CHAPTER 20

Implementing Risk Management within Middle Eastern Oil and Gas Companies

ALEXANDER LARSEN

Fellow, Institute of Risk Management (FIRM) and Honors Degree in Risk Management, Caledonian University, Glasgow, Scotland

This case study is based on real-life examples of Middle Eastern oil and gas companies where risk management has been put into place. The case study is a consolidation of the various approaches and captures the challenges of implementing risk management in the Middle East. For the purposes of this case study, the name MECO has been chosen to represent the numerous companies used to gather this data. Risk management has not yet been fully implemented in any of these companies, and they have had varying degrees of success. This case study is by no means intended to present a successful risk management implementation or best practices. Instead, it is meant to show the challenges in implementing and sustaining a successful program and the types of things that can lead to a breakdown of risk management.

COMPANY BACKGROUND

MECO is a national oil company established in 1940 when a Middle Eastern government granted a concession to a Western company in preference to a rival bid from a variety of Middle Eastern oil companies. It is among the world's most valuable companies, with an estimated value of $5 trillion to $10 trillion (U.S. dollars). MECO has some of the largest proven crude oil reserves, and is one of the largest daily oil producers across more than 100 oil and gas fields in the Middle East.

Currently, MECO has an exclusive right to explore in key countries across the Middle East, although there has recently been a huge interest in entry to the countries by large international oil companies (IOCs). This interest comes despite the political unrest across the region and the constant threat of wars. Additionally, while in the past there has been little threat of IOCs receiving rights to explore, recently there has been pressure on MECO to improve efficiency, as it lags significantly behind the IOCs.

Despite having exclusive rights, there is also the concern about diminishing reserves, and therefore a key focus for the organization is exploration and finding new oil fields. This, alongside its strategic decision to expand through new ventures, from partnering with international oil companies to acquiring foreign companies, means that the organization is in a major state of change.

Being a government-run organization, one of its key objectives is to provide energy to the populations of the countries in which it operates. This is provided at no profit. Recently, there has been a boom in population alongside an increase in car ownership and country expansion plans, which have pushed MECO's profits down. The more oil required to be delivered to the countries it operates in, the less oil there is to sell. This is another reason for the decision to expand and explore.

ORGANIZATION CULTURE

The culture of MECO is very much driven by its geography, history, and employees. Like many organizations in the region, being essentially a public-sector company, it is a large employer of Middle Eastern nationals while also relying heavily on a large expat population of which the majority are Westerners.1 This goes back to the organization's origins of being a Western company in the 1940s.

The company provides highly secure and lucrative employment in which benefits are vast, and most expats stay until retirement. It is not unusual to meet expats who have been with the company for decades. The same goes for the local Middle Eastern employees, who have often been educated by MECO and have continued their careers within the organization, never having experienced working anywhere other than at MECO.

In terms of career progression, it is very much judged on age and years at the company as opposed to merit, while the majority of very senior positions go to local Middle Eastern employees.

There is an aging workforce, with most employees having been with the company for over 20 years and being reluctant to change. Their view tends to be: “We have made a profit for 70 years, so why do we need risk management?” Due to a number of reasons during the late 1990s and early 2000s, including an oil price crash and regional instability due to the war in Iraq, MECO went through a period of being unable to recruit, and as a result, the organization now has an employee demographic of many young local workers and aging expat workers, with little in between. Due to the highly secure employment environment, there is often a lack of drive, innovation, and progress in terms of career development, and this can lead to serious change management issues.

LOCAL CULTURE

From a local culture perspective, not wanting to lose face is often an issue that comes up, and very often admitting to having risks in your workplace is considered a failure to do your job successfully. This being the case, it is not unusual to find that certain parts of the organization like to portray themselves as having no risks.

Another key factor tends to be the fact that nobody wants to be the bearer of bad news, which goes back to losing face. There have been instances where people turned up for a meeting but key individuals ended up not attending. No advanced warning was given by these key individuals, as it would have required them to “reject” the invitation, which is seen as negative.

Local culture is also very tribal, with a director having varying degrees of respect from employees or other directors based on their family ties. This can be a key area of opportunity for a risk management team trying to get buy-in for risk management if the team can capture the attention of the right directors. Tribalism also translates very often into the supply chain, where much of the supply chain is made up of regional players. While this can be advantageous in terms of having a good relationship with suppliers and allowing organizations to know who they are dealing with, it also opens up a huge risk of potential fraud.

There have been a few cases of fraud in Iraq and Kuwait that involved theft of oil through supply chains/relationships, or sabotage of foreign diesel shipments being delivered to project sites in order to ensure that organizations could get diesel only from local tribes.

