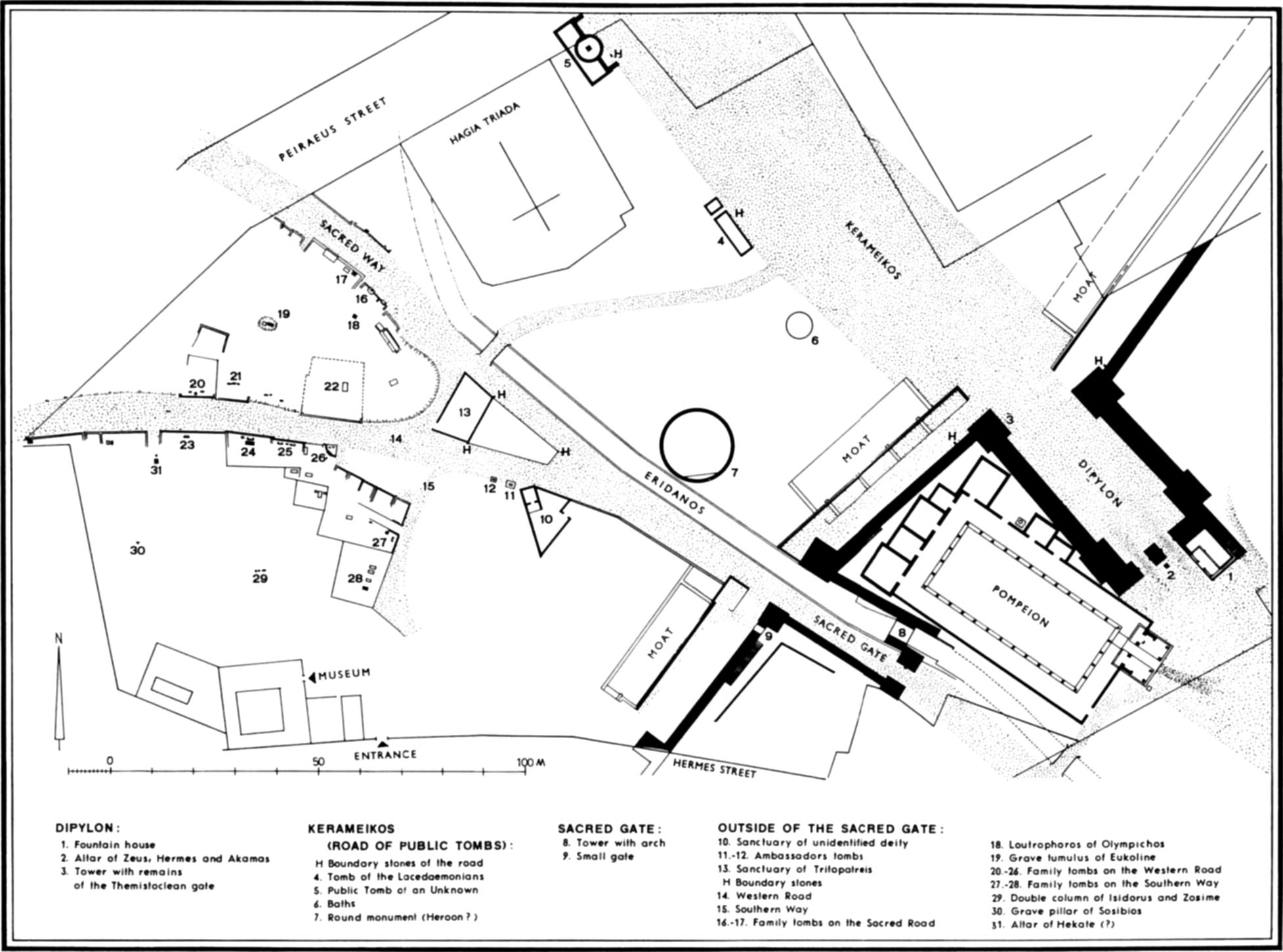

All societies, it has been said, get the philosophers and the architects they deserve, on the grounds that these tend to furnish a peculiarly accurate reflection of the Zeitgeist. Athens in the late fourth century B.C. is no exception to the rule. Her major buildings then were secular and commercial: Philo’s great arsenal in Piraeus (329), the Panathenaic theater and stadium, the large but unfinished peristyle on the northeast side of the Agora, probably designed to accommodate (in that ever-litigious city) an overflow of law courts. In the more traditional mode she patched and developed. A new temple of Apollo Patroös, on the site of the old sanctuary, was built during Lycurgus’s administration as public treasurer (337–325/4); he was also responsible for completing the extensive alterations carried out in the Theater of Dionysus, as well as the half-built Piraeus shipsheds, and for building the Lyceum’s gymnasium.1 Such activities, however, could hardly count as innovation.

