Max’s Taphouse on South Broadway in Baltimore’s Fells Point neighborhood is a local landmark. It claims “Maryland’s largest selection of draught beers, 103 rotating taps, five cask beer engines, more than 1,200 bottled beers, as well as amazing food.”1 It is only one of over a hundred restaurants, taverns, and nightspots in this historic neighborhood east of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor to which thousands of people throng nightly, eating, drinking, and simply hanging out on the cobblestoned streets and along the nearby waterfront. Off Broadway and Thames Street, the neighborhood’s two principal streets, the side streets glisten with beautifully restored row houses, where a tiny two-bedroom row house with a postage-stamp backyard on a narrow, treeless alley was recently listed for $375,000.2 Not long before writing this, I was talking to a friend, now in her sixties, who’d been born in Fells Point. When she was a little girl in the 1960s, the family moved out because “it had become too dangerous,” her father told her. Today, almost half of Fells Point’s population is between twenty-five and thirty-four years old.

Every large city in America can tell a similar story. At the dawn of the twentieth century, Washington Avenue was St. Louis’s garment district, lined with block after block of majestic five- and six-story buildings where people made clothing, shoes, and hats for the entire Midwest. After World War II, these factories began to close, and by the 1980s the avenue was all but deserted. Today, much like Fells Point, it is packed with bars, cantinas, hookah parlors, and more, drawing not only the thousands who live in the lofts and apartments that have been carved out of the old garment factories but still more thousands from all over the city and the region. Some call it St. Louis’s loft district, others its entertainment district, but either way, it has come vividly back to life.

Areas like Fells Point and Washington Avenue are just the most visible face of the astonishing transformations that are taking place in America’s cities. Neighborhoods are changing—often faster than their residents, neighborhood associations, or city governments can deal with. While Fells Point may be a playground for affluent millennials, only a little more than a mile east lies Highlandtown, a neighborhood being remade by Latino immigrants. Much the same thing is happening in Southwest Detroit in an area known as Mexicantown, where Mexican immigrants have transformed a stretch of that gritty city’s landscape to a place where thousands come from throughout the region for the neighborhood’s restaurants and stores. A community leader I spoke to had a simple explanation: “We’re all from Jalisco,” he said, “and people from Jalisco are Mexico’s entrepreneurs.”

This is not the whole story, of course. The neighborhoods that are being transformed in this way are only part, and often a small part, of Detroit, Baltimore, or St. Louis. Walk not too many blocks north of Washington Avenue, and you find yourself in an utterly different world, a lunar landscape of scattered houses, many of them empty, acres of vacant land where houses, long-since demolished, once stood, including the site of the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing project, now gradually reverting to woodlands like those that covered the site before the first French settlers arrived in 1765. Other neighborhoods in St. Louis or Baltimore that still look and feel like respectable neighborhoods are falling apart, hit by foreclosures, poverty, and rising crime, as vacant, abandoned houses—once unthinkable—start to appear on streets with well-maintained homes and front yards.

The transformation of America’s urban neighborhoods, like any major social phenomenon, is being driven by many different forces. Perhaps the most significant, though, are the changes to the makeup of America’s population and where and how people want to live. We are a very different country from what we were in the 1960s, when the decline of the cities became part of the national consciousness; we are even a very different country from what we were as recently as the end of the last millennium. To understand what is happening in our cities, we need to understand how we have changed as a nation over these years.

It is hard to believe how different the United States was in 1960 compared to what it is today. Two-thirds of all the houses and apartments in the country had a married couple living in them, and most of those couples were raising children. If you were a child, you were almost certain to be living with both of your parents; over 90 percent of all the households with children in the United States were headed by married couples. If you weren’t in a married couple, you were probably a single person living by yourself in an apartment, a rental room, or a single-room-occupancy hotel. Eighty-nine percent of the population were classified as “white,” and barely 5 percent of the country’s population had been born outside the United States. There were so few Latino immigrants from countries other than Mexico that the Census Bureau didn’t even bother to distinguish them by country, lumping them into a single “Other Americas” category.

