. A second, perhaps even more cogent reason was the lack of that independent municipal self-government essential to mediate between Rome and the royal fiscal bureaucracy.34 No senatorial proconsul could find his way through that maze; far better to retain the monarchy, which at least could operate its own system, and then collect from the top. Thus a weak Ptolemaic ruler was the perfect compromise solution, and the Flute Player survived until his natural death in 51 through the mutual suspicions, hostilities, and calculations of his ambitious Roman patrons. No accident that when Egypt was finally, and inevitably, annexed, Augustus—in this like any Ptolemy before him—kept the country as his personal fief, entrusted it only to prefects of equestrian rank, created a professional Roman bureaucracy to administer it, and would not let a senator so much as set foot on its soil without personal authorization.

While Ptolemaic Egypt ran down slowly on borrowed time, Seleucid Syria—and Asia Minor generally—foundered in a series of almost nonstop wars. The treaty of Dardanus, imposed by Sulla on Mithridates in 85,35 proved singularly ineffectual: it was verbal only, it lacked ratification by the Senate, and it lost all effective force with Sulla’s death (78).36 Mithridates, in fact, had received no more than a temporary setback. He had never surrendered all Cappadocia to Ariobarzanes, and as early as 83 was busy preparing a large expeditionary force to recover the Greek settlements of the Cimmerian Bosporus. On the excuse that this force constituted a threat to Rome, Sulla’s governor Licinius Murena, ignoring the treaty, went to war again, and got beaten for his pains. Mithridates found this an excellent opportunity (since he could complain, justifiably, of bad faith) to expel all Roman garrisons from Cappadocia.37 He also showed alarming signs of once more offering a focal point for all anti-Roman rebels and counterculturalists. He offered slaves their freedom, he was hand in glove with the Cilician pirates,38 and—worst of all—in 76 or 75, seeing that another confrontation with Rome was inevitable, he made a deal with the Roman rebel general Sertorius in Spain. The political impact of this move was on a par with Philip V’s Carthaginian treaty in 215 (above, p. 297).

Mithridates offered Sertorius forty ships and three thousand talents, a very sizable subvention; in return he got a military mission to reorganize his own army along Roman lines.39 In the expectation that Sertorius would, ultimately, win his war and then, like Sulla, impose his will on Rome, Mithridates sought recognition from him of Pontic rule in Asia Minor. Sertorius, ever anxious to publicize his own Republican bona fides, rebel or no, conceded Mithridates’ right to occupy Cappadocia and Bithynia, “nations ruled by kings and of no concern to the Romans,”40 but roundly condemned any attempt to recover the province of Asia, which was, he asserted, legitimately Rome’s.41 Mithridates’ final objective, it seems clear, was Roman recognition for an Anatolian empire that would, in effect, replace the crumbling Seleucid regime.42

The support of Sertorius was probably the decisive factor that led, almost immediately, to another Mithridatic war against Rome.43 This time the king of Pontus, stung by senatorial bad faith, and seeing clearly that there were many more ambitious men like Murena, only too eager to renew a, hopefully, profitable war, took the initiative in 74 by invading Bithynia, possibly already annexed as a Roman province.44 It is a mark of what he was up against that the situation, on the face of it, was a good deal less encouraging than it had been in 89/8. There were, for instance, no less than four legions now stationed in Asia Minor: a regular army of occupation. On the other hand Mithridates had strengthened his navy, was reorganizing his army along Roman lines, could count on the Cilician pirates as firm allies,45 and had already scored a more than psychological success by his defeat of Murena. The Romans, too, were obliged to deal with Sertorius in Spain, and this reduced the forces they could spare for an eastern campaign. But Mithridates was taking no chances. He spent the summer and winter of 74/3 making energetic preparations for war —felling timber, building more ships, manufacturing arms, stockpiling grain, and conducting a vigorous recruiting campaign.46 He was, as Velleius justly observed, “the last, bar the Parthians, of the autonomous kings,”47 independent, no puppet of Rome—and meant to stay that way.

When Rome mobilized, late in 74, both consuls—Lucius Licinius Lucullus and Marcus Aurelius Cotta—were commissioned to defend the East, a remarkable compliment to Mithridates’ reputation: neither Philip V nor Perseus had rated this peculiar mark of respect.48 Cotta, a breathtakingly incompetent political appointee,49 was to take the fleet to Bithynia (which he did, and promptly lost it); Lucullus, with all his invaluable experience as Sulla’s lieutenant, would have command of the legions in Asia and Cilicia—a force, be it noted, less than one-quarter the size of his opponent’s—and go in pursuit of Mithridates (spring 73).50 It is interesting, and significant, that Cilicia was envisaged as the likeliest theater of operations, since this was where the pirates conducted their business, and they, too, were very much in the Senate’s mind during 74. It was now that a special maritime command, an imperium infinitum, was set up to enable a competent commander to tackle the problem of Mediterranean piracy without being restricted to any one province.51

The problem had indeed become critical.52 As early as the time of Diodotus Tryphon in the mid-second century (above, p. 557),53 rival rulers and rebels had encouraged the organization of piracy on a hitherto-unprecedented scale.54 The most profitable attraction for these corsairs, as Strabo makes clear,55 was the slave trade, in which the pirates for a long while got considerable covert support from Roman businessmen.56 But it was the backing of various governments, above all that of Mithridates, that really encouraged what has been well described as “the biggest growth-industry and protection-racket in the ancient world.”57 It was the growing success of the enterprise that finally turned even Roman slave dealers against it: the legitimate trade of the entire Mediterranean was being crippled. Piracy ruled the seas from Sicily to Crete,58 from Crete to the Cilician coast.59 The straits between Crete and the southern Peloponnese yielded such rich booty that the pirates referred to this stretch of water as the Golden Sea. Corsairs now ventured ashore, attacked towns and fortresses, raided temples and shrines for their valuables, even sailed into the harbor at Ostia, the port of Rome, burning and pillaging:60 to such an extent did they disrupt commerce that the grain supply to the capital was seriously threatened.61 Coastal areas round Brundisium and in Etruria were regularly raided: well-connected women travelers, even two praetors, despite their official insignia, had been carried off.62

But there was another, more socially threatening, side to the pirates’ activities. They now operated with over a thousand large ships, “scorned the title of corsairs,” and “likened themselves to kings, tyrants, great armies, believing that if they united, they would be invincible.”63 They are reported to have been among the first to practice Mithraism, as a secret and binding cult. They also took particular pleasure in viciously mocking Roman power and authority when a captive of rank fell into their hands.64 Once again the lure of the alternative society can be glimpsed in this cut-throat world of rapine and revolt: not for the last time, antipopulist rhetoric about piracy and brigandage hints at a violent, desperate, but unacknowledged social conflict.65 It was this combination of economic disruption and political radicalism that now made firm action by Rome inevitable. Short-term profiteers who had made their fortune through dealing with the pirates now were the first to demand protection against the hideous specter they had raised. There had been previous reprisals against the pirates: by Marcus Antonius in 102/1 (above, p. 557),66 and, more recently, by Publius Servilius Vatia between 79 and 75.67 Though more or less successful at the time, these efforts had done nothing to eradicate the plague on a permanent basis: like pitchforked Nature, the pirates always returned.