It is important also to note that culturally, things move slowly and there is rarely a sense of urgency in getting work done; the locals prefer to put family, customs, and traditions first. What might seem like straightforward contract negotiations to more Western cultures will end up in long discussions and negotiations on various minor points of a deal over several long meetings. While this may seem counterproductive and unacceptable in Western organizations, it plays a key part in building up trust among business partners and allows for more flexibility and easier negotiations during later stages of a deal.

MECO STRUCTURE

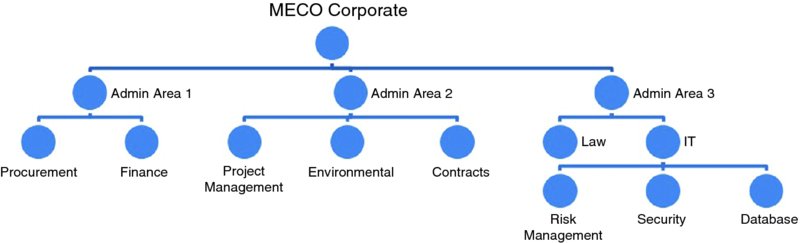

The structure of MECO includes five business lines with about five administrative areas in each. Each administrative area then has divisions, and within these are departments.

For example, there may be an Operational Services business line that has Industrial Services as an administrative area. Within Industrial Services there may be a Marine division and an Aviation division, which both have fleets of either ships or airplanes being managed by various departments within their respective divisions. This provides an indication of the potential size in these divisions. For example, the Marine division and Aviation division are the size of some small to medium-sized companies that are in existence today.

MECO RISK MANAGEMENT BACKGROUND

Early in 2006, after concluding a study on enterprise risk management (ERM), the Management Committee requested that the ERM team pursue formal project risk management (PRM) as a pilot under the ERM effort within the project management department. Scoping of the pilot began in late 2006 with pilot completion in March 2008. Since 2006, the ERM team has also been following up with other parts of the organization, such as information technology (IT) on its development and implementation of risk management within its organization.

Both project management and IT put together policy and procedure documentation, which was signed off by their division heads, as well as setting up project teams within their departments. These teams included a full-time member and a few part-time members. Within both departments, a Risk Committee was set up that consisted of members from the division as well as department heads whose responsibility would be to escalate those risks that were deemed to be outside their control and to ensure that existing risks were being managed.

In both instances, the project teams eventually transitioned into risk management functions within each department and have now started looking at other aspects of risk such as business continuity and quantitative risk analysis.

The successful implementation of risk management within the project management and IT departments, which was reported in 2009, went a long way to convince the Management Committee to implement a companywide approach to ERM. This companywide approach would mirror the approaches taken in the two departments. In 2009, the CEO, after announcing himself as chief risk officer, instructed Internal Audit to champion ERM with the specific remit of identifying the company's top risks from a bottom-up approach but without the use of consultants.2 Once work had been completed, it was expected that the risk management project team would come back to the Management Committee to report what the top 10 risks were.

In early 2010, Internal Audit put together an ERM project team made up of one full-time member and four part-time members (all with the title “auditor”). By the end of 2011, they had recruited a second full-time member, also under the title “auditor,” while the part-time members ceased to work with the team.3

The team was tasked with identifying the top risks facing the company from a bottom-up approach. The project leader did acknowledge that there should be some sort of framework in place and, despite not being part of the remit, he asked the team to consider a Risk Framework that could be suggested briefly to the Management Committee at the same time as the presentation of the top 10 risks. Assuming Management Committee agreement, this Risk Framework could then be implemented at a later date as part of a second phase.

It is important to note that in the Middle East it is commonplace to see risk management sitting within Internal Audit. This is mainly due to Internal Audit being among the first to be exposed to the concept of risk management as well as the fact that the major auditing firms see risk as a way to secure more business with their clients and will sell risk management as an auditing function. Approaches that would be frowned upon by these firms in Europe, Asia, or North America are widely accepted in the Middle East. This is also a major topic of argument between risk managers and auditing firms at ERM conferences across the region.

RISK MANAGEMENT PRACTICES WITHIN MECO

Information Technology

The risk management program has been in place for the past four years and has been driven by the vice president, who heads up Administrative Area 3 (see Exhibit 20.1) and sees the value in risk management. Each IT department identifies risk, and this forms part of the IT division's risk register. This is then reported up to the administrative area through the IT Risk Committee and eventually to the vice president. This is the most advanced administrative area in MECO with regard to risk management; it has been improving its risk management capabilities consistently over the years, and continues to make improvements to the program.

Exhibit 20.1 MECO Corporate Organization Chart

Other divisions within Administrative Area 3, such as Law, have not yet started a risk management program. However, due to the success of IT's risk management, the vice president has requested that other divisions take a lead from IT. IT will then work as consultants alongside the risk management project team and will be involved in setting it up throughout the administrative area.