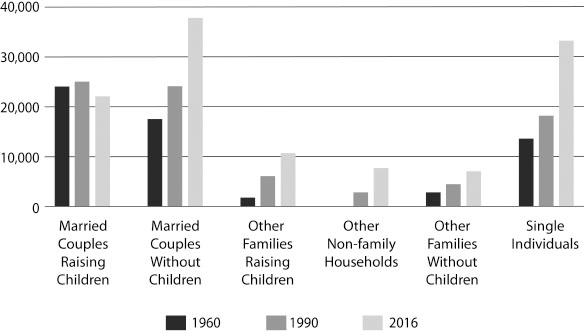

As figure 2-1 shows, the picture today is very different. Although the number of households in the United States has doubled since 1960, the number of married couples with children has actually gone down; there are 2.4 million fewer such families in the United States today than in 1990, and they make up only 19 percent of American households, and a much, much smaller share of urban households—only 9 percent of Pittsburgh’s and 7 percent of Cleveland’s households. One-third of childrearing families are single-parent families, mostly headed by women. The number of people living by themselves has increased by nearly 20 million, and there are 7.5 million “non-family households,” which includes people sharing homes, straight and gay unmarried couples, and the like, a category that didn’t even exist in the 1960 Census. Our foreign-born population has gone from less than 10 million to 42 million people, of whom half are from Latin America. The “non-Latino white” population share has steadily declined, and today makes up only 64 percent of the nation’s population.

Figure 2-1 Change in the number of households by household type 1960 to 2015. (Source: US Census Bureau)

In 1960, despite the G.I. Bill and the growth of higher education, there were only 2.5 million people aged twenty-five to thirty-four with four years of college under their belts, or about 1.5 percent of the population. By 2014, their numbers—members of the millennial generation, born between 1980 and 1990—had increased to 14.5 million, or about 4.5 percent of the United States population.

At the same time, the middle class has steadily shrunk, or, as some writers have put it, has been “hollowed out.” If we define middle-income households as those earning between 75 percent and 150 percent of the national median income—which translates roughly to $40,000 to $80,000 today—their share of all American households has dropped from 43 percent in 1970 to 25 percent in 2014. We have many more affluent households, most of them headed by people with college degrees, and far more struggling, lower-income households, most with less formal education. While, fifty years ago, having a college degree gave young people a modest 24 percent boost in income compared to their high-school-graduate peers, the gap has widened to 72 percent today, as more and more of the good, well-paying jobs for people without college degrees have dried up.3 Even though some people may not think so, having a college degree matters a lot in twenty-first-century America. Having a college degree may not be a ticket to success, but success is almost impossible today without one.

Paralleling the loss of millions of middle-class households is a related phenomenon which researchers have dubbed “economic sorting” or the growing tendency of people to sort themselves economically. In other words, there used to be a lot more neighborhoods where low-, middle-, and upper-income families were mixed together; today there are a lot fewer of those, and more and more that are either mainly poor or mainly affluent. Scholars Sean Reardon and Kendra Bischoff have studied this trend in detail; looking at 117 large and medium-sized metropolitan areas, they found that between 1970 and 2009, the percentage of families living in “middle-income” neighborhoods, where the neighborhood median income was 80 to 125 percent of the metro median, dropped from 65 percent to 44 percent. The number of families living in “poor” neighborhoods, where the neighborhood median income was two-thirds or less of the metro median, more than doubled, growing from 8 to 17 percent.4

All of this is very interesting, to be sure, especially for numbers wonks like me, but what does it mean for the cities? Each of the factors I’ve mentioned has a major impact on the trends in American cities. Let’s start with the people who fill Max’s Taphouse and its equivalents in other American cities every weekend.

It’s become something of a cliché to say that the millennial generation is flocking to the cities, but it’s true just the same. It’s been written about enough that some writers have tried to debunk the idea, but they miss the point; it’s not all millennials that are drawn to cities, just the roughly one-third of them with the college degrees, the tech skills, the earning power, and the yen for an urban environment—or a really cool taproom. They are changing the cities in ways small and large. I call them the Young Grads.

