The multidimensional, conflicted, and stressful relationship between white and black in America is the inescapable presence, the unavoidable elephant in the room of American society. It is nowhere more so than in the nation’s legacy cities. Over fifty years ago, in his powerful book Crisis in Black and White, Charles Silberman wrote that “solving the problem of race is not only the most urgent piece of public business facing the United States today; it is also the most difficult.”1 Soon thereafter, in the wake of the riots that convulsed American cities in the 1960s, the Commission on Civil Disorders appointed by President Johnson began its 600-page report with the warning that “our nation is moving toward two societies, one white, one black—separate and unequal.”2 The commission concluded that the present course of action “would lead to the permanent establishment of two societies, one predominately white and located in the suburbs, in smaller cities, and in outlying areas, and one largely Negro located in central cities.”3 Although their prediction that the line would run neatly between cities and suburbs has not stood the test of time, their underlying conclusion is no less true today than it was fifty years ago.

To understand how race, real estate, and revitalization are so intertwined, though, one has to go much further back. As small numbers of African Americans trickled into northern industrial cities toward the end of the nineteenth century and early in the twentieth, they were not welcomed warmly. While efforts to keep blacks out of large parts of the cities, or to keep them from competing for valued factory jobs, were informal, they were often enforced with violence. In 1910, after local black lawyer George McMechen and his wife moved into a row house at 1834 McCulloh Street in what was then a white neighborhood, Baltimore decided it was time to give racial segregation the force of law. The city enacted an ordinance specifying that “no negro may take up his residence in a block within the city limits of Baltimore wherein more than half the residents are white.”4 In the grand tradition of forbidding rich as well as poor from sleeping under bridges, the ordinance also barred whites from living in predominately black blocks.

Baltimore’s mayor justified this step, arguing that “Blacks should be quarantined in isolated slums in order to reduce the incidents of civil disturbance, to prevent the spread of communicable disease into the nearby White neighborhoods, and to protect property values among the White majority.”5 In a decision unusual for its time, the Supreme Court struck down Baltimore’s ordinance in 1917; hostility to black families looking for better housing, however, grew along with the rapid growth in urban black populations during and after the First World War.

During the 1920s, conflicts erupted in many cities, including Detroit. Legal scholar Douglas Linder describes the events there in 1925:

In April, 5,000 people crowded in front of a home on Northfield Avenue, throwing rocks and threatening to burn the house down. “The house is being rented by blacks,” someone in the crowd explained to police arriving at the scene. […] The next month, John Fletcher and his family were the targets of mob violence. The Fletchers had just sat down to a meal in their new home on Stoepel Avenue when they were spotted through a window by a passing white woman. The woman began to yell, “Niggers live there! Niggers live there!” Soon a crowd of 4,000 had gathered. Some in the crowd yelled, “Lynch them!” Chunks of coke smashed through windows.6

The Fletchers moved out the next day. That fall, though, a black doctor named Ossian Sweet moved with his family into a house on Garland Street, in a then-white neighborhood of the city. Although the first night passed without event, the next night a mob gathered around the house, shouting, “Niggers, niggers, get the damn niggers!” A fusillade of rocks hit the house, smashing windows. Fearing that the mob would soon invade the house and lynch them, someone inside fired into the crowd from the second-floor window, killing one man and wounding another. Sweet and his family members, all of whom had been arrested after the shooting, were tried and found not guilty, thanks to a brilliant defense by Clarence Darrow. A historic marker commemorating the episode stands alongside the house today (fig. 4-1).

Figure 4-1 Dr. Ossian Sweet’s house on Garland Street. (Note historical marker at left.) (Source: Google Earth)

Although Dr. Sweet moved back into the Garland Street house not long after the trial and lived there until 1948, his story and others like it, rather than opening doors for others, led to redoubled efforts to maintain segregation in northern cities. With local ordinances no longer permitting overt segregation, the preferred tool became the racial covenant, a legal provision in the deed of sale typically barring the buyer from selling or renting the house to “any person or persons not of the white or Caucasian race,” often barring Jews or other ethnic groups as well. The use of such covenants grew through the 1920s and 1930s until they were struck down by the Supreme Court in 1948. Between 1921 and 1935, 67 out of 101 new subdivisions filed in the city of Columbus, Ohio, included racial covenants.7 Even the University of Chicago’s famously liberal president of the time, Robert Maynard Hutchins, defended the local use of racial covenants “to stabilize its neighborhood as an area in which its students and faculty will be content to live.”8

The effect of racial covenants was compounded by redlining, which emerged in the 1930s with the creation of “residential security” maps of each city’s more or less desirable neighborhoods, most famously by the federal government’s Home Owner’s Loan Corporation to demarcate the areas where the HOLC would provide federally backed loans to refinance mortgages on homes threatened with foreclosure. While the extent to which the maps affected the HOLC’s activities is still debated, with some arguing that they did little more than ratify existing practices, they firmly put the federal government’s stamp on racial discrimination by rating most black neighborhoods with a D, or unsuitable for lending.

