The Spanish had not just waited passively to be attacked since the skirmish at Las Guasimas. Over two miles of trenchworks snaked back and forth along the San Juan Heights, part of a hastily prepared fortified line that extended from Aguadores on the coast to El Caney, eight miles to the north-east. The forward positions of this line were for the most part sited on high ground to the east of the San Juan River. The principal area of defence was itself on San Juan Heights, and an impressive line of trenches defended the area around the San Juan blockhouse. The flanking sections of the Heights were also lined with trenches forming almost a second line, where Spanish troops could protect the flanks of the main position. Barbed wire and gun pits completed the obstacles facing the Americans on the Heights, but both guns and wire were in such short supply that the wire was placed in areas where the guns had no clear line of fire. Earth from the trenches was removed to the rear slope of the Heights, to partially hide the earthworks. A forward position on Kettle Hill allowed the Spanish infantry to command the tree line less than 500 yards away, where the Camino Real road and another trail emerged from the jungle. This was the expected American axis of advance. The barbed wire was mainly stretched in front of Kettle Hill, on both banks of the San Juan River. The Americans were therefore facing what amounted to three lines of defence. The inner defences of the city of Santiago provided a fourth line. Centred on the Fort Canovar and the Reina Mercedes Barracks, Spanish reinforcements were held in reserve, 500 yards behind the front line.

Officers and war correspondents conferring after the skirmish at Las Guasimas. This is the same impromptu conference seen in the preceding photo. Wheeler is second from the left, and Roosevelt and Woods can be seen conferring in the background. (National Archives)

Artillery supplies and ammunition being brought up by pack animals along the Camino Real between Las Guasimas and Sevilla. In places the misleadingly named ‘Royal Road’ was little more than a dirt track. (National Archives)

Two miles north of the San Juan blockhouse the Spanish defensive line stopped at a point where it overlooked the stone bridge crossing the San Juan River. The bridge carried the road from Santiago to El Caney, and was by far the best metalled road on the battlefield. This provided another avenue for reinforcements to reach the fortified village. El Caney itself was sited two miles north-east of the stone bridge, and almost four miles from the American forward positions at El Pozo. A tiny track passed the hamlet of Marianage along the way. El Caney itself was a small village of palm-thatched huts and tin-roofed buildings, but did boast a large stone church.

The village had only one previous claim to fame: Cortez was supposed to have prayed in the church the night before he sailed off to conquer Mexico. The village that witnessed the beginnings of the Spanish Empire would also play a part in its demise. Strategically, El Caney guarded the flank of the Spanish position, and also posed a threat to any American advance on San Juan. Spanish reinforcements could use it as a secure point to launch a counterattack against the exposed American left flank.

The principal defensive position within the village perimeter was a substantial stone fort called El Viso, larger than the normal Spanish blockhouse. Sited on a hillock 400 yards south-east of the village, it commanded the approaches to the Spanish position from the south and east. Four blockhouses protected the village itself, and the village perimeter and El Viso Fort were ringed by a line of trenches, rifle pits and barbed wire. Inside the village, buildings were loop-holed and prepared as a final defensive line.

Other approaches to Santiago were also defended. The Spanish still feared another American landing, either to the west of the city or at the harbour entrance itself. Consequently, many Spanish troops were deployed to defend Morro Castle, which dominated the harbour entrance, as well as the secondary coastal batteries flanking both sides of the harbour channel. Fear of Cuban insurgent attacks also tied down troops in defences to the west of the city, around the village of El Cobre. The inner ring of city defences bristled with guns, wire and well-constructed forts, blockhouses and trenches. A direct assault on the city or on its harbour defences would be a costly undertaking. A further line of small blockhouses lined the hills to the north, guarding the city water supply from guerrilla attacks.

Despite the substantial defensive positions built by the Spanish, their defences were flawed by a simple lack of troops. Most of those that were in the area were not in a position to defend against a direct American assault. On 22 June, Gen. Linares called for 3,600 reinforcements from the town of Manzillo, 45 miles to the west. 1,000 sailors from the fleet guarded the western approaches to the city, while a further 1,200 guarded the coastal defences. A garrison of 500 men was stationed at El Caney, and a further 500 manned the entrenchments on San Juan Heights and Kettle Hill. This left over 9,000 more soldiers, engineers, gunners, volunteers and civil guards in the city itself and its inner defensive perimeter. Why didn’t Linares bolster his front line on San Juan Heights, the obvious area for the Americans to attack?

Building a corduroy road over the worst stretches of muddy stream crossings on the road from Las Guasimas to Sevilla. Poor conditions made supplying the army an almost impossible task. (National Archives)

Troopers of the Cavalry Division fording the Aguadores River near El Pozo, on their way up the Camino Real, shortly after dawn on 1st July 1898. The Spanish were only one and a half miles away, and soon the column would come under heavy fire. (National Archives)

Even before the Americans landed at Daiquiri, the Spanish troops in Santiago Province were in dire straits. Supplies were low, and guerrilla action meant that local contractors were unable to easily replenish their stocks of meat and grain from the surrounding countryside. Similarly, poor administration in the Army High Command meant that military supplies were not reaching the province. Gen. Garçia and his Cuban guerrillas had effectively isolated the city. The naval blockade by the US navy meant that resupply by sea was out of the question, and guerrilla attacks also prevented the supply of isolated posts some distance from the city. By the time the Americans landed, the garrison and inhabitants of Santiago had only enough food for a month. Although over 12,000 troops were scattered elsewhere in the province, there were not enough supplies in the city to feed the extra mouths. The troops would have to remain dispersed until supplies could reach the city. Similarly, the numbers of Cuban insurgents massing in the hills around the city was estimated at around 15,000. Gen. Linares’ main fear was that guerrillas would attack Santiago and destroy his few remaining supplies while his forces were pinned by the Americans and unable to respond. The Spanish general therefore kept his troops in readiness within the city and awaited developments.

The call for reinforcements from Manzillo also included a plea for food and ammunition. Once these supplies arrived, the Spanish might be able to concentrate their forces and bolster their defences. After the skirmish at Las Guasimas, it was felt that an offensive action was unnecessary. By creating an impregnable defensive position, and with the yellow fever season approaching, the Spanish hoped that the American army would simply wither away.

During the late afternoon of Saturday 30 June, columns of US troops snaked their way up the trail from Sevilla to El Pozo. ‘Regiment after regiment passed by’ noted Roosevelt, ‘varied by bands of tatterdemalion Cuban insurgents, and by mule trains with ammunition.’ The army bivouacked around El Pozo by midnight, and waited for dawn.

