The third century B.C. witnesses the acme of Hellenistic culture, just as the fifth witnessed that of the classical era; yet both, paradoxically, are very short, during their most crucial years, on solid historical documentation, and for once the later period is worse off than the earlier.1 We have no continuous narrative of events except for Justin’s miserable (but at times, alas, indispensable) epitome of Trogus Pompeius, a Gaulish historian who wrote under Augustus: it takes Justin to make us properly appreciate Diodorus, lost, except for fragments, after Ipsus (301). Trogus‘s own work was derived, at third or fourth hand, from the lost history of Phylarchus, who picked up where Duris of Samos (281) and Hieronymus of Cardia (Pyrrhus’s death in 272?) left off, and carried the story through to Cleomenes III’s defeat at Sellasia (222). If Hieronymus had a bias in favor of the Antigonids, whom he served,2 Phylarchus seems to have been a puritan idealist with a strong distaste for Hellenistic luxury, and a corresponding romantic admiration for the last bastions of Greek city-state individualism, above all for the Sparta of Agis IV and Cleomenes III.3 This made him critical of the Achaean League’s statesman Aratus of Sicyon (below, p. 151), and brought down on his head, in consequence, some of Polybius’s most rancorous and partisan disapproval.4 Plutarch, on the other hand, who idolized the free polis, identified its demise with that of Demosthenes, and disliked Hellenistic kings, and their courts, to the point of not writing about them (an omission the modern historian can only regret),5 found Aratus and Phylarchus equally attractive writers, a fact that has created some nice problems in source criticism.

Phylarchus survives in Plutarch’s Lives of Pyrrhus (reinforced by Pyrrhus’s own memoirs), of the Spartan kings Agis IV and Cleomenes III, and of Aratus of Sicyon. Aratus also left memoirs, which, again, Plutarch used in his biography. Since Aratus and Cleomenes, as we shall see, pursued directly conflicting policies, and since Plutarch’s criteria are moral rather than historical, the Achaean leader’s pact with Antigonus Doson against Sparta (below, p. 259) provoked Plutarch to charge him, more in sorrow than in anger, with moral inconsistency. How could any good man oppose those who sought to bring back the disciplinary virtues of the Spartan ancien régime?6 The historical digressions in Pausanias and Strabo are also in all likelihood ultimately derived from the same sources.7 It is only from 220 that we once more have a contemporary narrative voice, and key witness, in Polybius, who also devotes an important digression to the origins of the Achaean League.8 Polybius is by no means an impartial witness, but remains notwithstanding a full and eloquent one, whose firsthand experiences as statesman and soldier stood him in good stead as a historian (below, pp. 273 ff.). The papyri and inscriptions provide much help in dark places, but all too often of a local (and, in Egypt, parochial) nature: minor honors, village tax returns, details of municipal government that can only with difficulty be fitted into any overall pattern.9 Coins are useful as a guide to regal propaganda; in the case of the Indo-Bactrian kings (pp. 330 ff.) they provide almost our only evidence.10

Thus the history of the period, from Corupedion (281) to the accession of Philip V in Macedonia (221), has to be patched together from shreds and snippets: much of it, especially the chronology, remains problematic to a degree. Yet to qualify every statement becomes tedious and, ultimately, self-defeating. If, then, the following narrative on occasion sounds a good deal more assured than the facts warrant, the reader should bear in mind throughout that the evidence is shaky, and the hypotheses remain fragile.

