The Founding Fathers’ United States was a narrow strip of land along the Atlantic Ocean, an agrarian country whose cities were centers of trade, not industry. While that began to change soon after the end of the Revolution, as the Northwest Ordinance opened up vast tracts of the Midwest to settlement, for years western places like Pittsburgh, Detroit, or Cincinnati were small villages, barely more than fortified outposts, situated along rivers and surrounded by forests still largely populated by long-established Native American peoples. As late as 1820, more people lived on the island of Nantucket than in the city of Pittsburgh.

These Midwestern towns were small, but not sleepy. They bustled with an entrepreneurial energy that in some ways was greater, and certainly more single-minded, than in cities back East; Frances Trollope, visiting Cincinnati in 1828, noted with disdain that “every bee in the hive is actively employed in search of that honey … vulgarly called money.”1 At the time, Cincinnati was by far the largest town west of the Alleghenies, a status it retained until the Civil War. Over the next few decades, as millions of migrants moved westward, one city after another emerged along the region’s rivers and lakes, linked first by canals and then by railroads. In 1837, a different, more generous English visitor could describe Detroit “with its towers and spires and animated population, with villas and handsome houses stretching along the shore, and a hundred vessels or more, gigantic steamers, brigs, schooners, crowding the port, loading and unloading; all the bustle, in short, of prosperity and commerce.”2 By the eve of the Civil War, Cincinnati, St. Louis, Chicago, and Buffalo were all among the ten largest cities in the United States.

Most manufacturing in the early years of the nineteenth century was still taking place on the East Coast, in large cities like New York and Philadelphia as well as in dozens of smaller cities around them. Lowell, Massachusetts, and Paterson, New Jersey, were founded as mill towns and grew into cities; the first potteries making tableware were founded in Trenton early in the nineteenth century, while Peter Cooper and Abram Hewitt opened their first iron mill in that city in 1845.3 By the middle of the century, Philadelphia was calling itself the “workshop of the world.”4 These East Coast cities were soon rivaled, though, and in many industries overtaken by the growing cities of the Midwest.

Midwestern cities were hives of industrial activity from the beginning; an 1819 directory of Cincinnati listed two foundries, six tinsmiths, four coppersmiths, and nine silversmiths; a nail factory, a fire engine maker, fifteen cabinet shops, sixteen coopers (barrel makers), and many more.5 Detroit’s shipyards started out as repair yards, soon branched into manufacturing marine engines, and by the 1840s were making steamships for the growing Great Lakes trade. All this activity was fueled by a growing regional market as the population of Northwest Territories exploded. From an 1810 population of 12,282, Illinois’s population reached 1.7 million by 1860, second in the Midwest to Ohio, which by then had over 2.3 million residents. This population explosion was driven not only by continued migration from the East, but also by the arrival of the nation’s first mass immigration, from Germany and Ireland, just before mid-century.

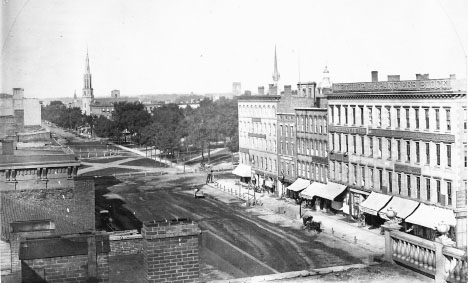

While long-settled cities like Boston and Philadelphia had dignity if not grandeur, Midwestern cities, for all their ambition, were still modest affairs. A late-nineteenth-century description of 1860 Detroit noted that “only a few leading thoroughfares were paved. There were neither street railways nor omnibus lines. Old-fashioned drays did the hauling. There were no public street lamps except in the central part of the city. […] There were but three stone business fronts.”6 Still, there were intimations of greater things to come; pictures of Cleveland from the 1850s, when it was still a small city of only 17,000, show an impressive row of four-story masonry buildings along Superior Avenue leading to the lavishly landscaped Public Square, then and now the heart of the city (fig. 1-1).

