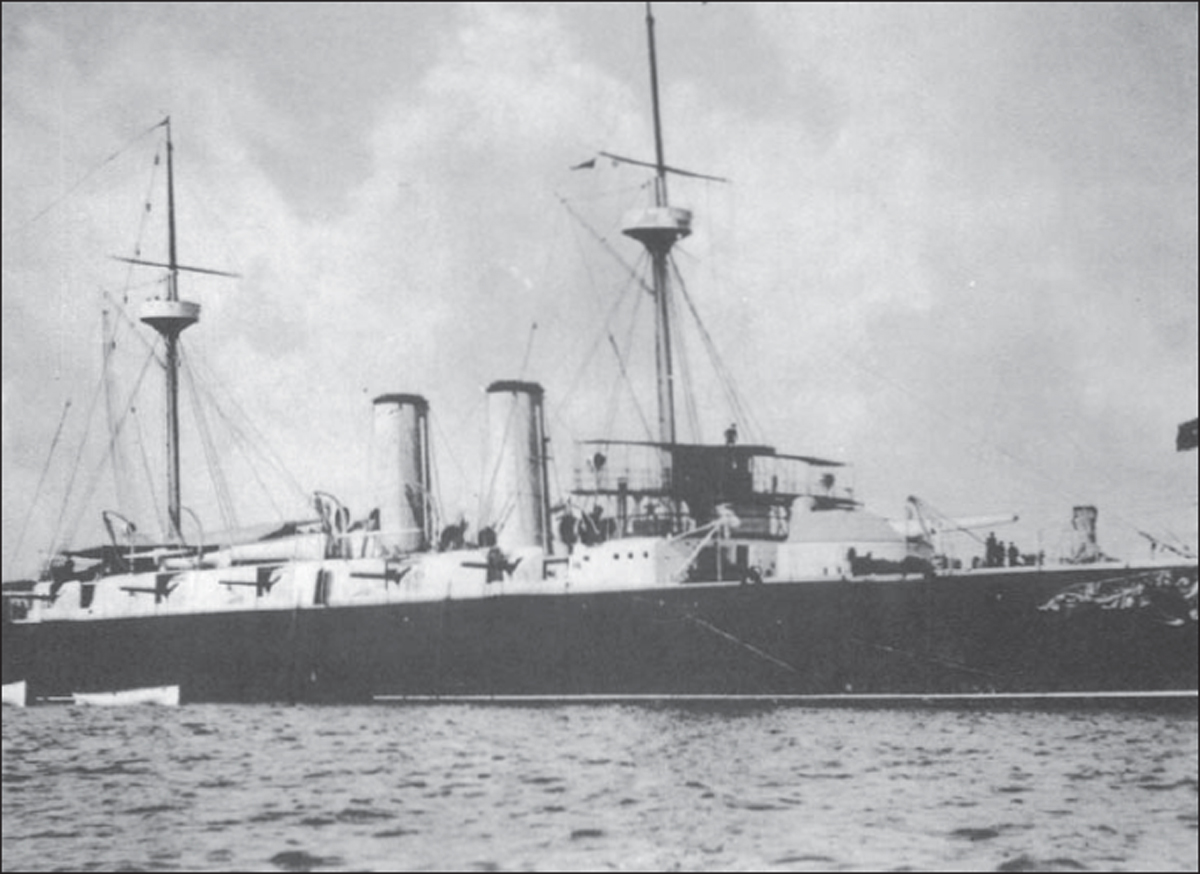

After San Juan Hill was captured on 1 July 1898, the Spanish options were limited. To remain in harbour was to risk being destroyed at anchor by army artillery batteries: to try to break through the American blockade was to invite certain destruction. The four Spanish cruisers and two destroyers were also in poor shape. The Cristobal Colon lacked her main armament, the Vizcaya had a fouled bottom, and both she and the Almirante Oquendo had a number of inoperable secondary guns. Also, 80 per cent of the ammunition carried was defective. If the badly prepared Spanish cruisers took on the larger force of American battleships, they would be destroyed. The Spanish hoped to use the flagship cruiser, Infanta Maria Teresa, to ram the fastest American cruiser, USS Brooklyn, and then in the confusion the remaining Spanish ships could make good their escape to the west.