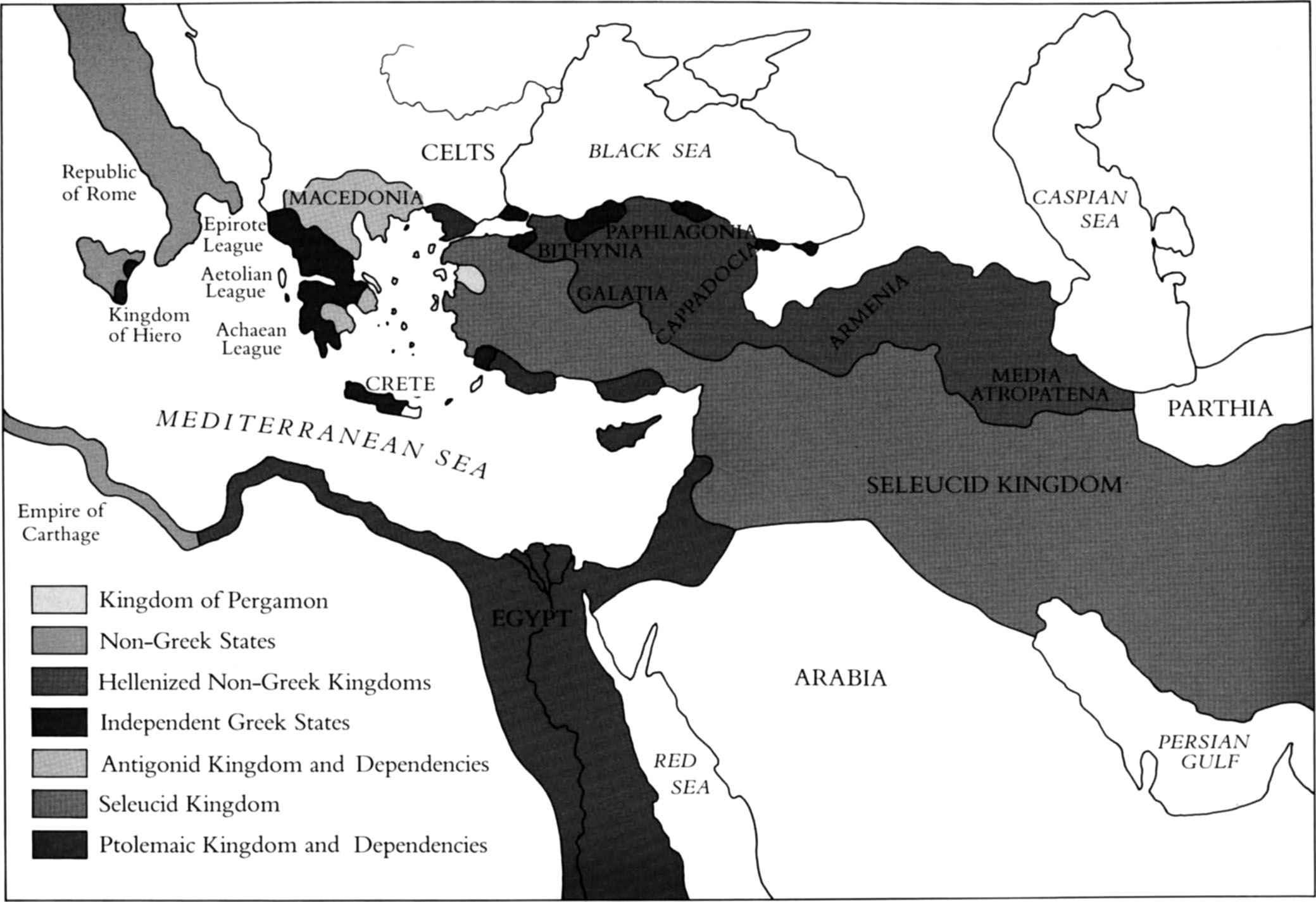

The period with which this chapter is concerned, up to Antigonus Gonatas’s death, in 239, reveals a round of frontier wars between the three major dynasties—Antigonids, Seleucids, Ptolemies—in which, as usual, “each side supported the enemies or revolted subjects of the other.”11 Antiochus I, Seleucus Nicator’s son, by now over forty, was chiefly concerned with holding his vast, heterogeneous eastern kingdom together, and seeking to prevent (generally without success) a whole string of internal secessions, from Pergamon in the west to Bactria in the far east.12 Though his official Eastern capital was Seleucia-on-Tigris, his focus of interest tended toward the Mediterranean, as his concern for Antioch and its great port, Seleucia-in-Pieria, makes very clear. He expended far more effort and investment on Asia Minor and the always elusive foothold in Europe than he did on his vast Oriental satrapies, and this in the long run was to prove a major factor in the collapse of the Seleucid empire. Ptolemy Philadelphos, in Egypt, was, like his father, a defensive counter-puncher rather than an aggressor, a trait he passed on to subsequent generations:13 no accident that after Actium, in 31 B.C., the Ptolemaic domains were still almost exactly what they had been when defined at Babylon and Triparadeisos. A series of Syrian wars emphasized the obvious friction that was bound to exist between Ptolemies and Seleucids; they also hinted at Ptolemaic interest in controlling the trade routes of Asia Minor, the eastern Mediterranean, and the Aegean.14 This last concern probably lay behind the Ptolemies’ perennial diplomatic meddling in the affairs of mainland Greece, their unswerving hostility to Macedonia, and their readiness to support any anti-Macedonian faction, from Pyrrhus to the Achaean League.

Antigonus Gonatas, on the other hand, was largely concerned to secure Macedonia’s frontiers and to establish some kind of status quo, a measure of political and economic stability, after long years during which the country had been stripped of its manpower and its resources, a no-man’s-land fought over by a succession of savagely ambitious warlords. But such an aim required firm control of the Greek mainland, and hopes of independence were by no means yet dead in the city-states. First Athens made a bid for freedom in the so-called Chremonidean War (268?–263/2?: below, pp. 147 ff.); then came the rise of the Achaean League under the leadership of Aratus of Sicyon (from 251/0: pp. 151 ff.). Later, as we shall see (pp. 258 ff.), Sparta—aggressively independent, even in reduced circumstances, and now straining to recover old glories, virtues, and privileges by way of what passed for social revolution—made a fierce bid to smash the power of Macedonia in Greece once and for all, a bid that was destroyed at Sellasia (July 222: see p. 261).