Now, at least, the problem rated an imperium infinitum, probably with proconsular authority—dangerous power for one man, though as Vellcius cynically remarked, concern was considerably modified by the recipient, and intrigue in Rome guaranteed that competence was the one quality the first holder of the command lacked.68 Marcus Antonius was presumably appointed in 74 because he was his father’s son, and his father had dealt with the pirates a quarter of a century earlier (see above); but this talent was clearly not hereditary. What Antonius did understand, however—not surprisingly in the circumstances—was extortion: indeed, he got a reputation for causing worse depredations than the pirates themselves.69 On the other hand, when he tried to settle accounts with the Cretans at sea, he suffered a humiliating defeat: many of his ships were cut off, and their occupants (including his quaestor) were strung up from their own yardarms in the chains they had brought with them.70 Antonius had no option but to patch up a humiliating peace with the pirates (71):71 his title, “Creticus,” seems to have been bestowed on him as a kind of derisive joke, and he died soon afterwards.72 Curiously, his main claim to fame is the fact that he was the father of Mark Antony, a very different character. When he returned to Rome, the Senate, perhaps emboldened by the recent death of Sertorius (72) and Crassus’s savage annihilation of the great slave revolt led by Spartacus (71)—social revolution was now everywhere in retreat—decided to ignore his reluctant treaty. Instead, they sent out to Crete a strong, efficient, and brutal commander, Quintus Caecilius Metellus, who not only “laid waste the whole island with fire and sword,”73 but subsequently, when the Cretans, their cities now besieged by his land forces, attempted to surrender to Pompey (see below), flatly refused to acknowledge Pompey’s maius imperium, thus precipitating an unpleasant diplomatic incident.74 He, too, though for rather different reasons, “got nothing out of his striking victory apart from the title Creticus”:75 at this stage Pompey was riding very high. Even so, the quarrel had come within appreciable distance of escalating into “a minor civil war.”76

Despite Metellus’s depredations, the pirates generally were bolder than ever; and now they once more had Mithridates in the field to support them. His initial successes caused great alarm, and with good reason, in Rome. That Asia Minor was not lost to the Romans at this point was entirely due to the efforts of that extraordinary individual Lucullus, an often scandalously underrated soldier and statesman,77 who in three short years (73–70) raised the siege of Cyzicus, pursued Mithridates through Bithynia into Pontus, rescued his wretched colleague Cotta (who had been blockaded in Chalcedon and lost sixty-four ships there), raised a new fleet with which he regained supremacy at sea, took Mithridates’ capital cities of Sinope and Amaseia; then shook the brief Armenian empire of Tigranes to pieces (69/8), and, in short, did all the hard fighting for which Pompey, a year or two later, got the credit, besides making an equitable financial settlement in Asia—something, as we have seen (above, p. 649), that was his ultimate undoing.78 Plutarch gives a graphic, and unpleasantly plausible, account of the outrageous abuses by Roman publicani and moneylenders that Lucullus summarily terminated.79 Sulla’s indemnity of 20,000 talents had already been paid off twice over; yet (like a modern house mortgage) the total, by the accruing of interest, had been brought up to the staggering figure of 120,000 talents, so that cities, no less than individuals, were desperately in debt, with public property mortgaged to the hilt,80 and many free citizens reduced to serf status. Lucullus cut the annual interest rate to 12 percent maximum, abolished all interest in excess of the principal, set a ceiling of one-fourth of any debtor’s income on the amount payable to a creditor, and penalized any moneylender who added interest to principal by mulcting him of the entire sum due. As a result, all debts were paid off, and all liens and mortgages canceled, within four years. But, hardly less important, Lucullus acquired a group of deadly and implacable enemies in Rome. Since the financial lobby, as a matter of policy, had lent large sums, on nominal security, to many of the leading politicians, it could always count on raising a powerful pressure group at need, operating, more often than not, through venal tribunes of the people.

Lucullus’s veterans—probably with encouragement and disinformation from interested parties—came near to mutinying: it is true that his discipline was tough, but it had been singularly effective, and in the ordinary course of events it takes more than strictness in the field to rouse experienced troops against so fair and successful a commander. They grumbled at inaction, at not pursuing Mithridates à outrance; but the canny Lucullus knew better than to let himself be lured into a disastrous wild-goose chase among the remote mountains of eastern Anatolia. In Pontus he would stay: let Mithridates commit himself. This strategy did not make Lucullus popular; and meanwhile his powers were being skillfully cut from under him in Rome. Pompey (who knew how to get on with the business community) obtained a special command to clean up the mess. The Lex Gabinia of 67 invested him with sweeping powers; Lucullus was eased out of office and left to enjoy a leisured, luxurious retirement, a wealthy Epicurean whose pleasures were by no means all philosophical, an intellectual bon vivant and man of action whose most lasting legacy to Italy and the West was the Pontic cherry tree.81 Pompey proceeded to steal his glory—Lucullus got a grudging triumph, for which he had to wait till 63, but small thanks otherwise82—and made a showy end to the work that his predecessor had all but completed.

First, however, he had to deal with the pirates. Under the piracy law proposed by Aulus Gabinius, a consular—carefully left unnamed—would be given a three-year imperium, covering the entire Mediterranean, with the right to levy troops and to raise funds (the latter not only from the Roman treasury, but also from officials abroad). He would have a fleet of two hundred fighting vessels, and be entitled to appoint fifteen legati at praetorian level. His authority would cover all islands, and extend fifty miles inland.83 After violent senatorial opposition (but with the help of Caesar and his friends) the bill was finally passed, and a further law was then tacked on, appointing Pompey to the command, and increasing the forces at his disposal: five hundred ships, 120,000 infantry, five thousand cavalry, twenty-four legati instead of the original fifteen, with a couple of quaestors thrown in.84 With this vast, indeed excessive, force at his disposal, Pompey divided the Mediterranean into thirteen separate subcommands, with a legatus in charge of each.85 The aim was to sweep the seas in an easterly direction, thus reopening Rome’s supply lines from Sicily, Sardinia, and North Africa as quickly as possible. In a mere forty days this task had been accomplished, and the pirates were forced to regroup along the Cilician coast.86 Even now Pompey still faced such implacable opposition in Rome as necessitated his return to the capital in mid-campaign.87 But on his return to Cilicia he wound up the operation with speed and vigor. Every ruler in Asia Minor was obliged to supply troops or cash for the war effort.88 Within three months (rather than the three years envisaged by his commission) Pompey had stormed the pirates’ last stronghold, and the campaign was over.89 The menace of piracy, despite some flattering claims to the contrary,90 had not been entirely eradicated; nothing, granted the social conditions of the age, could do that. But it had been dealt a crippling blow.

Pompey had, it must be admitted, done a brilliant job; but there does seem to have been something suspiciously easy about it. Between the pirate leaders and the Roman imperator backed by the publicani (and, thus, violently opposed, even at the height of his success, by conservatives such as Piso, who sneered at him as a “new Romulus”)91 some kind of deal could well have been worked out in advance: Pompey’s agents were everywhere long before his official arrival. There is a most uncharacteristic lenience in the treatment of these defeated sea rovers (who, among their other crimes, had sheltered runaway slaves, kidnapped high Roman officials, and fought for Mithridates): not only a mass amnesty, but something very like an environmental rehabilitation program. Normally a captured pirate could expect the worst, as Cicero, not a vindictive man by nature, emphasizes with some relish.92 Pompey’s prisoners, on the other hand, were treated as victims of circumstance, which indeed most of them were; they were encouraged to take up farming, and settled in abandoned cities on the Cilician plain and elsewhere.93 Virgil’s old bee-keeper in the Georgics, it has been suggested, was one such resettled corsair.94 It does seem as though Pompey had perceived, and attempted to deal with, some of the grim endemic problems that lay behind the social scourge of piracy; at least he had the common sense to realize that out-of-work pirates needed an alternative way of making a living.