In many ways the Athenian creative impulse—certainly the form of it that we associate with the Periclean era—seems to have run dry during this period. As early as 386 we find plays by the old masters—Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides—being performed at the great festivals along with less-regarded new productions; after 339 the same seems to have been true of Attic Old Comedy.2 Lycurgus also passed a law authorizing the erection of bronze statues to the three great fifth-century tragedians, and establishing a canonical text of their works (later purloined by the Ptolemies; see p. 89), from which actors were not permitted to deviate.3 When Aristotle, later in the fourth century, wanted to define the perfect tragedy, he went back a century, to the Oedipus Tyrannus.4 The mood was retrospective; there was a sense, instantly recognizable today, of being overwhelmed by one’s own classics. Though the architecture of the Agora was later to be transformed at least twice, it is noteworthy that neither of these changes would have taken place without external stimulus, in this case enlightened patronage by the wealthy, and quintessentially Hellenistic (i.e., nonclassical, non-Athenian), kings of Pergamon. “The Athenians were to create no more great buildings in their own manner and out of their own resources.”5 In literature, as we shall see, the mood had shifted, rapidly, from one of civic involvement to escapism, by way of fantasy, ivory-tower scholarship, and half-hearted social realism heavily laced with romance. The happy ending, by no coincidence, arrived in art about the same time that it seemed to be disappearing in real life. As we might expect, these trends are also faithfully mirrored in early Hellenistic thought.

It is often stated as a fact that Stoicism and Epicureanism were designed to support thinking men who had been disoriented by the collapse of the city-state, as a kind of “ring-wall against chaos.”6 This claim has to be scrutinized with some caution. The polis, it is argued, had “never given security,” whereas “Hellenism was a world of cities, and Hellenistic Greeks were making money, not worrying about their souls.”7 This is at best a half-truth. Though the polis may not have given security in the sense that a welfare state does, it did, until the end of independence, make each citizen in the assembly feel conscious of participation—full, practical participation—in the business of government. Aristophanes might make a joke of it, but Demos really did rule. The cities of the Hellenistic world, certainly those, like Athens, that had lost control of their own destinies, might keep up their ceremonies and traditions (the Athenian Panathenaic procession was still going strong under the Roman empire),8 but they had lost the special kind of confidence that only self-determination can produce.

The loss of external political freedom inevitably drove men inward on themselves. Not all were looking for the same thing, but a remarkable number of those who did not opt for financial, material success (and indeed, some who did) were on a quest for freedom of the soul. If they could not have true political eleutheria, at least they would achieve inner release, a mastery of the self. Now, this self-searching for the idea of spiritual liberation (endocosm, as it were, rather than exocosm) is the most noticeable feature that all Hellenistic systems of thought have in common. Just as earlier, in the archaic world of the eighth century B.C., Hesiod had had nothing to offset his impotence, when confronted with rapacious and unscrupulous local barons, apart from the force of moral principle,9 so now the loss of political autonomy impelled men to seek self-sufficiency (autarkeia). The disruption of old certainties, the subversion of traditional patterns and values, in particular those associated with the world of the polis, led to an obsession with Tyche—Chance, Fortune (see p. 400). Intellectuals who scoffed at anthropomorphic deities interfering with human affairs were (perhaps by way of compensation) hopelessly vulnerable to the random-numbers game, the unpredictable swerve (parenklisis, clinamen) in an atomized world.