Figure 1-1 A city in the making: downtown Cleveland in the 1850s. (Source: Western Reserve Historical Society)

For all the bustle and activity of its cities, though, the United States on the eve of the Civil War was still an agrarian nation. Only one out of six Americans lived in towns of more than 2,500 population. Fewer than 19,000 of Indiana’s 1.3 million people lived in Indianapolis, the state’s largest town; of Illinois’s 1.7 million people, only 112,000 lived in Chicago, the state’s only city of any size, whose economy was still heavily based on meatpacking and other agricultural products, which were shipped back East. Except for a handful of Northeastern mill towns, no American city could be characterized as an “industrial city”; most factories other than textile mills were small in scale, more like workshops than the vast factories that emerged after the Civil War.

That changed quickly. By the late 1880s, the United States had become the world’s leading industrial nation, while in the thirty years following the Civil War, places like Cleveland and Detroit had gone from overgrown towns to become major urban centers. Historians and economists have singled out many different reasons for the simultaneous explosion of industrialization and urbanism in late-nineteenth-century America—so many that one is led to believe that America’s industrial supremacy was meant to be. America had everything: rich lodes of natural resources such as coal and iron; ample and inexpensive energy sources; a far-flung, efficient transportation infrastructure; a growing and increasingly affluent domestic market; transformative technological innovations, such as the Kelly-Bessemer process that turned steelmaking from an artisanal to an industrial process; a flourishing entrepreneurial culture operating with few restraints curbing its activities; seemingly inexhaustible sources of inexpensive immigrant labor; and, of course, the leadership of a powerful band of inventors, financiers, and industrial barons, whose names, whether acclaimed or reviled, still resonate as giants in the American saga: Carnegie, Rockefeller, Morgan, Vanderbilt or Edison.

It wasn’t pretty. Workers worked long hours, under grueling and often dangerous conditions; “you don’t notice any old men here,” said a laborer in Carnegie’s Homestead Mill in 1894. “The long hours, the strain, and the sudden changes of temperature use a man up.”7 In contrast to the small workshops of the past, the new steel mills were vast, impersonal places employing thousands of people. In Carnegie’s mills workers worked twelve-hour days, seven days a week, with only the Fourth of July off. Death and dismemberment were routine daily events. Safety regulations and limits on working hours or child labor were all still in the future.

Living conditions outside the factories were often not much better. With the social safety net also still in the future, poverty and destitution were widespread. Thousands of immigrant families were crammed into tiny houses, often sharing them with one or more other families. While tenements were rare outside New York City, conditions in Baltimore’s alley houses or Newark’s triple-deckers were often only marginally better. In 1900, two or more families doubled up in over half of all the houses and apartments in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Paterson, New Jersey.

Yet that was not the entire story. As the century neared its end, remarkable transformations took place in city after city, particularly in the great Midwestern cities that were at the heart of the nation’s industrial expansion. As these cities’ prosperity grew along with their middle-class populations, they became true cities, not merely in the sense of large agglomerations of people and business activity but, following as best they could the models of ancient Athens or renaissance Florence, as centers of civic, cultural, and intellectual life. While their achievements may have fallen short of those ideals, they were nonetheless notable.

Much of the cities’ efforts were devoted to beautification, often emulating the boulevards and palaces of the great cities of Europe. After Frederick Law Olmsted completed Central Park in Manhattan and Prospect Park in Brooklyn, the next city to commission work from him was Buffalo, followed by Chicago and Detroit. Buffalo, indeed, hired Olmsted to design not only a park, but an entire network of parks and landscaped parkways forming a green ring around this gritty industrial city. Following on the heels of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Daniel Burnham and his colleagues created an elaborate Beaux Arts plan for downtown Cleveland featuring a three-block landscaped mall 400 feet wide, flanked by the city’s principal civic buildings, including the county courthouse, city hall, public library, and public auditorium. During the same years, the great downtown department stores came into being, as did the first wave of skyscrapers, led by the “father of skyscrapers,” Chicago’s Louis Sullivan.

