For over four centuries before 1898, Spain had ruled over a vast and profitable overseas empire, based on her Caribbean, Central and South American possessions. Although Mexico and Peru provided the greatest source of mineral wealth (i.e. gold and silver), Cuba was regarded as the linchpin of this empire, and Havana the most important harbour in the Americas. Foreign interlopers nibbled away at the Spanish Main, and following the involvement of Spain in the Napoleonic Wars (1808–1815) many New World provinces took the opportunity to seize independence. By 1860 only Cuba and Puerto Rico were left to remind the Spanish of their former glory in the Caribbean, and Cuba was causing severe problems for the government.

Seeds of unrest had spread throughout Cuba, and in 1868, Cuban insurgents launched the Ten Year War (1868–78), the First Cuban War of Independence. Although a military failure, it provided the base from which Cuban insurgents would launch an unremitting guerrilla war against the Spanish army of occupation, destroying sugar crops, disrupting transportation and attacking isolated troop outposts.

During the Ten Year War, American sympathy for the cause of the Cuban revolution grew, fuelled by atrocity stories in the press. The end of the war brought an uneasy peace, while exiled revolutionary leaders like Maximo Gomez, Antonio Maceo and José Marti plotted to renew the struggle. By 1895 they were ready, this time with the American press following their every move. The revolution got off to a bad start, however, and the key figures of Maceo and Marti were killed.

Maj.Gen. Henry W. Lawton, commander of the 2nd Division of Shafter’s V Corps. Pinned at El Caney, his command was unable to participate in the Battle of San Juan. Sketch by Frederic Remington. (Private Collection)

The Spanish appointed Gen. Weyler as Governor of Cuba, and his policies were singularly effective. A trocha (or fortified line) was dug, splitting the island in two. A reconcentrado policy forced the rural population into fortified villages, but the savagery of the war and resultant destruction of crops and animals led to mass starvation. This only provided fuel for the American press. By 1897 the insurgents were crushed everywhere but Santiago, but Weyler’s policies, though militarily sound, were a political disaster. He was replaced by the more lenient Gen. Blanco, but by that time the damage was done. With the American press and public at fever pitch, United States intervention seemed inevitable.

On 15 February 1898, the battleship USS Maine blew up in Havana harbour. For years, Spain’s attempt to regain colonial power against a rag-tag army of Cuban insurgents had been watched by the American public, whose sentiments had been inflamed by anti-Spanish bias in the press calling for the island’s independence. Public feeling had been running so high that the issue was discussed in terms of Cuban independence or war. The mysterious disaster which overtook the USS Maine was a spark sufficient to ignite the fire of war, and on 25 April 1898 Congress declared that a state of war had existed between the USA and Spain since 21 April. Only three days earlier, Congress had passed a mobilisation act which represented a compromise between the National Guard enthusiasts and army reformers. It called for a force made up of regulars and volunteers, many of the latter supposedly being raised from men immune to tropical diseases, such as yellow fever. Since Spain was obviously incapable of invading the United States (apart from in the overwrought imagination of a few alarmists), and since Cuba could not be freed without direct intervention, a number of regiments organised as the V Corps were sent to the ill-equipped port of Tampa, Florida, for eventual embarkation to Cuba.

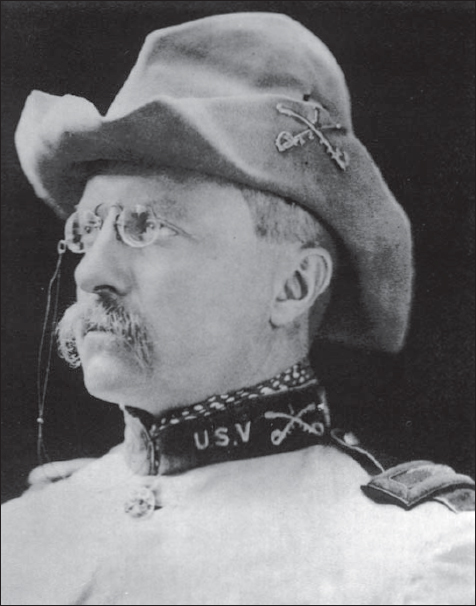

Lt.Col. Theodore ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt, acting commander of the 1st Volunteer Cavalry Regiment (the Rough Riders). The future President of the United States secured his political future by his performance during the campaign. (Library of Congress)

