The literature that has survived from the late fourth century and subsequent Hellenistic period shows some striking contrasts with that of the classical era.a In ways these can be misleading. It might appear, for instance, at first sight, as though there had been a total collapse of tragedy, but of course this is not true. Just as many hopeful tragedians, in Athens and elsewhere, were as busy as ever, but for whatever reason—ranging from the vicissitudes of Byzantine taste to plain lack of talent—their work has, except for snippets and fragments, failed to survive. Lycurgus, as we have seen (p. 52), enshrined the triad of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides with bronze statues in the Theater of Dionysus (itself now enlarged and frozen in stone, as though by Medusa), as well as the establishment of a canonical text for their plays. Retrospective hagiolatry does not argue for a strong original movement in any art, and it does look very much as though the aim of tragedy from the fourth century onward was imitative, an attempt to emulate the old masters through skilled mimēsis.

The stress laid on mimēsis by Aristotle in the Poetics, as indeed by Plato in his Republic, is significant.1 The borderline between portraying life and imitating art was, and is, far less clear than is often supposed: from the fourth century onwards successful techniques in realistic depiction at once attracted what is rightly known as the sincerest form of flattery. Just as the stimulus for new architecture now came from external sources (see p. 52), so the social and religious tension between tribe and polis that had fueled Attic tragedy was largely dissipated. Tragedies were produced, but failed to catch fire. They bear about the same relation to a Sophoclean or Euripidean play as do those relentlessly second-rate survivals from the Epic Cycle to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, or the forgotten Victorian three-deckers moldering in major libraries to the work of Trollope, Dickens, and George Eliot.

There was a group of much-touted tragedians, the so-called Pleiad, in Ptolemy Philadelphos’s Alexandria (see p. 177), but their fame seems to have been largely due to royal propaganda and sedulous self-promotion: only one, Lycophron (see pp. 177–79), has any real claim to fame, or notoriety, and that not as a dramatist.2 We know the names of over a hundred fourth-century and Hellenistic tragedians, and possess fragments, substantial in some cases, of their work.3 There were occasional oddities, or historical dramas (e.g., Moschion’s Themistocles), but for the most part these forgotten playwrights went on working the same old mythic plots, perhaps with a certain preference for the exotic. Among the titles credited to Lycophron, for instance, we find an Andromeda, a Heracles, a Suppliants, and a Hippolytus. Literature was now too often feeding exclusively on literature. Many of these plays, significantly, were written to be read rather than acted.4 The general mood is caught to perfection by an anecdote about the fourth-century actor Parmenon, famous for his imitation of a squealing pig: when a real pig was brought on stage, the audience found its squealing sadly inferior, and yelled for Parmenon.5 Those high-voltage civic and tribal conflicts that had sustained fifth-century tragedy’s dialectic were gone for ever, and Attic tragedy became, from the mid-fourth century if not earlier, little more than a fashionable literary exercise. It is a nice paradox that the tradition of Athenian high drama best survived in later comic playwrights’ numerous parodies of famous scenes from tragedy.6

The drama most characteristic of the Hellenistic period—and the sort that most profoundly influenced not only Rome but the whole subsequent course of European theater—was neither tragedy nor comedy in the fifth-century sense of those terms, though it derived elements from both, late Euripides and late Aristophanes in particular, and bore a closer generic relationship to comedy than to anything else. The metamorphosis of Attic Old Comedy, as we can see it in Aristophanes’ Plutus, points the way directly toward Menander; so do the florid excesses and melodramatic romanticism of a tragedy such as Euripides’ Orestes. The transformation is organic and progressive, involving no conscious break.7 Plots become more domestic; increased prominence is given to slave characters (e.g., Cario in the Plutus); there is an incipient tendency to stylize and typologize. What emerges—something wholly predictable in the light of political and social developments—is new to Greek literature: the private comedy of manners. Citizen status in Menander is important only in terms of social prestige (compare all those municipal honorific decrees): there is no real sense of civic involvement.8 Whether comedy by ceasing to be topical became ipso facto universal is quite another matter.9

The plots of this New Comedy are complicated and improbable, littered with long-lost foundlings, twists of mistaken identity, and supposed courtesans who turn out to be virtuous middle-class virgins, more often than not heiresses into the bargain. In sexual matters Aristophanic outspokenness (aischrologia, “dirty talk,” as the fourth century labeled it) has been replaced by coy insinuation (hyponoia), the sure mark of an emergent bourgeois-genteel culture.10 There is always a happy ending. The characters are stereotypes—the crusty old father, the vacuous juvenile lead (head buzzing with romantic yearnings), the cunning slave, the aphoristic cook, the braggart soldier. They are even given stock names.11 Frustrated love is the recurrent theme. The moralizing asides thrown in to give these puffball plays extra weight should not blind us to the fact that they were the precise ancient equivalents of modern situation comedies or soap operas.12 A contemporary reader may find some difficulty in appreciating the reasons for the high status Menander, for instance, enjoyed throughout antiquity (though not, interestingly, during his lifetime). Quintilian praised his rhetorical expertise; Plutarch, who detested Aristophanes, could not think of any better reason for going to the theater than to watch Menander, adding: “When else do intellectuals pack the house for a comedy?” The Alexandrian scholar Aristophanes of Byzantium exclaimed: “Menander, Life—which of you imitated the other?”13 He was the “star” of New Comedy, the “siren of the theaters”; his work was replete with “wit’s holy salt.”14 The only objections raised were to his vocabulary, regarded by some purists as overly colloquial—the cost, one assumes, of imitating life.