In his treatise On Tyche Demetrius of Phaleron, reflecting on the eclipse of the Greek states by Macedon, and perhaps also on the vicissitudes of his own career, wrote: “Fortune does not correspond to our mode of life . . . and regularly demonstrates its power by confounding our expectations.”10 Virtue, in other words, was no guarantee of prosperity; Tyche (in this resembling any archaic Greek deity) was wholly indifferent to good works, much less good intentions. The Macedonians, Demetrius mused, had been given the prosperity previously enjoyed by the Persians, but only on loan. That was a shrewd assessment. Polybius, who lived to see the triumph of Rome, knew all about the mutability of Fortune: it took him as a hostage from his homeland and led him to make his life’s work writing, and explaining, the achievement of his conquerors (see pp. 269 ff.). Theophrastus was much criticized by intellectuals for endorsing Chaeremon’s claim that “Tyche, not reason, is what guides the affairs of mankind.”11 We will find the same sense of human impotence reflected in the plays of Menander (see p. 73). “Stop going on about intelligence,” says one character. “Human intelligence is that and nothing more. It’s Fortune’s intelligence that steers the world. . . . Human forethought is hot air, mere babble.”12

In his idiosyncratic monograph on Epicurus, the French scholar-priest Fr. A. J. Festugière wrote: “How was it possible not to realise that, from the day when the Greek city fell from the position of autonomous state to that of a simple municipality in a wider state, it lost its soul? It remained a home, a material background: it was no longer an ideal.”13 The migrants who drifted to Alexandria, to Antioch, to Pergamon or Ephesus, cut off from their roots, were alone, ciphers, like modern provincial newcomers to London or Paris or New York. Small wonder if their materialism took the logical step of deifying men on the basis of power and achievement. Ruler worship was to become one of the most characteristic phenomena of the Hellenistic period. When Demetrius the Besieger returned to Athens from Corcyra in 291 (see p. 127), he was greeted with a paean including the words:14

The other gods are far away,Or cannot hear,Or are nonexistent, or care nothing for us;But you are here, and visible to us,Not carved in wood or stone, but real,So to you we pray.

Those who had elevated Demetrius to the status of Savior God, the younger brother of Athena, could hardly do less than address him in these or similar terms; and the Parthenon then became his only logical habitat. Neither they nor modern critics should have been surprised at the consequences.

Nor was it an accident that Euhemerus of Messene, a philosopher-fabulist in Cassander’s circle (ca. 311–298), achieved such extraordinary popularity. In his best-known work Euhemerus described Panchaia, a utopia in the Indian Ocean, where the Olympian gods, it transpired, had been great kings and rulers deified by their grateful subjects.15 It would have been hard, at this time, to formulate a notion with greater epidemic appeal. Euhemerus became the Hellenistic equivalent of a bestseller: his work was one of the first Greek texts to be translated into Latin prose, and by none other than Ennius.16 Small wonder: it blurred the line between gods and human heroes; it could be used by intellectuals as ammunition to support atheism, or by propagandists at the royal courts to enhance the prestige of monarchy. If the common man, throughout the oikoumenē, the civilized Greek world, was to be subjected to autocratic rule, he might at least satisfy one side of his emotions by making a cult of it. Meanwhile he could pursue, in private, all those significantly negative virtues we find touted by Hellenistic philosophers: aponia, absence of pain; alypia, avoidance of grief; akataplēxia, absence of upset; ataraxia, undisturbedness; apragmosynē, detachment from mundane matters; apathia, non-suffering (or, freedom from emotion); and, positive for once, galēnismos, the tranquillity of a calm sea. Like Eliot’s women of Canterbury, they did not want anything to happen: their good, like Demetrius of Phaleron’s, was negative, predicated on the consistent avoidance of present troubles. Indeed, all of them except the Stoics made it a prime rule to avoid any kind of political involvement. The change from the values of the Periclean age, when those who contracted out were known, contemptuously, as the apragmones, the do-nothings, or the idiōtai, private people and, hence, idiots,17 is fundamental.

Yet the interesting thing is how far back before the onset of the Successor monarchies we find all these symptoms developing. They are not—this cannot be over-stressed—simply and solely the result of the loss of political autonomy. The cultivation of the individual soul was propounded in turn by Pythagoras, the Orphics, and Plato. Escapism meets us in many forms well before the end of the fifth century. Euripides’ choruses are always wishing themselves somewhere else, remote and romantic, preferably metamorphosed into birds. The ornithological motif reappears in Aristophanes’ comedy The Birds (414), where two disgruntled citizens want out of Athens, with its never-ending lawsuits and fiddling bureaucrats; Eupolis in The Demes (412), as we have seen, turned to dead leaders to solve Athenian problems.18 As early as Aristophanes’ Plutus (388) we find the assumption that wealth “is both the final cause and the prerequisite of all activities.”19