Nothing, of course, succeeds like success, and in 66 Pompey was given—by the Lex Manilia, and with the support, this time, of bieu-pensants such as Cicero and Servilius Vatia as well as that of Caesar and the financiers95—an extended command to deal with those two elderly bogeys, Mithridates and Tigranes, both of whom had already had the heart knocked out of them by Lucullus.96 Adding insult to injury, Pompey met Lucullus and stripped him of his troops, calling him a Xerxes in a toga; Lucullus, with waspish venom, retorted that Pompey was a vulture, never killing its own prey, but always feasting on the carrion that other beasts had killed.97 Pompey then, insisting on unconditional surrender in order to avoid an overeasy victory,98 drove Mithridates back through Cappadocia and Pontus, shut all doors of retreat on him, and forced his lukewarm son-in-law Tigranes (who was left his throne, but little else) to deny him even his indirect support. Finally, in 63, the old Pontic lion chose death rather than keep up his now-hopeless struggle, getting a Gaulish officer to dispatch him when he found himself immune to even the strongest poisons, embarrassed, at the last, by his lifelong instinct for self-preservation.99

Meanwhile, in the late summer of 64, Pompey had moved down into Syria. Here, at Antioch, he was confronted, perhaps to his surprise, with the pathetic figure of Antiochus XIII Asiaticus (above, p. 553), still hopefully chasing that will-o’-the-wisp, the Seleucid crown, just as a decade earlier he had gone to Rome to seek the throne of Egypt. He had, indeed, already had a heady taste of glory. When Tigranes evacuated Syria in 69, the Antiochenes had hailed Antiochus XIII as their rightful king.100 Lucullus approved the appointment, and Antiochus was duly crowned as the heir of the Seleucids.101 Since then another claimant, his third cousin Philip II, had appeared. They had the backing (indeed, were the creatures) of two powerful rival Arab emirs.102 When Pompey scornfully turned down Antiochus’s plea for confirmation, with the scathing comment that the man who had yielded Syria to Tigranes was not likely to save it from Arabs and Jews103—indeed, he might have added, was only too likely to make a present of it to his Arab patron —Antiochus had no option but to go back to that patron, Sampsiceramus (Shemashgeram). The Arab, not being a man to throw good money after bad, lost no time in murdering him. If Philip II was, in fact, that grandson of Antiochus VIII Grypos whom Aulus Gabinius refused to allow into Egypt (56/5: above, p. 650), he survived a little longer, but after 63 we hear no more of his claims to kingship.104

So, ingloriously and amid greater issues, died the last obscure claimants to the empire that Seleucus Nicator had founded, which at its apogee had stretched east to the Land of the Five Rivers, westward as far as the Hellespont, and south to the very gates of Egypt. Much ink has been spilled on the problem of just why Pompey reversed Lucullus s policy and abolished the Seleucid dynasty: to have a Roman bastion against the Parthians, to police Syria properly, to prevent the revival of piracy, or simply because any decision of Lucullus’s was better reversed (the theory of inevitable imperial expansion scarcely merits discussion). The true answer is surely simpler and more pragmatic: Pompey did away with the Seleucids because they were now too weak to be any conceivable use to Rome as a client kingdom, and through their weakness would be a continual focal point for instability and insurrection.105 The time had come for tidy, effective government, the imposition of the pax Romana: indeed, it is arguable that Pompey had regarded Syria as Roman property ever since the surrender of Tigranes in 69.106 This kind of arrangement was something that Pompey understood and in which he believed: vain, venal, and pliable in his political dealings, he was a first-class administrator of the Roman status quo.

His settlement of the East is not strictly relevant to this story in detail, but one or two general observations on it may be worth making.107 First, it was unique in being, for the first time, executed by one man with supreme powers, on the spot, and responsible to no senatorial commission. Thus it paved the way for the very similar authority late exercised by Augustus. Second, it was immensely profitable, on a scale not seen since Alexander handed out largesse after his Eastern conquests.108 The client-kings, for instance, paid tribute, and this line item formed a substantial element from now on in the imperial budget.109 More graphically put, in terms of personal wealth Pompey “could have bought Crassus out without feeling the pinch”—and Crassus was the man who said that no one could call himself rich unless he was in a position to support a legion out of income.110 Large loans, to cities or individuals, ensured political subservience. Pompey came home a multimillionaire, almost literally holding the gorgeous East in fee. Third, his settlement reinforced the tradition of imperial foreign government that, as we have seen, was the mainstay of the Successors. With a fine-tuned sense of relative xenophobia, Rome henceforth administered the civilized, that is, Hellenized, areas of the oikoumenē directly, while turning over the nonassimilated fringe to the mercies of client-kings with grotesque non-Mediterranean names. Pompey observed that he had found Asia a frontier province, but left it at the heart of the empire;111 beyond the new provinces of Pontus and Bithynia, Syria and Cilicia, there now lay a whole string of dependent kingdoms—Colchis, Paphlagonia, Commagene, Judaea, Armenia, among others.

Finally, after learning one or two lessons the hard way, Roman administrators were, for some centuries, to make a success of the job—something their Greek or Macedonian predecessors had never quite got the hang of. The laissez-faire excesses of the publicani were brought into line, local leaders were tempted with the offer of Roman honors and appointments. Nothing had changed in principle; the Romans—with that coarse psychological pragmatism that was at once their curse and their greatest blessing—simply made the system work. In 60 B.C. Diodorus Siculus saw a Roman lynched in Egypt for killing a cat;112 Romans were no less contemptuous of foreign ways by Juvenal’s day, over half a century later,113 but at least they had learned better tact and public manners. The disastrous bellicosity and even more disastrous greed of a governor such as Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus showed himself in Macedonia (57–56) became less common as time went on:114 in other words, Roman imperialism depended for its effectiveness on its officials’ sense of law and decorum. It is a tribute to Roman mores that this foundation proved as strong as it did; but ultimately it became exposed to the same weaknesses as had assailed the Ptolemies and Seleucids. It is, as we are often reminded, no answer to the problem of slavery to be consistently kind to one’s slaves.