The establishment, development, and organization of the Achaean and Aetolian Leagues present interesting features: they are, first and foremost, almost the only successful examples of Greek federation as a working political device. This involved, inter alia, the concept of sympoliteia, a division of authority within the federal structure, between local and central government, the latter being responsible for such key areas as foreign policy, military affairs, and court cases involving treason. A citizen of any member state might be restricted to his own city in the exercise of political rights, but would enjoy civil privileges throughout the federation. Another significant feature of the system, particularly in the case of Achaea, was the admission of non-ethnics on equal terms, essential if the sympoliteia was to develop strongly: as we shall see, this policy led to Achaean confrontations with Sparta and, later, with Rome. Though some sort of Achaean confederacy had been in existence during the fourth century, the true development of the League can be dated to 280, when the first four cities federated, and, more particularly, to 251 (see below, p. 151), when Aratus brought Sicyon in as a member, and himself very soon became the leading Achaean statesman. The Aetolians had federated as early as 370, probably in response to the expansionist activities of Thebes.15 During the third century the organization of both Leagues was along roughly similar lines: an annually elected general (stratēgos), a council (boulē, synedrion), and an assembly (ekklēsia), together with a smaller steering committee (dēmiourgoi, apoklētoi), which dealt with much of the day-to-day work. The Aetolian League was more chary than the Achaean about granting full membership to peripheral poleis, and always kept firm control over their activities, in many cases offering them isopoliteia, reciprocal rights without unification, rather than sympoliteia. Since brigandage and piracy formed a regular line item in its budget, the Aetolian League’s guarantee of asylia, freedom from reprisals or seizure of property, was highly valued.

Meanwhile separatism of a different sort was in evidence in Asia Minor. The powerful fief of Pergamon, which, under its governor Philetairos, had transferred its allegiance from Lysimachus to the Seleucids after Corupedion, was soon to break away altogether, as an independent kingdom (p. 148). About the same time a string of cities along the southern shore of the Black Sea, including Byzantium, Chalcedon, and Heracleia Pontica, declared their independence and formed themselves into a “Northern League.”16 Bithynia and Cappadocia became autonomous states under native dynasties. The tendency of the Seleucid domains to fragment was there from the very beginning. One last curious enclave in Anatolia was that occupied by the Gauls—or Galatians, as they were generally known to the Greeks of Asia from now on—who, after their various defeats, had been pushed off by Antiochus I and his war elephants into a kind of reserve in Phrygia (275/4),17 from where they could be drawn on at need as mercenaries by the various contending parties. Their uncouth violence and migrational mass descent had thoroughly scared the Greeks:18 it followed that one sure badge of ascension in the battle of Hellenistic power seekers was a good, clean, certified victory over these peripatetic bogeymen. Antigonus Gonatas, Antiochus I, the Aetolian League, even Attalus I of Pergamon (p. 150), all acquired such a certificate, to their immense advantage.

Let us first consider the position of Antigonus Gonatas, that most unlikely of Macedonian monarchs: short, snub-nosed, knock-kneed, earnest patron of intellectuals, a Stoic with a taste for the worship of Pan, and a ruler whose concept of his duties (similar in this to that other Stoic, Marcus Aurelius) verged on the masochistic.19 In 276, largely as the result of his victory the previous year over a Galatian horde outside Lysimacheia (p. 134), he was reestablished as king of Macedonia. He had a nonaggression pact with Antiochus I, whose half-sister (and stepdaughter) Phila he now married (276), an alliance that was to last throughout his long reign.20 The wedding hymn, composed by Aratus of Soli, celebrated the rout of the Gauls by Pan’s divine agency, but could not, of course, fail to shed a little glory on the bridegroom also, as Pan’s human avatar.21

Antigonus now set up his court—a notably intellectual one—in Pella.22 Having spent a good deal of his career as a king without a kingdom, he had been forced to seek his strength internally, to the lasting benefit of his own character; and here, clearly, his early training under Zeno of Citium was invaluable. The influence of Stoicism at Antigonus’s court was strong, indeed fundamental. Zeno himself refused an invitation to go there, but he sent his disciple Persaeus instead, to tutor Antigonus’s son, Demetrius, and to provide the proper theoretical backing for Antigonid kingship.23 It is a mark of Stoic involvement—unique among Hellenistic thinkers—in affairs of state at a practical level that Persaeus should have died defending Corinth on Antigonus’s behalf against Aratus (243).24 Antigonus’s notion of kingship as “noble servitude” undoubtedly stems from his Stoic attachments,25 though it has a Cynic tinge to it as well: kingship brought suffering rather than pleasure; the diadem, Antigonus declared, was a bauble that most men would never so much as retrieve from the midden if they knew all that it entailed.26

