Higher Returns on Investment

Twice the Satisfaction for Half the Resources

Efficiency is intelligent laziness.

—David Dunham

Nature uses as little as possible of anything.

—Johannes Keppler

When you have Enough, you have everything you need. There’s nothing extra to weigh you down, distract, or distress you. Enough is a fearless place. A trusting place. An honest and self-observant place … To let go of clutter, then, is not deprivation; it’s lightening up and opening up space and time for something new and wonderful to happen.

—Vicki Robin

Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.

—Leonardo da Vinci

For all objects and experiences, there is a quantity that has optimum value. Above that quantity, the variable becomes toxic. To fall below that value is to be deprived.

—Gregory Bateson

One of the most versatile tools we have for creating greater value from fewer resources is efficiency. In this time of great transition, we ask each other, a little desperately, “What should we do now?” The answer is simple: change our lifestyle to fit reality, rather than continuing to stretch reality to fit our addictive lifestyle. Although supplies of fossil fuels, minerals, and clean water are becoming

less abundant and accessible, limitless reserves of human creativity remain untapped. We can use this nonpolluting source of energy to transition to a new way of valuing the world. That’s what we’re equipped to do: adapt, improvise, and create. However, if we refuse to make exciting, adventurous changes now, our options will quickly narrow. For one thing, nature is starting to look like the empty tables of a discount store during a going-out-of-business sale.

In our current economic paradigm, profits and prices are often the only variables considered in a given decision or transaction; “If it makes monetary sense, let’s go with it.” But in the next era—now coming clearly into focus—ecological efficiency will be the dominant accounting tool, because resource realities have radically changed in our generation. We’ve never lived in a world so stripped of natural abundance, and the world’s population is growing at the rate of another Turkey-size country every year. Standard operating procedures are no longer appropriate. So accountants and investors will not just ask, “How much oil can be pumped, how fast?” but “How much expensive energy does it take to pump, ship, and refine the oil?” Not just, “How cheaply can we manufacture and market our widget?” but “How brilliantly can we design the product so it uses the least amount of resources possible, fits nature like a glove, and precisely meets the needs of people?” In other words, how much value do our efforts and designs actually deliver? Consumers of the near future will demand nothing less.

We’ll base our economy on things like nutrition per molecule of food, and the quality of work accomplished per unit of energy. We’ll buy houses based on how well they satisfy our needs per square foot; and evaluate the efficiency of a car not just by miles per gallon, but by the number of peoplemiles per gallon. These new ways of living won’t be thought of as sacrifices, they’ll just become part of a new everyday ethic—the way we do it now. In all likelihood, future generations will look back at our high-consumption era—before the change—and ask, “What the hell were they thinking? How could they be so sloppy?” (They may even include us in a lumped-together era known as the Dark Ages.)

I believe meeting needs precisely should be the fundamental organizing principle in creating a new civilization, one mind, one commitment, and one policy at a time. A needs-meeting approach answers the question, “Exactly what results do we get from our efforts, designs, and inputs?” I propose that we pay greater attention to what minds, bodies, nature, and culture

really need, and supply those needs to create a trim, zero-waste, zero-regret lifestyle.

Simple. You and I don’t have to be rocket or even rock scientists; we just have to get deeper satisfaction from more meaningful, better-designed products as well as nonmaterial forms of real wealth. In the following chapters, I suggest various ways to get more value out of the energy we use, the houses we live in, and the food we eat. I’m not talking about “back to the basics,” but rather “forward to greater inspiration and satisfaction,” by mindfully meeting needs more fully. What’s log-jamming our era is that we try to meet so many human needs with purchased commodities that are poorly designed, out of scale, and filled with dubious ingredients.