Whether or not the Federal Housing Administration, which was created in the New Deal to open up home-buying to working- and middle-class American families, actually used the HOLC maps is unclear; what is clear is that the FHA’s lending practices strongly encouraged racial segregation long after the Supreme Court had voided racial covenants and well into the 1960s, even after President Kennedy’s 1962 executive order calling for “the abandonment of discriminatory practices with respect to residential property and related facilities heretofore provided with federal financial assistance.”

What makes the intensity with which whites defended the color line in the 1920s and 1930s even more striking is that the black populations of most cities were still quite small compared to what they would become after World War II. In 1925, when Ossian Sweet and his family went on trial, African Americans made up only 6 percent of Detroit’s population; in 1940, less than 10 percent of Cleveland’s residents were African American. The growth of these cities’ black population during the first Great Migration of the 1910s and 1920s, however, had been rapid; the black population of Detroit went from 6,000 in 1910 to 41,000 in 1920 and 120,000 by the eve of the Great Depression. Detroit’s white population was also growing rapidly during the same years, though, going from less than half a million in 1910 to nearly 1.5 million by 1930.

As African Americans moved to the cities in search of better living conditions and greater opportunity, they encountered many barriers to achieving either goal. Black workers seeking factory jobs came up against intense resistance from white workers; even as World War II raged, thousands of white workers walked off the job at the Detroit Packard plant, which made engines for PT boats and bombers, when the management promoted three African American workmen. White clerical workers at Hudson’s, Detroit’s flagship downtown department store, walked off the job when the company began to hire black women to work alongside them.9 With few neighborhoods open to them, blacks moving to Detroit mostly squeezed into the Black Bottom area east of downtown, along with a few smaller pockets elsewhere in the city.

Black Bottom, which was named after its rich black soil long before the first African Americans arrived, had been an immigrant neighborhood since the mid-nineteenth century, where Germans, Poles, Jews, and Italians had each lived briefly and moved on. Discrimination, however, prevented the African Americans who began to move into Black Bottom in the early twentieth century from similarly moving on. By mid-century, this small area was home to over 140,000 people. It had become increasingly a dilapidated, dangerously overcrowded neighborhood made up of rickety wooden structures, most built before 1900. Many lacked indoor plumbing, and their residents depended on the 3,500 latrines that dotted the neighborhood.10 Few owned their own homes, and nearly all were at the mercy of the landlords who owned all but a handful of the neighborhood’s houses and apartments.

At the same time, it was a dynamic, vibrant community with a strong commercial core along Hastings Street and a thriving music scene, particularly in the northern part of the area known as Paradise Valley. As Detroiter Elaine Moon wrote, “It was the black downtown, Broadway, Las Vegas. A place of fun, brotherhood, and games of chance. A place known from here to Europe. In the 1930s and early ’40s in Detroit, a night on the town, for Black or White, was not complete without a stop at Paradise Valley.”11

Bad as things were by the end of World War II, though, in many respects they were to get worse. The fifties and sixties not only saw millions of African Americans flock to the nation’s industrial cities, but they were also the era of urban renewal and the Interstate Highway program. While neighborhoods of all descriptions, along with large parts of most cities’ downtowns, fell to the wrecking ball, black neighborhoods, particularly those strategically close to downtown, were often singled out for removal. Black Bottom was quite literally obliterated. Most of it, including Hastings Street, was buried under the Chrysler Freeway (I-75), while much of the rest was razed to build the upscale Lafayette Park development, three apartment towers and 186 townhouses in a landscaped, self-contained nineteen-acre “superblock” designed by famed Bauhaus architect Mies van der Rohe. While Lafayette Park is now on the National Register of Historic Places, its construction was made possible by the displacement of some 7,000 African Americans, most of whom moved elsewhere into homes little better than the ones they had been forced to leave.12

City after city tells a similar story. In Pittsburgh, much of the Lower Hill district, immortalized in August Wilson’s great cycle of plays, was razed to construct the Civic Arena, built in 1967 and demolished in 2011. As many as 8,000 residents were displaced and dispersed, some to public housing, some to other parts of the Hill, and others across the city of Pittsburgh and nearby mill towns. Mill Creek Valley, a run-down African American neighborhood in the shadow of downtown St. Louis, was demolished in 1959, displacing 20,000 residents; as one account put it, “The bulldozers swiftly transformed the city’s ‘No. 1 Eyesore’ into an area derided as ‘Hiroshima Flats.’”13 By 1960, only twenty original families still called Mill Creek home. Of the million or more American families displaced by both the interstate highway program and urban renewal, perhaps as many as half were black.

