‘Against our honesty is set dishonour, against our faithfulness is set treachery . . . ’

—George VI, 24 May 1940

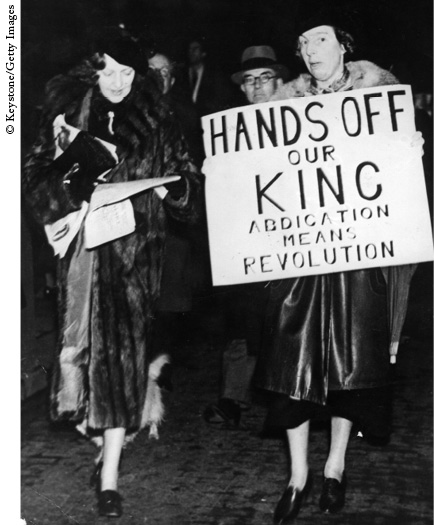

The case of the vanishing duke was pursued with great vigour but scant regard for the truth by certain sections of the press. The duke and duchess were not at their château near Antibes by the sea or in Biarritz. In Italy there were reports on 20 June 1940 that ‘Winston Churchill has ordered his arrest on grounds that he “showed a hostile attitude”’.1 Il Messaggero in Rome raised the prospect that ‘the duke might again become King under an Italo-German conquest of Great Britain’.2 Later reports claimed the British Army had already ‘risen against King George and was demanding the return of the Duke of Windsor to the throne’. The New York Times soberly brought an end to the conjecture on 21 June with the news that ‘24 hours of speculation as to their whereabouts’ had closed that morning when the duke and duchess surfaced in Barcelona.3

The duke took the trouble on 21 June to telegraph news of his safe arrival to Churchill. ‘Having received no instructions have arrived in Spain to avoid capture. Proceeding to Madrid. Edward.’ Helpfully his telegram stated: ‘His Royal Highness is at the Ritz Hotel.’ 4 Churchill’s swift reply was unambiguous. ‘We should like Your Royal Highness to come home as soon as possible.’ 5 But the former king was in no hurry to return home. The fate of Britain was unknown, and if it did fall, there might, at last, be a role for Wallis and himself. On 23 June, he and his wife stepped through the polished doors of the stunning baroque palace of the Ritz in Madrid. The capital had suffered heavy bombing in the Spanish Civil War but in the fashionable heart of the city the Ritz had been renovated and was ready to welcome any visiting aristocracy.

Joachim von Ribbentrop knew exactly where the Windsors were staying and began to glimpse an exciting way to enhance his position with Hitler still further.6 The German Foreign Minister was heady with the victories of the last few days. Waiting at Hitler’s side in the bright sunlight outside the French Armistice wagon had been a moment to savour. Hitler had chosen the exact site for the Armistice ceremony in the Compiègne Forest north of Paris where Germany’s humiliating defeat had been signed in 1918. But this time roles were reversed. The French arrived, their faces like stone. Inside the wagon Hitler, Ribbentrop, Goering and Hess could scarcely suppress their excitement as the terms were read out. A vast swathe of north and west France, including Paris and all Channel and Atlantic ports, would be occupied by the Germans. The 84-year-old French Marshall Henri-Philippe Pétain would run the remaining two-fifths of unoccupied France. Almost two million French men became prisoners of war.7 Ribbentrop basked in the glory of the German victory parade in Paris as an unending train of armed Aryan youth marched down the Champs-Elysées against a backdrop of a giant swastika unfurled from the Arc de Triomphe. Now, away from public view in his army headquarters, Ribbentrop could see a route to even greater personal triumph through an intriguing telegram marked ‘Strictly Confidential’. It was from yet another resourceful German ambassador—this time in Madrid. Dr Eberhard von Stohrer’s missive concerned the Duke of Windsor. Should we ‘detain’ the duke in Spain, Stohrer enquired?8

Ribbentrop knew how keenly Hitler wanted to settle ‘the British question’ so that he was free to pursue his interests in the east. He believed that Britain must want peace and could see that the pro-German, pro-peace, ex-king could be a trump card—one that he was uniquely placed to play from his earlier acquaintance with the duke and duchess. Knowing the duke’s ardent desire to re-establish a role for himself, he might be a pliable collaborator. Would he collude with the Germans in the same way that Major Quisling had in Norway? The duke had once enjoyed a tremendous following. It was probable the British would take their former much-loved Prince of Wales back to their hearts. The duke’s appearance in Spain was extremely convenient. Although Spain was neutral, under the right-wing dictatorship of General Franco it was ideologically aligned to Nazi Germany and harboured many Nazi supporters—the perfect milieu to establish contact.

‘Is it possible in the first place to detain the Duke and Duchess of Windsor for a couple of weeks in Spain?’ Ribbentrop replied to Stohrer. A little trouble with their exit visas could perhaps be discreetly arranged with the Spanish authorities, he suggested. He was anxious to ensure that no suggestion appeared to come from Germany.9

Ribbentrop need not have worried. The duke himself was in no rush to return home despite Churchill’s order. Now of all times, with Britain on the point of invasion, he decided to make a stand with the palace. For all his grand pronouncements about world peace, he felt himself unable to make peace with his family, unless his conditions were met. Status and prestige was high on his list of requirements. For himself, the duke wanted a suitable appointment. And for Wallis, exactly the same treatment by the palace as the Duchesses of Gloucester and Kent. ‘My wife and myself must not risk finding ourselves once more regarded by the British public as in a different status to other members of my family,’ he insisted to Churchill on 27 June.10 Money once more loomed large in his thoughts. Any increase in taxation because he was no longer living overseas must be compensated with additional income from public funds.11 Telegrams flew back and forth between London and Madrid, with both sides uncompromising.

The British ambassador in Spain, Sir Samuel Hoare, found he had his work cut out keeping the Duke of Windsor on message. It was widely rumoured that he was in Spain to facilitate peace moves and the duke’s indiscretions soon reached not just the British, but the Americans as well. The American ambassador in Spain, Alexander Weddell, was sufficiently shaken by the Windsors’ forthright views expressed to a member of the embassy staff that he alerted the US Secretary of State, Cordell Hull: ‘The most important thing now to be done was to end the war before thousands more were killed or maimed to save the faces of a few politicians,’ the duke had declared. The duke believed that countries that had not prepared for war should not embark on ‘dangerous adventures’. His wife went even further. In Wallis’s opinion, ‘France had lost because it was internally diseased.’ She believed that a country that was not in a position to fight ‘should not have declared war’. Weddell shrewdly pointed out to the Secretary of State that these views reflected an ‘element in England, possibly a growing one’ who support Windsor and ‘who hope to come into their own in event of peace’.12

The Germans, too, were not long in getting the complete measure of the situation. Stohrer, working with supreme efficiency through Spanish intermediaries, reported accurately to Ribbentrop on 2 July that Windsor would not return to England unless ‘his wife was recognised as a member of the royal family and if he was appointed to a military or civilian position of influence . . . Windsor has expressed himself . . . in strong terms against Churchill and this war . . . ’ he explained.13

It had taken barely a week for the duke’s ill-judged stance, aired liberally in Madrid, to reach London, Washington and now Berlin—where Ribbentrop saw a great scheme to bend the duke’s grievances to his own advantage.

