On the morning of 17 June, four days after his advance began, Wellington reached Salamanca. There was little or no resistance and his men began filing into the town the same morning. Marmont, in fact, had withdrawn his army to a position 20 miles north of the town, between Bleines and Fuente Sauco. He had, however, left behind a garrison of 800 men to man three forts in the town, the San Vincente, La Merced and the San Gaetano.

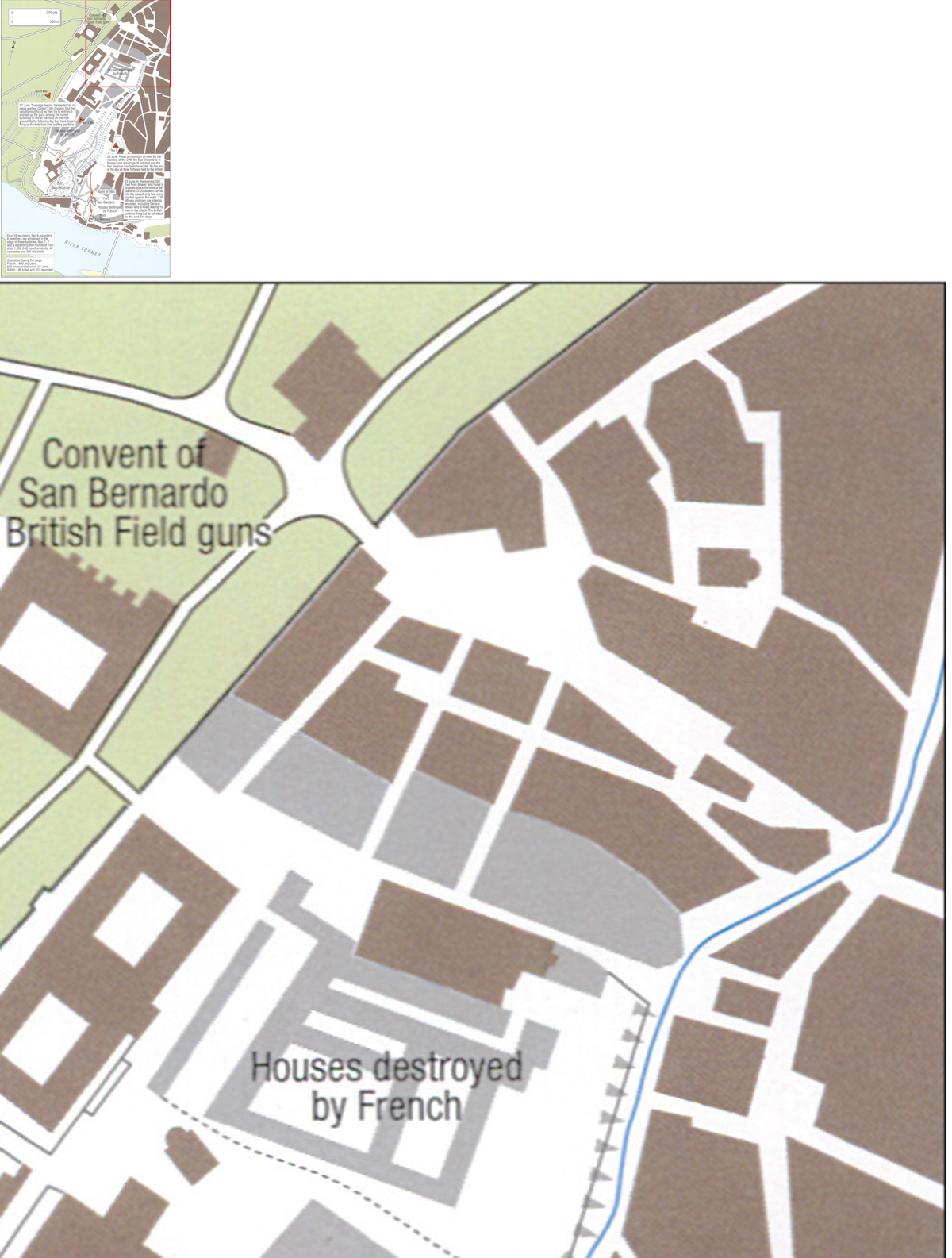

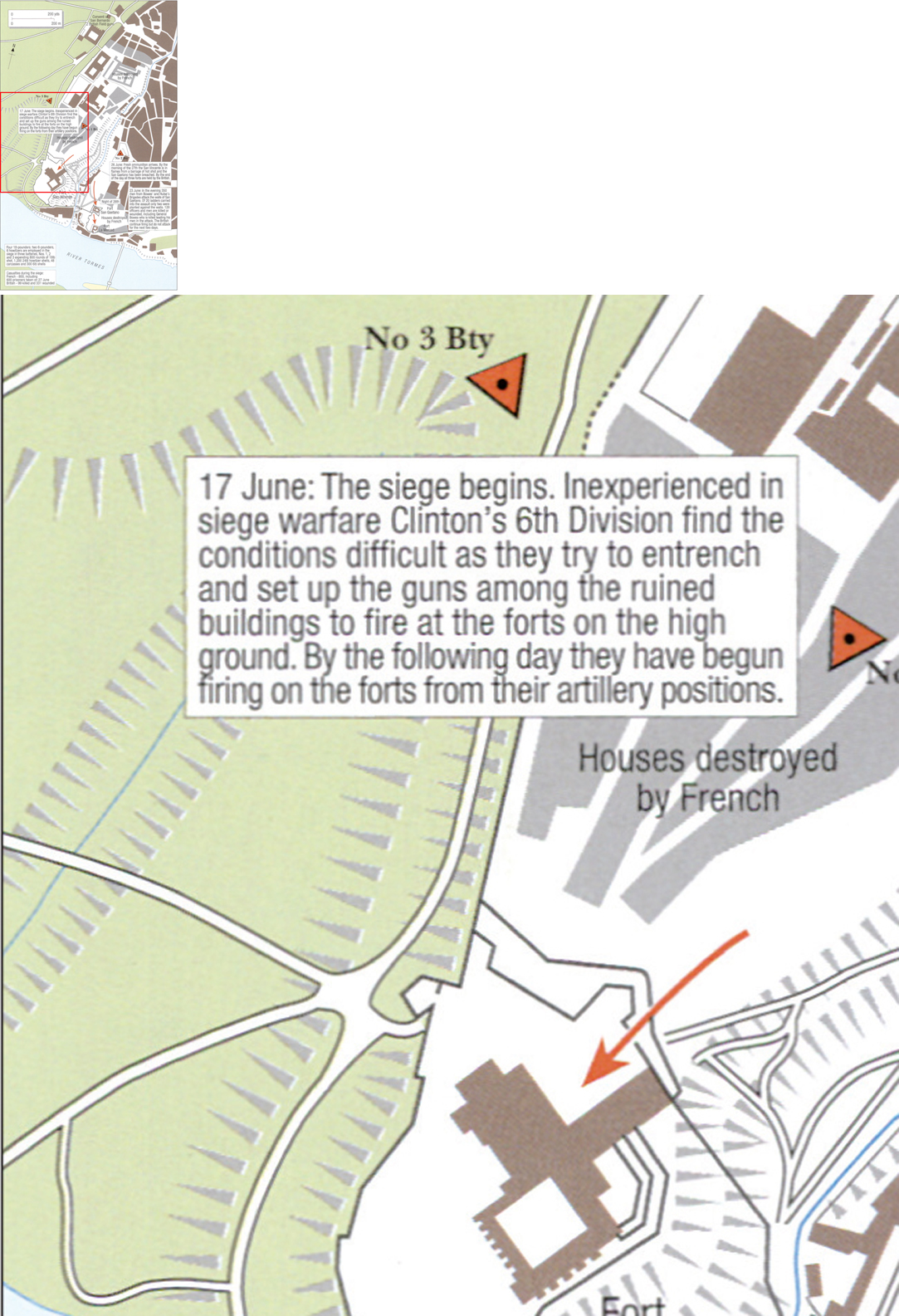

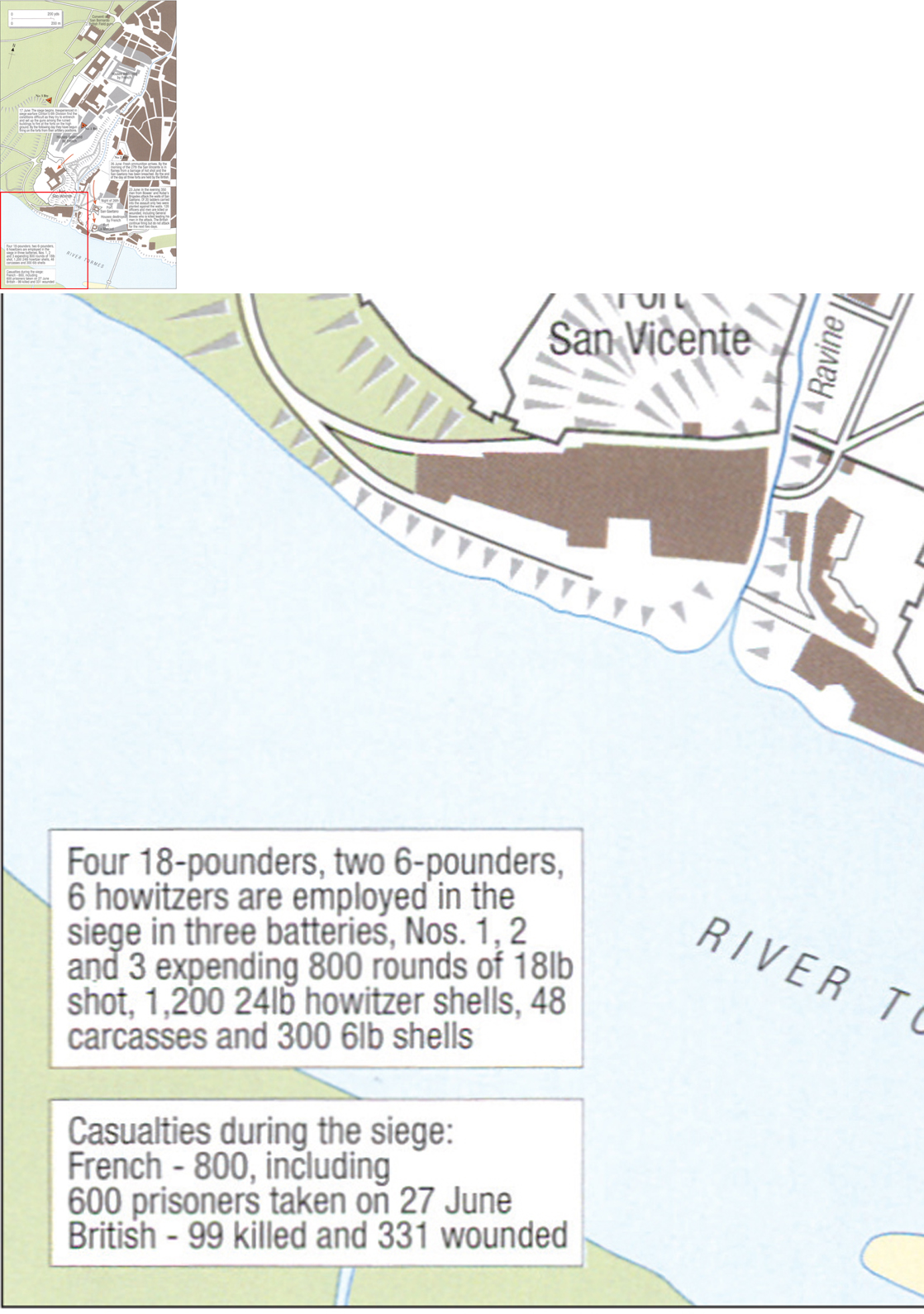

These forts were situated in the south-east of the town, high above the River Tormes. San Vincente was the strongest, boasting some 30 guns. The fort of La Merced mounted only two guns but they dominated the old Roman bridge into the town and were a source of no little annoyance to Wellington’s men. On the basis of reports and sketches provided by his Spanish agents, Wellington believed the forts to be relatively weak and apparently went to Salamanca expecting to face three fortified convents. However, they proved to be much stronger owing to the large amount of stone – hewn from the colleges and buildings that once stood on the same ground – with which the French engineers had been able to strengthen them. The ground upon which the buildings had stood had thus been cleared, and provided a first-class field of fire for the garrison. Moreover, the San Vincente could only be approached across the open ground as it was protected to the south by a cliff, at the bottom of which ran the River Tormes, and to the east by a deep ravine. Matters were not helped either by the usual lack of a decent Allied siege train, something that would plague them at Burgos three months later. Indeed, there were only four 18-pdrs. available to Clinton for the reduction of the forts, although six other heavy guns were on their way to Salamanca. And so, while Wellington and the bulk of his army took themselves off to a position at San Cristobal, three miles north of Salamanca, Clinton and his 6th Division stayed behind in the town to lay siege to the three forts.