Part of this was driven by the same perverse logic that led engineers to route other highways through parks and along waterfronts. Land occupied by poor people cost less to acquire, and poor people had less ability to fight back. Unlike Jane Jacobs and her Greenwich Village neighbors, who successfully organized to block Robert Moses’ plan to run a highway through the area, few black communities had the political clout or organizational strength to keep the bulldozers out. But there was a darker side to the planners’ thinking, a pervasive association of slums with disease, not only in the narrow sense of their being seen as breeding grounds for diseases like tuberculosis or typhus, but as a disease in themselves; as noted Finnish-American architect Eliel Saarinen wrote in his influential 1943 book The City, “large areas in the heart of the city have become the centers of a contagious disease which threatens the whole organism.” After describing this in detail, he came to his point, printed in bold in the book for emphasis: “Urban conditions cannot be cured in [a] superficial manner. [The planner] must unearth the roots of the evil. He must amputate slums by a decisive surgery.”14 Over the next decades, the word slum was gradually replaced by ghetto, and the disease metaphor took on an increasingly racial character. That, too, must be seen as part of the climate that allowed local governments, corporations, and institutions to obliterate long-established black neighborhoods with such seeming indifference to the effect on their residents and businesses.

Meanwhile, the Second Great Migration of African Americans from the nation’s South to the North and West that began during World War II, an exodus that dwarfed the earlier migration, was well under way. Between 1941 and 1970, 5 million African Americans left the South for other parts of the country, with large numbers heading for northern industrial cities. From 1940 to 1970, Chicago’s black population went from 277,000 to 1.1 million, and that of Detroit from 149,000 to 660,000. By 1980, fully half of the black residents of both cities had been born in the South.

The response they received, though, although no warmer, was radically different from that which had greeted the first migration, and which had brought the neighborhood toughs out to throw stones at Dr. Sweet’s house. If the white response in the 1920s was to fight, in the 1950s and 1960s it was flight. Millions—over a million and a half from Chicago alone—fled the cities for their burgeoning suburbs or the booming cities of the Sunbelt, their flight often accelerated by the blockbusting and other unsavory tactics practiced by local realtors and speculators.

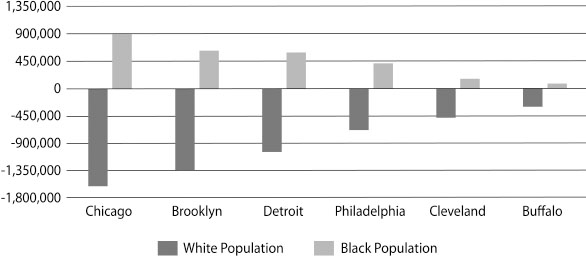

Many different factors contributed to white flight after World War II, but even after taking account of the enticements of affordable suburban houses and inexpensive mortgages, the new highways, and the shabby postwar condition of many cities after years of disinvestment, race stands out as the most powerful; UCLA economist Leah Boustan has calculated that “each black arrival was associated with 2.3 to 2.7 white departures,”15 as figure 4-2 shows. With white departures substantially outnumbering black arrivals, America’s older cities began to shrink.

Figure 4-2 Change in white and African American populations of selected cities, 1940–1980. (Source: US Census)

White flight, coupled with the gradual effects of civil rights and fair housing laws, meant that thousands of African Americans were now able to move out of the crowded areas where they had largely been confined up to that point. From the 1960s through the 1980s, black families moved into large parts of American cities that were being abandoned by their longtime white residents.

This created new opportunities for many African Americans, but it also meant the end of the traditional black neighborhood. Created by segregation and rife with poverty, overcrowding, and substandard housing, they were neighborhoods with a vital energy, with their own stores, their own doctors and lawyers, where rich, poor, and middle-class lived side by side and mingled daily in the streets, the stores, and the churches. Looking back at the 1960s, African American columnist Eugene Robinson wrote in 2010, “no one quite realized it at the time, but Black America was being split.”

Those who could, moved; those who could not, stayed. Robinson sums up the change:

Some moved out—to neighborhoods unscarred by the riots, to the suburbs … and moved up, taking advantage of new opportunities. They moved up the ladder at work, purchased homes and built equity, sent their children to college, demanded and earned most of their rightful share of America’s bounty. They became the Mainstream majority. Some didn’t make it. They saw the row houses and apartment buildings where they lived sag from neglect; they hunkered down as big public housing projects … became increasingly dysfunctional and dangerous. They sent their children to low-performing schools that had already been forsaken by the brightest students and the pushiest parents. They remained while jobs left the neighborhood, as did capital, as did ambition, as did public order. They became the Abandoned.16

In 1970, the average African American lived in a neighborhood that was more economically mixed, with the well-to-do, middle-class, and poor living side by side, than the neighborhoods where most white people lived. Only a decade later, that was no longer true. As Bischoff and Reardon write, “segregation by income among black families … grew four times as much [as among white families] between 1970 and 2009.”17 They add that “although income segregation among blacks grew substantially in the 1970s and 1980s, it grew at an even faster rate from 2000 to 2009.” (We will look at the factors driving that change later in this chapter.)

