The morning of 22 July dawned warm and sunny, which came as a welcome relief to the French and Allied troops after their soaking the previous night. The hot sun soon dried out the ground enough for clouds of dust to be kicked up by the two armies as they marched into position.

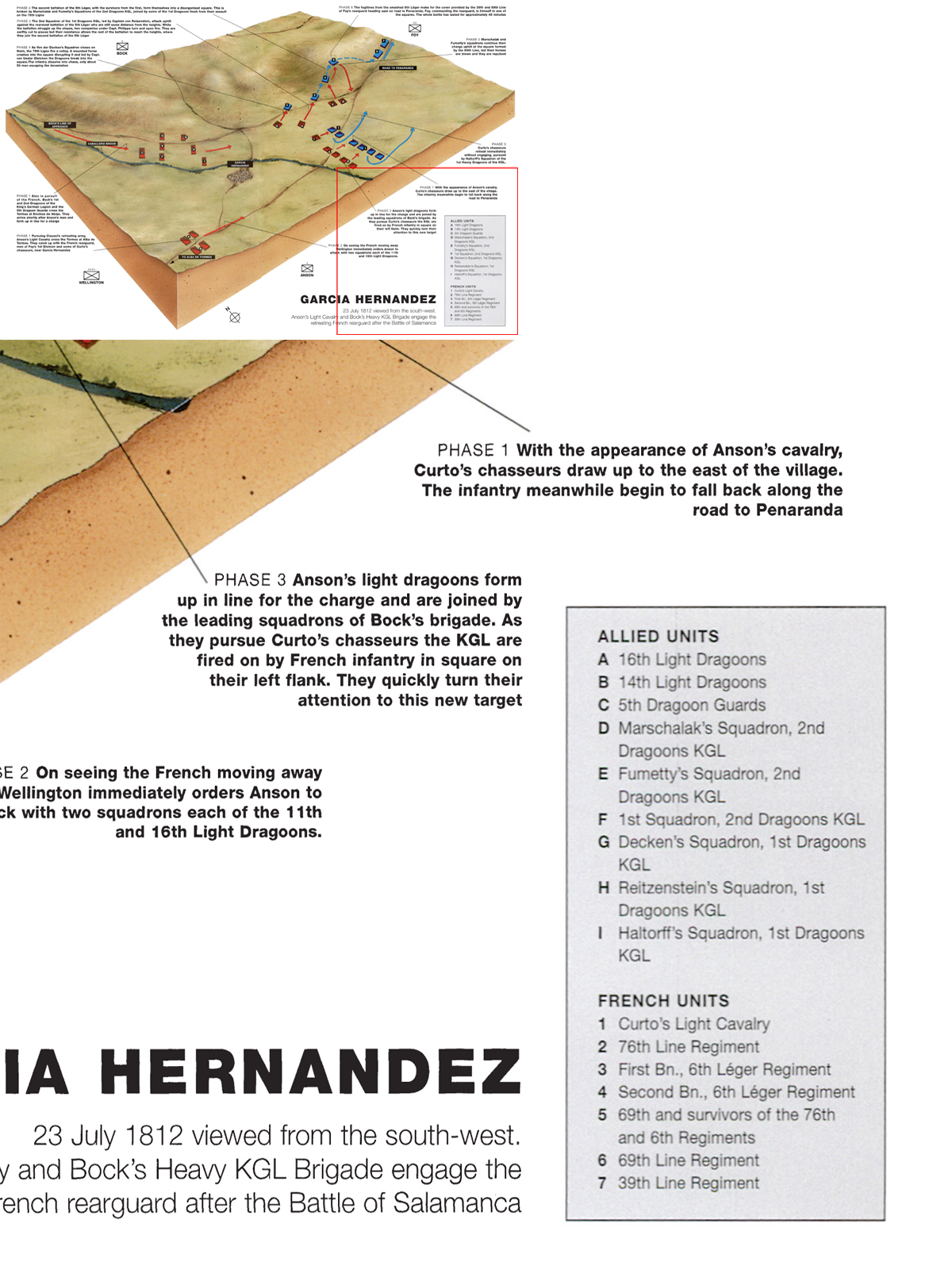

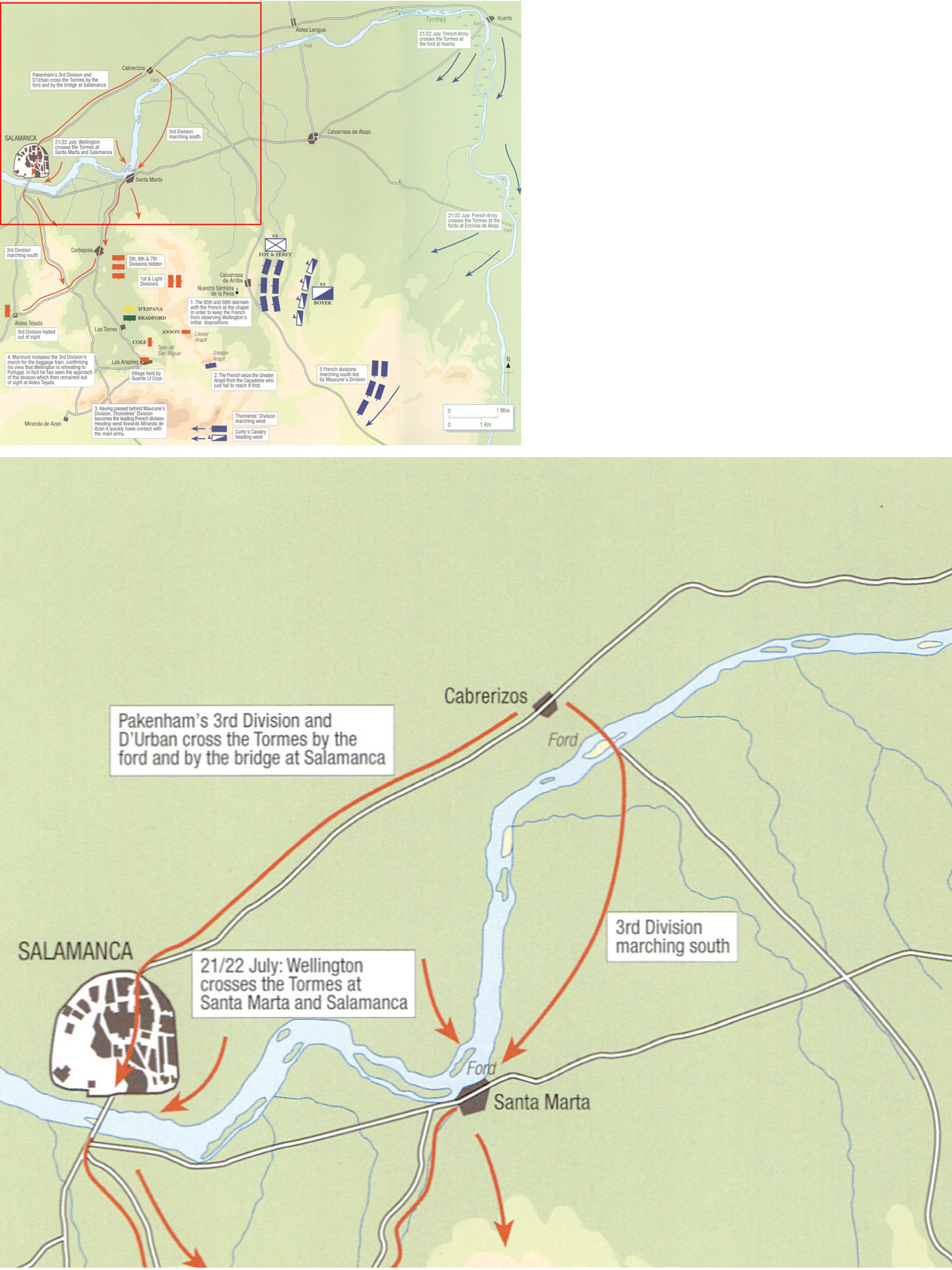

The Allied position extended from the River Tormes at Santa Marta on their left, along a range of heights running south to the Lesser Arapil. D’Urban’s cavalry and the 3rd Division were still on the north bank of the Tormes, watching the ford at Cabrerizos. Marmont occupied the ridge facing the Allies, stretching from the Tormes on the French right flank, to Calvarisa de Arriba on their left. Just in front of them lay the ruined chapel of Nuestra Senora de la Pena, occupied by some picquets of the British 7th Division, who were camped in some woods on the slopes to the west, with the 1st and Light Divisions in front. A valley or ravine separated the two heights, through which a small stream, the Pelegracia, flowed. During the morning Marmont began to bring the remainder of his army across the river and soon it began to move slowly south, his intention being to turn south-west and cut across the main road to Ciudad Rodrigo, Wellington’s line of retreat to Portugal.