Obviously even Hellenistic Greek society was not chiefly remarkable for kidnappings, coincidental rape, and contrived happy resolutions. What, then, did Aristophanes of Byzantium mean when he praised Menander for so skillfully imitating life? The compliment cannot but strike us as paradoxical, since to our way of thinking Menander’s plays are remarkably formulaic and artificial. The truth, I suspect, is that we badly underestimate the staying power of those iron social-cum-literary conventions governing fifth-century Attic drama—conventions that laid down, inter alia, what social class of person could be presented in what type of play, as well as what range of actions, reactions, opinions, language, and vocabulary were appropriate or acceptable for them. Euripides must have raised a few shocked eyebrows by making the husband in his Electra a peasant farmer.15 What stirred admiration for Menander was the (to us, gingerly) way in which he set about broaching these conventions, to put on stage something at least approaching life as it was actually lived, some features of everyday Athenian existence. To borrow a phrase from Dr. Johnson, it was not so much that he did it well as that he did it at all.

As the Hellenistic period proceeds we shall find other characteristic experiments in verse, in particular those of urban pastoral (Theocritus), literary epic (Apollonius Rhodius), or epigram and aetiology (Callimachus). But for the earlier years, the late fourth and early third centuries, poetry is almost exclusively associated with drama. Most serious writing was now in prose, and here we find an enormous amount of ephemeral trash being churned out. Historians, philosophers, epistolographers, rhetoricians, biographers, political pamphleteers, gossipmongers—all were busy. Much of what they wrote was either of little importance per se or else superseded by later work, which cannibalized it ruthlessly. (One critic, perhaps with an axe to grind, wrote no less than six books on the alleged plagiarisms of Menander.)16 Scientists and medical historians developed their own tradition (see pp. 480 ff.), largely independent of the philosophers: physics took one road, metaphysics another, to their mutual loss. In oratory, manner increasingly outstripped matter. Epideictic displays, the logos for its own sake, became all too prevalent. A society that saw an increasing alienation between rural or urban rentiers and actual producers (the so-called banausic element, despised by all those of gentlemanly education) was bound to witness a growth of unreality in its literature: the Golden Fleece pursued in the library, sheep and goats observed at more than arm’s length from behind a thicket of bucolic conventions, literary battles, mock blood. A direct concern with politics was largely restricted to the pamphleteer or the historian, and even then seldom took the form of personal involvement—though Polybius was a striking exception to the rule (see pp. 269 ff.).