It’s not as if young people haven’t been drawn to cities before; the story of the young person who leaves his village to seek fame and fortune in the big city goes back hundreds if not thousands of years. Even as American cities declined after World War II, there has always been some contrary motion. A book entitled Back to the City, published in 1980, described the 1970s trend of “young, middle-class professionals … buying homes in those lower-income urban neighborhoods that contain structurally sound or attractive housing.”5 I know a lot about this trend because I was part of it, a newly remarried thirty-something professional who bought a barely habitable row house in Philadelphia’s then-borderline Fairmount neighborhood in the late 1970s.

We were “urban pioneers,” a term that suggests both how exciting the phenomenon was in some respects, but also how marginal it was in others. We plugged into a network of like-minded pioneers, through whom we found out which plumbers were reliable and which were not, learned about the man who refinished floors and made a paste out of the sawdust to fill the cracks, and met the man who rebuilt our marble fireplaces so beautifully that one would never guess that, when we bought the house, we found the smashed fragments in a cardboard box. We had to drive five miles to the suburbs to buy groceries, but we had Fairmount Park on our doorstep, and lots of hot new restaurants in Center City like the Commissary and Astral Plane.

In retrospect, though, the effects of the “back to the city” movement of the 1970s and 1980s were quite modest; outside of a handful of outlier cities like Boston, it had little effect on American cities’ overall trajectory. Here and there an urban neighborhood was dramatically transformed or gentrified—a term that came into vogue during the 1970s—and stayed that way. Spring Garden, which was closer to Center City than Fairmount, and had truly magnificent houses, became an upscale neighborhood during those years, and has never looked back. Many more, including Fairmount, languished for decades.

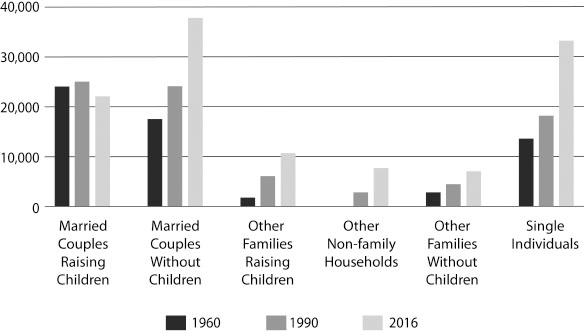

For most cities, the urban pioneering of the 1970s was a blip, not a trend. The house we bought in the late seventies steadily lost value relative to inflation over the next twenty years. By then we’d moved and rented the house out. Around 2000, Fairmount started to change rapidly; the value of our house more than doubled from 2000 to 2003, and we sold, to a young single lawyer. By that point, moving to the city was no longer a quirk of a small atypical minority. It had become a normal thing, a pattern that began in magnet cities like Seattle or Washington, DC, and then spread to the legacy cities. Every year since 2010, 4,000 or more Young Grads have moved into Baltimore, and 3,000 or more into Pittsburgh. By 2014, more than one in nine Pittsburghers were Young Grads, nearly three times the national average. As figure 2-2 shows, this is a growing trend—little or nothing in the 1990s, a lot more in the 2000s, and still more since 2010.

Figure 2-2 The Young Grads move to the cities: average annual increase in college-educated population, ages 25–34. (Source: US Census Bureau)

What is going on? In a nutshell, the pull of urban living for today’s educated young people is far greater than at any time in the recent past. To understand why, we must look both at the cities and at the Young Grads themselves. America’s legacy cities have changed a lot since they were gritty centers of industry. As urban economies have shifted from manufacturing toward health care and higher education, they have also become, in sociologist Terry Nichols Clark’s phrase, “entertainment machines.”6 We will discuss this phenomenon in detail in the next chapter.