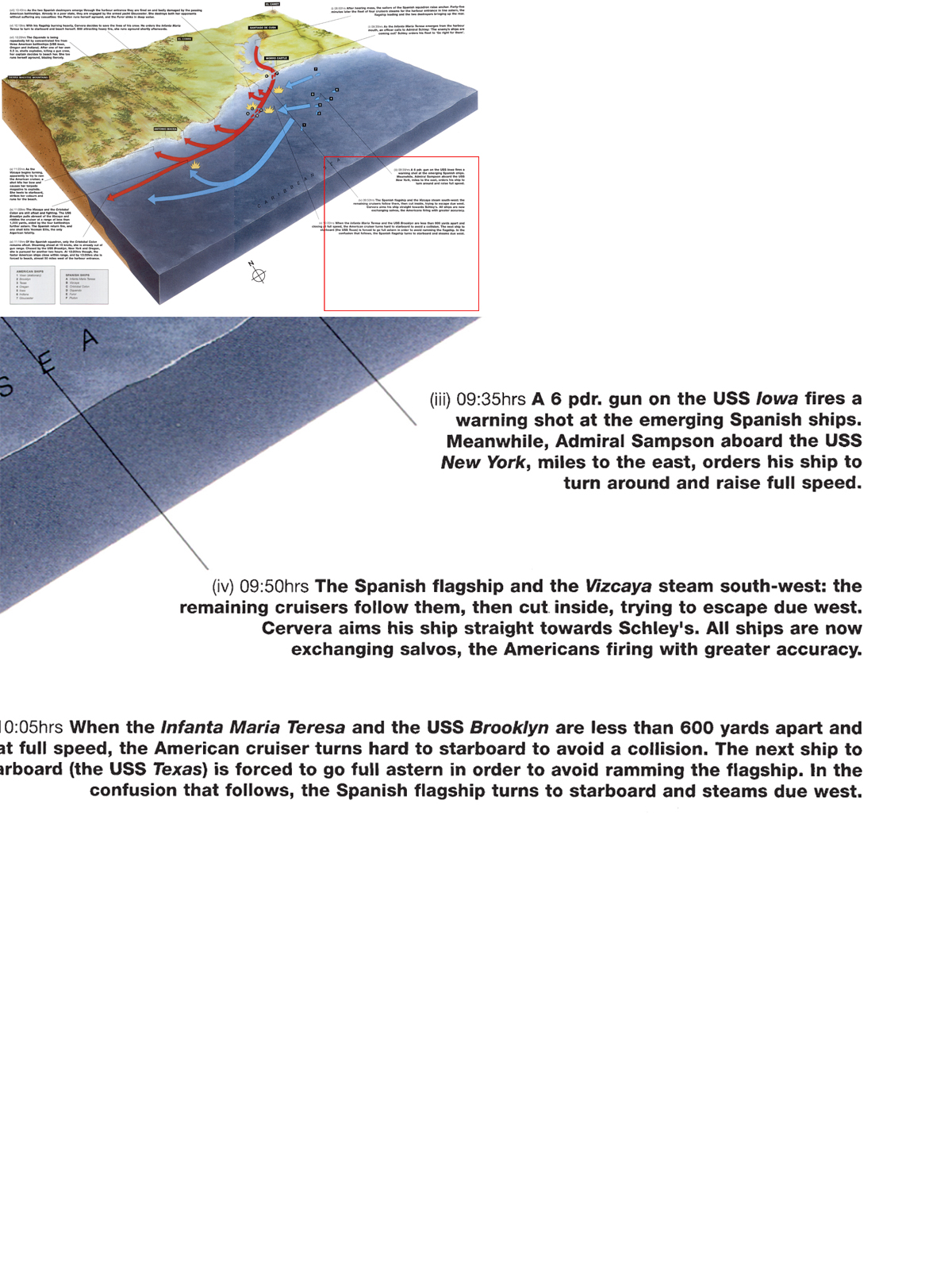

The Spanish naval squadron of four cruisers and two destroyers had brought the war to Santiago by sheltering in the port. The capture of San Juan Heights made its destruction inevitable if it remained there. Admiral Cervera decided to sortie, attempting to run through the US naval blockade. Admiral Sampson in the New York was several miles to the east when the Spanish emerged, and he spent the morning trying to catch up with the battle. Admiral Schley ordered the American ships to close in and give chase. A heavy exchange of salvoes began, and the heavier and more accurate American guns began to find their targets. One by one the Spanish cruisers were hit repeatedly, then forced to run for the shore and beach themselves. By 11:30am only the Cristobal Colon remained afloat: it would be chased for another two hours before sharing the fate of its consorts.

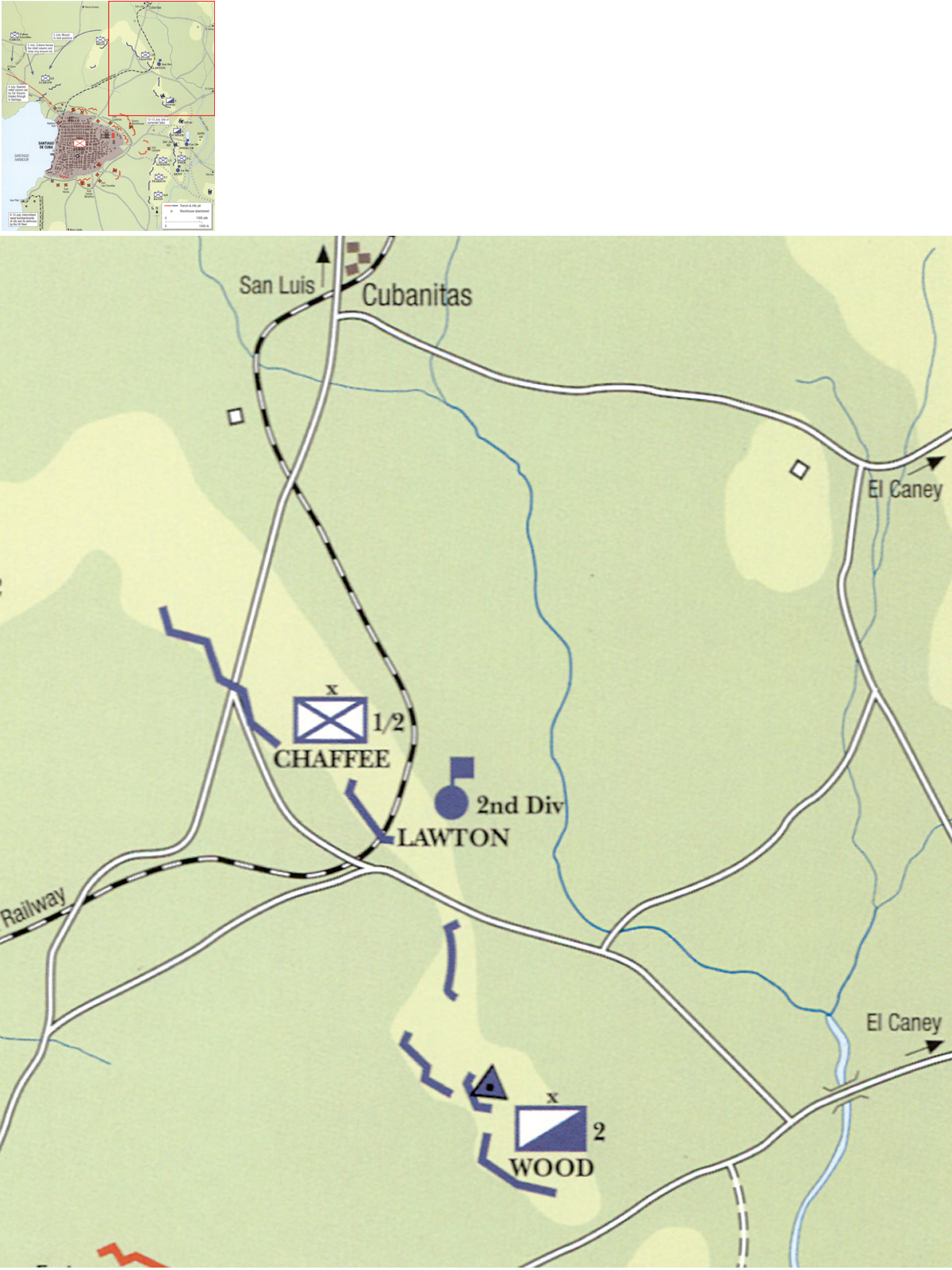

After the battle of 1 July, Shafter was unsure whether he could hold his positions. With the arrival of Lawton’s missing division and at the insistence of Gen. Wheeler, he elected to remain on the ridge. Kent’s division deployed to the left of the main section of San Juan Heights, and Lawton’s division was placed to the north and north-west. The Cavalry Division held the main ridge. After the Spanish fleet was destroyed on 3 July, a Spanish column fought its way through from the west to reinforce the defenders. The Cuban insurgents deployed in that sector had failed to prevent the column reaching the city. Shafter therefore ordered Ludlow’s brigade into a position where it would seal the escape route. Trapped and cut off from their water supply, the Spanish were forced to choose between starvation and capitulation. After a series of temporary armistices and naval bombardments, the Spanish agreed to discuss surrender terms on 12 July.