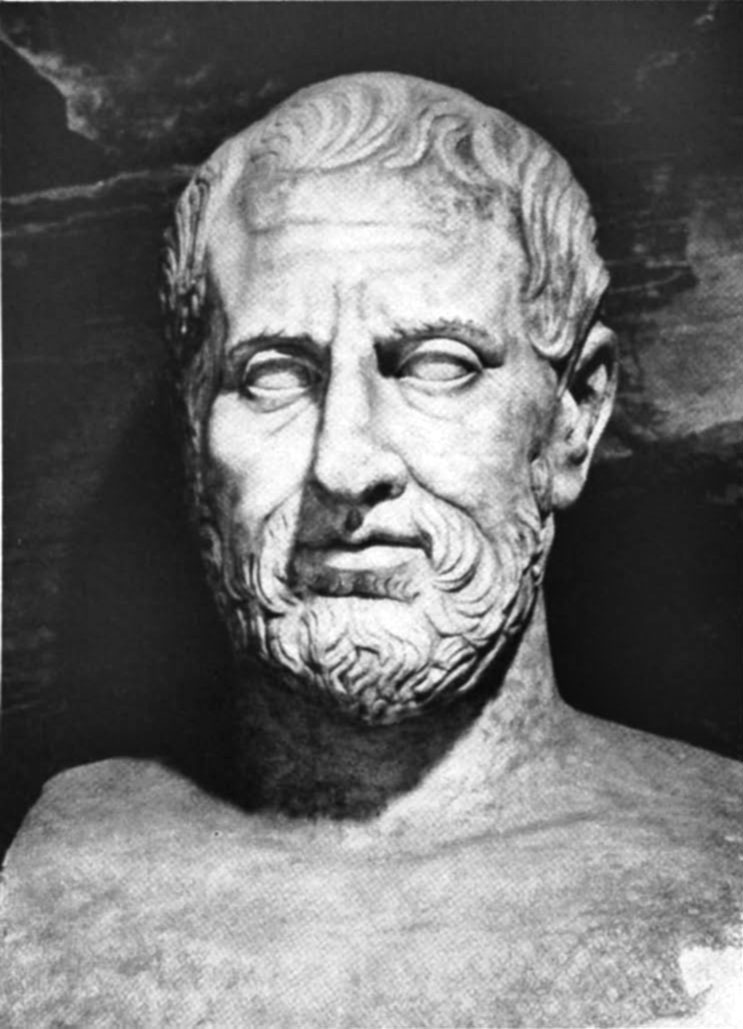

Theophrastus (371/0?-288/5), Aristotle’s successor as head of the Peripatetic school based on the Lyceum, forms an interesting transitional figure between the old and the new styles in literature. Old enough to have known Plato, he was also a typical epigonos of the great thinkers in that, like so many Hellenistic intellectuals, he was more a synthesist, continuator, and teacher than an original pioneer, largely carrying on and developing work begun by Aristotle (though his thought was independent in some areas, e.g. the concept of the soul). He was a popular lecturer, attracting, it is said, crowds of up to two thousand; and Aristotle, deciding that his given name, Tyrtamos, was ugly, renamed him Theophrastus, “Divine Speaker.”17 We have a description of him on the podium, pomaded, dressed in the height of fashion, extravagant and dramatic in his illustrative gestures (“once, mimicking an epicure, he stuck out his tongue and licked his lips”).18 He never married, indeed spoke slightingly of all human passion, and seems to have poured all his energy into his work; we know of well over two hundred books attributed to him, though few have survived.19 We also possess his will, a remarkable social document, dealing with everything from the manumission of favorite slaves to the replacement of explorers’ maps in the Lyceum cloister. Bury me, he said, anywhere convenient in the garden: an interesting sidelight on his personality. A conservative and a man of means, he cultivated Cassander and (perhaps in consequence) enjoyed the friendship and support of Demetrius of Phaleron. This enabled him, though a noncitizen, to own property in Athens, but also got him prosecuted for impiety (without success) by his political enemies. The charge was that he had declared the sovereignty of Tyche in human affairs.20 Like the rest of the philosophers at Athens, he left the country while Sophocles’ restrictive legislation remained in force (above, p. 49).21

Theophrastus’s most solid work was done on botany: we still possess his treatises on the classification and aetiology of plants. It is very tempting to regard his more famous Characters as an essay in the same genre, an attempt to apply the principles of botanical classification to human beings, to typologize men as one would flowers. This reveals an interesting tension between two equally well-marked characteristics of the period. On the one hand we find an increasing tendency toward mimetic realism, which emerges with greatest clarity in the visual arts (see pp. 92 ff.); on the other, there is a drive to abstract and generalize, leading directly to the stock characters of New Comedy. The lively sketches that Theophrastus produced— hardly later than 319, to judge from their topical allusions, the year of Antipater’s death22—contain elements of both, plus strong echoes, both in characterization and in colloquial language, of early Aristophanic characters such as Strepsiades in the Clouds or the Sausage Seller in the Knights. Aristotelian universals are thus offset with quirky, personal details that bring Theophrastus’s portraits instantly to life. Nothing quite like them seems ever to have been produced before; and though they started a long tradition carried on by such figures as Samuel Butler and La Bruyère, nothing quite like them was ever achieved again.

Their purpose is uncertain. It now seems unlikely that (as was once supposed) they had an ethical object, much less that they were put together to show Theophrastus’s student Menander how to illustrate ēthos in his plays—an engaging instance of economy in utilizing sparse available evidence—but I find the currently more fashionable theory that they formed illustrative matter for Theophrastus’s lost Poetics (or, alternatively, his monograph on comedy, also lost) no more convincing.23 Loose similarities with Aristotle’s ethical exempla prove nothing, and the Characters hardly read like models for budding rhetoricians. Jebb’s old theory that Theophrastus wrote these sketches for the private amusement of his friends, and that they were only collected and published after his death, seems no longer to be taken seriously by scholars; but it has, I think, a great deal to be said for it.24

Like most work from this period, the Characters shows comparatively little concern with contemporary events.25 Once or twice, though, we catch a glimpse of what it was like to live in Athens after Crannon. The braggart (23) “will tell you he has had three letters in a row from Antipater, inviting him to Macedonia, and that he’s been offered a license for tax-exempt export of timber from Macedonia, but has refused it, not wanting anyone to run him down as pro-Macedonian” (the most probable date, historically, for this fictional scene is 320/19).26 We sense at once the currents of pro- and anticollaborationist feeling that must have torn Athens in those difficult days. The rumormonger (8), purporting to have witnesses straight from the battlefield, tells a circumstantial story, replete with wishful thinking (cf. p. 19), of how “Polyperchon and the king [i.e., Philip Arrhidaios] have won a battle, and Cassander is a prisoner” (again, the likeliest date for such a rumor is 319, soon after Antipater’s death and Cassander’s revolt). Finally, Theophrastus’s portrait of the oligarch, or authoritarian (26), with his “arrogant taste for power and gain,” his scorn for “the rabble” and “democratic agitators,” his complaints that the rich are being bled to death by obligatory state services (he would clearly have supported Demetrius of Phaleron, who abolished them),27 that the working classes are irresponsible and ungrateful, must have borne a recognizable resemblance to many who supported the oligarchic regime installed by Antipater. As Ussher says, “one feels often that Theophrastus is dealing with flesh-and-blood Athenians, eccentric, puffed-up, or merely nasty—contemporaries well known in the city and recognizable by any reader.”28