‘We are now alone in the world waiting,’ the king confided to his diary. It was pouring with rain in London when he learned of the French capitulation. ‘The news from France could not be more depressing.’ 14 The world was waiting to see if Britain would make peace with Germany. Churchill did not waver. He ordered the Foreign Secretary to ensure that all public officials were ‘strictly forbidden’ to talk of peace.15 The public were behind him. ‘After eight months of wondering what the war was about, the people suddenly knew what to do,’ observed one journalist, George Orwell. ‘It was like the awakening of a giant.’ 16 Resilience—even humour in adversity—was characteristic of the time. ‘French sign peace treaty. We’re in the finals!’ proclaimed one newspaper on 18 June. ‘And it’s to be played on the Home Ground,’ quipped a commissionaire in one of London’s smart clubs.17

But the people of Britain knew they were vulnerable. Blitzkrieg was another name for obliteration. They were ill-equipped and ill-prepared: a nation of shopkeepers Napoleon had called them, but it had fallen to this generation to be tested in this new and terrible way and somehow win. With the country facing a very determined aggressor, renewed effort was put into defence. The king began by parting company with his Lord Steward, the brother of the Duchess of Gloucester. ‘Walter Buccleuch came to say good bye,’ the king entered in his diary on 26 June. ‘It was a rather painful interview as he has been “dubbed” as being pro-German in his attitude towards the War & has said stupid things, but we parted amicably.’ 18 The king’s new Lord Steward was a man of impeccable reputation: the 14th Duke of Hamilton, formerly the Marquis of Clydesdale. The dashing Hamilton, known to the public for his daring flying exploit over Everest, had also become the youngest squadron leader of his day in 1927, taking on the City of Glasgow Squadron. His three brothers commanded squadrons and Hamilton was now in command of air defence in Scotland and the Air Training Corps. A man of such apparently loyal fighting pedigree appeared much more suitable to represent the Royal Household.

Buckingham Palace’s gracious spaces were being transformed as it became a stronghold for royal resistance. Judging by the accounts of Uncle Charles and ‘Cousin Wilhelmina’—as she now was known—the monarch was a likely target in the early hours of any invasion.19 The king, however, was determined to remain in London with his ministers and Elizabeth would not leave him. The maids’ quarters in the basement were adapted into a more permanent shelter, with steel supports to give a measure of protection against a direct hit and wooden partitions to create small chambers for staff. The furniture did little to add to the comfort. It was an incongruous mixture of objects deemed to be essential, including, oddly, axes fixed to the wall, and items judged too precious to leave in the rooms above, such as a collection of antique clocks whose ticking did nothing to ease the nerves in long hours spent underground.20 There was barbed wire thick as hedges in the palace grounds and a shooting range where the king and his staff practised daily. Elizabeth too, abandoning her usual soft pinks and lilacs for shooting gear, took lessons at the range in firing a pistol. ‘I shall not go down like the others,’ she said valiantly.21 A feeling of security was finally established with armoured cars on standby at the palace and an escort selected from the Brigade of Guards and the Household Cavalry.

Still doubtful about the royal defences, Uncle Charles suggested that the king should test the procedure in the event that German commandos parachuted over Buckingham Palace. Full of assurance, George VI sounded the alarm and the two kings retired to the palace gardens to watch acclaimed British security in action.

There was silence. To George VI’s embarrassment, no guards appeared. Nobody was interested in the alarm. He sent for an equerry who returned apologetically to explain that there was no response since the police officer on duty ‘had heard nothing’ of any attack. Once the police realised the king wished to test the procedure, guardsmen duly obliged and began to search the palace gardens for parachutists. But they did not look quite ready to take on crack enemy commando teams. They were more reminiscent of a hunting party in the country approaching the herbaceous borders ‘like beaters at a shoot’. Suitably warned, the king made arrangements to strengthen safety measures.22

There were moments of relief from the unremitting bad news from the Continent. The king was pleased to congratulate three officers who, by some miracle, had escaped from Calais, slipping across to Dover in a motorboat: Captain Williams, Captain Talbot and Lieutenant Millett. They described the scene as Calais fell. The Rifle Brigade had sustained the most casualties. Those who survived were taken prisoner. Brigadier Nicholson, who Churchill had instructed to hold the line, was still alive. He was last seen being whisked away by the Germans in a car.23

The queen, determined to play her part, visited hospitals treating the wounded from Dunkirk. ‘Sometimes one’s heart seems near breaking under the stress of so much sorrow and anxiety,’ she confided to Eleanor Roosevelt. It was unbearable to ‘think of our gallant young men being sacrificed to the terrible machine that Germany has created’. It made her angry, she admitted, but also ‘when we think of their valour, their determination and their great grand spirit, pride and joy are uppermost’.24

Keen to understand how ready the army was to face combat with the enemy and knowing it had been forced to abandon most of its equipment in France, the king discussed the military situation with Gloucester. George VI already knew from his daily briefing papers some 90,000 rifles, 1,000 guns, 2,000 tractors, 8,000 Bren guns, and 400 anti-tank weapons had been left behind on the Continent. ‘No wonder there is a difficulty in re-equipping the BEF,’ he thought.25 Churchill estimated across the whole country there were no more than 200 medium or heavy tanks. More worrying still, it was known that the British Army lacked heavy weapons.26

Gloucester toured British bases, welcomed Canadian and Australian divisions and endeavoured to do his best to create that indefinable morale-boosting quality that a royal visit could inspire. He was soon able to report back to the king on the resourcefulness with which defences were being formed. Miles of coastline were eerily transformed with coils of barbed wire, mines and improvised barriers such as layers of scaffolding to protect against an amphibious assault. Thousands of concrete pillboxes were hurriedly built in June. Like toy bricks dropped randomly by giants, anti-tank obstacles and concrete bollards were placed on roads and railway lines. Ingenious schemes such as oil defence were proposed to compensate for the shortage of weapons. If the German troops tried to land, oil could be pumped through fuel pipes installed on target beaches and set alight. The king knew that everything his practical brother described would be accurate, but barbed wire, pillboxes and scaffolding on the beach did not seem enough.