The transformation Robinson describes could be subtitled “The Making of the Ghetto,” not only as a reality, but as a term that came into common use in the 1960s and 1970s to describe the distressed, poor African American neighborhoods that now seemed to be a fixture of every older city in America. How the word ghetto, a word coined in sixteenth-century Venice, became the code word for these neighborhoods is itself a useful object lesson in how words become racialized, and what that comes to mean.18

When the Venetian authorities forced the city’s Jews to move into a small walled compound in Cannaregio in 1516, that area came to be known as the Ghetto, a name whose origins are still obscure. The word caught on, appearing in the papal bull that created the Rome ghetto in 1562. During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in city after city Jews across Western Europe were confined to ghettos, most famously perhaps in Rome, where in addition to being segregated, Jews were regularly herded into churches to be forced to listen to sermons exhorting them to convert to Christianity and taxed to pay for the priests giving the sermons.

With the coming of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century, the ghettos were gradually abolished. The last one to be dismantled was in Rome, with the end of papal rule in 1870. The ghetto was revived in far more horrific fashion in the twentieth century by Nazi Germany, which herded Jews into closed zones in Eastern European cities, either to exploit their labor or to confine them to interim holding camps pending their murder by the Nazi killing machine.

During the first half of the twentieth century, before the word ghetto took on its association with the Holocaust, it was applied loosely in the United States to racial and ethnic enclaves of all sorts, but particularly to Jewish immigrant communities. A popular book of 1902, Hutchins Hapgood’s The Spirit of the Ghetto, about the Jewish Lower East Side of Manhattan, described the “intense and varied life [of] the colony of Russian and Galician Jews who live on the east side and form the largest Jewish city in the world.”19 During World War II, though, spurred by the awareness of what was going on in Eastern Europe, people in the United States began to focus on the black or “Negro” ghetto, making the point that—in contrast to the white ethnic “ghettos”—urban blacks who tried to move out “hit the invisible barbed-wire fence of restrictive covenants.”20

Whether or not St. Clair Drake and Horace Clayton, the two black sociologists who wrote those lines in their magisterial work Black Metropolis in 1945, were deliberately drawing an analogy with the barbed wire the Nazis used to build their ghettos is unclear, although it is hard to imagine that it was not on their minds. As with Kenneth Clark, who published Dark Ghetto twenty years later, it was largely African Americans, both scholars and advocates, who used the term ghetto to call attention to the fact that, unlike white ethnic groups that initially clustered together for mutual support and cultural solidarity and for the most part moved onward as they assimilated and prospered, black people were kept hemmed in by the outside white world.

As Robinson’s “Mainstream majority” began to move out of the traditional black neighborhoods in the 1960s and 1970s, the idea of what a ghetto meant was transformed once again. Now, it was no longer an area defined by race, but by race and class. It was no longer clearly hemmed in by explicit, formal barriers, but by more subtle, if equally powerful, barriers of social pressure and poverty; as Dutch scholar Talja Blokland puts it, it became the “spatial expression of social processes.”21 The term inner city, which came into use in the 1960s and 1970s, came to be seen as almost a synonym. Despite its literal meaning, though, inner city is not a geographic term; as Brooklyn blogger Justin Charity writes, it can be anywhere: inner city “is a uniquely American term. In its common usage, it signifies poor, black, urban neighborhoods. The term somehow applies regardless of whether [or not] such neighborhoods are downtown or central to the city grid.”22

Both terms, especially as used by the larger society to stigmatize the people it has left behind, are sometimes resented, but they have also become a trademark for many young African Americans who have come to use ghetto and inner city to stand for a distinct, oppositional strand of African American culture that challenges white mainstream culture. Leaving culture aside, though, the terms reflect a physical reality: the presence of large areas of concentrated, persistent, and largely African American poverty in almost every older city in the United States. These areas are as distinct and important a type of urban neighborhood as the gentrifying areas or the middle neighborhoods we will explore in the following chapters. Whatever one’s feelings toward these terms, whether used by white politicians or black rappers, these are the places people are thinking about when they say ghetto or inner city. They are real.

