The British Army in the Peninsula was commanded by Sir Arthur Wellesley who, following his victory at Talavera in July 1809, had been created Marquis of Wellington. Wellington commanded the army in the Peninsula from the very outset of the campaign in the summer of 1808, until the end of the war in April 1814, without a single spell of home leave, save for a short spell when he was recalled to Britain following the Convention of Cintra. Born in 1769, Wellington had served in Flanders in 1794-95 and, more notably, in India between 1797 and 1804 where he achieved some fine victories, such as Assaye in 1803, which he later described as one of his greatest successes. In 1808 he had been given command of a force destined to embark upon a campaign in Venezuela, following on from Beresford’s and Whitelocke’s forays in South America in 1806 and 1807. However, at the outbreak of the Peninsular War the force was ordered to Portugal instead. Many of Wellington’s problems throughout the early stages of the war until 1812 have been dealt with in the previous chapters. He was greatly assisted by his brother Richard Wellesley, who was British ambassador in Madrid and who proved to be a great help in getting the otherwise dilatory Spaniards to move in support of their British allies.

Sir Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, 1769-1852. After a painting by Heaphy, depicting him at the siege of San Sebastian. Wellington commanded the Anglo-Portuguese army in the Peninsula between 1808 and 1814 and, save for a period of six months following the Convention of Cintra in August 1808, did so without a single day’s leave.