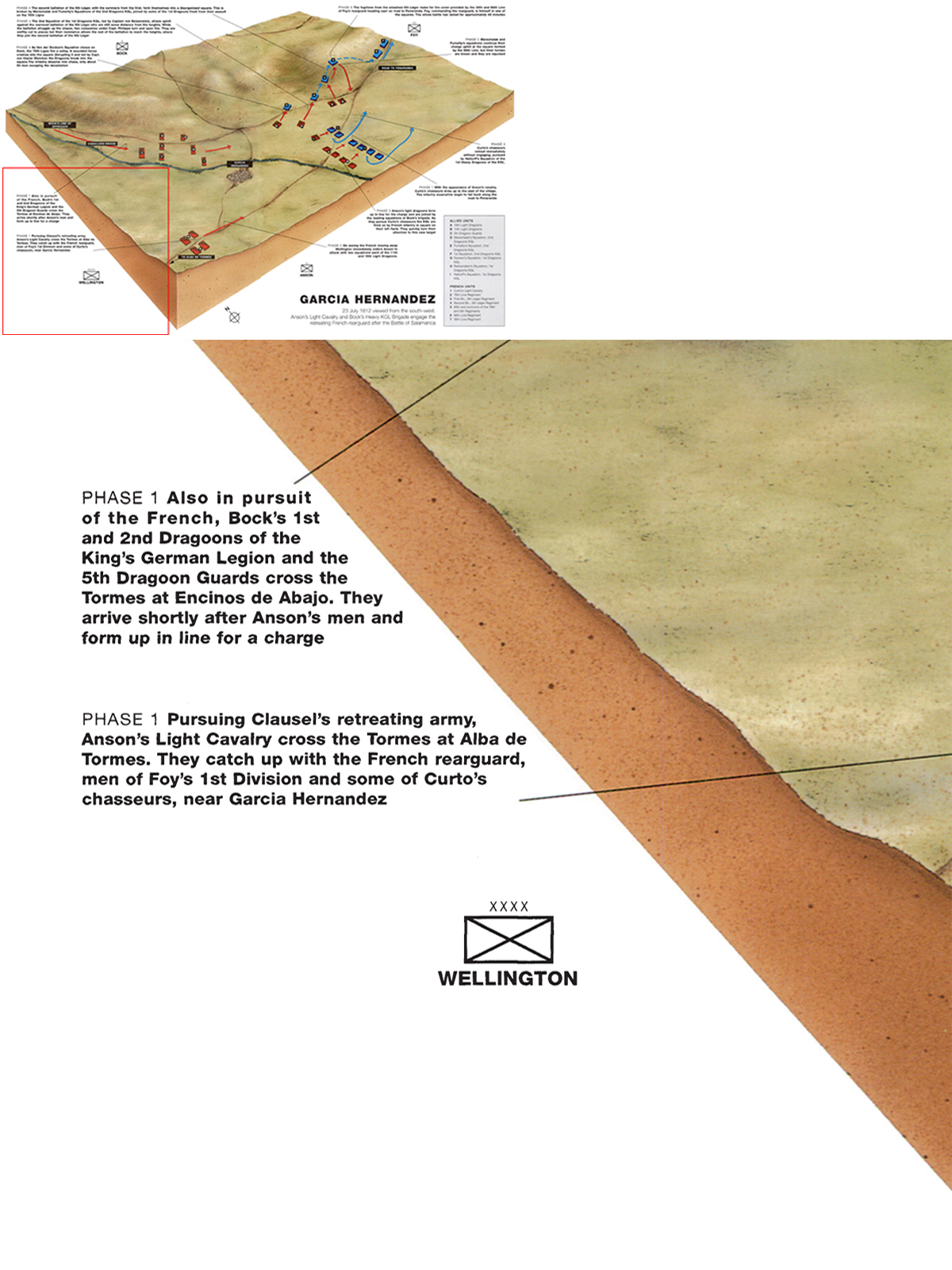

Having ridden frantically across from the village of Los Arapiles, Wellington joins his brother-in-law, Edward Pakenham, commanding the 3rd Division, and directs him to ‘drive everything before him to the devil’. (After a painting by Caton-Woodville)

The first skirmishing of the day took place at the ruined chapel, when Marmont, unhappy at having a British presence so close to his own position, ordered Foy’s voltigeurs to drive the British piquets back across the stream. Wellington countered this by sending forward the whole of the 68th and the 2nd Caçadores who drove the French back. This peculiar, isolated, episode took place a half-a-mile from the main Allied position, but perhaps demonstrates Wellington’s determination to screen his main force from the prying eyes of Marmont’s forward troops. The fight died down some time after noon, when both the 68th and 2nd Caçadores were withdrawn and replaced by some companies of the 95th Rifles, whom Marmont made no further attempt to drive off. Indeed, during the morning the 7th Division was pulled back from its position to join the 5th and 6th Divisions which were hidden from view close to the village of Carbajosa. Cole’s 4th Division, meanwhile, occupied a position on and around the Lesser Arapil.

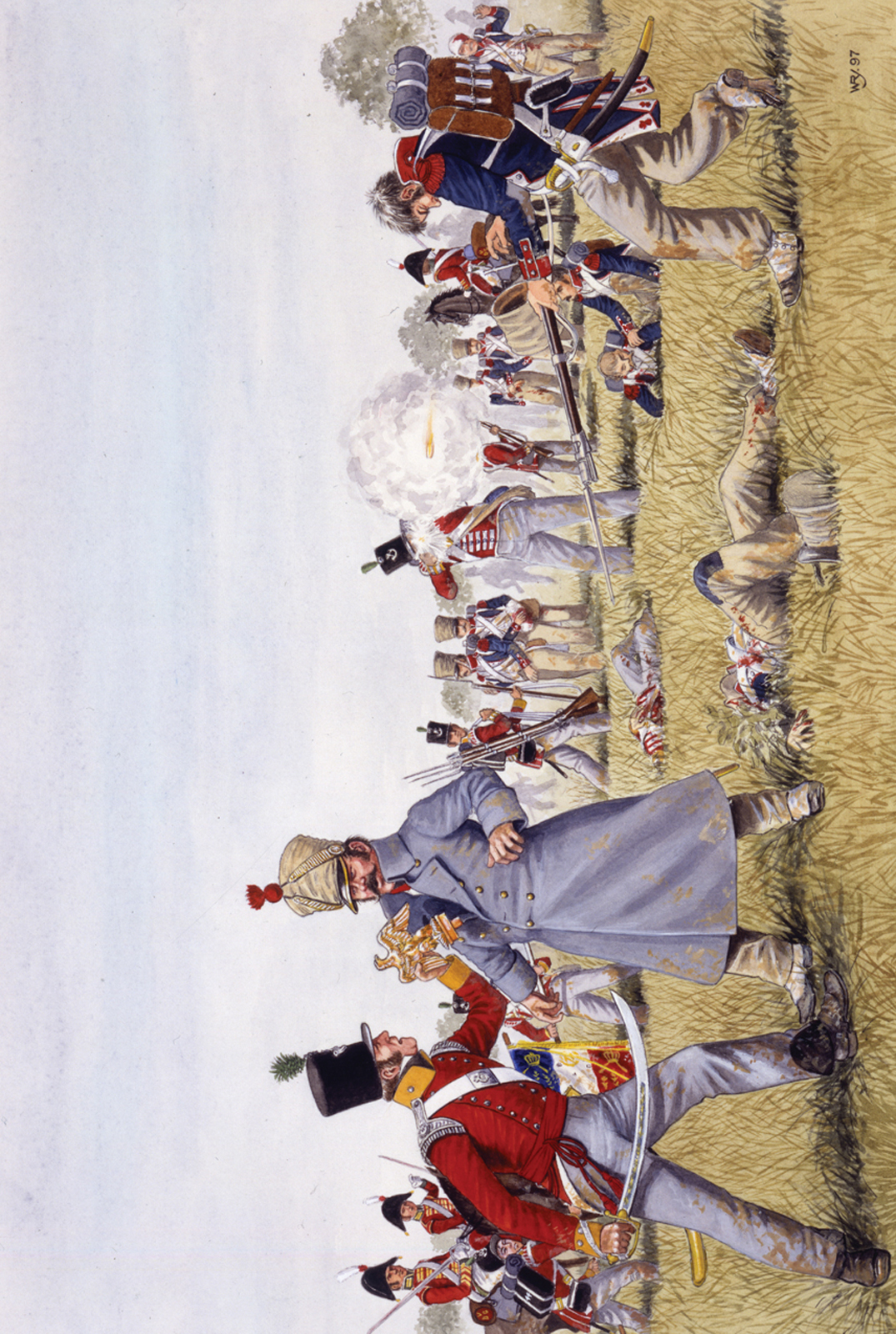

The 3rd Division smashing into Thomières’ division above Miranda de Azan on 22 July 1812, to begin the main action at Salamanca. Thomières was killed in the fight and his entire divisional artillery captured. As usual, anachronisms abound in Caton-Woodville’s painting, such as the bearskins worn by the grenadiers.