Putting the words concentrated poverty and African American together in the same sentence is not accidental. While there are many poor white families in the United States, many of whom live in urban areas, few live in urban areas of concentrated poverty. In Baltimore, half of all poor African Americans live in areas of concentrated poverty, compared to only one out of five poor whites. In Milwaukee, over 70 percent of poor blacks live in high-poverty areas.

In contrast to the bustling, vibrant streets of the mid-century African American neighborhoods depicted by so many writers, though, the most powerful visual impression many longtime ghetto areas make today is one of sheer emptiness. Walking down Market Street in North City St. Louis, shown in figure 4-3, one sees block after block of vacant, derelict houses and vacant lots, mixed with scattered still-occupied homes and churches, occasionally interspersed with a low-income housing project or two. It hardly comes as a surprise to learn that this part of St. Louis, where nearly 37,000 people lived in 1970, houses only a little more than 6,000 today.23

Figure 4-3 North Market Street in North City St. Louis. (Source: Google Earth)

North City may be extreme, but it is not unique. The Kettering section of Detroit’s East Side housed 45,000 people in 1970, but only 9,000 today. Not surprisingly, a 2013 survey found that over half of the area’s houses have been torn down, with vacant lots left in their place, while over a quarter of the remaining houses are vacant and abandoned.

Detroit’s East Side and North City St. Louis may be further down the path of abandonment than equally distressed areas in some other cities, but the story is the same—a steady progression of decline that has gone on for decade after decade. As we showed earlier, far more white people fled the cities than African Americans came to take their place. Some American cities, like St. Louis and Pittsburgh, started to lose population in the 1950s, while the exodus turned into a flood in the 1960s and 1970s. As Robinson’s Mainstream majority moved out of the ghetto, the poor stayed behind.

Gradually, a vicious cycle emerged. As areas became increasingly poor and run-down, fewer and fewer people who could afford to live somewhere else wanted to stay. With more areas open to African American families, ghetto residents who got a promotion, a college degree, or a new, better, job, moved out. As fewer and fewer people wanted the houses, just as the law of supply and demand would predict, they were worth less and less, to the point where a house cost less than a good used car. Owners made fewer and fewer repairs—why bother when you’d never get your money back?—and the houses started to fall apart. A lot of owners stopped paying property taxes, and their properties started to wind up in the hands of city governments, which took them over even though they didn’t really want them and usually didn’t know what to do with them. Here and there, a developer or a nonprofit organization got federal money and put up a low-income housing project. That meant that a few poor people had better housing, but it did nothing to change the area’s downward spiral.

Soon, the only people buying houses in these areas were absentee owners, usually short-term speculators, who rented them out to people who couldn’t afford anything better. Eventually, when the cost of maintaining the house got too much, they walked away. Gradually no one wanted to own the houses anymore. In the entire census tract shown in the picture of St. Louis’s North Market Street, only one house was sold during 2015. The price was $9,900.

When an area gets to that point, as families move out, or elderly homeowners pass away, the houses stay empty, and are sooner or later vandalized for the copper in the pipes, trashed by squatters or gangs, or set on fire. Eventually, the city may get around to knocking them down, usually to the relief of the remaining neighbors. Cleveland activist Frank Ford told me about how an elderly homeowner once buttonholed him about the empty house next door: “I don’t care if they fix it up or tear it down,” she said. “Just do something!”

Despite the robust urban revival, areas of concentrated poverty are growing in America’s cities and metropolitan areas. Urban Observatory’s Joe Cortright has studied the long-term trends in the nation’s larger cities and metro areas. He concludes: “A few places have gentrified, experienced a reduction in poverty, and generated net population growth. But those areas that don’t rebound don’t remain stable: they deteriorate, lose population, and overwhelmingly remain high-poverty neighborhoods. Meanwhile, we are continually creating new high-poverty neighborhoods.”24 While poverty itself is debilitating to body and spirit, decades of research since Kenneth Clark’s Dark Ghetto has shown how much more destructive it becomes when concentrated in areas of persistent, concentrated poverty.

Cortright found that out of 1,100 high-poverty neighborhoods in the fifty-one cities he studied in 1970, fewer than one in ten had “rebounded,” in that their poverty rates had declined from over 30 percent to below 15 percent, which was still at or below the national average. More than two-thirds of those areas still had poverty rates over 30 percent in 2010. Meanwhile, over 1,200 neighborhoods that had been low-poverty in 1970 had become high-poverty areas by 2010. All told, there were nearly three times as many high-poverty areas in these fifty-one cities in 2010 as in 1970.

