CHAPTER TWO

The Second-Floor Flat Over P. J.'s

IN OCTOBER 2011, AFTER VISITING THE MAIN SALOON, I ENTERED a second side door on 55th Street, labeled sidecar, and huffed and puffed up the steep set of wooden stairs. Emerging at the top of the second floor, I found myself in a large, elegant room filled with square tables covered with crisp, white cloths sitting on a shiny, wooden floor. Along the exposed brick wall, comfortable, padded benches lined the entire length of the room. The walls were hung with fine pieces of art, and the many windows looked out on New York City streets. Frank Sinatra's voice filled the room. I was in the new restaurant named Sidecar built by Clarke's Group, the owner of P. J. Clarke's since 2001.

I had not been on this level of the building since the l940s when I visited my granduncle's fat. My fascination with Clarke's bar originated with the idea that my father and his brothers had grown up over this saloon in its solid-looking, red brick, Victorian-era building. In fact, between the years 1916 and 1924, four of the Clarke sons were born there. As I sat at my table waiting to begin the interview with the Irish American organization, I looked toward the front of Sidecar facing 3rd Avenue and remembered tales of my relatives' lives there.

An Irish woman, Annie Moore, was the first immigrant to pass through Ellis Island when it opened in the l890s; Irish immigrants made New York City the largest Irish city in the world. The census of l900 revealed that there were 692,000 Irish immigrants living among the three million people of the city. When this number was added to the third- and fourth-generation immigrants of the 1840s famine years, the Irish made up the majority group. This continued for another thirty years until the Irish majority evaporated due to the arrival of people of other ethnicities: Jews, Poles, and Italians.

One day in l904, two years after Uncle Paddy began working at Jennings's saloon, my grandfather, James Clarke, arrived at 3rd Avenue, tired and worn out from his voyage from Ireland. Uncle Paddy greeted him. “James, brother, céad mílle fáilte (a hundred thousand welcomes). Come and sit down, and I'll bring you food and a beer.” My grandfather never had such a welcome meal.

In the midst of this large migration to America by people from all over the world, Paddy and James had departed from their small

Grandfather James Clarke – l911

cottage in Cloonlaughil, County Leitrim, leaving their parents and seven siblings behind. Eventually four other siblings joined them in New York City: Michael, Rose, Annie, and Bessie.

Uncle Paddy told my grandfather that during his first years in New York he had seen remnants of Thomas Nast's cartoons picturing the Irish with apelike qualities, and he had heard about the Know-Nothing political party, strong opponent of Irish immigration. This Anglo-Saxon enmity had its roots in England, where stereotypes of the Irish suited a government that had brutalized the Irish and abolished their language, religion, and land rights.

But, at the same time, Uncle Paddy said that he was encouraged that the Irish were starting to become more accepted in America and that there was less fear of their causing crime or bringing the Pope over to rule. The Irish were creating their own neighborhoods and a network of parishes, unions, and political precincts. Saloons were an important part of the network, as they were the Irish workingman's club. In addition to having these networks, both Clarke brothers had two advantages over other ethnic immigrants: They spoke English, and they were acquainted with the dominant Anglo-Saxon culture of America because of the 800-year English colonization of Ireland.

Even so, there was still antagonism toward the Irish. My grandmother, Mary Mahon Clarke, who also arrived in l904, told my father about signs in the windows that read: NO IRISH NEED APPLY, referred to as “NINAs.” Sometimes the signs read: only protestants need apply. It seems that the Protestant householders feared that Irish-Catholic girls, serving as maids, nannies, and cooks, might report their behavior back to their priests or secretly baptize their children. While most people accept this discrimination as a fact of history, some historians take the view that NINAs were an overblown myth. Wherever the truth may lie, prejudice, perceived, or otherwise, promoted solidarity among the Irish.

Once Uncle Paddy owned his own business, this prejudice surely influenced him to hire newly arriving Irishmen as his bartenders and waiters and to support the Democratic Party and the trade-union movement. Like other Irishmen, he bonded with his kinsmen and continued to send funds home to his family across the Atlantic. He was even able to take an ocean voyage and visit them in l909. By belonging to various Irish networks, Paddy Clarke found a way to replace what he and his brother James had left behind in their rural village—a stable social life where everyone had a role to play under the watchful eyes of parents and priests.