Among the writers and thinkers at Antigonus’s court the best-known undoubtedly was Aratus of Soli, author of the Phaenomena (see p. 184), an astronomical poem that presents Zeus as the consciousness of the world, as reason personified, a development of Anaxagorean Nous, the agent and instrument of cosmic order. As goes the god, so should the king go. The stars in their courses serve mankind (navigational aids, the agricultural year cycle); the supreme being sees to the good of his creatures. No accident that Aratus was the nearest thing to a scientist in Pella, or that his science was primarily moral in its application. The true Stoic was not interested in pure science (p. 634); such banausic matters, he felt, could be left to the hedonists and moral imbeciles who thronged to Ptolemy’s antechambers in Alexandria. Pella was now a serious, dedicated court—though not above Hellenistic-style flattery of its ruler’s virtuous achievements: Aratus wrote an encomium of Antigonus as well as his wedding hymn, and it was the king’s old teacher Menedemus who moved the honorific decree on his behalf after that first famous victory over the Gauls.27 Self-complacency is an endemic hazard of virtuous living.

In addition to Aratus, Pella provided a base for the distinguished historian Hieronymus of Cardia (p. 137), who had served Gonatas’s father and grandfather before him as officer and garrison commander, and now in his old age wrote for the Antigonids—therefore, inevitably, both stressing and favoring their actions—the history of the Successors’ wars.28 There was also that plain, blunt Cynic philosopher, Bion of Borysthenes: caustic, vulgar, arrogant, exhibitionistic, perhaps an ex-slave, yet also tenderhearted, appalled at the notion of a god who could visit the sins of the father on the children, ready to take pity even on a tortured frog—this last evincing a disposition most uncharacteristic in any Greek, ancient or modern.29 He scoffed at religion, was fond of boys, gave popular public lectures (for a stiff fee), and seems to have enjoyed the role of licensed philosophical buffoon at Antigonus’s court. (“Why tear your hair out in bereavement?” he asked. “Sorrow isn’t cured by baldness.”)30 He and Zeno’s disciple Persaeus both hint at that strain of radicalism, on occasion leading to something very like social revolution, that tended to show up where Stoic or Cynic advisers were in evidence. (Cleomenes III of Sparta was another Stoic, guided by the philosopher Sphaerus; and he, as we shall see [pp. 257 ff.], planned just such a revolution—though for highly suspect motives—and came very close to bringing it off.) If a man demands justice, not merely as an abstract concept, but in setting up the life of a society, and if he holds, further, that within that society (however defined) all men have equal rights, then the odds are that his views, sooner rather than later, are going to set something or someone on fire.

Antigonus Gonatas, then, may fairly be called the first Stoic king. Unlike the Ptolemies and some others, he never sought divinization, whether for self-aggrandizement or as an instrument of political propaganda. Macedonia was not a receptive country for ventures of that sort. Philip II’s attempt to present himself as a thirteenth god in the Olympian pantheon had not proved auspicious,31 and Alexander’s request for deification had met with a scandalized refusal from Antipater.32 Gonatas modestly argued that he lacked the charisma for such a step, and, considering the number of times he was defeated, he may well have been right. Even after 276 his position remained questionable so long as Pyrrhus was still alive.

In late 275 Pyrrhus at last returned from Italy (see pp. 228 ff.), and early the next year invaded Macedonia.33 His primary objective was loot: he had 8,500 men in his army, and no money with which to support them. But at the same time it is plain that he was making a genuine bid to recover the throne. He also bore a personal grudge against Antigonus, who had refused him support during his war with Rome. His forces engaged those of Gonatas in the passes of Aoös, near Antigoneia. When, after a stubborn rearguard action, Gonatas’s mercenaries were defeated, his demoralized Macedonian troops went over to Pyrrhus en masse. Gonatas himself had no choice but to flee, accompanied only by a small cavalry escort, to the safety of Thessalonike. Pyrrhus now recovered most of Macedonia and Thessaly (274), leaving Antigonus only one or two coastal cities and a still-powerful fleet. To Pyrrhus’s chagrin, his defeated opponent still maintained the royal purple: like his father before him, Gonatas did not equate loss of territory with loss of kingship, even after a second drubbing in the field, this time at the hands of Pyrrhus’s son Ptolemaeus.34

Pyrrhus could now, briefly, claim to be king of Macedon once more: the Macedonians had shown whom, in the moment of victory, they preferred. But the preference was fleeting. Pyrrhus lost popularity by letting his Gauls plunder the royal tombs at Aigai,35 and by leaving his son Ptolemaeus to hold Macedonia on his behalf while he plunged into a pointless, and finally fatal, campaign in southern Greece. Early in 272, on the invitation of that disgruntled royal Spartan exile, Cleonymus (see p. 223), Pyrrhus invaded the Peloponnese,36 his excuse being that he aimed to liberate all cities still held by Antigonus’s garrisons. Athens, always eager to support any anti-Macedonian power—the occupation of Piraeus still rankled—offered him alliance, for what that was worth.37 A stubborn defense by Sparta bogged Pyrrhus down,38 and Antigonus took the opportunity to recapture most of Macedonia.39 He then took his fleet down to Corinth (summer 272), and marched on Argos. Those of the Argives who preferred Pyrrhus to Antigonus sent an urgent message to the Epirot for help.40