What we get from the Characters, on the other hand, is a vivid mosaic of Athenian social life. Athens under Macedonian control, with Phocion and the oligarchs still in power, springs to life here as nowhere else.29 We are given glimpses, as rare as they are valuable, into private homes, the market, the baths, the theater, the gymnasia, temples, and law courts. We meet barbers, bankers, nursemaids, musicians, flute girls and wine merchants, parasites and informers. Pets (as we might guess from the Greek Anthology) are in great demand. Social life, with its dinner parties and public festivals, pays very little attention to the political uncertainties of the day. It is hard to remember, reading Theophrastus’s sketches, that he is portraying the life of a recently defeated, junta-ruled city, with a Macedonian garrison quartered in Piraeus. That provides the historian with a salutary corrective. But above all there is his marvelous, and unending, procession of offbeat, eccentric, nonconformist personalities: the flattering toady patting his patron’s cushions in the theater; the rattle-pate running on by free association; the bore whose own children ask him for a story to put them to sleep; the oaf who sings heartily in the public baths, hammers hobnails into his shoes, and forks hay to the cattle while gulping his own breakfast; the low fellow who shrinks from “no disreputable trade, town crier or hired cook”; the flasher who exposes himself to respectable women (presumably the other sort are regarded as fair game); the absent-minded stumblebum who contrives, after a midnight visit to the outhouse, to lurch down the wrong path and get bitten by his neighbor’s dog; the superstitious man walking around all day with a mouthful of bay leaves; the boil-ridden hairy oaf with black decaying teeth, who not only fails to wash before going to bed with his wife, but even “burps at you in the middle of a drink”; the grossly jovial dinner companion who assures you that his diarrhea was “blacker than this soup”; the military coward who pretends he has to go back for the sword he’s forgotten, and spends his time playing nurse to the wounded; the foot-in-mouth master of tactlessness who watches your servant being flogged and tells you about a slave he had, who—after just such a whipping—went and hanged himself; the slanderers, the ambitious, the misers, the cheeseparing freeloaders.

This fascinating gallery, quite apart from illuminating the whole complex structure of Athenian society in the late fourth century—its idiosyncratic no less than its perennial elements—also forms a significant literary analogue to the new realism in portraiture so characteristic of the whole Hellenistic age (see pp. 107 ff.). Aristotelian mimēsis applied to all forms of artistic expression. When Sophocles claimed that Euripides drew men as they were, whereas he himself portrayed them as they ought to be,30 he was foreshadowing an era when the Euripidean thesis would be treated as axiomatic. How far the rejection of idealism in favor of things-as-they-are can be correlated with the loss of true autonomy is a moot point; it could equally be argued that the new trend was, rather, implicit in Promethean (or Protagorean) humanism, the dangers of which had already been foreseen by Sophocles in the closing lines of a famous chorus from the Antigone.31 What remains incontrovertible is that when we come to the work of Menander, who himself studied under Theophrastus, and seems to have shared his teacher’s typologizing preoccupation with the comédie humaine,32 we find ourselves in a bourgeois world of money making and matchmaking, of comfortable cliché and romantic fantasy, where accuracy of type is matched only by implausibility of plot, and we seem light-years (rather than a bare century) distant from the great moral and political issues that preoccupied the tragedians of fifth-century Athens. Universalism now rested on a solid basis of family values and shared commercial interests.33

Menander, son of Diopeithes of Cephisia, was a wealthy and well-connected Athenian.34 Born in 342/1, he was about five when Philip defeated the Greeks at Chaeronea, and twenty at the time of Crannon and Amorgos (322/1). It was now, while still completing his two years’ service as an ephēbos, that Menander put on his first play, the Orgē (Wrath), and won his first victory with it.35 His instructor in playwriting was the prolific and long-lived Alexis (ca. 375-ca. 275), whose working career spanned both Middle and New Comedy, and from whom Menander borrowed a good deal—the concept of the parasitos (originally a blend of dinner companion, private jester, and freeloader: hence our “parasite”),36 the coining of pseudo-profound aphorisms (marriage as slavery, the virtues of moderation, life as a carnival, old age as the evening of life),37 and, possibly, some of his plots (e.g., Into the Well at once brings Menander’s Dyskolos to mind).38 But Menander totally lacks the satirical pungency that makes the loss of Alexis’s work, except for tantalizing fragments, particularly regrettable. “Everyone agrees,” he once wrote, “that all top people are rich: you never see a blue-blooded beggar.”39

Menander wrote over a hundred plays, yet won first prize only eight times.40 He was drowned in his fifties while swimming off Piraeus (292/1): Pausanias locates his tomb beside the Athens—Piraeus highway, near Euripides’ cenotaph.41 He is said to have been a handsome man, and his surviving portraits support this;42 but there is also a tradition that he suffered from a pronounced squint, now strikingly confirmed by the famous mosaic found in Mytilene.43 It was probably through his connection with Theophrastus that he came to be an intimate friend of Demetrius of Phaleron. Phaedrus, in one of his fables, draws an unpleasantly plausible picture of the Athenian elite hastening to pay court to Demetrius, to “kiss the oppressor’s hand” while privately grumbling about their loss of freedom. Among the last in line, Phaedrus says, who came sneaking in only because “absence might be a mark against them,” was Menander: elegant, languid, pomaded, mincing along in a loose flowing robe. “And who,” Phaedrus makes Demetrius exclaim, “is that screaming queen who has the nerve to approach me in such a getup?” “That,” his attendants told him, “is Menander, the playwright.” At which Demetrius, instantly changing tack, exclaimed: “The most handsome man I ever saw!”44 If we relate this fable to what we know of Demetrius’s own dandified, not to say epicene, habits (above, pp. 46–47), it is hard to resist the conclusion that Menander, like many an artist since, was out to win influence in high places, and knew, in this case, just how to do it. Far from being homosexual, he was “absolutely crazy about women”; but the same source to which we owe that description reminds us that he had “sharp wits.”45 In any case, his intimacy with Demetrius was such that after the dictator’s fall he only just avoided prosecution simply (so far as we can tell) on the basis of guilt through association.46