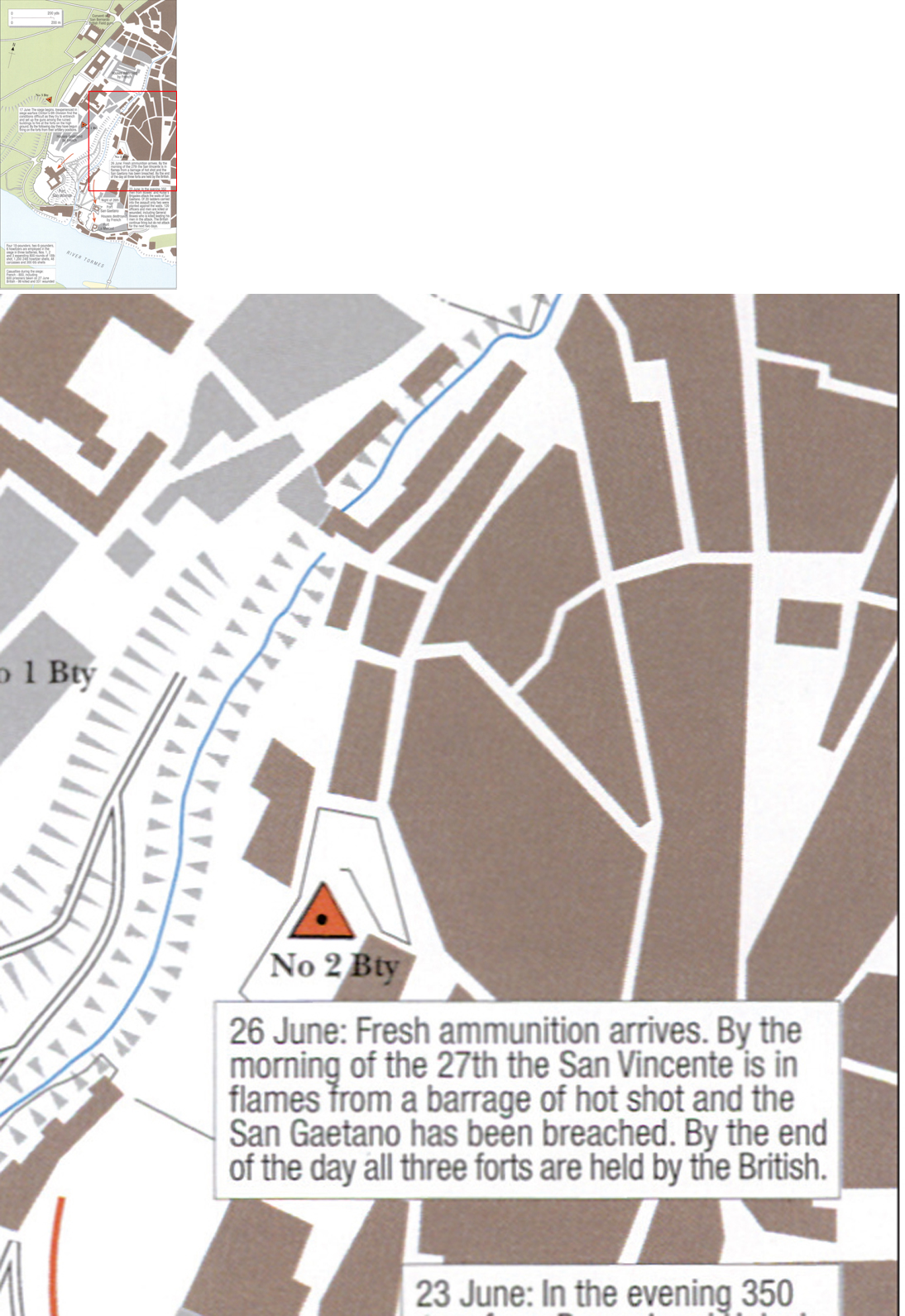

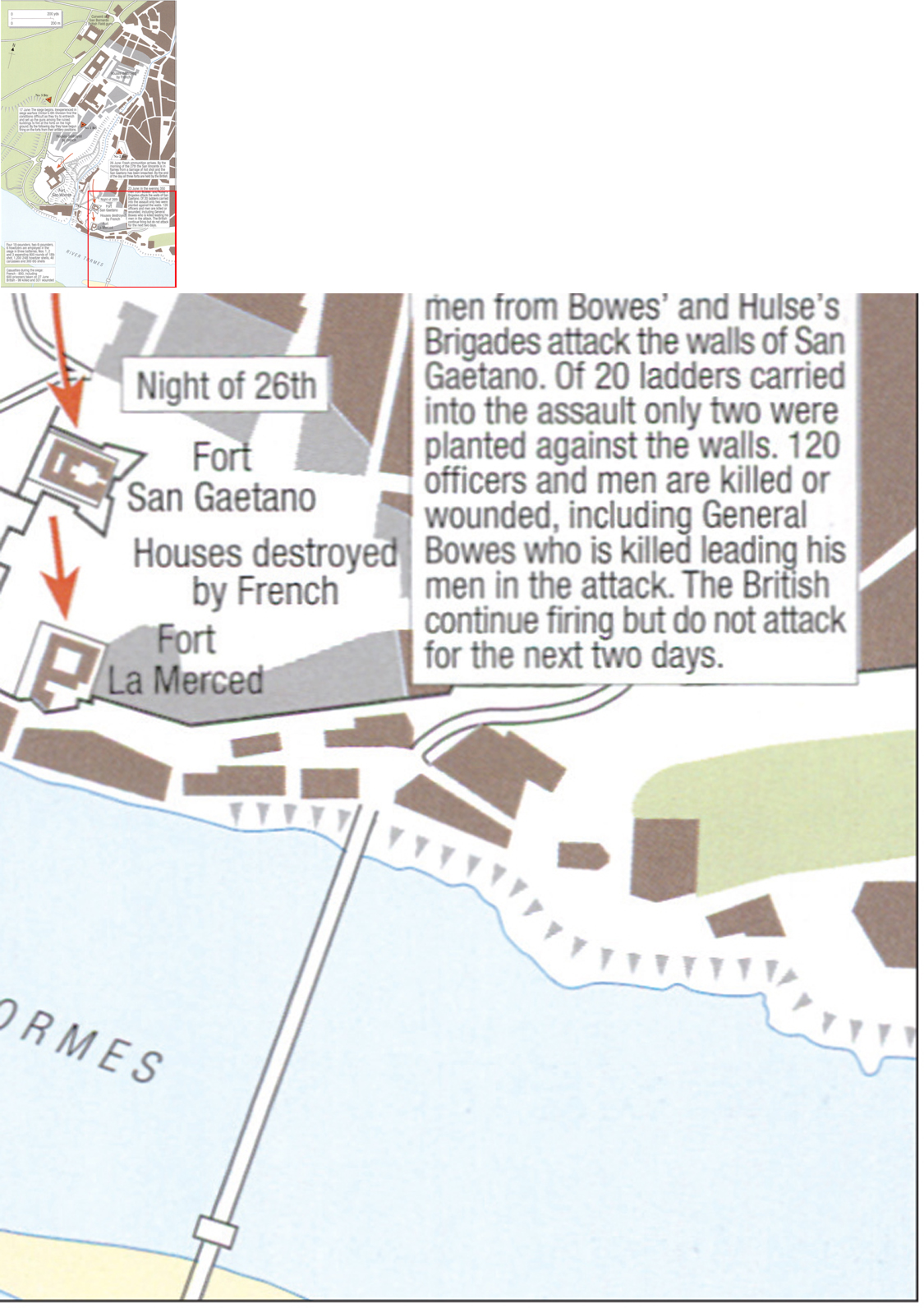

The siege of the Salamanca forts began on the night of 17 June, but it was to be a full ten days before the garrisons finally capitulated. Clinton’s 6th Division had little experience of siege warfare, although even Wellington’s veterans, the 3rd, 4th, 5th and Light Divisions, would probably have struggled to deal with the situation. The rubble and debris scattered round, combined with the old, very solid foundations of the buildings previously on the site, made entrenching very difficult, although the Allied riflemen made good use of the debris as cover from which to snipe at the French defenders. The unsatisfactory siege dragged on until the evening of 23 June, when 350 men from Hulse’s and Bowes’ brigades of the 6th Division were thrown against the walls of the San Gaetano fort in a futile attempt to escalade it. Of the 20 ladders carried into the assault, only two were actually planted against the walls at a cost of some 120 officers and men who were either killed or wounded. Among the dead was Gen. Bowes who had insisted on joining his men in the attack. Bowes was wounded early on, but after being patched up, returned to lead his men and was fatally wounded.

