When Alexander the Great was in Ephesus (334), he sat for his portrait, astride his warhorse, Bucephalas, for the famous Greek painter Apelles,1 who had worked for Alexander’s father, Philip, and was later to serve Ptolemy—a tribute, one feels, to his diplomatic no less than his artistic skills. When he painted Antigonus One-Eye, he executed the portrait in three-quarter profile to mask the old general’s empty eye socket;2 perhaps he had done the same for Philip. The finished picture of Alexander, however, did not meet with the king’s approval: Alexander believed, to put it mildly, in self-alignment with the ideal (whether divine or merely Achillean), and expected his portraitists to convey that quality in their work. Apelles, by way of self-justification, had Bucephalas brought into the studio and placed in front of the finished work—probably a panel painting on wood, a more popular medium by that time than the mural. When the live horse neighed at its painted likeness, Apelles said: “You see, O King, the horse is really a far better judge of art than you are.”3

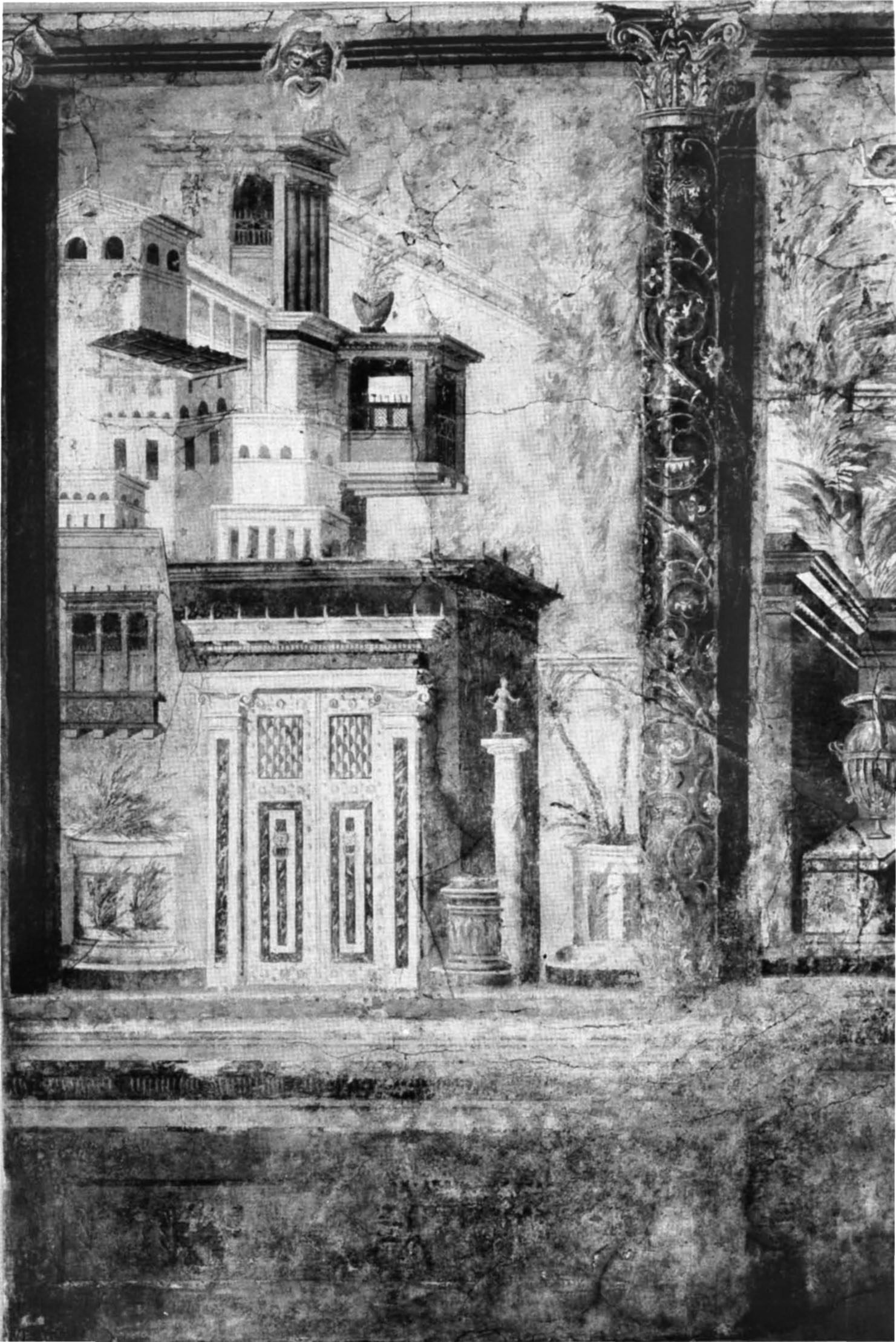

Apelles’ comment enshrines the central criterion of visual art throughout the Hellenistic and Graeco-Roman period: deceptively realistic naturalism (alētheia, veritas).4 Anecdotes of this kind abound. We hear, for instance, of birds pecking at one picture by Zeuxis because they mistook his painted grapes for the real thing.5 (He afterwards painted a “Boy with Grapes,” and the same thing happened: Zeuxis remarked, in irritation, that he must have painted the grapes better than the boy; otherwise, the birds would have been scared off.) Ars est celare artem: those later trompe-l’oeil effects in which, with cunning perspective, doors, windows, whole landscapes were painted on blank inner walls, as though on a stage backdrop, simply took the principle one stage further, emphasizing that obsession with theatrical imagery—masks, actors, scenes from plays in performance—that formed so prominent a feature of the Hellenistic cultural scene.6 Such effects could sometimes be almost too successful. Protogenes is said to have painted a satyr scene with a partridge in it: the bird was so realistically done that no one had eyes for anything else—tame partridges are said to have besieged it with mating calls—and the artist, infuriated, painted it out.7

Perspective provided the link between the real world and artistic illusion,8 a divergence from the “true” mimēsis that Plato, for one, regarded with intense suspicion.9 Realism was thus very literally in the eye of the beholder,10 and could be manufactured by an expert at will: here the visual artist was simply doing, in his own terms, what a rhetorician like Gorgias, equally given to the art of illusion (apatē), had recommended. Lysippus of Sicyon, the late fourth-century sculptor, said that, whereas his predecessors had portrayed men as they were, he made them as they appeared to be,11 a nice variation on Sophocles’ comparison of himself and Euripides (above, p. 71). Since it always hovered on the edge of caricature (see p. 109), trompe-l’oeil realism could without difficulty be reconciled with the era’s countertrend, baroque fantasy, a progressive cultivation of the grotesque, already discernible in Aristophanes’ later comedies, from the Birds (414) onwards.

As in literature and philosophy, so in architecture and the visual arts we find social and political change faithfully reflected by new styles, new themes, new conventions.12 The trend is away from classicism, away from an art that “had taken group experience and a faith in the attainments of an entire culture as its principal theme.”13 These changes are, again, noticeable from an earlier date than is often supposed, and, as in other fields, the crucial period is, roughly, between 380 and 370. In a remarkable survey, Blanche Brown lists many of the factors leading to the erosion of the polis: autocratic takeovers in Sicily, Thessaly, Caria, and elsewhere; the rise of federations; the spread of panhellenism; the emergence of Macedonia as a strong and successful military monarchy; the association of the new rulers’ courts with cultural patronage on a large scale, and (through the same channels) with self-promoting propaganda in the form of grandiose architecture or encomiastic literature.14 Professionalism—military, political, financial, legal, theatrical, athletic—replaced the old civic ideal of amateur all-rounders. The cult of personality, long shunned, and with good reason, in the polis (see p. 108), began to gain ground very soon after the Peloponnesian War. Honorific portraits of the Athenian admiral Conon and his son Timotheus were set up—on the Acropolis, too!—in 393,15 and the Spartan general Lysander had festivals in his honor and was actually worshipped as a god.16 Such a trend not only paved the way for Hellenistic monarchy and ruler cults; it also, inevitably, brought a new realism to representative art.

Some of the most significant, and most easily explained, departures can be found in the new building programs of the late fourth and early third centuries. As we have seen (above, p. 52), the Greek city-states of the mainland, Athens in particular, largely abandoned those major religious-cum-civic constructions that had been the hallmark of the fifth century. One obvious reason for this was financial stringency: as mere satellites of Macedonia, stripped of their old revenues, they could no longer well afford such gestures. Besides, major monuments like the Parthenon had been an expression of civic self-confidence, of pride in supremacy, a tribute to the city’s guardian deities and human resources. After Chaeronea, who could make such a claim in Athens? So when the fourth-century finance minister Lycurgus (390-325/4), in direct emulation of Pericles, launched his building program to offset Philip’s victory, he concentrated on more secular and commercial matters.17 Such a step was, in a sense, the reductio ad absurdum of Protagorean humanism.