Another important factor is that cities in the last twenty years have become much safer places. Most of America’s older cities were fairly dangerous places in the 1990s, only to see crime drop sharply over the ensuing decades. New York City’s story is famous, but many other cities saw similar trends; between 1995 and 2005, the FBI crime index—a composite of the most serious violent and property crimes—dropped by a quarter in St. Louis and Philadelphia, and by over 50 percent in Baltimore and Washington. Not only are cities, or at least those parts where Young Grads gather, safer, but the word has gotten out: people with no particular sensitivity to the nuances of urban life feel safer in cities. While in the 1990s many people were wary of walking through Washington’s DuPont Circle after dark, ten years later it had become a millennial playground, thronged with young people comfortably hanging out well into the night.

When we look at the recent Young Grad in-migration, it is impossible to tell precisely how much credit is due to the ways the cities have changed, and how much to the ways attitudes and preferences have changed from one generation to the next. There’s compelling evidence, however, that both play a part. The generation that has reached adulthood in the last ten or fifteen years does seem to have a different attitude toward cities and urban living than its predecessors. A host of recent surveys have found that people in their twenties and thirties are more likely to prefer cities as a place to live, would like to do without a car, and tend to seek out places with diverse people and cultures; as one 2016 study put it: “‘Location, location, location’ for this generation means being close to an urban core so that millennials can easily get to work, amenities, and transit. Studies show a new fondness for living near service amenities like music venues, theaters, bars, gyms, etc.”7 Not only are there far more Young Grads than ever before, but they are deferring marriage and childrearing longer than previous generations, which means that more of them are single or in the sort of informal relationships that go well with being part of a lively urban social scene.

Some media pundits would have one believe that the urban revival is just as much about empty-nesters and retiring baby boomers as it is about millennials, but the numbers don’t bear them out. It’s not completely untrue. The number of well-educated, affluent empty-nesters and baby boomers living in the cities is growing. But that growth has to be seen in proportion. Their numbers are growing less because boomers and empty-nesters are flocking to the cities, than because their numbers are increasing so fast overall—their numbers are rising almost everywhere.

Starting in the 1960s, a lot more people in the United States began going to college. As a result, between 2000 and 2014, the number of people over sixty-five with college degrees in the United States more than doubled, as the big cohort of 1960s and 1970s college graduates moved through their life cycle. Their numbers increased almost everywhere. The fact is, though, that relative to that age group’s growth in the population as a whole, older American cities—even the most successful in terms of drawing Young Grads—are still lagging.

Washington, DC, is seeing an influx of college graduates in their late thirties and early forties along with the younger people who have changed the character of that city. So is Baltimore, although to a lesser extent. Both cases may be in part an echo effect from the migration of Young Grads in the previous decade, but may also reflect a greater readiness of some affluent, well-educated people to stay and raise their family in the city. Neither of these cities, though, are seeing as much growth among older adults. Yes, there are empty-nesters and baby boomers who are moving to the cities, but their numbers are still modest compared to those who are moving elsewhere, or simply staying put. They are contributing to urban revival, but not driving it.

The second big demographic change in cities, though, is not about growth, but about decline—specifically, the loss of the population that historically defined the American middle class and the American urban neighborhood: the childrearing married couple. In our postmodern era of fluid roles and personal reinvention, such families, with their Leave It to Beaver overtones of husbands off to work in the morning toting lunch pails or briefcases and wives staying home to raise the children and cook hearty, filling family dinners, seem uncomfortably anachronistic.

That way of life may be gone forever, and many people may see that as a good thing, yet as is often the case with major social changes, the unintended consequences, particularly for America’s industrial cities, are far from benign. In this case, the consequences have had to do with the kinds of places the neighborhoods of legacy cities actually are. Rather than being made up of blocks of tenements familiar from images of Manhattan, the traditional, early-twentieth-century urban neighborhood in the United States was a neighborhood of single-family homes, designed and built for the sole purpose of accommodating married couples, those raising children, those planning to do so, or those who had finally seen the last of their brood leave the home. These neighborhoods still exist as physical spaces, but as I will discuss in detail in chapter 6, as the pool of childrearing married couples has declined—and as we’ll see, all but disappeared in many cities—they have lost the function for which they were built, with, at least so far, nothing comparable to take its place.