Physical embellishment was matched by cultural embellishment, taking the form of universities, symphony orchestras, and museums, but even more by civic improvement. Reform movements sought to clean up hitherto corrupt municipal governments, ameliorate the living conditions of the poor, introduce proper sanitation, electrify the streets, modernize public transportation, and provide universal public education, introducing all of these features into what had become increasingly polluted and crowded utilitarian places. Lincoln Steffens hailed Cleveland’s Mayor Tom Johnson in 1905 as “the best mayor of the best-governed city in the United States.”8 There was no doubt that the civic leaders of these cities saw them as great cities; as the governor of Illinois said at the 1889 dedication of Chicago’s Auditorium Building, it was “proof that the diamond of Chicago’s civilization has not been lost in the dust of the warehouse, or trampled beneath the mire of the slaughter pen.”9

Beaux Arts schemes like the Cleveland mall may have existed at least in part to burnish the self-image of the cities’ leadership, but the transformation of the industrial city was not merely for the benefit of the elite. Despite—or perhaps because of—sustained labor and civic unrest, the nature of the urban working class was changing. Trade unions were organized, while immigrants became Americanized and their children steadily moved into the middle class. And move they did; as research studies have shown, intergenerational mobility in the United States was at its height from the end of the Civil War to the 1920s, and far greater than in Western Europe at the same time.10 Although it may have become rare for skilled workingmen to open small factories and modestly prosper, the transformation of the American economy had opened up millions of new middle-class jobs for armies of industrial and retail clerks, salesmen and saleswomen, government officials, and the growing ranks of professionals, while factory jobs themselves were increasingly propelling people into the middle class. By 1900, nearly two out of every five families in Cleveland, Detroit, and Toledo owned their own homes, and in contrast to crowded New York City, only one out of eight Detroit families, and one out of fourteen in Toledo, shared their home with another family.

The great industrial cities of the Midwest were only the most visible parts of the nation’s industrial archipelago. During the latter part of the century, manufacturing grew by leaps and bounds, with 2.5 million factory jobs added between 1880 and 1900. In cities as varied as Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and Newark, two out of every five workers worked in factories. By 1900, manufacturing had come to dominate the economies of one-time merchant cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, while hundreds of smaller cities like Trenton, New Jersey, Reading, Pennsylvania, or Lima, Ohio, each had its factories, its immigrant neighborhoods, and its trappings of prosperity in the form of parks, concert halls, and pillared city halls.

Trenton is an archetypal small industrial city. Famous for its role in the American Revolution, its industrial history began in the 1840s with small pottery manufactories, as they were called, and an early iron mill that made rails for the region’s growing number of railroads. As the century progressed, both industries grew. The presence of Peter Cooper’s ironworks brought a German immigrant named John Roebling to Trenton, where he established his own factory for the construction of steel cables; by late in the nineteenth century, over seventy ceramics factories and workshops had been established, from Lenox, makers of fine china, to the predecessors of the Crane and American Standard makers of sanitary porcelain. Other industrial products of the city included rubber tires, canned foods, and one of the sportiest of the early automobiles, the Mercer Runabout. The city’s population grew from 6,000 in 1850 to 73,000 by the turn of the century and nearly 120,000 by 1920, including thousands of immigrants, mostly from Italy and Poland.

As was true of far larger cities, as Trenton grew, it took on the trappings of prosperity. In 1891, Frederick Olmsted’s Cadwalader Park opened to the public, while in 1907, a new Beaux Arts city hall with an imposing marble-pillared façade was dedicated. The city’s sense of itself as first and foremost an industrial city was reflected in the decoration of the new council chambers, which featured a large mural by Everett Shinn, a prominent member of the Ashcan School of American artists. In two vivid panels, it depicts the fiery interiors of the city’s iconic industries, the Maddock ceramics factory on the right, and the Roebling steel cable plant on the left, both all but dripping with the sweat and the exertion of Shinn’s muscular workingmen. About the same time, the local Chamber of Commerce held a competition to coin a new slogan to epitomize the city; the winning entry, “Trenton Makes—the World Takes,” was mounted in 1911 on a bridge across the Delaware River. The same sign, albeit in a new digital version, still heralds one’s arrival in Trenton by train from Philadelphia and Washington.

As Robert Beauregard writes, “the first two decades of the twentieth century, and the latter decades of the nineteenth occupy a privileged position in American urban history.”11 It was not to last. Although it is customary to think of the decline of American cities as beginning after the end of World War II, the first signs of decline were visible as early as the 1920s. One intimation was the growth of the suburbs, as the nation’s transportation systems began to shift from rails and water to a new system based on the car and the truck, the road and the highway. The number of private cars in the United States more than doubled between 1920 and 1925; by 1925, there were over 17 million cars and 2.5 million trucks on the country’s increasingly congested roads, and half of all American households owned a car.