IT has a Steering Committee, which oversees the risk to the division and escalates risks where appropriate (e.g., where they have no control of the risk or a decision needs to be made at a higher level). They ensure there is documentation in place as well as appropriate reporting lines.

The biggest risk that IT has is that of a severe cyber attack. Operations are linked to the main servers, which means that if the main IT system is down, that could affect operations, leading to a shutdown of facilities. This risk was identified and IT security was put in force in order to manage this risk. However, despite best efforts, there are about 150 hacking incidents a day, and not all of them are successfully stopped.

IT has 10 dedicated staff members, including their business continuity planning team, which is very strong for a division's risk function and shows the support that the program has within Administrative Area 3. The risk management project team is hopeful that once all divisions within the administrative area have risk management in place, other administrative areas will follow suit and replicate their success.

Project Management

Project management was one of the pilot exercises for ERM within MECO. Risk management was introduced as a requirement for projects within the team, and Activity Risk Holder (ARH) was purchased as a result. ARH is a risk management software tool that allows risks and actions to be captured across an organization and projects.

Risks have been identified and assessed across a large number of projects over the past couple of years, and extensive documentation has been developed to support the process. This has mainly been built, developed, and managed by one project risk manager. This manager has worked hard to build a substantial database of risks that the organization can use as lessons learned for future projects, as well as a decision making support function for project and investment decisions. Unfortunately, due to key elements not being in place, the risk management drive has been lost and the process has essentially been reduced to nothing.

The failures have come as a result of:

- Lack of active management support

- Lack of resourcing

- Lack of corporate Risk Framework that allows key project risks to be escalated

- Lack of key performance indicators (KPIs), risk appetite, or tolerances set at corporate levels

Finance

Finance risk management involves risk financing. Currently, the department identifies risks and assets of an insurable nature and makes sure that all insurances are in place. They have a captive insurance company and manage limits and exposures. There is a desire to be more aligned to an overarching ERM process in which to identify further insurable risks as well as provide support for risk financing needs of the company. The key challenge to making the risk management function more effectively is that there is no risk appetite or tolerance set at a corporate level.

Environmental Protection Department

Environmental protection plays a key part in managing risk within the organization. It is divided into three main functions:

- Environmental

- Occupational health

- Community health

Environmental protection deals with ensuring compliance to regulations, improving performance, and exceeding standards. Using a cradle-to-grave approach, it is involved at the start of projects or any potential use of new land. It has already been involved in moving the physical sites of major projects due to environmental issues. Environmental protection looks at site selection and considers wastewater, offshore versus onshore, emissions, and so on. It focuses on audit and monitoring.

If there is a need or a focus on, for example, old infrastructure, then it will identify project management as a key stakeholder and involve that department for certain improvements. This is reported into the environmental master plan, which covers these specific issues and has assigned budgets. Any gaps that need to be filled will be undertaken within this instrument.

Environmental protection monitors oil spills, and any oil spill is considered unacceptable. An oil spill is any spill of oil that is not part of normal operations (e.g., sweeping oil off a rig into the ocean is an oil spill).

The department has already identified aging pipelines as the major cause of spills, and all aging pipelines will be replaced. It has independent reporting lines and authority. During a crisis it acts as a resource in an advisory capacity.

Change in regulation is managed through formal channels. MECO acts as an adviser to the ministries nationally for potential regulation, balancing the public's needs with MECO's needs. Environmental protection provides input into all national environmental council suggestions.

Internationally, MECO has full-time employees working with ministries to support them when in meetings at the United Nations and so on. The Ministry of Petroleum usually attends.

Environmental protection uses a 3 × 3 matrix for effort and impact but does not capture risks in a traditional risk register.

Law

The law department currently has 25 or 26 members of staff within MECO. In most other major organizations, however, there can be hundreds of legal staff. There is an employee expansion initiative that will see an increase in legal staff of 50 percent over the next year.

Law gets involved with joint ventures, subsidiaries, government projects, and supporting due diligence. It plays a key part in contracts, as all contracts must be signed off by the law department.

The key functions are:

- Reviewing of contracts

- Setting up of contracts for joint ventures and so on

- In-country litigation and claims

- Out-of-country litigation and claims

- Antitrust (price fixing, etc.)

- Contract disputes

- Medical malpractice

- Tax and regulation

- Captives management

- Conflicts of interest/business ethics

- Patent filing and prosecution, mainly in the United States

- Boundary issues

- Mergers and acquisitions

- Aviation

- Corporate secretarial support for board, joint ventures, and so on

CORPORATE RISK EXERCISE

Risk Management Information Gathering Exercise (January 2010 to June 2011)

MECO undertook an extensive risk management information gathering exercise in order to provide the Management Committee with the key corporate risks. The risk management team had requested a workshop approach to the meeting in order to share the risks and get involvement from the Management Committee. However, this was rejected and a one-hour presentation was scheduled instead.