The battlefield area is dominated by two striking hills, known locally as the Hermanitos (‘two brothers’), or the Arapiles, as they are better known. The right flank of Wellington’s line rested upon the Lesser Arapil, a round hill about 100 feet high. This rugged hill is of easy ascent, and affords a good view of the surrounding area. About 600 yards to the south lies a much longer hill, the Greater Arapil. It is about 300 yards long and a few feet higher than the Lesser Arapil. Its northern face is fairly easy to climb, but the other sides are much steeper. Away to the south of the Greater Arapil lay an extensive wood which was later to provide the French troops with some sanctuary from the pursuing Allied army.

The Lesser Arapil itself is located at the hinge of an L-shaped range of hills which run north from the Lesser Arapil for about one mile, and west for a similar distance. The western hills are fairly low, unlike the northern branch which, towards the northern end, are fairly high in places. This L-shaped ridge lies within another, much larger L-shaped ridge which was to form the French position during the battle. The Greater Arapil formed the hinge of this ridge which ran north for about two miles and west for about three miles, as far as the village of Miranda de Azan. To the west of the two Arapiles hills lies the village of Los Arapiles itself, tucked away at the foot of a gradual slope which leads up to a ridge beyond which lay a wide valley, about 1,200 yards wide. The southern border of this valley was marked by another, slightly higher, ridge, which ran west as far as the village of Miranda. From the village to this ridge was a distance of about one mile. To the north of Los Arapiles lies the village of Las Torres and between the two, and just to the east of the former, is the hill of San Miguel, from which Wellington would observe much of the battle.

Wellington’s army initially occupied a position running north–south, facing Marmont’s army which was drawn up on the slopes opposite them with their left flank resting upon Calvarisa de Arriba. However, as the morning wore on it became obvious that the French were moving south, extending their left, and Wellington realised that he needed to occupy the Greater Arapil. His troops already held the Lesser Arapil, but in the half-light of the early morning he had not really appreciated the significance of the Greater Arapil whose bulky mass lay silhouetted further to the south. The occupation of both hills would have given him a position of great strength, providing two strong bastions which would be difficult to assault. Also, should the French attempt to march round his right flank they would have to negotiate the dense wood which lay to the south of the Greater Arapil. In the event, at around 8am, Marmont, seeing that the Greater Arapil was devoid of Allied troops, sent a body of skirmishers to occupy it at once, and there was a race between his men and the 7th Portuguese Caçadores, who Wellington had also sent forward. The French infantry proved to be too quick for the Portuguese, and after a swift but heavy exchange of musketry, the Caçadores were driven back. With the Greater Arapil in his hands Marmont began moving five of his divisions, those of Clausel, Brennier, Maucune, Thomières and Sarrut, to the wood which lay to the south. Here, the French assembled to await further orders, while Foy’s division remained at Calvarrasa de Arriba.

More British bearskins in action at Salamanca, 22 July 1812. Another French battery is about to be overrun in this painting by Caton-Woodville.

As the Greater Arapil was the pivot for Marmont’s army, so the Lesser Arapil proved the pivot for Wellington who, upon realising that the French were now in a position to threaten his right flank, altered his position. Leith’s 5th Division was brought about to face south on the right of Cole, still close to the Lesser Arapil, with Clinton’s 6th Division behind Cole, and Hope’s 7th Division in support of Leith, behind the village of Los Arapiles. The 1st and Light Divisions, meanwhile, were still in position running north–south and facing east opposite Calvarisa de Arriba. Indeed, these two divisions were to spend the day kicking their heels in frustration away from the main area of fighting, all, that is, except the light companies of the Foot Guards, which were brought up to defend the village of Los Arapiles. Coupled with this shift in position Wellington had ordered Pakenham’s 3rd Division and D’Urban’s cavalry to move to Aldea Tejada, just to the west of the Ciudad Rodrigo road, in order to support any Allied retreat or to act as an independent force, should the occasion for an offensive arise. These troops crossed the Tormes by the bridge at Salamanca and by the fords at Cabrerizos.

The 12th Light Dragoons charging at Salamanca, 22 July 1812. The Heavy Cavalry brigade naturally drew most praise for its conduct during the battle but the light dragoons did equally fine work on the day, and throughout the campaign as a whole. They are shown here wearing Tarleton helmets which were replaced later by the bell-topped helmet of which Wellington complained, it being very similar to that already worn by the French. After a painting by Granville Baker.

About an hour before noon, Marmont climbed to the top of the Greater Arapil and began scanning the Allied position. It is possible, even on a fairly hazy day, to see as far as Salamanca itself, the towers of the two cathedrals dominating the distant skyline. From his position Marmont would have been able to see most of the ground in rear of the Allied position. He would certainly have been able to see the ground between Los Arapiles and Las Torres (see the photograph on page 66). Hence, the 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th Divisions would have been visible, as would the 1st and Light Divisions, still facing east opposite Calvarisa de Arriba. The ground immediately behind the Lesser Arapil would have remained hidden, however.

Wellington and some of his staff at the battle of Salamanca, 22 July 1812.

Marmont was obviously under the impression that Wellington was in retreat towards Ciudad Rodrigo. Indeed, the Allied baggage train had already been reported moving off along the road, and his supposition appeared to be confirmed when clouds of dust were seen in the distance leaving Salamanca at speed in the same direction.

Marmont’s first conclusion was that Wellington was mustering his troops for an attack on Bonnet’s division, which occupied the ground around the Greater Arapil, and was somewhat isolated from the other French divisions. In fact, Wellington himself had considered such a move and apparently ordered the 1st Division to be brought to a state of readiness. However, Beresford persuaded him to abandon the idea. Unfortunately for Marmont, this was to be only a temporary reprieve as the blow, when it did come a few hours later, was to prove even more decisive.

The day wore on and still there was no action, other than the occasional crackle of musketry from the heights around Nuestra Senhora de la Pena, as the British and French piquets sniped at each other. Marmont, meanwhile, continued to gaze out from the Greater Arapil and saw clouds of dust rising in the west, the ground having been thoroughly dried out by the hot sun. There was no doubt in his mind: Wellington was retreating. At about 2pm, therefore, his army lumbered into motion and began moving slowly westwards across the low heights in front of it. This range of heights stretched for about three miles as far as the village of Miranda de Azan. Stretching away beneath them was an undulating plain, about a mile wide, at the foot of which lay the village of Los Arapiles. Marmont’s intention was to sever the road to Ciudad Rodrigo and fight Wellington with his army penned in against the Tormes with Salamanca at his back. It seemed quite simple.

The clouds of dust thrown up by Wellington’s men did not mark the trail of a retreating army, however, for they were caused by the tramping feet of some 3,600 men of Pakenham’s 3rd Division, as well as D’Urban’s 482 cavalry. By 2pm Pakenham had reached his position at Aldea Tejada, just to the west of the Ciudad Rodrigo road and halted in a fold in the ground, hidden from view from all but those Allied officers on the highest point of Wellington’s main position. Wellington’s army was now arrayed in battle order, forming an L-shape, with the 1st and Light Divisions facing east, and the 4th, 5th, 6th and 7th Divisions facing south, with Pakenham’s 3rd Division hidden away at Aldea Tejada.

British and French infantry clash at Salamanca. The British troops are shown incorrectly wearing the 1812 Belgic shako, which was rarely worn, if at all, in the Peninsula. The town itself can be seen in the background, much closer to the battlefield than it actually is. After a painting by Simkin.

The ‘Jingling Johnny’, captured from the French 101st Regiment by the 88th (Connaught Rangers) at Salamanca.

Marmont’s divisions, meanwhile, were on the move, noisily engaged in what they assumed was a resumption of the race which had been run throughout the last few days of manoeuvring north of Salamanca. The leading French division, Maucune’s, halted at a point opposite Los Arapiles. Skirmishers went forward to the southern edge of the village, while Maucune’s guns opened fire on the village itself and the slopes behind. This artillery fire was returned by the guns of Sympher’s battery of the 4th Division and by two guns atop the Lesser Arapil. These latter guns were quickly silenced, however, by French artillery which had been manhandled to the top of the Greater Arapil. Maucune had marched west with the divisions of Thomières and Clausel in support. However, Thomières, instead of merely halting his division behind Maucune, passed to the rear of him and continued marching towards Miranda de Azan. In fact, Marmont’s left wing was disappearing away to the west without any support from the French centre or right.