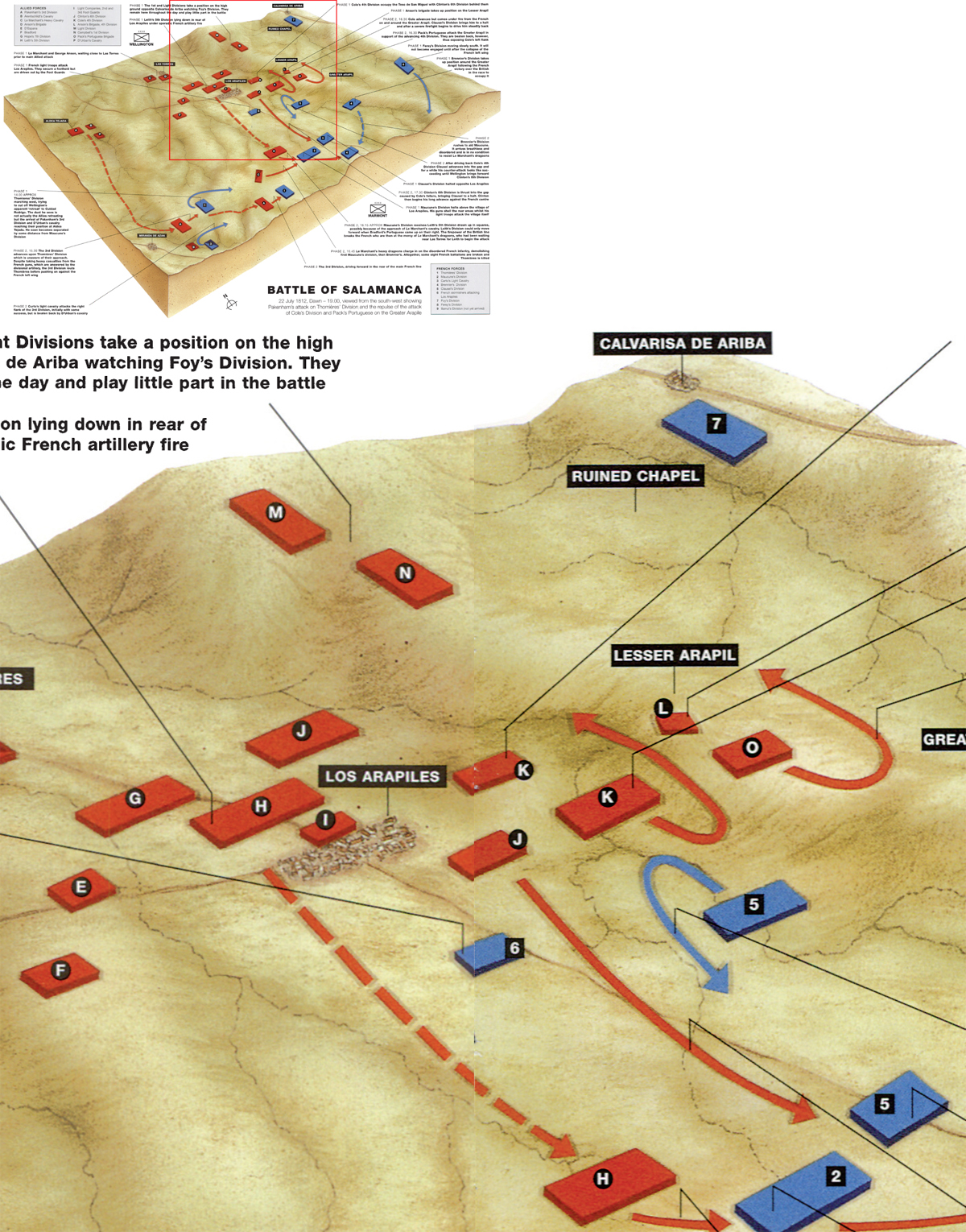

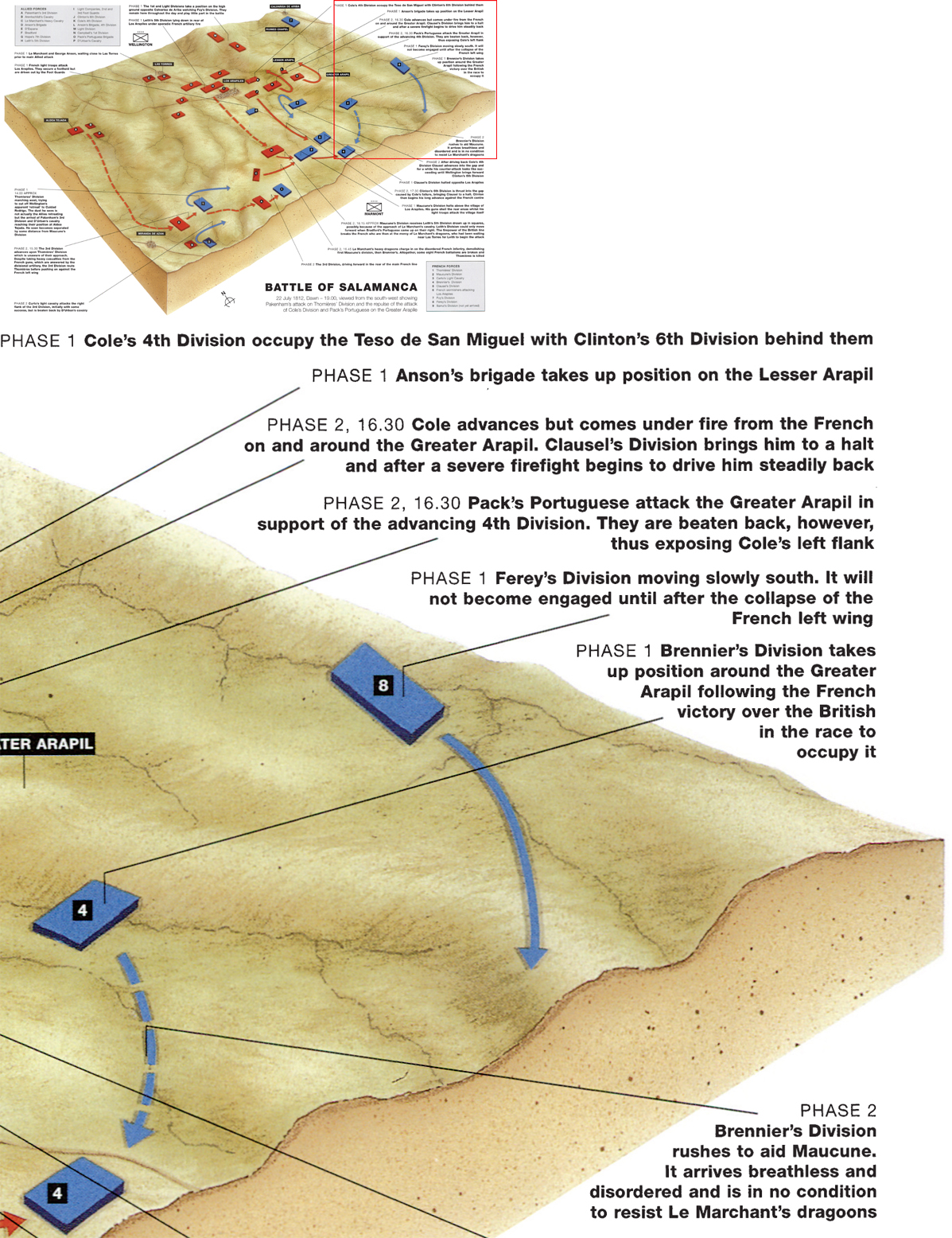

General Clausel, 1769-1830. Clausel commanded the French army at Salamanca after both Marmont and Bonnet had been incapacitated. His counter-attack after Cole’s failure almost won for the French a drawn battle at Salamanca, if not victory itself.