How far he should be assumed, because of these associations, to have been himself an advocate of authoritarian or plutocratic rule is an open question. As one scholar put it, “pupils may be transitory or inattentive, and friends do not necessarily think alike.”47 Yet it is hard to visualize this crowd-pleasing middle-of-the-roader, platitudinous if ironic,48 as a liberal crusader. He would seem rather, on what little evidence we have, to have shared the chameleon qualities attributed to Alcibiades,49 and to have worked hard to ingratiate himself with whatever regime might be in power. It has even been suggested that his sympathy with pro-Macedonian government was one reason why his plays, at least during his lifetime, lacked more popular success. This I doubt: while the fuss about P. G. Wodehouse’s German broadcasts was at its height, his books continued to sell in undiminished quantities. The parallel is interesting in other ways, too, since the world Menander portrays is almost as stylized as that of Blandings Castle or the Drones Club, and indeed contains many very similar characters: Bertie Wooster is not at all unlike one of Menander’s well-heeled young suitors, potty with innocent passion and misunderstood good intentions, while his clever, manipulative slaves have many characteristics in common with Jeeves.50 Both writers, moreover, lived in highly disturbed times; both, except in the most oblique ways, ignored these disturbances in their work. One scholar wonders whether the Dyskolos (see below) may not carry political overtones, with the old curmudgeon of the title symbolizing the Athenian dēmos forced to accept the unwelcome regime of Demetrius of Phaleron:51 I find this a grotesquely improbable notion.

The keynote, rather, is (as in those late Euripidean choruses) escapism. What the members of an Athenian audience wanted, in 316,52 was to get away from their own grim condition, a not-unfamiliar phenomenon today. It had not been all that long since the defeat at Crannon, Phocion’s hysterically orchestrated execution, the brief but violent restoration of democracy. To that extent these Athenian spectators are much more like a modern soap-opera audience than the constantly involved, and politicized, dēmos of the fifth century, on whose vote the fate of Athens hung daily. Also, the abolition of the state subsidy (theōrikon) for theatergoing must have substantially modified the composition of the audience as such, restricting it for the most part to prosperous bourgeois citizens and their would-be emulators, all only too eager to forget, for a while, the harsh realities of public life, and53

to be entertained instead by the consoling and idealised picture of stable, middle-class family life, where the problems of money and sexual desire, of misunderstandings and flawed relationships, were more limited in scale, always fathomable, and always resolved in the inevitable happy ending which celebrated and cemented family unity.

It is quite possible that in those anarchic times, when the reduced fleet of Athens could no longer adequately police the Aegean, and law and order too often went by default, there in fact were kidnappings of heiresses by pirates, especially from the more exposed coastal districts of Attica. It is certain that exposure (in addition to abortion and primitive contraception) was practiced by Greek families, and the rescue of foundlings by rural peasants, childless or not, may have been a more common phenomenon in real life than we suppose. Yet when all allowances have been made, the world we enter here is immeasurably remote from that of Oedipus or Antigone. Technically, too, we have come a long way from the obscenity, political involvement, and episodic vaudeville structure of an Aristophanic comedy. Agōn and parabasis, choral lyrics integrated with the action—all are gone. Instead we have the sequence of five acts familiar from later European drama, divided by choral interludes that have little if anything to do with the action, and do not survive in our manuscripts, which merely mark the points where they occur.54

The escapist motif is unmistakable. For most Athenians of the classical era the Agora, the hub of the polis, formed the center of the world, whereas Menander as often as not sets his scene out in the Attic countryside. His characters, rustic or urban, are concerned with their own rather than the state’s affairs, with money and marriage, not with politics. The nearest we come to civic factionalism is the tired exchange of stereotyped insults (“You drivel-spouting troublemaker”; “You authoritarian bastard”) between two characters in the Sicyonians.55 Menander’s soldiers— Polemon in the Perikeiromenē (Shorn Woman), Thrasonides in the Misoumenos (Unpopular Man)—are figures of fun, their lust well contained by romantic yearnings;56 but the real unemployed mercenaries and soldiers of fortune who roamed the countryside (see p. 313) tended to be unpleasant toughs much given to rape and larceny. Murder and serious illness, similarly, are taboo subjects in the plays.57 Rape is a recurrent motif, but only as a stylized determinant of plot: it normally takes place at a nocturnal festival, and more often than not the rapist later, all-unknowing, marries his victim, who regularly bears a child as the result of his earlier attentions.58

Pimps and parasites, gold-hearted whores, mysterious pregnancies, mistaken identities, complex and ill-motivated social deceptions, family legacies—these are the ingredients that go to form Menander’s stock in trade. There is the same quiet yet stubborn preoccupation with good (i.e., financially profitable and socially improving) matches that we find in, say, Jane Austen, though without her incomparable psychological insight. No one in this world, with very few exceptions, has a job or does any serious work except on his own estate: Menander’s society consists, in essence, of rural landowners, rentiers, and their employees, slaves, or hangers-on (e.g., the recurrent high-class cooks). We meet the occasional merchant, but his line of merchandise, as in Dickens, tends to remain vague. Metics, resident aliens, though an influential group, are conspicuous by their absence.59 The element of Chance or Fortune, Tyche, tends as always to be overworked,60 though this may in some degree be because Menander is dealing with an agricultural society where (political vicissitudes quite apart) luck formed an integral element of the year’s balance sheet, and technological foresight remained minimal (see p. 469).

