CHAPTER FOUR

New Beer Day

THE PROHIBITION PERIOD WAS NOT AN EASY TIME FOR PADDY Clarke, even though the odds of a small saloon being shut down were not as high as many of his peers had feared. The federal enforcement bureau was understaffed with poorly paid agents, and they tended to raid the more famous midtown speakeasies so that they could get publicity in the newspapers for their arrests. Uncle Paddy also knew that when the federal agents made arrests in New York, they were hampered by new practices: widespread plea bargaining and reduced sentences from New York City judges whose courts were overloaded with cases.

The NYPD officers often turned a blind eye to saloonkeepers like Paddy, but some did seek a bribe. Local police were required to enforce prohibition laws, but in l923 Uncle Paddy was elated when the Mullen-Gage Act was repealed by the New York State legislature due to the encouragement of Democratic Governor Al Smith. Thereafter the NYPD was exempt from its enforcement role and could return to arresting more serious criminals. Uncle Paddy felt any possible harassment from the NYPD should end.

Despite this change, there were some New York City saloon owners, who, trying to stay open, were still shut down by federal agents. The upper brass of the NYPD, largely Irish, were often connected with Tammany Hall politicians who opposed Prohibition and had ties to the federal agents. Uncle Paddy was never arrested, nor was his bar shut down. He may have known important people in high places.

However, my granduncle did not enjoy acting surreptitiously. Like other neighborhood saloon owners, he wanted to run his business openly. He was often anxious and hoped Prohibition would be a “bad cold that would go away.” One day he pulled my sixteen-year-old father aside as Dad was polishing the brasses in the bar. Uncle Paddy let it slip that he was betting on Governor Al Smith of New York to win the presidency.

Al Smith himself had flaunted the prohibition law and served liquor in the Governor's Mansion. Meanwhile, the Democratic Smith was not alone—it was widely known that Republican President Warren G. Harding served liquor at his weekly poker games in the White House. But because of Al Smith's attitude, the “drys”

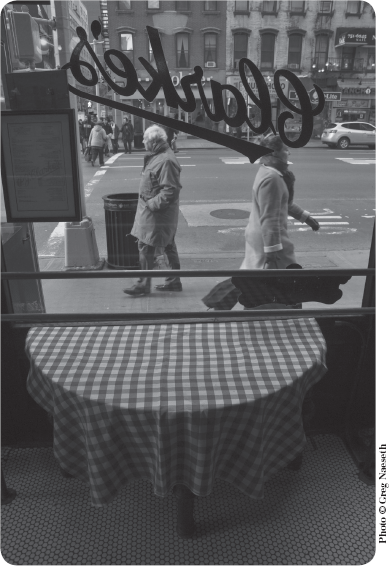

This way to the dining room – 2012

began to refer to New York City as “Satan's Seat” and acknowledged that they had to be successful in the nation's largest drinking city or their movement would not be viable. The “drys” called for stricter enforcement.

Following Smith's example, when the 1924 Democratic presidential nominating convention was held in New York City, alcohol appeared readily available for the visitors, while “wets” and “drys” argued inside the convention hall. Four years later, in l928, Al Smith was nominated as the Democrats' presidential candidate, and he authorized a platform that included ending Prohibition. His Republican opponent, Herbert Hoover, did not favor overturning the Eighteenth Amendment, but he called for some modification in the Volstead Act that had implemented the amendment.

Candidate Al Smith acknowledged reality; he knew that by l927 there were twice as many speakeasies in New York City as there had been saloons before Prohibition—32,000 illegal drinking spots. Indeed, there were 200,000 such places across the nation. Researchers indicate that in the first years of Prohibition, alcohol consumption fell by perhaps 50 percent and deaths from cirrhosis of the liver by 30 percent. But sales of medicinal alcohol (95 percent pure) increased 400 percent between l923 and l931. Many Americans began moving from beer and wine to hard liquor because it was actually cheaper to obtain scotch whiskey from Canada than to get beer from illegal American breweries. The high

Inside looking out on an autumn day in Manhattan – 2012

cost of bootlegged liquor was a factor in the decline of drinking during this period, but after the Roaring Twenties got underway, bootleggers, traffickers, and speakeasies grew in numbers, and drinking came back.

The law was being undermined. Hoagy Carmichael was quoted as saying, “The 1920s came in with a bang of bad booze, flappers and bare legs, jangled morals, and wild weekends.” He should have added jazz to his list. Some researchers claim that more people were drinking hard liquor in New York than they did before Prohibition.