With little fanfare, suburbs began to grow. Earlier streetcar suburbs had remained small, limited to chains of villages along the spokes established by commuter railroads and streetcar lines; now, suburbs could be built anywhere, and they began to fill in the spaces between the spokes, ringing the now largely built-up city with what gradually became a wall of separate towns, villages, and cities locking central cities into their pre-1920s boundaries. While most cities continued to grow during the 1920s, their growth rates were slowing, especially after the drastic restrictions on immigration that went into effect after 1924.

Industry was beginning to disperse as well. St. Louis was the nation’s leading shoe manufacturer, but during the course of the 1920s, as Teaford explains, “St. Louis shoe moguls were shifting much of their production to plants in impoverished small towns scattered through southern Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Arkansas. […] Corporate headquarters would remain in St. Louis and the other heartland hubs, but the corporations’ factories would depart.”12 With water power no longer needed to fuel industry, many of Lowell’s famous textile mills decamped to the South during the 1920s. The city saw its population shrink by over 10 percent during the decade. Although Lowell has been growing again since the 1980s, it has yet to completely regain the population it had in 1920.

The increasingly footloose nature of American industry reflected changes in the structure of the urban economy in ways that marked the beginning of the end for what historian John Cumbler has called “civic capitalism,” or the interconnected network of locally based entrepreneurs and capitalists who were part of the fabric of each industrial city, and who saw their fortunes intertwined with those of their communities.13 As Douglas Rae writes about New Haven, “Beginning even before 1920, a great many local firms, including the largest and most productive, would be drawn out of the local fabric by increasingly muscular and invasive national corporations, … headquartered far from the city, and thus escap[ing] the control of locally rooted managers and owners.”14 While civic capitalism was paternalistic, and often exploitative, it was also linked to the community, not only through companies’ contributions to their city’s physical and social well-being, but also in their economic calculus, which balanced hard economics with local loyalty. Hard economics was on the rise, and local loyalty less and less relevant.

Although these changes were noticed by acute observers in the 1920s, they did not prompt widespread concern. Lowell was an exception. Most cities were still growing, and most had yet to see any significant industrial exodus. Although more and more people were living in the suburbs, their numbers were modest compared to what was to come later, and the great majority of each region’s population still lived in the central city. Suburbanites may have lived outside the city, but they still came downtown to work, to shop, or go to the movies. With automobiles now crowding the streets and new skyscrapers like Cleveland’s iconic Terminal Tower going up, cities seemed livelier and more dynamic than ever.

The next fifteen years, though, were a roller-coaster ride for America’s industrial cities. The Great Depression devastated the cities. As early as July 1930, one-third of Detroit’s auto jobs had disappeared, leaving 150,000 workers idle. Factories were closed, banks collapsed, and homebuilding nearly ground to a halt. By 1933, half of Cleveland’s total workforce was unemployed; as a local newspaperman wrote, “Threadbare citizens daily trooped into newspaper offices, without a dime to buy a sandwich, looking for handouts. The welfare offices were swamped, and unable to furnish emergency relief.”15 As late as 1936, 143,960 people, or one out of every four Buffalo residents, lived on relief or make-work.16

While New Deal programs had begun to alleviate the effects of the Depression by the late 1930s, it was World War II that reversed the downward spiral, though just briefly. Factories that had been idled came back to life. Detroit’s auto industry was retooled to make tanks and airplanes, and the city came to be known as the “arsenal of democracy”; author Hal Borland wrote in 1941 that “this mammoth mass-production machine has a wholly new tempo, a grim new purpose. Smoke rises from a thousand stacks. […] Detroit is busier than it has been for years, and the wheels are speeding up.”17 Hundreds of thousands of whites from Appalachia and African Americans from the Deep South flocked to the city; with little new housing being built, they crowded into existing houses and apartments, built shantytowns, and camped out in city parks.

The thirties and forties were also years of extraordinary turmoil and social change in America’s industrial cities. The 1930s saw the rise of the industrial union through a wave of strikes that often prompted violent responses; the 1937 sit-down strike against General Motors turned the city of Flint, Michigan, into an armed camp, “with more than 4,000 national guards … including cavalry and machine-gun corps.”18 After many such labor battles, unions like the Steelworkers and the United Automobile Workers had firmly inserted themselves into the American economy. By 1943, the UAW had become the largest union in the United States, and by 1949 its membership exceeded 1 million workers.