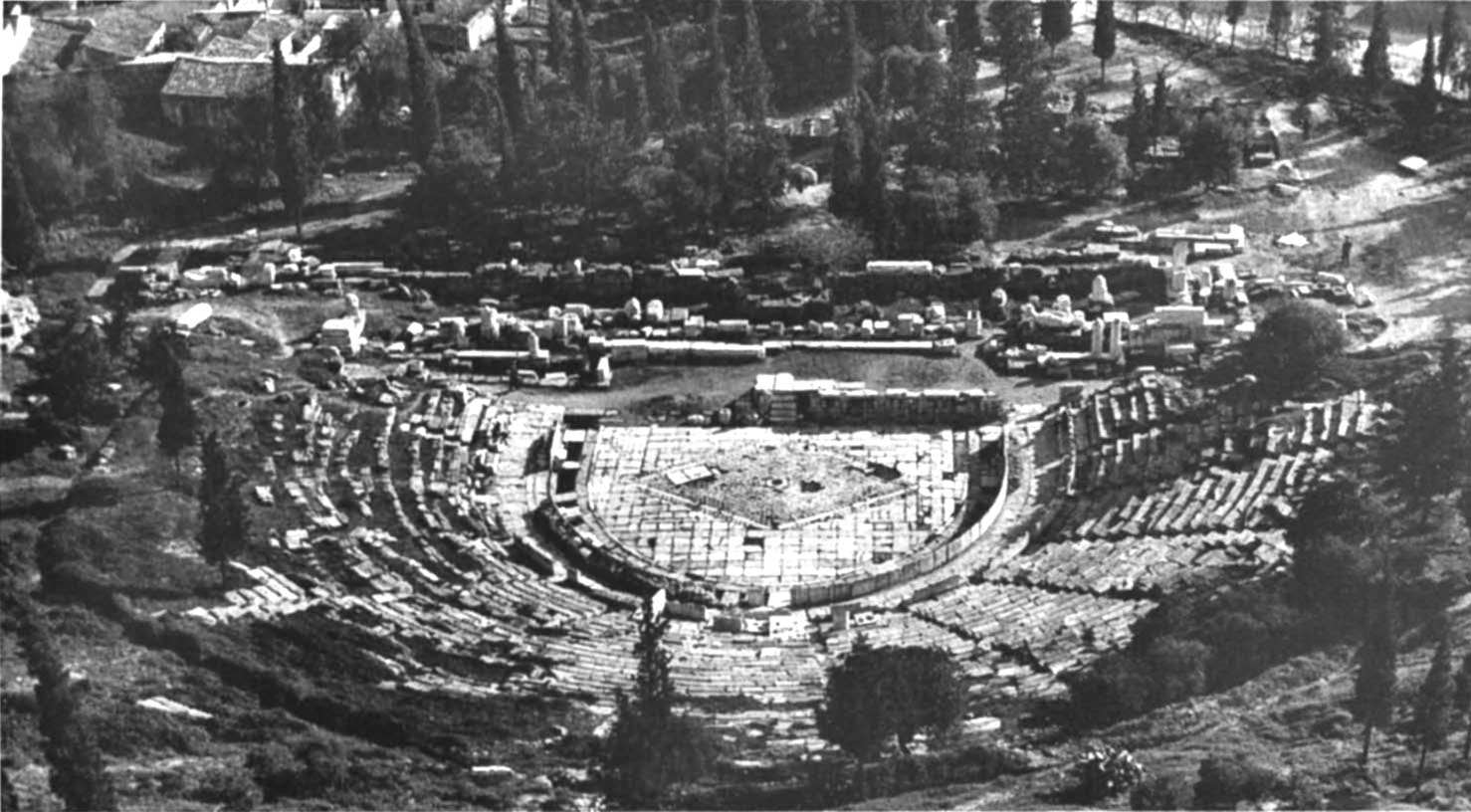

It was in this mood that the Athenians, during Antipater’s regency (above, p. 8), built the Panathenaic stadium and the arsenal, and began an ambitious peristyle on the northeast side of the Agora, to embellish their new law courts. We may note that the peristyle was never finished: indeed, the number of grandiose projects begun in Athens about this time, but never brought to completion, is in itself significant. The restyling of the Pnyx, with stoas to shelter citizens from the rain, was one such aborted project; the portico for the Hall of the Mysteries (telestērion) at Eleusis was another.18 In all cases the drying-up of funds was probably a major factor, though the renovation of the Theater of Dionysus seems to have been due, in part at least, to the belief that it would make a more convenient place of assembly than the Pnyx, and was therefore (following a decree of 342) duly completed.19

Sport, commerce, litigation, entertainment, and debate: the secular (and predominantly private-sector) emphasis is clear, and the other main building projects confirm this. We find increasingly ornate and gargantuan private tombs, which at times (as in the case of the famous Mausoleum at Halicarnassus) come almost, by a logical extension of private memorials into the public domain, to usurp the functions of temples. This, together with the progressive tendency toward the deification (or at any rate the worship) of human beings during their lifetime, was an inevitable development. Gigantism, though not yet reaching the heights it was later to scale under the patronage of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids (below, pp. 158, 164), is already noticeable during the fourth century, for example in the huge theaters now being constructed. The theater at Epidaurus could accommodate fourteen thousand spectators; the rebuilt Theater of Dionysus in Athens, by close-packing and banking the seats (only about sixteen inches’ width for each bottom), and by replacing all wooden supports with permanent stone blocks, increased its capacity to an amazing seventeen thousand.20

Stoas, or colonnades, originally attached, like covered cloisters, to temple enclosures, became increasingly secular and commercialized, often now containing shops, warehouses for grain storage, and similar features. The huge South Stoa in Corinth,21 facing on the agora, had two aisles and was no less than 525 feet long, with Doric columns outside (71 to the façade) and Ionic inside. It contained thirty-three shops, each with a storeroom behind it. Every shop was equipped with a deep well, drawing water from the fountain house of Pirene, itself enlarged and embellished at this time. Private edifices, such as the choregic monuments (319 B.C.) of Lysicrates and Thrasyllus in Athens22—the latter, significantly, adapted from the unfinished Propylaea on the Acropolis, a neat instance of the shift from civic to personal emphasis in building23—become, like the funerary stelae, extraordinarily elaborate and grandiose: as we have seen (p. 47), this trend was cut short only by Demetrius of Phaleron’s sumptuary laws (316/5). Sometimes the distinction between private and public monument is lost altogether. A classic instance is the circular tholos building at Olympia known as the Philippeion (begun by Philip II in 339, and completed after his death by Alexander),24 which contained gold-and-ivory statues of Amyntas III, his wife Eurydice, Olympias, Philip, and Alexander, executed by the great sculptor Leochares, and which seems to have been designed for ancestor worship in the manner of a Shinto shrine.

Private houses, too, became more luxurious. Already in the mid-fourth century Demosthenes felt impelled to complain, not only about municipal projects to clean up Athens, with improved street paving, whitewash, and new water fountains, but also that some get-rich-quick politicians had “built homes for themselves that were more impressive than public buildings”25—for a diehard city-state conservative, the ultimate act of hybris. Katagōgia, hotels, began to appear at the great cult centers such as Epidaurus.26 The Piraeus arsenal, built by Philo, the same architect who designed the façade for the Hall of the Mysteries at Eleusis, was over 433 feet long and nearly 59 feet wide, with a triglyph frieze and cornice, thirty-five columns down each side, and great doorways more than 9 feet wide by 16 feet high.27 This extraordinary edifice honored no god; indeed, no man: it was, rather, a storehouse for the rigging, sails, ropes, and other gear of the Athenian navy. Equally elaborate, and also stoa-like in appearance, were the shipsheds for the triremes themselves.28 As Roland Martin says, “A vigorous brand of functionalism, directed towards commercial ends, integrated itself with the purely religious and civic architecture which had been characteristic in the classical period.”29