The ERM team met with the administrative areas' representatives. The team:

- Went over the history of ERM and outlined the purpose and key definitions

- Clarified the data collection form

- Consolidated this input to business line level, as appropriate, once input was received from all administrative areas and their divisions

The team had further discussion with compliance functions and key organizations. This step was necessary to help consolidate and prioritize business line risks to arrive at corporate-level risks. The team also integrated corporate planning input, which included particulars of internal and external risks as well as risks gathered from various publications. All this information made up the content of the Corporate Risk Register, which was used to derive MECO's risk profile.

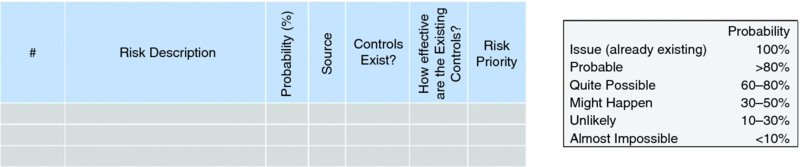

The template used can be seen in Exhibit 20.2.

Exhibit 20.2 MECO Corporate Risk Register Template

This is the template that was designed to collect the administrative area's and its divisions' risks. To ensure consistency of understanding, the team clarified each data entry column in a two-page document.

The key was to have the administrative area provide a risk number and a risk description; probability (in percentage terms); a source of the risk (internal, external, or shared); whether or not controls exist, and how effective these are (highly, partially, barely); and the risk priority (listing from 1 being the top risk, followed by 2, 3, and 4 for subsequent risks).

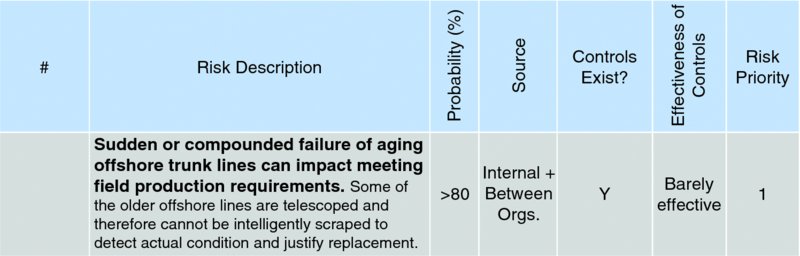

Exhibit 20.3 provides an example of the information received by the ERM team from the business.

Exhibit 20.3 Example of Risk Information Reviewed by the ERM Team

In this example, the risk, its cause, and its impact are all clear. Using the risk description and data in the remaining columns, the team analyzed the data in such a way that it helped them consolidate and prioritize the risks, to arrive at the relevant business line level and later at corporate level.

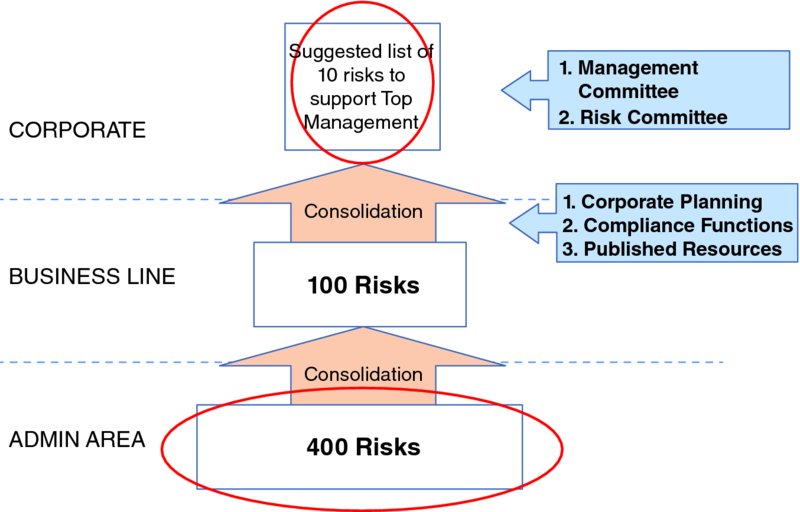

Consolidation

Receiving more than 400 risks from the administrative areas, consolidation was undertaken at a business line level to arrive at about 100 risks. This list was shared with compliance functions and corporate planning as well as considering various published resources and surveys to come to a final 10 risks. These risks were to be presented to the Management Committee in an hour-long presentation for consideration and confirmation as being the company's top risks. The approach can be seen in Exhibit 20.4.