Gen. Shafter and his aides had already seen the Spanish trenches on the San Juan Heights, and the plan to capture them was brutally simple. Lawton’s division would capture El Caney, thus securing the army’s right flank. It would then move south-west to attack San Juan Heights. It was estimated that the El Caney operation would last two hours. The two remaining divisions of the army would march down the road from El Pozo to Santiago, which ran alongside the Aguadores River. The trail emerged from the jungle into an open grassy plain which formed the meadowland surrounding the shallow San Juan River. Beyond this lay the Heights, and the Spanish. The army would simply enter the meadow, deploy, cross the San Juan River, make a frontal assault on the Heights, and thus win the day. Once the Heights were in American hands, the city of Santiago and the fleet in its harbour would lie at the mercy of the invaders. Shafter wrote: ‘It was simply going straight for them. If we attempted to flank them or dig them out … my men would have been sick before it could be accomplished, and the losses would have been many times greater than they were.’ A newly-arrived Michigan volunteer regiment would make a diversion along the coast from Siboney towards Aguadores in an attempt to prevent troops reinforcing the Heights. Apart from the El Caney operation, there was no other subtlety to the plan. Inter-service rivalry also made Shafter decline the navy’s offer of gunfire support, and the same reason prompted him to keep veteran US Marine reinforcements out of the fight. This was going to be the army’s big day.

Gen. Wheeler was laid low with fever, and Gen. Sumner assumed command of the Cavalry Division. Young was also sick, and his place as brigade commander was taken by Col. Wood, leaving Lt.Col. ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt to assume command of the Rough Riders. As the senior officers prepared their troops that night, they and the ever-present journalists noted an air of intense excitement. After months of waiting, the next day would bring about the deciding battle of the war. Lt.Col. McClernand, Gen. Shafter’s adjutant general, found that his commander would not be directing the battle. ‘At 3:00am on the morning of July 1 I entered the tent of the Commanding General. He said he was very ill as a result of his exertions in the terrifically hot sun of the previous day, and feared he would not be able to participate as actively in the coming battle as he had intended.’ It fell upon the divisional commanders (Kent and Sumner) to direct operations. In practice, they would mostly be unable to directly influence the battle due to geographical factors, and effective control devolved to brigade and regimental commanders. As Roosevelt put it, ‘the battle simply fought itself’.

A US column marching forward past Sevilla towards El Pozo during the early evening of 30 June 1898. Gen. Shafter’s headquarters were immediately behind the photo, on the northern outskirts of Sevilla. (National Archives)

At the same time on the Spanish side of the lines, Gen. Arsenio Linares was also awake in his headquarters at Fort Canosa, between the Heights and the city. With only 10,000 troops available, his lines were spread thinly. Starvation already threatened the city, and troops had to be deployed to protect the roads to the west, guard outlying villages with their food supplies and secure the aqueduct supplying the city. The threat from Cuban insurgents meant that only 521 men waited for the Americans on San Juan Heights supported by two Krupp light artillery pieces. A further 1,000 men waited at Fort Canosa in case they were called upon to reinforce the Heights.

An overturned supply wagon at a ford crossing outside Sevilla. Inadequate provision of supplies would delay the advance of the army beyond Sevilla for almost a week. (National Archives)

The 6,650 men of Gen. Lawton’s US Second Division approached El Caney at dawn on 1 July 1898. They had marched north up the track from El Pozo, passing through the hamlet of Marianage on the way. Two sections, comprising two light 3.2 in. field guns each, supported the troops. The artillery was under the command of Capt. Allyn Capron, whose son had been killed at Las Guasimas. They deployed into position on a low hill covered in bushes, about a mile to the south of El Viso fort, which was regarded as the linchpin of the Spanish defences, and would be the principal target. Meanwhile, the infantry moved forward, Gen. Ludlow’s brigade circling to the left of the village and Gen. Chaffee’s to the right, towards the high ground to the east of the fort. The brigade commanded by Evan Miles was still marching up from Marianage. The time was now 6:35am, and Capron was given permission to open fire.

THE SPANISH DEFENDERS AT EL CANEY

The Spanish garrison at El Caney was well ensconced in a network of trenches, rifle pits, barbed wire and blockhouses. Initial estimates that the assaulting American troops would clear the village in less than two hours proved to be hopelessly optimistic. The key positions in the defence works were the stone fort of El Viso and the scattering of wooden blockhouses that ringed the village. The attackers surrounded the village and while Capron’s battery shelled El Viso, the US infantry regiments exchanged fire with the defenders from as close as 200 yards away.

The Spanish inflicted so many casualties on the 22nd Massachusetts Volunteers that the regiment was pulled back into reserve. Smoke from their obsolete black-powder weapons had betrayed their positions to the Spanish, who could return the fire with greater accuracy. The struggle carried on for most of the day. Once the fort of El Viso had been captured by an American assault, the Spanish pulled back to a last line of defence in the village itself, and were only finally overcome after bitter fighting. Although hopelessly outnumbered, they had held up Lawton’s division long enough to prevent them from participating in the main battle for San Juan Heights.

Their guns were considered obsolete by contemporary military standards. Not only did they fire black-powder shells that created tell-tale smoke, giving away the battery position, but they were not self-recoiling, which hindered accuracy as well as speed of reloading: nor were they fitted with sights to allow indirect fire. As an American artillery officer put it: ‘Yet such was our backwardness in military science that the whole army was ignorant of the tremendous advance in Field Artillery that in 1898 was an accomplished fact.’

Capt. Allyn Capron with his battery officer at dawn on 1 July. The battery is shown in the position it established during the night, and is waiting for orders to open fire on the Spanish fort of El Viso. No Spanish guns were in a position to return the fire. (National Archives)

Capt. Lee, a British military observer from the Royal Engineers, recalled the scene before the battery opened fire: ‘Profound quiet reigned, and there was no sign of life beyond a few thin wisps of smoke that curled from the cottage chimneys. Beyond lay a fertile valley, with a few cattle grazing, and around us on three sides arose, tier upon tier, the beautiful Sierra Maestra Mountains, wearing delicate pearly tints in the first rays of the rising sun.’ This peace was about to be shattered.

Although the guns were trained on the fort, the first target to present itself was a group of horsemen, riding towards the American position from the village. The barrage overshot the target, which was fortunate, as the riders later turned out to be Cuban allies, 50 insurgents who had been keeping the village under observation. The horsemen disappeared from sight and the guns began firing on the fort. Rifle fire from the village perimeter opened up in response. While the Spanish used smokeless powder for their Mauser cartridges, the American artillerymen revealed their position with the smoke from their guns. However, despite the obsolescence of the artillery the shells were beginning to make an impression. One of the shots breached the stone wall of the fort, and a barrage lasting just over three hours caused visible damage to the fort and its surrounding earthworks, but failed to stop the hail of fire coming from the Spanish trenches. Capt. Lee reported seeing the Spanish soldiers in their ‘light blue pyjama uniforms and white straw slouch hats’ dive for cover into their slit trenches. ‘A fresh row of hats sprouted from the ground like mushrooms and marked the position of the deep rifle pits and trenches on the glacis of the fort and at various points around the village. For the next quarter of an hour our battery kept up a leisurely fire upon the stone fort, eliciting no reply, and so little disturbing the white hats that someone suggested they were dummies.’