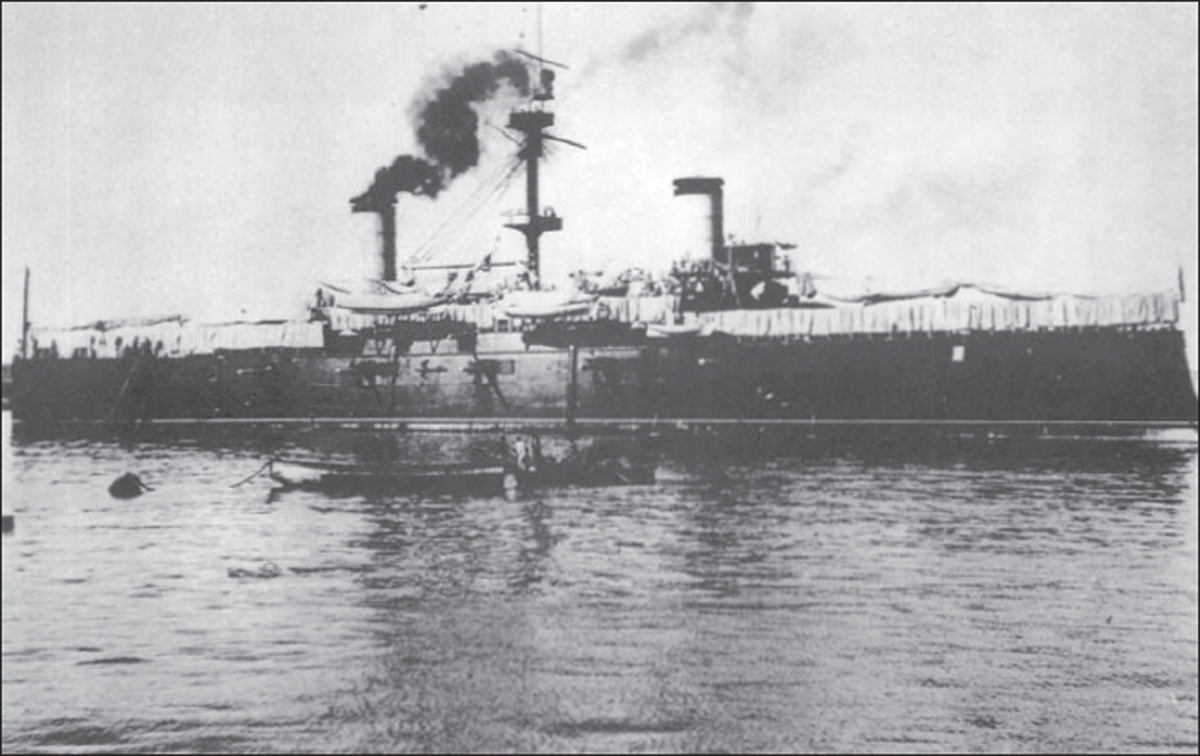

The Spanish cruiser Infanta Maria Teresa, the flagship of Rear-Admiral Cervera. Her performance at the battle was superb, and Cervera planned to sacrifice her in order to allow the rest of the fleet to escape. (US navy)

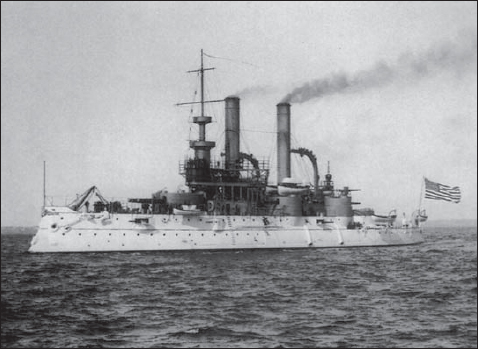

The Spanish cruiser Cristobal Colon. The laundry obscures the empty gun turrets designed to hold her main armament. The ship, built in Italy, was so new that she sailed with only her secondary armament installed. (US navy)

The battleship USS Iowa. Her distinctive high funnels designed to improve boiler performance made her easily recognisable. (Library of Congress)