Pyrrhus promptly raised the siege of Sparta and came north. Both armies seem to have been let into the town by different factions.41 During the street fighting that ensued, Pyrrhus was knocked unconscious by a tile an old woman lobbed at him from a rooftop. An enemy soldier, seeing who he was, hacked off his head as he lay there, and sent it to Antigonus, who—like Alexander with Darius, or Caesar with Pompey—professed shock and sorrow, but must also have felt considerable relief.42 This was in the autumn of 272: resistance to Gonatas collapsed instantly, and this time for good. He might have won all Greece now, but, like Ptolemy, he preferred limited gains: he was, first and foremost, king of Macedonia.43 He still held Piraeus; on his way back to Macedonia he garrisoned Eretria and Chalcis. Henceforth his rule was virtually undisputed in Macedonia, though, as in Philip II’s day, there was to be vigorous opposition, not only from Athens and Sparta, but also, now, from the Aetolian and Achaean Leagues: his support for tyrannoi did not endear him to would-be democrats. But so long as Antigonus held Acrocorinth, Piraeus, and the key cities between central Greece and the north, his position was hard to shake. Athens, despite her approaches to Pyrrhus, he treated with courtesy, and respect for her culture; it would not be all that long before propertied moderates were offering him official sacrifices (245/4), and stelai were erected commemorating his victory over the Gauls.44 But the last word was with his Macedonian garrison in Piraeus, and Athenians still chafed under that alien restraint.45 It was, ironically, Ptolemaic Egypt that gave them the illusory chance for another bid to regain their freedom.

The reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphos (283–246) almost exactly coincided with that of Antigonus Gonatas (276–239). During the same period we find two successive kings in Seleucid Asia: Antiochus I Soter (281–261), and Antiochus II Theos (261–246). The period thus possesses a certain unity,46 underlined by the consistency throughout it of Ptolemaic policy. At home this policy was one of cultural ostentation and self-advertisement, by way of such things as the Museum and Library (above, pp. 84 ff.), even the Pharos (p. 158). It was in 279/8 that the indefatigable Arsinoë, bored with sanctuary on Samothrace, finally returned to Egypt. Here she cultivated her brother, Ptolemy II, her junior by eight years, to such effect that he repudiated his existing wife—another Arsinoë, and, to confuse matters further, the returned Arsinoë’s former stepdaughter—on a charge of conspiracy, exiled her, and then proceeded to marry his own full sister. She promptly adopted his first wife’s children, took the title “Philadelphos,” and began to appear with her brother-cum-husband on his gold and silver coinage.47 The date of this marriage is uncertain: all we know is that it must have taken place before 274/3, when Arsinoë appears as regnant queen on the Pithom stele.48

Arsinoë was undeniably beautiful as well as determined, and the mass of honorific material that has survived suggests that Ptolemy’s incestuous marriage was something more than a mere act of calculated policy. At the same time, calculation undoubtedly entered into it. Ptolemy I had already been deified, and the more divinity that hedged the royal succession the better. Ptolemy II probably figured on playing Osiris to Arsinoë’s Isis for the benefit of his Egyptian subjects, and Zeus to her Hera for any Greeks who, like the scurrilous poet Sotades (above, p. 82), were unwise enough to query the propriety of the relationship.49 Sailors were already praying to Arsinoë during her lifetime, a sign that she was regarded in some sense as the avatar of Isis, and she was promptly deified after her death (July 270). Though there is no reason to doubt her influence over Ptolemy, her role as the political power behind the throne has probably been exaggerated: historiography is no more immune than any other discipline to the insistent claims of feminism.50 We need not suppose, for example, that the First Syrian War (274/3–271), against Antiochus I, was won only by her energy and brains:51 Ptolemy could be a forceful enough ruler when force was called for.

In his foreign policy economic as well as political considerations applied. Ptolemy wanted control over the Aegean, the eastern Mediterranean trade routes, and the sea passage through to the Black Sea, and seems to have profited by the death of Seleucus to strengthen his position in these areas.52 He already, as early as 279/8, had a bridgehead at Miletus.53 Despite a revolt in the buffer state of Cyrenaica, engineered by his half-brother Magas,54 Ptolemy by 272/1 had won back the best part of coastal Syria and large parts of southern Anatolia, some as far west as Caria, and including most of Cilicia. His devoted court poet Theocritus (pp. 235 ff.) celebrated these conquests in his Encomium of Ptolemy:55

Over all [Egypt] Lord Ptolemy rules as king: in additionThat sail the seas are his, all the sea and landSwarm horsemen and shieldmen, agleam in brazen armor.

He also put out feelers to the West with an embassy to Rome:56 trade beyond the Straits of Messina would be, from now on, increasingly dependent on Rome’s good will.