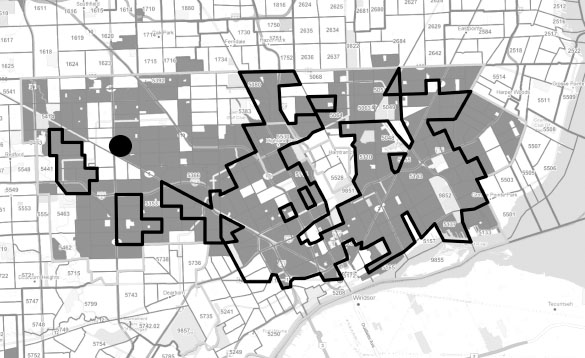

Cortright didn’t factor race into his study, but when we compare the location of areas in many cities that are both majority black and high-poverty in 2000 and in 2015, we find the same pattern: a few areas may no longer be majority black, high-poverty areas, but many more areas have been added. While a handful of areas in Milwaukee are no longer majority black, high-poverty areas, large parts of the city’s North Side have been added; all in all, the number of Milwaukee’s African American residents living in areas of concentrated poverty grew by 36,000 between 2000 and 2015, while the percentage of all African Americans living in those areas grew from 46 percent in 2000 to 58 percent, or well over half, by 2015. In the map of Detroit shown in figure 4-4, the areas outlined in black were ghetto areas in 2000, while the gray areas were ghetto areas in 2015. Detroit’s ghetto has spread from the central parts of the east and west side across the city, today including many of the city’s one-time middle-class neighborhoods to the northwest and to the east.

Figure 4-4 The spread of Detroit’s ghetto, 2000–2015. (Source: PolicyMap)

Tracking one small area, the black circle on the map of Detroit, over the past nearly fifty years sheds light on how urban neighborhoods change. This area, a small neighborhood known as Crary-St. Mary’s after its public school and its Catholic church, was built from the 1930s through the 1950s, a time mostly of prosperity and rapid growth in Detroit. From the beginning it was a middle-class neighborhood, with smallish but solid brick houses set back from the street by generous front yards; in fact, it was a modest, miniature version of nearby Palmer Park, where the Big Three executives lived in brick and stone mansions. It was a neighborhood of married couples and homeowners. As late as 1970, it was still entirely white. That changed almost overnight in the 1970s, though, as Detroit’s white middle-class families fled the city for the burgeoning suburbs. By 1980, the area was 84 percent black.

The skin color of the people living in the houses may have changed, but little else did. The great majority of the black newcomers were middle-class strivers themselves. They earned about the same as the people they replaced, and they owned their own homes, where they raised their families. The number of married couples with children in the area actually went up from 1970 to 1980. Things stayed pretty much the same through the 1980s. While there were subtle signs of change during the nineties, as the number of homeowners dropped slightly and incomes started to tail off, the area was still in fairly decent shape as the millennium ended. Few residents were poor, and few houses were empty.

Then Crary-St. Mary’s fell off an economic cliff. By 2015, the neighborhood’s population had dropped by a quarter. The number of poor residents more than doubled. The neighborhood became a concentrated poverty area, where nearly two out of five residents lived below the poverty level. At the same time, the number of “middle-class” people in the area, defined as people whose family income is more than double the poverty rate, fell by over half. That’s a low bar, less than $50,000 per year for a family of four. The number of homeowners dropped by more than 300, over a quarter of all the homeowners in this small neighborhood. By 2009, houses were selling for barely more than $10,000. The number of empty houses tripled, and people started to get used to living next door to boarded-up houses, as seen in figure 4-5. As the city became increasingly aggressive about knocking down empty houses, more and more vacant lots started to pop up in the neighborhood.

Whether Crary-St. Mary’s can be restored to its one-time vitality, and what that would take, is a complicated question. Here, though, the question is why it collapsed the way it did. It’s a complicated story, but an important one. It’s partly about what was going on in the United States, and partly about what was happening in Detroit, and how, when the United States caught cold, Detroit caught pneumonia. It’s also about race.

The story of how America went on a home-buying spree around the turn of the millennium, and its disastrous aftermath, has been told often. Without going into the sordid details, a toxic mix of subprime loans and predatory lenders; greedy, ignorant, or duped borrowers; and a public sector dominated by a combination of free-market fundamentalists like Alan Greenspan and heedless cheerleaders for an ever-rising homeownership rate all combined to set off a speculative frenzy of homebuilding and home-buying that sent house prices soaring through most of the United States.

Figure 4-5 Empty houses on Biltmore Street in Crary-St. Mary’s, Detroit. (Source: Google Earth)

Subprime lending began as what seemed, at least to lenders, to be a good idea. Traditionally, lenders offered a single set of financial products to “prime” borrowers. Based on a loan officer’s review of your credit, your work history, and so forth, you either made the cut or you didn’t. If you made the cut, you got a loan, and if you didn’t, you didn’t. As automated underwriting gradually took the place of loan officers’ judgment during the 1990s, people in the industry had a new idea. If we can predict risk from credit scores, they figured, instead of simply disqualifying “subprime” borrowers why don’t we adjust the interest rates on our loans to reflect the higher risk of making loans to them, so we can lend to subprime borrowers as well?