Violent conflict often also marked the mass migration of African Americans, drawn by the work to be found in the cities and the decline of traditional Southern agriculture. Racial conflict had been a recurrent theme ever since large-scale black migration began during the years of World War I and immediately after, when the Ku Klux Klan found fertile soil in many Northern cities. Tensions simmered in many cities during the 1930s and 1940s, overflowing in Detroit in 1943, when a fight that began in the city’s Olmsted-designed Belle Isle Park triggered three days of violence, leaving thirty-four dead and hundreds injured. It was both the culmination of decades of conflict and a harbinger of what was to come in the 1960s.

As World War II ended and the troops came home, it was not unusual to expect that life and work in the cities would return to normal, which for many people meant life as it had been during the years before the war and the Depression. And so it appeared, at least for a while. Even though, in hindsight, the evidence of urban decline was visible almost from the end of the war, the late 1940s and the 1950s were not bad years for most industrial cities. Factories quickly retooled for domestic markets, and by 1948, America’s carmakers produced over 5 million vehicles, nearly 4 million of them passenger cars. Steelmaking in Pittsburgh was bigger than ever. The Jones & Laughlin Company embarked on a massive expansion of their flagship plant to meet postwar demand, while conversion of plants from coal to natural gas was making the city’s air cleaner than it had been for a long time. Pittsburgh’s notorious pea-soup fogs were becoming a thing of the past. While the number of factory jobs in cities like Pittsburgh and Cleveland fell off from their World War II levels, there were still more people working in those cities’ factories in 1958 than in 1939. And for the most part, they were doing well; as Ray Suarez puts it, “after World War II, the bosses were making so much money that even the workers were in for a taste. Everybody was working, in folk memory and in fact.”19

Housing production picked back up. From the end of the war to 1960, nearly 100,000 new homes and apartments were built in Detroit and even more in Philadelphia. Home ownership took off in the central cities, not just the suburbs. From 1940 to 1960, the homeownership rate in Detroit went from 39 to 58 percent, in Philadelphia from 39 to 62 percent, and in Akron from 49 to 67 percent. In 1960, nearly three out of four families in Flint, mostly headed by men working in the GM plants, owned their own homes, 15,000 of which were newly built in the 1950s.

Neighborhoods seemed largely unchanged from prewar days, and if different, often for the better. In 1960, almost half of all the households in Dayton and Youngstown were married couples raising children (compared to 8 percent today), and most of the rest were married couples who had either not yet had their first child, or just seen their youngest leave the nest. To hear from Suarez again, “the teeming ethnic ghettos of the early century had given way to a more comfortable life, with religious and ethnicity, race and class still used as organizing principles for the neighborhood. The rough edges of the immigrant ‘greenhorns’ were worn smooth, and a confident younger generation now entered a fuller, richer American life.”20

It is easy to romanticize the cities of the 1950s, and Suarez, along with some others who have written about those years, sometimes fall into that trap despite their best efforts. Large parts of the cities were shabby places that had been starved of investment since the 1920s. Most cities were still segregated like St. Louis, where the “Delmar divide,” the unwritten law that no African American could live south of Delmar Boulevard, was violated at peril to life and limb. Yet a strong case can be made that, taken as a whole, the 1950s were the best years America’s industrial cities had ever seen. If the era lacked the raw energy and dynamism of the turn of the century years, it more than made up for it in the far greater quality of life it offered the majority of its residents. Working conditions were far better, and thanks in large part to the growth of unions, wages were higher. Most families now owned their own homes, and doubling up, or taking in boarders to make ends meet, were things of the past.

Yet these thriving cities were dancing on the edge of the abyss, and the signs were there for those who looked closely. The prosperity of the cities reflected the growing prosperity of the nation, masking the reality that their share of the pie had begun to shrink. For all the new houses being built, the cities were drawing few new residents. The 1950 Census marked the population high-water mark for most of America’s industrial cities. While some cities continued to grow or, like Chicago and Cleveland, experienced only modest losses during the 1950s, others saw their population plummet. Milwaukee lost 130,000 people, or 15 percent of its 1950 population, while Pittsburgh and St. Louis each saw their population drop by more than 10 percent.