Let’s look at two of Ohio’s smaller industrial cities, Akron and Youngstown. These were hard-core industrial cities. Akron was called “the rubber capital of the world,” and in the early twentieth century was the home of Goodrich, Goodyear, Firestone, and General Tire. Steelmaking was to Youngstown what rubber tires were to Akron. In 1960, nearly half of the workers in each city worked in the factories, and most of the rest supplied groceries, health care, and government services to the factory workers. More than two-thirds of all the households and 90 percent of all the families in both cities were married couples. Over half of those couples were raising children under eighteen.

Today, most of the factories in both cities have closed, and most of the manufacturing jobs have disappeared. Instead of 24,000 factory workers as in 1960, only 2,800 live in Youngstown today. But the number of married couples raising children has dropped even faster. Less than a quarter of the households in Youngstown are married couples—a bit more in Akron—and only a quarter of them, or less than 5 percent of all households, have children in the home. From 21,000 married couples with children in 1960, there are only 1,000 today. More than two out of every five households in both cities is a single person living alone. Even though Youngstown has only half as many households today than it had in 1960, it has the same number of single people as it did then.

There are many reasons why childrearing married couples, of all races and ethnicities, who are the epitome of the American middle class, continue to leave the cities. The racially driven white flight of the 1960s and 1970s may be a thing of the past, but middle-class flight, made up of as many if not more black than white families today, continues. They are frustrated by the continuing challenge of ensuring that their children can get a good education, and by the pervasive presence of crime in their lives—not so much the murderous violence that continues to devastate the cities’ most distressed neighborhoods, but what one might call the constant pinpricks of urban life: the break-ins, the petty vandalism, the graffiti on the walls. They are worn down by the high property taxes and the poor public services, and the fact that it may take hours for the police to show up and the streets are potholed and many of the streetlights broken. As Ray Suarez writes, fatigue sets in: “The strain of having eyes in the back of your head, higher insurance, rotten local services, and the day-upon-day-upon-day of bad news finally carries you across a line….”8 Above all, they leave because they can. With two wage earners in most married-couple families today, they have lots of options in the city’s suburbs.

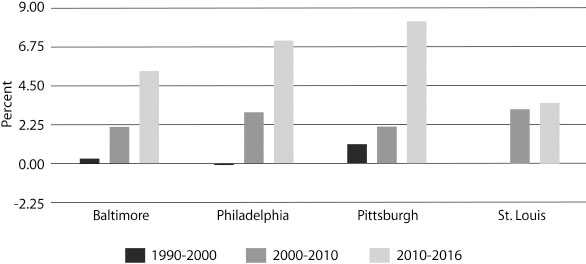

The upshot is that the number of kids in cities has steadily dropped, and the number of kids in married-couple families has dropped even faster. There is no evidence that the long-term trends have begun to shift. While I hear stories in my travels about how a particular charter school has drawn families with school-age children back to urban neighborhoods here or there, as with the City Garden Montessori school in St. Louis, the data tells me that these situations are outliers in a larger trend of continued decline. As figure 2-3 shows, while a few cities have seen an increase in the number of preschool children in married-couple families since 2000, they have all seen precipitous declines in the number of school-age children in married-couple families, beginning at the age of six. St. Louis and Philadelphia are seeing more infants and toddlers, and in Baltimore, the number of three- to five-year-old children is also on the increase, but at that point the drop-off begins. Moreover, in none of these cities is there much difference between the trends for the elementary and those for middle- / high-school age groups.