That makes sense, up to a point, although the “quants” who did the research badly overestimated their ability to predict future risk. But, as economists Randall Dodd and Paul Mills point out, for this kind of lending to work, “lenders must control the risks by more closely evaluating the borrower, setting higher standards for collateral, and charging rates commensurate with the greater risks.” That didn’t happen; instead, fueled by vast amounts of money from all over the world looking for a place to land, and the ease of turning mortgages into securities that could be sold to unsuspecting investors, a feeding frenzy ensued. By the early 2000s, as one lender at Countrywide Financial, a major player in the subprime frenzy, put it, “If you had a pulse, we gave you a loan. If you fog the mirror, we give you a loan.”26 Soon, increasingly exotic and untenable loan products were floating around, from loans with initially low “teaser” rates with payments that increased spectacularly after two or three years, and what were called “NINJA” loans (“no income, no job, no assets—no problem”).

What does this have to do with race? Everything. With a commission system that rewarded salespeople for making the most outrageous possible loans, real estate brokers and subprime mortgage lenders saw black—as well as Latino—communities, with their historically low homeownership rates, as a huge profit opportunity. As Emily Badger writes, “Banks that once ignored minority communities were targeting them now to make money, a practice that’s been bitterly referred to as ‘reverse-redlining.’”27 As a one-time Wells Fargo loan officer testified, they “had an emerging-markets unit that specifically targeted black churches, because it figured church leaders had a lot of influence and could convince congregants to take out subprime loans.”28 Black churches and other community groups were offered and readily accepted payment to host “mortgage fairs” and “real estate seminars” organized by lenders.

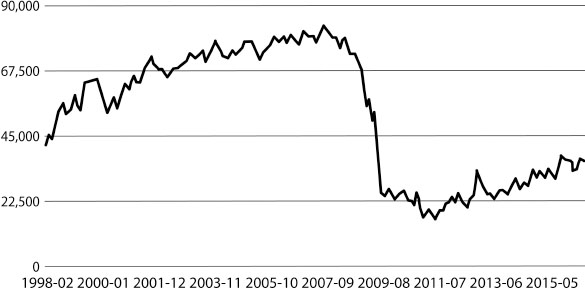

Detroit shared in the frenzy. Mortgages flowed like water, home prices rose slowly but steadily from 2000 to 2006, and the number of home sales rose dramatically, going from 5,000 in 2000 to nearly 30,000 in 2006. But the underlying reality was still that Detroit was hemorrhaging jobs and people, and for all the glitter spread by young “hip-hop mayor” Kwame Kilpatrick, whom the Democratic Party named one of the nation’s “10 young Democrats to watch” in 2000,29 the city was rapidly losing ground fiscally and economically. When the mortgage bubble burst, followed by the Great Recession, the city’s house of cards abruptly collapsed, as figure 4-6 shows vividly.

Figure 4-6 Detroit’s boom and bust: median sales prices for homes in Detroit, 1998–2016. (Source: Zillow.com)

House prices plummeted and foreclosures skyrocketed. Meanwhile, since the local tax assessor refused to reduce people’s property-tax assessments to reflect the reality that their houses had lost 80–90 percent of their value, homeowners were finding themselves with annual property tax bills of $3,000 or $4,000 on houses they’d be lucky to get $15,000 for if they put them on the market. By 2011, even as mortgage foreclosures were starting to slow down, tax foreclosures were taking off.

With thousands of homeowners losing their homes at foreclosure sales and tax auctions, a new breed of predatory investor began to show up. These investors did their arithmetic. They knew that it took at least three years of not paying taxes before the county took your property away. They realized that if you bought a house for $15,000 and rented it out, no questions asked, for $750 a month or $9,000 per year, and you didn’t pay your taxes or do any repairs that took more than duct tape, then at the end of three years you had gotten close to $27,000 back from rental of the house. That works out to a profit of $12,000 over three years, a nice return of better than 25 percent a year. At that point, you wouldn’t hesitate to walk away from the house, which by now was probably a near-total wreck, because you’d made your money. The people who were now buying houses in Crary-St. Mary’s were the people who’d done that arithmetic.