Ptolemy’s hopes of establishing long-term control over the Aegean were not encouraged, however, by the resurgence of Macedonia under Antigonus Gonatas. Ever since the days of Philip II, Greece and the Aegean had been Macedonia’s natural sphere of influence, and Gonatas showed no signs of abandoning that role. In particular, once firmly in power he seems to have worked hard to restore the naval supremacy that Macedonia had enjoyed under his father, Demetrius.57 To Alexandria, nothing could have looked more potentially alarming. It followed that for years the Ptolemies actively subsidized all Macedonia’s enemies in this area. After Pyrrhus’s death (272) Ptolemy concentrated his efforts on Athens. He was already supplying a large proportion of the city’s wheat.58 He also knew just how to exploit Athenian longings for freedom and autonomy. The dream of regaining effective control of Piraeus was hard to resist.59 Potential anti-Macedonian allies—including the Spartan king Areus, ever ready to switch sides in furtherance of his inflated royal ambitions—were carefully nursed into a coalition. When he judged the time ripe, Ptolemy, through his agents, encouraged the Athenian nationalists to throw out the pro-Macedonian party,60 and, a little later, assured of Egyptian support, and backed by a variety of Peloponnesian allies, to declare war on Antigonus (autumn 268?).61

The ringingly patriotic motion for war was made by an idealistic, and handsome, Athenian citizen, Chremonides, who not only gave his name to the war,62 but also—like Antigonus, like Cleomenes—was a professed Stoic, a student of Zeno’s. Thus we have the piquant situation of a war being fought out between the philosopher’s former disciples, though in neither case, it would seem, on Stoic principles:63 Antigonus meant to consolidate his power, while Athens was in pursuit of that ever-receding polis dream, genuine self-determination—a goal conditional, in the first instance, upon the recovery of Piraeus.64 There was much talk of a new crusade against the barbarian, of Greek freedom, of Sparta and Athens fighting side by side (with the help of an Egyptian fleet, but this was not stressed). Ptolemy, so the Chremonidean Decree claimed, “conspicuously shows his zeal for the common freedom of the Greeks”: in fact he was doing no more than exploit that old and potent slogan with a view to limiting Antigonid naval expansion—both strategic and economic—in the Aegean,65 and the substantive help he gave the Athenians was minimal. It is, nevertheless, significant how many Greek cities were ready to throw their weight against Macedonian domination.

There was inconclusive campaigning during 266, to which Antigonus Gonatas’s possession of Corinth remained the strategic key. Then, in 265, Antigonus met the ambitious Spartan king Areus outside Corinth and left him dead on the battlefield.66 Despite ineffectual diversionary tactics by his opponents, Antigonus now put Athens under siege. Ptolemy had other claims on his attention just then: perhaps because he had won control of Ephesus (ca. 262/1), Antigonus’s powerful fleet was now threatening his position in the Aegean, and indeed soon scored a major victory over the Ptolemaic squadrons off Cos (261?).67 Thus the Egyptian fleet did not break Antigonus’s blockade, and Ptolemy, who had instigated the rising, did nothing, just as his father had done nothing, to save Athens.68 Once again the city was starved into surrender (262/1?). This time there was no polite talk about autonomy. Antigonus put his own Macedonian officials in to run the city.69 Piraeus kept its garrison (the precise role, and effectiveness, of which during the siege remains uncertain); the Hill of the Muses was reoccupied. Troops were also posted at strategic points along the coast of Attica.70 Athens lost the right to appoint her own magistrates (and possibly to mint her own coins),71 becoming

a mere university cityAnd the goddess born of the foamAnd the philosopher narrowed his focus, confinedHis efforts to putting his own soul in orderAnd keeping a quiet mind.

Antigonus Gonatas was now “the undisputed master of Greece.”72

While all this had been going on, Antiochus I in Asia had had his own problems—mostly, as always, those of secession. Not only was the Seleucids’ control over their outlying dependencies uncertain, but at the same time they took no firm steps to limit or rationalize their frontiers. Pontus, Bithynia, and Cappadocia were all now either independent of, or breaking away from, the unwieldy eastern empire. The satrapies of Bactria and Sogdiana were soon to achieve independence en bloc (ca. 250: see p. 332). The movement that ultimately led to the secessionist kingdom of Parthia was already under way in 247, when Parthia was invaded by Parsa tribesmen under their leader Arsaces (hence the Arsacid dynasty). Thus Antiochus’s famous proclamation, “I am Antiochus, the Great King, the legitimate king, the king of the world, king of Babylon, king of all countries. . . . May I personally conquer [all] the countries from sunrise to sunset, gather their tribute, and bring it [home],”73 has a certain ironic ring to it in 268. With the death five years later of Philetairos, the elderly, possibly eunuch, governor of Pergamon, Antiochus found himself faced with trouble much nearer home.74 Philetairos’s nephew and adopted son, Eumenes, decided to make his own bid for independence. Antiochus sent out a punitive expedition against him, and Eumenes defeated it near Sardis.75 Another fragment of empire was ready to break loose.