Neither did the tens of thousands of men aged between seventeen and sixty-five not already in military service who hurried to sign up to the Local Defence Volunteers. This ‘Dad’s Army’, initially equipped with a generous provision of wartime spirit but not much else, rehearsed sometimes bloodthirsty solutions to help them obstruct the enemy: pitch forks, golf clubs, homemade Molotov cocktails and even potatoes studded with razor blades. Roadblocks were set up and eagerly manned. In the open countryside, enemy aircraft attempting to land would encounter further snags in the form of sharp stakes and awkwardly placed farm machinery.27

The Duchesses of Gloucester and Kent joined in the vast effort, visiting first-aid posts, hospitals, the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) and the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS) whose numbers were growing fast as women hurried to help their men. Women assisted with everything from parachute packing and manning of barrage balloons in the WAAF to driving, signalling and loading torpedoes into submarines in the WRNS. Despite the fear of parachutists aiming to seize the royal family, the only change that Alice noticed to her security procedure was the addition of a detective, who moved into Barnwell with his family. He was at her side for every official visit and she soon had a nickname for her loyal escort: ‘the faithful Corgi’.28

As a welfare officer in the RAF, the Duke of Kent gained a bird’s-eye view of Britain’s air defences during June of 1940. The airfields were camouflaged and difficult to find. In the maze of English country lanes it was easy to be lost or late and such was the terror of Germans emerging from nowhere in disguise that if he stopped to ask for directions, villagers would invariably plead ignorance at the sight of a stranger. ‘Careless talk costs lives,’ declared the posters. The press was prohibited from revealing the movements of the royal family, but none the less he was recognised and this, too, could cause delays. One ardent royal enthusiast was determined to show him he had no fewer than three photographs of the Duke of Kent in his front room. When he finally reached his destination, sentries with fixed bayonets at RAF station entrances ordered him to halt and could take precious minutes to satisfy themselves that he really was the Duke of Kent.29

With a full engagement diary he soon understood the intimidating odds for the RAF. The Luftwaffe, heady with victories in France, had almost double the number of aircraft. German airfields were now established within striking distance of Britain in a sweep of conquered lands from Norway to Brittany in France. The French campaign had taken a devastating toll. There was a desperate shortage of pilots; Fighter Command had lost sixty pilots during the Dunkirk campaign alone.30 Britain was down to 700 fighters, although they were being made at the formidable rate of 470 a month.31 There were grave fears the Germans could win this battle simply by wiping out Britain’s radar stations, airfields and aircraft factories. Britain’s famous Royal Navy surely would not hold out indefinitely if the Luftwaffe won victory in the skies?

Kent began to familiarise himself with the different divisions: Fighter Command, Bomber Command, Coastal Command, Flying Training Command, Maintenance Command and even Balloon Command. Defending Britain required a herculean feat of organisation. Once enemy aircraft were detected, 30,000 observers, many of them women, would track them, estimate their numbers, height and position and pass the information to Fighter Command. With intense practice, it took just six minutes from the initial radar detection to getting British fighters in the air heading for the target. The Duke of Kent, once a party man, was now totally immersed in war work; his diary no longer filled with social engagements but tours of duty. He had been dismayed at the conditions existing for the air crews at the start of the war and did all in his power to make life easier for them. His work, quite often hazardous, had taken over his life. He even offered to open his home just outside London to pilots and crews hoping that Coppins would be a refuge where they could at least enjoy a meal, play the gramophone and have some sort of rest. The only drawback, he thought, was that Coppins was close to RAF Northolt and RAF Uxbridge and could be rather noisy.32

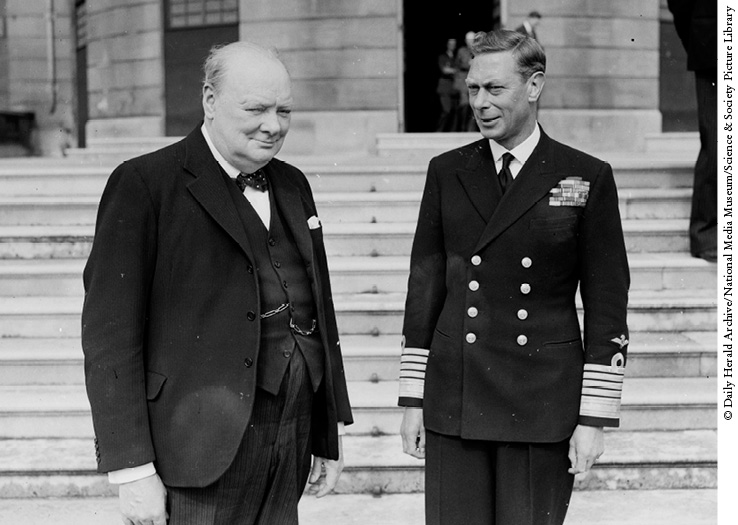

Churchill’s words captured the spirit of the times. Britain would fight, ‘if necessary for years, if necessary alone’ (his italics).33 Indefatigable, the prime minister appeared on Pathé newsreels to be everywhere, always at the centre of a crowd, his sturdy frame walking faster than his years would suggest, his smile reassuring, his bowler hat sometimes raised on a stick, a token of the man, as his short stocky figure was swallowed up by the press of people. He did appear to stand alone, as though holding some private imaginary flag erect, never wavering, carrying the country. He was the figure of certainty: we would win. But to remain optimistic at such a time of dire uncertainty would make costly demands on a man no longer young.

While to the outside world Churchill the leader was beginning to assume iconic status, Churchill the man was feeling the pressure. Behind the scenes, the king was not the only one who ‘did not find him very easy to talk to’, as he confided to his friend Halifax.34 All was not well in Churchill’s ‘private paradise’, Chips Channon deduced after learning of the squabbles between ministers.35 Churchill’s wife, Clementine, went even further. She tore up the first draft of her message to her husband but then had a change of heart and felt she must send it: ‘My darling, I hope you will forgive me if I tell you something that I feel you ought to know,’ she wrote on 27 June. An unnamed colleague in his entourage had been to see her, she explained. She understood ‘there is a danger of you being generally disliked by your colleagues and subordinates because of your rough, sarcastic and overbearing manner’. She warned him that people were finding his ‘irascibility and rudeness’ hard to bear and that she herself had ‘noticed a deterioration in your manner and you are not so kind as you used to be’. She knew this was out of character. Previously his staff had always reported ‘loving you’. But now she warned him of creating ‘a slave mentality’ in his subordinates. If orders were bungled, ‘except for the king, the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Speaker, you can sack anyone and everyone. Therefore with this terrific power you must combine urbanity, kindness and if possible, Olympic calm.’36

Churchill took his wife’s criticism generously but the pressures were immense. How was Britain going to win and with what? The Americans would not join the fight and requests for American destroyers were refused, but they were prepared to help with ammunition, rifles and field guns.37 Churchill requested that a chart was made up of the thirty army divisions to follow their progress to complete equipment. Each division was represented by a square, subdivided to represent rifles, guns, gun carriers, anti-tank rifles, anti-tank guns, field artillery, and transport. Only when certain targets were reached could each square of the chart be painted red.38

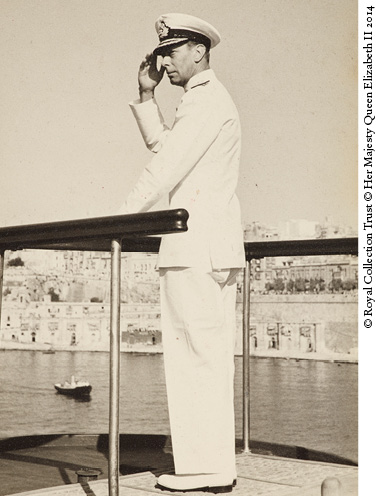

The prime minister wanted not just America, but the whole world, to see that Britain would fight on. Even small neutral states within Europe were courted in an effort to stop them aligning with the Axis powers. The Duke of Kent played a part in this initiative, leading the British delegation to neutral Portugal in late June. The official reason for his visit was to celebrate the 800th anniversary of the foundation of the Portuguese State and the duke arrived on 26 June to find the whole country in a carnival atmosphere. Church bells rang out, bullfights were staged, a medieval pageant of Portugal’s seafaring history was re-enacted through Lisbon by torchlight. Publicly out came the old familiar charm as he entertained ministers, viewed exhibitions and attended a banquet as a guest of the President of Portugal.39 Privately, he did his best to reassure the Portuguese prime minister that the English cause was not lost. Britain would do all in its power to support the neutral countries of Europe.