Detroit was now caught up in a vicious cycle of its own. As property values plummeted, and as the Great Recession took hold, municipal revenues fell. As revenues fell and employees were laid off, services declined. In 2001, Detroit had over 1,500 public-works employees, 665 workers in the recreation department, and 244 people running programs for children and youth. By 2012, the city had barely 500 people in public works, with 200 left in recreation, which now included what few youth programs the city still offered.30 Parks and playgrounds were abandoned, streetlights went out, and potholes never got filled. Even worse, the number of uniformed police officers went from 4,330 in 2001 to barely 2,700 by 2012; that year, Emergency Manager Kevin Orr cited FBI data that the Detroit police had solved only 11.3 percent of the murders, 8.1 percent of the robberies, and 12.8 percent of the rapes that took place in the city the year before.31

Like their white counterparts, some black middle-class families had been moving from cities to suburbs for years. Many others, though, held on, driven by pride in their neighborhoods and loyalty to their city. Nowhere was that loyalty stronger than in Detroit. As things got worse, though, those ties frayed and broke. Detroit activist Lauren Hood, whose parents moved out of the city in 2013 after being held up at gunpoint in the home they’d owned for forty-five years on the city’s northwest side, wrote that “the city is now losing those that stood by its side for the longest, those that toughed it out in the neighborhoods until the last possible second, the second a gun was pointed at their heads! I become enraged when I hear people say the way to improve the city is to increase the tax base…. Detroit is hemorrhaging tax base every time a family like mine, and that of [my] dad’s new friend, flees, traumatized, to a ‘safer’ suburb.”32

In 2005, Detroit had more than 68,000 middle-class black households, families making $50,000 or more. By 2015, the number (with the floor adjusted to $60,680 to account for inflation) had dropped to 35,500—barely half as many. While it would be an oversimplification to say that fully half of the city’s middle-class black families had moved out of the city in ten years—some may have lost income, and others passed away—it is safe to say that a very large number did leave, mostly for affordable suburbs like Southfield or Farmington Hills.

Detroit is an extreme case, but the same pattern can be found in city after city; as the Economist put it in 2011, “from Oakland to Chicago to Washington, DC, blacks are surging from the central cities to the suburbs.”33 Speculating on the reasons for the exodus, Akiim deShay of BlackDemographics.com, says, “Crime is one of them, a big one. Schools are a big one, as well…. You have a whole upwardly mobile group who can afford a better life, and they are pursuing it.” DeShay adds that he moved his family from Rochester to the suburbs more than fifteen years ago. “When we left, I felt guilty, because I felt like I was contributing to the problem,” he said. “And in a sense, I was.”34

The upshot is that the black population of America’s older cities is shrinking, and it is growing poorer. From 2000 to 2015, the African American population fell in almost every city, in some cases by a small number, but in others by hundreds of thousands, as in Detroit and Chicago.

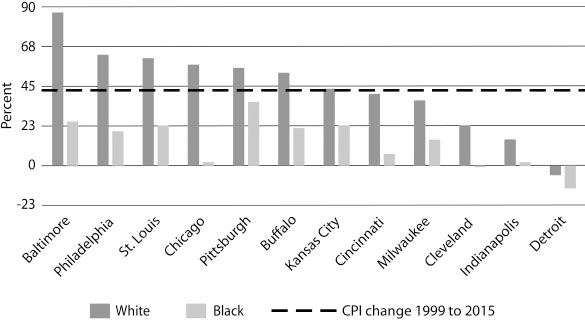

The juxtaposition of black middle-class flight with the in-migration of the largely white Young Grads has created a situation in which the black-white income gap in the cities, wide to begin with, has grown steadily wider since 2000. Of twelve large cities shown in figure 4-7, white income gains outstripped those of black families in all twelve; moreover, when measured in real dollars adjusted for inflation (the horizontal dotted line), black families lost income in every city, coming close to breaking even only in Pittsburgh. White families, on the other hand, held their own against inflation in eight of the twelve cities shown.

Figure 4-7 The widening racial gap: change in median household income by race, 1999–2015. (Source: US Census)

The widening racial income gap has fueled the economic and racial polarization of these cities. In 2000, the median black family in Baltimore earned 61 percent of the income of the median white family. By 2015, this figure had dropped to 48 percent. The typical white family, not only in Baltimore, but in Chicago, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Kansas City, earns more than twice as much—in Chicago and Cincinnati, nearly three times as much—as their African American counterpart. And, as the remaining black populations in the cities became poorer, they became increasingly stuck in place, in Patrick Sharkey’s phrase, in ghetto areas of concentrated poverty, increasing racial polarization in space along with income. Baltimore is no longer legally segregated as in George McMechen’s day—at least a handful of African American families live in every part of the city—but the reality is not that different.

The flight of the black middle class, and the increased concentration of the remaining African American population into concentrated poverty ghettos, is significant not only in terms of the demographics and economic makeup of the reviving legacy city, but is likely to have equally significant effects on the distribution of power, influence, and identity in these cities. Those effects are just beginning to emerge.