The potentially disastrous manoeuvre was not lost on Wellington when he was told of it. The story of Wellington’s ‘Salamanca lunch’ is almost as well known as the outcome of the battle. While the Allied commander-in-chief was ‘stumping about and munching’ on a piece of cold chicken, an aide-de-camp suddenly came racing into the courtyard of the farm, and told him that the French were extending to their left. The accounts of just what happened next vary. Wellington is often reported as throwing the leg of chicken over his shoulder before leaping on his horse to take a look for himself. He is also quoted as exclaiming either ‘By God! That will do!’, or ‘The devil they are! Give me the glass quickly’. Whatever the truth, there can be little doubting his rush of excitement when he saw Thomières’ error. A brief look through his telescope was enough and, snapping it shut, he turned to Gen. Alava, his Spanish liaison officer, and said calmly, ‘Mon cher Alava, Marmont est perdu.’

Royal Horse Artillery teams coming into action in the Peninsula. The RHA troops of Ross, Macdonald and Bull were present at Salamanca. It was a shell fired from one of Dyneley’s guns on top of the Lesser Arapil which severely wounded Marmont.

So, what exactly had Wellington seen? Well, from his position on the Teson de San Miguel, just to the east of the village of Los Arapiles, he could see quite clearly Maucune’s division as it halted on the heights immediately to the south of the village. Behind Maucune, Thomières’ division was continuing its march west towards Miranda de Azan, while Clausel’s division, sent to support Maucune, had stopped after debouching from the woods to the south of the Greater Arapil. The main error was being committed by Thomières who, instead of halting in support of Maucune, continued his march west, imagining a resumption of the ‘race’ of the previous few days. Before too long a considerable gap had opened between his division and that of Maucune. With the French columns strung out along the heights in front of him, Wellington knew that his moment had come – and he was quick to seize it.

Wellington was soon in full flight, riding towards Aldea Tejada, where Pakenham’s 3rd Division and D’Urban’s cavalry had arrived unseen at about 2pm. Such was the speed of Wellington’s ride – he was an accomplished horseman – that it is said he rode alone for the greater part of the three miles, with his staff trying desperately to keep up with him. It was 3.45pm and it must have been a very dramatic scene as the lone horseman came galloping across the dry, dusty ground with the eyes of every man of the 3rd Division strained anxiously upon him. Wellington found the 3rd Division waiting patiently in their ranks with Pakenham at their head. The commander-in-chief rode up to Pakenham, his brother-in-law, and said simply, ‘Edward, move on with the 3rd Division, take those heights in your front, and drive everything before you.’ ‘I will, my Lord,’ replied Pakenham, at which the two men shook hands before parting. Having given the 3rd Division its orders, Wellington turned about and a few minutes later was doing the same to Leith’s 5th Division. This is a prime example of Wellington’s method of command, and his unwillingness to delegate responsibility to others. Perhaps on this occasion, he recognised the importance of the task given to Pakenham and was not prepared to risk his orders being incorrectly delivered by an aide.

British heavy dragoons in action at Salamanca. Note their old cocked hats, still worn at the time, prior to their replacement by the crested helmet. A negro trumpeter in a white uniform can be seen at left.

The battle of Salamanca. Wellington, right, receives news of the attack as his divisions advance in line in the distance.

The battle of Salamanca. Wellington looks on as his infantry opens its ranks to let Le Marchant’s Heavy Cavalry through.

While Pakenham’s division moved off towards Miranda de Azan, Wellington was riding back towards the Allied divisions mustered behind the Teson de San Miguel. En route, orders were despatched to Arentschildt, who was ordered to join D’Urban covering Pakenham’s division, and to Bradford, Espana and Cotton, all of whom were soon on the move in support of Leith. Leith, in fact, was the first to receive his orders when Wellington arrived at the Teson de San Miguel. Upon the arrival of Bradford’s Portuguese brigade on his right, Leith’s 5th Division was to advance over the Teson and attack Maucune’s division which was still on the heights above Los Arapiles. All being well, when Leith attacked he should be able to see Pakenham further to the west as the 3rd Division struck home against Thomières. On Leith’s left, meanwhile, Cole was ordered to attack with the 4th Division.

British cavalry in action at Salamanca, while a French officer protects an Imperial Eagle, at right.

A short time afterwards, the light companies of both the 4th and 5th Divisions, as well as Pack’s Portuguese brigade, were stretching out into the Arapiles Valley and were soon making their way towards the crest of the ridge opposite to open fire against their French counterparts. Meanwhile, the main bodies of these units scrambled to their feet to await the order to advance. This, of course, exposed them to the fire of the French artillery, the British and Portuguese having spent the afternoon lying down. This punishment continued for some 40 minutes or so as Leith, Cole and Pack waited for Bradford to come up. Finally, Bradford’s Portuguese arrived and the moment had come for Wellington’s masterstroke.

Officer and riflemen of the 95th Rifles. Probably the most famous British regiment of the Peninsular War, it nevertheless played very little part in the victory at Salamanca.