The village of El Caney, viewed from the ridge containing El Viso Fort. The church is on the right of the picture, where the final Spanish resistance was overcome. (National Archives)

By this time, Gen. Chaffee’s brigade had worked its way round to the hills to the east of the village, and brought down a continuous return fire on the defenders. Their position also served to cut off any chance of Spanish retreat north into the hills, and a small number of Cuban irregulars supported the extreme right flank of Chaffee’s position. Meanwhile, Gen. Ludlow’s brigade took up positions south of the village, supporting the battery with rifle fire. Ludlow extended his left flank as far as the Santiago to El Caney road, so he was in a position to intercept any relief attempt from the city. A sunken section of trail to the east of the village provided an improvised form of trench, and served to anchor the left flank of the American line. At this point it was within 100 yards of the western edge of the village, and under constant rifle fire from the fortified houses. Col. Miles was still approaching the battlefield with the 3rd Brigade of Lawton’s division, and the head of his column passed Capron’s battery at 11:00am. Miles was ordered to hold the centre, facing the El Viso Fort, and when ordered, his troops were to advance on the fort in support of Chaffee’s brigade. A fourth, Gen. Bates’ independent brigade, was still moving up to join Lawton’s forces from El Pozo and Marianage. Although the four American guns helped to reduce the fort, the battle was to be decided by rifle fire.

What Gen. Shafter planned as a small, secondary operation turned out to be the hardest-fought engagement of the campaign. A small garrison of hopelessly outnumbered Spanish defenders held their own against a reinforced American division. Planners expected the battle to last two hours. Instead it took almost a third of the American army a whole day to capture the village.

A blockhouse and defence line at El Caney, looking east. The Spanish held these positions for almost a day, despite being heavily outnumbered. (National Archives)

For around an hour, from 9:00am, the left and centre of the American line were engaged in a vicious and deadly firefight. Gen. Ludlow had his horse shot from under him, and his soldiers burrowed into the soil or crouched behind trees, trying to avoid the hail of Mauser bullets. The most intense exchange of fire was on the extreme left, where the 2nd Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment held their position astride the sunken road. Their colonel was wounded in the exchange, although overall casualties did not reflect the intensity of the fire. It appeared that for the most part, both sides tended to fire over the heads of the enemy. To inexperienced troops, the fire must have been terrifying. ‘The buggers are hidden behind rocks, in weeds, in the underbrush. We can’t see them, and they are shooting us to pieces’ one volunteer told a reporter. The Volunteers, armed with black-powder Springfield rifles, were more of a liability than an asset and Ludlow decided to pull the regiment out of line, replacing them with two regular regiments armed with modern Krag rifles. The Massachusetts regiment was placed in reserve about 300 yards to the south-west, where they served as a blocking force which would prevent reinforcements reaching the village from Santiago.

A street in El Caney, looking north-east. Although many of the buildings were flimsy, a handful of stone houses and the church served as mini strongholds. (National Archives)

Capron’s Battery fired shell after shell into the ruins of the El Viso Fort, and also bombarded the rifle pits and trenches covering its southern side. Chaffee continued to edge his troops forward. The US 7th Infantry held ground behind and to the east of the fort, where it could cover the rear of the Spanish defences as well as the eastern side of the village itself. A withering Spanish fire prevented any further advance. The regiment was effectively pinned down until the fort was neutralised. The remaining two regiments of Chaffee’s brigade (the 12th and 17th Regiments) moved into position on the south-eastern slope of El Viso Hill. They found that a slight dip in the ground protected them from the worst of the Spanish fire, and the regiments lay low, preparing themselves for the inevitable assault on the fort. At around 10:00am, Gen. Ludlow ordered his men to cease firing, and they rested and smoked while badly needed ammunition supplies were brought up from the rear. The Spanish fire also slackened, as both sides prepared themselves for the renewal of the fighting. For the next three hours, only the occasional report of Spanish and American sharpshooters firing on exposed targets broke the silence. By noon the temperature was well over 90º Fahrenheit, and the humidity made the air damp and difficult to breathe.

Col. Miles was ordered to insert his brigade between those of Ludlow and Chaffee, and his troops also prepared for the assault. By noon they were in position, about 800 yards from the Spanish fort. Dead and wounded were taken to the rear. Lt. Moss of the 25th (‘Negro’) Regiment heard stretcher-bearers tell his men: ‘Give them hell, boys. They’ve been doin’ us dirt all morning.’ At midday a message arrived at divisional headquarters from Gen. Shafter. Concerned by the delay taken in what should have been a quick and relatively easy engagement, Shafter wrote: ‘I would not bother with little blockhouses. They can’t harm us. Bates’ Brigade and your Division and Garcia should move on the city and form the right of the line, going on Sevilla road. Line is now hotly engaged.’

The sound of the battle raging around El Caney had all but drowned out the increasing sounds of battle to the south at San Juan Hill. Shafter wanted Lawton and his attached Cuban allies to finish the job in hand and move towards the sound of the guns at San Juan. His reference to the Sevilla road was meant to be a crude indication of divisional areas. The troops of Kent’s Division and the cavalry would make the main assault on the San Juan Heights, and Lawton would take the secondary objective of the extension to the main San Juan position, west and north of Kettle Hill and the blockhouse. The break in firing around El Caney gave Gen. Lawton the opportunity to size up the task ahead of him for the first time. He realised that the fortified village would be a far harder objective to capture than anyone had anticipated. Although he had the option of moving the brigades of Miles and Bates around the village and sending them towards the San Juan River to the west, he felt his two engaged brigades needed all the support they could get. All four brigades would be fed into the forthcoming attack, and Shafter and the rest of the army would have to perform as best they could without support.

At around 1:00pm, firing began again from the left, where Gen. Ludlow’s brigade was ordered to open fire in support of the assault on the fort. Gen. Lawton ordered Chaffee and Miles to advance up the hill. A first line consisted of the 4th and 25th (‘Negro’) Regiment from Miles’ brigade, with the 12th Regiment of Chaffee’s brigade to their right. A second line formed from the remainder of both brigades (the 1st and 17th regiments) advanced 200 yards behind the first. The first 200 yards from the positions at the foot of the hill were screened by a double row of trees running alongside a small track. Beyond this lay a barbed wire fence and an open field of pineapples. Further up the hill, a belt of scrub offered a small degree of cover, but the final 400 yards would consist of an increasingly steep slope, where the knee-high sawgrass offered no cover whatsoever. Lt. Moss recalled what happened after the troops crossed the barbed wire fence: ‘Ye Gods! It’s raining lead! The line recoils like a mighty serpent, and then in confusion, advances again! The Spaniards now see us and pour a murderous fire into our ranks! Men are dropping everywhere … the bullets cut up the pineapples at our feet … the slaughter is awful! … How helpless, oh how helpless we feel! Our men are being shot down at our very feet, and we, their officers can do nothing for them!’