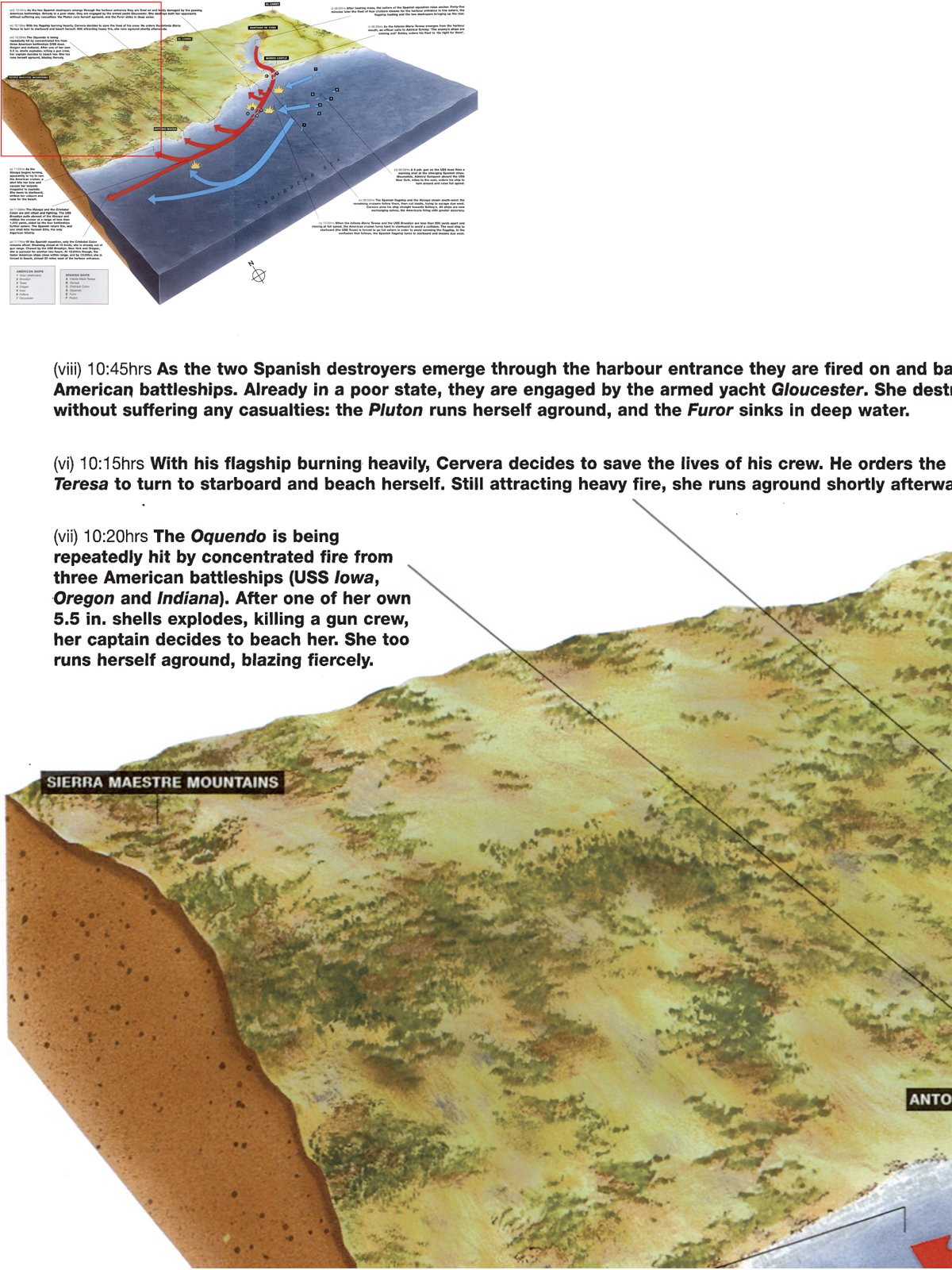

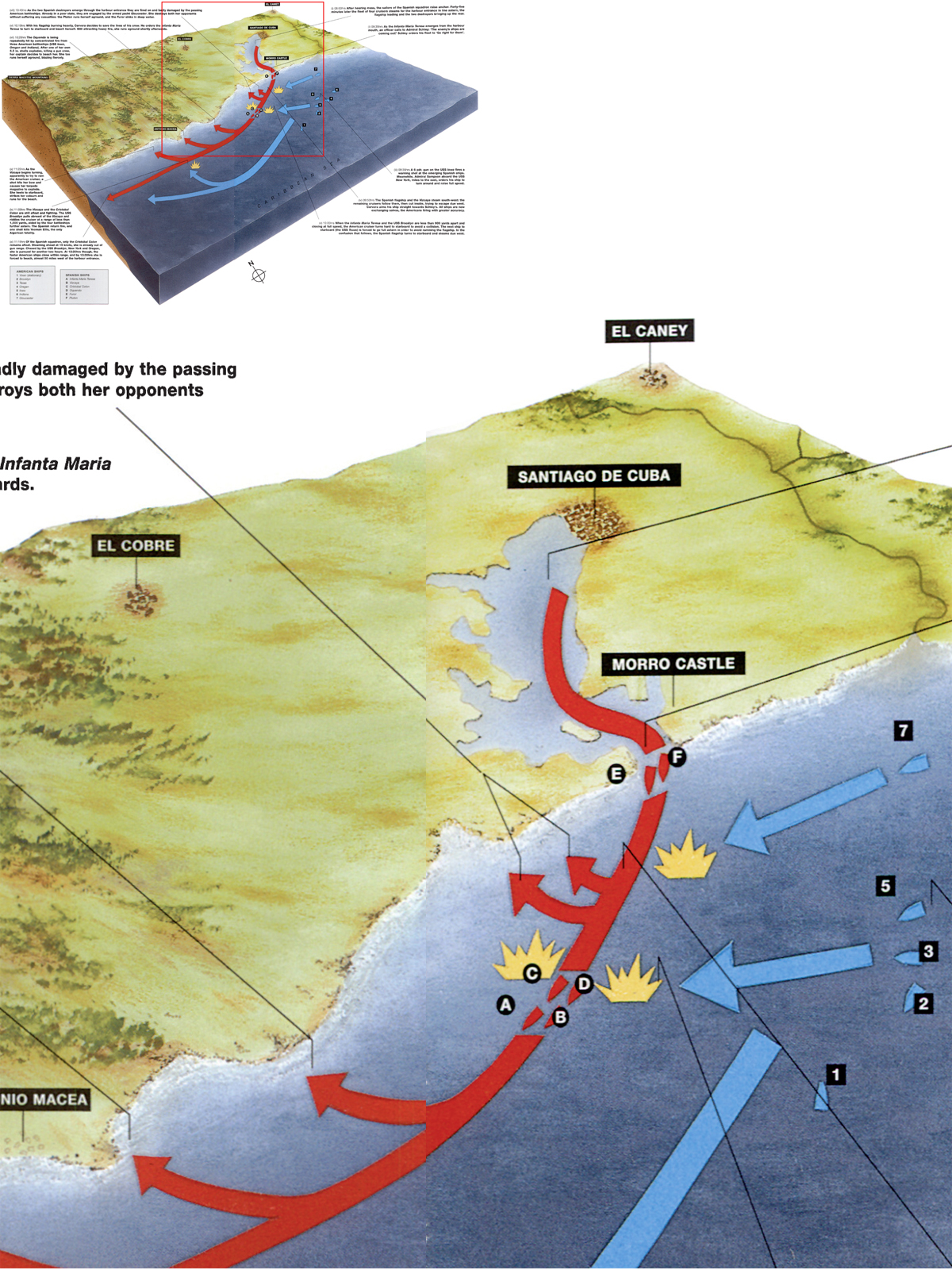

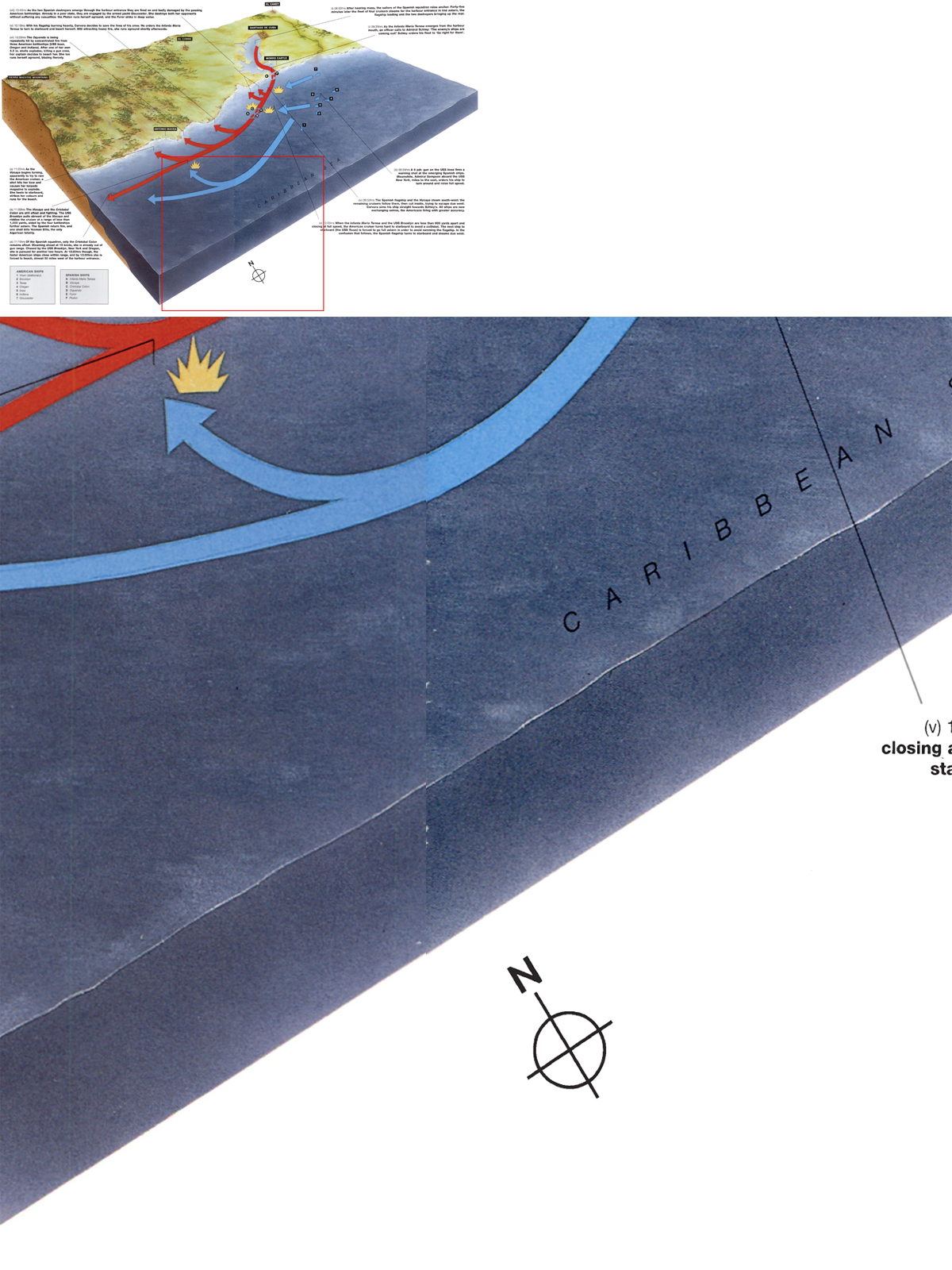

Mass was held at dawn on 3 July 1898, and at 8:00am the small Spanish fleet weighed anchor. Observers on the shore noted that one battleship and Admiral Sampson’s flagship were no longer on blockade but were several miles to the west. This would increase the Spanish chances of escape, but the odds were still suicidal. At 8:45am, the flagship hoisted the signals ‘Sortie in the prescribed order’ and ‘Viva España!’ and led the way towards the harbour entrance. As they got underway the Admiral’s aide was heard to exclaim: ‘Pobre España!’ (Poor Spain!)

At 9:35am, American lookouts spotted the ships emerging in line from the harbour, and alarm bells rang throughout the fleet. Admiral Sampson in the cruiser USS New York was about five miles to the east when the Spanish fleet sortied, so Rear-Admiral Schley