Imagine a healthy, satisfied Pacific Islander relaxing in a hammock that swings gently in front of a seaside hut made from palm fronds. He plays a wooden flute for his family and himself, and for dinner, he picks delicious tropical fruits and enjoys fresh sunfish roasted on an open fire. His family feels happy—lucky to be alive. They are meeting physical, emotional and psychological needs directly. Suddenly, like a tsunami, affluenza sweeps across the island. “A businessman arrives,” writes Jerry Mander, “buys all the land, cuts down the trees and builds a factory. He hires the native to work in it for money so that someday the native can afford canned fruit and fish from the mainland, a nice cinderblock house near the beach with a view of the water, and weekends off to enjoy it.”1

Suddenly, like most of us, the family tries to meet needs with products of lesser quality and that cost huge amounts of life energy to buy. I’m not suggesting that we should all live in thatched-roof huts, but simply that we should rely on efficiency (no waste), sufficiency (the right amount), and design (the right stuff) to meet needs directly. (In addition, we should vote that invasive, profiteering company off the island!)

I used to think that wants were somehow superior to needs—that as we progress from basics like food, housing, affection, identity, and community to “loftier” goals like speedboats, second homes, or Dom Perignon champagne, we automatically become happier. In recent years it’s become clearer to me that if happiness, balance, and meaning are primary goals, we stand a better chance of achieving them by squarely meeting needs than by obediently chasing wants. Like the Pacific Islander who now punches a time clock, we aren’t meeting our needs well. For example, the diet of many Americans isn’t based on what human bodies need to be

healthy. The human body requires certain minerals, enzymes, and amino acids, and is equipped to digest certain foods; but many are in the habit of ignoring these anthropological parameters. Instead many eat from brightly colored packages that contain energy in the wrong places; the processing, packaging, and delivery of the food is rich in energy but often the food itself is not!

When we meet needs poorly, the result is discomfort and vulnerability. Really, how can we expect junk food that delivers obesity, anxiety, gum disease, osteoporosis, diabetes, depression, heart disease, cancer—and more—to make us happy? Unfortunately, we get dissatisfaction and dysfunction instead, which often compel us to acquire even more consumer goods to “fill ourselves up.” Lacking energy, buoyancy, and self-confidence, we become vulnerable to the booming voices of the Market. We continue to consume more than we need partly because we’re not at ease. Besides nutrition, we fail to satisfy other physical needs, such as water, sleep, sex, and housing. And we fail to meet psychological and spiritual needs, too, such as affection, connection, autonomy, and spirituality.

On the physical side, if a person lives in a house with five or six extra rooms that are never used yet have to be maintained, heated, cooled, and amortized, do the benefits of that large house outweigh the liabilities? By living in more space than he or she needs, isn’t this person creating discomfort elsewhere, for example in biological habitats that are severely damaged to harvest building materials? Or in the creation of catastrophic weather patterns caused by global warming, which is in turn partly caused by the energy that house uses? Even if this person doesn’t realize it, side effects cascade exponentially back into his or her own life, and into the lives of many others.

Is our learned desire for a trophy house really more valuable than the deep-seated human need for a home (and environment) that teems with life? Do we feel so secure in our inside world that we’re willing to give up the outside, natural world for it? Is the air-conditioned, sometimes toxic indoor-universe really meeting our needs?

Donella Meadows cuts to the core of needs meeting in the book Beyond the Limits:

• People don’t need enormous cars; they need respect. They don’t need closetsful of clothes; they need to feel attractive and they need excitement and variety and beauty.

• People don’t need electronic entertainment; they need something worthwhile to do with their lives … People need identity, community, challenge, acknowledgment, love, joy.

• To try to fill these needs with material things is to set up an unquenchable appetite for false solutions to real and never-satisfied problems. The resulting psychological emptiness is one of the major forces behind the desire for material growth.2

To build on Meadows’s statement, it’s not money or things per se that we need, but value. Not coal or oil per se, but energy to refrigerate our food and clean our clothes. Renewable sources of energy in conjunction with appliances that use less energy can deliver these services even better, overall; they deliver services with fewer side effects. It’s not meat per se we need but protein, which is also contained in other, less resource-intensive foods. It’s not prescription pills we need, but a healthy lifestyle that prevents illness. We don’t need an endless stream of negativity on the evening news but rather stories that show us by example how to live ethically. It’s not just facts we need to teach and learn in our schools, but an understanding of relationships and how whole systems fit together. Our waste-filled, often misguided lifestyle keeps generating deficient products and services that miss their targets—sometimes as widely as if acupuncture were applied randomly, or baseballs were thrown by a broken pitching machine.