The view from Wellington’s position on 20-22 June at San Cristobal, three miles north of Salamanca. Marmont’s numerically inferior army deployed on the plain in the distance, causing Wellington to remark, ‘It’s damned tempting. I’ve a good mind to attack ’em.’

Despite the setback, fresh supplies of ammunition arrived on 26 June. By the morning of 27 June the San Vincente was in flames from a barrage of hot shot, while a practicable breach had been made in the San Gaetano; at the end of the day all three forts were in Allied hands. Some 600 unwounded Frenchmen thus marched out of the forts and into captivity while Wellington was left to reflect upon the 430-strong casualty list which had been the cost of this frustrating ten-day episode.

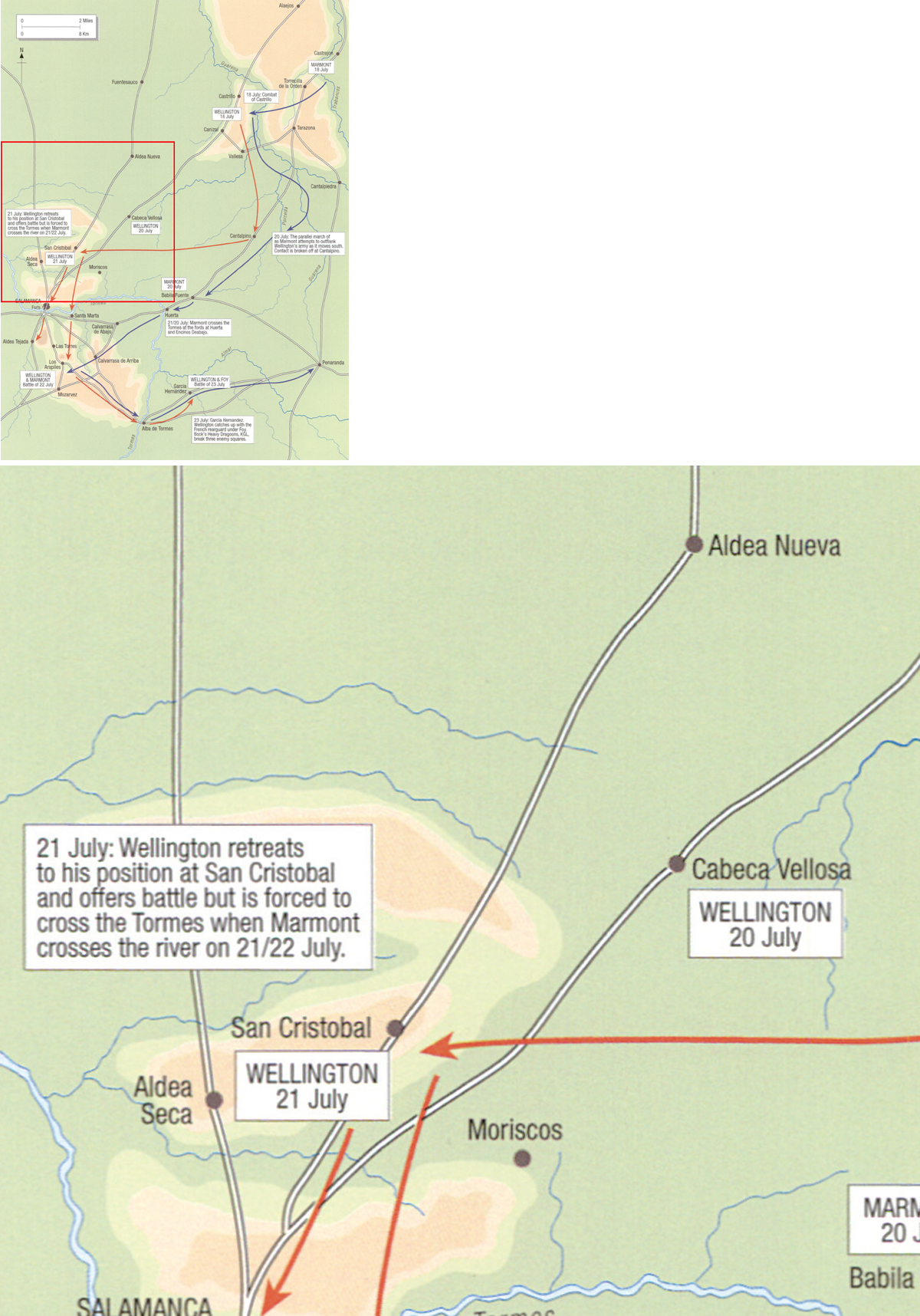

While the siege of the Salamanca forts was in progress there had been much marching and counter-marching by both armies during a period which has become one of the memorable features of the Salamanca campaign. Having left Clinton’s 6th Division in Salamanca, Wellington’s main army had marched north to the heights above San Cristobal, three miles outside the town, on 19 June. This position was a strong one, giving Wellington a long, sloping, commanding height with a concealed reverse slope – his trademark position and stretched from the village of San Cristobal itself as far as the River Tormes at Cabrerizos, on which rested his right flank.

The following day Marmont arrived in front of San Cristobal, intent on relieving the forts in Salamanca. From his position upon the heights above the village Wellington gazed out over the vast plain before him as Marmont’s force, some 25,000 men, manoeuvred. In fact, Marmont had with him all of his force, save for Bonnet’s division which was still in the Asturias. The French advanced and soon were just 800 yards from the Allied position, prompting an outbreak of cannon-fire from British guns as if to warn off their adversaries. The French reply was as much in defiance as it was an attempt to serve as a signal to the beleaguered garrisons of the Salamanca forts. There was little direct action on 20 June, although French troops did attack the village of Moriscos, situated under the Allied right centre, which was held by the 68th Light Infantry. Despite a sharp attack on the village the 68th held firm until nightfall when Wellington ordered them to fall back, having suffered 50 casualties.

Wellington welcomed the French attack and hoped that Marmont would follow it up the next day. Indeed, at dusk he stood in full view of the French gunners, issuing orders to his generals and giving them detailed instructions as to their role on the following day. This impromptu meeting was cut short, however, when a few shots came bouncing in among them, prompting a prudent withdrawal. A serious attack by the French against a numerically superior force – Wellington outnumbered Marmont by 8,000 men – occupying a strong position would have been dangerous to say the least. Moreover, in the event of failure, which would almost certainly have been the outcome, the plain behind Marmont offered little in the way of protection. Certainly, there was no feature similar to the wood that was to save him from total destruction a month later at Salamanca.

Unfortunately for Wellington, Marmont did nothing on 21 June other than ride forward to reconnoitre Wellington’s position. There was some skirmishing on the Allied right flank, but the day was one of inactivity with both sides remaining within cannon-shot of each other without doing any harm. Wellington was up well before dawn on 22 June and soon realised that Marmont was not about to attack him. He decided to draw him into a battle instead and, at 7am, Wellington ordered the 51st and 68th, along with the skirmishers from the Light Brigade of the King’s German Legion, to attack the French piquets upon a knoll above the village of Moriscos. In the event of a strong French counterattack, Sir Thomas Graham was to support these troops with the whole of the 1st and Light Divisions. The small Allied force suffered 50 casualties in driving the French from the knoll, but there was no French retaliation. The French piquets simply retired 200 yards down to Moriscos itself. That night, Marmont withdrew his army to Aldea Rubia, some six miles to the east.