was the officer in charge. Confirming that Sampson was nowhere in sight, Schley in the USS Brooklyn gave the order to open fire, and to steam towards the enemy, with the words ‘Go right for them!’.

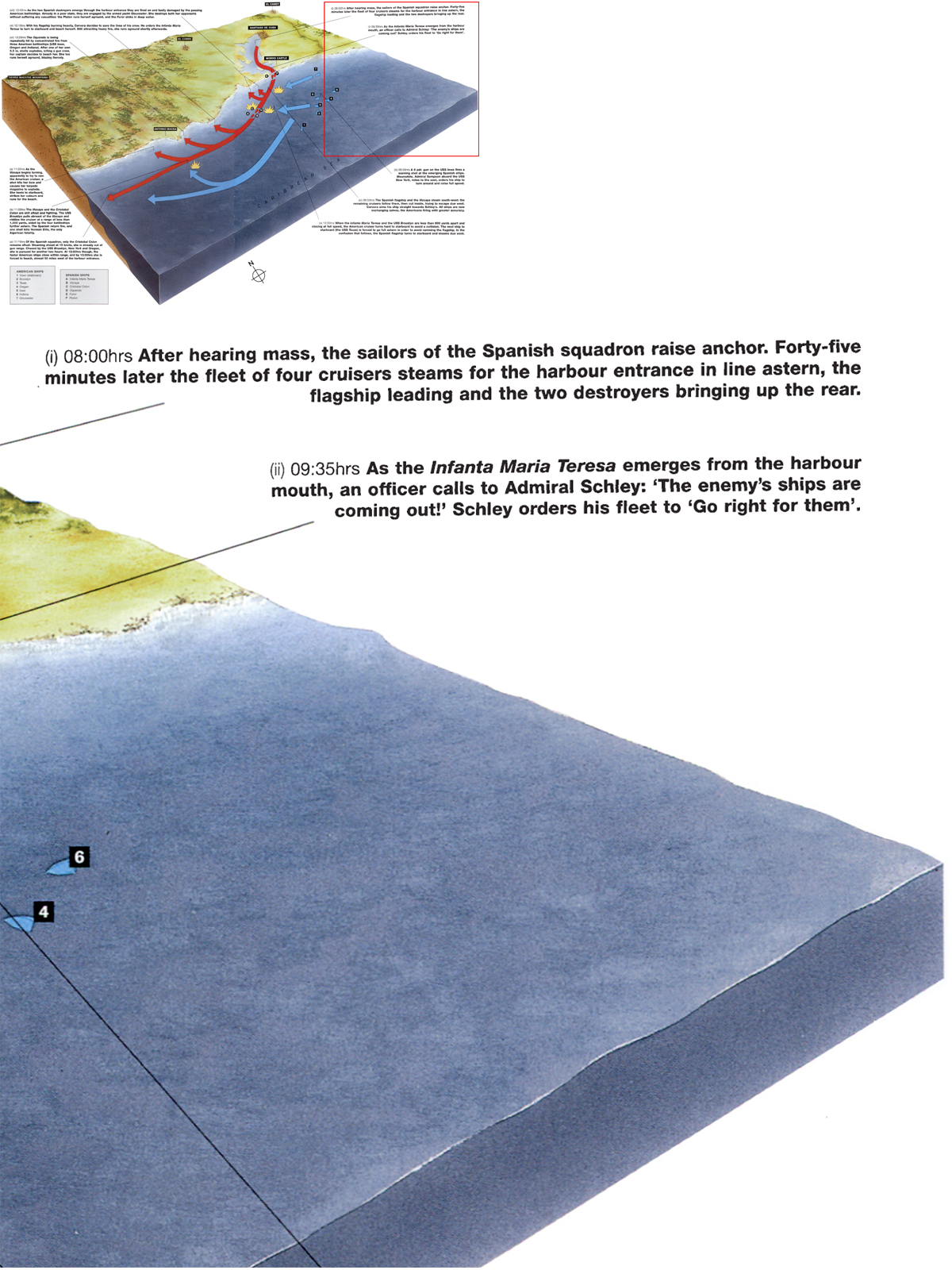

The Spanish speeded up as they emerged from the harbour at six-minute intervals and turned to starboard. The destroyers headed eastward at full speed, while the Infanta Maria Teresa headed straight for Schley’s flagship. The USS Brooklyn realised she was the target of a possible ramming, and when the two flagships were a minute’s steaming apart, the American cruiser turned hard starboard to avoid the Spanish ship. All the other American warships were turning to port to pursue the Spanish, and the Brooklyn turned right into the path of the battleship USS Texas. The battleship’s captain ordered full astern and narrowly avoided a collision, while the USS Brooklyn completed turning in a circle.