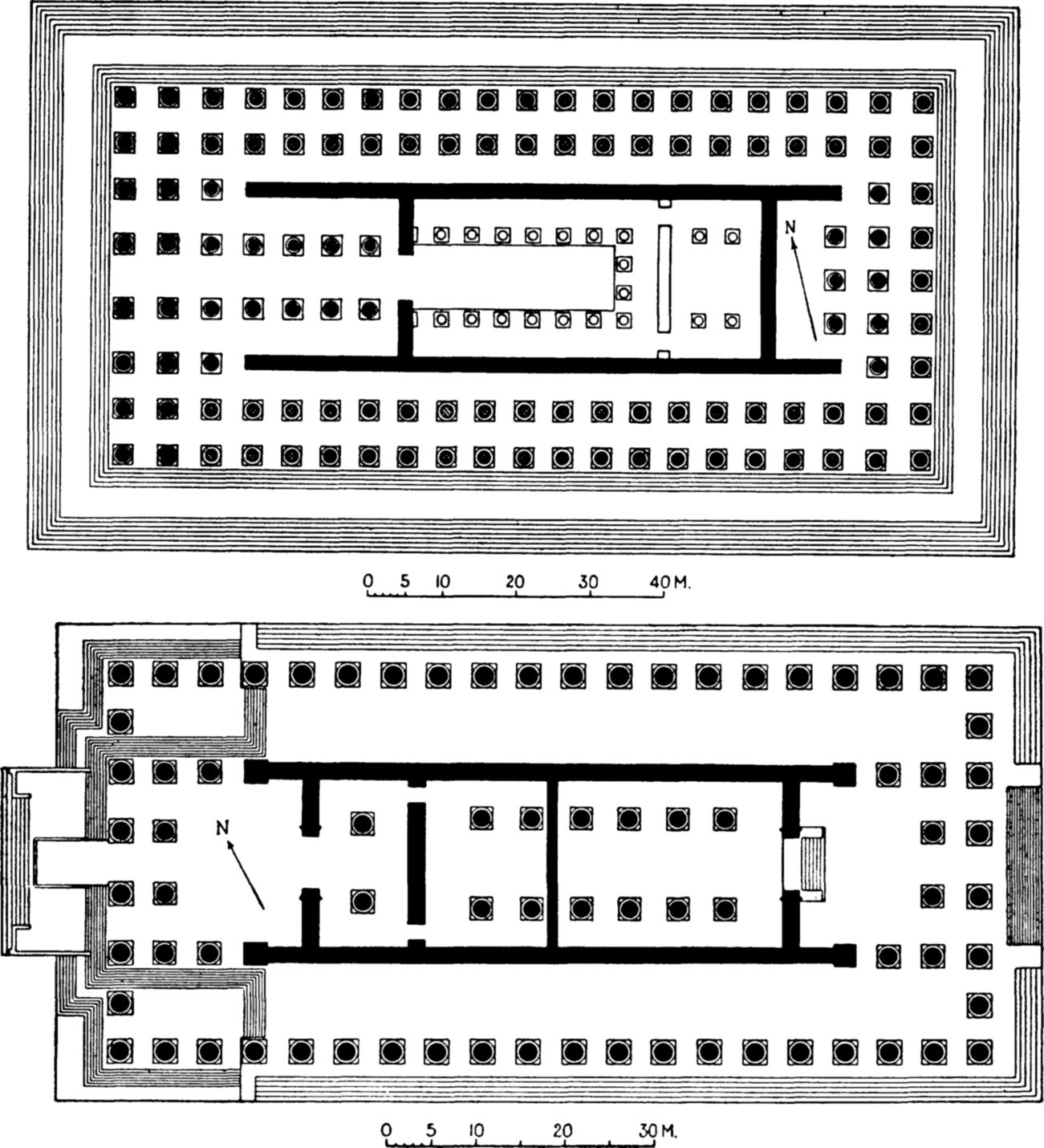

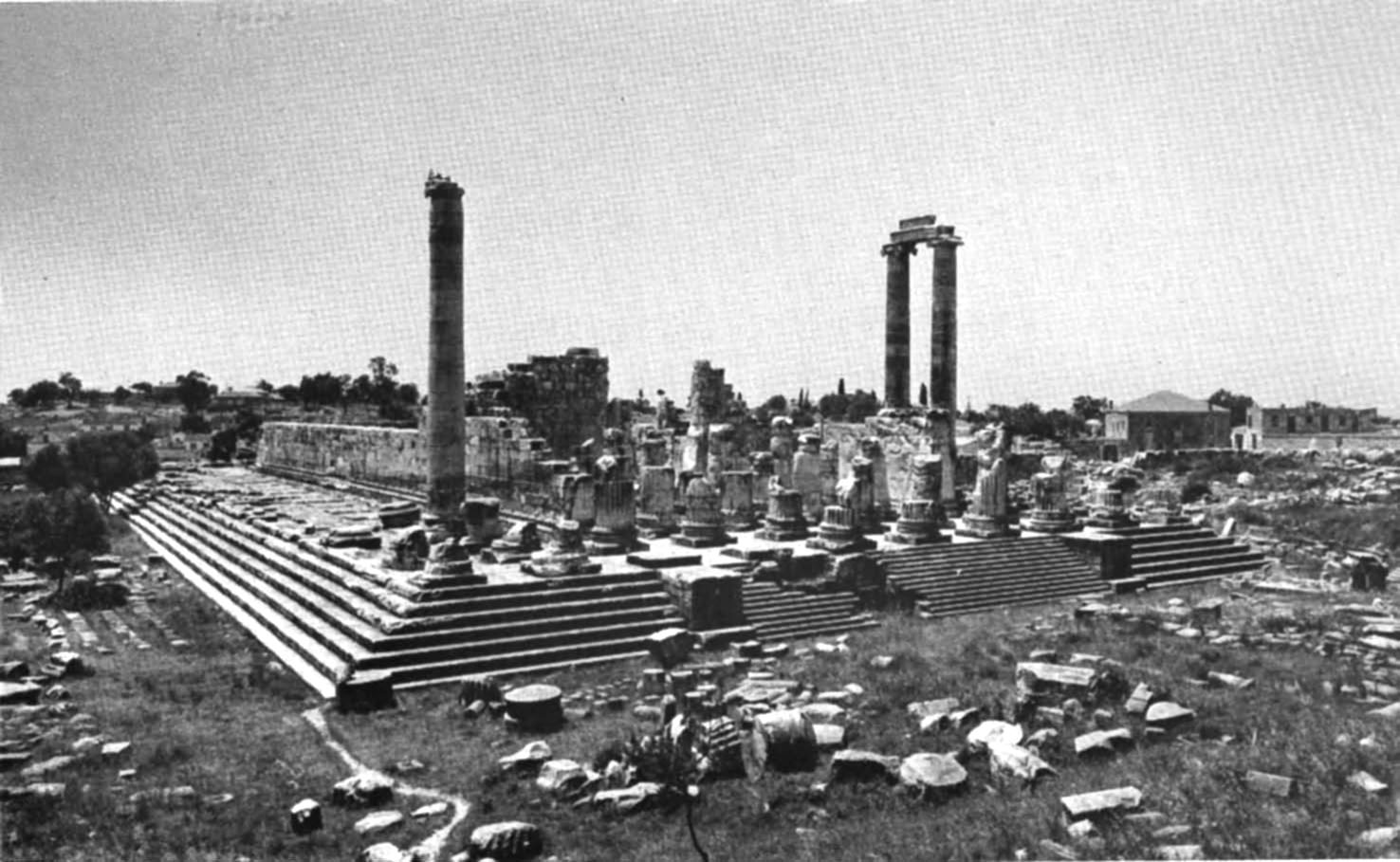

Temples, it is true, were still being built, but in prosperous Asia Minor rather than on the Greek mainland: in cities such as Ephesus, Sardis, Didyma, where there was still a powerful sense of continuity, mainly expressed in Ionic architecture, though Doric or Attic features began to creep in after a while. These temples, again, tended toward gigantism. One pleasant exception is the superbly sited temple of Athena Polias at Priene, begun about 340, designed by Pytheos, who later wrote a book on its architecture,30 and dedicated in 334 by Alexander himself; his dedicatory inscription still survives.31 More characteristic of the age were the huge temples of Artemis at Ephesus (built on an old base, but raised nearly 9 feet higher: volume was all) and at Sardis.32 Above all, there was the temple of Apollo at Didyma, an oracular shrine near Miletus. In 335 the temple had been in ruins for over a century, its shrine empty, the god’s archaic bronze image away in Ecbatana, looted by Xerxes as early as 494. But (miracle of miracles!) on Alexander’s whirlwind approach down the coast, the oracle was heard to speak again, proclaiming Alexander’s name.33 About 300 Seleucus recovered the image from Ecbatana, and began a new temple. Building on it continued sporadically until A.D. 41: even then it was still unfinished. It was so large, Strabo reports, that to roof it proved impossible; so the central cella was left open, an unpaved court planted with laurel, Apollo’s sacred tree, and containing a little Ionic shrine housing the god’s image and oracular spring. Such details remind us that Apollo was the Seleucids’ patron deity. There is a striking contrast here between the self-advertising art underwritten by a Seleucid monarch, and the back-water of nostalgia, commercialism, and private esthetics to which the old mainland city-states had retreated. The nearest thing to Didyma on the mainland was perhaps the temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, abandoned from Peisistratus’s day till the reign of Antiochus IV Epiphanes, and finally completed only by Hadrian.34

As a component of sculpture and painting the old classical reverence for order and geometric pattern still persisted; but it was increasingly undercut by the new realism, which preferred anatomical accuracy to organic harmony of structure, the world as it was, or appeared, rather than as it ought to be. The progressive loss of idealistic canons, combined with sophistic inroads on the old religion, brought divinities, already uncompromisingly anthropomorphic, down into the marketplace, where they rapidly became indistinguishable from market shoppers. The mid-fourth-century Piraeus Athena is as much society matron as goddess; the slightly later Artemis A (also from Piraeus) looks for all the world like a 1930s German film star, while with Artemis B (early third century) we have a clear case of individual, indeed, powerful, portraiture, a kind of Hellenistic Lady Bracknell.35

Heterosexuality, too, came into its own from the fourth century onward. Aphrodite was progressively stripped of her draperies, finally emerging nude in the famous statue made by Praxiteles, and bought by the city of Cnidos (after Cos had turned it down in favor of a more chastely traditional draped version). This statue—set in an open circular shrine, where it could be viewed from all sides—became a famous tourist attraction. Its appeal lay in qualities utterly remote from that earlier collective pride—compounded of athleticism, the warrior code, family loyalties, civic honor, and homosexual idealism—that underlay the great nude male statues of the archaic and classical eras.36 No accident, either, that the goddess who attracted this exposé was Aphrodite. The swing from public to private and personal preoccupations, combined with a post-Euripidean interest in the (often morbid) psychology of passion, made sex a subject of increasing interest as the Hellenistic age progressed. Among the mythological figures represented in Greek art from now on, on jewelry in particular, Eros and Aphrodite predominate. The market had been flooded with gold, taken by Alexander from the vast treasuries of Susa and Persepolis, and carelessly scattered as pay, largesse, and bribes. Much of it ended up adorning wives or mistresses in the shape of necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and pendants.

Menander’s obsession with affairs of the heart and the pursuit of profitable marriages is exactly matched by the record in the so-called minor or decorative arts, where a kind of overriding greed, sensuality blended with avarice, now becomes visible. Ours is by no means the first age to have suffered from what Thorstein Veblen, in his Theory of the Leisure Class, labeled “conspicuous consumption.” From the mid-fourth century—indeed, in many cases earlier—jewelry, clothing, luxury food, funerary monuments, entertainment, furniture, housing, all tell the same story: self-indulgence as a classic substitute for power. Though Demetrius of Phaleron’s sumptuary laws were no sort of real solution (above, p. 47), it is all too easy to understand the reason for their imposition. Always hovering on the very edge of ostentatious vulgarity, yet never quite succumbing, Hellenistic jewelry in particular—the stone of choice seems to have been the garnet—offers a unique blend of daring extravagance and dazzling technical skill. From Egypt came the Heracles knot, known there as an amulet since the second millennium B.C.; from Asia Minor, the crescent, sacred to the moon goddess, and adapted by Greek goldsmiths as a pendant; from the north, about 330, the hoop earring with an animal or human head.37 The conversion of religious motifs to secular use is symptomatic. Diadems, perhaps through association with the new royalty, became popular from about 300, and continued in vogue, complete with matching bracelets, for at least two centuries, going out of vogue when the Hellenistic monarchies were eclipsed by Rome.