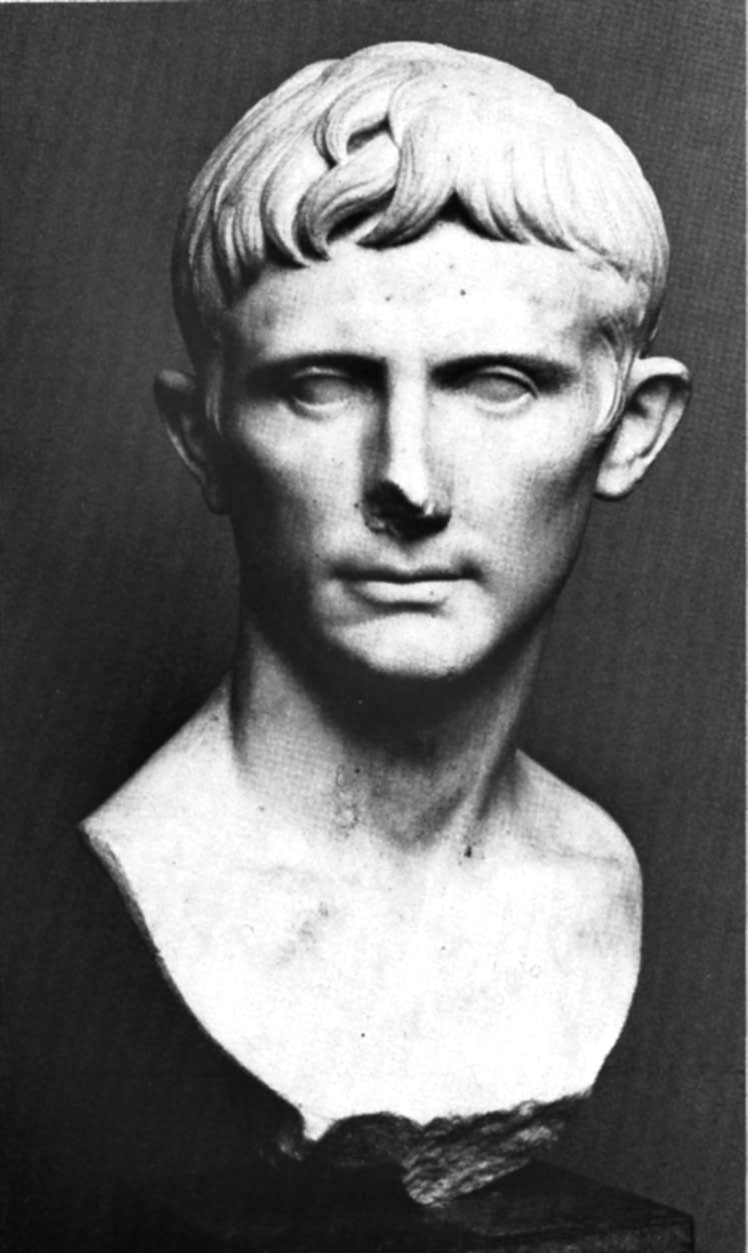

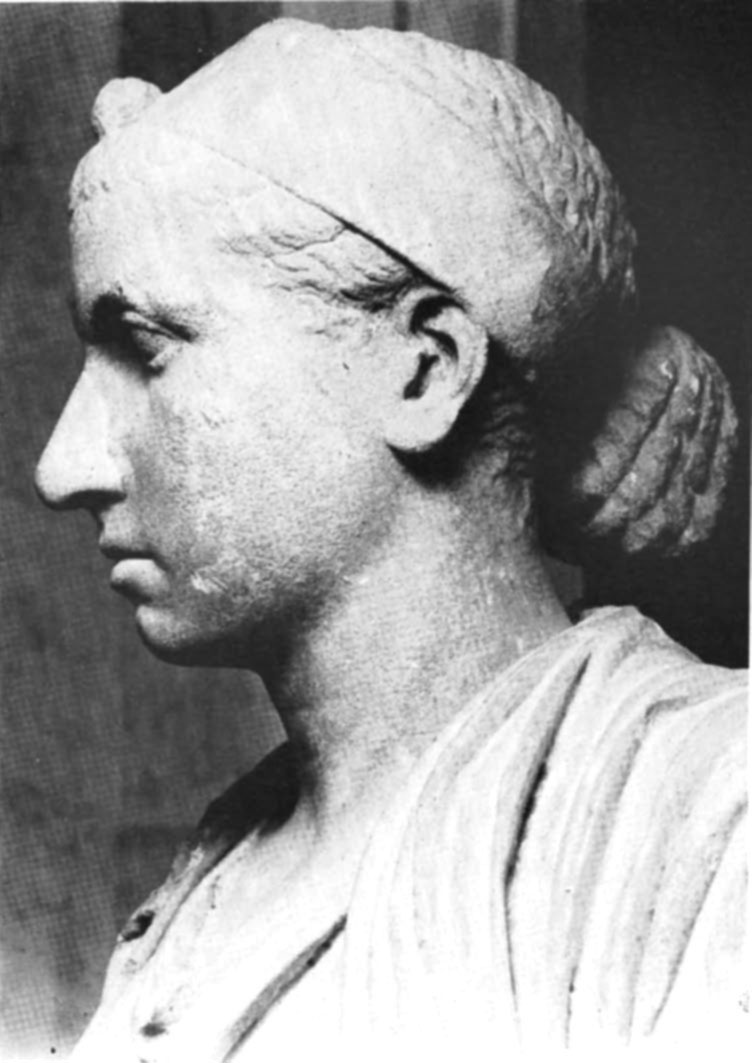

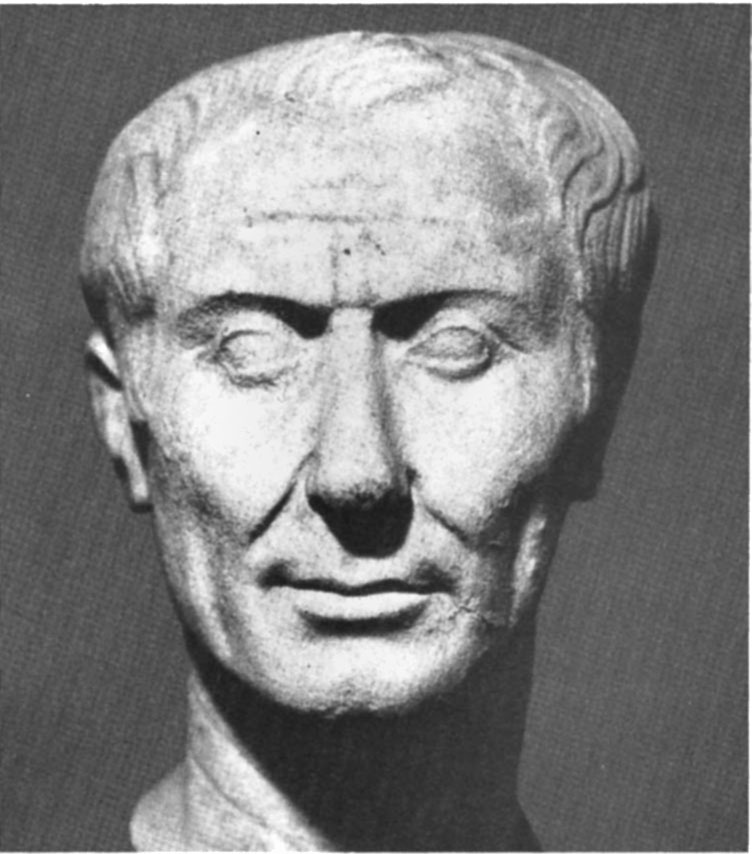

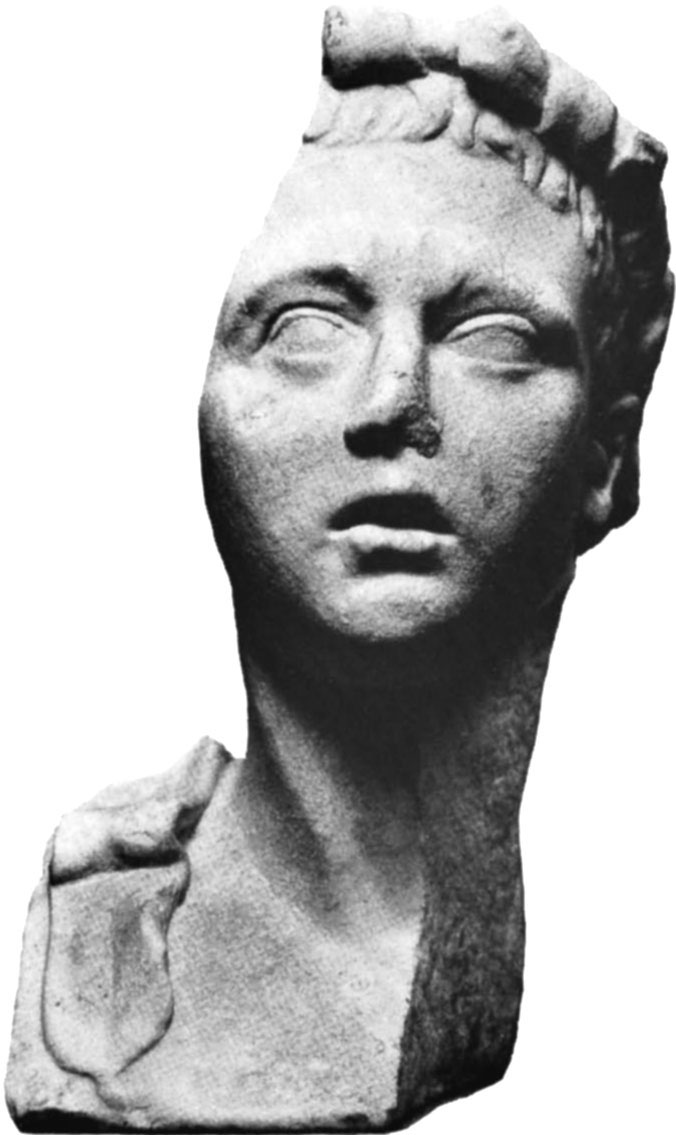

If the Seleucids fizzled obscurely, the Ptolemies went out in a blaze of glory that has inspired great poetry down the ages. In the spring of 51 Ptolemy Auletes died, leaving the kingdom in his will, jointly, to his eighteen-year-old daughter Cleopatra, and her younger brother Ptolemy XIII, then about twelve.115 In Cleopatra the tradition of brilliant, strong-willed Macedonian queens reached its apotheosis. With Cyprus, Coele-Syria, and Cyrenaica gone, with the world her ancestors had known crumbling about her, with famine at home and anarchy abroad, this astonishing woman not only dreamed of greater world empire than Alexander had known, but came within an iota of winning it. Tarn, with romantic hyperbole, claimed that Rome had feared two people only, Hannibal and Cleopatra.116 That is to be taken in by the propaganda mills presenting her as an Oriental ogre, a drunken hypnotic Circe of all the passions, to distract Roman attention from the fact that what Octavian was really fighting was a desperate civil war against his own former comrade. But no one could fail to take her seriously. How far her sexual allure was exercised for its own sake, and how far in pursuit of power, we shall never know for certain. But there are one or two pointers. Like many Hellenistic queens, she was passionate, but never promiscuous. Caesar and Antony apart, we hear of no other lovers, and a prurient tradition could hardly have failed to commemorate them had they existed.117 The wretched surviving iconography—a far from flattering series of coin portraits, the uncertainly ascribed Cherchell bust118—suggests neither a raving beauty nor a voluptuary. Pascal’s remark about the world being changed if Cleopatra’s nose had been shorter is singularly unfortunate,119 since if her portraits show her as she was, it could hardly have been longer.120 She appears to have inherited this physiognomy from her father, Auletes.121 There is also her choice of lovers to consider. Anyone who so consistently aimed for the top is unlikely to have been motivated by nothing apart from sheer unbridled passion.

The irresistible conclusion is that if Pompey rather than Caesar had come calling in Alexandria after the battle of Pharsalus in 48, the result would have been precisely the same: Pompey was no less conceited than Caesar, and at least as ambitious. Indeed, when in 49 Pompey’s son came to Alexandria looking for men and ships and cash, it was suggested that he may have obtained the queen’s favors as well, as a gesture of good will and support.122 If we can believe our sources (and they are all, for this period, heavily, and inevitably, tinged with propaganda or corrective hindsight, or both), Cleopatra even, at the age of thirty-nine, with Antony’s corpse scarcely cold, made a desperate pass at the young Octavian after Actium.123 On her record it could well be true; and whatever that record suggests, it is not nymphomania. The contrast between her handling of Caesar and the way she treated Antony is also highly instructive. In neither case, Shakespeare notwithstanding, does the evidence suggest a grande passion. What it does indicate is that while Cleopatra—brilliant, quick-witted, fluent in nine languages (which did not, interestingly, include Latin),124 a mathematician and shrewd businesswoman125—had a genuine respect and admiration for Caesar, Antony’s emotional vacillations, intellectual shallowness, and coarse excesses nearly drove her insane. She had to deal with Antony, so she made the best of him; but we do not hear of her laying on those endless stupefying entertainments for the abstemious Caesar, whose wit and brilliance matched her own. To Caesar she was delivered at night, by a Sicilian merchant, concealed in a carpet or bedroll, a through-the-enemy-lines joke that he appreciated, as she well knew he would;126 it was for Antony that she devised that vast and overornate parade down the river Cydnus to Tarsus, immortalized by Shakespeare and thus not always seen for what it was: a vulgar bait to catch a vulgar man, a conscious parody of those processions that earlier Ptolemaic monarchs had laid on for the delectation of the Alexandrian mob, and as a self-promoting gimmick abroad (above, pp. 158 ff.).127 She fought for her country, and her country—the Egyptian chōra rather than Alexandria —responded by offering to rise for her when all was lost, and treating her as a still-living legend for years after she was dead. She spoke Egyptian; she was the New Isis;128 from the very beginning of her reign she participated in Egyptian religious festivals; her portraits and hieratic cartouches adorned the temples of the old gods.129 She was, in short, a charismatic personality of the first order, a born leader and vaultingly ambitious monarch, who deserved a better fate than suicide with that louche lump of a self-indulgent Roman, with his bull neck, Herculean vulgarities, and fits of mindless introspection.130