Then, in June 261, Antiochus himself died, at the age of sixty-four.76 He was succeeded by his son Antiochus II Theos, co-regent since 266, when he had replaced is elder brother, Seleucus, executed on suspicion of disaffection.77 The new king was reputedly an alcoholic and a playboy,78 but he had enough political sense to seek a concordat (homonoia) with Macedonia. Antigonus Gonatas welcomed this new support. If he wanted to drive Ptolemy out of the Aegean he would need an even stronger fleet; and now, with a general peace giving all contestants a much-needed breathing space, he set about building it.79 Undercover agitation continued in the background: Cyrene was once more maneuvered into revolt, and Ptolemy only recovered it in about 246. With Macedonia’s tacit support, Antiochus II launched yet another campaign against various Ptolemaic outposts of empire, the so-called Second Syrian War.80 Our information concerning this war remains minimal. Antigonus may also have had trouble on his northern frontier,81 and in any case he was faced with a crisis much nearer home: his nephew Alexander, governor of Corinth and Chalcis, rebelled against him (253/2), possibly with Egyptian backing, and proclaimed himself king (252? 249?).82 Ptolemy seems to have lost ground in Cilicia, Pamphylia, and Ionia—where Antiochus II regained Ephesus (ca. 258), and picked up the sobriquet of Theos (“God”) after his liberation of Miletus.83 In 253 the king of Egypt was hard-enough pressed to make his peace with Antiochus, through that favorite Ptolemaic device, a dynastic alliance. Antiochus married Ptolemy’s daughter, Berenice Syra, who brought him “a vast dowry,” arguably the revenues of Coele-Syria.84

In order to make this match Antiochus II had been obliged to repudiate his prior wife, Laodice, turning over considerable domains to her at the same time.85 Remarriage was always risky for a Hellenistic ruler, and the douceurs with which Antiochus tried to buy Laodice off had singularly little effect. However, both parties to the arrangement died shortly afterwards, Ptolemy II in January 246, and Antiochus II that same August. Antiochus died, apparently from illness but, some said, as the result of poisoning, at Ephesus, where Laodice happened to be in residence.86 The scene was now set for a new showdown, between two ambitious queen mothers, Laodice and Berenice Syra, each competing on behalf of a potentially regnant son. It also seems likely that two rival foreign policies, Laodice’s of competitive independence and Berenice’s of cooperative alliance, also lay behind the hostilities that now followed.87

Laodice’s son Seleucus had, so she claimed, been designated heir by Antiochus on his deathbed. However, Berenice had also borne the late king a son, and meant to enforce the child’s claim as sole legitimate successor after Laodice’s repudiation. From Antioch she appealed to her brother in Alexandria, the new king Ptolemy III Euergetes (“Benefactor”). Ptolemy at once left for Antioch, only to find when he got there that both Berenice and her child had already been assassinated, probably by Laodice’s agents, if not, as one source suggests, by Seleucus in person.88 The Third Syrian (or Laodicean) War, which resulted from these events, dragged on until 241, with Seleucus—now Seleucus II Kallinikos (“Gloriously Triumphant”)—campaigning in Asia Minor and Syria,89 and Ptolemy grandiloquently claiming victories from the Hellespont to the Euphrates.90 He did briefly occupy Antioch (246–244). Perhaps in 246/5 he also fought a naval battle off Andros, though the evidence is highly ambiguous;91 he appears to have lost it, which will have done little to restore his much-diminished role in the Aegean, and even less to assuage his political and economic problems in Egypt itself. The peace certainly extended his northern frontier in Syria, leaving him with one first-class prize, Seleucia-in-Pieria, the port of Antioch, which remained in Lagid hands till the time of Antiochus the Great;92 but many of his other claims seem to have been ephemeral or exaggerated. Seleucus II had his own problems. His mother, Laodice, had insisted on his giving co-regency, together with the territory north of the Taurus Mountains, to his younger brother, Antiochus Hierax (“the Hawk”). With typical Seleucid aplomb, the Hawk—who did not, any more than Ptolemy Keraunos, acquire his title by accident—lost no time in setting himself up as an independent sovereign.93 What with provincial rebellions and internecine dynastic rivalries, the unwieldy Seleucid empire was to prove itself fatally susceptible to fission.