The world of the polis, in fact, was being attacked by intelligent moralists for its shortcomings long before it was rendered obsolete by external aggressors like Philip of Macedon. Demagoguery and mass hysteria were the populist vices, balanced by totalitarian violence on the part of oligarchical extremists, such as those intellectual aristocrats who in 411 spearheaded the revolution of the Four Hundred. If it was men like Critias, Plato’s uncle, who formed the Spartan-backed authoritarian junta of the Thirty, it was the free democracy that in 399, after several years of scarring civil war, was provoked into condemning Socrates. Plato himself reveals, in his Seventh Letter, how he became disillusioned with both forms of government.20 Relatives were eager for him to join the witch-hunting activities of the Thirty, and this shocked his sensibilities; yet how, on the other hand, could he accept, much less work with, a system that executed his philosophical master? Many responsible, intelligent men must have felt as he did; many must have shared his belief that the only solution was to jettison the old forms and concepts, to plan society anew. Hence, of course, the Republic. Hence, too, the Theory of Ideas, that striving to find eternal perfection and pattern somewhere behind the appalling flux of mundane appearances. Yet Plato was an aristocrat born and bred, and the brave new world he fashioned was itself, inevitably, a totalitarian and elitist utopia. Worse, his idealist theorizing proved itself a rather more subtle version of the prevalent escapist mood. When put to the practical test it either failed through ignorance of human nature, as Plato himself failed at the court of Dionysius in Sicily, or else, when effectively implemented, as by Demetrius of Phaleron, emerged as nothing but (more or less enlightened) authoritarianism.

The urge to reject the polis took other, more striking forms, of which the most significant was the counterculture preached, and practiced, by the Cynics, and by those Socratics, like Antisthenes, who influenced them (see pp. 612 ff.). Personal asceticism, simplicity of life, the rejection of material possessions and the pleasures of luxury, as well as of all accepted social conventions: these were the characteristics of the Cynic. He was called a “follower of the Dog” from the group’s founder, Diogenes of Sinope (400–325?), known as “the Dog” because he believed that all natural functions were proper, and therefore could and should be performed in public, as a dog performs them, all physis and no nomos. Plato is said to have described him as “Socrates gone mad.” What most people know, or think they know, about Diogenes testifies to the kind of character that breeds legends: that he lived in a tub, that he went through Athens carrying a lamp in broad daylight, in search of a “real man,” and that he told Alexander to stand out of the way because he was keeping the sun off him.21

There was a mythic quality to Diogenes: his personality bred anecdotes, and he collected more of them than almost anyone else in antiquity. The legend, it has been well said, “is a vector of reality.”22 His contempt for the civic side of Athenian life was total. He called “the Dionysiac competitions great spectacles for fools, and the demagogues the mob’s menials,” and thought most men were only a finger’s breadth short of madness. He refused all local allegiances, calling himself a “citizen of the world” (kosmopolitēs).23 When asked what the finest thing in the world was, he replied, promptly, “Freedom of speech.”

With their profession of poverty, not to mention their more exhibitionistic habits, the Cynics were liable to attract some rich dilettanti, but they had comparatively little effect on the fabric of Hellenistic life. Their chief importance is as a psychological symptom, an index of social malaise; and as we have seen, that malaise—the trend toward commercialism, the reaction against the affluence that came with it— had begun long before Alexander’s day. The opening-up of the Persian empire, the subjection of the Greek city-states to external control, simply accelerated and intensified an already existing process. Even Hellenistic ruler cults had their roots in the secular humanism of the Periclean polis. If, as Protagoras claimed, man was the measure of all things, why not of divinity? Lysander, Alexander, Demetrius the Besieger: their achievements and glory were palpable, visible, of this world. Small wonder that, as the years went by, the traditional civic gods were not so much rejected—public ritual has always been the most stubbornly conservative of phenomena—as shunted off into a vague, blissful, remote Elysian heaven, and left with no direct impact on, or interest in, human existence (see pp. 622 ff.). Real men had, in the end, outperformed their own anthropomorphic deities. Menander was well aware of this attitude:24

Onesimos: Smikrines, do you think the gods have so much leisure

That they dish out each individual’s daily ration

Of good and bad?Smikrines: What d’you mean?Onesimos: I’ll tell you.