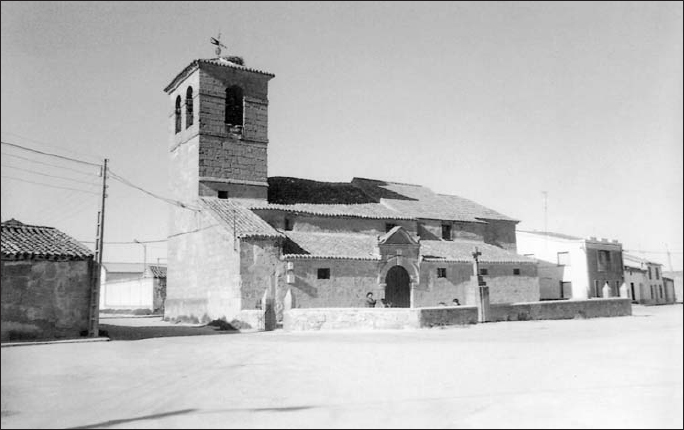

The church at Moriscos. The 68th Light Infantry were withdrawn from here by Wellington after some sharp fighting on 20 June.

THE STORM ON THE EVE OF SALAMANCA

On the night of 21 July 1812 a tremendous storm blew up with crashes of lightning, thunder and torrential rain. The camp of the 5th Dragoon Guards was a scene of pandemonium and chaos as frightened horses bolted or rode over their riders sleeping on the ground. The regiment suffered 18 men hurt, while 31 horses bolted into the night. The occurrence of a storm before a battle was to become an omen of victory for Wellington’s men. Indeed, similar storms occurred on the nights preceding Sorauren and, of course, Waterloo.

The situation on 20-22 June was an intriguing one, with both armies passing up the opportunity to attack each other. On 21 June Wellington’s force at San Cristobal numbered some 37,000 Anglo-Portuguese infantry, as well as 3,500 cavalry. He could also call upon the 3,000-strong Spanish division of Carlos de España. Marmont, on the other hand, could muster just 28,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Moreover, Wellington possessed a fine position overlooking his French adversary, who himself maintained a dangerous position with little defensive cover. In such a vulnerable position Marmont could not have got away without putting up a fight and the odds were firmly in favour of a crushing Allied victory; the Allied cavalry, in spite of its patchy reputation, would surely have had a field day. As he watched and waited for Marmont to attack, Wellington himself is reputed to have said, ‘Damned tempting! I have a great mind to attack ’em’. He did not, however, something he may have regretted during the afternoon when the divisions of both Thomières and Foy, numbering just over 9,500 men, arrived to join Marmont’s army.

Castrejon, the scene of the skirmish on 18 July during which Wellington and Beresford both had to draw their swords to fend off hovering French cavalry which had charged over the hills to the right of this photo.

Ironically, while Wellington waited for Marmont to attack, the French marshal was holding a ‘council-of-war’ with his generals, two of whom, Maucune and Ferey, actually advocated an attack. However, both Clausel and Foy urged Marmont to be more cautious. Foy himself had good reason to remember Vimeiro and Busaco, and did not wish to receive similar treatment. And so Marmont was allowed to march away from what was undoubtedly an extremely dangerous situation. The remarkable thing is that Marmont did not realise this, and appears never to have considered for a moment that Wellington was capable of such an offensive movement. In fact, in his despatch to King Joseph he simply said that he would not attack while his numbers were not at least equal to the Allies and that he withdrew in order to await the arrival of 8,000 reinforcements from Gen. Caffarelli and the Army of the North.

During the next four days Marmont’s army manoeuvred to the east of Salamanca with a view to relieving the Salamanca forts. At one stage Marmont even sent some 12,000 men across the Tormes via the fords at Huerta in an attempt to force Wellington into dividing his force. This move was thwarted by a similar move across the Tormes, closer to Salamanca, by Graham with the 1st and 7th Divisions.

At dawn on 27 June the governor of the San Vincente fort signalled that he was capable of prolonging the defence for a further three days. This message increased Marmont’s determination to relieve the forts and accordingly he planned a move south. His 40,000-strong army would cross the Tormes at Alba de Tormes from where it would march northwest to Salamanca. Such a move was extremely risky because Wellington, already outnumbering Marmont by nearly 4,000 men, would have the use of Clinton’s 6th Division which would have been freed from the siege of the forts, something Marmont would not have known until too late had he executed the move. Ironically, such a march would have brought him to the very same ground as that upon which he was destined to be defeated on 22 July. Before he got underway, however, Marmont received news that the Salamanca forts had surrendered, the march across the Tormes was abandoned and a potentially calamitous move was averted, albeit for a matter of weeks.

The fall of the Salamanca forts was the second of two blows for Marmont in the space of two days. The previous day he had received news from Caffarelli that due to a threat to Bilbao from Sir Home Popham, who was co-operating with Spanish regulars and guerrillas, he would not now be marching to his assistance and would instead march north to avert this new threat. This, along with the fall of the Salamanca forts on 27 June, settled the business as far as Marmont was concerned. He had manoeuvred around Salamanca for the past week or so, often in dangerous situations, in order to attempt the relief of the forts. But now the forts had surrendered and with little immediate prospect of reinforcements, there was little benefit to be gained from remaining any longer.

Therefore, at dawn on 28 June Marmont’s army began its withdrawal north-east towards Valladolid and a new defensive position behind the Douro River. Marmont realised such a move would isolate him from Madrid, but it would, on the other hand, take him closer to Bonnet, whose 8th Division was expected from the Asturias. Once Bonnet had joined him Marmont would be able to field an army equal, at least in number, to Wellington’s.

There was little movement by either army during the first two weeks of July. The French concentrated behind the Douro between Toro and Tordesillas, while Wellington’s massed south of the Douro between La Seca and Rueda. During this period of inactivity the men of both armies bathed regularly in the Douro close to Pollo and it was not uncommon to see both French and British troops in the water at the same time.

On 7 July Marmont was finally joined by Bonnet’s division, although unknown to him Caffarelli, Suchet and Soult had each sent despatches to Joseph informing him that they could not spare any men for the Army of Portugal. Joseph was aware of the danger in which this might place him should Marmont be defeated by Wellington. Having weighed up the situation, Joseph recalled all garrisons from Castile in order to reinforce Marmont. However, this valuable 13,000-strong reinforcement, under Joseph himself, did not leave Madrid until 21 July, and did not arrive in time to have any bearing on the outcome of the battle of Salamanca.