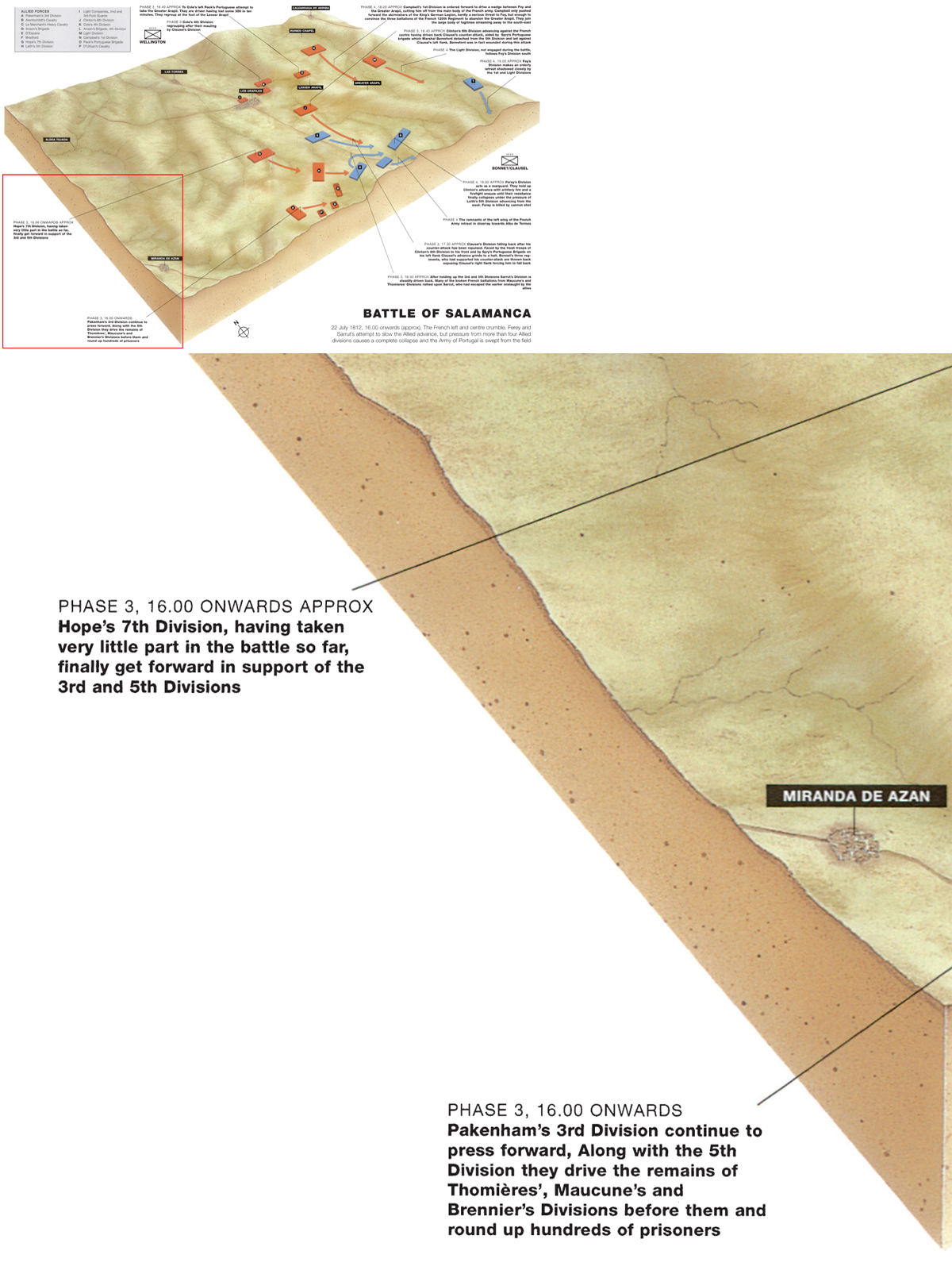

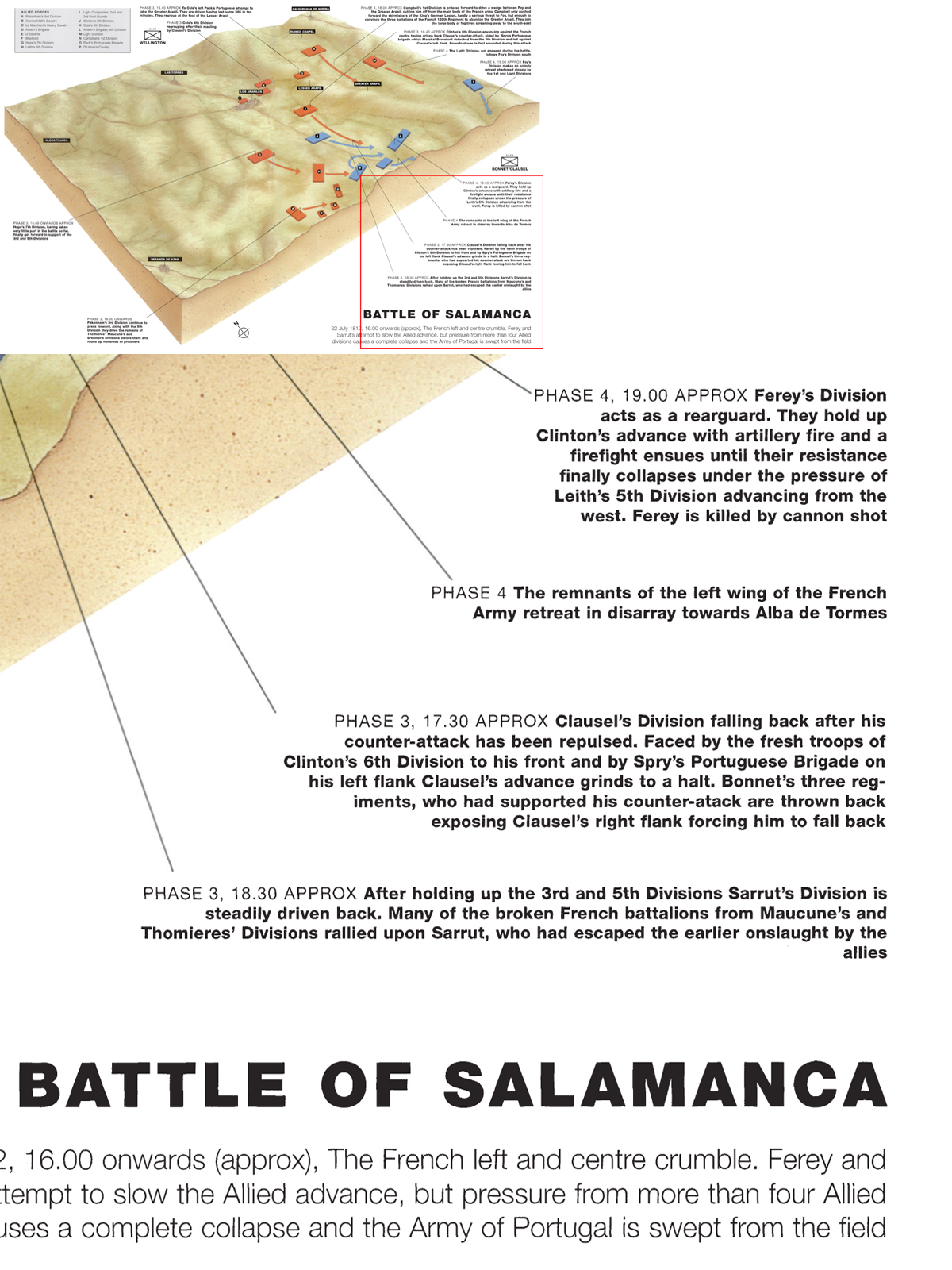

It will be easier to follow the battle of Salamanca by beginning with the first action of the afternoon, at Miranda de Azan, and with Pakenham’s devastating attack on Thomières’ division. However, between 3pm and 4pm the French army lost its commander-in-chief. As Marmont gazed out to the west to watch the progress of his divisions he suddenly realised, to his horror, that not only was Maucune far too close to the village of Los Arapiles, but that Thomières’ division, which should have been in support, was pressing too far to the west. Marmont quickly saw the dangerous gap which had appeared between the two divisions and knew that Wellington had only to cross the Arapiles valley and the day would be as good as his. It is somewhat ironic that for once, Marmont appeared to take a leaf out of Wellington’s book and decided to come down from the Greater Arapil in order to ride away and take charge of his left wing himself, rather than simply send an order to Thomières to halt via an aide. However, whereas Wellington was able to give his crucial order in person to Pakenham, Marmont was injured as he scrambled down the steep side of the hill by a British shell and left with a serious wound to his arm and ribs. Indeed, the rumour, false as it turned out, went round the British ranks after the battle that he had been killed. With Marmont carried from the field, command passed to Bonnet but, with a singular stroke of bad luck, he too was wounded afterwards, and by 6pm the French army had its third commander of the day, Clausel.

Upon receipt of Wellington’s order to advance, Pakenham had formed his division into four columns, the outer two consisting of D’Urban’s cavalry, the third made up of Wallace’s and Power’s brigades, and the fourth column of Campbell’s brigade. The division marched in column of lines, a formation which, when the time came, would allow it to form into line without halting. Pakenham’s advance, of some two and a half miles, was hidden from the enemy’s view by a low range of wooded hills to their front. Thomières was completely unaware of the advancing 3rd Division, and had not even taken the precaution of protecting his column with cavalry. Indeed, Curto’s light cavalry division which accompanied him appears to have ridden parallel with the centre of the French column, rather than at the head of the column or on its flank. D’Urban himself had ridden on ahead with two ADCs and, peering through some trees, saw that the head of Thomières’ division was passing across the right flank of Pakenham’s division, which was marching obliquely across Thomières. D’Urban rode back and, gathering his three Portuguese cavalry squadrons about him, with the 11th Portuguese and two squadrons of the 14th Light Dragoons in support, swept from the cover of the trees and charged in among the foremost French company. Two squadrons of the Portuguese dragoons suffered considerably from French fire, but the third squadron, falling upon the unformed left flank of the French column, charged home with some success and broke a whole battalion. The attack had the desired effect of driving the head of the column back upon its succeeding files but, more significantly, it alerted Thomières to the perilous, not to say fatal, situation in which he suddenly found himself.

THE ATTACK BY LEITH’S 5TH DIVISION

At about 16.40 Leith’s 5th Division, after enduring a prolonged period under fire from French artillery, began its attack on Maucune’s division above the village of Los Arapiles. The 5th Division advanced with Greville’s brigade in front, the 3/1st, 1/9th, the 2/30th and 2/44th, and Spry’s Portuguese, the 3rd and 15th Lines. When the 5th Division reached the crest of the heights they found Maucune’s division drawn up in squares, probably due to the fact that they could see Le Marchant’s cavalry advancing on Leith’s right flank. In the ensuing contest the British firepower broke the squares and caused the French to break formation, just as Le Marchant’s cavalry arrived to complete the rout.

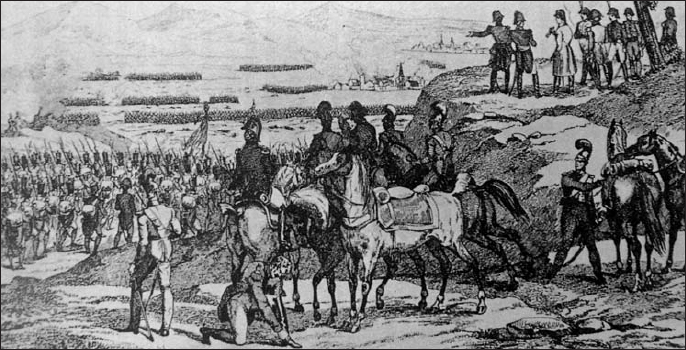

The battle of Salamanca, 22 July 1812. This somewhat stylised engraving shows the battle from the French perspective. Salamanca can just be seen in the distance with the village of Los Arapiles in the centre. Wellington’s divisions can be seen in the distance in line.

Thomières’ division was strung out along the heights running east from the summit of the Pico de Miranda for a distance of some 2000 yards. His division consisted of three regiments, the 101st, 62nd and the 1st, numbering some eight battalions between them, marching one after the other but with dangerous intervals between them. As if the appearance of D’Urban’s cavalry on his flank was not enough to send him into a near panic, Thomières’ blood must surely have been chilled by the sudden appearance of Pakenham’s ‘Fighting’ 3rd Division, probably the most fearsome division in the whole of Wellington’s fine army. Pakenham’s men burst from the trees opposite the Pico de Miranda at a distance of around 500 yards. The oblique advance of Pakenham’s men, coupled with their formation in three columns, enabled them to deploy without having to halt. They simply brought up their right shoulders and in a few moments had formed a line from open column, with Wallace’s brigade leading.

The small chapel of Nuestra Senhora de la Pena. The chapel lay a mile and a half in front of Wellington’s initial position on 22 July. It was occupied by piquets of the 7th Division for a time and was the scene of the early fighting on 22 July involving the 68th, 2nd Cacadores and the 95th Rifles.

As soon as Thomières and his men recovered from the shock of having clashed with Allied cavalry, he ordered some 20 guns to be brought forward along the top of the crest towards which the 3rd Division was advancing. These guns began to take their toll on Pakenham’s men who advanced into the fire of grape and round shot. At the same time, Curto’s light cavalry division finally got into the action, charging in on the right flank of Pakenham’s line where the British 1/5th attacked, suffering 126 casualties. Fortunately, Arentschild’s hussars were thrown into the fray, breaking their French adversaries and sending them back upon their own lines. By now British skirmishers were beginning to swarm up the hill to the summit of the Pico de Miranda where they were met half-heartedly by a more numerous French skirmish line whose fire was somewhat ineffective. Thomières’ guns, however, took a much heavier toll of the Allied infantry, although this fire was in turn answered by the divisional battery of Douglas’s 3rd Division, which began to send shot up the hill against the French right.

An unusual view of the two Arapiles looking south-west from the initial French position on the morning on 22 July. The Greater Arapil is visible on the skyline to the left, with the Lesser Arapil on the right. Wellington’s initial position ran behind the skyline on the right of this photo. Marmont’s army would have moved from right to left across the immediate foreground to sweep south to gain the Greater Arapil. They then turned west to form the ‘L’ shaped line which caused Wellington to shift his position also.

The French skirmishers were sent reeling back upon the main body of the French column which struggled to deploy on the crest of the Pico de Miranda, a task made yet more difficult by the ominous and determined advance of Wallace’s brigade which grew closer by the minute. They did, however, manage to get off one effective volley which hit scores of Connaught Rangers, but still the 88th came on, their steady, determined advance causing an unsettling effect within the French ranks. When Major Murphy, commander of the 88th, was shot dead in front of his men there was no holding them. Seeing Murphy’s lifeless corpse being dragged along by his horse, the 88th were whipped into a fury and when Pakenham, shouting to make himself heard above the din, gave the order to ‘let them loose’, they launched a frenzied attack on their French adversaries who paid a terrible price for the death of the 88th’s officer.

Another view of Wellington’s initial position as seen from the chapel of Nuestra Senhora de la Pena. Wellington’s troops were positioned on the reverse slope of the ridge in the distance. The 1st and Light Divisions remained here during the battle watching Foy’s division.

The long, box-shaped hill on the right is that behind which Pakenham’s 3rd Division halted at Aldea Tejada. The village itself lies behind the hill and it was from here, across the foreground, that the 3rd Division advanced. The woods, present in 1812, have completely gone.

Indeed, such was the fury of Wallace’s attack that Thomières’ division crumbled quickly. Thomières himself was killed and his entire divisional battery was captured. The 101st Ligne lost 1,031 out of 1,449 men, while the 62nd Ligne lost 868 out of 1,123. The rear regiment suffered least of all, losing just 231 men out of 1,743. Before long, the shattered remnants of Thomières’ division were tumbling back in panic to the east, falling back before Pakenham’s cheering brigades upon Maucune’s division which itself was about to be demolished.

The Pico de Miranda, as seen from the approach of Pakenham’s 3rd Division. This hill represents the limit of Thomieres’ march, prior to the attack of the 3rd Division. Pakenham’s men attacked up these slopes, probably from right to left, to begin their devastating rout of the French.

The village of Miranda de Azan, as seen from the Pico de Miranda. It was on these barren hills that Thomieres’ division was smashed by Pakenham’s 3rd Division which swung round to attack from right to left.

At around 4.15pm, some 45 minutes after Pakenham had begun his attack, Leith’s 5th Division got to its feet behind the Teson de San Miguel to begin its attack. The order was greeted with relief by the men who must have been relieved that their ordeal at the hands of French artillery would soon be at an end. Indeed, Leith himself had spent much of the afternoon riding up and down among his men encouraging them in the face of the pounding enemy artillery. Even so, they still had to wait for Bradford’s Portuguese to come up on their right flank before they could begin any forward movement. Finally, Bradford arrived and the order was given for the advance to begin. The men of the 5th Division began filing through the narrow streets of Los Arapiles, and to the right of the village, having formed two long lines beforehand. The first line consisted of Greville’s brigade, the 3/1st, 1/9th, the 1/38th and 2/38th, as well as the 1/4th from Pringle’s brigade. The second line was made up of the rest of Pringle’s brigade, the 2/4th, 2/30th and 2/44th, along with the 3rd and 5th Line of Spry’s Portuguese brigade. As the long lines of Allied infantry set out towards the French positions on the crest above the village, Wellington himself rode between them before retiring to leave the task to Leith.

A view of the two Arapiles hills from the Teso de San Miguel. The Lesser Arapil is visible to the left and the Greater to the right. The Teso de San Miguel was Wellington’s viewpoint for much of the battle.

The roman bridge over the Tormes at Salamanca. Part of Pakenham’s 3rd Division marched across this bridge to Aldea Tejada on 22 July. French prisoners were also marched across it into town after the battle.

The advance of Leith’s 5th Division must have been as impressive as it was relentless, the men striding forward in the face of a heavy enemy fire, from both French skirmishers and artillery. Leith’s own skirmishers threw themselves forward, and slowly but steadily pushed back those of the enemy who withdrew from the slopes in front of the heights to the crest itself, while the French guns also pulled back. In fact, Maucune pulled his men back to a position on the reverse slope of the crest, as if aping Wellington’s own favoured strategy, and yet the French failed to make the tactic work in the same way. Maucune’s columns apparently formed themselves into squares, perhaps because they were aware of Le Marchant’s heavy cavalry which must have been visible to mounted French officers. The French infantry squares waited some 50 yards behind the crest, anxious fingers twitching on triggers, while all the time the sound of Leith’s relentless advance carried from the other side of the ridge. At last, the Allied infantry came into sight over the ridge and then, at the word of command, the French let loose a single volley followed, a moment later, by a volley from Leith’s men. The crash was tremendous. One of the first to come reeling back through the smoke was Greville, commanding the leading brigade; his horse had been shot through the head, and its body fell pinning its rider to the ground. Leith himself was badly wounded, while scores of men on both sides fell amid the storm of musketry. In spite of initial French resistance, the contest was quickly decided by the bayonet-wielding British infantry who, with a wild cheer, lowered their steel and rushed at their adversaries who dissolved into a panic-stricken mass of fleeing men.

THE 3RD DIVISION’S ATTACK AT MIRANDA DE AZAN

The battle of Salamanca opened at the Pico de Miranda, a hill slightly to the north of the village of Miranda de Azan. Thomières’ division had outpaced the main French columns until it had become separated by about a mile from the next division, Maucune’s. Pakenham’s 3rd Division had marched unseen from Aldea de Tejada in four columns. By bringing up their right shoulders they were suddenly in line before bursting out from the cover of the trees which had hidden their advance. They attacked uphill against the surprised French who barely had time to form. The attack was a devastating success for the 3rd Division who swept over the French, capturing the divisional artillery and killing Thomières himself. Pakenham then led his division east, pushing the remnants of Thomières’ division before him.

A view of the main fighting area at Salamanca, as seen from the top of the Greater Arapil. The village of Los Arapiles can be seen away to the right. Cole’s 4th Division attacked from right to left across the immediate foreground, whilst Leith’s 5th Division attacked south out of the village itself. The damage wrought by Le Merchant’s Heavy Cavalry brigade was roughly where the dark patch on the left horizon is.

Wellington’s viewpoint from the Teso de San Miguel, looking south across the Arapiles valley. The village itself is on the right whilst Thomières and Maucune moved across the skyline from left to right.