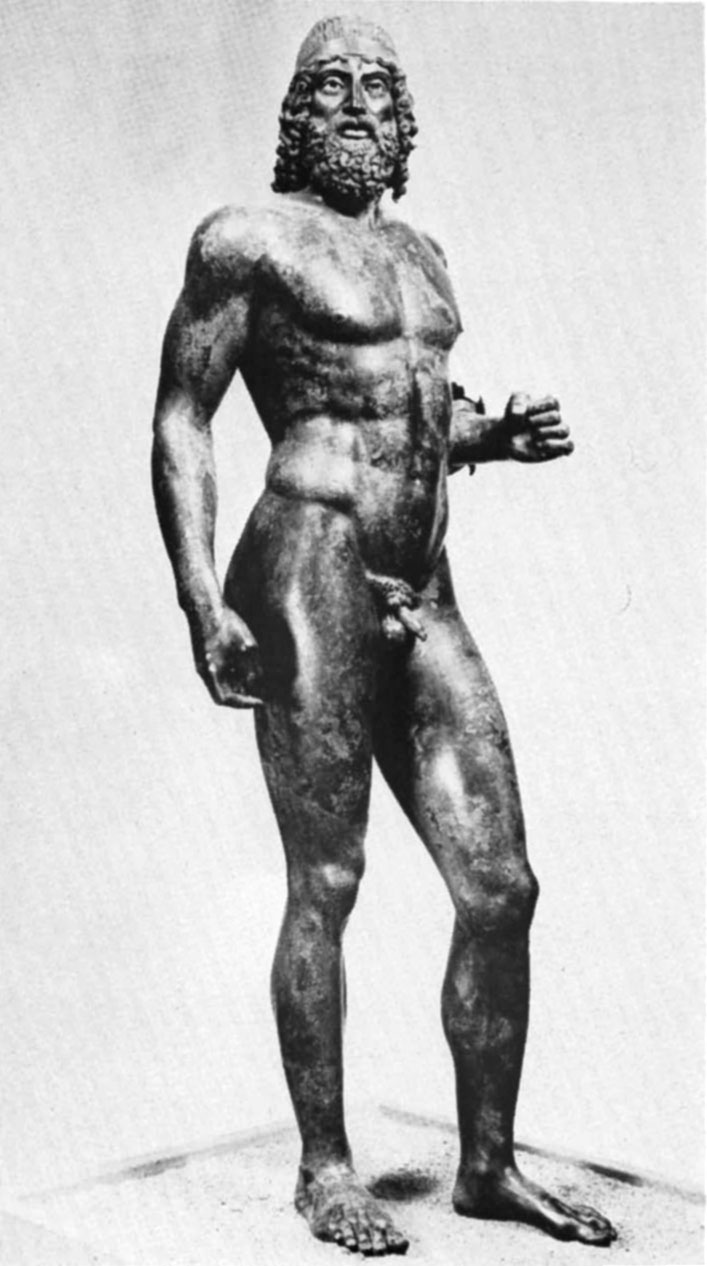

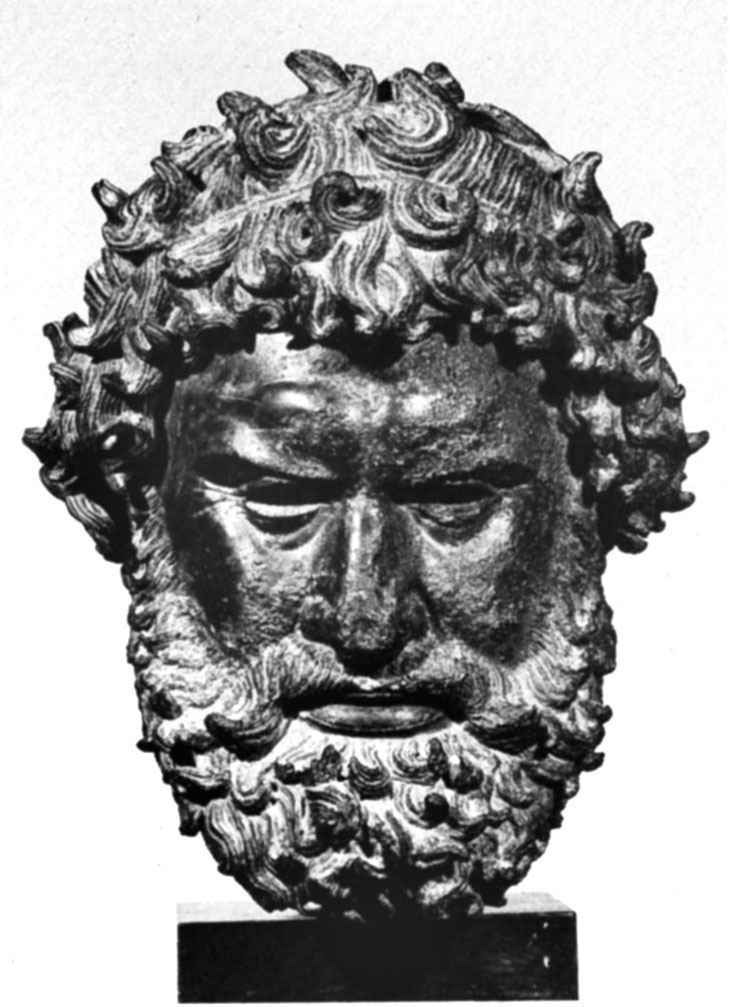

If the female statue shed its clothes (when appropriate) toward the end of the fourth century, the male nude became softened to a remarkable degree, in both bronze and marble: the feminine element is clearly emergent here too, and the concept of the hermaphrodite, increasingly prevalent from the early third century on,38 would seem its logical conclusion. In bronze especially, the young male statues from Marathon, Ephesus, and Antikythera, even the victorious athlete in the Getty collection, all reveal a mood of sensitive introspection that sets them in sharp contrast to the magnificent, bearded, heroic fifth-century warriors of Riace Marina, the embodiment of self-confident masculinity, with their heavy musculature and great, firm, rounded buttocks.39 But then the art favored by wealthy rentiers with the leisure for self-analysis and the cultivation of good taste—dependent, moreover, on hired mercenaries to do their fighting for them, their political activity limited to municipal affairs—is unlikely to bear much resemblance, whether physical or psychological, to that associated with the citizen-soldiers of a genuinely independent polis.