The US 7th Infantry Regiment firing on El Caney from the north. These troops formed part of Gen. Chaffee’s Brigade. Sketch by C.M. Sheldon. From Leslie’s Weekly, August 1898. (Monroe County Public Library)

El Viso Fort viewed from the south, showing the approach route of the US 12th Infantry Regiment in their storming of the fortification. The photograph was taken from the edge of the pineapple patch where the Spanish fire was so severe it almost stalled the attack. (National Archives)

Nervous troops and officers looked towards Chaffee, who was leading the assault of the first line. Standing in the middle of the pineapple patch, he ordered that the advance was to continue. He realised that the Spanish had zeroed in their rifles on the barbed wire fence and pineapple patch, and a rapid advance could well be the only way to avoid further casualties. By this time the line had been broken into clumps of men, seeking cover wherever they could find it. A fold in the ground on the right wing of the first line offered a likely avenue of advance, and a company of the 12th Infantry spearheaded the way, doubled over to remain protected from the Spanish fire. Hopelessly intermingled, the remaining units of the first line also probed forward as best they could. Now within 200 yards of the enemy trenches, the Americans found themselves able to see the Spanish troops inside the fort and the surrounding rifle pits. For the first time since the advance began, the Americans were able to fire on the enemy. With fewer than 200 defenders on the hill and no fewer than 1,500 attackers in the first wave alone, the outcome was never in doubt.

The stone fort at El Viso, pictured on the day after the battle for El Caney. The damage caused by artillery fire from Capron’s battery was substantial. (National Archives)

‘Our firing line is now no more than 150 yards from the fort, and our men are doing grand work. A general fusillading for a few minutes and then orders are given for no one but marksmen and sharpshooters to fire. Thirty or forty of these dead shots are pouring lead into every rifle pit, door, window and porthole in sight. The earth, brick and mortar are fairly flying! The Spanish are shaken and demoralised; bareheaded and without rifles, they are frantically running from their rifle pits … our men are shooting them down like dogs. A young officer is running up and down, back of the firing line and … is exclaiming; Come on men, we’ve got them on the run. “Remember the Maine!” Shouts a Sergeant. Four are shot down in the door of the fort. A Spaniard appears in the door … and presents … a white flag, but is shot down. Another takes up the flag, and he too falls.’

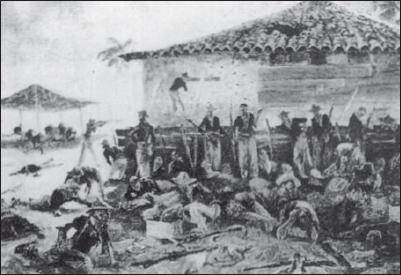

The storming of the Spanish fort of El Viso. The fort would prove to be the key to the El Caney defences. Painting by Frederic Remington. (Frederic Remington Collection)

The interior of El Viso Fort immediately after its capture. The interior apparently resembled ‘a charnel house’. Sketch by C.M. Sheldon. From Leslie’s Weekly, August 1898. (Monroe County Public Library)

Officers managed to stop the firing, and troops moved forward to secure the small battered fort. In the lead was a journalist, James Creelman, of Hearst’s New York Journal. In a seemingly schoolboy fit of bravado he helped spearhead the attack, and was trying to recover the fallen Spanish flag outside the fort when he was wounded. The fort interior was found to be full of dead and wounded, and the floors slippery with blood. Capt. Lee noted that the surrounding trenches were: ‘floored with dead Spaniards in horribly contorted attitudes … Those killed … were all shot through the forehead, and their brains oozed out like white paint from a colour tube’. Numerous shrapnel wounds amongst the casualties in the fort bore witness to the efficiency of the gunners of Capron’s Battery, and the interior walls were pockmarked with bullets, fired during the remaining minutes of the assault. A handful of Spanish prisoners surrendered, while a few others fled down the reverse slope of the hill, covered by fire from defences in the village itself.

At around 1:30pm, the situation looked grim for Gen. Vara del Rey and the remaining Spanish defenders. Retreat into the hills to the north of the village was impossible, because Cuban insurgents had blocked that avenue of retreat. Communications with Santiago were cut, and there was little hope of reinforcements reaching the garrison from the city. The Americans held El Viso, the strongest defensive point on the village perimeter, and their position now overlooked the Spanish trenches in the village. With fewer than 300 defenders remaining and able to fight, the Spanish faced odds of about 20 to 1. There was no doubt that the Americans would prevail. As well as the immediate situation in the village, Gen. del Rey was by now aware that the Americans were also assaulting San Juan Heights, and were directly threatening Santiago itself. He realised that his force had caused a substantial disruption to the American plan of attack, and the division facing him would be unable to reinforce the main American assault to the south. By denying Shafter over one third of his army, he might buy enough time for the Spanish to reinforce the city and repel the main American attack. He decided to continue the unequal fight.

Spanish prisoners captured after the battle at El Caney. Most defenders were either killed or wounded, and the dead included the local commander Gen. Vara del Ray and his two sons. (National Archives)

The Americans milling around on top of El Viso Hill had little opportunity to rest on their laurels. A heavy fire opened up from the village, the new defensive line centred on a blockhouse on the south-eastern corner. From there a line of trenches and wire ran west to the south-western corner of the village, where another blockhouse served to anchor the Spanish position. To the north of this, along the western edge of the village, Spanish marksmen in fortified houses continued to fire on Ludlow’s troops in the sunken road. The 2nd Brigade continued to fire on the Spanish positions, and covered by this fusillade, men from the remaining two brigades ran down the reverse slope of the hill and along a crest line running parallel to the village. Regiments were jumbled together, and discipline seemed to have been lost completely. This did remove many of the men from the exposed hilltop and brought them into a position where they could pour fire down from the crest on the nearest blockhouse, 200 yards to the west. One American officer records the incident:

‘As long as we remain in our present position, we can accomplish but little, as the walls of the blockhouse are impervious to our bullets. It is therefore decided to rush forward and change direction to our left, thus gaining a position facing, and slightly above the blockhouse … The line is now occupying its new position … some of our men are shooting into the town, and others are shooting down through the roof of the blockhouse … the Spanish are falling.’

This enfilading fire forced the defenders to abandon the blockhouse, and the Spanish withdrew from their line along the edge of the village, taking up a last stand in the central and western part of El Caney. A handful of defenders still held the western blockhouse and the stone church, and buildings between them were loopholed for defence. Gen. del Rey was reportedly seen on horseback, exhorting his men to give one final effort. As Ludlow’s men advanced to capture the abandoned Spanish forward positions, they were subjected to steady rifle fire from the village itself. With the rest of the division closing in on the village centre from the east, sheer weight of numbers and lack of ammunition on the part of the defenders brought resistance to a bloody end. A hail of shots was fired on the Spanish positions, and by 3:00pm the resistance was over.