Till 1907, the date of Lefebvre’s publication of the Cairo codex,61 our verdict on Menander had to rest on brief quotations and the opinions of ancient critics: his works were all lost (except through the indirect medium of Roman adaptations) before the eighth century A.D. Three plays, The Arbitrators (Epitrepontes), The Woman of Samos (Samia), and The Shorn Girl (Perikeiromenē, variously rendered as The Rape of the Locks or The Unkindest Cut), were well enough represented in the codex to give a general idea of their plot, structure, and, above all, their language and style. The overall impression was of relentlessly low-key colloquial dialogue, recreating (with a discreet infusion of popularized ethics) the platitudinous exchanges of day-to-day life, and written in an unpretentious Attic already well on its way to becoming koinē—that bastardized vernacular lingua franca of the Hellenistic world, now enshrined for ever in the New Testament.62

Finally, in 1959, came the most important find: virtually the whole of an early play by Menander, the Dyskolos (variously translated as The Curmudgeon, The Bad-Tempered Man, The Peevish Fellow, The Grouch, or even Grumpy).63 It is now possible to form a fair picture of his work as a whole, since there exist also numerous citations and fragments from other plays: the total body of surviving work—including the bulk of The Woman of Samos and of a further play, The Shield (Aspis), published in 1969 from the same papyrus book as the Dyskolos64—fills a fat volume.65 Yet far from enhancing our opinion of a playwright on whom earlier judgments tended, because of the fragmentary corpus, either to be held in abeyance or else to echo the eulogies of antiquity, the publication of the Dyskolos leaves us all too aware that the standards of the late fourth century B.C. are very different from ours. Produced in January 316, a few months after Demetrius of Phaleron became epimelētēs of Athens, it won the young playwright what was probably his second victory. The play’s situation and characters—not by accident, I would maintain—bear even less direct relation than is usual with Menander to contemporary affairs.66 A fifth-century audience had had no qualms about relegating Sophocles’ Oedipus to second place (it was defeated by a production of Aeschylus’s nephew Philocles);67 this new generation of Athenians was, clearly, easier to please.

Since the Dyskolos is our only complete play by Menander, and since opinions are fairly sharply divided as to its merits, it may be advantageous, at this point, to give a fairly detailed description of its plot. After an introductory prologue by the god Pan, setting the scene and explaining the action (1–49), we are presented with a stock Menandrian situation (50–188): a rich young man, Sostratos, sighing with love for a girl he has encountered, while his companion, Chaireas, works out a plan for her conquest. If she’s a whore, Chaireas says airily, we’ll burn her door down. If, on the other hand, she turns out to be a freeborn girl with marriage in view, then “find out about her family, income, personal habits” (65–66). Sostratos has sent off his huntsman, Pyrrhias, to make just such inquiries. Pyrrhias now enters, very much in disarray, but with the information that the girl is, indeed, freeborn. His disheveled state is due to the fact that he has just been run off her father’s farm by the father himself, Cnemon, the curmudgeon of the title, and the kind of farmer who today would carry a prominently racked rifle or shotgun in his pickup. Hardly has Pyrrhias got this information out before Cnemon storms in, mangling mythology and ranting about trespass. From the opening lines every character seems both undermotivated and, for no good or sufficient reason, in a permanent hysterical frenzy.

At this point it might seem a simple solution to Sostratos’s problem if he were to tell Myrrhine, Cnemon’s daughter, and, if it comes to that, Cnemon himself, just what he has in mind. But instead (since with Menander tortuous gambits must do duty for a plot) he goes off to consult with Geta, a clever slave of his father’s (181 ff.). Enter then Myrrhine, the daughter, complaining that their old servant has dropped a bucket down the well. Sostratos, dizzy with love, gets water for her. The scene between them is observed by Daos, the slave of Cnemon’s stepson, Gorgias, who just happens to own the only other house in the immediate neighborhood, where (to complicate things further) he lives with the curmudgeon’s separated wife. Daos, thinking Sostratos is aiming to seduce Myrrhine rather than marry her, goes and tells his master. Gorgias, an overeducated rhetorician who talks like a book, in elaborate bipartite sentences,68 confronts Sostratos with this suspicion. Sostratos manages to convince Gorgias that his intentions are strictly honorable.

The two young men now concoct an improbable plan for Sostratos to work in the fields alongside Gorgias, the point being that Cnemon cannot stand the sight of gentlemen of leisure. Sostratos agrees, but is soon complaining that the mattock he has been given weighs a ton (390). This scene is followed by the appearance of Geta, together with Sikon, a cook, dragging a sheep: Sostratos’s mother has had a bad dream about her son, and is going to sacrifice to Pan (393 ff.). The dream, of course, is that Sostratos was in farm clothes and working his neighbor’s land with a mattock. Cnemon sees the sacrificial procession arrive, and decides, with no good reason given, that it is unsafe to leave his house unattended (427 ff.). His endemic suspicions and ingrained rural sourness are not provided with any adequate roots in the action; he is simply a walking embodiment of crabbed misanthropy, a Theophrastan humor, the eternal angry farmer swearing at trespassers. (As Pan explains early in the prologue, Cnemon lives in a hill region “where those who can, farm the rocks”: perhaps that should suffice.) Meanwhile Geta and Sikon try to borrow pots and pans from him, with predictable results; Sostratos staggers in half-dead from fieldwork, and not even having had the chance to talk with Cnemon; everyone talks, boringly and irrelevantly, about the sacrifice;69 and Cnemon discovers that his mattock is down the well. This takes us to the end of the third act.