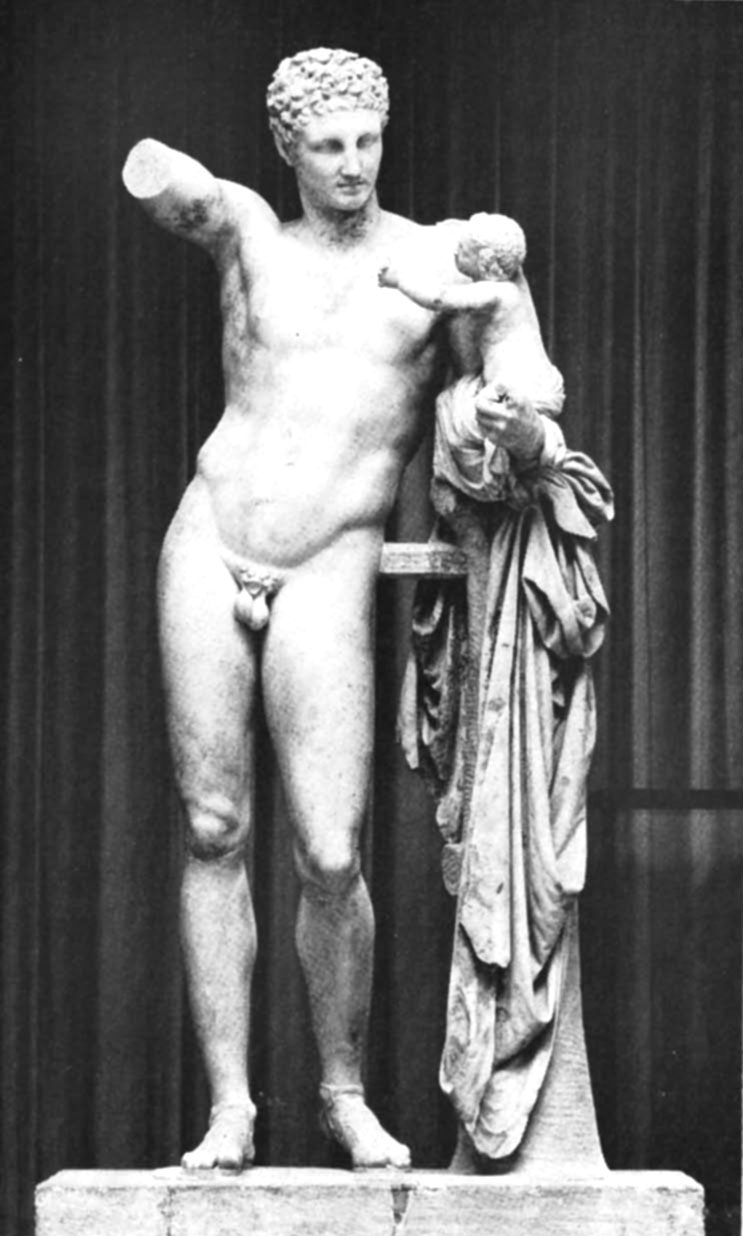

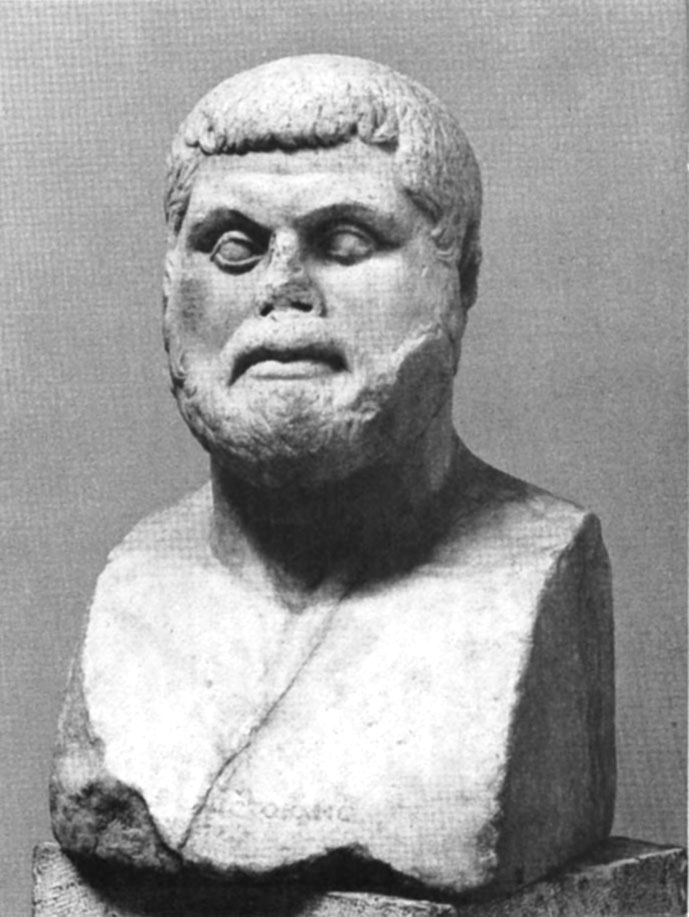

There was, however, another side, in late fourth-century sculpture, to this yearning, delicate, sensuous element—perhaps best expressed in Praxiteles’ famous group of Hermes with the Young Dionysus40—and that was a realism that set out to capture the roughness and brutality of everyday life. If Praxiteles was the begetter of the first genre, Lysippus (late fourth century) can surely be traced behind the second. “As the smooth, podgy loves and Venuses stem from the one, the muscle-bound, pin-headed bruisers are the other’s no less degenerate progeny.”41 Thirty years before, Silanion had made a still-idealized portrait of Plato; now, at Olympia, he set himself to tell the truth about a professional boxer,42 including “the characteristic marks that his career has left” (ca. 335).43

There was still idealism in portraiture, as the various heads of Alexander by Lysippus make plain; but Lysippus, too, was not only a traditionalist but also a great technical innovator, who, as Pliny says, preserved proportion (symmetria)44 while modifying “the squareness of the figure of old sculptors.”45 What, precisely, did this imply? If Lysippus pursued an ideal canon of proportions, wherein did his naturalism consist? A suggestive model is the design of the Parthenon, where subtle curves (entasis) were employed to give the appearance of verticality. Lysippus applied this principle to sculpture: he wanted his statues not only to be tall, but to look tall. Hence (as Pliny remarks) his reduction in the size of their heads. He also used torsion in such a way as to eliminate the foursquare flatness that had characterized earlier statues, producing a multiplanar composition that could be fully appreciated only by walking all round it. A good example of this is the so-called Apoxyomenos (“Youth Scraping Himself Off”)46—a nice instance, says one scholar, of how realistic an eye Lysippus had when kings and gods were not in question.47 We may also compare the Pothos (“yearning Desire”) by Scopas of Paros (? mid-fourth century), not only for its technique, but also for the skillful way it catches the half-sublimated eroticism that becomes such a characteristic feature of the Hellenistic period.48

This trend had begun at least half a century earlier. Leochares was not the only artist to portray Zeus as an eagle (ca. 370), carrying off Ganymede, but he may well have invented the motif,49 which recurs frequently in the minor arts. A bronze relief copy on the back of a folding mirror shows Ganymede clinging to the eagle in erotic ecstasy:50 whether this represents Leochares’ original intention it is impossible to determine, but the notion would be well in tune with the Zeitgeist. More suggestive still is Timotheus’s “Leda and the Swan”—another highly popular Hellenistic motif—in which the swan is scaled down to harmless domestic size, as though it were a pet goose, while Leda protects it with her robe against, once more, the attacking eagle (a nice reversal of the more common iconography, which has a huge swan towering over Leda in Olympian majesty);51 but then one sees the Beardsleyish double-entendre of the swan’s upstretched neck and head, which have been arranged so as to resemble a gigantic erect phallus.52

Equally interesting, though more for the light it sheds on ethical values than because of any direct psychological association, is the group of Eirene and Ploutos, Peace and Wealth allegorized, executed by Praxiteles’ father, Kephisodotos, between 372 and 368, and carrying clear associations with Aristophanes’ main theme in his Plutus.53 Once again we find a dominant Hellenistic motif prefigured in the early fourth century. Peace is now associated with wealth, profit, rather than with the prowess of victory (Nike): statues of Nike were still produced, but I do not consider it fortuitous that the most famous example, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, was possibly executed by a Rhodian sculptor, Pythokritos, at a time (early second century) when Rhodes was still a free and independent naval republic, and that Pythokritos executed at least one other, similar Nike on behalf of his own countrymen.54 The Rhodians, at least, were prepared to man their own ships, whereas a far more characteristic feature of the fourth and succeeding centuries was the professional mercenary soldier (see p. 74), hired by free citizens to do their fighting for them while they got on with their moneymaking and private erotic interests.

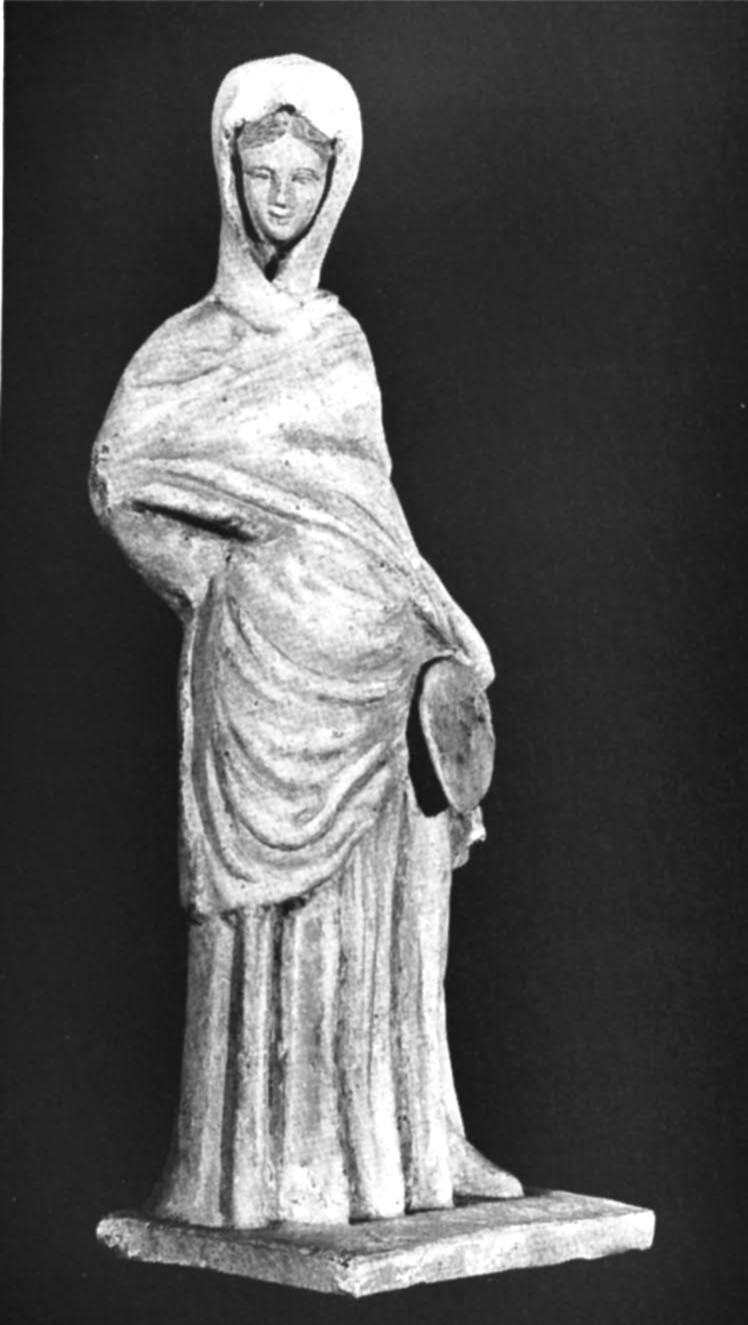

But naturalism, the determination to convey reality in both choice and treatment of subject, was the dominant mood; and where we can most easily study the fluctuations of this trend is in portraiture. Pliny notes that Myron, the mid-fifth-century sculptor, did not seem “to have given expression to the feelings of the mind” (animi sensus non expressisse).55 The lead seems to me to have come in painting, with Polygnotus’s search for ēthos. A generation or so later the psychological breakthrough was already well under way, not only in painting or sculpture (early portraits of Socrates are revealing from this viewpoint), but also in literature, as the late plays of Euripides make very clear.56 Xenophon gives a fascinating account of Socrates’ discussions with Parrhasios and Cleiton on the artist’s ability to reproduce not physical traits alone, but also the semblance of character (ēthos) and emotion (pathos)57—most notably, the visual arts suggest, suffering and pain. Here the painter had the advantage, it was felt, being able to portray both ēthos and pathos, whereas the sculptor was restricted to the latter.58 Yet here, still, we find the striving for idealization behind the realism. Sometimes the realism is generic, as in the famous Tanagra terra-cotta figurines, which look for all the world like miniature representations of the characters in Menander’s plays;59 more often we have reasonably firm ascriptions, and can identify the subjects portrayed.