By 10:10am, both squadrons were sailing on roughly parallel courses 2,500 yards apart, with the Spanish slightly ahead of most of the American ships. Sampson in the USS New York was steaming full ahead to join the battle. Salvoes crashed around both fleets, but the heavier American guns scored crucial hits. A 13 in. shell from the USS Iowa quickly knocked out the rear turret of the Infanta Maria Teresa. In return, shells from the Cristobal Colon hit the USS Iowa twice, forcing her to reduce speed. By now the concentrated fire of several American warships was raking the Spanish flagship. The Spanish gamble had failed.

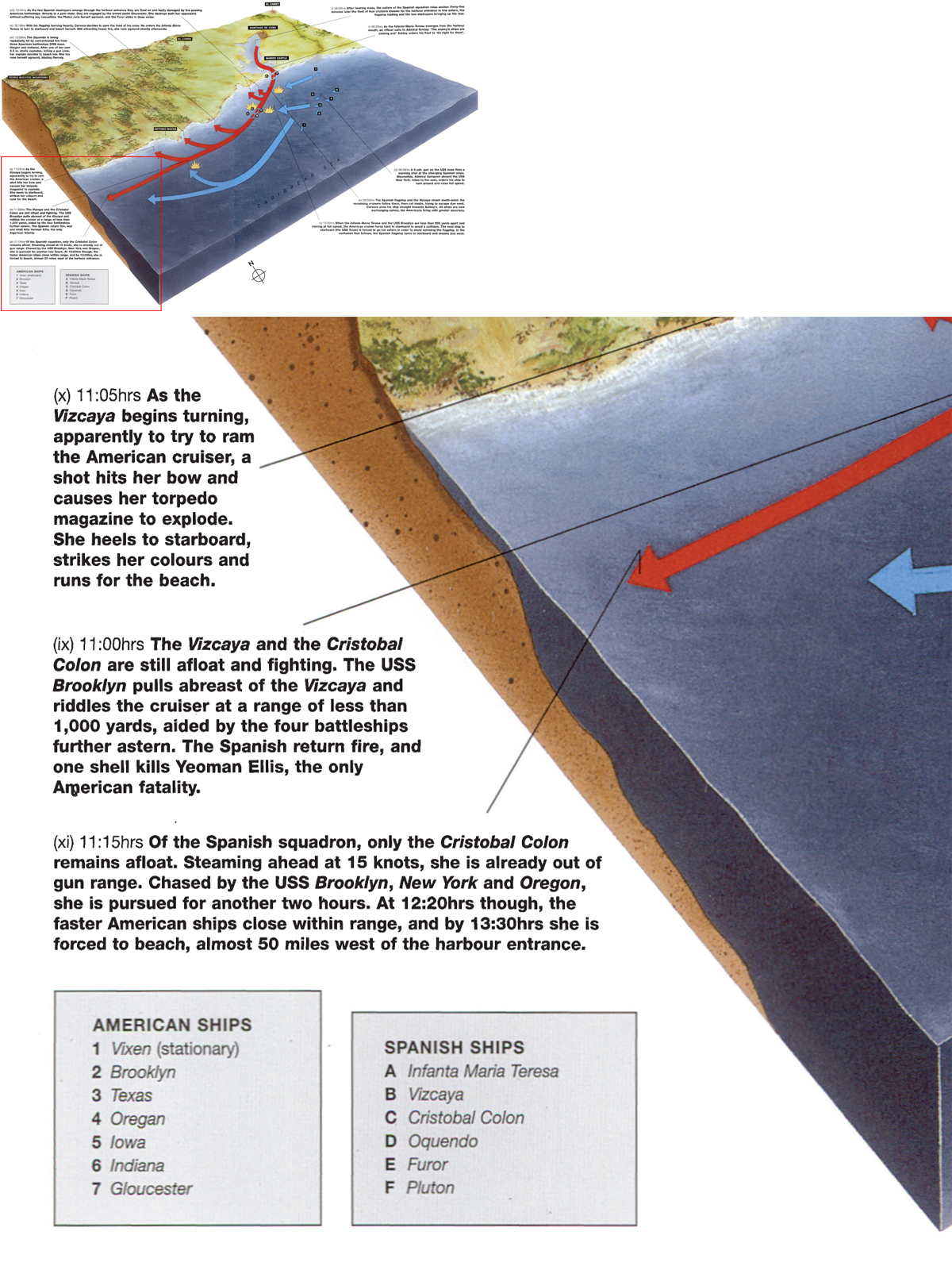

By 10:15am. the Infanta Maria Teresa was blazing from stem to stern. Her magazines flooded, she turned and ran for the beach, and hauled down her colours. The battle had been raging for less than an hour. The Almirante Oquendo was next to go. The rearmost of the four Spanish cruisers, she was fired on repeatedly by three American battleships. As fires threatened to ignite her magazine, she too was run aground onto the beach to the west of the flagship, and surrendered. Only two cruisers now remained.

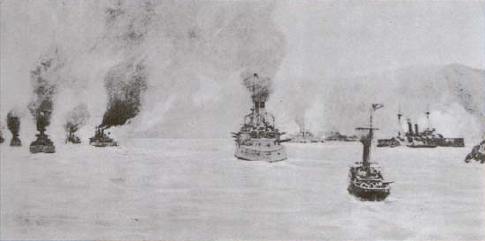

The naval battle of Santiago, as drawn by a war artist on board the USS Indiana. The Spanish ships are to the right of the picture. Drawing by Carlton T. Chapman from Harper’s Weekly, July 1898. (Monroe County Public Library)