One of the most testing decisions of British resolve was how to deal with the French navy. If this fell into German hands, it would erode Britain’s margin of safety at sea. The dangers would increase dramatically for merchant ships and convoys in the Atlantic; the Admiralty were arranging crucial American rifle convoys. If the French would not bring their ships to British ports, the War Cabinet concluded the French fleet had to be seized, disabled or destroyed. For Churchill, it was ‘a hateful decision’.40

The largest concentration of French vessels was in the Mediterranean at the port of Mers-el-Kebir on the coast of French Algeria. Negotiations were protracted. The French would not agree to British terms. By late afternoon on 3 July the atmosphere in the Admiralty and the War Cabinet was tense, Churchill following proceedings closely. At 5.54 pm the British opened fire on the French. The battleship Bretagne was soon ablaze, and five other ships were damaged. Some 1,297 French sailors lost their lives that day. For Churchill, this grim strike at Britain’s ‘dearest friends’ was essential. ‘It was made plain the British War Cabinet feared nothing and would stop at nothing.’41

Queen Elizabeth, feeling rather braver than could be discerned from her charmingly draped and befurred image, summed up the mood in a letter to Mrs Roosevelt. ‘We are all prepared to sacrifice everything in the fight to save freedom.’42

The Duke of Windsor was finding much to enjoy about life at the Ritz in Madrid. Inexplicably he found himself the sudden centre of interest, with Spanish leaders and nobility keen to pay court. He renewed his acquaintance with his cousin, Prince Alfonso, 6th Duke of Galliera, a great-grandson of Queen Victoria who also shared his passion for flying.43 Oblivious to the insensitivity, he also spent time with the Civil Governor of Madrid, Don Miguel Primo de Rivera, leader of the local Falangists—the official Spanish Fascist party—who was eager to escort the Windsors—a liaison duly noted by the New York Times as ‘Windsors Dine with Fascist’.44

Almost farcically, while the Germans were using the Spanish to establish contact with the Duke of Windsor, he, in turn, was trying to establish a link with the Germans and the Italians. The Windsors’ two homes in France, each a little shrine to the exquisitely civilised, were causing concern to Wallis. Would their lavish collections of fine art, silver, and other treasures be safe from looters? Apparently oblivious to the fact that he was seeking favours from his country’s enemies, through an intermediary the duke asked officials at the German embassy in Madrid to protect his house in the Boulevard Suchet in occupied Paris. Ribbentrop was delighted to oblige. A teletype survives from Ribbentrop’s office giving orders on 30 June to undertake ‘unofficially and confidentially an unobtrusive observation on the duke’s residence’ and instructing the German ambassador in Madrid, von Stohrer, ‘to inform the duke confidentially through a Spanish intermediary that the Foreign Minister [Ribbentrop] is looking out for its protection’.45 The Windsors sent a similar request through the Italian embassy in Madrid to the Italian government to protect their Château de la Croë at Cap d’Antibes, should the Italians occupy the Riviera.46 It is perhaps a measure of the duke’s detachment from reality that he was prepared to attempt to ask such a favour from the enemies of his country who were busily engaged in all-out war and issuing invasion dates. It was beginning to look as though the duke had other plans.

Meanwhile, the Duke of Windsor’s ill-timed haggling with British officials intensified. Churchill urged him to resolve his problems with his family once he was home, but the duke refused to return unless ‘I know the result’.47 For the duke it was a matter of honour. He could not see that he was indulging in a form of emotional blackmail; all he could see was the humiliation for Wallis if no one from the royal family acknowledged her. After arguing with the Windsors ‘for hours on end’, by the end of June the British ambassador, Samuel Hoare, told Churchill there was only one outstanding issue on which the couple would not back down. They wanted assurances that on their return their place within the royal family should be confirmed, even if it was just a token gesture: to be received by the king and queen at the palace and to have this announced in the court circular. Just fifteen minutes of the king and queen’s time could resolve this dangerous rift, Hoare reasoned.48

It was too late. The harm had been done. The Duke of Windsor’s negotiations at this most difficult of times had undermined the king. George VI did not feel equal to the task of managing his wilful older brother if he returned to England. What sort of king would he be with the Windsors forever at his heels with veiled threats and impossible requests? Having talked it over with both his mother and his wife, the king was resolved and would not compromise. When he met the prime minister on 3 July he spoke frankly: ‘I did not see what job he could have in this country & that “she” would not be safe here.’49 George VI was so convinced that Wallis lay behind his brother’s bad behaviour that he could not bring himself to use her name in his diary, referring to her simply as ‘she’. Winston had always been Windsor’s friend, but now the king was on first name terms with him. George VI sensed that even Winston’s unending patience with his brother was beginning to wear a little thin.

While negotiations continued over the duke’s future, British officials hoped, at the very least, to move the duke and duchess out of Spain—with its many German agents and sympathisers—to neutral Portugal. They had to wait while the Duke of Kent was in Lisbon; the prime minister of Portugal did not wish to have both dukes in the country at the same time. But on 3 July the Windsors finally arrived in Lisbon where arrangements had been made for them to stay in a villa owned by a wealthy Portuguese banker, Ricardo Espirito Santo Silva. It was a stunning setting, with distant views over the Atlantic, the ceaseless sound of the crashing of waves on rocks down below. But the duke did not have time to take in the beauty of the surroundings. Officials handed him a telegram he would never forget. It was from Winston Churchill.

‘Your Royal Highness has taken active military rank and refusal to obey direct orders of competent military authority would create a serious situation. I hope it will not be necessary for such orders to be sent. I most strongly urge immediate compliance with the wishes of the Government.’50

The duke read the telegram visibly shaken. It was tantamount to a threat of court martial. The marked change in tone from his most loyal ally, Churchill, was a shock. Since the abdication he had counted on Churchill seeing his point of view.

The prime minister’s first telegram was followed swiftly by a second bombshell. There was no longer a demand for him to come home. Instead, he was offered a post as the Governor of the Bahamas.

The duke was stunned. It was a bolt from the blue. In his eyes the Bahamas was one of the least significant spots anywhere in the empire, a coral archipelago in the Atlantic some 150 miles off the coast of Florida. As he read and re-read the telegram he knew at once this was a personal banishment.