Gen. Joaquin Vara del Rey was killed in the final minutes of the action as he directed the last stand from the plaza in front of the church. Wounded in the legs, he was being placed on a stretcher when he was struck in the head. He died instantly, and with him went the Spanish will to continue the bloody fight. His two sons, serving as aides, were also killed in the action. His second-in-command, Lt.Col. Punet, ordered that the surviving defenders should break out to the north-west, to avoid capture. With just over 100 men left unwounded, Punet’s action succeeded, and slipping round the flank of Ludlow’s brigade, over 80 men made it back to Santiago. Of the 520 Spanish defenders, 235 had been killed and a further 120 were taken prisoner.

The approach march of the US 71st Infantry Regiment to San Juan Hill, pictured as they marched up the Camino Real. The observation balloon is visible ahead of them. Drawing by Charles J. Post of the 71st NY Infantry. (Charles J. Post Collection)

The British Capt. Lee watched the American troops attack the Spanish blockhouse in the final assault on the village perimeter. Turning to an American officer, he asked: ‘Is it customary with you to assault blockhouses and rifle pits before they have been searched by artillery?’ ‘Not always’ was the embarrassed reply. A thoroughly profossional defence had been overcome by weight of numbers and bravado. Lack of planning, reconnaissance and experience on the part of Gen. Lawton and Gen. Shafter caused needless American casualties in what was the bloodiest engagement of the campaign. American losses were 81 men killed, including four officers. A further 360 were wounded and the subsequent lack of medical attention meant that many wounds would prove fatal. In fact, around 10 per cent of the effective strength of Lawton’s division was lost in what was meant to be a simple clearing operation. Vara del Rey also achieved his goal of preventing Lawton’s troops from reinforcing Shafter. After a somewhat half-hearted probe at dusk towards the Ducrot House and Santiago. Lawton decided not to risk his bloodied division in a night attack in unfamiliar terrain. He simply retraced his steps back to Marianage and El Pozo and did not reach San Juan Heights until just before noon on the following day. A Spanish officer said of the action: ‘the Americans it must be acknowledged, fought that day with truly admirable courage and spirit … but they met heroes’.

GRIMES’S BATTERY OPENING FIRE ON THE SPANISH BLOCKHOUSE

At 8:20am on the morning of 1 July 1898, the battery on El Pozo Hill shattered the silence by starting its bombardment of the Spanish blockhouse on the neighbouring San Juan Hill. The Spanish quickly replied with counter-battery fire, killing a number of troops passing along the road near the American battery position. A cluster of foreign military observers, staff officers and war correspondents who were watching the bombardment also hastily ran for cover: it was an almost comic start to what would be a bloody day. The battery was armed with four 3.2 in. Quick Firing Field Guns, considered obsolete by most foreign observers. They used black-powder cartridges to propel their shells, and these produced thick clouds of smoke, which betrayed the gun position to the Spanish. Spanish artillery pieces used smokeless powder, which reduced the chances of effective counter-battery fire. The bombardment was fired at a range of just over a mile, and lasted approximately 30 minutes. The fourth round fired hit the roof of the blockhouse, and after that the bombardment was on target and effective, despite the obvious obsolescence of the guns. A Lack of ammunition prevented the battery continuing the action, a supply error typical of the logistical difficulties that dogged the campaign.

The observation balloon that drew heavy Spanish rifle fire onto the troops strung out below it on the road leading to Bloody Ford: it was later shot down there. (National Archives)

At around 4:00am, the main army stirred itself and prepared a breakfast of hardtack and coffee. Frederic Remington, the artist, watched the horses of Grimes’s four-gun battery pull the guns onto El Pozo Hill, from where they could shell the Heights. The rest of the army, backed up on the Sevilla road, prepared to march into battle. As Pvt. Post of the 71st New York Volunteer Regiment advanced, he heard Capron’s guns open up on El Caney, four miles to the north, and ‘for the first time it dawned on us that there might be fighting ahead’. His regiment passed the mounted figures of William Randolph Hearst and New York Journal correspondent James Creelman, who were watching the troops. ‘Hey Willie!’ cried the troops. ‘Good luck!’ responded the news magnate who had done more than anyone else to start the war that was about to reach its climax; ‘Boys, good luck be with you.’

Gen. Kent arrived on El Pozo Hill just as Grimes’s battery was deploying, watched by a crowd of staff officers, military attaches and journalists. Lt.Col. McClerland briefed him and showed him the Heights. On the left of the main ridge, marked on the map as ‘San Juan Hill’, sat a blockhouse with a red tile roof. Once his column reached the meadow he was to deploy to the left of the road, then attack it. Gen. Sumner’s dismounted cavalry would deploy to the right of the road, attack the outlying Kettle Hill, then the main ridge of San Juan Heights behind it. As he waited for the battle to start Kent chatted to Maj. John Jacob Astor, staff officer and multi-millionaire. The El Caney action had been raging for almost two hours, so it was presumed to be drawing to a close. The frontal assault was timed to coincide with the reinforcements of Lawton’s division arriving from El Caney. Lt.Col. McClerland looked at his watch, decided it was time to start, and ordered Capt. Grimes to open fire. It was almost exactly 8:20am.

Capt. Grimes’s battery on El Pozo Hill pictured opening fire on the Spanish blockhouse on San Juan Hill. The Spanish would return fire within seconds of the photograph being taken. (National Archives)

The first 3.2 in. gun fired amid a cloud of black powder, and its shell overshot the blockhouse: the following two did likewise. With the fourth round, though, the battery found its mark, scoring a hit on the blockhouse roof and raising a cheer from the observers. The newspaper artist Howard Chandler Christy remembered that ‘a shell went through the roof and exploded, covering itself in a reddish smoke and throwing pieces of tile and cement into the air’. The other guns ranged in and bombarded the blockhouse and the surrounding trenches.

Col. Wood turned to Lt.Col. Roosevelt and, eyeing the crowd of onlookers behind the guns, remarked that there would be hell to pay if the Spanish returned fire. As he spoke, two Krupp shells whistled overhead and exploded behind them on El Pozo plantation itself. A chunk of shrapnel hit Roosevelt’s wrist ‘raising a bump about as big as a hickory nut’. Others weren’t as lucky. The salvo landed amongst a huddle of Cuban insurgents and waiting Rough Riders, killing and wounding several soldiers. The observers ran for cover, leaving the gunners to continue their bombardment alone. Grimes fired for another 30 minutes then ceased, awaiting ammunition and orders.