Figure 2-3 Change in the number of children in married-couple families by age group, 2000–2015. (Source: US Census Bureau)

As these families leave, the demand for the cities’ single-family neighborhoods declines. The aspiring Young Grads want to live in downtowns and high-density neighborhoods around universities, and few want to buy tired, turn-of-the-century, frame houses or small fifties bungalows in outlying areas far from the scene and the action. As the number of married couples with children has declined, the number of single women raising children has gone up—although by a far smaller number—but with few exceptions they are far poorer than the families they replaced, and have a far harder time making ends meet, let alone maintaining the old houses that are wearing out around them. They are far less likely to be able to buy their home, and except for the fortunate few who win the housing voucher lottery and obtain a rent subsidy, chronic income insecurity puts them constantly at the mercy of their landlords.

As we’ll see in chapter 6, there are a lot of other reasons why many urban single-family neighborhoods are declining, while the same city’s downtown and other areas populated by Young Grads are booming. But it all starts with the demographic changes taking place in the United States, and particularly in the country’s older industrial cities.

There’s another demographic story, though, that offers an important and hopeful counter-trend and is increasingly being seen in America’s legacy cities. That story is immigration. Detroit’s Conant Street is a long, gritty street that starts just north of General Motors’ Detroit-Hamtramck Assembly plant, and runs north by northwest to the Detroit city line at Eight Mile Road. As you drive north on Conant, first through Hamtramck—a small city completely surrounded by Detroit—and then through Detroit itself, you see store signs first in Arabic and then more and more in Bengali, the language spoken in Bangladesh. A little north of Caniff Street, where one side of Conant is in Detroit and the other in Hamtramck, the stores cluster more closely together. Al-Hishaam Islamic Gifts and Indian Fashion is quickly followed by Amar Pizza, Islamic Bargain (“Clothing, Oils, Jewelry, and More”), Universal Multiservices (tax, travel, and immigration services), Bengal Spices, Aladdin Sweets & Café, Al-Amin Supermarket, Zamzam Bangladeshi, Indian and Pakistani Cuisine, Shah Puran Grocery & Halal Meat, and on and on.

You are in Banglatown, a neighborhood half in Hamtramck and half in Detroit. Steve Tobocman, founder of Global Detroit, tells me that half of the residents are foreign-born; half of those are from Bangladesh, and about half of the rest are from Yemen. Global Detroit has partnered with the Bangladeshi American Public Affairs Committee to help build the business community and ultimately make it a regional visitor destination. As Ehsan Taqbeem, founder of the Committee, says, “[in Detroit] we have Mexicantown, we have Greektown”—citing the city’s better-known immigrant neighborhoods and restaurant destinations. “So, let’s have Banglatown.”9

Banglatown may or may not ever become a visitor destination. It isn’t pretty or picturesque. Conant Street will never be a historic district. The buildings that house the stores are basic, undistinguished, and often tired properties. They are interspersed with parking lots, used-car dealers, and gas stations on a street where the only greenery in sight are the weeds coming up through the cracks in the curbs and sidewalks. But it is vibrant and full of life, and the housing vacancy rate in the blocks of neatly tended bungalows on either side of Conant Street is only 2 percent, compared to over 22 percent in the rest of Detroit.

Banglatown is not unique. Across the city, Mexican immigrants have revived much of the Southwest Detroit neighborhood. Cambodians and Vietnamese have brought new life into fraying parts of South Philadelphia. Cherokee Street west of Jefferson Street in St. Louis has become a vibrant Latino shopping street. Newark’s Ironbound neighborhood, its name supposedly coming from the railroad tracks that once ringed the neighborhood, became a heavily Portuguese immigrant neighborhood in the 1950s. Although many of the children of those immigrants have since moved to the suburbs, they created a Portuguese-language infrastructure of stores, sports clubs, restaurants, cafes, doctors, and lawyers that not only draws visitors from all over the New York metropolitan area, but has also drawn a second wave of Portuguese-speaking immigrants from Brazil and the Cape Verde Islands, along with other Latin American immigrants. The Ironbound is Newark’s most vital neighborhood, and Ferry Street, its main thoroughfare, Newark’s liveliest shopping street.