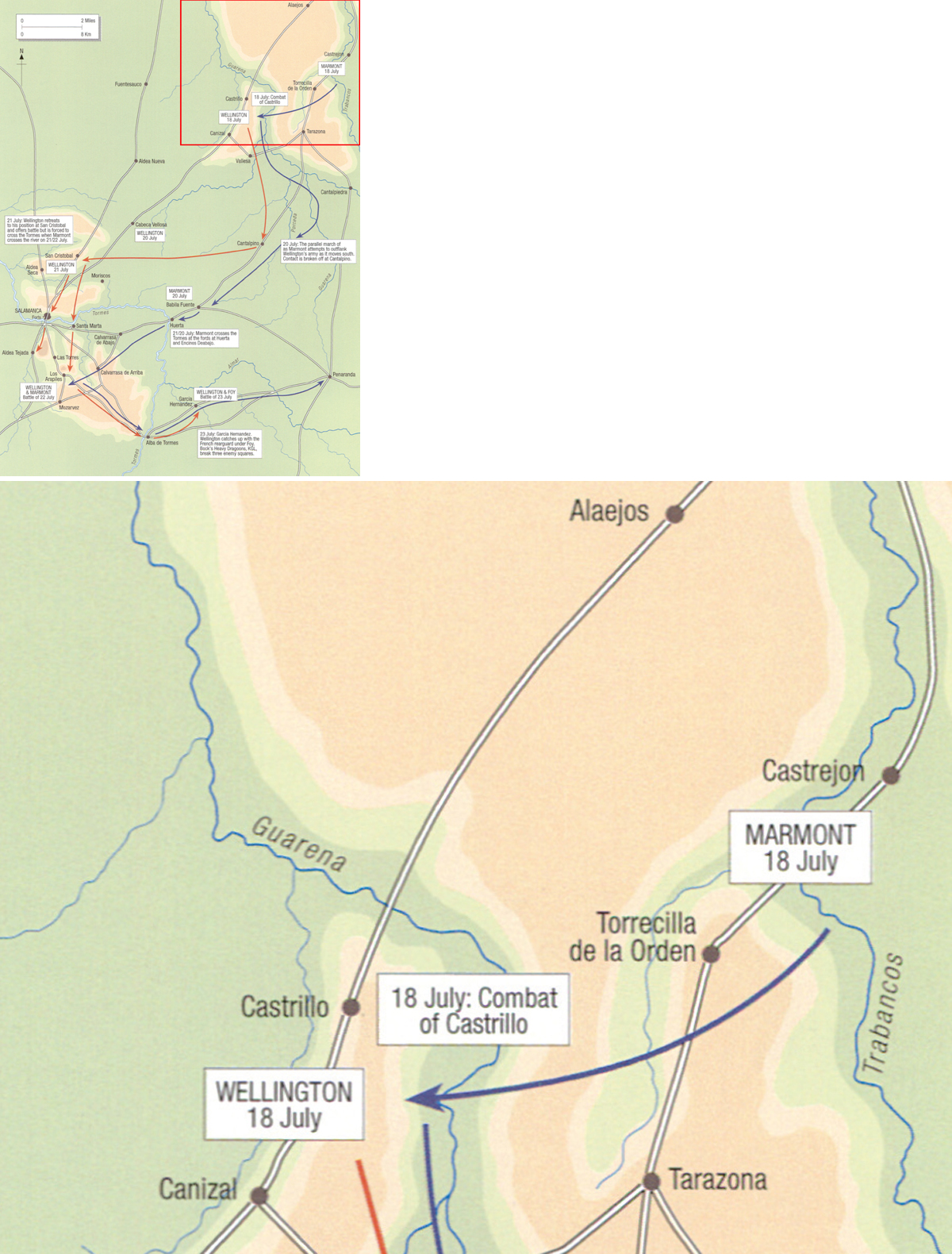

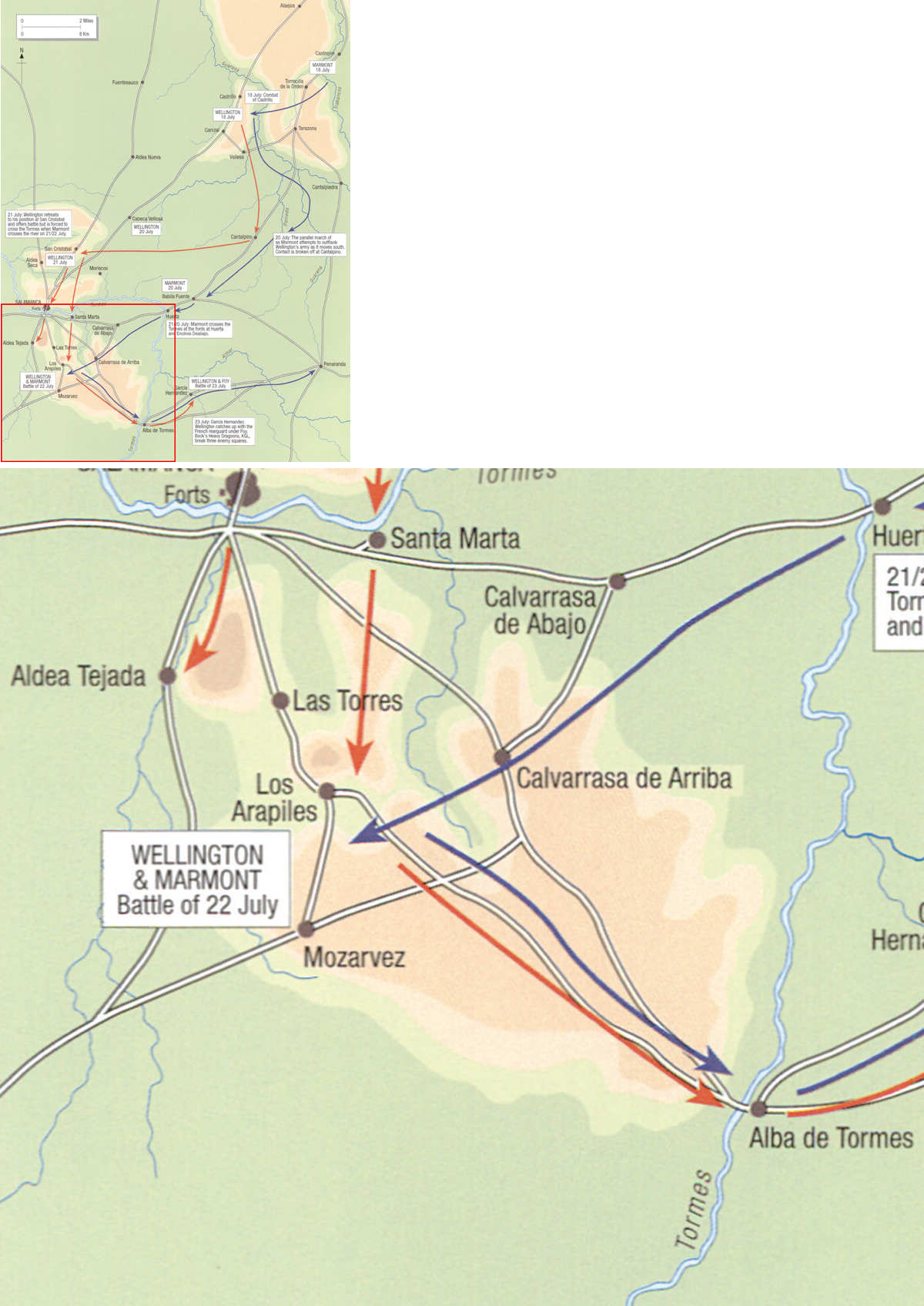

The final stage of the preliminaries leading to the battle began on 16 July with a move by Marmont across the Douro. He pushed Bonnet’s and Foy’s divisions across the river at Toro, while the bulk of his army concentrated at Tordesillas. Then, after Wellington had shifted part of his force to Fuente la Pena and Canizal in anticipation of a French advance south from Toro, the two French divisions swiftly recrossed the Douro, broke down the bridge at Toro and rejoined Marmont’s main army which then crossed the Douro at Tordesillas during the night of 16 July. This move was calculated to wrong-foot Wellington, which in fact it did. Early on the morning of 17 July Marmont’s troops poured over the Douro at Tordesillas, passing through the area recently occupied by Wellington’s troops who had marched south-west. Fortunately, the Allied commander-in-chief was not totally fooled and, ever suspicious and cautious, he had halted the 4th and Light Divisions, as well as Anson’s brigade of cavalry, at Castrejon. The rest of his army, meanwhile, was positioned between Castrillo and Canizal. Once aware of Marmont’s real intentions, Wellington decided to pull his rearguard back to rejoin the main body of the army.