The times, however, were hard, and she was forced to make of them what she could—which was a great deal. The civil wars in Italy broke out in 49, two years after she came to the throne. She made her independent spirit clear from the start. By August 51 she had already dropped her young brother’s name from official documents, despite traditional Ptolemaic insistence on titular male precedence among co-rulers.131 (Throughout her reign, independent or not, Cleopatra was always forced to accept either a brother or a son, however underage or otherwise ineffectual, as obligatory consort: there were some traditions not even she could ignore.) She also, exceptionally, put her own portrait and name on her coinage, again ignoring those of her brother. This, not surprisingly, alarmed the more powerful court officials in Alexandria. Moreover, when her Gabinian mercenaries killed the Roman governor of Syria’s sons, who had come to require their presence to help their father against the Parthians, she at once, on her own initiative, sent the ringleaders to Syria in chains.132 Such behavior very soon brought opposition to a head. Certainly by 48, and in all likelihood two years earlier, a palace cabal, led by Theodotus, the eunuch Pothinus, and a half-Greek general, Achillas, ousted Cleopatra in favor of her more pliable younger brother, with themselves as a council of regency.133

Between 51 and 49 Egypt was also suffering from drought, inadequate Nile floods, and the inevitable consequence: bad harvests and famine. A royal decree of 27 October 50—with Ptolemy XIII’s name on it—banned the shipping of grain to any destination except Alexandria. It has been plausibly argued that Cleopatra had already been driven out, probably to the Thebaid, and that the decree sought, inter alia, to deprive her and her supporters of supplies.134 In any case she soon set about raising an army among the Arab tribes east of Pelusium, much as Cleopatra IV had done in not-dissimilar circumstances (above, p. 549). At some point she and her sister Arsinoë moved to Syria,135 and it seems likely that they went there from Upper Egypt, returning subsequently by way of Ascalon—which may have temporarily served as Cleopatra’s base136—and the eastern marches of Egypt beyond Pelusium.137

Meanwhile Pompey, defeated at Pharsalus (Aug. 48), took ship for Alexandria. He was relying, unwisely, on his position as backer, indeed as Senate-appointed guardian, of young Ptolemy XIII;138 the Egyptian alliance, as we have seen, had sent him men and ships. He seems not to have realized, till it was too late, just how far Pharsalus had destroyed his international reputation and credit. Achillas and his fellow regents were already working out their best approach to Caesar; in their eyes Pompey was nothing but a dangerous embarrassment. They had him murdered as he stepped ashore (28 Sept. 48), an object lesson for the precocious boy king, who watched this scene from the dockside, arrayed in his diadem and purple robes. Pompey’s severed head was pickled, and afterwards presented, as an earnest of good will, to his conqueror, who at least had the grace to shed tears at the sight.139 Caesar may have been only too glad to have Pompey thus providentially put out of the way, but the circumstances of his death were appalling, and Caesar himself knew this better than anyone. At the same time the episode encouraged him in what was to prove a near-fatal Egyptian adventure.140 When he came ashore himself at Alexandria four days later (2 Oct.), he was in a mood of careless and arrogant confidence, with an escort of no more than thirty-two hundred legionaries and eight hundred cavalry. His public reception was anything but ecstatic: he had been accompanied ashore by twelve lictors carrying the fasces, a clear hint of his intentions. Riots followed.141

Ptolemy XIII was away at Pelusium, ready to defend the frontier against his elder sister.142 Caesar coolly installed himself in the royal palace and began issuing orders. Pothinus the eunuch, determined not to meet the Roman’s exorbitant financial and other demands (including the discharge of vast debts still owing to Rabirius Postumus, which Caesar, for his own purposes, had underwritten),143 brought Ptolemy back to court, but took no steps to disband his army. At this point Cleopatra, anxious not to be left out of any deal being cut, had herself smuggled through these hostile lines, like contraband, and turned up in her carpet. Both she and her brother were invited to appear before Caesar’s ad hoc judgment seat the following morning; but by then Caesar, who was instantly captivated by Cleopatra’s insistent charms, had already made her his lover, as she doubtless intended he should.144 Young Ptolemy instantly grasped the situation (hardly difficult, in the circumstances), and rushed out in a fury, screaming that he had been betrayed, to rouse the Alexandrian mob.145 The general belief, fomented by Pothinus, that Caesar indeed planned to make Cleopatra sole ruler, as a puppet of Rome, had generated a highly inflammatory mood in the city. Ptolemy, however, was quickly brought back by Caesar’s guards, while Caesar himself went out and made a conciliatory speech. Highhandedness had perforce, for a while at least, to be abandoned.