‘I have done my best,’ Churchill told the duke, in a ‘grievous situation’.51 For officials in London, there was one overriding question. Would the duke accept?

Shaken by the indignities piled upon him from London, the duke began to see advantages in the position in the Caribbean. He could avoid the shame of returning to Britain a lesser man, his wife’s exclusion from court plain for all the world to see. In the Bahamas, he could keep his pride intact. He could be his own man in Wallis’s eyes, and maintain his distance from George VI and British policy. With great reluctance, he accepted. The Duke of Kent privately expressed the family relief in a letter to Prince Paul of Yugoslavia: ‘to accept to be Governor in a small place like that is fantastic!’52

But it was not long before a disturbing new report reached officials in London, damning Windsor still further. This time, it was not troublesome telegrams from Windsor himself, but British intelligence from a source close to Konstantin von Neurath, a former Foreign Minister of Germany and now Reich Protector of occupied Czechoslovakia. On 7 July Sir Alexander Cadogan, under-secretary at the Foreign Office, received a report of sufficient concern that he passed it up the line and it reached the palace that same day. A handwritten note on the letter also confirms ‘PM to see’.

My dear Cadogan. A new source, on trial, whom we know to be in close touch with Neurath’s entourage in Prague, has reported as follows:

‘Germans expect assistance from Duke and Duchess of Windsor, latter desiring at any price to become Queen. Germans have been negotiating with her since June 27th. Status quo in England except undertaking to form anti-Russian alliance. Germans propose to form Opposition Government under Duke of Windsor having first changed public opinion by propaganda. Germans think King George will abdicate during attack on London.’53

.jpg)

George VI was confronted with evidence that showed the Germans proposed to replace him with his brother. Reading the letter in the palace there were so many questions. How much ‘assistance’ had his brother led them to expect? Was it possible that Windsor would betray his own brother? George VI’s view that ‘she’ lay behind the trouble appeared vindicated by the source. The Germans seemed to recognise what he had long suspected—that Wallis desired ‘at any price to become Queen’. He could only speculate on how the information was reaching sources close to von Neurath. Who was his brother mixed up with in Portugal?

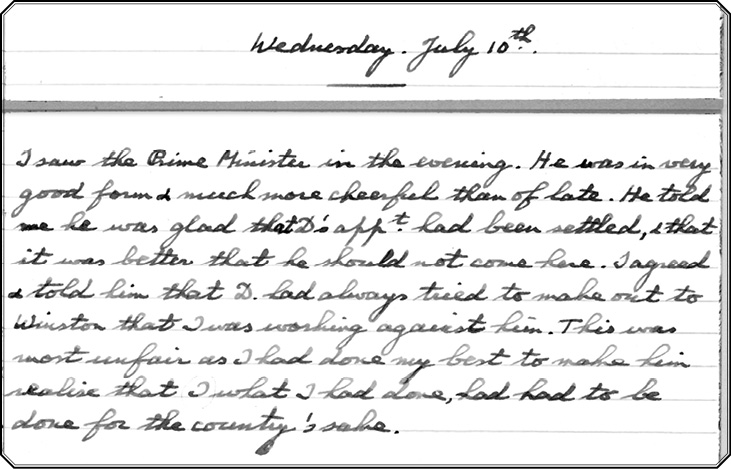

When the prime minister next came to Buckingham Palace, on 10 July, the king found, with some relief, that he and Winston could at last begin to see eye to eye on the issue of his brother. Winston, who had always extended the hand of friendship and loyalty to the ex-king, appeared to be changing his view and agreed with the War Cabinet ‘that it was better that D [David] should not come here’. The king, in turn, was able to open up a little to his prime minister on this most painful family issue. Instead of being made to feel at fault for what appeared to be an unbrotherly stance, he felt he could explain his position and be understood. ‘D had always tried to make out to Winston that I was working against him. This was most unfair as I had done my best to make him realise . . . what I had done, had had to be done for the country’s sake.’54 Now there was intelligence to support his point of view.

There was a heavy blanket of cloud over the east coast of England at 7.30 am on 10 July 1940 as pilots from RAF Coltishall, near Norwich, scrambled to intercept a lone German reconnaissance plane. This proved to be the opening salvo on a day that would mark the start of the Battle of Britain as Goering’s Luftwaffe intensified the bombing of convoys in the Channel. At 1.50 pm the ominous sound of German bombers filled the air off the Kent coast. With a deafening crescendo suddenly more than sixty enemy aircraft were directly above the biggest convoy sailing that day, codenamed ‘Bread’. It was the biggest formation yet crossing the Channel, the ships below desperately dispersing as bombs fell. British fighters roared into attack against German bombers. A maze of vapour trails circled high above the ships as planes soared and plunged above them.55 Although success that day went to the RAF, it was a menacing foretaste of what the Luftwaffe had in store for Britain’s Channel convoys, the lifeblood of the country.

While the Luftwaffe gave Britain a warning of Hitler’s intent, Ribbentrop hoped he might have a rather more brilliant solution to ‘the British problem’ which would upstage his rival, Goering, and place him firmly within Hitler’s charmed circle—and Windsor seemed to be playing into his hands. Unchastened by Churchill’s evident displeasure, the duke continued to air his pro-peace, anti-British government views liberally in Portugal, duly logged by staff in the American, British—and German—embassies. Stohrer’s counterpart in Portugal, the German ambassador, Oswald von Hoyningan Huene, sent a confidential memo to Ribbentrop on 11 July explaining that, most conveniently, the duke wished to stay in Europe and delay his travel to the Bahamas ‘as long as possible’. Was the duke buying time while the Germans brought the British to the negotiating table? The German ambassador built a portrait of an ex-king who was now ready to betray his country and who was being sent away deliberately so that he could not provide leadership to the peace movement in Britain. The duke ‘is convinced that if he had remained on the throne war could have been avoided, and characterises himself as a firm supporter of a peaceful arrangement with Germany’, concluded Huene. ‘The duke definitely believes that continued severe bombing would make England ready for peace.’56 For Ribbentrop, here at last was ‘the king across the water’, apparently willing to negotiate as soon as the threat of heavy bombing brought the proud British nation to the table.