Exhibit 20.4 Risk Analysis and Consolidation Approach

Risk Framework

While the top risks had been collected, consolidated, and reviewed by 2011, work also began in early 2011 to put together a proposed Risk Framework. This had not been part of the team's initial remit; however, it was felt that having a one-hour presentation with the Management Committee was too good an opportunity to pass up. By presenting this element to the Management Committee alongside the top risks as a way to ensure that an ongoing process of identifying risks was in place, this would add value to the presentation.

Risk Management Approach

The risk management approach that the risk management project team put together considered such things as which standards to adopt and how risk management would flow through the organization (ISO 31000 was the eventual decision due to the high regard for ISO in the Gulf region, which would support implementation of risk management in the long run).

The key documents that were drafted were risk policy, Risk Committee, risk maturity model, risk procedure, risk training material, and risk maturity matrix.

Risk Policy

The risk policy included key sections such as:

- Background and purpose

- Objectives

- Scope

- Definitions

- Policy statement

- Risk philosophy

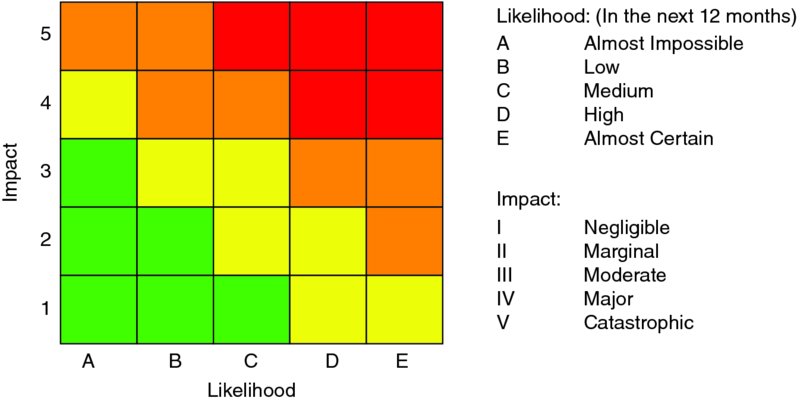

A traffic light system had essentially been suggested within the framework in the form of a 5 × 5 risk matrix that would help identify the organization's key risks. The matrix is shaded to indicate high, medium, and low importance. See Exhibit 20.5 for the risk matrix. Although this is a good system to use, the organization's risk tolerance and appetite had not been reviewed or set.

Exhibit 20.5 Risk Matrix

In order to set a risk tolerance, there needs to be a top-level decision as to what should be managed and what should not. Some interviews and a short workshop to assess and set the risk appetite and various tolerance levels were therefore discussed among the risk project team, which led into further discussions relating to having a Risk Committee.

Internal Audit had already noted to the Management Committee in previous meetings that it was difficult to meet with the Management Committee and that in order to implement risk management the team would need access to an overarching body that could make decisions on behalf of the Management Committee. The risk management team could then, along with a Risk Committee, set the tolerance level for the organization as well as approve and make changes to any risk documentation that was being developed.

While other more scientific methods of setting a risk tolerance and appetite were available, they would have required more time and the use of consultants, which had already been ruled out by the Management Committee.

Risk Committee

The risk management team was keen to establish a Risk Committee. The team understood the importance of the Risk Committee in supporting the implementation of the Risk Framework should the Management Committee agree to implement it.

The Risk Committee would be the link between the corporate risk register and the business lines and would act as a filter for the Management Committee. Risks from the business line risk registers could feed into the Risk Committee for consideration toward the corporate risk register. Equally, any major project risks or joint venture (JV)/partner risks could feed through the Risk Committee, too.