The danger of Caesar’s position was such that he provisionally recognized the two co-regents’ younger brother and sister, Ptolemy XIV and Arsinoë, as joint rulers of Cyprus,146 even though Cyprus had been officially annexed by Rome a decade before (above, p. 650), and exploited with vigor by Caesar’s future assassin Brutus (above, p. 555), who did very well out of loans on which he charged 48 percent annual interest.147 (Once Caesar got back in control of the situation, however, he rapidly reneged on this concession; Arsinoë, to her great annoyance, far from descending on Cyprus en grande dame, was kept under virtual house arrest in the royal palace, a decision with embarrassing consequences, as we shall see.)148 There followed a series of lavish Alexandrian parties. But Pothinus had not played his last card: in November he summoned Ptolemy XIII’s veterans from Pelusium, and Caesar suddenly found himself blockaded in Alexandria by an army twenty thousand strong.149

The so-called Alexandrian War, which followed, though in many ways pure opéra bouffe, came as near to destroying Caesar himself, let alone his reputation, as any campaign, military or political, that he ever fought. Once he had to swim from the mole to save his life, leaving his purple general’s cloak behind as a trophy for the enemy (Feb. 47).150 The warehouses and some part of the great Alexandrian Library went up in flames.151 Caesar managed to capture the Pharos lighthouse (above, p. 158), which safeguarded his control of the harbor.152 Arsinoë, meanwhile, contrived to escape from the palace, fled to Achillas, and was promptly proclaimed queen by the army and the Macedonian mob, an act for which her sister never forgave her.153 All through that winter fighting and intrigue sputtered on. Arsinoë’s eunuch, Ganymede, murdered Achillas; Caesar meanwhile executed Pothinus. In February 47, at some cost to himself, he extended his control to Pharos Island and the Heptastadion mole (this was the occasion on which he lost his cloak), and also turned Ptolemy XIII over to the Egyptian opposition as a good-will gesture, probably in the covert hope of stirring up trouble between his advisers and those of Arsinoë.154 In any case, Caesar’s intelligence officers reported that relief was at hand. At the eleventh hour he and his beleaguered legionaries were rescued by a mixed force under Mithridates of pergamon (26 Mar. 47).155 Ptolemy XIII fled and was drowned in the Nile.156 Thus Cleopatra, whom Caesar had restored, officially, to joint occupancy of the throne of Egypt, now, in effect, indeed became sole ruler—although as a sop to tradition she was duly married off to her younger brother Ptolemy XIV, now aged eleven.

Caesar is more likely to have got himself into his dangerous and demeaning scrape out of careless arrogance and a determination to lay hands on Egypt’s still-vast accumulated resources rather than through a simple infatuation for Egypt’s queen. At the same time the personal advantages of this stylish and intelligent young lady, not to mention those of the system she had inherited, were clearly not lost on him. For one thing, he had lost no time in getting her pregnant, a move that we can safely attribute to dynastic policy, not mere carelessness. Rather than make Egypt a province, with all the senatorial intrigue and rivalry that this was bound to entail, Caesar had every intention of shoring up the Ptolemaic regime, on his own terms. To have a son in line for the throne would by no means come amiss, whatever the status of consort and heir in Rome. Meanwhile, to placate the Alexandrians and the Egyptian priesthood, Cleopatra obligingly wed her sibling co-regent, while her younger sister, Arsinoë, languished under arrest with a charge of high treason pending against her. By way of compensation for all she had been through, Caesar now took his ripening inamorata on a prolonged pleasure trip up the Nile,157 and only left to attend to more pressing business in Syria a few weeks before the birth of her, and his, son Ptolemy Caesar, known as Caesarion, on 23 June 47.158

In July 46, after his successful African campaign, Caesar returned to Rome, to be showered with unprecedented honors, including four successive triumphs and a ten-year dictatorship. During these celebrations (Sept.–Oct.) he brought over Cleopatra and her entourage, establishing them in his own town house, a return of hospitality that caused considerable offense among conservative Republicans, and was not made easier by the queen’s de haut en bas social manners.159 By then he was mulling over ideas about deification and world empire that seemed, or were thought, to include the establishment of Alexandria as a second capital, and of Cleopatra herself as some kind of bigamous queen-goddess,160 the New Isis, as she styled herself Rome buzzed with gossip. Everyone, whatever they said about her in private, paid visits to Cleopatra in Caesar’s villa across the Tiber—even Cicero, whom she snubbed, and who professed to find her both odious and arrogant.161 Her underage brother-cum-husband also accompanied her: it was all very un-Roman.162 Perhaps on her insistence, her sister Arsinoë, chained, was led in Caesar’s triumph (46), to the evident disgust of the crowd. Caesar, always alert to public opinion, released Arsinoë,163 whose ambition—as one might expect in a Ptolemaic princess—was no whit dampened by the experience. Cleopatra herself lived in luxurious style, with a huge retinue. Caesar erected a golden statue of her in the temple of Venus Genetrix (where else?), and claimed paternity of Caesarion, something Republicans found alarming, since it suggested that he planned to marry Cleopatra, despite the laws against bigamy and unions with foreigners.164 On the other hand, they could thank the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes—basing himself on the work of Callippus in the fourth century (above, p. 460)—for Caesar’s introduction of a rational solar calendar, a welcome reformation, since the civic year had got no less than three months ahead of the solar one.165 His irrigation schemes and establishment of public libraries also betray obvious Alexandrian influence: the Egyptian interlude had clearly not been a total waste of time.

But the Ides of March 44 put an end to all these grandiose dreams. Two weeks after Caesar’s assassination, when the will was known and Caesarion, inevitably, had no place in it, Cleopatra, with more speed than dignity, and perhaps in real danger of her life, left Rome and returned to Alexandria. “The queen’s flight does not worry me,” Cicero wrote to Atticus, with relish.166 On her arrival Cleopatra lost no time in having her sibling consort, Ptolemy XIV, assassinated, and Caesarion established, at the tender age of four, as her new co-regent.167 She found Egypt suffering from both famine and plague, due in part to the neglect of the Nile canals during her absence: inundations were still low, and bad harvests continued from 43 until 41, with consequent social unrest.168 The last thing Cleopatra needed at this stage was another palace revolution. While civil war raged between Caesarians and Republicans, she secured recognition for Caesarion from Caesar’s former lieutenant Dolabella by sending him the four legions Caesar had left in Egypt:169 this also provided her with a good excuse to get them out of the country. They were, in any case, captured or taken over by Cassius, and Dolabella committed suicide at Laodicea (summer 43).170 She stalled demands by Cassius himself for ships by pleading impoverishment through famine and plague,171 but was, clearly, acting on behalf of the Caesarian cause. After Dolabella’s defeat and death, only a violent storm prevented her from joining Antony and Octavian with a large fleet.172

In 44 Antony, during his brief period of supreme power, had set up Arsinoë as ruler of Cyprus (thus implementing Caesar’s unfulfilled promise),173 and also, in all likelihood, as a potential counterweight to Cleopatra: at this stage he still believed in hedging his bets. During the fraught years that followed, Cleopatra seems to have regained Cyprus from her sister, who fled to Ephesus (43?).174 In any case, after the two battles of Philippi (42), which saw the deaths of Brutus and Cassius, and the triumvirs Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus triumphant, it became quite clear to Cleopatra with whom she would have to deal. Octavian went back to Italy so ill that his life was despaired of Antony was the man to watch. Meanwhile she got an unexpected bonus: on 1 January 42 Caesar’s official divinization was announced in Rome, and though its main object was the promotion of Octavian, who now proclaimed himself “Son of Divine Julius” on his coins, a deified father—even on the wrong side of the blanket—would not come amiss for Caesarion, either,175 not least since the triumvirs, in recognition of her aid to Dolabella, had granted her son the right to the title of king.176

By the time that Antony summoned her to that fateful meeting at Tarsus, in 41, she already knew more than enough about him: his limited tactical and strategic abilities, his great popularity with his troops; his blue blood, which was so embarrassingly offset by financial impoverishment; the drinking, the philoprogenitive womanizing, the superficial philhellenism, the Herculean vulgarity, the physical exuberance and brutal ambition, the Dionysiac pretensions to godhead.177 Rural Egypt might be on the verge of economic collapse, but the queen—who had still further debased Auletes’ already poor silver coinage, cutting the proportion of actual silver from 33 to 25 percent178—put on a show that Ptolemy Philadelphos could not have outdone:179 the gilded poop, the silver oars, the purple sails, the Erotes fanning her, the Nereid handmaids steering and reefing. All this made an immense impression at the time, and (via North’s Plutarch) provided Shakespeare with one of his most famous bravura descriptive passages.