However, many Americans continued to believe that most Irish were violent drunks or criminals like Big Tim Sullivan, the political boss of the East Side of Manhattan, or Owen Madden, who was a highly successful city bootlegger during the l920s. Uncle Paddy, as a saloonkeeper, met with special opprobrium—his business was viewed critically, especially outside of New York. Many Americans knew that large Irish gangs had been associated with saloon life. It did not help the Irish that they continued to celebrate their love of alcohol in song and story—drinking together was a cultural trait of which they were proud, but it did not earn them respect. It is regrettable that at this time few Americans knew of Irish literary and educational accomplishments.

Class distinctions also caused prejudice toward the Irish who arrived from their desperately poor villages without funds—Uncle Paddy came with $5 in his pocket. The Clarkes were poor, but they were literate, unlike many of the 1840s famine-era Irish emigrants. After several years in America, Uncle Paddy joined the Irish who were moving into the middle class. In fact, economics had been a primary motivation for his purchase of the bar, giving him a sense of security and enabling him to be his own boss. There were others, like Judge Daniel Cohalan, Irish American millionaire and militant advocate of Irish independence, who had become wealthy, but were still not accepted by many Americans.

Unlike Uncle Paddy, my grandfather lacked the funds to own a business in New York. After a brief stint working with Paddy at the bar, James Clarke sought a labor job—he had known hard work in Ireland, and he did not avoid it in America. When Grandpa grew tired of bartending, Paddy sent him to the local Democratic Party hall run by Tammany, the group that controlled much of the

Grandpa James Clarke with his three eldest sons John, Joe, and Jim outside Clarke's bar – 1917

politics and economy of New York City and often used the saloons to recruit voters.

One Sunday afternoon my grandfather sat next to me, smoking his pipe and recalling that event.

“I sat on a hard bench in the hallway waiting to be called. Moving inside to an office, the conversation with the ward boss was easygoing; at first he asked how my brother Paddy was. Then he followed with questions about where I had lived in Ireland, how conditions were back home, and if I liked New York. Finally, the boss got down to business, the business of finding me a job. This turned out to be an apprenticeship as a steamfitter in exchange for my support at the ballot box, voting for the Democrats.”

Some say Tammany Hall's knack for organizing came from the example of Irishman Daniel O'Connell, who had succeeded in regaining rights for Catholics in Ireland taken from them by the English—property rights, voting rights, and access to education and jobs. O'Connell did this by a long nonviolent campaign that involved membership drives and mass rallies and culminated in the 1829 Catholic Emancipation Act. Tammany Hall might have emulated O'Connell's method, but it was with a touch of corruption and cronyism. Nevertheless, many immigrants like my grandfather were able to overcome their impoverished circumstances in America because of the Hall's provision of housing and jobs, much of which was arranged at the local saloon.

Despite Grandpa James's long working hours, he managed to go to the hall dances sponsored by each Irish county society—Uncle Paddy never did make time to do this, and this may be one of the reasons he remained a bachelor. These societies provided a circle of friends who came from the same part of Ireland and helped keep the Irish informed and united. The Irish made their presence known in their new cities through membership in these societies.

One Saturday night on the East Side of Manhattan, Grandpa met a young woman, also from County Leitrim. Mary Mahon had a soft voice, and Grandpa always remembered her first words to him: “Sure, and I'll be happy to dance with you.”

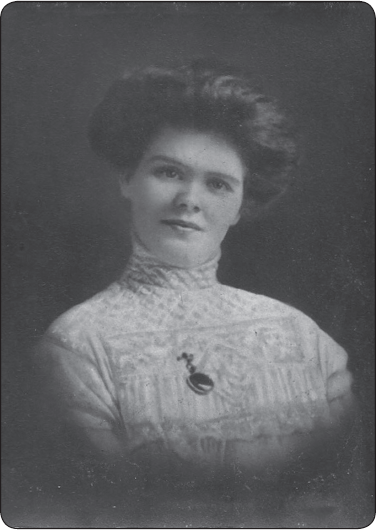

Irish immigrants liked to marry people from their home county, but my grandfather said that he did not care where Mary Mahon came from. Grandpa was smitten after the first dance. From her pictures I know that my grandmother was a beauty with an ivory complexion and gorgeous auburn hair, piled high on her head. She had the smile of an angel and captured my grandfather's heart for his lifetime.