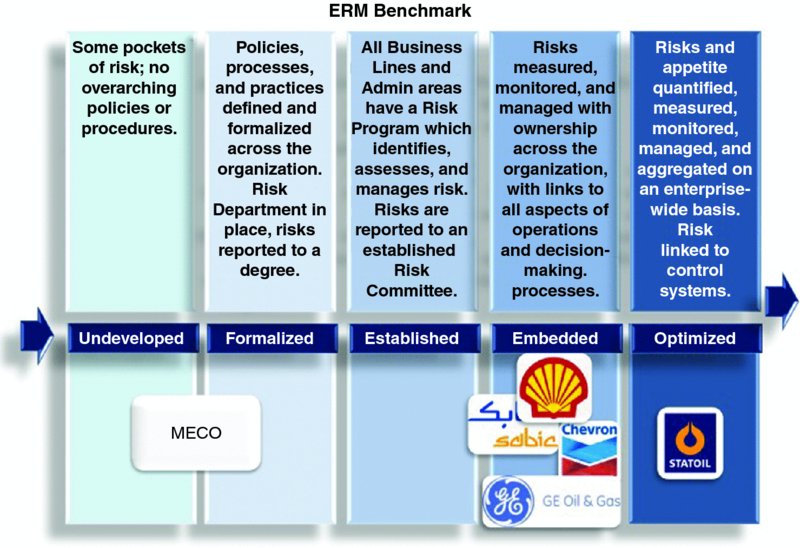

Risk Maturity

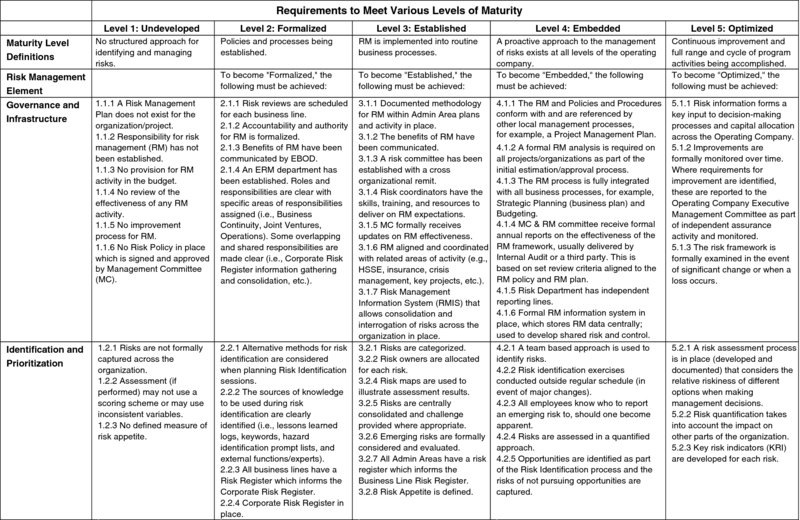

The team agreed that in order to progress with risk management, consideration needed to be given as to where they were now and where they wanted to be in terms of risk maturity. Additional work was therefore undertaken to create a risk maturity model specific to MECO, which can be seen in Exhibit 20.6.

Exhibit 20.6 MECO Risk Maturity Model

Risk Procedure

The risk procedure essentially expanded on the risk policy and gave a much more detailed account of the process of risk management, such as the traffic light system mentioned earlier in Exhibit 20.5, which was called a risk matrix.

The procedure also came with attachments such as: reporting structure, Risk Committee charter, assessment criteria (which expanded upon the 5 × 5 matrix and quantified it to an extent), example risk register, and example action plan.

Risk Training Material

The risk management team had been providing various training to the organization for some time, and it was agreed that something more formal should be put in place. First, training presentations were gathered from around MECO and consolidated into one agreed training presentation. Second, the team started the process of making it align with the Institute of Risk Management (IRM), which has a strong presence in the region as well as in Europe. The idea was to create training that would provide delegates with a certificate of attendance from the IRM to make it more attractive and beneficial. There were also tiers of training to be provided depending on the audience (managers, general staff, project managers, and risk coordinators).

Risk Maturity Matrix

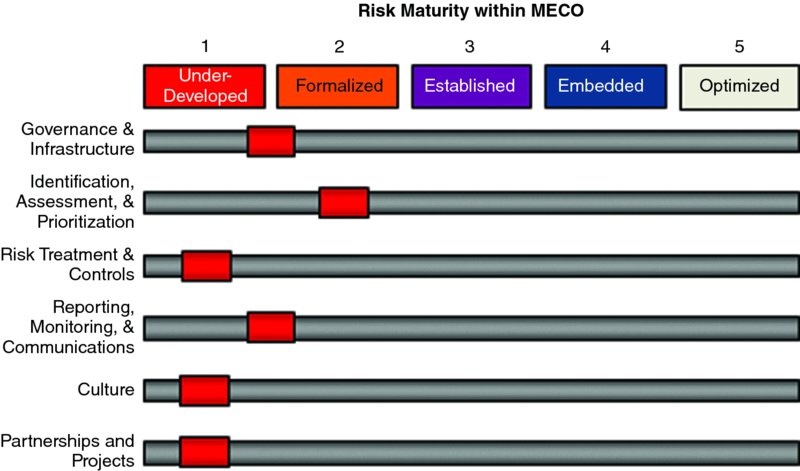

The risk maturity matrix was to be the key to the future success of risk management implementation. It would provide requirements and a road map to implementing risk management successfully throughout the organization based on the ISO 31000 model. It provided for a five-phase approach with clear and practical requirements to progression that any part of the organization could follow.

