CHAPTER FIVE

New York's Finest

WHILE CUSTOMERS HOBNOBBED AND DRANK DOWNSTAIRS, AN IRISH family had struggled through the day-to-day challenges of the times upstairs. The James Clarke family lived over Clarke's bar until 1937, when my grandfather, retired on disability from steamfitting, moved with four of his sons to a rental house in Woodside, Queens. My father, John, was married and living nearby, and my Uncle Tom was in a Jesuit seminary. When my grandfather heard where his sons had relocated him, he said, “Woodside, my God, you can't even get a beer out there!” Despite their move, the family continued to have strong ties with Uncle Paddy and his saloon.

The difficult Prohibition period had ended with Roosevelt's election, but the Great Depression was still crippling the nation. It was l935, in the midst of the Depression, when my father joined

Helen and John Clarke in the Easter Parade, New York – 1935

the NYPD. The next year he married his childhood sweetheart, my mother, Helen Hines, on October l7. Grandpa Clarke told him that he was too young at age twenty-four to get married, and Uncle Paddy concurred. The Irish married late. A very handsome couple, my parents were captured by a New York Daily News photographer as they were walking up 5th Avenue in the Easter Parade of l935. My mother looked like Greta Garbo's sister, and my father resembled Cary Grant. Uncle Paddy pinned up the picture behind the bar.

My mother always recalled that Uncle Paddy had offered Dad money to attend college, but he said he wanted to go to work— no more schooling for him. But obviously Uncle Paddy must have been very fond of my dad. A generous man himself, Dad took on the task of keeping Paddy's financial books after he moved out of the fat on 55th Street. Many Sunday afternoons when we visited the saloon Dad would leave us to go downstairs to do this work. While he was gone I would wander to the front bar, where the Irish bartenders treated me royally. Once I heard Dad tell my mother that he would not accept any money from Uncle Paddy for his time on the books.

There were times when my parents reminisced about Dad's first job out of high school, working in l930 as a draftsman in Stamford, Connecticut, hoping to study architecture. They wondered what might have happened if he had not given up drafting work in order to have the security of an NYPD payroll check. The term, “New York's Finest,” had its origin during the Great Depression because so many of the men who joined the NYPD at that time had good educations and fine credentials; the economic times were too difficult for them to utilize their trade, college, and law degrees.

My father had many different posts with the NYPD. He was a desk sergeant in Brooklyn, a fingerprint expert, a lieutenant in lower Manhattan, and a “shoofy,” an officer assigned to see if the patrolmen were on task. He hated this last duty. One of the effects of Dad's police career with its odd work schedule was his limited opportunity for social associations. This contributed to the fact that his brothers were always his chief friends.

Growing up, as the eldest son, Dad had assumed a great deal of responsibility for his younger, motherless brothers. This pattern continued through his adult life, and I was always struck by what a good big brother he was. For Dad, people were more important than money. His attitude did not happen by accident and shows the influence of his elders. Dad and his brothers, who lived over P. J.'s, were all “New York's Finest.”

In l942, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, there was a Christmas sendoff for Charlie Clarke at Clarke's bar as he departed for army maintenance school and eventually for action in the Pacific. From family conversations I can reconstruct this event. All the Clarkes were gathered around the front bar, and Grandpa Clarke looked very worried. His third son, Joe, was already posted as

John Clarke, new officer at the New York Police Department – 1936

an army instructor at a base in the States. A few months later, his youngest son, Ray, received his draft notice and had to give up attending Manhattan College. Ray was also headed for the Pacific Theater.

The night of the sendoff for Charlie, Uncle Paddy said, “James, you need to stay brave and be glad that all your sons are not going to war.” My dad's occupation as a police officer was protecting him from the draft. Uncle Tom was studying to become a Jesuit priest, and all religious men were exempt from fighting. As a New York City fireman, Uncle Jim did not have to serve in the armed forces, either. Jim had affiliated himself with the Catholic Worker House in lower Manhattan, started by the famous pacifist Dorothy Day. Under her influence, Jim declared himself a conscientious objector, but it was his freman's job that protected him from the draft.

Before he died, Uncle Joe sent me a packet of letters he had saved that were written to him by my father when Joe was in the army. These dozen letters penned between December l942 and April l943, when Dad was thirty years old and Joe was twenty-four, are an example of my father's brotherly concern, in this case for Joe's health as he advanced through army officer training school in New Jersey. Dad wrote: “Joe, we want to send you whatever you need—Helen and her mother have made a large care package for you.” Dad always ended his letters to Joe by saying how lucky the

Jim Clarke, at the New York City Fire Department ceremony, standing with John Clarke, Helen Marie's father – l935

people on the home front were. He lived his life with a good deal of gratitude, as did his brothers. Luckily, all three sons who went to war returned home safely.

In the middle of his life, Dad became especially close to Uncle Joe Clarke who was a charming man with excellent business acumen. He was selfless in his devotion to his family, his clients, and his employees, as well as to the extended community, serving on several charitable boards. Of all the Clarke sons, Joe appeared to have the deepest attachment to Irish culture and song, having absorbed it during his years over the saloon.

When Dad had narrowly missed the acceptable score on the civil service exam to become a police captain, he decided to retire from the NYPD at age forty-three. He eventually became employed at his brother Joe's firm, New York Roofing Company, as the supervisor of the roofing crews and later as an accountant for the company, a position he held until his death in l982. Dad always said that Uncle Joe was the best boss any man could have.