Ribbentrop sent an immediate reply to Stohrer in Spain marked ‘Special Confidential Handling. Top Secret’. The German Foreign Minister had a cunning plan to exploit Windsor’s grievances still further. The first step was for Stohrer to find a way to bring the duke back to Spain where the Germans had more influence. Ribbentrop advised Stohrer that the invitation was best handled by the Spanish: perhaps friends of the duke could find a reason to ask him to return? Once safely in Spain, the duke would be told: ‘Germany wants peace with the English people, the Churchill clique stands in the way of that peace, and that it would be a good thing if the Duke would hold himself in readiness for further developments.’ To achieve peace, Germany ‘would be prepared to accommodate any desire expressed by the Duke, particularly with a view to the assumption of the English throne by the Duke and Duchess.’ Windsor was to be left in no doubt that if he co-operated with Germany, Ribbentrop in turn would help him and the duchess lead ‘a life suitable to a king’.57

Knowingly or otherwise, the duke’s actions continued to support the German plot. He found fresh grounds to pick a quarrel with British officials. Although arrangements were made for him to sail to the Bahamas on 1 August, he threatened not to leave unless his new—and increasingly petty—requests were met. For two weeks angry telegrams were exchanged with London and, once again, Churchill was drawn in. At issue: the duke wanted his personal valet and chauffeur exempted from military service to join him in the Bahamas, an unfortunate precedent to which officials could not agree. The duke had also booked his passage to the Bahamas via New York in order to take his wife shopping and to see her doctor. Churchill would not permit this. There was a risk the duke would rally the cause of peace during the critical build-up to the American elections in November. When the Foreign Office went to the lengths of arranging for his ship, the Excalibur, to be diverted to Bermuda rather than stop in New York, the duke was incensed and wrote to Churchill in strong language, threatening resignation.

The duke was keen to please Wallis, and Wallis, faced with the prospect of travel to some far-flung island, was keen to be reunited with her worldly wealth. Her possessions loomed large in her mind, perhaps all the more important to her while her royal position was so visibly denied. Oblivious to the dangers, it was not sufficient for the Germans to keep watch over her treasures in France, she now wanted her maid, Jeanne-Marguerite Moulichon, to go into enemy territory to collect them. She persuaded the duke to make arrangements for the intrepid Mademoiselle Moulichon to return to occupied Paris to pick up ‘all the Windsor linen’, and other essentials. Her best chef from La Croë should also come with them to the Bahamas. Once again, the duke obliged, despite the fact that this required further co-operation with his country’s enemies.58

Just how was this German co-operation secured? British intelligence had now woken up to the case. Cadogan soon received a report from his source in Lisbon who made contact with a ‘Mr Gray’, described as a tall Englishman with white hair, who was working as a private secretary to Windsor. ‘Mr Gray’, who was in fact ‘Major Gray Phillips’, was indeed assigned the onerous task of overseeing the transport of all the Windsors’ private possessions. Perhaps uncomfortable with the position in which he had been placed, Gray Phillips appears to have confided to Cadogan’s informant the great care with which the Germans honoured the duke’s requests.

‘Special camions were sent to and fro and a detailed inventory list was made of all the furniture and personal property of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor which was shown to the Duchess for approval, to give her the opportunity to say if there was anything missing. Some of the more valuable belongings were transported in limousines and special instructions were given for everything to be in perfect order. The desire of the Germans to please the Duke and Duchess of Windsor was absolutely marked and evident . . . ’59

Cadogan still did not know just how Windsor’s staff were liaising with the Germans. On 19 July this changed, with new intelligence revealing at least one point of direct contact: through the owner of the very house where the duke and duchess were staying. Windsor was seeing a great deal of Ricardo Espirito Santo Silva. ‘We have now learned from a reliable and well-placed source in Lisbon that Silva and his wife are in close touch with the German embassy and that Silva had a three hour interview with the German Minister on the 15 July.’60

This British intelligence once again was duly passed on to the prime minister. Signor Santo had been trusted. He had been permitted to host the Duke of Kent when he had stayed in Portugal. His integrity was accepted in the city and he traded with British banks. But was this the whole story?

Lord Halifax himself took the next intelligence report directly to the prime minister. It presented a very different view of the charming and wealthy Signor Santo: ‘Politically he is a crook. He is handling very large sums in bank notes and dollar securities from Germany via Switzerland to the Americas. These monies are almost certainly German loot from the captive countries . . . ’61

The Holy Fox and Britain’s Bulldog took in the report together. Somehow, under their watch, the ex-king of England appeared to have fallen into the hands of a criminal financier who was reporting his every word directly to the Germans.

In July 1940 Hitler himself had still not given up on the idea of negotiating terms with England. Churchill and his Cabinet supporters’ desire to fight on in the face of glaring military defeat was an anathema. Many in the Nazi leadership still believed in a powerful pro-peace movement in Britain. Goebbels wrote of two parties in Britain: ‘one thoroughgoing war party and one peace party’. Opinion, he believed, ‘was completely divided’.62 Hitler’s defiant address in the Reichstag on 19 July claimed he too wanted peace. ‘Mr Churchill . . . no doubt will already be in Canada,’ he goaded. ‘For millions of other people, however, great suffering will begin.’ He appealed ‘once more to reason and common sense in Great Britain . . . I see no reason why this war should go on’.63

.jpg)

Lord Halifax took the intelligence on Ricardo Esperito Santo Silva directly to the Prime Minister. The British now believed the owner of the house where the Windsors were staying was a German informant who was ‘almost certainly’ involved in laundering ‘German loot from the captive countries.’ (The National Archives)

Suddenly from New York to Rome a spate of press reports appeared alleging that a new British government was forming around the Duke of Windsor and that George VI might be forced into abdication. ‘The Duke of Windsor has telegraphed King George,’ reported Gazetta del Popolo on 22 July, urging him to form an extraordinary Cabinet ‘to include former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and David Lloyd George as well as Viscount Halifax’.64 ‘Plenipotentiary Cabinet for Britain Urged on King by Windsor’ headlined the New York Times on 23 July, adding helpfully that ‘plenipotentiary’ means the ‘power to negotiate treaties’.65 The Finnish and Danish press also carried reports that the Duke of Windsor and the former Liberal leader, Lloyd George, were working towards a peaceful settlement with Germany.66

Foreign Office officials, eager to damp down reports, concluded it was fraudulent enemy propaganda deliberately exploiting the Duke of Windsor’s stand in Lisbon to try to precipitate a crisis in Britain. The reports were so sensationalist it was decided not to grace them with a denial.67

Lord Halifax, one of Britain’s former top appeasers, was chosen by the Cabinet to give the reply to Hitler’s speech. If he spoke out it would help to dispel enemy propaganda claiming that he still sought to be part of a new ‘peace cabinet’. ‘Peace should be based on justice,’ Halifax declared in a broadcast on 22 July. Hitler’s appeal ‘was to the base instinct of fear, and his only arguments, threats . . . We shall not stop fighting until Freedom is secure.’68

Despite such fighting talk from Britain’s former appeaser, behind the scenes Hitler would not give up his efforts to make contact with those who favoured peace. In late July he made his wishes plain not just to Ribbentrop, but also to Rudolf Hess. In a lengthy discussion which would inspire his slavishly loyal deputy for months to come, he impressed on Hess his keen desire for peace with Britain if he could only find a way to reach the eminent aristocrats and other leaders in British society who had expressed pro-peace views.69 Intriguingly at this time, and almost certainly in a desire not to antagonise Britain’s ruling classes whose support might soon be needed, certain prisoners of war found themselves singled out for favoured treatment. Among the chosen prominente was the queen’s own nephew, John Elphinstone, who had been serving in the Black Watch when he was captured at Abbeville before he could be evacuated.70

But for Ribbentrop, in the high-stakes game of negotiating peace, Britain’s ex-king was the greatest trophy of all. Stohrer, the German ambassador in Spain, chose the duke’s trusted friend, Don Miguel Primo de Rivera, the Civil Governor of Madrid, for the delicate mission of luring the Windsors back to Spain. Stohrer updated Ribbentrop with their plan on 23 July. De Rivera was making arrangements for the duke and duchess to leave Lisbon for a long excursion in the country where they would cross the border at a prearranged location with the help of the Spanish secret police. The duke and duchess ‘very much desired to return to Spain’, Stohrer told Ribbentrop. ‘The Duke was considering making a public statement disavowing present English policy and breaking with his brother.’71

Ribbentrop briefed Hitler on his progress later that evening. Together the leader of the German Reich and his Foreign Minister devised Operation Willi—their codename for the British duke. A young and ambitious SS Brigadeführer, Walter Schellenberg, chief of counter-intelligence for Himmler, was selected to run the operation and found himself summoned urgently to meet Ribbentrop.