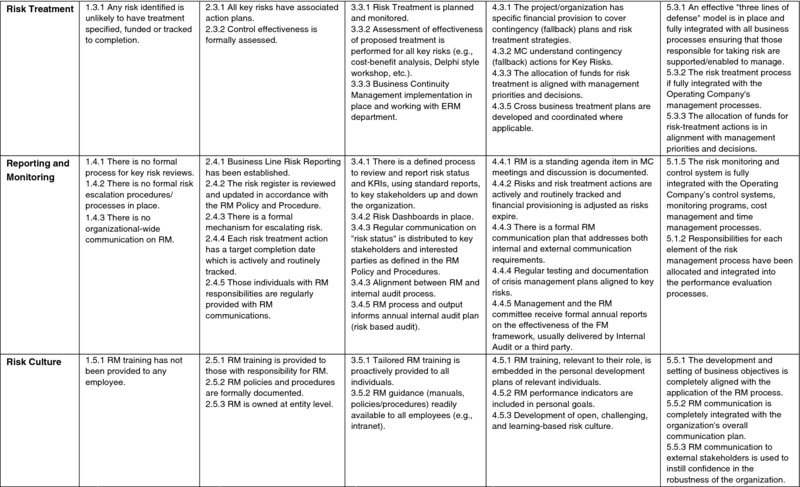

Based on the points within the matrix, a self-assessment was carried out in order to map out MECO's current maturity levels. These were presented in a simplified risk matrix in order to present the findings to the Management Committee, which can be found in Exhibit 20.7. The same methodology was used to measure and benchmark what maturity levels other oil and gas organizations had reached. This was mapped in a graphic that would be used to encourage top management to support ERM in order to reach similar maturity levels as competitors. The benchmark can be found in Exhibit 20.8.

Exhibit 20.7 Simplified Risk Matrix

Exhibit 20.8 Maturity Level Benchmark

Exhibits 20.9, 20.10., 20.11, and 20.12 provide lists of potential corporate risks that have been identified by other companies (Shell and BP) and organizations (E&Y and AON), which apply to the energy and chemical industries.

|

Source: AON Global Chemical Business Survey 2011.

Exhibit 20.9 Benchmarks from AON Survey

|

Source: E&Y Global Oil & Gas Survey 2011.

Exhibit 20.10 Benchmarks from E&Y Survey

|

Source: BP Corporate Risk Register.

Exhibit 20.11 Benchmarks from BP

|

Source: Shell Corporate Risk Register.

Exhibit 20.12 Benchmarks from Shell

Management Committee Meeting, December 2011

The risk management team finally presented the top risks to the Management Committee, as well as their suggested way forward, in a one-hour meeting in December 2011. This was almost two years after the request by the Management Committee. As mentioned earlier, the risk management team had requested a workshop approach to the meeting in order to share the risks and get involvement from the Management Committee. However, this was rejected and a one-hour presentation was scheduled instead.

The reactions were mixed, with many of the Management Committee members dismissing the risks as business issues and others questioning where they had come from (despite having signed off on them following the administrative areas' initial risks being sent to the risk management team).

The CEO remained positive and understood the need for a more corporate discussion around the identified risks. The group listened to the suggested approach and of having a Risk Committee. However, a majority opposed the idea of another committee being set up, and it was suggested that the risk management team use the Advisory Committee as a Risk Committee in order to progress their Risk Framework documentation and to review and filter the top risks before another meeting with the Management Committee.

The Advisory Committee is essentially a subcommittee of the Management Committee that vets upcoming agenda items and is made up of some Management Committee members.

Following the conclusion of the meeting, the risk management team was unable to get a time slot to see the Advisory Committee for over four months. Therefore, all documentation remained as drafts, and the risk information started to age with no formal process in place to identify and update risks.

Operational Excellence, June 2012 to December 2012

During the second part of 2012, a major initiative was put in place to implement Operational Excellence within the organization. The risk management team, still waiting for a meeting with the Advisory Committee, identified this as an opportunity to embed risk management without the need for authority or needing to convince each administrative area of the benefits.

Through relationship building and awareness of risk management, the risk management team managed to incorporate risk management into the Operational Excellence plan as being a key enabler. In other words, upon completion of the initiative in late 2013, and in order to meet its aspiration of Operational Excellence, MECO (all business lines and their administrative areas) would be asked to implement all key enablers of Operational Excellence, one of which, as stated, would be risk management. This would be a major initiative and would require a large number of consultants coming in to work on Operational Excellence implementation.

Previously, the risk management team had been seen as a team with a self-serving purpose who were trying to force new processes on the organization. Operational Excellence was therefore a huge opportunity for the risk management team, who hoped they would now be looked upon as a useful resource that would support the organization when it came to having to implement Operational Excellence requirements.

Risk Management Move to Corporate Planning, December 2012 to Present

By December 2012, over a year after the Management Committee meeting where the risk management team was instructed to use the Advisory Committee in order to progress risk management, a meeting had still not been set up. The CEO realized that risk management needed more authority and as a result instructed the Corporate Planning division, which was a major influencer in the organization and had a well-regarded vice president, to set up risk management as a function within that division.