Say there are—what?—a thousand cities, more or less,

With thirty thousand inhabitants in each. Do the gods

Worry their heads over each single soul’s salvation?Smikrines: What?!

That sounds like a headache of a life to me.

Thus we find the Hellenistic thinker inheriting and developing these various anti-civic, self-regarding modes of thought: the Socratic cultivation of the soul; the Cynic contempt for material wealth, and rejection of social norms; the cultivation of a personal rather than a collective autarkeia, self-sufficiency in the face of political powerlessness and social unrest. To avoid suffering, pain, disturbance (alypia, apathia, ataraxia, and the rest of the negative objectives), to attain and preserve inner calm: these were the chief aims of Hellenistic philosophy. To its ultimate loss, it concentrated on ethics and metaphysics, leaving more practical scientific work to be done by others (see p. 453); thus there is always a certain faint aura of unreality clinging about it. The two systems that came to dominate the Hellenistic world (and indeed the Graeco-Roman culture that succeeded it) were neither Platonism nor the post-Aristotelian thinking of the Peripatetics, but those of the Stoics and Epicureans, the Garden and the Porch. We shall look more closely at their tenets later (see Chaps. 35 and 36); for now, it may help to examine, briefly, the lives and personalities of the two sects’ founders, who both took up residence in Athens toward the close of the fourth century.

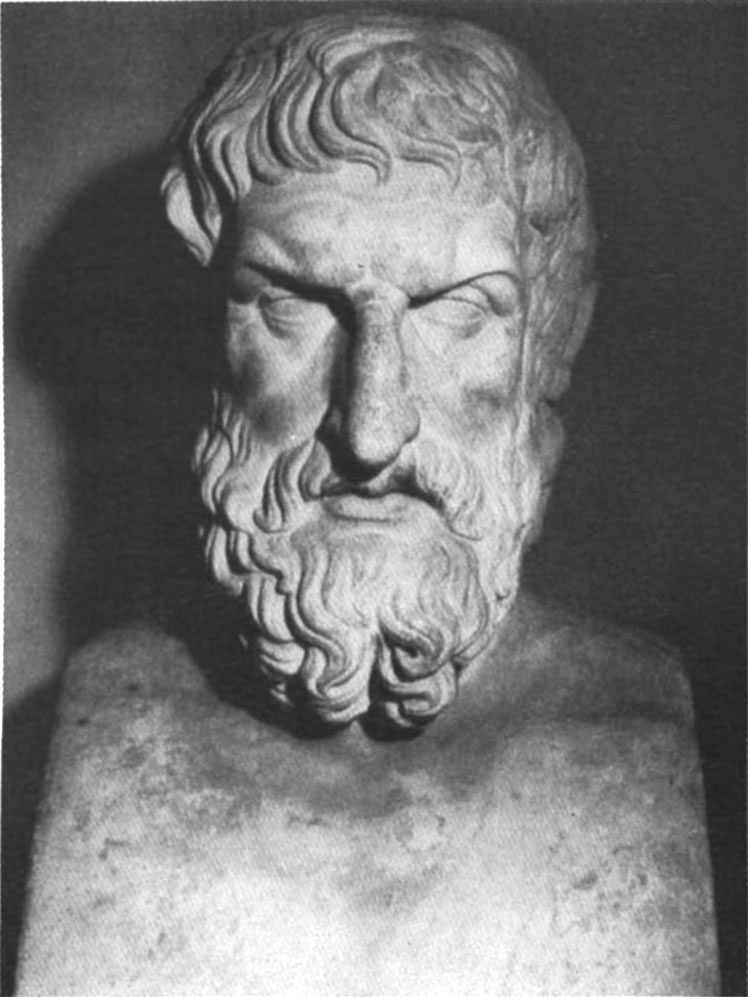

Epicurus, son of Neocles, a Philaid aristocrat (and hence a remote descendant of Miltiades), was born in 341, on the island of Samos,25 where his father had been an Athenian cleruch. The Athenians were expelled from the island by Perdiccas shortly after Alexander’s death (323).26 With his expropriation Neocles seems to have lost all his capital, and to have eked out a living thereafter as a village schoolmaster. Stories of his mother being a spell-chanting herbalist, and his brother a pimp, though possibly slanderous inventions, similarly suggest sudden impoverishment in Epicurus’s family. Prior to this disaster Epicurus had, as an adolescent, already shown a strong interest in philosophy, spurred on by irritation at his teacher’s inability to answer the question “If, as Hesiod says, Chaos was created first, what was Chaos created from?”27 He studied Plato with a master named Pamphilus, and may (whether now or later is unclear) have been introduced by Nausiphanes to the Democritean atomic theory that we find outlined in Lucretius’s great Roman poem De Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things). Pleasure, said Democritus, was the ultimate goal, absence of dread the state of mind to achieve. Epicurus was later to modify this to absence of care: it is possible that his views were to some extent shaped by his family misfortunes.