Let’s face it, with larger populations consuming more stuff faster and faster, we often feel overwhelmed by a world littered with Jetson-esque viaducts, broken gadgets, and packing peanuts. A good half of the resources, time, and human energy spent in our economy results in frustration, illness shame, or guilt rather than real value. In a way, waste and dissatisfaction have become America’s most lucrative products. When resources seem infinite, who needs precision? When schedules are tight, who has time to care? But believe it or not, these bad habits are actually welcome news in our time of great change, because they provide a bridge to a better quality of life. By reducing the waste and carelessness that now litter our economy—with better design, greater efficiency, and less consumption—we can finance the coming transition to a less destructive, more satisfying future.

Our economic strategy will change—from using resources quickly to using resources well. By getting greater value from each molecule, each electron, each drop of water, as well as each moment, we can create richer lives without sacrifice. The new American lifestyle is not about what we give up (remember, we only need to get rid of the dysfunction and excess) but what we get.

A central theme of this book is that when we become obsessed with wants, the root cause may be that we’re off balance because of the dysfunctional ways we try to meet our needs. Our relationships aren’t satisfying, our drinking water is contaminated, we aren’t stimulated by our work, and so on. We’re taught in school and in the media that basic needs are already achieved for most Americans; and that, in any case, meeting needs is not as worthwhile and “fun” as is satisfying wants. But I strongly disagree. Many billionaire CEOs hope we remain meekly dependent on deficient products, services, and experiences because, when we take charge of meeting some of our own needs (such as entertaining ourselves, maintaining our health, or changing our own oil), we don’t consume as much. In a wasteful, design-challenged economy that often leaves us feeling empty, my priority is to slow down, fully satisfy needs, and let the wants go find some other sucker. “For fast-acting relief,” suggests Lily Tomlin, “try slowing down.”

The Excessive Material “Needs” of an Average American Lifetime

During its life, the average American baby will consume 3.6 million pounds of minerals, metals, and fuels! Now multiply that times 300 million … By using more efficient technology, reducing waste, and knowing when enough is enough in our personal lives, we can easily cut that mountain of materials in half.

| 572,052 pounds of coal | 1.64 million pounds of stone, sand, and gravel | 82,634 gallons of petroleum |

| 69,789 pounds of cement | 34,045 pounds of iron ore | 25,244 pounds of phosphate rock |

| 6,176 pounds of bauxite | 1.692 Troy ounces of gold | 22,388 pounds of clay |

| 1,544 pounds of copper | 31,266 pounds of salt | 28,564 pounds of misc. minerals, metals |

| 849 pounds of zinc | 5.59 million cubic feet of natural gas | 849 pounds of lead |

Source: Mineral Information Institute, Golden, Colorado (www.mii.org), 2005

Mario Kamenetzky, formerly with the World Bank, wrote, “Human needs are ontological facts of life. Failure to satisfy them results in progressive human malfunctions, whereas unsatisfied wants lead to little worse than frustration.”3 Yet, in our world, the two categories often get mushed together like wads of Silly Putty. Wants become perceived “needs.” For example, in a recent USA Today poll, 46 percent could not even imagine life without a personal computer (38 percent specified with “high-speed Internet”), and 41 percent felt the same way about their cell phone. But I’m guessing many could quite easily imagine life without leafy greens or organic grains rich in essential minerals.

A moment of truth—an “aha” moment—comes when we realize we’ve been duped by a value system based primarily on material objects and values. We realize that the way we live now is just something the marketers and inventors made up! In many cases, it’s not based on biological or even psychological needs, but simply on the fact that someone has invented something (often accidentally) and wants to make a buck. In our way of life, we’re instructed to select happiness from an endless display of goods and services—many of them defective or wasteful—but there’s very little education about how to have “enough,” the perfect amount. After being told three million times that Frosted Flakes contains more happiness than oatmeal does, we begin to believe it. But our bodies, psyches, and even bank accounts tell us differently.