General Maximilien Foy, 1775-1825. Foy commanded the 1st Division of the Army of Portugal at Salamanca, he later wrote his own account of the war in Spain as well as his own memoirs.

Sir Galbraith Lowry Cole, 1772-1842. Cole commanded Wellington’s 4th Division at Salamanca and was wounded during the battle. He later married on the eve of Waterloo and so missed the great battle there in 1815.

Sir Dennis Pack, 1772-1823. Pack had been taken prisoner twice during the ill-fated South American campaigns of 1806 and 1807. He served with distinction in the Peninsula and at Waterloo. He commanded a Portuguese brigade at Salamanca.

William Carr Beresford, 1764-1854. Beresford was one of Wellington’s most trusted subordinates who nevertheless blotted his copybook by his handling of the army at Albuera on 16 May 1811. He is chiefly remembered for his reorganisation of the Portuguese army in the Peninsula.

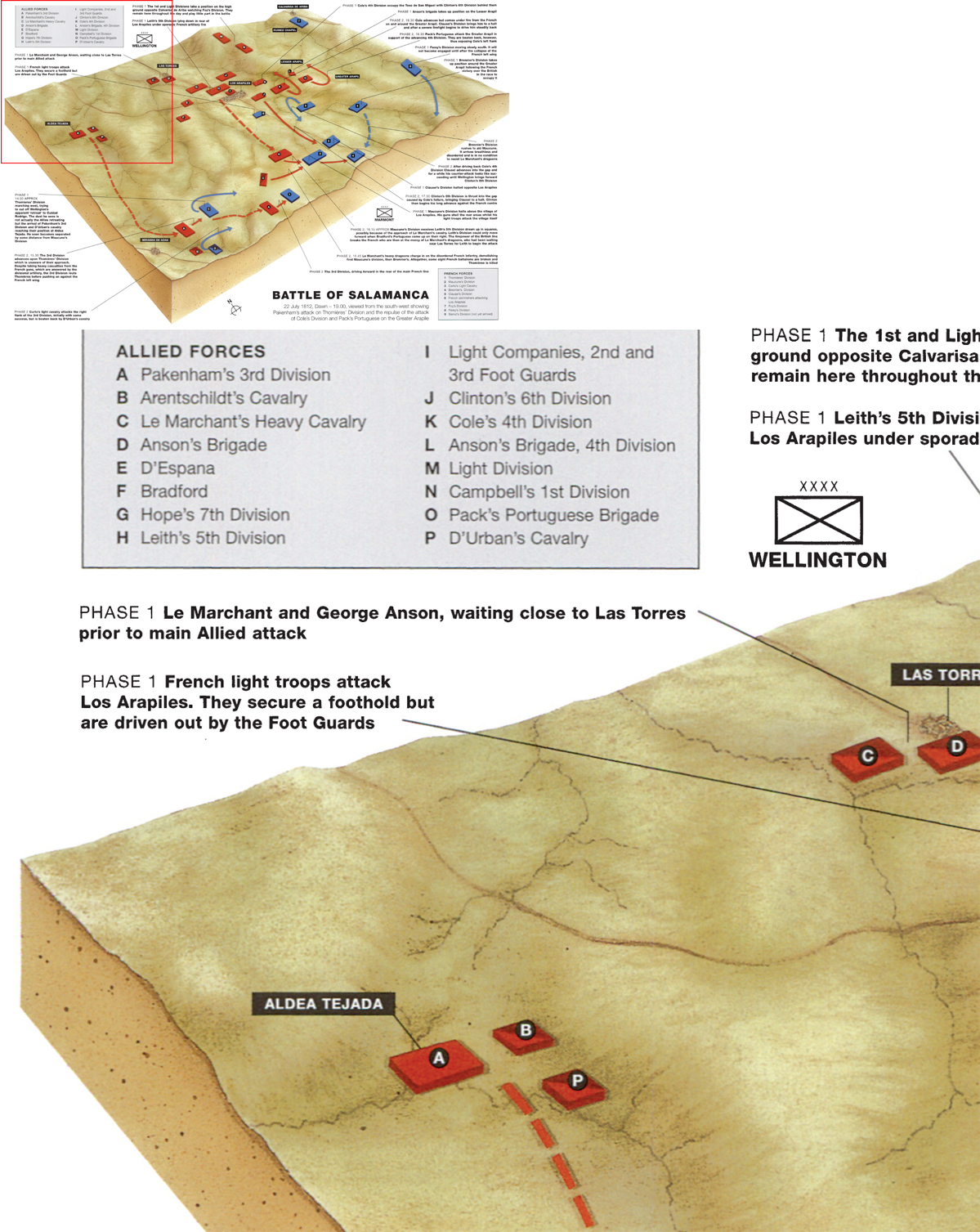

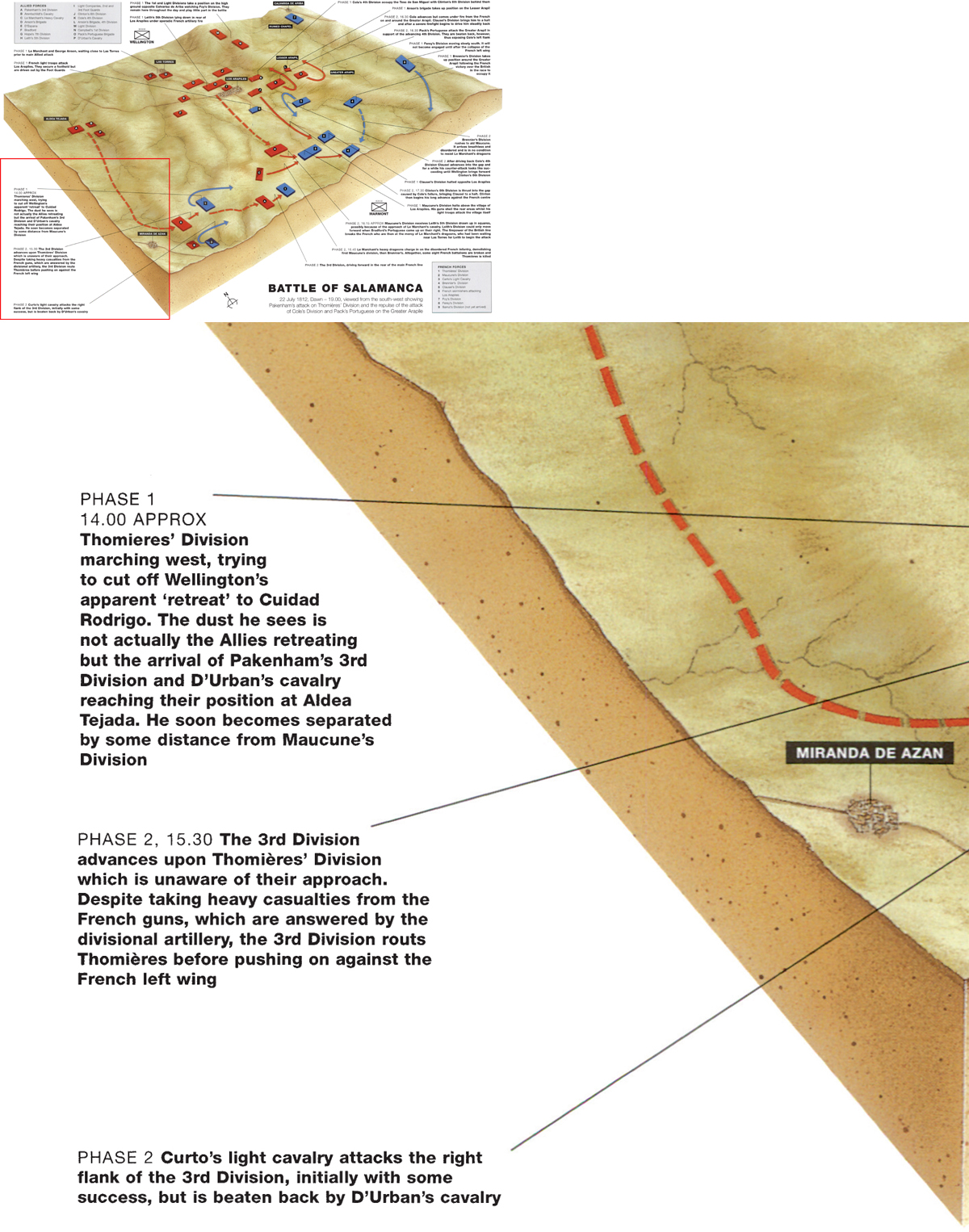

Wellington had lost the commander of his Light Division, Robert Craufurd, during the assault of Ciudad Rodrigo, as well as a host of fine regimental officers at the bloody storming of Badajoz in April 1812. In spite of these losses, however, he possessed many fine divisional and regimental officers, who would go on to distinguish themselves at Salamanca. His brother-in-law, Edward Pakenham, was to become one such hero. Born in 1778, Pakenham had been with the Peninsular army since 1810 and commanded the ‘Fighting’ 3rd Division of the army in the absence of the fiery Welshman, Thomas Picton, who had been wounded at Badajoz.