According to Schellenberg’s memoirs, the Führer himself gave approval for the Germans to place fifty million Swiss francs at the Duke of Windsor’s disposal, if ‘he was ready to make some official gesture dissociating himself from the manoeuvres of the British royal family’. The Führer—evidently sympathetic to the duke’s little weakness—was quite prepared to go to a higher figure if necessary. The duke was to be set up in readiness as a compliant ‘king across the water’ should his brother prove less than amenable when Britain was brought to its knees. ‘Hitler attaches the greatest importance to this operation,’ Ribbentrop told Schellenberg. ‘He has come to the conclusion that if the Duke should prove hesitant, he himself would have no objection to your helping the duke to reach the right decision by coercion . . . ’ Schellenberg was ordered to outwit the British Secret Service ‘even at risk of his own life’.72

Schellenberg flew on a private plane to Madrid the next day and conferred with the German ambassador, Stohrer, whose plot to lure the duke back to Spain was shaping up well. Stohrer’s confidential emissary had gone so far as to raise the prospect of a return to the British throne by the duke and duchess. ‘Both the Duke and Duchess gave evidence of astonishment’ and told Stohrer’s emissary that this was not possible after the abdication. When the emissary ‘expressed his expectation that the course of the war might bring about changes even in the English constitution the Duchess especially became very pensive . . . ’73

Just how complicit were the duke and duchess in the plot to return to Spain? The duke was an intelligent man. He had had meetings with known Fascists, such as Don Miguel, and had liaised with the Germans successfully through intermediaries over his possessions. He did not co-operate with official British wishes at a time when the country was in dire crisis. Nor did many of his views aired at the time express British policy. And Stohrer, at least, understood that it was the duke and duchess’s ‘firm intention’ to return to Spain.74 It stretches credibility that the Windsors did not know something of what was going on. Even the British ambassador to Spain, Hoare, heard that the Duke was intending to return. According to Stohrer, the Windsors went so far as to secure the necessary travel permits. He informed Ribbentrop that the duke, ‘after energetic pressure, had now obtained through the English Embassy in Lisbon a visa for Spain’.75

To ensure the duke’s continued co-operation, Stohrer sent a skilfully drafted letter to make him fearful of British intelligence while also offering assurance he would be a free political agent in Spain. The letter to the duke included ‘the very precisely prepared plan for carrying out the crossing of the frontier’. Schellenberg meanwhile had arrived in Lisbon to fine-tune the German plan with the Portuguese. Just in case anything should go wrong, a fall-back plan was set in place to enable the Windsors to fly to Spain. Finally, added Stohrer, ‘Schellenberg requests that the Chief of the Security Police be informed of the planning’. Reinhard Heydrich himself, the sinister head of the Gestapo, was to be in on the plot.76

In London in late July, Churchill was preoccupied with the urgent business of bringing an American rifle convoy safely into port. With 200,000 rifles on board, it was the largest consignment of weapons yet. Their loss ‘would be a disaster of the first order’, Churchill warned the First Lord of the Admiralty on 27 July.77 In the midst of preparations, Churchill was alerted to troubling new intelligence concerning the Duke of Windsor. Just how much he knew of the plot brewing in Lisbon is unclear but he did realise that suddenly the duke was unwilling to sail to the Bahamas on 1 August as agreed, and summoned the cavalry in the most unlikely form of Sir Walter Monckton. Churchill judged that the respected lawyer who had navigated the duke through the quicksands of the abdication would be the ideal man to steer him on to the right path once again. Seated in Number 10 before the prime minister, Sir Walter was soon made aware of the gravity of his mission, although this particular brief he would later ponder with some amusement was one of the oddest of the ‘Odd Jobs I have Done’.78 His task: to outwit the enemy and make sure that the duke and duchess sailed on the Excalibur to the Bahamas on 1 August, without fail.

The challenge ahead for Monckton was being made harder by the day as Schellenberg’s team worked tirelessly to convince the duke that his greatest threat came from British intelligence. In Portugal, within the walled gardens of their exquisite seaside villa, Boca do Inferno, the duke and duchess suddenly found they were not enjoying their holiday. Thanks to Schellenberg, the atmosphere was increasingly frightening. One of their Portuguese guards warned the duke of a plot by British intelligence to assassinate him. The duchess received a similar threat hidden in a bouquet of flowers delivered to their residence. Portuguese intelligence suspected a bomb would be planted on board their ship, the Excalibur. The Windsors were left in no doubt their lives would be in danger if they complied with British demands to sail for the Bahamas on 1 August. A stone shattered a window at their villa one night, as though the would-be assassin was trying to break in. A thorough search of the house in the small hours added to the growing unease. When the frightened Windsors suggested transferring to a hotel in central Lisbon, the Portuguese expressed worries about ‘intelligence reports from various countries concerning the hostile intentions of the Churchill regime towards both Windsors’. The duke found himself in the position where he did not know who to trust. There were rather too many suave and well-groomed men for comfort, offering to open doors that promised everything. And the more they pursued their themes, the more his anxiety grew. He began to consider it possible that his once loyal friend, Churchill, did now want him out of the way. Thanks to Schellenberg’s network of spies, there was no shortage of advisers on hand ready to convince the duke that he would be much safer in Spain.79

Sir Walter Monckton was not the usual action hero as his flying boat sped into the bay near Cascais near Lisbon on 28 July. He was in a totally different category to the likes of his adversaries: Reinhard Heydrich, Walter Schellenberg and Joachim von Ribbentrop. These were men whose allegiance could turn on a sixpence, always listening for undercurrents threading through the various plots. The serious, well-meaning Monckton, safe as houses, unlikely to run off with a chorus girl, was a mystery to them. He exuded an air of Britishness; the bowler hat, briefcase and quality overcoat marked him out at a distance as an English gentleman. At close hand, the dark round-rimmed spectacles and neatly combed receding hairline imparted the slightly studious air of an academic. Was he a civil servant? Was he a powerbroker in some subtle form of British disguise? Was he open to offers? He did not look like serious opposition. The 49-year-old lawyer from Kent was not trained in espionage and did not carry a gun. It is perhaps not surprising that his presence soon had Schellenberg foxed.