Bradford’s Portuguese troops had advanced to the crest on Leith’s right and, coming into action against the extreme left flank of Maucune’s division, had avoided much of the punishment meted out to the 5th Division during its advance. Bradford, in fact, had met with little opposition and simply joined in the pursuit of Maucune’s fleeing infantry. Even further to the Allied right could be seen Pakenham’s triumphant 3rd Division which was driving the shattered remnants of Thomières’ division before it.

The 5th Division, meanwhile, pressed on against Maucune whose squares had been devastated by Allied firepower. Ironically, this particular formation, most unsuitable for facing enemy infantry, was what was now required by Maucune more than anything else, because pouring over the crest of the ridge, roaring like a burst of thunder, came every fleeing infantryman’s worst nightmare – enemy cavalry. What was worse, these cavalrymen, some 1,000 in all, were the men of Le Marchant’s heavy cavalry brigade, the 5th Dragoon Guards, with the 3rd and 4th Dragoons. They were armed with long, straight swords, capable of inflicting terrible wounds upon enemy infantry; nowhere was the power of the 1796-pattern heavy cavalry sword more clearly demonstrated than at Salamanca.

Le Marchant’s men had been waiting patiently close to the village of Las Torres where Wellington himself had issued Le Marchant with his orders. He was to ‘charge in at all hazards’ as soon as Leith’s infantry had engaged the French at the crest. The commander of the heavy brigade needed no such explanation of this order, and once Leith’s battalions reached the crest of the ridge above Los Arapiles he formed his men into two lines, the 5th Dragoon Guards and the 4th Dragoons in front, with the 3rd Dragoons in the second line. At 4.45pm the three regiments charged forward, passing Bradford’s division on their right, and swept round the right flank of Leith’s division, whose men turned and cheered as the dragoons emerged from thick, choking clouds of dust and smoke. As the dragoons rode over the top of the crest they found Maucune’s beaten battalions falling back in the face of Leith’s onslaught. It was the perfect scenario for Le Marchant and for the much-maligned British cavalry to prove that they were capable of delivering the sort of blow that had eluded them since the days of Sahagun and Benavente.

A French view of the main fighting area at Salamanca. The Greater Arapil is on the right and the Lesser on the left. Thomieres’ and Maucune’s divisions both passed across the foreground heading west. Both Leith’s and Cole’s divisions fought here, with Cole’s division advancing nearer to the Greater Arapil.

Le Marchant struck at the brigade on Maucune’s left and caught two battalions of the 66th Regiment rolling backwards. The French made a desperate attempt to form themselves into a defensible formation, but before they could do so the heavy dragoons were among them, cutting and hewing all around. The two battalions were all but annihilated, hundreds throwing down their arms in surrender, while the survivors fled to the woods to the south-east. The 15th Line were next to feel the full fury of Le Marchant’s men and, like the 66th, were soon in full flight towards the woods. As Maucune’s battalions streamed away from the field, Brennier’s division hurried to their assistance. Indeed, his leading regiment, the 22nd Line, formed up and unleashed a withering volley into the ranks of Le Marchant’s leading squadron, of the 5th Dragoon Guards, who were leading what was by now a brigade which had become mixed together. In spite of the destructive effect of the volley the dragoons could not be stopped and once again they crashed into the ranks of the French infantry. An almighty struggle ensued as the French defended themselves desperately with their muskets against the awesome British broadsword. Indeed, the French only gave way after some fierce fighting on the part of the dragoons who by now had lost all formation. Sadly, their devastating charge was to end in tragedy. Le Marchant, riding with just half a squadron of the 4th Dragoons, came up against the fugitives on the edge of the wood, one of whom levelled his musket and fired, killing Le Marchant. It was his first major action and Wellington’s army was thus deprived of one of the painfully few cavalry officers who knew their business. His brigade had done its job, however, and when the exhausted heavy dragoons gave up the pursuit they could reflect upon the fact that they had destroyed some eight battalions of French infantry 1,500 French prisoners were taken by the 5th Division, while five guns were captured by the 4th Dragoons. They seized the eagle of the 22nd Line and that of the 62nd Regiment, which was taken by Lt. Pearce of the 44th (East Essex) Regiment, one of Pringle’s battalions.

From the elevated position of the camera, this picture gives little idea of the height on the right of this picture. It is, however, the ridge over which Leith’s 5th Division attacked to find Maucune drawn up in square formation. Le Marchant’s cavalry would have charged over this ridge to find the French waiting obligingly for them in this valley. The 3rd Division, meanwhile, would soon be pushing in along the heights in the distance heading south-east. It was somewhere in this valley that Lieutenant Pearce, of the 44th (East Essex) Regiment, captured the ‘eagle’ of the French 62nd Regiment.

THE CAPTURE OF THE EAGLE OF THE 62ND REGIMENT

As the men of Leith’s division rounded up prisoners from Maucune’s division following the combined attack by Leith and Le Merchant, Lieutenant Pearce, of the 44th Regiment, saw a French officer attempting to hide the eagle of the 62nd Regiment, which he had unscrewed from its pole, beneath his greatcoat. Pearce demanded the officer hand it over, whereupon a French soldier levelled his bayonet at him, only to be shot by a man from Pearce’s company. Pearce carried the eagle off in triumph and it can be seen on page 64.

The western half of the battlefield was a mass of confusion, but must have presented a very pleasing sight for the Allied army as thousands of beaten Frenchmen streamed away to the south-east with Leith’s triumphant 5th Division pushing ever forward. The 3rd and 5th Divisions swept across the battlefield, driving the remains of Thomières’ Maucune’s and Brennier’s divisions before them, while D’Urban’s and Arentschildt’s cavalry charged every now and then against any French infantry that attempted to make a stand.

The front and back views of the Imperial Eagle of the French 62nd Regiment, captured by Lieutenant Pearce of the 44th (East Essex) Regiment.

In fact, there was some sharp fighting between the two armies’ cavalry during this period of the battle. Curto’s light cavalry brigades inflicted some damage against isolated parties of Le Marchant’s brigade, while the 3rd French Hussars drove back the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion, who were busy herding in French prisoners, and were only beaten back themselves after a hard fight.

With the left wing of Marmont’s army dissolved, Wellington might have thought the battle as good as won. However, in the centre of the battlefield things were not going so well for him. In fact, the French almost staged a remarkable comeback. About 20 minutes after Leith’s 5th Division began its advance, Cole’s 4th Division moved forward across the valley to attack Clausel’s division. The division advanced with Ellis’ brigade on the right and Stubbs’s on the left, with the 7th Caçadores acting as a thick skirmish line. As with the 5th Division, Cole’s men suffered during their march from enemy artillery fire, but soon they were ascending the heights upon which Clausel’s men were drawn up. Five French battalions engaged five British and Portuguese battalions and within a few minutes the two sides found themselves locked in a furious firefight which must have rekindled memories of Albuera for the fusiliers of Ellis’s brigade. The French were driven back some 200 yards, but Cole’s men found themselves dangerously exposed, as their attack lost its impetus and Cole himself was badly wounded. Their somewhat perilous situation was due mainly to the failure of Pack’s attack on the Greater Arapil on Cole’s left flank.

The rocky ledge at the top of the Greater Arapil. It was here that Pack’s Portuguese troops were forced to lay down their muskets in order to climb over the chest-high ledge, at which point the French 120th Regiment stepped forward and drove them back with a devastating volley.

Pack had watched the 4th Division as it purposefully strode forward towards Clausel’s division and realised that Cole’s left flank would be exposed to an attack from Bonnet’s troops who were waiting at the foot of the Greater Arapil. Once Cole had engaged Clausel these troops would, in effect, be in Cole’s rear. Therefore, Pack took the decision to move against the Greater Arapil himself with his Portuguese brigade. Wellington, in fact, had previously instructed him to attack if the opportunity arose. That opportunity had now arrived and Pack grasped it - although the outcome was not as he would have wished.

Pack threw out the 4th Caçadores to act as skirmishers, while the Portuguese 1st and 16th Lines followed behind in two columns. Pack had decided to make a direct assault on the northern slopes of the Greater Arapil. The Portuguese made good progress and drove back the French skirmishers opposed to them. Their march continued up the slopes of the Greater Arapil to the flat-topped summit where, just a few feet below it, their advance was halted by a rocky ledge of some five feet or so which had to be negotiated first. The Portuguese infantrymen threw down their muskets and began to climb over the ledge, whereupon the French 120th Regiment, who had been waiting at the top, stepped forward and unleashed a devastating volley into the ranks of the Portuguese who were in no position to make any effective resistance. Pack’s men were flung from the top of the Arapil and down the slopes with the jubilant French in hot pursuit. Some 386 Portuguese were lost in just ten minutes in their brave attempt to support the 4th Division. With Pack’s brigade having been driven back all the way to the Lesser Arapil, Cole’s left flank and rear were threatened by three French regiments. Moreover, the 7th Caçadores, which Cole had detached as a covering force, were swept aside by the numerically superior French who now turned on the 4th Division.