In that same year Eumenes of Pergamon died (241), to be succeeded by his adopted son, Attalus I.94 The most interesting thing about Eumenes was perhaps his support (indiscriminate, if we can trust Diogenes Laertius) for the philosophical schools of Athens—an indication that the Pergamene dynasty, even at this early stage, envisaged itself as the patron and preserver of Greek culture.95 Attalus seems to have decided that a victory over the Galatians, still the uncontrollable scourge of Asia Minor, was, as always, the best and quickest way to win solid international prestige. He duly met and defeated them in a pitched battle: only after this success (237?) did he formally lay claim to the title of king (as well as that of Savior, Sōtēr), which his predecessor, although de facto monarch, had always carefully avoided.96

Also in 241 Antigonus Gonatas, now the elder statesman of Greece (and indeed known, like that not-dissimilar character Konrad Adenauer, as “the Old Man”),97 was forced to make an unsatisfactory peace with the newly powerful Achaean League (pp. 139–40). Though his rebellious nephew, Alexander (above, p. 149), had died in 246/5, it was not until the winter of 245, and then in somewhat bizarre circumstances, that Gonatas had recovered the fortress of Acrocorinth,98 and even then he did not hold it for long. Two years later, in 243, Aratus of Sicyon, the Achaean League’s powerful and dynamic general, who had brought Sicyon (freed by him in 251 from a brief but violent tyranny) into the League,”99 now had also wrested Corinth once more from Antigonus’s control, thus establishing the Achaean Confederacy as a major force in Greek affairs.100 Corinth, though garrisoned on its acropolis by four hundred Achaean troops (not to mention no less than fifty watchdogs), for the first time since Philip II’s day held its own city keys, and joined the Achaean League on a voluntary basis. Megara, Troezen, and Epidaurus followed suit, so that League territory now had a common boundary with Attica.101

Antigonus, who earlier in Aratus’s career had hoped to patronize him or turn him into a subservient tyrannos,102 saw, too late, the caliber of the man he was up against. Something of a vendetta followed. With the Achaean League, inevitably, getting support from Egypt, Antigonus had no option but to turn to their rivals the Aetolians (243/2), thus incurring a good deal of moral opprobrium from those, Polybius included, who regarded the Aetolians, with good reason,103 as little better than opportunistic condottieri and pirates.104 However, Polybius’s claim that these unlikely allies planned an invasion of the Peloponnese, with the partition of Achaea as its objective, has been disproved by modern research.105 The Achaean League made an alliance with Sparta, and also, hopefully, appointed Ptolemy III the League’s honorary admiral (242).106 The Aetolian assault was driven back by Aratus,107 and Antigonus, his support gone, found himself with no option but to negotiate 241/0).108 Corinth remained independent; all that Macedonia still held in the Peloponnese were the cities of Argos and Megalopolis. Meanwhile Aratus kept busy. He planned the assassination of the tyrant of Argos, and, when that failed, made an abortive raid on the city (240?).109 More interestingly, having moved in on Attica, he now “in his zeal to liberate the Athenians” tried to assault Piraeus,110 for which he was censured by the Achaeans, since the armistice with Macedonia had already been ratified (242). Afterwards, in his memoirs, he blamed a subordinate for the attack. This earned him the scorn of Plutarch, who tells us that Aratus made many other unsuccessful assaults on Piraeus, “like an unlucky lover.”111 It is worth noting that Athens did not join the League, but chose to remain neutral.

But perhaps the most significant result of this abortive conflict involved Sparta. The twenty-odd years after the death of Areus (265) form an obscure period in Spartan history. His son and successor, Acrotatus, was killed in battle outside Megalopolis (260), and there seem to have been other reverses. But now a young and active Eurypontid king, Agis IV, had taken the field with Aratus. During the four years of his reign (244/3–241) he had, for reasons we will consider later (p. 250), proposed a whole series of drastic social reforms, including the two time-honored steps of debt cancellation and redistribution of land. These proposals, though they could be justified in terms of the ancient Lycurgan constitution, and were probably essential if Sparta was to reemerge as a major Hellenic power, aroused intense opposition among a wealthy minority into whose hands the larger part of the land of Sparta had fallen. These found their natural leader in Leonidas II, the Agiad king whom Agis had deposed (on extremely flimsy grounds), exiled, and replaced with Cleombrotos, Leonidas’s son-in-law but a supporter of Agis. Leonidas’s unforgivable act had been that of persuading the Spartan council of elders (gerousia) to reject Agis’s reformist proposals. One constitutional illegality begets another. Successive boards of ephors challenged and repudiated each other’s acts, with increasing violence. Finally, during Agis’s absence at the Isthmus, Leonidas and his group seized power; and when Agis came back, he was put through a travesty of a trial, and then summarily executed.112 That, however, was by no means the end of his reforms.

What Antigonus Gonatas made of these developments it is hard to tell. His Stoic training must have given him a certain sympathy with the aims of the Achaean League and of men like Agis: he certainly went out of his way to try to conciliate Aratus, though Aratus himself was notably cool toward Agis, whom he saw, with reason, as a threat to stability in the Peloponnese. But politically, in the last resort, Gonatas stood on the other side, against all radical or ideological reform: he was an Antigonid first, a philosopher second. However, his dilemma, if dilemma there was, did not last long. Early in 239 Antigonus Gonatas died, at the ripe old age of eighty. His real achievement was to have lasted so long, to have given Macedonia a chance to recuperate from the years of anarchy, to build up some economic reserves once more. His son, who succeeded him as Demetrius II, was a tough and ambitious prince, and, unlike Gonatas, by no means content with the status quo.