The head of counter-espionage for the Gestapo could not believe that the man ‘who calls himself Sir Walter Turner Monckstone’ was really a lawyer from Kent. Schellenberg was convinced this was cover and his real identity was more likely to be ‘a member of the personal police of the reigning King by the name of Camerone’, he reported to Berlin on 30 July 1940.80

But whatever his reason for being there, the Germans were soon aware that in the presence of Monckton, the duke’s wavering upper lip had stiffened. He appeared less sure of the future. With just two days to go before the duke’s ship was due to sail from Lisbon, the Germans decided to raise the stakes. It was time to play some key cards: first, the duchess’s hapless maid, Jeanne-Marguerite Moulichon.

Mademoiselle Moulichon had at last reached the Windsors’ house in Boulevard Suchet in occupied Paris where she packed several trunks with the Windsor treasures, including their very costly and luxurious linen. But her plan to take the express train to the south of France in time to reach Lisbon for the departure of the Excalibur was soon in tatters. When the car arrived to take her to the station, the door opened to reveal—not the friendly Spanish officials that she expected, but a German escort. The terrified maid was informed she was detained in France.81 If the duchess wanted to travel with her favourite Windsor linen she would have to wait in Europe for it.

The next card to be played was the duke’s Spanish friend, Don Miguel Primo de Rivera, who was flown to Lisbon at the eleventh hour to try to persuade Windsor to delay leaving Europe. Rivera swayed the duke, using his charm and influence to convince him that the attack on Britain would soon force both the British government and George VI from the country. It would be much better if the duke remained in Europe to act as mediator. Further claims were made about British intelligence plots against the duke. The duke wavered. Don Miguel Primo de Rivera was so convincing that the duke begged Monckton for a few weeks’ delay to gather more intelligence on the alleged British plot against him. It took all Monckton’s persuasive powers to induce the duke and duchess to set sail the next day.82

Ribbentrop schemed to the last. He contemplated abduction, but decided against it, as he needed the duke compliant. Shortly before midnight on 31 July, the night before departure, he was ready to play his ace: the duke’s own host, Ricardo do Espirito Santo Silva. Santo Silva was enjoying a drink at the duke’s farewell party at a local hotel, but was summoned to Huene’s home on Ribbentrop’s orders in the small hours. Huene asked him to reveal to the duke that Germany was determined to ‘force England to make peace’. The Germans wished the duke to keep himself prepared for such an eventuality. ‘Germany would be willing to cooperate most closely with the Duke and to clear the way for any desire expressed by the Duke and Duchess.’83

On 1 August, the morning of the duke’s departure, Santo Silva, duly briefed, had one last exchange with his royal guest. Their conversation was reported back to Berlin by Huene. ‘The duke paid tribute to the Fuhrer’s desire for peace,’ wrote Huene, ‘which was completely in agreement with his own point of view.’ To Santo Silva’s appeal that the duke ‘cooperate at a suitable time to establish peace, he agreed gladly’. But Windsor had decided to wait for the opportune moment and, until then, to follow orders from the British government. To do anything too early ‘might bring about a scandal, and deprive him of his prestige in England’. He was fully prepared ‘for any personal sacrifice’ when the time was right ‘and would remain in continuing communication with his previous host and had agreed with him a code word upon receiving which he would immediately come back over’.84 From the evidence of this telegram, it would appear the duke was fully prepared to facilitate a peaceful settlement once bombing brought the British into talks with the Nazis but until then he would go along with commands from Westminster.

It was 1 August 1940. A large crowd gathered to watch the Windsors’ departure for the Caribbean. They were obliged to wait because Schellenberg plotted to the end to convince the Windsors it was not safe to sail. The duchess was much exercised about her mislaid household goods. Quite apart from the troublesome absence of her maid from Paris, she was divested of other treasures owing to an inexplicable breakdown in one of the cars in their luggage convoy. It took time to make alternative arrangements and then further delays arose as a staged arrest was organised on the ship, with a witness claiming he had seen suspicious evidence of sabotage.85

The Windsors remained fearful, uncertain whether there was a British plot to assassinate them or a German plot to murder them and blame the British. Like canaries in a mine, their staff were required to board first. Monckton escorted the duke and duchess up the gangway. Further reassurance was provided by the Portuguese police who made a full search of the entire ship. There was even an armed officer from Special Branch summoned by Monckton. At last the Excalibur cast off, its dark hull easing down the mouth of the River Tagus towards the open Atlantic.86 Schellenberg watched at a discreet distance as his complex plans dissolved in the mist gathering over the estuary, finally defeated.

With any lingering hope for a negotiated peace through the duke that summer now gone, Hitler instigated Directive 17. The raids on the Channel were just the opening. The Luftwaffe was instructed to crush the RAF with ‘all means at its disposal’. The Battle of Britain could commence. The delay, however, had worked in Churchill’s favour. In just a few weeks, his chart showing his weapons target for the army divisions showed progress in bright columns of red.

But in Germany the idea of an Anglo-German peace agreement was not completely dead. Ribbentrop’s botched effort created an opportunity for the deputy Führer himself. Rudolf Hess thought he might be able to succeed where Ribbentrop had failed. The peace party in Britain could not just vanish. There must be another way of making contact.87

On 8 September, Rudolf Hess’s mentor and personal adviser, Dr Albrecht Haushofer, was summoned to a strictly confidential meeting. He kept a secret record of his discussion with Hess entitled ‘ARE THERE STILL POSSIBILITIES OF A GERMAN ENGLISH PEACE?’. Haushofer spoke his mind, explaining that the British leadership had no confidence in any treaty with Hitler. ‘In the Anglo-Saxon world,’ he told Hess, ‘the Fuhrer was regarded as Satan’s representative on earth and had to be fought.’ Hess would not give up. There had to be another way. He pushed Haushofer for the names of any highly placed individuals that he knew of in Britain. ‘Was there not somebody in England who was ready for peace?’88

Under pressure, Haushofer did come up with a name. Over the following days he worked out a route whereby they might be contacted. On 23 September 1940 his curious handwritten letter was posted to an intermediary in Wembley, a ‘Mrs V Roberts at 6 Hill Croft Crescent’.

My dear Douglo

Even if there is only a slight chance that this letter should reach you in good time, there is a chance, and I am determined to make use of it . . . If you remember some of my last communications in July 1939 you—and your friends in high places—may find some significance in the fact that I am able to ask you whether you could find time to have a talk with me somewhere on the outskirts of Europe, perhaps Portugal. I could reach Lisbon any time . . . within a few days after receiving news from you . . . Letters will reach me in the following way. Double closed envelope. Inside address: Dr A.H. Nothing more! Outside address:

Minero Silricola Ltd

Rua do Cais de Santarem 32/I

Lisbon, Portugal . . . Yours ever A.89

.jpg)

The intended recipient invited for top-secret talks in Lisbon—‘My dear Douglo’—was none other than the king’s new Lord Steward of the Household: Air Commodore Douglas Douglas-Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton.