With both Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz in his hands, Wellington could feel more secure as he began to plan his thrust into Spain. There were two options open to him: an advance south into Estremadura against the army of Marshal Soult, or a move east against Marshal Marmont commanding the Army of Portugal in central Spain. A move against Soult would certainly be the more appealing as far as the Spaniards were concerned. After all, the Supreme Junta of Spain had long since been in Cadiz and it would not take too much effort to relieve the city. From a military standpoint, however, it offered few advantages. Advancing south would simply prompt Soult into moving north where he would easily be able to join forces with either Marmont or Suchet, who was occupied on the eastern coast of Spain. An advance against Marmont, on the other hand, would represent a serious threat to French communications with France. This move would probably induce the French to bring more forces to support Marmont but Wellington planned to prevent this with a number of counter-measures. Spanish guerrillas were employed to prevent French units from concentrating, diversionary tactics were used on the eastern coast to distract those French forces, while in Andalucia the Spanish commander Ballasteros was ordered to make preparations for an offensive from the south to keep Soult occupied. Elsewhere in the Peninsula, from the Mediterranean to the Bay of Biscay, Spanish guerrillas and Portuguese militia were given orders to harry and hustle the French whenever possible.

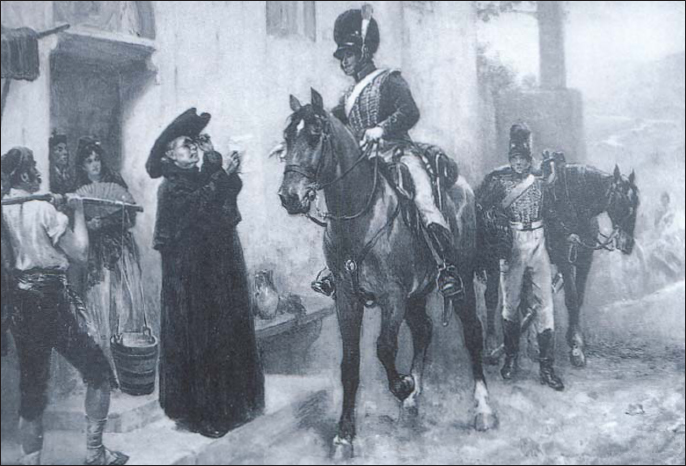

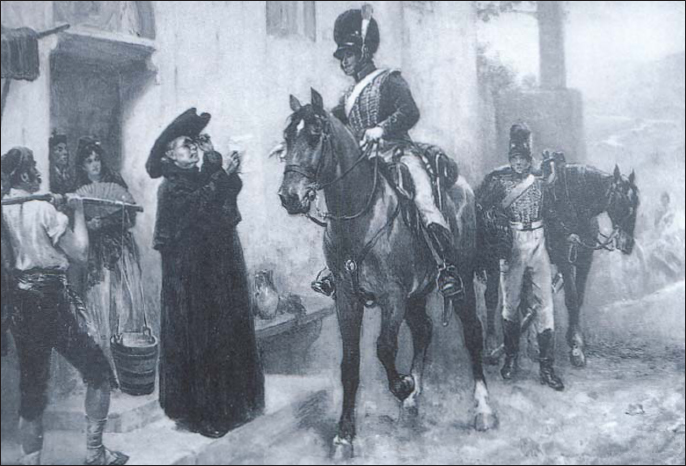

British cavalry on patrol in the Peninsula. The Allies enjoyed the advantage of having the local population, and in particular the clergy, on their side in the Peninsula, both of whom were a great source of intelligence.

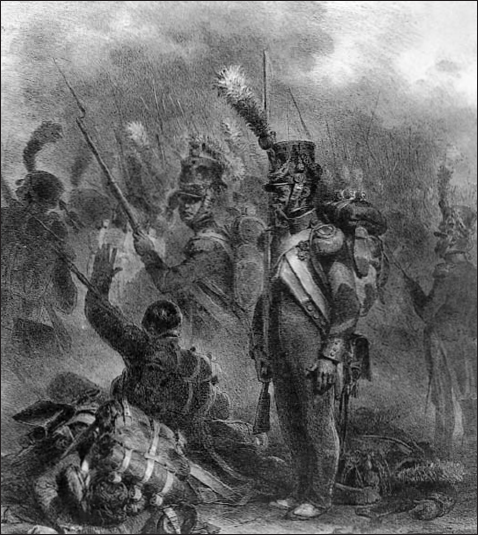

French infantry in the firing line, 1812. A veteran sergeant steadies his men whilst an officer stands coolly behind him.