Antony was tickled by the idea of having a blue-blooded Ptolemy (his previous mistresses, not to mention his present wife, Fulvia, a powerful termagant, all seem to have been shrewishly middle-class),180 and by the coarse implications of all this royal finery: eight or nine years later we find him writing to Octavian, asking him why he has changed so much, turned so hostile—“Is it because I get into the queen?”181 He spent the winter of 41/0 with Cleopatra in Alexandria, emphasizing his private status on arrival: Caesar’s gaffe had not been lost on him. Our sources outdo each other in proclaiming his subservience to the queen, the life of dissolute luxury they led together.182 One hears the grinding, ex post facto, of Augustan axes here. Cleopatra, they insist, could get whatever she wanted out of him—including the execution of Arsinoë (never forgiven for her brief fling as titular queen in 48–47) who, for obvious reasons, now fancied the Republican cause. Now it is quite true that Antony executed Arsinoë in 41;183 but this was done at least as much out of political calculation as in a state of besotted subservience to a lover. Tarsus, too, had been the scene of “a good deal of unromantic negotiation.”184 Arsinoë had revealed herself as an ambitious and unscrupulous enemy: the volatile Alexandrians had already recognized her claim to the throne once, and might well do so again. Antony’s decision to eliminate her needs no other explanation. What was more, he showed himself equally firm with Cleopatra herself at this stage. The evidence suggests that Cyprus was removed from her control: despite all the romantic publicity surrounding her first encounter with Antony, he seems to have been a good deal less pliable than propaganda would suggest.185 Indeed, to some extent it may well have been Cleopatra who was exploited. The triumviral finances badly needed reinforcement, and Cleopatra could be generous enough in the pursuit of her own ends. Like Caesar, Antony found Egypt full of attractions, not all of them sexual or antiquarian. Logistics, too, played their part.

Both Cleopatra and Antony, then, had highly practical ulterior reasons for cultivating one another; how much personal chemistry helped the equation is hard to tell. Nor can anyone be certain how soon Antony planned to return when he left Cleopatra in the early spring of 40, or what he told her—not necessarily the same thing. Her magnetism was by no means irresistible, since in the event he did not see her for another four years. His wife, Fulvia, who had become involved in a serious breakaway movement against Octavian over land allotments for veterans, fled to Greece, where, after a bitter confrontation with Antony, she fell ill and died—a fortuitous accident that, again, did Cleopatra less immediate good than she had hoped or expected.186 Public considerations once more came first. That same autumn Antony made his peace with Octavian at Brundisium (Brindisi), cemented the alliance by marrying his fellow triumvir’s sister, Octavia—a beautiful and high-minded young intellectual, recently widowed, and with three children from her first marriage, to Gaius Claudius Marcellus—and became officially responsible for the East.187 The civil wars at last seemed at an end; this was the period in which Virgil, during the pregnancies of Octavia and Octavian’s wife, Scribonia, wrote his famous, and famously ambiguous, fourth Eclogue, prophesying the approach of a new Golden Age with the birth of an (unnamed) child—a gift, later, for Christian propagandists. Meanwhile in Alexandria Cleopatra, never one to do things by halves, bore Antony twins, a boy and a girl. His first child by Octavia, a girl, was born in 38.

Just what Antony thought he was doing at this point is not wholly clear. He may have been playing the Roman card; he may have thought he could finesse Cleopatra against Octavia, in whose company, during the winter of 38–37, he played the dutiful intellectual in Athens, attending lectures and going the rounds of the philosophical schools. At all events, a fresh Parthian invasion of Syria, led by the Roman turncoat Labienus,188 kept his uneasy relationship with Octavian going until 37, when it took another meeting and treaty, signed at Tarentum (Taranto) and largely achieved through Octavia’s tireless personal diplomacy, to patch up the shaky alliance.189 Subsequent events suggest that Antony felt, from now on, that a power play was developing against him in Italy. This, of course, was true: at Tarentum, for instance, he had left two squadrons (120 vessels) of his fleet for Octavian to use against Sextus Pompeius’s quasi-piratical forces in Sicily, against a promise of four legions that, for one reason or another, failed to materialize, an omission that may well have tipped the scales in his final choice between Octavia and Cleopatra.190 Octavian’s growing enmity also must have turned him back toward the idea of playing winner-take-all, with Alexandria as his base. If Octavia had borne him a son, things might have been different; but she had not, and Cleopatra had. Cleopatra also held the still-impressive accumulated treasure of the Ptolemies, something that Octavian, too, kept very much in mind, and with good reason: when he finally laid hands on it, and this became known in Rome, the standard interest rate at once fell from 12 to 4 percent.191

So Antony left Italy and went east, with the Senate’s authority to reallocate client kingdoms—a commission that, as we shall see, he proceeded to interpret in a more than liberal fashion—and to deal with the Parthians. By now his mind must have been made up. Octavia, whose second child by him—another daughter—had just been born, accompanied him as far as Corcyra, apparently in a poor state of health; Antony then sent her back home, on the excuse, prima facie reasonable enough, that he was about to embark on the Parthian campaign, and did not want to have her exposed to the rigors and dangers that a life in the field would entail. Besides, she would be of more use to him in Rome, keeping the peace with her unpredictable brother and looking after her five children.192 All plausible enough; and yet the first thing that Antony did, on reaching Antioch, was to send for Cleopatra. After their long separation it was now that his, or their, schemes for what Will calls a “Romano-Hellenistic Orient” began to take shape.193

Antony proceeded to lavish on the queen not only Cyprus, which he had so unceremoniously removed from her control at Tarsus in 41, but also the cedar-clad Cilician coast, so ideal for shipbuilding, not to mention Phoenicia, Coele-Syria, and the richest spice-bearing regions of Judaea and Arabia, dispositions that not unnaturally caused vast offense in Rome,194 and not only because of Cleopatra’s personal unpopularity there: these provincial areas were in fact not in his authority to dispose of, and the obvious purpose of their allocation to Cleopatra, Egypt itself being virtually without timber, was to provide lumber and shipyards for the creation of a large Egyptian fleet.195 The twin children were also now acknowledged by Antony, and officially named Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene, titles powerfully evocative of Hellenistic dynastic ambition.196 This is confirmed by the fact that Cleopatra now inaugurated a new era of her reign (37/6), probably to celebrate these new territorial acquisitions.197 Whatever ultimate plans Antony may have had, however, the plain fact of the matter was that he needed Cleopatra’s support for his forthcoming Parthian campaign. This proved a disastrous fiasco (36), and Antony in defeat became more obligated to Cleopatra than ever. She had just borne him a third child. Now she met him and his ragtag army, two-fifths of which had been lost, on their return to Syria, bringing food, clothing, and cash subsidies with her. In early 35 Antony returned with her to Egypt.198

Octavia, in Athens, also with supplies and reinforcements, wife and mistress in nurturing competition, received a curt letter from her husband forbidding her to come farther.199 Octavian had released no more than two thousand troops, together with seventy of Antony’s own ships: it is more than possible that he meant to provoke Antony into a showdown. The future Augustus could now invoke this calculated insult to his sister (whether sexually or politically motivated made little odds) when the need for a casus belli arose. War between him and Antony was now more or less inevitable. Even when Antony had the fugitive Sextus Pompeius executed,200 Octavian, while publicly congratulating him, also contrived to make capital out of the incident by contrasting it with his own lenient treatment of Marcus Lepidus, the ineffectual ex-triumvir whom he had allowed to retire into private life. Had Antony gone to Rome in 35 himself, he might have patched things up, both with Octaviwan and with his wife; but he did not, and it seems safe to assume that Cleopatra at this stage used all her influence to keep him in Alexandria. Octavia, whatever the truth concerning what Shakespeare called her “cold and holy disposition,” and despite Antony’s snubs and infidelities, remained unswervingly devoted to him through thick and thin, even looking after his children by Cleopatra when the queen was dead;201 this does not sound like a mere Roman sense of duty, and Cleopatra was surely well advised to keep Antony away from her at all costs.