Sumner’s men, followed by those of Kent’s division, continued up the Camino Real. Just past El Pozo, the muddy road narrowed, forcing the men to march two abreast rather than in a column of fours. Continuous halts made the approach march seem interminable, but once within a mile of the San Juan River, the head of the column came under heavy fire. Pvt. Post and the 71st New York Volunteers heard the firecracker popping of the Mausers, and an occasional buzz as a bullet hit a tree. He was under fire at last: ‘I felt a tenseness in my throat, a dryness that was not a thirst, and little chilly surges in my stomach.’

The Spanish were familiar with the terrain, and knew where the road paralleled the Aguadores River as it snaked through the jungle. They had marked the range and fired repeated volleys into the jungle, concentrating on the points where the road crossed streams, which would create bottlenecks. Richard Harding Davis likened the terrain to a place ‘where cattle are chased into the chutes of the Chicago cattle-pen’. Spanish sharpshooters added to the hail of bullets by sniping at the American soldiers from both sides of the trail. To add to the confusion, the Signal Corps had inflated an observation balloon, and, tethered to a wagon, it accompanied the troops as they marched down the trail. It also served as a perfect range marker for the Spanish. ‘Huge, fat, yellow, quivering’, it drew heavy fire, and Maj. Maxwell commanding the balloon detachment quickly became the most unpopular man in the army.

Roosevelt was furious that it was risking the lives of his men. Crossing the San Juan River, he was ordered by McClernand to branch to the right, head upstream, then wait for orders. ‘I promptly hurried my men across, for the fire was getting hot, and the captive balloon to the horror of everybody, was coming down to the ford.’ Frederic Remington reached the river ford and abandoned his horse as the bullets whistled around him. ‘A man came, stooping over, with his arms drawn up, and hands flapping downward at the wrists. That is the way with all people when they are shot through the body, because they want to hold the torso steady, because if they don’t it hurts.’ Lt. John Pershing (‘Black Jack’) of the 10th Cavalry, a ‘Negro’ regiment, remembered reaching the ford just as the bullet-shredded remains of the balloon collapsed into the river to their right. ‘We were posted for a time in the bed of the stream, directly under the balloon, and stood in water to our waists awaiting orders to deploy.’ Gen. Wheeler had risen from his sickbed, and the old Confederate cavalryman sat on his horse in the middle of the river, oblivious to the bullets slapping the water around him. Pershing saluted him as a piece of shrapnel ploughed into the water between them. Wheeler returned the salute and observed that: ‘The shelling seems quite lively’.

As the 71st New York moved towards the ford, Pvt. Post noticed that ‘the trail underfoot was slippery with mud. It was mud made by the blood of the dead and the wounded, for there had been no showers that day. The trail on either side was lined with the feet of fallen men’. Over 400 men were killed and wounded at the ford (renamed ‘the Bloody Ford’) and on the jungle track leading towards it. Apart from the artillery, the troops still hadn’t been able to return the fire. Davis later wrote that ‘Military blunders had brought 7,000 American soldiers into a chute of death’. Troops were log-jammed back up the trail from the ford, and subjected to constant fire. As units filed over the ford and deployed along the edge of its banks, the firing continued unabated, but at least the riverbank provided a small degree of protection from the Spanish rifles. Before it was brought down, the observation balloon had reported that a trail was seen branching off from the Camino Real before the ford and emerging at the river further to the south. Gen. Kent sent the next regiment, which happened to be the 71st, down the new track in an effort to relieve the log-jam. The rest of the army lay in the river bed or along the trail and awaited orders. As Davis recalled: ‘Men gasped on their backs, like fishes in the bottom of a boat … their tongues sticking out and their eyes rolling. All through this the volleys from the rifle pits sputtered and rattled, and the bullets sang continuously like the wind through the rigging in a gale … and still no order came from Gen. Shafter.’ It was now well past noon, and the leading troops had been pinned down in the river bed for over an hour. Roosevelt and the Rough Riders lay to the right of the American line along the bed, facing the Spanish outpost in the refinery on Kettle Hill. Beside them were the other troops of Wood’s brigade (the 1st and 10th Cavalry). As ‘Mauser bullets drove in sheets through the trees’ which lined the bank, Roosevelt sent repeated requests for orders to Wood and Sumner. One of his messengers was even killed in front of him as he waited. Casualties amongst the Rough Riders were mounting, and included Capt. ‘Bucky’ O’Neill, hero of Las Guasimas. Roosevelt recalls that he was about to conclude that in the absence of orders he had better ‘march towards the guns’, when a lieutenant rode up with the ‘welcome command’ to advance and support the regulars in an assault on the hills. This meant a direct attack on Kettle Hill. Roosevelt summed up what happened next in the phrase he called ‘My crowded hour’. It was 1:05pm.

Troops of the US 16th Infantry waiting in the riverbank of the San Juan River for the order to advance. Most US casualties were inflicted during this pause in the battle. (Library of Congress)

The Rough Riders waiting for orders to advance on Kettle Hill. The troops are shown being subjected to heavy fire. This was the period when Capt. ‘Bucky’ O’Neill was killed. Drawing by Frederic Remington. (Frederic Remington Collection)

Roosevelt ordered his regiment forward, noticing that, ‘always, when men have been lying down under cover for some time, and are required to advance, there is a little hesitation’. They passed the prone figures of the regular cavalrymen, who had not yet received orders to advance, and who were positioned in front of the volunteers. Roosevelt announced that ‘the thing to do was to try to rush the entrenchments’, but the regular cavalry officers wanted none of it. ‘Then let my men through, Sir’ responded Roosevelt. As they advanced, the cavalrymen leaped up and joined them. Roosevelt noted to his left: ‘the whole line, tired of waiting, and eager to close with the enemy … slipped the leash at almost the same moment … by this time we were all in the spirit of the thing and greatly excited by the charge, the men cheering and running forward between shots’. In reality, a conference of officers had just decided to order the whole line to advance and messengers had passed down the line. All along the line, regiments picked themselves up and moved ahead.

The blockhouse on San Juan Hill, seen from the Bloody Ford. Parker’s Gatling guns took up a position 50 yards forward of the camera position when they opened fire on the Spanish blockhouse. (National Archives)

View from the barbed wire at the foot of Kettle Hill, looking towards the Rough Riders’ positions along the San Juan River. Roosevelt charged from the trees, past the camera and up the hill beyond. The Buffalo Soldiers were deployed in the grass in front of the tree line. (National Archives)

At Kettle Hill, elements of the three cavalry regiments of Wood’s brigade scrambled over a barbed wire fence and charged up the hill towards the refinery, now only 300 yards away. To the right of the line, the Rough Riders were the first to charge. They were joined by the 10th and then the 1st Cavalry, flanked on their left by the 9th, followed by the 6th and the 3rd Cavalry regiments. The first wave therefore consisted of Buffalo Soldiers and Rough Riders. An officer ordered the troops to dress ranks on the colours, but it was too late to establish an orderly line as the volunteers threw discipline to the wind and charged headlong up the hill. All the regulars could do was to join them. A dip protected the troops from the worst of the Spanish fire until they reached the military crest about 100 yards from the Spanish rifle pits. A military attaché turned to Steven Crane, who was watching from the river, saying; ‘It’s plucky you know! By Gawd it’s plucky! But they can’t do it!’ Davis saw that: ‘There were so few of them. One’s instinct was to call to them to come back. You felt that someone had blundered and that these few men were blindly following out some madman’s mad order’. Further to the left, Crane watched the men of Hawkins’ brigade charge towards the blockhouse. Someone yelled: ‘By God, there go our boys up the hill! … Yes, up the hill … It was the best moment of anybody’s life!’ There was no turning back now.