The 4th Division was attacked by Clausel’s division from the front, and by three of Bonnet’s regiments in the left flank. These latter three regiments consisted of fresh troops who found the 4th Division too exhausted to withstand this new French onslaught. The Portuguese 23rd Line, part of Stubbs’s brigade, began the retreat on the left of the line, followed in turn by Ellis’s brigade and soon both brigades of the 4th Division were in full flight back into the valley at the foot of the Lesser Arapil.

A view of the Lesser Arapil from the northern slopes of the Greater Arapil. The 1st and 16th Portuguese Line marched up the slopes to attack the summit in order to cover the advance of Cole’s 4th Division which was moving from right to left from beyond the Lesser Arapil.

The repulse of the 4th Division and Pack’s brigade left a yawning gap in the centre of Wellington’s position, and despite the hammering the French had taken elsewhere on the battlefield, Clausel (now in command following successive wounds to Marmont and Bonnet) was presented with the opportunity to salvage something from the wreckage of the day’s fighting, perhaps even a French victory. It was certainly a critical point in the battle. Clausel decided to grasp the opportunity with both hands and go for victory, even though behind him Leith and Pakenham were driving everything before them. Having decided upon this bold course of action Clausel threw his division into the gap, supported by three of Bonnet’s regiments and by three regiments of Boyer’s dragoons.

The ground to the west of the Greater Arapil was soon covered with the dark, dusty masses of Frenchmen launched by Clausel to save the day. In front of them Cole’s division reeled backwards towards the Lesser Arapil, while Pack’s broken brigade streamed away behind them. Ellis’s brigade was pushed back, almost to the Lesser Arapil, while Stubbs’s brigade, alongside it, was forced to form a square in order to protect itself from French dragoons who nevertheless got in among some of them. In fact, some French cavalry swept round and got as far as the 6th Division, Wellington’s reserve line, which had been brought forward to support the 4th Division.

Clausel’s counterattack represented the last, desperate attempt to salvage something from the day’s fighting, if not victory itself. But, as so often in his career, Wellington demonstrated his unerring powers of foresight and at 5.30pm brought forward Clinton’s 6th Division, who were fresh and yet to be involved in any of the day’s fighting. Clausel’s division was attacked not only frontally by Clinton, but also by Spry’s Portuguese brigade which Marshal Beresford detached from the 5th Division and led diagonally against Clausel’s left flank. Beresford, in fact, was wounded during this attack which halted Clausel’s division.

The steep slopes where Ferey formed his men to cover the retreat of the beaten French army. One can see just how easy it was for the rear ranks of Ferey’s men to fire over the heads of those in front. Ferey held out for some time here against Clinton’s 6th Division before the arrival of the 5th Division drove him off. Ferey, in fact, was killed here by a round shot.

Clinton’s 6th Division, meanwhile, continued its advance, with Hinde’s brigade on the right and Hulse’s on the left, and Rezonde’s Portuguese in the second line, their long lines overlapping both ends of Clausel’s division. Bonnet’s three regiments soon found themselves engaged against a superior firing line and were thrown back upon the main body of Clausel’s division, having suffered casualties of around 500 men each. Bonnet’s reverse exposed the right flank of Clausel’s division and forced it to retreat too. Seizing his opportunity, Wellington directed the 1st Division, still as yet inactive save for the light companies of the Guards, to drive a wedge between Foy and the Greater Arapil, a move which if successful would cut off Foy from the main body of the French army. In the event, Gen. Campbell, commanding the 1st Division, pushed forward only his skirmishers of the King’s German Legion, who hardly constituted a real threat to a veteran like Foy. Their advance was, nevertheless, enough to convince the three battalions of the French 120th Regiment, still occupying the summit of the Greater Arapil, that retreat was the better part of valour and they scrambled down the sides of the hill to rejoin the great body of fugitives now streaming away to the south-east, their flank coming under fire from Campbell’s Germans as they did so.

With Clausel’s courageous counterattack a failure, the battle of Salamanca entered its closing stages. Foy’s division was moving slowly but cautiously round the back of the Greater Arapil, threatened all the time by the 1st and Light Divisions; Sarrut’s division was heavily engaged trying to stem the relentless advance of the 3rd and 5th Divisions, while Ferey’s division clung to the top of a ridge to the south-east of the Greater Arapil. Ferey, in fact, constituted the last line of French resistance as the rest of the French army fell back towards him. Beyond the dark masses of fleeing Frenchmen could be seen clouds of dust through which burst Wellington’s triumphant divisions. Away to the west the 3rd and 5th Division drove forward with Bradford’s Portuguese and the 7th Division on their left. Squadrons of British and Portuguese cavalry hovered, gathering up surrendering enemy infantrymen and sabring any that resisted. Beyond the Greater Arapil the 1st and Light Divisions advanced, but the main and more immediate threat to the French came from Clinton’s advancing 6th Division.

French prisoners being marched back across the Roman bridge over the River Tormes into Salamanca, following the battle on 22 July 1812. After Clark and Dubourg.

Ferey had been forewarned by Clausel that his division was expected to cover the retreat and the acting commander-in-chief was not to be let down. Ferey was aided considerably by a fairly steep ridge which allowed those at the rear to fire over the heads of those in front, and so more firepower could be brought against the oncoming 6th Division of Wellington’s army. Ferey formed seven of his battalions into line with a single square on each flank and when Clinton’s men got to within 200 yards of the French position Ferey gave the order to open fire. Scores of dusty red-coated British infantrymen fell as the weight of fire from seven battalions of enemy infantry crashed into them. Clinton’s men halted to load and fire and the two sides began a deadly duel of musketry, comparable to that at Albuera, both sides trading volleys for the best part of an hour.

As the light began to fade, the spectacle was made all the more dramatic as the scene was illuminated by scrub fires kindled by burning cartridge papers. The scene itself resembled that at Albuera, and so too did the outcome, for it was the French who eventually broke, the power of Wellington’s infantry once again winning the day, but at a price. Indeed, as Ferey’s infantry fell back, it was left to the Portuguese to complete the job, the men of the 6th Division having suffered severe casualties. British artillery also joined in to keep Ferey’s men on the move and it was a round shot from one of these guns which cut Ferey in two, a sad end for a brave soldier who had inflicted heavy casualties on Clinton’s division. Indeed, even with Ferey gone his men continued to put up a gallant fight. They successfully drove back Rezende’s Portuguese brigade and it was not until the advancing 5th Division came upon the scene that the final blow was dealt by Wellington’s men.

Leith’s troops fell upon the left flank of the French, sending the French 70th Regiment into a state of sheer panic. The French army had been making a fighting retreat until that moment, but when the 70th broke and fled, panic spread throughout their ranks and soon almost the whole of the French army was in full flight heading towards the great forest which lay to the south-east of the battlefield. Only the French 31st Light stuck to their task, fighting as they went while chaos reigned all around them. Foy’s division fell back in an orderly manner too, shadowed closely by the 1st and Light Divisions, until it too reached the safety of the forest.

The battle of Salamanca ended with Wellington’s divisions too exhausted to pursue the French into the dense forest, through which thousands of panic-stricken French troops were fleeing for their lives. There was little point in Wellington sending in what troops he did have available, particularly as he believed that a Spanish force under Carlos d’Espana was holding the only real accessible river crossing over the Tormes at Alba de Tormes. The Spaniards had been left in Alba by Wellington when he had marched north from Salamanca, earlier in the campaign. D’Espana, however, had let his nerves get the better of him, had panicked and had withdrawn his force. Even worse was the fact that he had neglected to inform Wellington of this unauthorised move, rightly fearing the wrath of his commander. Therefore, instead of finding that the remains of the shattered French army were hemmed in against the left bank of the Tormes, an exasperated and furious Wellington discovered that they had simply marched across the bridge and through the fords to make good their escape. Wellington had ordered his divisions north towards Huerta, where the men sank down after the day’s exertions.

The battle of Salamanca had been a comparatively short one, but was a most decisive and, for the French, a costly one. Wellington’s army suffered some 5,214 casualties, including nearly 700 dead. French casualties are difficult to ascertain, but the historian Sir Charles Oman calculated the number at being around 14,000, including Marmont, Clausel and Bonnet, all of whom had commanded the French army during the day. In addition, 20 guns were taken as well as six colours, which sat rather nicely that evening alongside the two captured eagles.