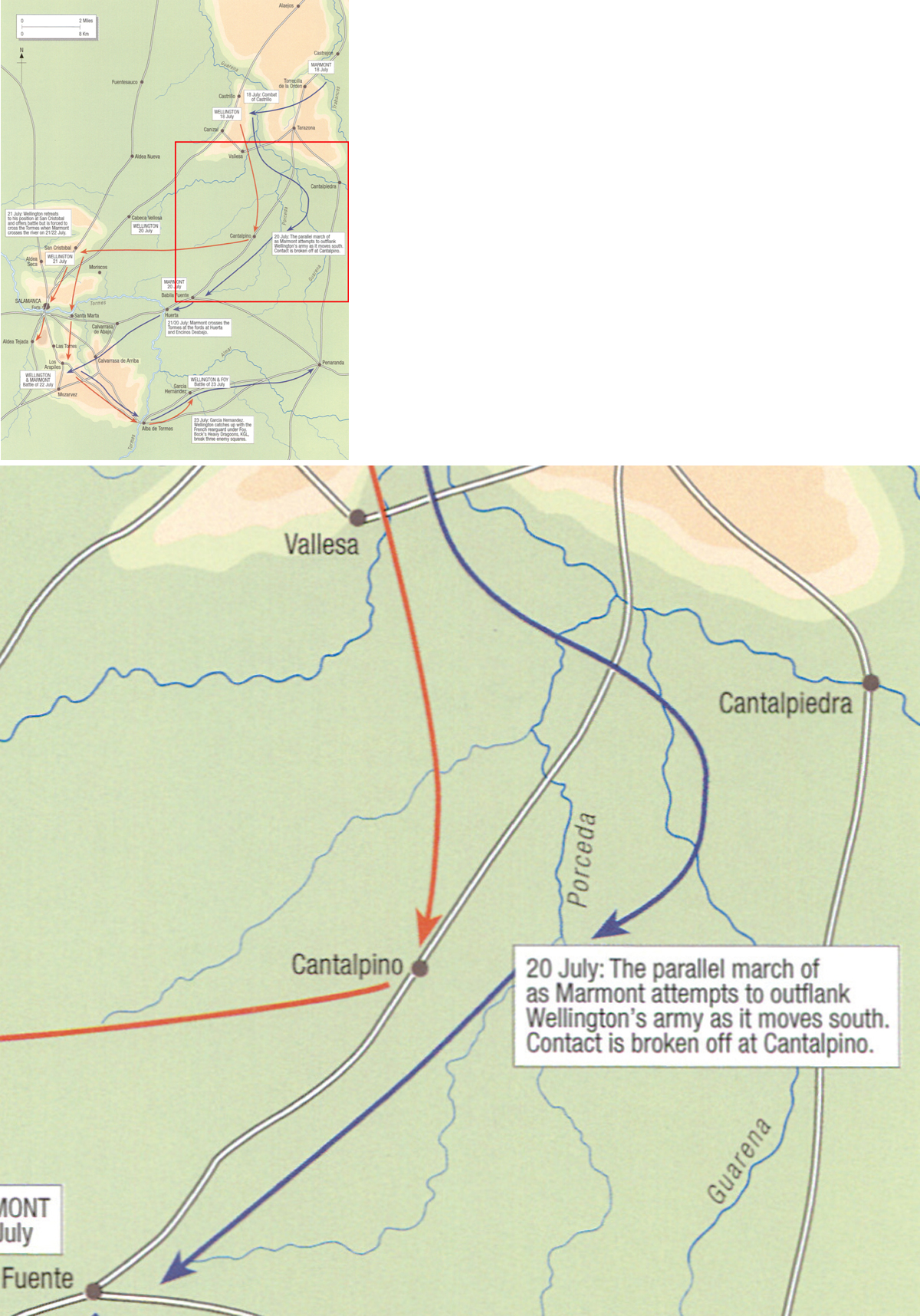

THE PARALLEL MARCH

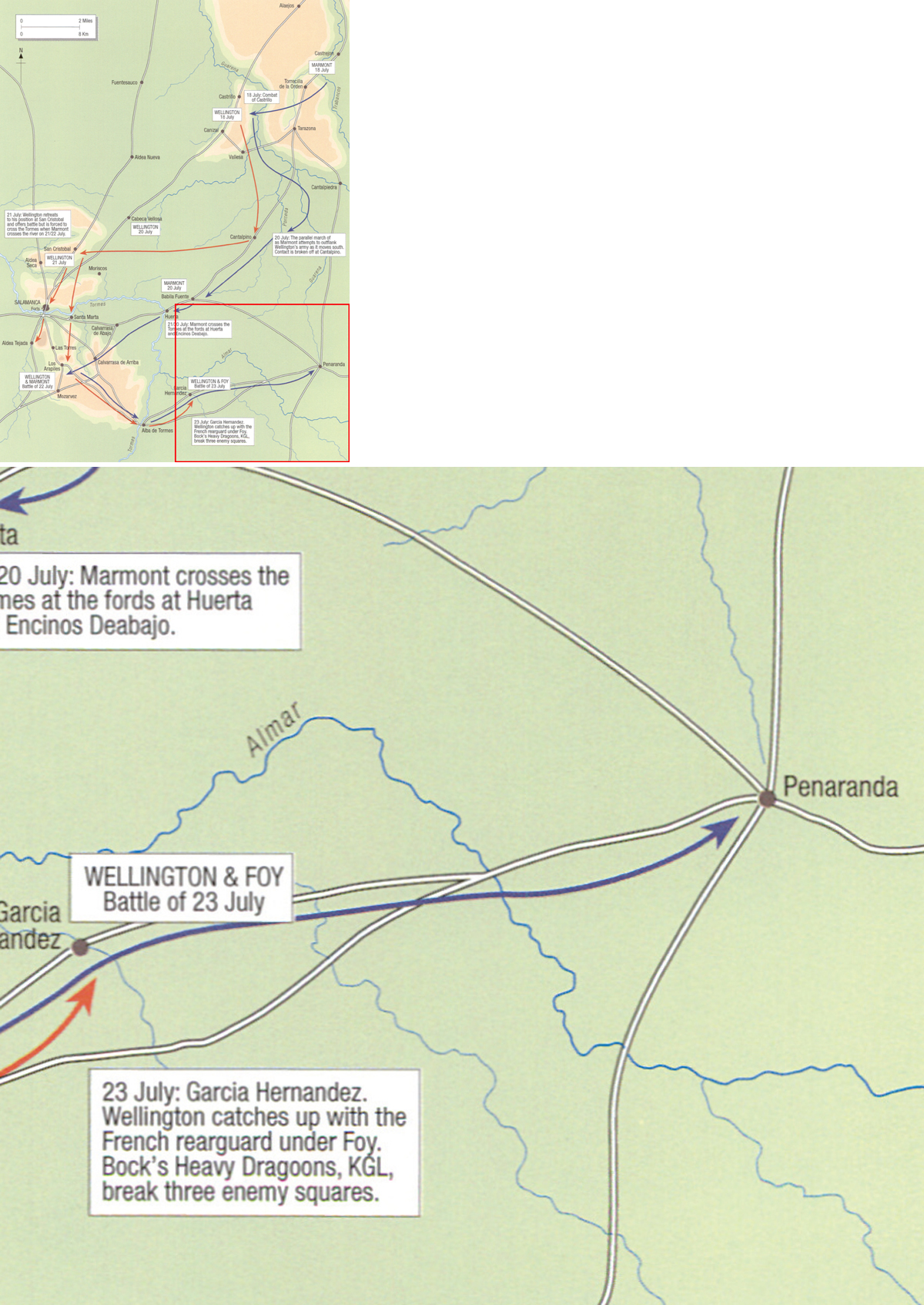

Throughout the long, hot day of 20 July 1812, both armies marched parallel to each other, separated by just a few hundred yards. The situation occurred when Marmont attempted to get around Wellington’s left flank as he marched south but each time the French moved further to the east, Wellington did likewise, his men keeping a wary eye on their adversaries over their left shoulders. The two armies parted company at Cantalpino when Wellington moved west towards San Cristobal, Marmont continuing on to the fords over the Tormes at Huerta. Although it appears that Marmont was threatening Wellington’s right, it must be remembered that the Allied army was marching south and therefore it was Wellington’s left that was threatened.

Never one to delegate too often, Wellington rode forward himself to initiate the move at daylight on 18 July. As he arrived at Castrejon he found Allied cavalry patrols, under Cotton, already engaged with French cavalry who were advancing in strength. There followed a sharp skirmish between Allied cavalry and artillery and French cavalry, supported by a strong column of infantry. Wellington rode forward with Marshal Beresford and their staffs at the precise moment when a squadron of French cavalry charged upon the flank of the Allied guns, sweeping aside a squadron of 12th Light Dragoons behind them. The 12th were thrown back upon their own supporting troops, a squadron of the 11th Light Dragoons. Apparently, in the confusion, a staff officer shouted the wrong order and the 11th turned about, sweeping down on Wellington, Beresford and their staffs, forcing them to draw their swords as the French got in among them. It was a close call, and there was a very real chance that Wellington might have been either killed or captured. In the event, the 11th Light Dragoons, realising the mistake, turned and inflicted heavy losses on the French who were driven off.

Marmont’s thrust south initiated a period of complex manoeuvres during which the French marshal attempted to get round Wellington’s left flank. However, each French move to the south-east was countered by a similar move by Wellington. On 19 July, in fact, both armies stood motionless in front of each other, separated only by the Guarena River, just to the north of the villages of El Olmo and Vallesa. While Marmont reconnoitred Wellington’s position, both sides took the opportunity for some well-earned rest. The men had suffered an exhausting march beneath the searing July sun and any short slop was welcome. As the afternoon wore on neither side moved until, at around 4pm, Marmont’s columns lurched back into life and continued marching south-east on the right bank of the Guarena. Wellington duly marched in the same direction, on the left bank of the river.

It was across this barren-looking plain that the famous ‘parallel march’ of both Wellington’s and Marmont’s armies took place on 20 July. The armies went from right to left of this picture. This photograph was taken from the heights north of Cantalpino.