Many are familiar with Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. A pioneer of the Human Potential Movement, Maslow theorized that by meeting material needs (e.g., sleep, food, and water) and social needs (e.g., safety, security, and self-esteem), we ascend through moral needs (e.g., truth, justice and meaning) to the apex of the pyramid: self-actualization (presumably, only a few rungs from Heaven). This model is actually very useful, because it illustrates that humans can become truly satisfied by meeting anthropological needs.

However, Maslow’s model has several shortcomings, in my opinion. First, being a hierarchy, it implies that we must rise above the muck of survival needs to become happy; that a low-income person struggling to put food on the table can’t have a strong sense of justice, beauty, or self-esteem. Secondly, it doesn’t evaluate how well a need is met. How clean are the air and water that meet our survival needs at the base of the pyramid? How resilient is the community in which we exchange affection, love, and acceptance? Precisely how are security needs met—with a $400 billion military budget, or a sense of trust in your neighbors?

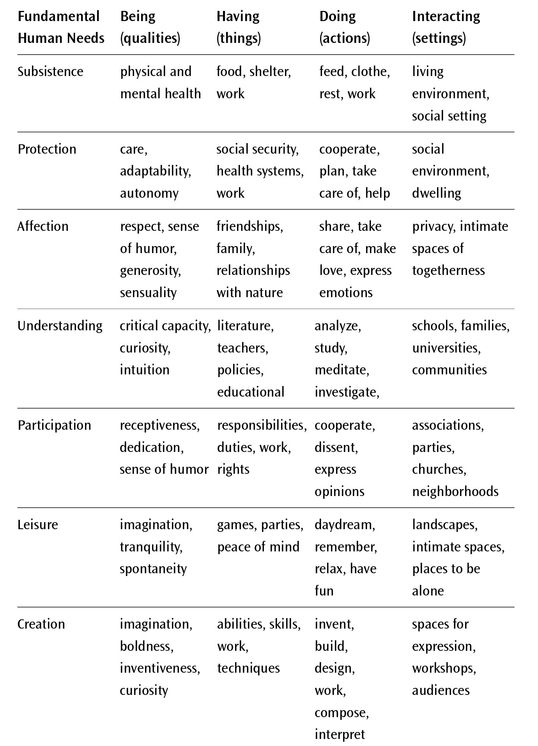

As I began to research this book, a colleague asked if I’d seen the needs analysis work of Chilean economist Manfred Max-Neef. In the book Real-life Economics, edited by Max-Neef and Paul Ekins, I found a great “lens” for looking at value. Max-Neef’s work is right in line with the scope of this book. Max-Neef proposes that in contrast to wants, which are infinite and essentially insatiable, basic needs are “finite, few, and classifiable.” (What a relief—they are actually achievable!) “Needs are the same in all cultures and all historical periods,” he writes. “Whether a person belongs to a consumerist or to an ascetic society, his/her fundamental human needs are the same … What changes, both over time and through cultures, is the way the needs are satisfied.”4

Bingo. That’s a major reason why we consume more than “enough”: because of the excessive and shoddy ways we try to satisfy our needs. Our culture has been clobbered by advertising, peer pressure, defective economic policies, and the encoded emotions of fear, insecurity, and doubt. In addition, we’re programmed to believe that natural ways of meeting needs are inferior, though a sizable chunk of our economy is beginning to question that programming. “Alternative” health and wellness practices—many of which have been around for thousands of years—are coming back into the mainstream. For example, many insurance companies now pay for chiropractics and acupuncture. Organic food—which we’ve eaten for 99.9999 … percent of our time as a species—is becoming normal or at least acceptable once again. People are beginning to actually understand what their bodies need, to feel healthy and content.