On his horse Texas, Roosevelt galloped ahead of his men towards the refinery buildings at the top of Kettle Hill, but 40 yards from the crest, Texas ran into a second barbed wire fence and was wounded. The two cavalry brigades were intermingled by now. The guidon bearer of the 3rd Cavalry fell, and a soldier of the 10th took up the flag. Roosevelt dismounted and continued over the wire followed by his orderly, Henry Bardshar. They were now less than 50 yards from the crest. Fortunately for the impetuous Roosevelt, the Spanish were not as resolute as the defenders at El Caney. As the Americans approached, the defenders began abandoning the position and fleeing back down the reverse slope of the hill and up the slope of San Juan Heights beyond. The guidon bearer of the 10th Cavalry planted his standard in the Spanish trench, followed by the standard bearer of the Rough Riders. Following behind, Remington felt the rain of Mauser bullets slacken and heard a cheer. Looking up he saw the Buffalo Soldiers’ flag sticking in the Spanish parapet. American cavalrymen, both black and white, regular and volunteer were crowded together at the top of Kettle Hill, making a perfect target for Spanish marksmen firing from the Heights themselves. Their officers tried to form them into some kind of firing line, and the men returned fire to the west and to the south-west, towards the blockhouse. As the dismounted cavalrymen flopped down on the crest of Kettle Hill, they had a perfect view of the assault on San Juan Hill.

In front of Gen. Kent’s division crouched in the river bed was a line of trees, from which a barbed wire fence was strung. Beyond it lay 300 yards of open meadow, between the river and the foot of the Heights. The Americans tried to return the Spanish fire, but with little effect: the Spanish were too well dug in. The only way to dislodge them was by a frontal assault: in fact, faced with this prospect, the Spanish had reinforced their position. The troops on the Heights were from the 1st Provisional Battalion of Puerto Rico. They were joined by troops from the 1st Talavera Peninsular Battalion, as well as volunteers from the city. Gen. Linares himself joined his troops in the front line, near the blockhouse. Around 1,000 Spanish soldiers and two guns now waited on the Heights. The weight of fire from the Spanish positions was taking its toll and American casualties were mounting: among these was Col. Wikoff, commanding Kent’s 3rd Brigade. Two regimental commanders were also killed as they waited at the riverbank. Aides rode back to Shafter to try to get him to order an advance, but no message ever reached the front line. The decision to advance would have to be made by the men on the spot. A group of officers waited for orders on the Camino Real, above the Bloody Ford. Gen. Sumner, Gen. Kent, several brigadiers and Lt. Miley, Gen. Shafter’s aide, held an impromptu conference. In the end it was the lieutenant as Shafter’s representative who made the decision. Shortly after 1.00pm, he declared that: ‘the Heights must be taken at all costs’. The meeting broke up and couriers raced to take the message to attack to the waiting regimental commanders.

Lt. Parker’s Gatling guns firing in support of the attack up San Juan Hill. Their fire support was the turning point of the battle. Drawing by Charles J. Post of the 71st NY Infantry. (Charles J. Post Collection)

The principal Spanish defensive line before Santiago was along the ridge of San Juan Heights. The anchor was the blockhouse near its southern end, and this would be the focus of the American attack when it came. The ridge was protected by a forward position on Kettle Hill, and by lines of barbed wire on its eastern approaches. In the jungle beyond the San Juan River, Spanish sharpshooters were poised to snipe at the advancing Americans. Gen. Linares and Spanish reinforcements were sited a half-mile to the rear at Fort Canovar. As Grimes’s battery opened fire on the blockhouse at 8:20am, the head of the column was passing El Pozo Hill. It soon came under heavy Spanish fire, and an accompanying observation balloon only served to give the Spanish a ranging marker. As the Cavalry Division reached Bloody Ford it deployed to the north-east, along the bank of the San Juan River. Kent’s division deployed to the left, facing the blockhouse. The troops would now wait under constant fire while they waited for orders to attack.

The attack on the San Juan blockhouse, a rare photo taken by a man accompanying Hawkins’ brigade. The ascending infantry can just be made out on the right. (National Archives)

The San Juan blockhouse and ruined barrack outbuildings, pictured after the battle. This was the linchpin of the Spanish position on San Juan Heights. (National Archives)

The attack on the Heights started in the centre of the American line, where Gen. Hawkins and his brigade faced the Spanish blockhouse, to the left of the Camino Real. Once over the fence and out of the tree line along the river the ground was flat for 300 yards before the base of the Heights rose out of the valley floor. As the line advanced, it came under heavy fire, and was pinned down in the long grass of the valley floor. Further down the line, most of the troops were still in the tree line along the river or in the jungle behind it. At around 1.15pm, the attackers heard a drumming sound, ‘like a coffee grinder’. Fear of Spanish machine guns was replaced by elation, when the Americans worked out that the sound came from their own Gatling guns. Lt. Parker and his four Gatlings had taken up a position in front of the Bloody Ford and opened up a heavy suppressive fire on the Spanish positions around the blockhouse. At a range of just under 700 yards, the Gatlings fired for eight minutes, and thousands of rounds swept over the Spanish positions. This fire proved to be the decisive moment of the battle. At around 1.20pm, as the Gatlings and fire from Kettle Hill pinned down the Spanish defenders on the Heights, Lt. Jules G. Ord of the 6th Infantry jumped to his feet, yelling: ‘Come on! We can’t stop here!’ The rest of Hawkins’ brigade resumed the attack, spearheaded by the 6th and 16th Infantry regiments. Once at the foot of the Heights, they discovered that the Spanish had committed a cardinal military sin: they had dug their trenches on the topographical crest of the Heights, and not the ‘military crest’. The ‘military crest’ is a line below the actual crest which offers the defenders an unrestricted field of fire all the way to the base of the hill. By lining the topographical crest, the Spanish created ‘dead ground’ for most of the way up the hill, where the topography shielded the attackers from Spanish bullets. Once at the base of the hill, the attackers would be safe until they approached the top. As the troops reached the top, the supporting fire from Kettle Hill and the Gatlings ceased, and at around 1.28pm, the Americans reached the Spanish trenches. The Gatling fire had broken the resolve of the defenders, and most were fleeing back towards Santiago. A few fought on, and Lt. Ord was killed on the parapet of the Spanish trench. Within a few minutes it was all over, and the blockhouse was in American hands.