The fourth act at least provides a little fortuitous action (620 ff.). Cnemon falls down the well, where, I cannot help feeling, it would have been more sensible to leave him. Gorgias and Sostratos, however, haul him up offstage, Sostratos in erotic ecstasy because Myrrhine is there beside him, making a loud Greek female fuss about her poor father. The rescue is described by Sostratos in a brisk little parody of a tragic messenger speech (666–90). The rescued Cnemon now delivers a portentous harangue about realizing for the first time that “a man needs someone, someone there and ready to help him out” (708–47).70 He then promises to adopt Gorgias, already his stepson, as his legal son—a move that makes me wonder about the claim that “Gorgias’s motives in saving him from the well are purely disinterested”71—and tells him to find a husband for Myrrhine. “I won’t be able to,” Cnemon admits, a trifle disingenuously; “not a single one will ever please me.” Finally he comes out with one statement, however platitudinous, that has interest, because it suggests Cynic influence: “If everyone was like me, there’d be no courts, men wouldn’t drag each other off to prison, there’d be no war—everyone would be happy with middling possessions” (743–45).

This direct assault, in a prize-winning play, on everything from civic involvement to due process under law—everything, in fact, that characterized the polis in its heyday—is of considerable social significance. The rejection of war, once the favorite inter-polis sport, is particularly interesting. Yet nothing comes of this interpolated sermon in any dramatic sense; it bears no more relation to the substance of the play than does a commercial to the program it interrupts. Instead, the last act is devoted to a perfunctory knotting-up of the various frustrated betrothals. Gorgias talks Cnemon into letting Sostratos marry Myrrhine (Myrrhine herself, characteristically, is not consulted). Sostratos’s father, Callippides, arrives for the sacrifice and balks at the idea of letting his daughter marry Gorgias, saying he does not intend to have two paupers in the family at once (775 ff.). Sostratos, suddenly acquiring Gorgias’s rhetorical prolixity for the occasion, then reads his father a mini-lecture on not being stingy—“Fortune will take everything from you and bestow it on someone else, who may well not deserve it” (797 ff.). Invest in everyone, Sostratos says. Then if you ever come a cropper, you’ll get help in return (809–10). Instead of dressing his son down, not only for gross impertinence but also for the appallingly cliché-ridden form that his impertinence takes, Callipides at once gives in. The double betrothal will take place. The cook Sikon and Geta the slave then have a little rough horseplay with the sleeping Cnemon; after a rude awakening he is finally worn down by their jolly violence and agrees to attend the feast, grumbling as he goes. (And who could blame him?) So the play ends, and we are left with the problem of whether Menander imitated life or vice versa.

Now it is, I would concede, often easy enough to make a serious writer look ridiculous by merely potting his plots: Clifton Fadiman’s demolition of the novels of Faulkner is a classic case in point.72 On the other hand, it is also undeniable that Menander stands as ancestor to the whole European comedy of manners, from Molière and Goldoni by way of Sheridan to Shaw, Wilde, and their modern epigonoi such as Coward, Simon, and Ayckbourn. The near-unanimous verdict of antiquity may be hard to understand, but it is also hard to argue with it, to insist that the emperor may, after all, lack the gorgeous apparel claimed for him. There is, too, something infinitely ironic—Tyche in one of her more malicious aspects—about the mere possibility that now, at last, that the miracle has happened, and a whole Greek prize-winning drama has been resurrected from the sands of Egypt, it could conceivably be regarded as second-rate hackwork. One can hardly blame the papyrologists and textual critics who have labored so long and so minutely on Bodmer Papyrus IV for not being disposed to admit that their collective intellectual endeavors have been expended on such lightweight matter. Yet Sir William Tarn—a formidable Hellenistic scholar, though neither a papyrologist nor a textual critic—dismissed Menander and his imitators as “about the dreariest desert in literature,” and that verdict cannot be lightly set aside.73

Menander’s defenders have naturally done their best to disprove it. Their regular line is to ignore the substance of the attacks, and to stress that Menander should really be admired for something quite different, such as the social and psychological realism of his characterization,74 his Platonic, even Aeschylean, concern with humanity,75 his elegance, emotional subtlety, and complex dramatic skills,76 his energy, power, and sense of purpose,77 or his significant realistic detail, anti-typical characterization, clever word games, and deflating parody (“secularization”).78 The list could be extended: most of the qualities selected for praise, we may note, are hard to prove or disprove. Yet sooner or later even Menander’s most devoted admirers are forced to concede many of those faults we have already noted: the hackneyed recurrent motifs, the artificial coincidences, the repeated use of grotesque devices (e.g., rape at a festival) to precipitate action. These are then excused by a timely reminder that Menander had, after all, a very different audience to deal with from that of his fifth-century predecessors, and needed (despite his large private income!) “to pamper and not antagonise them in his competitive struggle for success,” an argument that Euripides, for one, would have treated with the contempt it deserves.79

In other words, we are being asked to accept as fact that the soap-opera plots, the popular aphorisms, the commonplace moral values, stock characters, stereo-typed opinions, and cliché-ridden dialogue were all concessions made by this intellectual and creative paragon to the Aunt Ednas of the Athenian bourgeoisie, whereas any flashes of brilliance that can be detected in his work are ascribed to the genius he was forced to restrain while pursuing the bitch-goddess success. In that case, quite apart from the innate immorality of such a proceeding (once a whore, always a whore, as Orwell remarked in a very similar modern context), one can only point out that Menander’s essay in self-prostitution did him singularly little good. Eight victories in over a hundred attempts is hardly the record of a clever crowd-pleaser: Hugh Walpole did far better. Alternatively, a diametrically opposite case has been argued (at least one scholar has, on different occasions, tried both approaches), which asserts that Menander’s comedies were caviar to the general, that he did not make enough concessions, and was, indeed, defeated so often because “his audiences did not appreciate the delicate nuances and individualised refinements of his art.”80

Examination of the surviving oeuvre reveals a good deal of special pleading and hyperbole in all these claims. The supposedly subtle characterization is both broad and one-dimensional, based on generalized ethics rather than psychological insight. The wise aphorisms turn out to be crackerbarrel commonplaces. Too much of the dialogue is flaccid and colloquial pseudorealism, little relieved by occasional references to such things as decaying battlefield corpses,81 a phenomenon with far less shock value for that harsh age than for our own, and anyway already familiar in previous literature from Homer and Archilochus onwards. Significant transformations (e.g., Cnemon’s change-of-heart speech in the Dyskolos), are badly undermotivated.