The nation’s energy had begun to shift irrevocably from the cities to the suburbs and from the old Northeast/Midwest to the Sunbelt. During the 1950s, Houston added 340,000 people, San Diego 240,000, and Phoenix quadrupled its population, with 33,000 new arrivals each year. The 1950s also saw suburban populations begin to outstrip central cities. Up to 1920, central cities typically contained three-quarters or more of their immediate region’s population. The ratio began to shift gradually downward during the 1920s and 1930s, as landlocked cities started to run out of room to grow, but they continued to hold the majority of their regions’ populations. The 1950s, though, were the watershed. For the first time, suburbanites outnumbered central-city residents.

Once the shift had begun, it accelerated. By 1970, cities like Detroit or Trenton each contained little more than one-third of their regions’ populations. Oakland and Macomb counties, the Detroit area’s two outlying counties, had a combined population of less than 130,000 in 1920. That number grew to 580,000 by 1950, but nearly tripled again to over 1.5 million by 1970. Central cities were becoming less and less central.

Many people were aware of what was going on. With New Deal models in mind, the federal urban renewal program, Title I of the 1949 Housing Act, was created to help older cities not only remove slum conditions, but sustain their competitive position as more and more jobs and businesses moved to their growing suburbs. The urban renewal program awarded large federal grants to cities to acquire and demolish properties; reconfigure blocks, entire neighborhoods, or downtowns; and market the land to developers to put up new homes, office buildings, and commercial centers. While the initial impetus for urban renewal may have been to eliminate blighted areas and improve housing conditions, in the course of the 1950s the thrust of the program shifted, and became increasingly aimed at helping cities hold on to their middle-class populations and arrest the decline of their downtowns.

While the principle behind urban renewal reflected a mélange of influences, from the Radiant City ideas of Le Corbusier to the vision of an automobile-oriented future famously presented by General Motors at the 1939 World’s Fair, it was a straightforward one: cities were obsolete. Despite the occasional grand boulevard and the clusters of ornate 1920s skyscrapers, the typical urban downtown was still a crowded collection of smaller buildings, mostly with ground-floor stores and offices above, sitting cheek by jowl on small lots and mostly on narrow streets. In a future where everyone would drive their cars to and from large, freestanding buildings, those crowded cities, with their antiquated infrastructure, needed to modernize to survive. Lots had to be assembled and consolidated into “buildable” development parcels, streets needed to be widened and realigned to allow traffic to move faster, parking garages needed to be built, and above all, the disorder of cities that had grown through accretion since the mid-nineteenth century needed to be replaced with an urban form deemed more appropriate for the modern world.

It was a plausible theory, but it turned out to be a bad one. The fundamental premise that assembly and clearance of large development sites was the key to urban revitalization was fatally flawed; as Jon Teaford wrote, “it taught America what not to do in the future.”21 It was an expensive and painful lesson. Over 600,000 families, mostly poor and many African American, were displaced, often disrupting or destroying neighborhoods that had existed for decades, even centuries, and leaving a lasting residue of anger and resentment.22 Less heralded, but perhaps even more destructive, was the simultaneous construction of hundreds of miles of interstate highways cutting through the hearts of America’s older cities; in contrast to urban renewal, which at least left some historic buildings standing, highway construction destroyed everything in its path, leaving a legacy of fragmented, crippled neighborhoods and downtowns, and new barriers between the survivors.

While the allure of urban renewal had begun to wane by the mid-1960s, the riots that erupted in city after city during those years prompted greater awareness of the intensity of the urban crisis, which led to a host of new federal initiatives. Between 1965 and 1977, the cities were the beneficiaries of more separate federal urban initiatives—the war on poverty, revenue sharing, the Model Cities program, Urban Development Action Grants (UDAG), and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), along with housing programs such as Section 235, Section 236, and Section 8—than before or since. In addition to initiatives that explicitly targeted urban conditions, these years saw a vast expansion of other programs, most notably increases in health and welfare benefits, but also rising federal spending for job training, transportation, community health centers, and education, all directly or indirectly affecting urban America. The mid-1970s were the high-water mark in federal urban spending.