When my grandmother Mary and her sister Alice arrived in New York City, they were assisted by the Sisters of the Mission of Our Lady of the Rosary for the Protection of Irish Immigrant Girls. This organization reportedly helped 12,000 women obtain domestic work. Mary and Alice were, like a great number of the Irish single women—perhaps 60 percent of them—employed as

Grandmother Mary Mahon Clarke – l911

household servants in Manhattan and on Long Island. It was difficult work, and they were poorly paid, but household employment was safer and offered better benefits than the factories did because women could live on the premises and receive regular meals with their wages. These two Irish girls, who had come from impoverished backgrounds and now worked in mansions, began to dress like ladies and appreciate fine linens and furnishings.

Grandpa James had many a dance with Mary Mahon. Established as a steamfitter, installing heating systems, my grandfather was able to propose marriage to Mary, and the couple exchanged their vows on November 2, l911. In their wedding picture, a smiling Mary is standing, and a serious James is seated in a chair at her side in the traditional pose. James was thirty-two, and Mary was twenty-eight. Uncle Paddy served a meal at his saloon after the wedding ceremony.

Both my grandparents had saved some money, and Mary ended her work as a housekeeper on 5th Avenue when she became pregnant with my father, John, in l9l2. As in other families, money was tight in the Clarke family, but my grandmother did not need outside employment after the children were born, unlike 50 percent of working-class married women in New York City did at the time. While the James Clarkes were not poverty-stricken, they could not have afforded the higher rent of a single-family home.

At first my grandparents lived in an East Side rooming house, but as the family grew, they were invited by Uncle Paddy to share a fat with him in the tenement building housing the saloon on 55th Street. That building dated back to 1868, according to city records, which makes it one of the oldest still in use in New York City. In l916 my grandparents moved into the second-floor fat over the saloon with my father, age four, and my Uncle Jim, age two. In that four- bedroom, cold-water fat above the bar, Dr. Cooley, a mixed-race physician, was called to deliver four more sons to my grandparents—Joseph in l9l6, Thomas in l9l8, Charles in l921, and Raymond in l924.

The word tenement simply meant that someone owned the building and rented it out to as many tenants as would ft. The Tenement House Report of l900 states that two-thirds of New Yorkers lived in tenement buildings. Since l898, New York City had included Manhattan, Queens, the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Staten Island, but half of all tenement buildings were in Manhattan. Most tenements were five and six stories high with numerous families, but the one on 55th Street and 3rd Avenue had four stories and sixteen fats—four to a floor.

Families usually paid about $14 for a four-room fat, and this provided a high return to the owner—in some cases as much as 30 percent. As with all other tenements, where the first floor was dedicated to commercial use, Paddy Clarke's saloon occupied the ground floor, with its dark wooden entrance doors facing 3rd Avenue.

Before he died, Uncle Joe Clarke sent me a letter describing his memory of life over Clarke's bar. He said that their home was a cold-water fat, meaning that all water had to be heated on the stove. The building itself was typical of its time, with no steam heat, just a coal stove in the kitchen, and therefore chilly in the winter. Picture the family huddling by the coal stove or using soapstones in their beds for warmth. Because Grandpa James was a steamfitter, he was eventually able to put a radiator in the dining area of their fat and, later, add an electric heater in the front room.

There was no bathroom, just a toilet in the hall of each floor; however, in the slums of the Lower East Side, there were only outhouses. Uncle Joe wrote, “We boys took baths in the kitchen wash-tubs and dried ourselves alongside the coal stove until we were old enough to go down to the public baths on 54th Street between 1st and 2nd Avenues.”

Grandma Mary did her wash in tubs in the kitchen, using a bar of Kirkman's soap and a washboard. As was typical, wash was hung on an outside line stretching between the tenement buildings, revealing the cleanliness of the inhabitants. Lights in the rooms and the hallway were fueled by gas, but later on electricity came to the fats. There was no refrigeration until l930, so Grandma Clarke shopped every day and sometimes left food out on the fire escape in the cooler seasons.

Uncle Joe wrote that “one of the worst features of our fat was its location by the 3rd Avenue Elevated tracks that masked conversations as the trains roared by. The whole fat vibrated and the floor shook.” Even today I myself remember what that train noise was like. There was no chance for any conversation to take place. Uncle Joe said that due to the noise from the trains, as well as from the saloon, my grandmother took her sons on many walks around the city. She especially loved walking up and down Park Avenue and then over to 5th Avenue, where she had first worked as a servant girl after coming to America.