So it came about that in 34 Antony committed himself still further to his independent Graeco-Roman dream. After a successful—and financially rewarding—Armenian campaign he celebrated a triumphal parade through Alexandria, playing the role of the New Dionysus, while Cleopatra, enthroned as the New Isis, presided over the ceremony.202 (Inevitably, when the news reached Rome, this occasion was misinterpreted as an unauthorized and improper Roman triumph.) Only a few days later a yet more explicit political ceremony took place.203 In the great Gymnasium of Alexandria, with Cleopatra once more robed as Isis, and Antony enthroned by her side, titles were bestowed upon the royal children. Ptolemy XV Caesar (Caesarion)—though carefully subordinated to the royal pair—was made joint ruler of Egypt with his mother and proclaimed King of Kings (she became Queen of Kings, a higher honor still). Alexander Helios, robed like an Achaemenid monarch, was declared Great King of what had been the Selcucid empire at its zenith, Parthia included. His sister, Cleopatra Selene, was instated as Queen of Cyrenaica and Crete. The youngest son of Antony and Cleopatra, Ptolemy Philadelphos—his name a deliberate evocation of past glories—was proclaimed, at the age of two, King of Syria and Asia Minor: he was also dressed in Macedonian royal robes.

Cavafy, in one of his most brilliant poems, “Alexandrian Kings,” comments: “The Alexandrians realized, to be sure, / That all this was mere words, theatricality.”204 True enough in the strict sense: the titles bestowed, like certain modern Catholic sees, did not correspond with political realities—(“What hollow words these kingdoms were! ”).205 Young Ptolemy Philadelphos had in effect been given the Parthian empire, while Cleopatra Selene “ruled” over a Roman province. However, as a program of intentions these so-called Donations of Alexandria were disquieting: they served clear notice of Antony’s far-reaching ambitions, as indeed did Cleopatra’s role as the New Isis, his as the New Dionysus; they also stressed the dynastic form that he had chosen to implement them.206 Though Roman generals in the East since before Pompey’s day had been making and unmaking client-kings,207 this situation was different. True, Antony sought senatorial approval for the Donations after the event; but he can hardly have believed that it was wholly through Octavian’s obstructionism that his request was refused.208 The Donations not only laid improper claim to territories that were either outside Rome’s control or, worse, already under Roman administration; they also made it only too clear that Cleopatra and the formidable resources of Egypt were backing Antony’s dreams. Once again the irresistible lure of world empire was in the air: the grim lessons of the past three centuries had been quickly forgotten.

Oracles foretold a coming of true harmony between East and West, between Greek and Roman, under Antony and Cleopatra’s biracial New Order.209 Coins issued in 34/3 to celebrate the Donations bore the legend Basilissa Cleopatra Thea Neōtera (“Queen Cleopatra, the Younger Goddess”), and were minted in Antioch, thus emphasizing the queen’s, and her consort’s, determination to amalgamate the Ptolemaic and Seleucid royal houses. In addition, the last three words of the inscription were superbly ambiguous, since they could also mean “the New Cleopatra Thea”—and in such a context what better model to adopt than the formidable queen who, a century before, had married three Seleucid kings, outlived them all, and issued coins stamped with her own title and portrait (cf. above, pp. 445, 541)?210 Ten years after Caesar’s assassination Cleopatra once again, as Bevan says, “saw herself within measurable distance of becoming Empress of the world.”211 Her favorite oath was now “As surely as I shall yet dispense justice on the Roman Capitol.”212

In 32/1 Antony formally divorced Octavia, thus forcing the West to recognize his relationship with Cleopatra; he had already, unprecedentedly, put the Egyptian queen’s head and name on his official Roman coinage, the silver denarii that enjoyed an enormously wide circulation throughout the eastern Mediterranean.213 These acts also terminated even the pretense of his Roman allegiance, and Octavian proceeded to publish those clauses in Antony’s will that reproduced the Donations of Alexandria, forcibly removing the will from the custody of the Vestal Virgins in order to do so.214 He then formally declared war on Cleopatra, and on her alone; no mention was made of Antony.215 The whipped-up hysterical xenophobia current in Rome at the time can be sensed from the (largely factitious) propaganda of such Augustan poets as Virgil and Propertius.216 Cleopatra was the drunken lascivious Oriental, worked over by her own house slaves (famulos inter femina trita suos), whoring after strange gods and foreign ways. Horace describes her brain as “soused in Mareotic booze,”217 while for Propertius her tongue had been “submerged by endless tippling,”218 and Strabo claims that Octavian “stopped Egypt from being abused with drunken violence.”219 Inevitably, she was also portrayed as an indiscriminately sensual harlot,220 a charge that, as we have seen, was almost certainly false, though she did (it was claimed) derive a “really sensuous pleasure” from literature.221

Antony became the target of more serious, and better founded, political accusations, for example that he had misused troops, acted without senatorial authorization, and given away territories that belonged to Rome,222 yet a serious statesman of Messalla’s caliber still thought it worthwhile to charge him with using a golden chamberpot in Alexandria, “an outrage at which even Cleopatra would have blenched,”223 and which certainly shocked the elder Pliny, who reports it, adding that for such an offense Antony “should have been proscribed—by Spartacus” (the context makes it clear that this was not an ironic joke, and in any case Pliny’s sense of humor was vestigial). The mixture of coarseness and sensibility in Roman mores is fascinating: one can never be certain just which improbable peccadillo will next call down the full force of some weighty gentleman’s rhetorical disapproval.224

The exaggerated charges against Cleopatra also reveal fear; and though today the outcome may seem inevitable—it is true that Antony’s Roman support had begun to crumble long before his actual defeat—at the time many must have believed that the New Isis would triumph, that Antony would indeed launch a dazzling new career of world conquest and imperial co-partnership from Alexandria. Dis aliter uisum: Jove and the future Augustus decided otherwise, and the dream of universal empire took a different form. Octavian’s crushing naval victory at Actium, on 2 September 31225—planned and won for him by his admiral Agrippa—finally put paid to Antony’s ambitions. Less than a year later, after a halfhearted defense of Alexandria against Octavian’s advancing army, Antony committed suicide. Cleopatra soon followed his example,226 perhaps with Octavian’s covert encouragement: if she was too proud to adorn a triumph in chains, like Arsinoë, her conqueror had not forgotten how the crowd warmed to that spirited captive. How much more sympathy, then, might not go out to his own adoptive father’s former lover? Better, as for Caesar after Pompey’s defeat, to be presented with a convenient, and dramatic, fait accompli. So Cleopatra’s prospective role in Octavian’s triumph was carefully explained to her, and she duly found her own solution—as her handmaid Charmian said, one fitting for a queen descended from so many kings.227 Once she was safely dead, admiring tributes to her noble end could be entertained without risk,228 while her heir Caesarion was butchered without compunction.229