In 323/2, shortly before the outbreak of the Lamian War, and prior to his family’s expulsion from Samos, Epicurus, now eighteen, went to Athens to do his compulsory two years’ military service as an ephēbos: one of his fellow ephebes, in the next year’s intake, was the future poet Menander. How much time Epicurus had for philosophy during this period of conscription is doubtful. In any case Aristotle had by now—since anti-Macedonian feeling was running high—withdrawn from Athens to retirement in Chalcis.28 If the young conscript attended the immensely popular lectures of Aristotle’s successor Theophrastus now rather than later, he clearly did not find them congenial.29 He is said to have heard Xenocrates lecture in the Academy.30 It is also possible that more practical matters left their mark on him. When Leosthenes died on the battlefield, when Hypereides was executed with ignominy and Demosthenes was driven to suicide (see pp. 10, 11, 36), an intelligent thinker could not but reflect on the advantages of withdrawal, of the nonpolitical life. One of Epicurus’s more famous aphorisms—the subject of a peculiarly silly essay by Plutarch31—was lathe biōsas, which means, in effect, “Get through your life without attracting attention.” During the wars of the Successors this was a piece of advice with practical as well as ethical implications.

The lesson, in the event, came even nearer home. From garrison duty in the forts of Attica Epicurus would, in the normal course, have rejoined his family on Samos in 321. But by now history had overtaken them. The war against Antipater had been fought and lost. Alexander’s decree recalling all exiles had been implemented, and Neocles had lost his Samian estate: Athens (as we know from epigraphical evidence) did not treat the island gently.32 A new, bleak world was dawning for him and those like him. There now began for Epicurus the years of exile and poverty. Philosophy in Greece was a wealthy rentier’s pursuit until the Cynics staked a claim in it, but Epicurus proved himself (as in so many other things) an exception to the rule. He was, in essence, self-made. From 321 until 306 he lived first with his family in Colophon, then alone in Mytilene on Lesbos (311/10), and finally at Lampsacus by the Hellespont (310–306). During this last period he made the permanent friendships of his life—with Metrodorus, who became his deputy, with Hermarchus, who succeeded him, and with the wealthy Idomeneus, who gave him financial backing—and worked out his philosophical system (which might perhaps be more accurately described as a way of life). But all the while politics pursued him: to live without attracting attention, not least for so outspoken a man as Epicurus, proved difficult. His teaching spell in Mytilene (which was under Antigonus One-Eye’s control) coincided with Antigonus’s brief truce with his rivals (see p. 27); the truce once over, Epicurus’s position became difficult. He had antagonized many of the local intellectuals, and seems to have been expelled from the city. He later wrote a pamphlet Against the Philosophers of Mytilene: he had a sharp polemical manner,33 and sometimes it got him into trouble. From Mytilene he moved on to Lampsacus, now held by Antigonus’s adversaries.

Doubtless he could have survived in this peripheral wandering scholar’s existence indefinitely; but by now he had worked out his creed, and if he meant to disseminate it beyond a merely local audience, he had to go to Athens. However much a backwater now in other respects, Athens still remained the unchallenged philosophical center of the Greek world. Moreover, by establishing a cooperative commune of contributing friends, Epicurus had to a great extent remedied his financial problems. In 306, at the age of thirty-five, he moved to Athens, and bought the house and garden by which he is known, where he and his group took up permanent residence. Apart from occasional visits to Lampsacus, where he had formed many friendships, he stayed there until his death (271/0). Outside events largely dictated the timing of his move. He was, predictably, hostile to Cassander and his supporters. He was also in competition with the established schools of Plato and Aristotle. The Lyceum, of course, enjoyed Macedonian support, and from 317 till 307 Athens had been ruled by a puppet dictator who was not only Macedonian-sponsored but also a Peripatetic.