They may also have been the low point in American urban history. These were the years when the phrase “the urban crisis” became part of the American vocabulary. When one thinks about the excitement that people today feel about American cities, it may be difficult to believe how gloomy, even despairing, most people’s feelings about cities were forty or fifty years ago, when a “pervasive sense” existed, as one writer put it, “that cities in America were no longer vital places,”23 and prominent urban advocate Paul Ylvisaker could comment ruefully that “you don’t rate as an expert on the city unless you foresee its doom.”24 In 1971, social critic Stewart Alsop, in a Newsweek column with the foreboding title “The Cities Are Finished,” informed his readers that “the cities may be finished because they have become unlivable; that the net population of cities will continue to fall, … and that the cities will come to resemble reservations for the poor and the blacks surrounded by heavily guarded middle-class suburbs,”25 quoting New Orleans Mayor Moon Landrieu that “… the cities are going down the tubes.”26

Older industrial city populations continued to hemorrhage as more and more families fled for the suburbs or the Sunbelt. In the wake of the riots, white flight became a flood. Detroit’s population dropped by 169,000, St. Louis’s by 128,000, and Cleveland’s by 126,000 during the 1970s. For the first time in the nation’s history, thousands of homes and apartment buildings were abandoned in the hearts of American cities, from the burning tenements of the South Bronx that prompted Howard Cosell’s famous although perhaps apocryphal cry from Yankee Stadium during the 1977 World Series, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning!”27 to the row houses of North Philadelphia and the workers’ bungalows of Detroit.

Smaller cities were particularly hard-hit. East St. Louis, Illinois, across the Mississippi from St. Louis, Missouri, lost 20 percent of its population during the 1970s; in 1981, a reporter could describe “streets steeped in dilapidation, the abandonment distorted and magnified by open lots where houses have been demolished or are burnt-out shells.” By 1985, all five of Gary, Indiana’s, department stores had closed; four were boarded-up hulks, while the fifth had been converted into the county’s department of public welfare.28

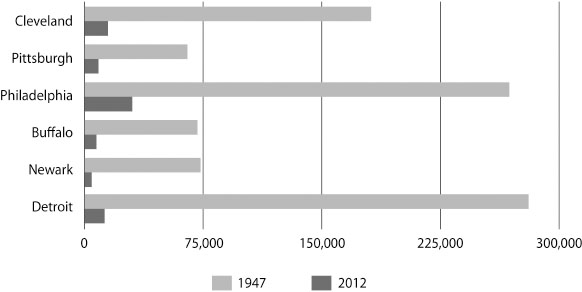

The 1970s were also the decade when the factories closed. In Youngstown, September 19, 1977 is still remembered as “black Monday,” the day Youngstown Sheet & Tube abruptly shut down its plant and furloughed 5,000 workers. Youngstown civic leaders put an ad in the Washington Post begging for President Carter’s help to “keep self-help alive there and in the rest of Ohio,” while others looked for scapegoats, one worker saying “the dirty Japs … killed my father in World War II, and are now taking food from my kid’s table.”29 It was to no avail. Of the 25,000 factory jobs in Youngstown in 1954, only 5,000 were left by 1982. The heartland’s industries—steel, cars, heavy machinery, tires, and more—were cutting back or disappearing in the face of obsolescence and global competition. By the end of the decade, most of the major industrial cities had lost nine out of ten of their factory jobs, as we can see in figure 1-2. Although jobs in retail trade and services were growing, it was not the same thing. The jobs that were gone were those that had defined these cities and created not only a strong blue-collar middle class but an entire culture. Their loss is still felt over forty years later.

Figure 1-2 Vanishing factories: manufacturing jobs in major cities in 1947 and 2012. (Source: US Census of Manufacturers)

The 1980s and 1990s saw a dramatic shift in thinking in America’s increasingly postindustrial cities. As reflected in Youngstown’s civic leaders’ futile appeal, throughout the 1970s cities continued to look to the federal government for help, although as the decade went on, the first rumblings of federal disengagement could be heard. Even before the Reagan Administration had begun to disassemble the nation’s urban programs, the federal government under Jimmy Carter had signaled a reappraisal of the federal role; reflecting their loss of hope for the cities’ future, the President’s Commission on a National Agenda for the Eighties in 1979 called for “a long-term reorientation of federal urban policy” away from “place-oriented, spatially sensitive national urban policies” to “more people-oriented, spatially neutral, national social and economic policies” (emphasis added), admitting that this could have “traumatic consequences for a score of our struggling largest and oldest cities.” In the 1980s, the federal government largely abandoned any pretense of pursuing urban policies, or showing any particular concern for the continued distress of the nation’s older cities. Cities started to realize that they were on their own.