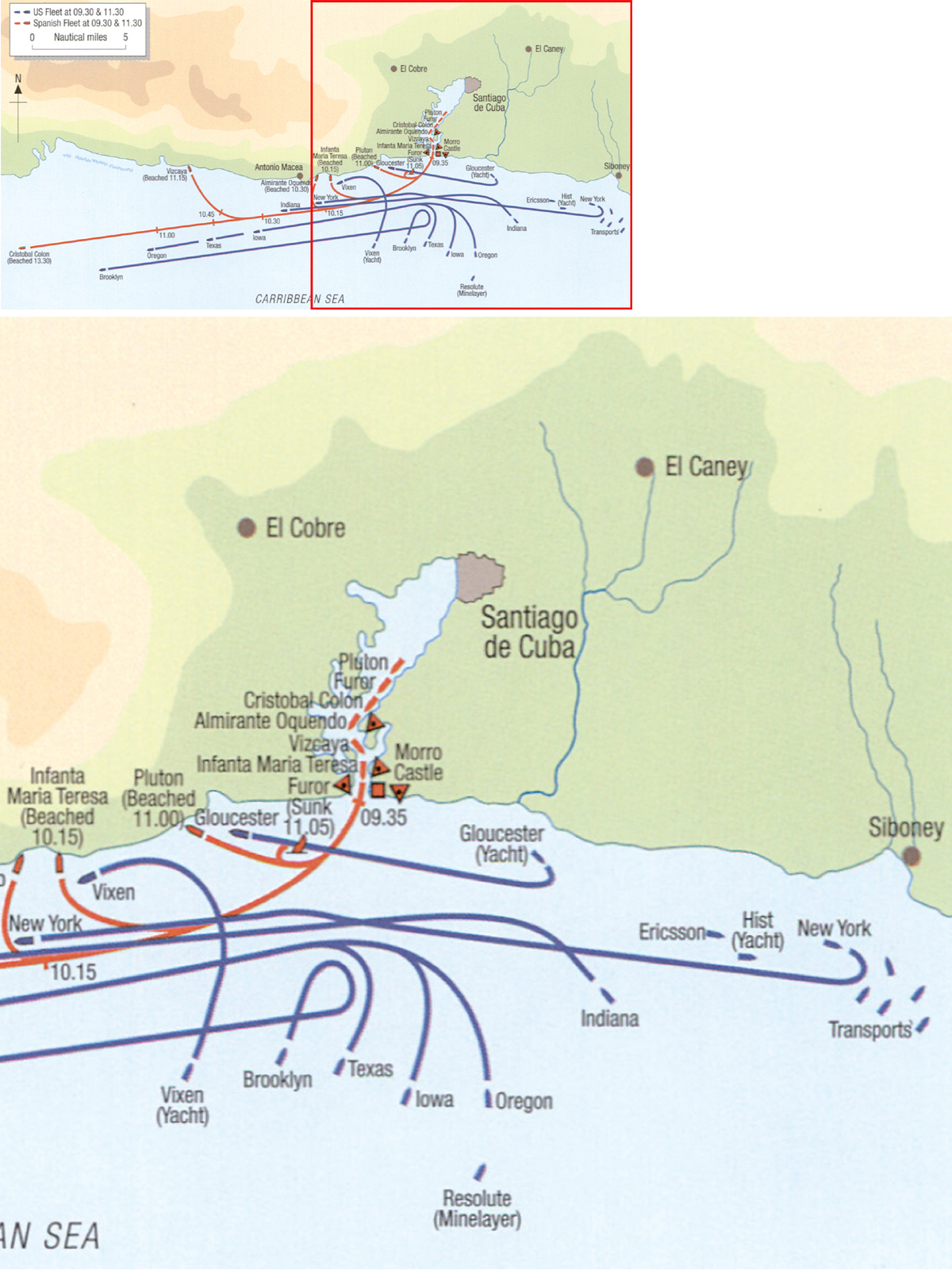

THE SORTIE OF THE SPANISH FLEET AT THE BATTLE OF SANTIAGO

Shortly after 9:30am on the morning of 3 July 1898, lookouts on ships of the American fleet saw their Spanish adversaries emerge from the entrance to Santiago Harbour. The lead ship was the Spanish flagship Infanta Maria Teresa which tried to ram the fastest American ship, USS Brooklyn.

As the other American ships steamed to close with the enemy, the USS Brooklyn turned away in a circle, narrowly avoiding a collision with an American battleship. Both sides started firing, although many of the Spanish shells were defective. As 13 in. shells from the American battleships crashed repeatedly into the Spanish cruisers who were trying to flee at full speed, the action closed to a range of less than a mile. Slugging it out at point-blank range, the Spanish ships got the worst of the exchange, and fire was concentrated on each ship in turn, reducing them to burning hulks. Within an hour of the start of the battle, two Spanish cruisers were aground and burning. The rest of the Spanish squadron would be destroyed within the next hour, with the exception of the cruiser Cristobal Colon. The last of the four cruisers to sortie, she avoided heavy damage and continued her escape to the west. By 1:30pm the pursuing American warships overhauled her, and she too was destroyed.

The Spanish destroyers Furor and Pluton were essentially ignored by the larger cruisers, but had been hit by fire from passing ships. The armed yacht Gloucester finished them off, the Pluton running aground and the Furor sinking in deep water shortly after 11.00am.

The USS Brooklyn closed within 1,000 yards of the slower Vizcaya, and the two slugged it out until a shell detonated the Spanish ship’s bow torpedo tubes: at 11:05am she ran for the beach, racked by fires and secondary explosions. Cheers from the crew of the Texas were cut short by her captain, who yelled: ‘Don’t cheer, boys! Those poor devils are dying.’ The USS Brooklyn and USS Oregon set off after the remaining Cristobal Colon, and after a two-hour chase to the west, she too was forced to beach herself.

The Spanish squadron had been completely annihilated. As the guns fell silent, launches were sent to rescue the Spanish sailors from the sharks, and the Cuban insurgents lining the shore. The gallant Admiral Cervera himself was rescued and taken aboard the USS Iowa where the victors cheered their former adversary. Of the 2,227 Spanish sailors who sailed that morning, 323 had died and the remainder had been either wounded or taken prisoner. Only one American sailor was killed. The victory was complete.