After the change of regime brought about by Demetrius the Besieger a natural reaction against both the Lyceum and the Academy led, as we have seen (p. 49), to a law forbidding the establishment of philosophical schools without prior permission from the Council and the Assembly. But with the rescinding of this law (spring 306), freedom of association was once more recognized, and this time for good.34 Theophrastus had left Athens in 307, in fear of prosecution; when he returned, Epicurus felt safe to make his own move. Once established in Athens he began a lifelong advocacy of his ideals: freedom from fear, whether of the gods or of death; freedom from vain desires and public ambitions. Amid wars, commercial greed, and an increasingly materialistic culture, he preached peace of mind, the unregarded life, withdrawal, the contemplative existence. His ideal, as we shall see, was the nearest thing to medieval monasticism that the ancient world had to offer; and it was similarly reviled and misrepresented by its enemies.

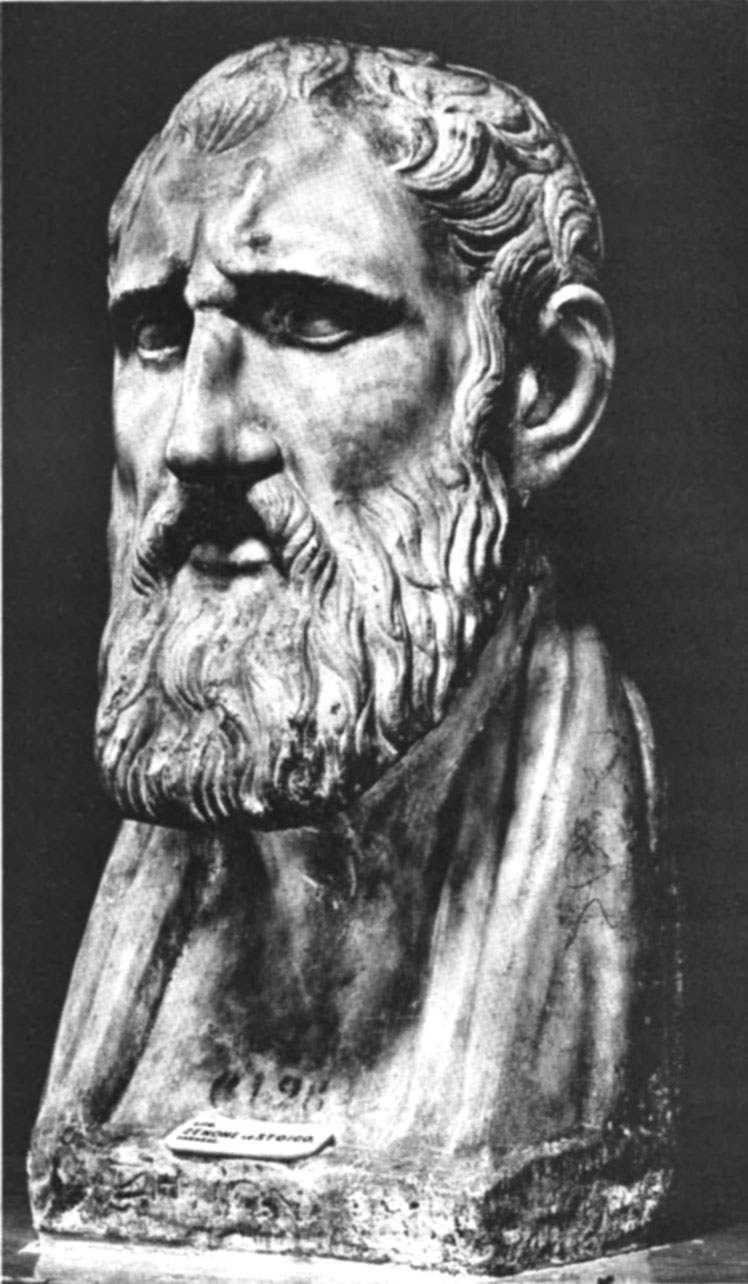

About the same time, a twenty-two-year-old Phoenician named Zeno, from Citium on Cyprus, the son of a merchant, arrived in Athens. Tradition reports that he was shipwrecked near Piraeus. The traditional date of his arrival is 312, during the regime of Demetrius of Phaleron, which may or may not be significant.35 A tall, dark, lean man, it is said: serious of mien, thick-legged, fond of green figs and a place in the sun. Attempts to give an Oriental slant to his thinking have not been successful: Citium, though cosmopolitan, was a Greek city, and there is nothing in the Zenonian corpus that could not be derived from Greek tradition. Indeed, we hear that as a precocious adolescent he had had his father bring back the latest philosophical treatises from Athens along with his more commercial freight. Now he shopped around the lecture halls, tried the Academy, was converted for a while to Cynicism, came to Socrates by way of Antisthenes’ writings, and finally worked out his own system. He is said to have been in a bookseller’s shop one day, soon after his arrival, reading Xenophon’s Memorabilia, and to have asked the bookseller where he could find men like Socrates. Crates the Cynic (see p. 616) was walking past outside, and the bookseller simply said, “Follow that man.”36

Though he always lived frugally,37 Zeno seems to have been solidly well off. The tradition that he arrived with a thousand talents as capital, which he thereafter lent out on bottomry, may be exaggerated, but there is nothing about him that suggests Cynic poverty, and much to support the contention that he was a prudent rentier: he never lacked money for gifts or purchases.38 He began to teach in the Stoa Poikile, or Painted Colonnade (so called because it was used as an art gallery), where he soon became a familiar part of the Athenian scene. Because of this his followers were known as Stoics, or “Colonnaders,” like the poets who had formerly met there. He was much cultivated by King Antigonus Gonatas, whose attentions he seems to have found intermittently tiresome, not having a taste for royal reveling.39 Antigonus invited him to his court (see p. 141), as Archelaus had invited Euripides over a century earlier: Euripides went to Pella and wrote The Bacchae, but Zeno, like Socrates, made polite excuses.