Risk management would now form a part of the corporate planning structure with a manager and the two team members from the project team. The management would look to recruit up to three new members to the team, and the team's remit would be to set up an ERM framework, identify the top risks to the company, work on identifying risks to future investments, and form an integral part of the future corporate planning process.

Corporate Planning has a direct line to the CEO and has a large influence within the organization. This helped to ensure that within weeks of creating the function, meetings were set up for February 2013 with the Advisory Committee in order to review and confirm the top risks. Plans were already in place to fast-track the production of the Risk Framework documentation from their draft forms, with the risk management team having the authority to decide much of the approach.

One of the key areas of consideration going forward was implementation of a risk management information system (RMIS), and therefore the risk team started undertaking a RMIS study in order to identify appropriate software for the organization.

Moving the risk management team to an actual department meant that the team members would finally feel part of a real team. They would also have a proper remit and authority to undertake and implement risk management properly, while having much better access to decision-making authorities such as the Advisory Committee. Additionally, the fact that the CEO had made this decision meant that the Advisory Committee would probably fall in line more and support risk management.

Despite these positives, the risk management team would face challenges in terms of meeting the requirements of their remit based on their staffing numbers. Despite aspirations to recruit more members to the team, risk professionals are not easy to come by, and the fact that it takes six months to actually complete the recruiting process means that six months can easily become a year.

By early 2014, MECO was finally able to start filling roles, and it now has a team of 15 risk members at varying levels from analyst and business continuity roles up to manager positions. Another key decision was to allow consultants to support ERM implementation, and invitations to tender have now been sent out for millions of dollars' worth of consultancy business.

CONCLUSION

Risk management in MECO was a lengthy, drawn-out process for a number of reasons. The key reasons for the long process were a lack of a clearly defined scope, lack of authority, staffing limitations, slow corporate culture, and resistance to change. Risk management, had it been approached correctly, could have been successful much earlier. This is reflected in the IT and Project Management examples whereby success was dependent on staffing and buy-in from the top. Management needs to understand the benefits and be seen to support the process.

Within an organization such as MECO, support from the top is vital. Having a framework in place that was bought into by the CEO would have likely increased the chances of success. Additionally, the poor placement of the risk management team was another hindrance. This is all too often the case with risk management not being established as a department from the outset. Few risk professionals will be happy joining a newly formed risk management team or department that doesn't sit within a relevant and powerful division or have independent reporting lines.

Within MECO, the organization was asked to identify risk without having undertaken training, without a consistent framework or procedure to follow. Also the survey was not scientific in its approach.

Despite the positive move to the Corporate Planning division, the risk management team lost a staff member, who it took a year to replace. This has meant that many of the objectives set out for the team were not met and the organization had started losing faith in the department, setting it back yet again. This makes it a challenge for the newly established team of 15 to regain buy-in from lower levels of the organization despite finally getting support from top levels.

NOTES

QUESTIONS

-

Prior to the Risk Management Information Gathering Exercise discussed earlier in the case, consider the challenges of the newly formed project team in undertaking Risk Management in such a situation.

-

- Discuss the challenges and how each of the departments might interact with and support Risk Management across the organization.

- What are the major differences between IT and Project Management, considering they were both part of the initial Risk Management pilot? How might they have overcome this?

-

- What do you think were the major positives of the approach undertaken with regard to the risk management information gathering exercise?

- What do you think were the challenges and pitfalls of gathering data in the way that they did?

-

What are the key challenges to the risk framework and risk approach proposed in 2011 by the risk management team?

-

Despite Operational Excellence providing the perfect platform to push Risk Management, discuss what the potential pitfalls may be.

-

Using the supporting documentation along with the case study information (Exhibits 20.9, 20.10, 20.11, and 20.12), provide a list of potential corporate risks that might have been identified by the project team.

NOTES

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Alexander Larsen, Fellow, Institute of Risk Management (FIRM), holds a degree in risk management from Glasgow Caledonian University and has more than 10 years of experience within risk management across a wide range of sectors, including oil and gas, construction, utilities, finance, and the public sector. He has considerable expertise in training and working with organizations to develop, enhance, and embed their enterprise risk management (ERM), business continuity management (BCM), and partnership management processes.

Alexander spent the first half of his career in the United Kingdom working in senior risk consultancy roles with Marsh and Zurich before leaving to join Det Norske Veritas (DNV) in Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates with responsibility of developing their risk management services for the energy sector in the Middle East and Asia.

Since leaving DNV he has worked in the Middle East in a variety of roles. Prior to joining Lukoil, where he is currently Risk Manager for the West Qurna 2 Asset in Iraq, Alexander worked with a number of oil and gas companies, developing and implementing ERM frameworks and business continuity management within the Qatar Foundation.