As both the message from Washington and the loss of their flagship industries sank home, cities began to rethink their prospects and the implications of an overtly postindustrial future in which they would be increasingly at the mercy of a shifting marketplace. As often as not, the response was to rebrand the city as an entertainment destination, and, as Kevin Gotham writes, devote “enormous public resources to the construction of large entertainment projects, including professional sports stadiums, convention centers, museums, redeveloped riverfronts, festival malls, and casinos and other gaming facilities.”30 Along with this grew a proliferation of public incentives for private firms and developers, including tax abatements, tax increment financing, industrial revenue bonds, and business improvement districts. All of this activity, coupled with the availability of inexpensive capital and favorable depreciation schedules, fostered something of a building boom in urban downtowns in the 1980s, belying the reality that little had fundamentally changed to justify the boom in either social or economic terms.

While the overall trajectory of the industrial cities continued to be downward, there were a few hopeful signs. While populations continued to decline, the rate of decline was slowing down, and a handful of cities, most notably Boston, even began to regain lost population. Here and there, a major public–private investment took off and began to spin off economic activity, as happened at Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. The Harborplace “festival marketplace,” as its developer James Rouse called it, opened its doors in 1980, and in 1981 attracted more visitors than Walt Disney World.31 It was followed by a Hyatt Hotel, the beneficiary of public financing, and the National Aquarium, funded with a complicated package of federal, state, and philanthropic dollars.

At the same time, small numbers of so-called urban pioneers began to transform dilapidated urban neighborhoods like Baltimore’s Otterbein or Philadelphia’s Spring Garden into enclaves of beautifully restored row houses. Elsewhere in these same cities, newly minted community development corporations took on the daunting project of reviving struggling low-income neighborhoods, not through an influx of urban pioneers but with and through the people who already lived there.

The proliferation of high-profile public–private projects during the 1980s, along with a handful of widely publicized success stories, obscured the reality of continued decline. The failures of Rouse’s other “festival marketplaces,” such as Toledo’s Portside, got less attention than Baltimore’s success. Heralded upon its opening in 1984 as the savior of Toledo’s downtown, by 1990 Portside’s “main entrance … reek[ed] of urine … and the decorative water fountains [were] dry and filled with trash.”32 Later that year, it closed its doors for good.

The cities’ decline was exacerbated by the arrival of the crack cocaine epidemic. Crime continued to rise through the 1980s, peaking in most cities in the mid-nineties, and only then beginning to decline to today’s low levels. Despite the pockets of revival, and scattered cases of “the return to the cities,” throughout the 1990s central-city populations continued to become poorer relative to their suburbs and to the nation as a whole.

Even though revival in America’s postindustrial cities during the 1980s and 1990s was modest and was far outweighed by continuing decline, the trends that were to lead to dramatic change in the new millennium were starting to emerge. When Richard Florida published his influential The Rise of the Creative Class in 2002, talented young people were already flocking to cities like Austin, Seattle, and San Francisco. Florida describes how one gifted Pitt graduate responded to his question about why he was leaving Pittsburgh for Austin: “There are lots of young people, he explained, and a tremendous amount to do, a thriving music scene, ethnic and cultural diversity, fabulous outdoor recreation, and great night life.”33 In 2000, that graduate did not see staying in Pittsburgh as an option comparable to Austin; today that may no longer be the case.

The transformation of America’s industrial cities is not just about what has been aptly called the “March of the Millennials.” Over the past two decades, the United States has seen dramatic changes in demographic patterns, consumer preferences, immigration, and the economy, all of which have affected cities in different ways. Cities like Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and St. Louis are very different places today—for good or for ill—than they were only fifteen or twenty years ago. In certain respects, one can reasonably say that these cities have risen from the ashes of decades of neglect, disinvestment, abandonment, and impoverishment. In others, though, they continue to struggle. Poverty, distress, and abandonment remain very much part of today’s urban reality.

Two fundamental transformations, though, have taken place in America’s once-industrial cities: a demographic transformation, largely driven by millennial in-migration; and an economic transformation from manufacturing to a new economy based on higher education and health care, the so-called eds and meds sector. In the next two chapters we will see how both are fueled by a unique juxtaposition of national change and embedded local assets, which, at least in some cities, had been there all along.