Walking was one of the working-class New Yorker's favorite pastimes, along with going to Central Park and taking an occasional trip to the Coney Island amusement park. Recreation was simple. People enjoyed being out on the street, especially during the hot summers when they spent their nights sleeping on the roofs or fire escapes. The tenement buildings were hot due to the lack of adequate ventilation, and because their fat, uninsulated black-tar roofs captured the heat.

Despite their tight quarters, the Clarke boys had a good time in their building. Once my dad related a story to me about his playing on the fire escapes that were on the side and front of the saloon. He and his brother Jim liked to tip glasses of water over

The Clarke boys with their uncle's new car

the dirty fire escapes outside their bedroom window, and one day the water fell onto a policeman's cap. Dad and Uncle Jim heard the policeman shout as he ran inside up the stairs—terrified, with their hearts beating, the boys climbed off the fire escape back through the window and ran to hide under their bed. Moments later, they could hear the policeman's angry voice at the door, their mother Mary assuring him that she would scold her sons. But my dad told me that when the policeman finally left, she merely rolled her eyes at them, seeing the funny side of their caper.

A while later the same police officer, Tom Quilty, began playing stickball with the Clarke boys and their friends on 55th Street, a form of community policing. Some of the boys who went to school with my father and his brothers wound up in prison, but the Clarkes had great guidance from their solicitous parents, their neighbors, and the Sisters of Charity at St. John the Evangelist Catholic School, escaping the delinquent life. My dad and his brothers had the ben-eft of a wonderful teacher at St John's school—Helen Bentley, who remained a lifelong friend. A single woman, Miss Bentley arranged frequent parties for the children out of her own funds.

In addition to the austerity of tenement life, another problem was disease. The Tenement House Commission of l900 reported that tuberculosis (TB) was common due to overcrowding. In l935, when the fourth son, Tom Clarke, was seventeen, he contracted TB and lost one lung, but he recuperated at Saranac Lake in upstate New York. Despite the fact that Uncle Tom lived in a very clean fat and that New York City had improved its health codes, he still contracted TB. Tom's experience of incapacitation and recuperation led him to an epiphany—and he entered the Jesuit seminary after his graduation from Xavier High School.

While life over P. J.'s was difficult by today's standards, it was far better than the worst of conditions in New York at that time. There were tenements in Manhattan where conditions were much more severe, especially in the poverty-stricken neighborhoods of the Lower East Side where 500,000 people lived in 1900. This part of Manhattan, with its teeming immigrant population, mainly from eastern and southern Europe, also held many factories, docks, slaughterhouses, and power stations, causing increased air pollution, high noise levels, and obnoxious smells. Mice, rats, and roaches, roaming among the garbage-filled streets, were another danger, and, despite the invention of the electric rail, horses were still kept in these neighborhoods.

These fats were poorly lit, inadequately ventilated, and overcrowded. They were often fire traps. Forty-seven percent of fires in New York City took place in tenements—there were no fire stairways, just fire escapes whose ladders proved difficult for children and older people. Many tenement dwellers were subjected to criminal types, dirty, unsanitary conditions, and loud noise far into the night—dens of violence and misery.

It is clear that the Clarke's tenement at 55th Street and 3rd Avenue was in the better category of buildings—less of a fire trap because it was smaller, not as crowded, with little crime. Uncle Paddy was trying his best to have the fats over his saloon be as comfortable and safe as possible. That is why he had invited his brother James to bring his family to 55th Street and later his sister Annie and her husband, John Grimes, who emigrated shortly after James did. The families in the tenement knew each other and were locals like Pappi, who ran the shoeshine stand, and the Duane family, friends of the Clarkes. It was a very close community. Nevertheless, when Uncle Paddy had enough money to buy the tenement building from the owner, he did not seize the opportunity, declaring, “I can't understand why anyone would want to own a tenement.”

But it was the unhealthy tenements that caught the attention of the turn-of-the-century progressive reformers who lumped the whole category of tenements together. These reformers were often members of temperance and religious groups who developed a view that if alcohol were prohibited, life in these tenements would improve. From l901 on, these progressives did get some improvements made, such as better sanitation due to the newly formed street cleaners who wore white uniforms and were called “white wings.” The street cleaners' labor did help reduce disease, as did the fact that water supplies were being tested to guard against water-borne infections.

Helen Hines and John Clarke, Helen Marie's parents, with their classmates on Confirmation Day l924 at St. John the Evangelist Church

Calls for reform in city conditions where the poor lived came from many quarters.