We have to bear in mind that during the classical era “the erection of a portrait statue was the exception, not the rule.”60 The cult of personality was frowned on: when Pausanias, in 479, as captain general of the Hellenes put his own name on the base of the serpent column commemorating the Persian Wars, he provoked an international incident.61 Portraiture was for the gods; even if they were shown in human guise, that was no reason for men to climb up beside them. No fifth-century Greek, for instance, was ever represented on a coin. Obviously, with a shift in the public mood toward deifying (or otherwise enskying) human leaders, or, with Euhemerus (p. 55), explaining even the Olympian gods as, originally, heroes elevated to divine status, the barriers between gods and men were going to blur, and the boundaries of permissible iconography to grow wider, in both the public and the private domain. Nor was it only the great who demanded commemoration: the lost individual, too, would not be slow to fight the anonymity of megalopolis by having his own features shaped in stone to defy consuming time.62

Portraiture, with idealizing restrictions, had certainly existed in the fifth century, and perhaps even earlier: the famous Calf Bearer (ca. 570) offers a representation, if not the likeness, of the (named) dedicator.63 One interesting piece of evidence pointing in the same direction is the fact that the brothers Boupalos and Athenis, sculptors on Chios around 500, are said to have incurred the undying wrath of the satirist Hipponax by making a caricature of him in marble:64 the very idea of a caricature presupposes that of a likeness, the features of which can then be exaggerated or distorted. Pliny refers to a self-portrait by the sculptor Theodoros of Samos (fl. ca. 560–520).65 We have portrait busts of Themistocles and Pericles, both probably based on full-length originals made during their lifetimes.66 Demetrius of Alopeke (early fourth century) was well known for his individualized portraits, including one of a Corinthian general described by Lucian as bald, potbellied, and with varicose veins, and another of Lysimache, priestess of Athena and perhaps the model for Aristophanes’ Lysistrata.67 The urge to deny likenesses in this period has, I think, been overdone.

On the other hand, it is certainly true that the dawn of the fourth century reveals a new attitude. The barriers between mortal and immortal were breaking down. Grateful cities, as we have seen, were quite ready to worship Lysander as a god, just as Asclepius the healer could now be portrayed as human, sympathetic, accessible.68 By the time of Alexander’s death the urge for realism and individualism had created circumstances in which portraiture could flourish. It has often been pointed out how loath most of the early Successors were to portray themselves on coins.69 Lysimachus, for instance, despite his consuming ambitions (p. 28), was still using the legitimizing portrait of Alexander at the time of his death. Pyrrhus, similarly, never used his own image on his coins. It is significant that not until the time of Philip V and Perseus was royal portraiture used on coins circulating in the cities of mainland Greece. The prejudice against Macedonian overlordship ran deep, and was long-lasting. Yet there is a difference between overt and covert self-promotion, and the Macedonians, to look no farther, had done a good deal of the latter. An ostensible Zeus can look very like Philip II (or, earlier, Amyntas); an ostensible Heracles is, beyond any doubt, Alexander. The earlier Argeads show remarkable facial individualism in their supposed portrayals of deities.70

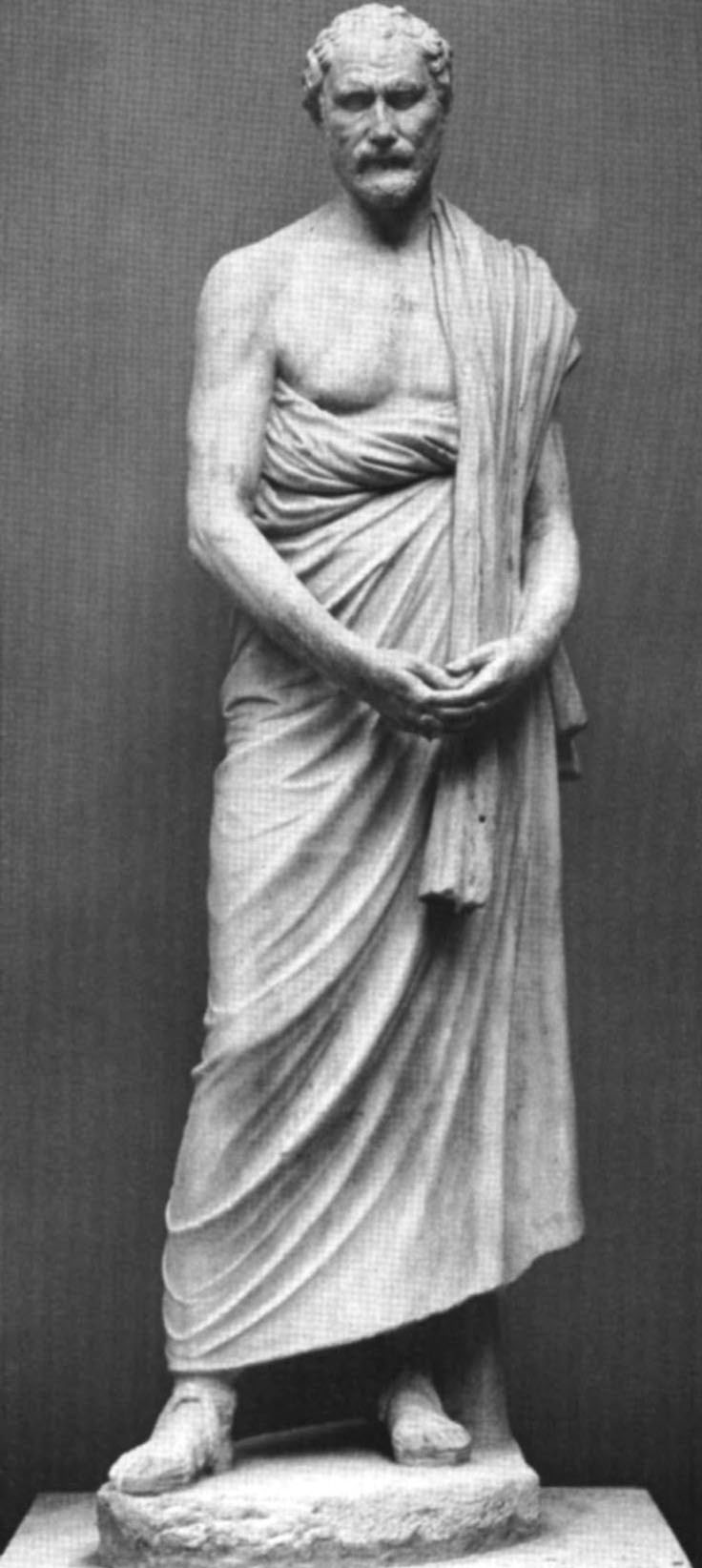

Philip, we remember, had not been above having his image carried in procession, a thirteenth god, along with the twelve Olympians.71 (He was assassinated the same day: serve him right for impiety, said traditionalists.) There was also the matter of that circular family shrine at Olympia (above, p. 96), with all its gold-and-ivory portrait statues—a medium hitherto reserved for cult figures. New discoveries of ivory miniatures in the royal Macedonian tombs at Vergina suggest, again, a well-developed tradition of realistic portraiture by the closing decades of the fourth century.72 Yet the sheer diversity of Alexander’s likenesses73—even though they duly record the upward glance, the twist of the neck, the supposed pothos—cannot encourage us in the hope that any of the alleged portraits we possess are what today we would think of as a true representation. The official monopoly granted to Lysippus was no guarantee of verisimilitude. If I hazard a guess that the Issus mosaic comes closest to the truth, that is no more than a subjective impression, partly inspired by the matching portrait of Darius and the generally realistic detail of the picture. Features that can be caricatured seem, paradoxically, most likely to survive without serious distortion. Ptolemy I’s hooknose and cracker jaw at once carry conviction.74 On the other hand, the portraits we have of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides are in all likelihood those commissioned by Lycurgus long after their deaths, and copies at that.75 Both the Demosthenes and the Aristotle best known to us are posthumous, and the Demosthenes, like most of our surviving portraits, is also a late Roman copy. Both offer marvelous appreciations of temperament and character; but are they likenesses in the modern sense? Many scholars doubt it.76 Yet, obstinately, a sense of individualism persists.

When we turn to painting, we are confronted with one unfortunate but incontrovertible fact: though the period covered by this chapter was held in antiquity to mark the apogee of this medium,77 very little of the original work has survived, so that scholars are too often reduced to arguing retrospectively from what may, or may not, be accurate Roman copies, reinforced by the testimony of hit or miss literary sources such as the elder Pliny. A good deal has been inferred from painting on pottery, but this is chancy. During the fourth century, red-figure conventions were progressively abandoned in pursuit of greater depth and realism. Yet the quest for spatial freedom never broke away from an essentially linear technique until red-figure ran its course (by 320 in Attica; a couple of decades later in Italy). It remained throughout a conservative medium, its moves toward modernization always cautious in the extreme.78

Till comparatively recent times evidence of what the great mural and panel painters had achieved in this period was, to say the least, inadequate. There was the Alexander Issus mosaic, probably copied from a lost fourth-century mural by Philoxenos of Eretria. There were marginally relevant and ill-preserved tomb paintings from Etruria and Kazanlak and Alexandria. There were those late Roman copies and adaptations; but what, precisely, had they been copied from? During the past half-century, however, the excavation of a number of Macedonian tombs, some containing well-preserved murals, has shed steadily more light on the nature of Hellenistic painting, and done much to confirm both its classically based conservatism and its now-undoubted links with the Romano-Campanian tradition. The tomb of Lyson and Callicles (third or second century) reveals an illusionist style of architectural painting that looks forward to the so-called Roman Second Style. The impressionist brushwork of the portrait of Rhadamanthys in the Great Tomb at Lefkadia (ca. 280 B.C.) anticipates that in the “Satyr and Maenad,” a painting of Nero’s reign in the House of the Epigrams at Pompeii, just as its composition suggests the wall paintings of Boscoreale (first century). The Tomb of the Palmettes, also at Lefkadia (late third century) has yielded marvelous complex floral patterns that, again, belong in a tradition dating back to the fourth-century painter Pausias and continuing through the Pompeian period.