Richard Harding Davis watched the troops storm the hill. ‘They had no glittering bayonets, they were not massed in regular array. There were a few men in advance, bunched together and creeping up a steep, sunny hill, the top of which roared and crashed with flame … Behind the first few, spread out like a fan, were single lines of men, slipping and scrambling in the smooth grass, moving with difficulty … a thin blue line that kept creeping higher and higher up the hill.’

THE CHARGE OF THE ROUGH RIDERS UP KETTLE HILL

The image that endured in public imagination from the campaign was the charge of Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders up San Juan Hill. In reality, although the event was a crucial element of the American victory, it formed only one part of a larger engagement. Instead of San Juan Hill, the Rough Riders charged up Kettle Hill, a smaller feature in front of San Juan Heights. San Juan Hill was the name given to the end of the Heights where the Spanish blockhouse was sited. Also, although Roosevelt and the Rough Riders initiated the charge up Kettle Hill, they were accompanied by elements of several other regiments, most notably the Buffalo Soldiers of the 9th and 10th (‘Negro’) US Cavalry Regiments. Contrary to many popular depictions, all the cavalrymen charged up the hill on foot. The only mounted figures were a handful of officers, including Roosevelt himself, who was on his horse Texas. The charge was carried out almost simultaneously along the whole American front line, with the Rough Riders on the right flank of the advance. Where the main attack on the Heights was temporarily stalled, the cavalrymen took Kettle Hill in the first assault. Roosevelt was a consummate politician, and the correspondents he courted so carefully highlighted his obvious courage in such a way that he became the linchpin of the battle. This undoubtedly also helped his future electoral prospects.

When Gen. Sumner and Col. Wood reached the top of Kettle Hill, Roosevelt asked for permission to continue the advance to the second objective, the northern spur of San Juan Heights. Sumner agreed, and Roosevelt led the jumbled bulk of several cavalry regiments now on the hill down the other side. Around 800 cavalrymen charged for a second time, as the remainder of the division on Kettle Hill fired in support. As was the case with the blockhouse, this supporting fire was crucial in pinning down the heavily outnumbered defenders. In this section of the Spanish line, barely 200 men faced 2,000 American cavalrymen. The attackers moved around the sides of a small lake, and swarmed up the steep slope on the other side. Fortunately, this sector of the Heights was sparsely defended, and the slope was too steep to let the Spaniards fire on the cavalrymen until they reached their trenches. At that point most of the Spanish decided that they were hopelessly outnumbered and retreated back towards Santiago. A handful remained to contest the crest. Two fired on Roosevelt from ten yards away but missed. ‘I closed in and fired twice, missing the first and killing the second. My revolver was from the sunken battleship Maine … Most of the fallen had little holes in their heads from which their brains were oozing.’ Capt. Lee and Lt.Col. Roosevelt had both observed the same phenomenon: the Spanish heads exposed above the rifle pits were the only target for the American infantrymen, so head wounds were the predominant form of injury. It also attested to the accuracy of the Krag rifle.

The charge up San Juan Hill; a stylised version, one of many to appear in American publications (many of the artists commissioned to produce these were not even present). Drawing by William J. Glackens. From McClure’s Magazine, October 1898. (Monroe County Public Library)

The death of Lt. Ord, as US troops reach the Spanish breastworks on San Juan Hill. Drawing by Charles J. Post of the 71st NY Infantry. It was Ord who precipitated the final charge. (Charles J. Post Collection)

The cavalrymen dug in on the crest. Gen. Sumner brought up the remainder of the division and strung it out along the ridge to the left and right of Roosevelt’s position. A Spanish counterattack was expected, and the exhausted troopers were in no fit state to meet it. An hour later, Sumner, Wood and Roosevelt were joined in the former Spanish trenches by a group of journalists, including Stephen Crane, Frederic Remington and Richard Harding Davis. Together they peered over the crest towards Santiago. Spanish rifle and artillery fire still swept the ridge, and the situation seemed precarious. Crane, seemingly impervious, walked along the crest, smoking a pipe. Davis yelled: ‘You’re not impressing anyone by doing that, Crane’, and stung by the insinuation of being a poseur, Crane returned to the trench. Conditions were still desperate and the line was thinly held. As Harding noted: ‘They were seldom more than a company at any one spot, and there were bare spaces from 100 to 200 yards apart held by only a dozen men. The position was painfully reminiscent of Humpty-Dumpty on the wall.’ As night fell, the Americans felt as if they were clinging to the ridge by their fingernails.

The rear of San Juan Hill, seen from the crest of Kettle Hill in a photo taken after the battle. The San Juan blockhouse is on the left edge of the crest. The Cavalry Division later set up camp on this reverse slope, to reduce casualties from stray Spanish fire. (National Archives)

The climax of the Santiago campaign, this short action sealed the fate of the city and of the Spanish naval squadron sheltering in its harbour. ‘Teddy’ Roosevelt later described the events following his receipt of the order to charge as ‘My crowded hour’.

The San Juan blockhouse pictured soon after its capture. The damage caused by the barrage from Grimes’s and Parker’s batteries is clearly seen. Drawing by Charles J. Post of the 71st NY Infantry. (Charles J. Post Collection)

Casualties were heavy. In the battles at El Caney and San Juan, the Americans lost over 200 men killed, and over 1,100 wounded. 125 of those killed had died at San Juan. These losses amounted to about 10 per cent of the total force available to Gen. Shafter. The Spanish lost 215 killed and 375 wounded most of whom became prisoners of war. Gen. Linares was wounded in the action, and Gen. Toral, who assumed command of the defenders, was unable to organise a counterattack. In the end, it slowly dawned on everyone that the Americans had gained an enormous strategic advantage. When Lawton’s men joined the defenders the next day, and helped secure the American positions, the chance for the Spanish to launch a successful counterattack evaporated. Once heavy guns could be brought up, the Americans could fire on the town below them. More importantly, the Spanish squadron whose arrival in Santiago had been the cause of the war, would also lie at the mercy of the American guns. That night, Admiral Cervera recalled the 1,000 sailors he had landed to bolster the defences of the city. He had a choice; either to try to run from the American blockade – or remain in the harbour and be sunk.

‘Teddy’ Roosevelt and the Rough Riders pictured on San Juan Heights in the days after the battle. This classic photograph by William Dinwiddie is the most widely recognised image of the war. (Library of Congress)

The battleship USS Oregon, pictured in her pre-war white paint scheme. She joined her sister ships the Indiana and Massachusetts at Key West in time to participate in the campaign after a marathon voyage from the US Pacific coast. (Library of Congress)