Over 200,000 soldiers gathered in several camps across the United States: Chickamauga, Georgia; Falls Church, Virginia; Mobile, Alabama; San Francisco, California; and Tampa, Florida. Of these, the last became the new focus for the war effort. As the days wore on, an increasing quantity of men and matériel was gathered at Tampa, and turned into something resembling a military organisation. Few officers had experience of the logistics and planning required to perform such a task, so they had to learn everything from trial and error. The only senior officer in Tampa to have ever commanded a formation bigger than a regiment was Gen. Wheeler, who had last fought at the head of the Cavalry Corps of the Confederate army of the Tennessee in 1865. His experience was also to have a decisive impact on the outcome of the campaign.

Troops gathered in Tampa from all over America, and were formed into regiments that often had never even fought or trained together before. With only seven weeks of preparation, the volunteer troops went into battle with the bare minimum of military training and discipline. The process did at least help to turn them from jingoistic patriots into a practical army of militiamen, and enthusiasm and adaptation made up for lack of expertise during the ensuing months.

Regular troops arrived from garrisons scattered across the American West. After years of serving in small detachments and in isolated garrisons, they had rarely seen their parent regiment operating together as a unit. The learning curve of the regulars as they trained at Tampa was almost as steep as that of their volunteer compatriots. As the muddled logistical situation unravelled itself, plans were laid for sending the troops into action.

When word reached the War Department that the only Spanish naval squadron in the Atlantic was blockaded in Santiago de Cuba, orders were telegraphed to Gen. Shafter in Tampa to prepare the troops for immediate departure. Regiments scrambled for the waiting transport ships and even fought among themselves for places on board. ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt commandeered a ship for the Rough Riders and refused to disembark, thereby assuring a place for the volunteer cavalry regiment in the campaign. The cavalry mounts were not so lucky. Due to insufficient transports, Gen. Wheeler’s cavalry were forced to leave their horses behind. Only the artillery and a handful of officers would be allowed to load their horses. Eventually, 16,300 men, 2,295 horses and mules, 34 artillery pieces, four Gatling guns and 89 journalists were loaded and ready to sail. They continued to wait for several days while the navy searched for a ‘phantom’ Spanish cruiser. Finally, on 12 June they were given orders to sail. The invasion of Cuba was underway.

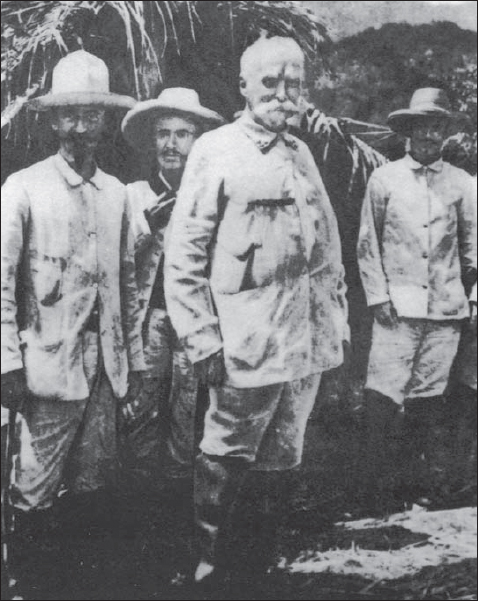

Gen. Calixto Garçia and staff, commander of the Cuban insurgents in eastern Cuba. A gifted commander, he was criticised for not lending more support to the US army. In reality, his guerrilla tactics did much to ensure an American victory. (National Archives)