Sir James Leith, 1763-1816. Commanded the 5th Division at Salamanca and it was his attack which broke the centre of the French army.

In command of Wellington’s 4th Division was Sir Lowry Cole He was an experienced general who had seen service in the Peninsula since 1809. Cole had also been present at the battle of Maida in 1806 and thus had witnessed one of the earliest triumphs of the two-deep British line, a tactic which was to sweep Napoleon’s legions aside on several occasions. The 5th Division of the army was commanded by the 49-year old Scot, Sir James Leith, who had distinguished himself at the storming of Badajoz when his division successfully escaladed the San Vincente bastion.

One final word on Wellington’s commanders should be reserved for Gen. John Gaspard Le Marchant, the commander of the Heavy Brigade of Cavalry. Since the departure from the Peninsula in 1809 of Henry, Lord Paget – he had run off with Wellington’s sister-in-law – Wellington had been without a capable cavalry commander. The Allied cavalry gained a reputation for, as Wellington put it, ‘galloping at everything’, and had thus become something of a liability within his army. This uncontrollable urge to charge everything in their front on every occasion was demonstrated right up to the final battle of the Napoleonic Wars, Waterloo, on that occasion by the Union Brigade. Le Marchant, however, was a fine cavalry commander and has often been called ‘a scientific soldier’ on account of his training and knowledge of cavalry. His part in the battle of Salamanca was devastating although, ironically, tragic.

Marshal Andre Massena, duc d’Essling, 1758-1817. Wellington’s most dogged opponent in the Peninsula who served there between 1810 and 1811 before being recalled to Paris in May of that year.

General John Gaspard Le Marchant, 1766-1812. Le Marchant commanded the Heavy Cavalry brigade at Salamanca which demolished eight French battalions during its devastating charge. He was, however, tragically killed towards the end of the charge. One of the most influential soldiers of his age, Le Marchant designed the superb 1796-pattern light cavalry sabre and formed an accompanying system of sword drill.

The French army at Salamanca, the Army of Portugal, was commanded by the 38-year-old Marshal Auguste Marmont, Duc de Raguse. Marmont, a veteran fighter of several campaigns and ADC to Napoleon in 1796, had been appointed to command in Spain on 7 May 1811, replacing Marshal Massena. Marmont had spent his 12 months’ command marching and manoeuvring upon the Spanish–Portuguese border, but he had yet to fight a major battle in the Peninsula. Salamanca was to be his first and last.

Edward Pakenham 1769-1815. Pakenham commanded Wellington’s 3rd Division in the absence of Thomas Picton who had been wounded at Badajoz. Pakenham was killed in action three years later at New Orleans.

Marshal Auguste Marmont, Duc de Raguse, 1774-1852. Having superseded Massena the previous year, Marmont commanded the Army of Portugal at Salamanca but was badly wounded early in the action.

There were also several fine divisional commanders present, including Gen. Maximilien-Sebastien Foy, the 37-year-old veteran of Vimeiro who had been in the Peninsula since 1808, and who later wrote his own account of the war. Gen. Bertrand Clausel was another skilled commander who had seen widespread service and who had come to Portugal in 1809. The 44-year old Jean-Pierre-François Comte Bonnet, later to assume command of the army at Salamanca upon Marmont’s wound, had seen action throughout Europe and had lost an eye in 1793 at Hondschoote. Two other French generals who deserve a mention include Jean-Guillaume-Barthèlemy, Baron Thomières, a veteran of several battles in Italy and an officer of the Lègion d’honneur, who had been wounded at Vimeiro; and finally Antoine-François, Baron Brennier, wounded three times during his career, who had shown great skill in leading his garrison from the fortress of Almeida in May 1811 in the face of a British blockade, much to the annoyance of Wellington. Indeed, this incident is said by Wellington to have turned his victory at Fuentes de Oñoro into a defeat. Both of these last named men played significant roles at the battle of Salamanca.