The rest of the corpus similarly abounds in situational idiocies. Take the Arbitrators (Epitrepontes), another much-praised Menandrian torso: a young stud, Charisios (“Charmer”), having raped one Pamphile (“Darling”) during the inevitable night festival, gets married, only to discover, first, that the girl he married has a baby five months later, and then, as a dénouement, that she was also the girl he raped, and that the child is therefore presumptively his. We get the usual array of wisecracking cooks and smart slaves, rings and tokens, implausible coincidences. Disbelief, though suspended, keeps breaking in. Why, we may legitimately ask, did Charisios not have the problem of her five-months’ child out face-to-face with his wife instead of listening to the servants? Why, instead, does he simply walk out on her in a huff and take up with Habrotonon, a guitar-strumming floozy with the usual heart of gold? No play otherwise, the cynic might answer; rational plots are not exactly Menander’s forte.

Perhaps more important than the ongoing debate about Menander’s literary value to us is any attempt we can make to explain his appeal to his contemporaries and, a fortiori, to succeeding generations in the Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman world. We will not attain this end by upgrading his aims, or outlook, to satisfy our own preoccupations. There is, now, more than enough material on which to form a judgment, and it all tells the same story. While his Athenian spectators appreciated mimēsis insofar as this delineated popular character types, from grouchy old farmer to braggart soldier, from conniving slave to lovesick youth, they had no time at all for tragic involvement in the old fifth-century sense, much less for political satire or for broad Aristophanic humor. Realism, mimēsis, became, indeed, a far preferable alternative to what Gregers Werle in The Wild Duck described as “the claims of the ideal.” The passion for achieving a likeness, in literature as in the visual arts,82 repudiated everything that Daedalic sculptors or Platonic thinking had stood for. It is no accident that from Aristophanes’ Plutus onwards the scene of each comedy is normally restricted to that ne plus ultra of mundane realism, a street with housefronts, or that plays are named after professional types (Farmer, Doctor, Parasite), or courtesans.83

The free spirit no longer explored Cloudcuckooland, harrowed Hades, or soared heavenwards on giant dung beetles; it moved, now, at the discretion of Macedonia, and in Pella, notoriously, creative endeavor was an imported commodity. The mood was both genteel and escapist: a middle-class obsession with money, offset by a coy, almost prim, rejection of peasant obscenity; resignation, or indifference, to the loss of political independence; an upgrading of family values; a sanitization of unpleasant realities such as rape or abduction; the deployment of romantic fantasy to camouflage unpalatable social facts. When we read Aristophanes or the fifth-century tragedians, we know, instantly, that we are in the presence of something astonishing and unique, both socially and in literature. Even the fragments of Menander’s teacher, Alexis, crackle with originality and life.84 But what Menander himself mirrors for us, with deadly accuracy, is something at once less uplifting and more familiar: the flawed, self-seeking nature of our own common humanity.

All this perhaps lends a rather unexpected overtone to the famous anecdote in Plutarch about Menander still not having written his play as the festival for which it was meant approached.85 When a friend inquired, in some anxiety, about his progress, Menander replied: “Oh, the comedy’s finished: I’ve got my theme—all I have to do now is write the dialogue.” That, alas—formula dressed out in platitude—is just how his work reads. The notion of all else being secondary to plot is, of course, a staple of Aristotelian criticism;86 but critics who apply it to Menander do so at their peril.87 Daos, the slave in the Aspis, may be as full of sly literary quotations as Aeschylus and Euripides in the Frogs,88 or the characters in the Epitrepontes may cite Euripides himself at one another, and on occasion philosophize in his manner;89 the overall result is still a sad falling-off from Attic Old Comedy, let alone the fifth-century tragedians. But it was (a fact of prime historical importance) what, in his lifetime, the people who mattered, that is, the theatergoing propertied classes, wanted; and it caught the admiration of ancient critics after his death. If we can appreciate why—and part, at least, of the answer should emerge during the course of this book—our understanding of the Hellenistic age will be immeasurably enhanced.

a Apart from the texts that have survived intact, and the fragments of well-known (and much copied) authors such as Callimachus, a whole host of minor elegists, tragedians, epic poets, epigrammatists, and others were busily at work throughout our period. Till recently—the tragedians excepted—Powell’s Collectanea Alexandrina (Oxford, 1925) was the only accessible collection of this material, or what survived of it. Now the field has been extended almost beyond recognition by the publication of Hugh Lloyd-Jones’ and Peter Parsons’ magisterial Supplementum Hellenisticum (Berlin and New York, 1983), containing the remains of about 150 little-known authors (in addition to those assembled by Powell) and numerous unattributed fragments and excerpts. To browse through this collection gives one the median flavor, as it were, of Hellenistic poetry in a way nothing else could do. A translation of even a representative selection from this wide-ranging material would be a real service to literature.