The wealthy folks were embarrassed by tenement housing and thought it would prove negative to investors. They also feared a popular rebellion. Employers felt conditions in the worst tenements would prevent workers from being efficient. Progressive reformers were concerned that the children of these families might become criminals. City officials wanted the burgeoning metropolis to look prosperous for tourists.

Like the tourists, the Clarkes found New York City an exciting place to live—it was now the largest city after London and was becoming a very important financial hub, as well as a manufacturing center. The spectacular skyline of Manhattan was emerging due to the construction boom beginning in 1900 and lasting for the next thirty years. Prominent in the skyline was the Wool-worth Building, with its fifty-five stories, making it the tallest building in the world in l913. The city planners were tying this large metropolis together—suspension bridges and the new IRT subway system joined the elevated lines, such as the one that ran past Uncle Paddy's bar.

Technology was changing people's lives. The electric streetcar was replacing the horse-drawn carriage, and in l903, with the invention of the internal combustion machine, the wealthy began driving Packard automobiles through the city's streets. In l908, Henry Ford produced the Model T, a much more affordable vehicle, and the Clarke boys began getting rides from their Aunt Rose Clarke Dixon's husband, Jack. Other inventions appeared—the vacuum cleaner in l901, the washing machine in l907, the electric toaster in l909—but it is certain that Grandma Mary did not have any of them in her fat.

The James Clarkes had moved over the saloon during the very year, l916, of the Easter Monday uprising in Dublin. In November 1927, five years after Irish independence was won, tragedy struck when the six Clarke sons lost their mother to a case of ruptured appendix that turned into peritonitis and then pneumonia. Mary Mahon Clarke was forty-four. My grandmother was not alone, as thousands died of pneumonia and tuberculosis every year, despite New York's attempts to improve health with bacteriological labs, public baths, water chlorination, and pasteurization of milk.

Uncle Joe Clarke wrote that his mother was ever kind and generous and frequently made many of Uncle Paddy's meals and tidied up his room. He said that despite all the stress of living over a saloon next to the 3rd Avenue Elevated train, his mother was a happy person, full of smiles and good humor. One day when Uncle Joe saw her crying—an unusual occurrence—she told him that she was missing her own mother over in Ireland.

When Mary died, my grandfather James was totally bereft and had to be pulled away from her death bed. For years I could only imagine how sorrowful the scene was in the fat over Clarke's bar: six young boys suddenly without a mother and a very distraught husband in shock. Uncle Joe, who was eleven years old at the time of his mother's death, gave me a clearer picture of that day. At the age of sixty, Uncle Joe wrote the following: “I recall the night she died, when Dad came back with the others from the hospital, and (I), hearing the crying of Dad, knew that something was wrong. For months he would cry himself to sleep on a couch in our living/ dining room.”

As was traditional, my grandmother was waked in her home over the bar, wearing a pair of white rosary beads around her neck. Because she was beloved, many people from the neighborhood came to pay their respects. Grandmother Clarke's funeral mass was held at St. John the Evangelist Church, and her casket was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Queens. I treasure a set of her postcard messages kept by my grandfather until he died.

I never remember any conversations with my father about how he felt after the death of his mother. My dad did tell us, with a catch in his voice, about how sweet his mother was, and he spoke fondly of Aunt Rose Clarke Dixon, who helped take care of the six boys in their fat over the saloon. With the death of his wife, my grandfather became a single parent, and because he was a melancholy man, this took a toll on the Clarke sons, who were more used to their gentle mother.

At the time of her passing, my father, John, was fifteen, and the youngest of the six, Ray, was only three years old. Their mother's death left a hole that no one could ever fill. That was certainly true for my grandfather, who did not remarry and instead mourned his “Molly” until the day he died at the age of ninety-six. As Senator Patrick Moynihan of New York would one day say after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, “What's the use of being Irish, if you don't know the world is going to break your heart?”

While there were many occasions when my grandfather spoke of missing Mary, the great love of his life, he never regretted coming to New York. His sons were raised as Americans. Grandfather James would never answer questions about Ireland—all he said was his homeland was a hard place because of English rule. In those moments we watched his face become distorted and angry. Glad to be in America, my grandfather was like many other Irish immigrants, though some of those other immigrants never got over their homesickness. Grandpa was never actively involved in any New York groups that sent money and weapons to the Irish cause, too busy with his long hours of work and raising his six sons over a bar in the middle of Manhattan.