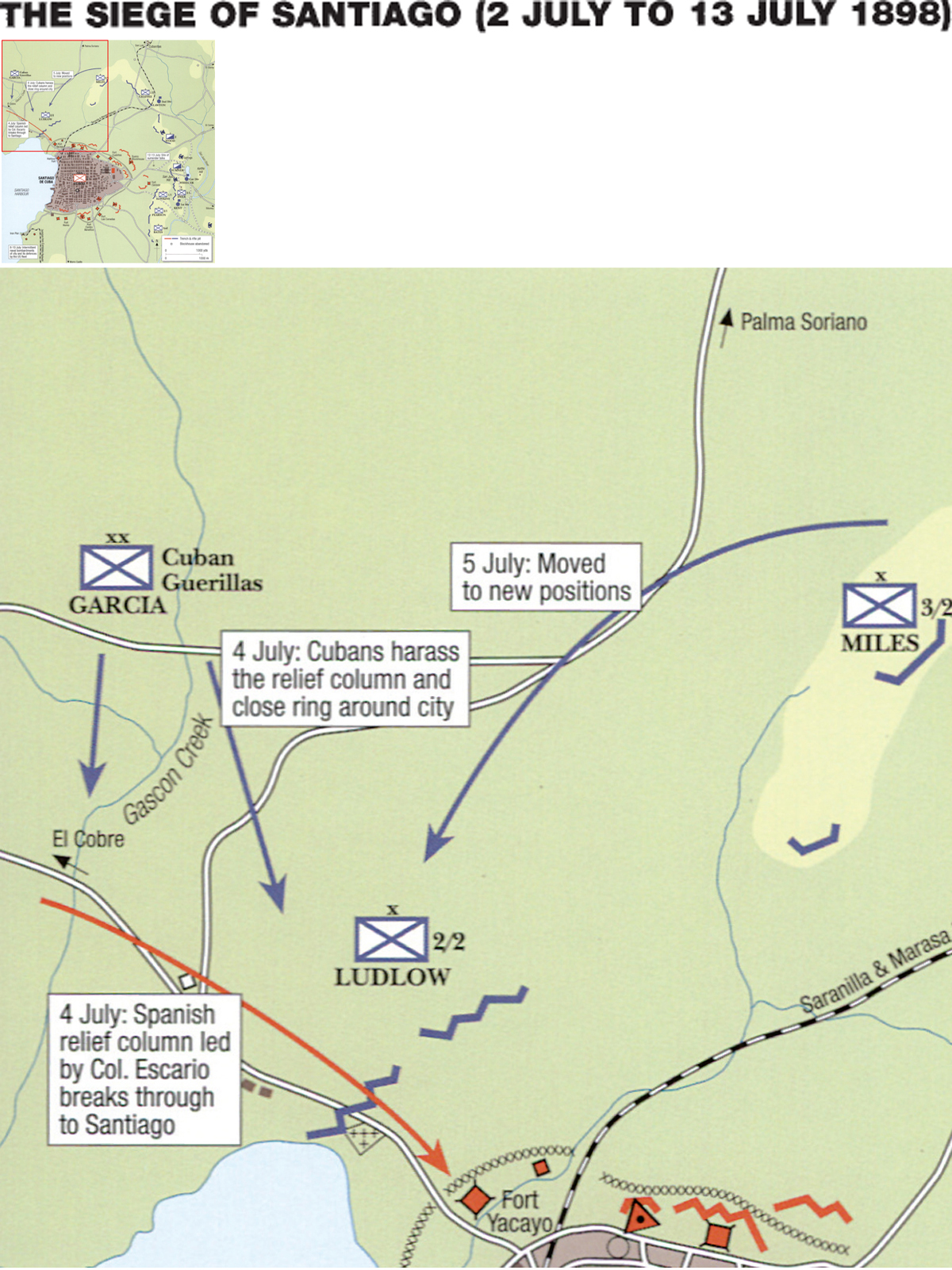

Following the capture of San Juan Heights, the Americans invested Santiago, throwing up fresh entrenchments along the Heights, bringing up Lawton’s Division and placing Garçia’s Cubans to the west of the city. A request to surrender the city was rejected, and after three days of skirmishing, both sides settled down to a siege. Apart from 10,000 Spaniards in the city, another 20,000 were scattered throughout the province, and Shafter was worried they might suddenly appear in his rear, between him and the beachhead.

Although they never materialised, on 3 July a relief column led by Col. Escario fought its way through to Santiago from the west, bringing weary troops and meagre supplies. Toral now had to feed 13,500 troops and 25,000 civilians. On 4 July Shafter and Toral negotiated a four-day truce to allow the evacuation of civilians: over 20,000 left the city, to be housed in a makeshift refugee camp which was established at El Caney. As the American army was on half rations, they could do little more than the Spanish for the hapless civilians. Shafter requested more men and supplies, and his sick list grew daily.

Although life was bad for the Americans, it was unbearable for the Santiago defenders. With their water supply cut off, no food and precious little ammunition, the Spanish position was untenable. Although they held good defensive positions and could resist any American assault, morale was crumbling. On 8 July Toral proposed to surrender if his troops could march away to a nearby town. Although Shafter wanted to accept, the politicians in Washington refused. The siege continued, and naval bombardments caused civilian casualties but few military losses. Shafter offered another truce on 11 July, and proposed to ship the Spanish back to Spain instead of allowing them to walk away. The Spaniards wanted to save face and, with fever casualties mounting, Shafter, now joined by Gen. Miles, wanted a quick resolution of the campaign. After further negotiations between the two generals and Washington and Havana, Toral accepted Shafter’s terms. The Spanish would capitulate: the term ‘surrender’ was to be avoided.

On 13 July the staff officers of both armies met under a large tree between the lines to discuss terms. After a further flurry of international telegrams, on 17 July the Spanish marched out of the city and into captivity. The Spanish surrender came too late to prevent the spread of yellow fever, and by the end of the month over 4,000 soldiers were in hospital. If the Spanish had been able to hold on for another few weeks they might have realised their plan of watching the American army waste away from disease. Roosevelt led the fight in the press corps to have the force recalled, and the War Department capitulated. The troops were recalled, and on 7 August the first ships set sail for home. Reinforcements of ‘Negro’ troops and National Guardsmen from the Deep South were left to garrison Santiago and guard the prisoners, as these troops were apparently less susceptible to fever than the others.

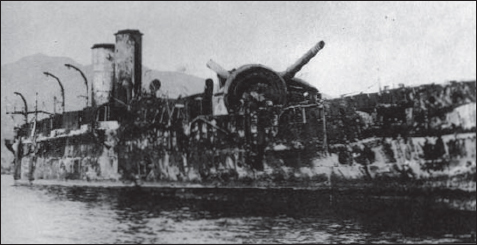

The wreck of the Spanish cruiser Vizcaya on the day after the Battle of Santiago. The fearful damage is evident, as is the effect of the explosion which ripped out her aft turret. (National Archives)

The conclusion of the campaign did not directly bring about the end of the war. 140,000 Spanish troops still remained in Cuba. Gen. Miles launched a virtually bloodless invasion of Puerto Rico during July and August of 1898. The blockade of Cuba continued and plans were redrawn for an assault on Havana. In the Philippines, Manila was captured, and the Pacific islands of Guam and Saipan surrendered without a fight. The Spanish public was increasingly opposed to the continuation of the blood-letting, and on 12 August an armistice was signed. Peace talks continued throughout the year, until the final peace treaty was signed on 10 December 1898. The terms were that the United States would annexe the Philippines, the Pacific Islands and Puerto Rico in return for a compensation fee of $20 million. It would continue to occupy Cuba until independence was granted, and the Spanish army would be repatriated. Despite criticism of imperialism, the US Senate approved the terms. The United States was now a global power.

For Spain, the outcome was an unmitigated disaster. Apart from the loss of prestige, territory and lives, the war had another long-term impact. The army felt let down by the people and politicians, and as a result it became more politicised. This, combined with industrial growth and political instability, helped sow the seeds for the Spanish Civil War (1936–39).

The Americans basked in their new position as a world power, and Hawaii and Panama were soon added to the list of overseas territories. The Spanish American War set a precedent for involvement in the Caribbean and the Pacific and set the American battle lines for war in the Pacific between 1941–5. American involvement in the Caribbean still continues today.

The capture of San Juan Heights made the position of the Spanish naval squadron untenable. Forced with the option of being sunk at anchor by American artillery, or breaking through the US naval blockade, Admiral Cervera reluctantly decided to sortie. The resulting naval action was short, brutal and one-sided. Within hours the American fleet had inflicted a crushing defeat on the Spaniards, who fought their unequal battle with notable courage.