While Wellington ensured that all his main lines of communication were improved and repaired from the ports of Lisbon and Oporto to the Spanish border, he planned to sever the links between Soult’s army south of the River Tagus and Marmont’s forces north of the river. This involved a daring raid on the bridge of boats and the forts over the Tagus at Almaraz. A force of 10,000 British and Portuguese infantry, commanded by Rowland Hill and supported by a battery of heavy guns, raided Almaraz on 12 May 1812. ‘Daddy’ Hill, as he was known by his men, was probably the only commander trusted enough by Wellington to carry out such as raid, and he did not disappoint his commander-in-chief. In fact, Hill had already demonstrated his ability in an independent command when he attacked and routed a French force at the village of Arroyo dos Molinos in October 1811. The operation against the bridge at Almaraz was carried out with similar elan, his infantry, notably the 50th and 71st Regiments, storming the fort on the southern bank of the Tagus before driving the French defenders back over the bridge of boats. With the French in full retreat, Hill destroyed the bridge and forts and thus severed direct communications between Soult and Marmont.

The hilt of the straight-bladed 1796-pattern Heavy Cavalry sword. A clumsy, often unwieldy weapon, it nevertheless wrought havoc amongst the French infantry when in the hands of Le Marchant’s Heavy Cavalry brigade at Salamanca.

The destruction at Almaraz was a major inconvenience for the French, but Wellington still had to contend with five French armies in Spain. Early in 1812 some 27,000 troops had been removed from the armies of Suchet, Dorsenne, Marmont, Soult and Joseph for service in the army Napoleon was preparing for the invasion of Russia. Other battalions were sent south to replace them, but they were not of the same quality, nor were they as numerous. However, the French armies still numbered some 230,000 men, against which Wellington had just over 60,000. Wellington had several advantages over his French adversaries, the most significant being the co-operation of the Spanish people, a vital factor that was to prove crucial in his campaign in the Peninsula.

The superb 1796-pattern Light Cavalry sabre, as designed by John Gaspard Le Marchant, killed tragically at Salamanca.

Wellington later acknowledged the importance of the Spanish guerrillas in his final victory, and indeed, it is difficult to imagine him achieving it without them. Spain is a vast country, and the French simply could not concentrate enough men to seriously affect Wellington’s position. They may have had an opportunity earlier in the war when Wellington was struggling against both political and military odds to establish himself in the Peninsula, but by 1812, those days were long gone. Wellington had realised early on the vital necessity of cooperating with the Spanish and Portuguese people and by the summer of 1812 he had begun to exert his influence over both the Spanish generals and guerrillas. The stress he placed on having the co-operation of the local people can be gauged by the fact that, when he invaded southern France in the winter of 1813-14, he sent home several thousand Spanish troops who had begun to exact their own revenge on French towns and villages. This may have left him short of men, but he could not risk the sort of resistance movement in France that had played havoc with the French during their occupation of Spain.

The hilt of the 1796-pattern infantry officer’s sword, carried by the majority of Wellington’s officers at Salamanca.

The guerrillas had an equally important part to play in Wellington’s intelligence system. It was, of course, vital to know what was happening ‘on the other side of the hill’, and in this respect the French suffered badly. They undoubtedly had their own network of spies, but the information gleaned from it was trifling when compared to that run by Wellington. In George Scovell, he had an officer who was a master of decoding enemy ciphers, while his own group of ‘correspondents’ kept him regularly informed of French troop movements and numbers. Dr Patrick Curtis, Regius Professor of the Irish College in Salamanca, was probably the best-known of these, and supplied Wellington with a great deal of information prior to the Salamanca campaign. Indeed, Curtis dined with Marmont himself on several occasions, and although suspected by some French officers, was never caught and convicted of spying. The Spanish guerrillas, meanwhile, saw to it that Wellington received as much information as was asked for, while enemy despatches were brought in regularly, often stained with the blood of their former bearers. This was in stark contrast to Marmont’s intelligence system, which relied as much upon the torturing of local people as it did upon the stealth of French officers.

The advantages that Wellington gained through his co-operation with the Spanish guerrillas was therefore of great importance, and despite the numerical superiority of his adversaries he was able to take to the field in the early summer of 1812 full of confidence. Diversionary operations in Andalucia, along the Bay of Biscay and on the eastern coast of Spain were put into operation while Rowland Hill, with some 18,000 regulars, guarded the southern route between the two Iberian countries at Badajoz and Elvas. All was now ready and, on 13 June 1812, Wellington and his army, 48,000 men with 54 guns, crossed the River Agueda to begin their march east. It was the beginning of a momentous eight weeks that took them from the Portuguese border to the Spanish capital, Madrid.