But the most remarkable discovery came in November 1977, when Manolis Andronikos opened up two royal Macedonian tombs at Vergina (ancient Aigai) with fourth-century frescoes: a hunting scene, a portrait of a mourning woman in the Polygnotan tradition, above all, a splendidly vigorous mural showing Pluto’s rape of Persephone, with Persephone desperately stretching out her arms to her agonized companion Cyane as the god’s chariot whirls her away. The hunting scene, over-hopefully attributed, by some, to the original artist of the Issus mosaic,79 was in bad condition when excavated, and has since suffered further deterioration; but the other two are excellently preserved. Since then, in 1981, the excavation by Andronikos of three more tombs at Vergina has provided further striking proof of continuity between the early Hellenistic tradition and that known to us from Pompeii, as the full-length portrait of a young warrior from the second of these tombs (early third century) demonstrates.80

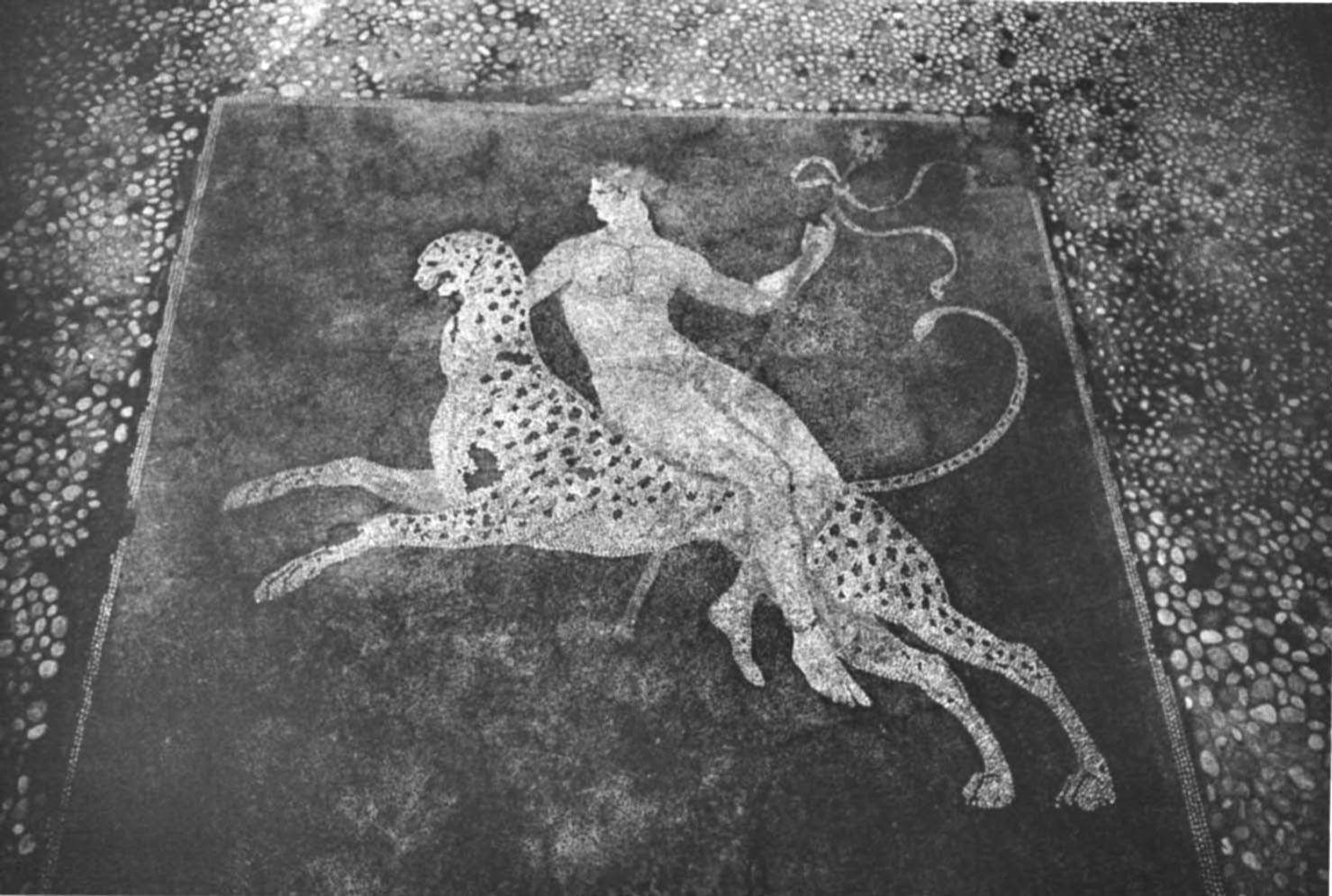

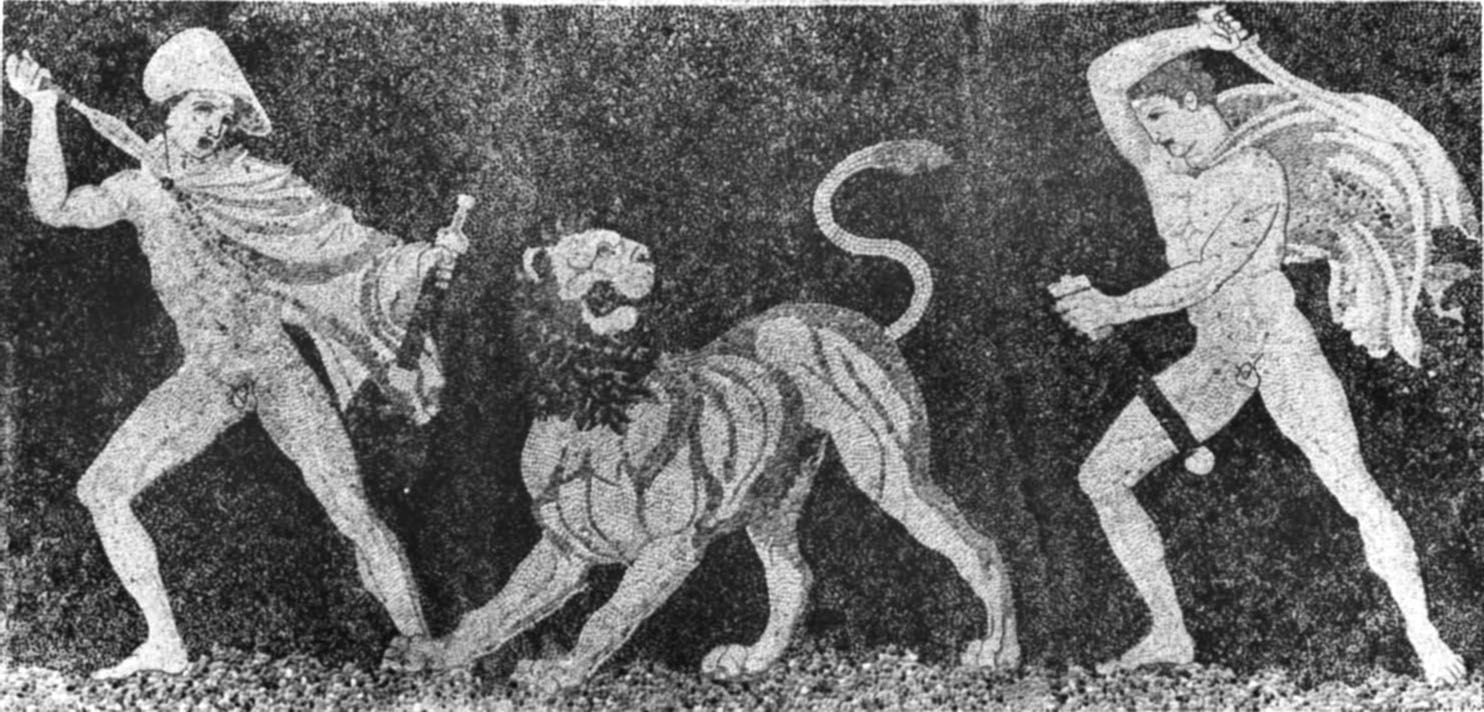

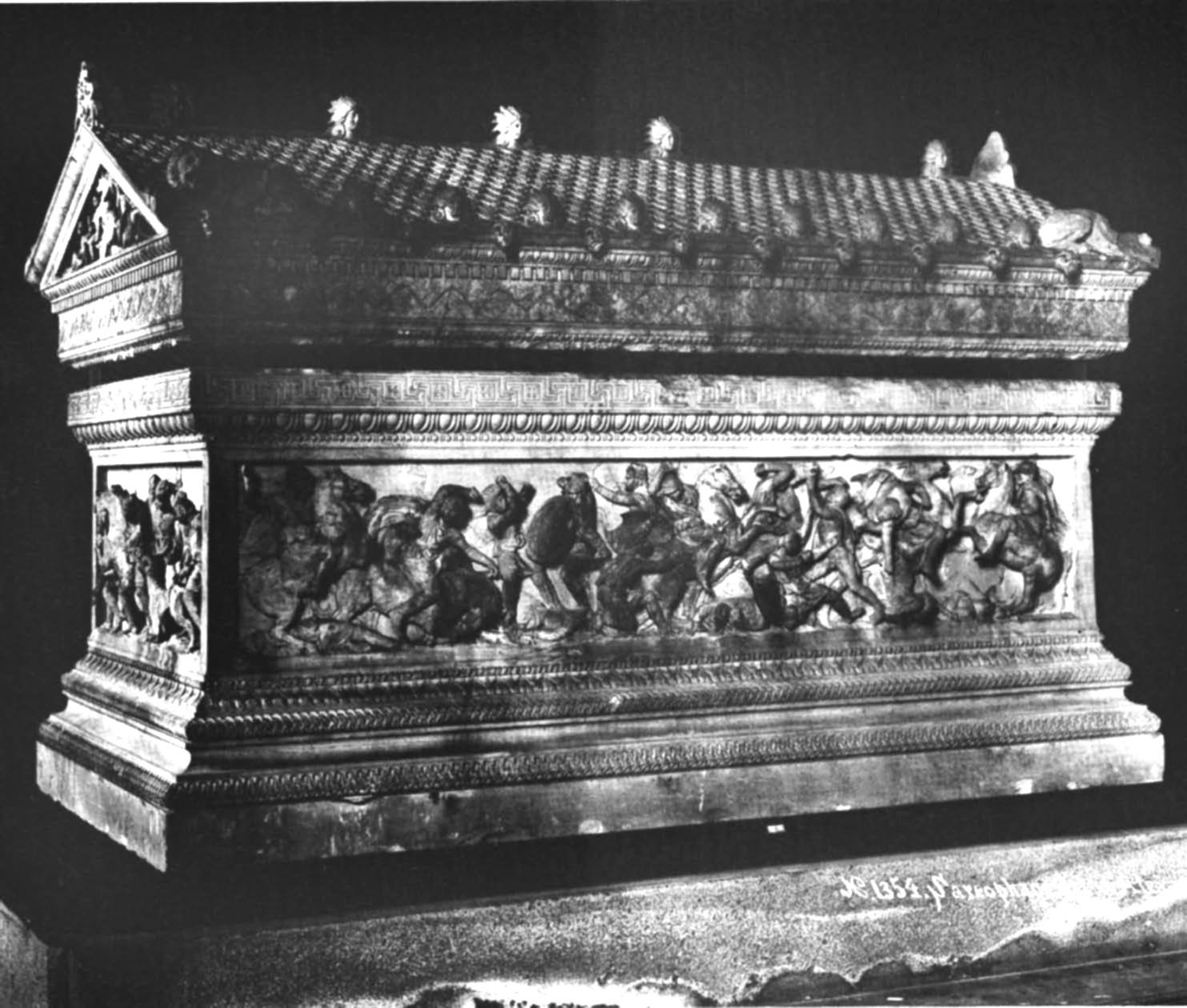

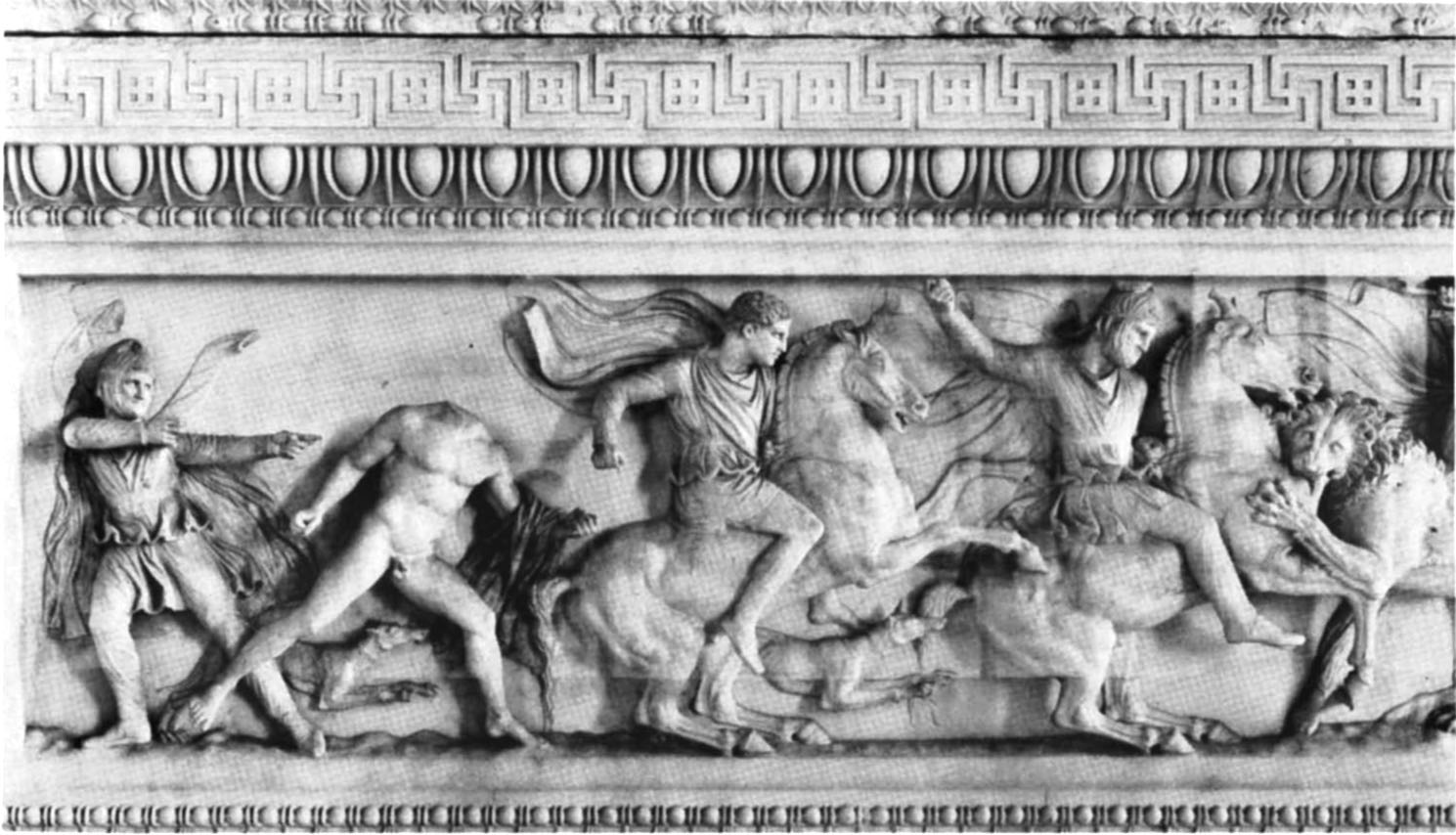

There is a clear link here, too, with the fine mosaics from the royal Macedonian palace at Pella,81 and all belong to the category of court art, which assumes so important a role later in Alexandria and Pergamon. Mosaic work, by its very nature, was always an art that catered to the wealthy and powerful. From the first quarter of the fourth century onwards (as we know from examples at Olynthus and Eretria as well as Pella) it displays a fashionable, and recurrent, iconography: griffins, sphinxes, panthers, Nereids, Dionysiac motifs.82 We may note that the Pella mosaics are made with natural pebbles, black, white, or colored, whereas the use of tiny cut cubes (tesserae) seems not to have been introduced until sometime after Alexander’s conquests. (Where the technique originated is still uncertain: competing theories argue for Sicily, the East, or Greece itself.) We also find marble chips being used (e.g., at Olynthus before 348), or irregular stone fragments, or several of these in combination.83 Pella’s lion-hunt mosaic matches the fresco adorning Philip’s tomb at Vergina: both look forward to the relief work on the so-called Alexander Sarcophagus from Sidon.84