One day Paddy Clarke picked up his newspaper and read what New York City's Republican reform mayor, Fiorello LaGuardia, had said: “It is impossible to tell whether Prohibition is a good or bad thing, since it has never been enforced.” LaGuardia added that to enforce the law would require 250,000 police plus 250,000 more police to supervise the first group. A progressive reformer and opponent of corruption and hypocrisy, LaGuardia announced his desire to see Prohibition ended.

In l928, Uncle Paddy voted for Governor Al Smith because he was a Democrat and because he promised to repeal Prohibition. There were some Irish, mainly outside the big cities, who distrusted Smith because he was too “uppity,” so they voted Republican. Uncle Paddy knew that Smith's candidacy was a long shot—the country was still feeling prosperous and giddy over the Roaring Twenties and many people credited the Republican administrations of Presidents Warren G. Harding and Calvin Coolidge for this “normalcy and prosperity.” And when the resurrected Ku Klux Klan added Catholics to their list of enemies and began an ugly attack on Smith's religion, Uncle Paddy became very pessimistic.

In November l928, Paddy Clarke's morning newspaper an -nounced that the Republican Herbert Hoover had won the presidency by an overwhelming margin. Behind the scenes, pundits wrote that Smith lost because he was a “wet” Catholic and had been attacked not only by the Klan but by an alliance between the “drys” and fundamentalist Protestants. My granduncle chuckled when he read what Al Smith said after the returns were in: “The time hasn't come when a man can say his beads in the White House.” Smith, despondent over his big loss in the election, exited politics.

After the 1928 presidential election, the Anti-Saloon League made a big mistake—imagining that Al Smith's huge defeat was due to his opposition to Prohibition, they pushed for a stringent criminal law called the Jones Act. This federal legislation turned Eighteenth Amendment violations from misdemeanors to felonies. Conceivably, a bartender could be sentenced to five years in prison for a first offense. One notorious case of a Michigan woman, sentenced to life in prison after her fourth violation of selling alcohol, made national headlines.

Uncle Paddy sensed that the “drys” had gone too far and that their refusal to compromise would encourage many more people to call for a repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment. He was relieved to read that newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst called the Jones Act “a menacing piece of repressive legislation,” and he was very pleased when the Irish World newspaper finally conducted a campaign actively opposing the prohibition laws as a loss of freedom.

A year after Herbert Hoover was elected president, the country faced another crisis. Uncle Paddy, like most investors, lost a great deal of money when the stock market plummeted. New York City was hit hard in l929. Fortunately, Paddy Clarke was thrifty and his bar had gained new customers, so there was never a threat of bankruptcy. For one thing, some of New York's more famous restaurants, such as Delmonico's, had been shut down due to Prohibition and, as a result, neighborhood saloons like Paddy's gained customers. Uncle Paddy continued to stay in business through the economic downturn despite the fact that multitudes of New Yorkers were out of work—the Wall Street crash had hit all sectors of society. Perhaps that drove people into the speakeasies in greater numbers.

Paddy Clarke began to notice that more middle-class customers were frequenting his bar, and these New Yorkers told him that they resented Prohibition as a loss of freedom. They became an important group advocating for its abolition. The elite had flaunted their consumption of illegal alcohol from the very beginning,

A well-stocked bar at modern day P. J. Clarke's – 2012

stocking their clubs and homes with large amounts of liquor before the law went into effect and buying on the black market afterward. The working class resented Prohibition as a personal assault on their ethnic traditions and as a deep imposition on their lives. They expressed their anger to Paddy Clarke, annoyed that the elite appeared to be above the law.

When halfway into his term, President Hoover, a Quaker who hated alcohol, authorized the Wickersham Commission to look into the effects of the Eighteenth Amendment, Uncle Paddy felt there was a chance of repeal. In l930 this Commission pointed to the corruption and dereliction of duty among the federal revenue agents and also to the success of organized crime elements in replacing businessmen bootleggers and undercutting the law. Paddy Clarke was cautiously optimistic when President Hoover announced that the states, not the federal government, should decide whether they would maintain Prohibition, which the president referred to as a “noble experiment.” Uncle Paddy hoped that New York might act, but Hoover failed to move the process along.

Despite Hoover's lack of leadership, the movement to end Prohibition gained weight for several reasons. As Paddy Clarke could attest, people liked to drink, and in New York City, the fact that alcohol was illegal somehow made it more sophisticated. The “drys” had counted on New York closing down its drinking establishments, but the “City on a Still” had only created more of them. At the passage of Prohibition, Paddy Clarke had decided that its laws were largely unenforceable and that his laboring-class customers would never support it. He was right.