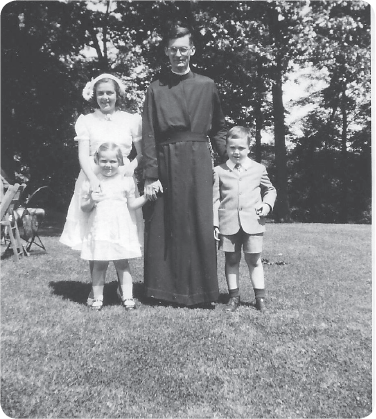

Dad also had a special relationship with his brother Jim, who was two years younger and my godfather. Uncle Jim remained a NYC fireman until he decided to enter the Capuchin Franciscan seminary and become a missionary priest to Japan. This was a surprise to many members of the family as Uncle Jim liked girls and he loved to pull funny stunts. But his idealism, surely picked up

Helen Marie with sister Joan and brother Jack at ordination of Father Tom Clarke S. J. – 1950

from his family, from the Sisters at St. John the Evangelist School, and from his association with Dorothy Day at the Catholic Worker House, led him to join the priesthood.

Every three years Uncle Jim, now known as Father Martin de Porres Clarke, came home from Japan to New York on a three-month's leave of absence. He was so beloved by his former colleagues with the New York City Fire Department that they organized a “Bucket Brigade” and raised funds for his mission in the poverty-stricken Ryukyu Islands of Japan, where the U.S. Okinawa naval base dominated. A large freman's boot was placed on the bar at P. J. Clarke's to encourage customers to make contributions to Uncle Jim's mission. It was my father who took care of the funds donated to Uncle Jim. Dad would come home from his job and go immediately to his desk and start writing thank-you notes to the various donors. In this way, Dad was united with Uncle Jim and his work in Japan.

Uncle Jim made the New York Times front page when he was instrumental in getting the Japanese government to accept a Vietnamese boat family—the only time Japan allowed this to happen. Jim loved the Japanese people, and, while he did not succeed in baptizing many, he was very happy that he helped them get decent housing and health care. Always proud of his family and their simple life over the bar, Jim died in New York City in l995 after serving there for several years as a hospital chaplain. As he aged, Uncle Jim's face became riddled with laugh lines—he was the chief comedian in the family, but his brother Charlie was a close second.

Uncle Tom, the Jesuit priest, was away a great deal from New York City, but he stayed very close to my mother and father by mail. As the most brilliant brother, Uncle Tom could fill a book listing all his accomplishments as a writer, theologian, and retreat director, but all the Clarkes would agree that his epitaph could best have been “He loved his family.” Uncle Tom was ever proud of his Irish origins, and he made visits to both maternal and paternal relatives in Ireland. Dad liked to recall the day when some of his younger brothers were playing on the stairs at the saloon and they rolled their brother Tom down to the basement and thereafter always laughingly claimed that the bump on his head was what made Tom so smart.

Despite living above a saloon, only one of the Clarke boys, Charlie, followed Uncle Paddy into the bar. Returning from World War II, Charlie took on the role of manager for Paddy and then remained the manager until his retirement in l989. I have fond memories of joining my dad and Uncle Charlie for a night at the Roosevelt Field “trotters” racetrack—we would place a bet at the $2 window and, if we won, the money would go toward pizza after the races. After Uncle Paddy's death and the sale of Clarke's bar in l948, Uncle Charlie's warm welcome was the major reason we continued to visit 55th Street, the term my family used to refer to the saloon. His sense of humor will long be remembered by his seven children and by hosts of customers and employees at P. J. Clarke's.

And, finally, there is Uncle Ray, my only uncle still alive, who always appreciated how good my father was to him. Living in Flushing, New York, as a widower, Ray is cherished by his children and grandchildren. He had two careers in his life—as a detective and then with special services at the NYPD, guarding important visitors to New York. Later Ray served as the chief of security for RCA at Rockefeller Center.

A favorite story of Uncle Ray's was the time when he was standing with his father, James, at the bar at Clarke's. A drunk was giving his brother Charlie, manager of the saloon, a very hard time. All of a sudden Grandpa Clarke, who had muscles from steamfitting, reached over and hit the man with one arm. The inebriated man was knocked over, and that was the end of the trouble for Uncle Charlie that night.

Ray and his wife, Mary, had a very happy marriage and opened their home to many, many people. On Sunday mornings, all the married uncles would bring their children to Uncle Ray's house, where he would cook breakfast and Aunt Mary would charm all of us with her warmth. My dad loved playing with all his nieces and nephews who numbered nineteen in all, plus his own three children, making a total of twenty-two grandchildren for Grandpa Clarke, several of whom worked part-time at P. J. Clarke's during their college years.

Before he died, Dad gave me his impression of life over P. J.'s. He said he never forgot his origins in that saloon, sitting next to the 3rd Avenue Elevated line, where he had enjoyed the kindness of his mother, the camaraderie of his brothers, the dedication of his father and uncle, the fellowship of people at the bar, and so many happy family gatherings. Throughout his life, Dad was a devoted Catholic like his Uncle Paddy and his parents; he was egalitarian in his approach to people, accepting them for who they were, something he picked up from being around a saloon.