We are reminded that from now on it was, primarily, monarchs who had both the urge and the resources to celebrate their own achievements, who were ready to exploit art or architecture in any way that would effectively promote the royal message.85 Those compelled to live under such regimes—especially those who remembered a different way of life—found different solutions. For the most part, as we have seen, they turned inward for their freedom, or to the world of private and sensual pleasure for their escape from involvement: the world of Eros and Aphrodite in all its manifold enticements;86 or, at a lower level, an epicure’s obsession with haute cuisine,87 which was responsible for good cooks’ fetching such high prices in the Hellenistic age, and for the endless lip-licking allusions to food in the comedians. Intoxication (methē) was also allegorized, and by no means in a hostile manner.88

Zeuxis experimented with chiaroscuro early in the fourth century, while his contemporary Parrhasios was achieving unprecedented subtlety and expression of line.89 The latter painted a picture of the Athenian dēmos that Pliny, rightly, calls “an ingenious subject-piece,” since Parrhasios portrayed the Athenian people as, at one and the same time, inconstant, unjust, bad-tempered, merciful, compassionate, open to persuasion, vainglorious, proud, humble, fierce, and cowardly, a description with which few historians would quarrel, but that must have taxed even Parrhasios’s resources.90 Perspective, first discovered in the fifth century by Agatharchus, was steadily refined.91 Perhaps the most significant innovation, apart from portraiture, was the discovery of landscape painting, a precise romantic analogue in the visual arts to the urban passion for piping shepherds and bucolic peace. The painters who portrayed, as Vitruvius says, “harbors, headlands, woods, hills, and the wanderings of Odysseus,”92 scenes of sunny pastoral escapism, were catering to precisely the same déraciné audience of city intellectuals as a poet like Theocritus (see p. 235), writing idylls on the rivalries of rural goatherds. Escapism and realism were now two sides of the same coin. Menander had done no more than foreshadow a general trend. What politically conscious artist of the fifth century could ever have brought himself to paint a still life, that hymn to things-in-themselves, that total and delectable rejection of all social awareness? (It is clear that Hellenistic artists did paint still lifes: unfortunately, only Roman copies or variations survive, though even these are striking enough.) When I try to summarize the private vision of the Hellenistic era, a still life or a genre scene—a marine-life mosaic, a bowl of fruit, a hare—is what instantly flashes into my mind. But as Louis MacNeice well knew, “even a still life is alive,” so that “the appalling unrest of the soul / Exudes from the dried fish and the brown jug and the bowl.”93 Zeuxis and Chardin inhabited uncomfortably similar worlds.94