Both armies continued to march on opposite sides of the Guarena River the next day, until Wellington’s army reached the Poreda, a tributary of the Guarena. His men continued marching south-east, on the left bank of the Poreda, with Marmont’s men keeping to the right bank of the Guarena. This left a triangular area between the two rivers upon which neither army ventured, other than a few cavalrymen. This was the famous parallel march of 20 July, with Wellington’s army in three parallel columns, Marmont’s in two, each army watching and waiting for any signs of disorder among the other. The two armies got even closer when Marmont ordered his men to cross to the left bank of the Guarena to march south-west in the direction of Cantalpino. It was one of the most memorable days of the Peninsular War, as the two great armies marched at speed, with parade ground precision, within a few hundred yards of each other. Thousands of tramping feet, and hundreds of wheels of the guns and wagons, kicked up huge clouds of dust which added to the stifling heat, and made for an uncomfortable if unforgettable march. Indeed, Marmont himself later said that he had never seen such a magnificent spectacle as the parallel march of two armies of over 40,000 men each at such close quarters.

By midday the two armies neared the village of Cantalpino and unless either of them changed direction they would collide with each other there. Marmont’s route just to the north of Cantalpino took him across some higher ground than the Allies and just as Wellington’s leading brigades passed through it, the French marshal ordered some of his guns to open fire. Wellington, however, gave orders to his commanders not to return fire, but instead his divisions veered south-west, away from the village, and in doing so refused to give battle.

By late afternoon the two armies had lost sight of each other and Wellington ended the day with his troops occupying the heights of Cabeza Vellosa and Aldea Rubia, a good defensible site. Marmont, meanwhile, occupied a position with his left flank resting upon the fords across the Tormes at Huerta.

The final run up to the battle of Salamanca got underway at dawn on 21 July when Marmont’s troops forded the Tormes at Huerta and began filing south. This move left Wellington with little option but to abandon Salamanca, for if he did not he risked having his communications with Ciudad Rodrigo cut. Therefore, on the afternoon of 21 July, the Allied army began to plunge into the Tormes at the fords of Cabrerizos and Santa Marta. This move lasted well into the afternoon, but by nightfall both armies occupied positions running north–south, the right of Marmont’s army resting upon Machachon with the left upon Calvarrasa de Arriba. Wellington’s army had its left flank upon the Tormes at Santa Marta and its right upon the high ground to the north of the Lesser Arapil hill. The only troops still on the northern bank of the Tormes were D’Urban’s Portuguese cavalry and the 3rd Division, under Edward Pakenham.

The night before the battle of Salamanca was marked by a tremendous storm when bolts of lightning caused chaos among the cavalry of both sides. Scores of troopers were injured by their horses who trampled on them in their panic. The rain fell in torrents, and all those present agreed that a more violent storm had seldom been witnessed. For Wellington’s men, however, such a storm would soon be seen as an omen of victory, one that would be repeated before Sorauren and, of course, on the eve of Waterloo.