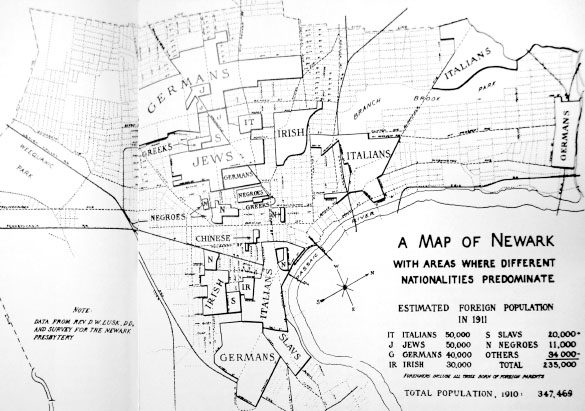

In many respects, this is nothing new. Ethnic neighborhoods are the matrix from which much of modern American society emerged. A hundred years ago, the neighborhoods of America’s industrial cities were largely ethnic enclaves, often dominated by a single ethnic group. A 1911 ethnic map of Newark delineated the “areas where different nationalities predominate,” showing large zones of German, Italian, and Jewish concentration, along with smaller pockets of Irish, Negroes, Greeks, Slavs, and Chinese (fig. 2-4). While the Newark map shows the heaviest concentrations of Germans, Italians, and Jews (and simply refers to “Slavs” generically, reflecting their modest role in the city’s ethnic jigsaw puzzle), a Cleveland map from the same era distinguishes among Polish, Czech, Ukrainian, Slovak, Slovenian, Serbian, and Croatian ethnicities, large communities in their own neighborhoods, and smaller ones in multiethnic clusters.10

Figure 2-4 Mapping ethnicity: Newark in 1911. (Source: Littman Architecture and Design Library, New Jersey Institute of Technology)

Although a handful of exceptions like The Hill, an Italian neighborhood in St. Louis, or the still largely Jewish neighborhood of Squirrel Hill in Pittsburgh hang on, the European ethnic enclaves of the cities’ industrial heyday have almost entirely disappeared, done in by assimilation, prosperity, generational change, suburban flight, and in particular by the lack of new immigrants from those countries to replace those passing away or fleeing to the suburbs. Places like Banglatown, Mexicantown, or the Cambodian pocket in South Philadelphia are in many respects the twenty-first-century counterpart of the early twentieth-century ethnic enclave, places where new immigrants can find a community of people who share their language and culture while figuring out how to fit into a new, often daunting country.

Will the new ethnic neighborhoods last? Cities are constantly in flux, and neighborhoods constantly change. Detroit had a flourishing Chaldean Town made up of Christian immigrants from Iraq in the 1970s, but it disappeared, victim of the push of rising crime and the pull of suburbanization.11 The Ironbound, on the other hand, is going strong well into its third generation as a largely Portuguese-speaking but increasingly also Spanish-speaking enclave. One can never tell about any one neighborhood, but as long as the United States continues to welcome large numbers of immigrants, immigrant communities are likely to form in places where the opportunity exists to settle, find affordable housing, and find a job or open a business. Some will disappear as their residents blend into the American mainstream, but new ones will emerge. Some will struggle, but others may thrive.

Up to now, though, America’s legacy cities have lagged as immigrant destinations. No older industrial city has the rich mosaic of ethnic immigrant neighborhoods that give New York City or Los Angeles, or for that matter Houston, so much of their propulsive energy. None of the older industrial cities has a foreign-born population share equal to the national level, and immigrant enclaves like Banglatown or Cambodian South Philadelphia are still only small pockets within their city’s larger fabric.

This may be changing, though. Between 2000 and 2015, the foreign-born population nearly doubled in Baltimore, and grew by nearly 50 percent in Philadelphia and in Pittsburgh. This is still a far cry from a hundred years ago, when nearly two-thirds of Pittsburgh’s population and fully three-quarters of Cleveland’s were either foreign-born or the children of immigrants. Still, it is another sign that things are changing in America’s older industrial cities.