He acquired remarkable respect and admiration in Athens during his lifetime— no easy thing for a philosopher to do, but Zeno was a byword for consistently practicing what he preached. He was honored with a bronze statue and a gold crown; there is even a tradition that the keys of the city were at some time left in his possession for safekeeping.40 When he died, in 262/1, Athens gave him a public tomb, complete with commemorative inscriptions, though he had never become an Athenian citizen, and indeed prided himself on his Cypriot birthright.41 As Kurt von Fritz wrote, “his ethical doctrine gave great comfort to many during the troubled times of the successors of Alexander. According to this doctrine the only real good is virtue, the only real evil moral weakness. Everything else, including poverty, death, pain, is indifferent. Since nobody can deprive the wise man of his virtue he is already in possession of the only real good and therefore happy.”42

Yet in many ways Zeno was an extremely odd cultural hero for the respectable citizens of early third-century Athens. During his Cynic period he advocated unisex dress, upheld sexual freedom between men and women—more specifically, the right of men to joint ownership of women (koinōnia gynaikōn) for purposes of intercourse—was against monogamy, and firmly tolerant of homosexual relations.43 This we learn from surviving references to his early treatise The Republic (Politeia),44 which was well in line with countercultural tendencies, and influenced so powerfully by Cynic ideas that it was said in jest to have been written on Cynosura—Cynosura being not only the name of a well-known local headland, but also, literally interpreted, “the Dog’s tail.”45 Zeno wanted everything that characterized the organized polis—temples, law courts, gymnasia, money, local allegiances—swept away. This constituted a frontal assault on Plato and Aristotle, who both, in their different ways, sought the ideal ruler in the context of the polis, whereas the Cynics held the polis in contempt, not least now that its real power was broken, and saw the wise man as the outsider, the world citizen (kosmopolitēs) standing apart from all regional ties.46 We should, Zeno said, “think all men our fellow demesmen and fellow citizens”—a hint, here, of the later Stoic notion of living in harmony with the cosmic world order (see p. 634). Like Epicurus, like Diogenes, what he offered in those troubled times was not so much a fully reasoned philosophical system as a way of life. It is a nice paradox that this Phoenician iconoclast should have been accepted as a resident guru by the Athenians, as a master who taught their young men “self-fulfillment and self-restraint”;47 an even nicer one that his system should, in the fullness of time, have become an instrument for the instruction of rulers and men of action, from Cato to Marcus Aurelius. Few can have foreseen, as they heard Zeno discourse, striding up and down in the Stoa Poikile, that here was the nucleus of the Greek system of ethics that would take Rome captive—that Stoics, men of the Stoa, would eventually come to include generals, provincial governors, even emperors among their number.