Uncle Paddy heard that in the small towns of America, the use of a medicine made from Jamaican ginger extract, known as Jake, was being widely used. Jake was 85 percent alcohol and was legal, but because it was often contaminated with chemicals to stretch out the quantity of the solution, the result was a poisonous “Jake leg.” In the cities, bootleggers were stealing industrial alcohol, and, overreacting, the government ordered poisons to be added, killing 1,000 people in New York alone. The resulting deaths in cities and small towns helped produce a backlash against Prohibition.

Businessmen joined in, claiming that Prohibition had inhibited their trade—people seemed to go out less, and the entertainment industry protested. A plus for Uncle Paddy and the movement to overturn Prohibition was the fact that movies were popular, and drinking by actors and actresses on the silver screen helped make alcohol more acceptable again.

But Paddy Clarke was growing impatient. He could not understand how the American people could keep such an unpopular and unsuccessful law on the books. When it became clear that the murder rate had doubled due to alcohol wars between organized crime syndicates, Uncle Paddy asked his fellow saloonkeepers when Americans would understand that Prohibition was devastating and that evil men were benefiting economically.

Then Uncle Paddy got some help from a surprise quarter. Many mothers who had supported Prohibition watched their teenage daughters and sons criminalized as they rode around in automobiles, drinking from flasks; these women began calling for the law to be overturned. A leading New York City socialite and Republican spokeswoman, Pauline Morton Sabin, campaigned very effectively for the end of what she considered the corrupting and ineffectual prohibition laws by bringing people from all political persuasions and classes into her fold. Historians hold her up as one of the principal leaders in the fight to end Prohibition. Women had been one of the largest forces in the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, and, after they got the vote with the Nineteenth Amendment, they became active politically, as well as socially, flocking in large numbers to the new speakeasies for cocktails and cigarettes. Now they would lead the repeal of Prohibition.

As the economic depression deepened, the hard times became the final catalyst that led to the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment, just as World War I had been the event that encouraged the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment. In those difficult economic times, many businessmen favored legalizing and taxing alcohol, possibly decreasing their own tax liabilities, while government agencies also saw an opportunity for increased revenues if legalized alcohol were taxed. Paddy Clarke realized a tax on alcohol would affect him, but it was well worth it to have Prohibition ended.

Uncle Paddy cheered when Democratic presidential candidate Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced that he advocated the complete repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment. During his 1932 campaign Roosevelt claimed that the law was a failure and that the U.S. Treasury would gain hundreds of millions of dollars from legalizing and taxing beer alone. Roosevelt's opposition to Prohibition worked and, along with the horrific economic conditions in the nation, helped him win his overwhelming victory in l932; if this man stood against the government's legislating private morality, the people approved of him for the presidency.

After Roosevelt's election, Uncle Paddy was hopeful that the ban would be removed, and to his delight the president immediately signed an executive order restoring beer and wine to legal status. With the country deep in the Great Depression, FDR was reported to have said that “it was a good time for beer,” and the first case of post-Prohibition beer was delivered to the White House by a team of Clydesdale horses. In New York City, thousands gathered for “New Beer Day.” The federal government reported that on the first day when beer was legalized again it collected $10 million in taxes.

Soon, New Yorkers would have that beverage for breakfast to celebrate the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment. Uncle Paddy was surprised that Prohibition ended as quickly as it did when, in April l933, the Twenty-First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed and Section 1 read simply as follows: “The eighteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.” Michigan was the first state to ratify and Utah the thirty-sixth state, thus giving the necessary two-thirds approval. This action revised the role government would play in moral reform and offered a note of hope that perhaps the economic situation in American would improve.

On the day of the passage of the Twenty-First Amendment, Uncle Paddy smiled as new and old customers packed his place. When the Eighteenth Amendment was passed, Uncle Paddy had read the words of Secretary of Navy Josephus Daniels: “The saloon is as dead as slavery.” The country, in which the Puritans had built a drinking place before they built a church, proved Daniels wrong. Americans did not like their personal morality legislated; drinking had gone on during Prohibition, and now it would continue legally. Paddy Clarke's “bad cold” was cured.

Between the deliveries of whiskey that arrived on the shores of Long Island from Canada, Uncle Paddy's mixture of gin, and his supplies of the legal 1 percent “near beer,” Clarke's customers had made it through the Prohibition years. Uncle Paddy was a survivor; he had trafficked illegally in alcohol, but had escaped punishment. On the day Prohibition ended, pedestrians passing by Clarke's bar saw a sign posted: FAREWELL TO THE 18TH AMENDMENT.