Commenting on the Max-Neef model, Terry Gips, president of the Alliance for Sustainability, says, “The good news ecologically is that it is possible to actually have more satisfaction with less stuff, because it’s not the materials and energy that provide satisfaction, but the degree to which basic needs are met.” Gips is a longtime advocate of sustainability who uses the Max-Neef matrix of needs in workshops and presentations to demonstrate how we often miss the mark, remaining dissatisfied. “It’s a great tool for helping people find shared values,” says Gips. “I used Max-Neef’s ideas in a design workshop for a $2.7 million renovation of a Minneapolis church. Our discussion about the interrelationship of needs resulted in a space that people love to use for meetings, that’s easier for custodians to clean, that has better lighting, and that has operable windows for greater comfort and participation.”5

By choosing more appropriate satisfiers for each of Max-Neef’s nine fundamental needs—subsistence, protection/security, affection, understanding, participation, leisure, creation, identity/meaning, and freedom—we can be happier with less consumption. One of the reasons why is that choosing the most complete satisfier fulfills more than one need at a time. We also pay attention to the needs of other people and the environment, becoming something grander than an ego in the process.

Fundamental Human Needs Matrix, by Manfred Max-Neef

For example, feeding a baby with formula meets nutritional needs fairly well (depending on the brand); but breast feeding, in addition to giving the baby better nutrition, also supplies a mutual need for bonding, affection, and building the infant’s self-esteem. Similarly, a prescription drug may treat the symptoms of an ailment, but preventive health approaches are more likely to treat the cause of the illness (such as stress, or unhealthy diet). They meet the human needs for participation (e.g., in one’s own health) and for understanding (e.g., how nature works). They also avoid bizarre side effects like my mother experienced: She took a drug to reduce cholesterol that also reduced her ability to use her hands effectively.

When needs remain unmet but we reach for wants anyway, we leave gaping holes in our lives. “Any fundamental need that is not adequately satisfied reveals a human poverty,” writes Max-Neef. Some examples are: poverty of subsistence (due to insufficient income, food, shelter, etc.), of understanding (due to poor quality of education), and of participation (due to discrimination against women, children, and minorities). We face similar poverties throughout our economy. There are far too many side effects in the way we eat, sleep, form community, create housing, and get around. Basic needs remain unmet because of bad choices, design flaws, and inefficiencies. As a result, we feel physically and psychologically deficient, which we try to overcome by consuming more defective goods and

services. When we relearn how to meet fundamental needs well, many of the wants will just wither away, because we’ll feel more self-reliant, and more content.

Max-Neef considers the way a culture meets needs a defining aspect of that culture. This is a key concept for the themes in this book, because many of the ways we meet needs are flawed, superficial, and based strictly on that abstraction known as currency; on quantity rather than quality. Because individuals learn behavior culturally, our challenge is to reshape our culture to fit reality.

We are so accustomed to buying our lives that we forget we can meet many needs naturally. For example, frequent sex (once or twice a week) has been proven to deliver various physical benefits such as 30 percent higher levels of immunoglobulin A, which boosts the immune system. A large percentage of the advertising that bombards us capitalizes on the benefits and compulsions of sex. Although it’s true that even a prostitute could supply some of the physical benefits, to satisfy basic needs for affection, trust, and emotional connection, only real intimacy will work. It is for this reason that men who have a significant bond with another person are half as likely to have a fatal heart attack. And studies have shown that the hugs that accompany a close relationship dramatically lower blood pressure and boost blood levels of stress-reducing oxytocin, especially in women. When researchers asked couples to sit close to one another and talk for ten minutes, then share a long hug, they measured slight positive changes in both blood pressure and oxytocin.6;7

What about sleep, another of Max-Neef’s subsistence needs? It’s clear that various substances in our familiar, hyperactive lifestyle often sabotage sleep, which we compensate for with sleeping pills. Our bodies become battlegrounds of conflicting biochemical responses. Contentedness is not really a possibility when we’re exhausted from sleeplessness, but vulnerability and loss of self-esteem are.

Habits clash with biology when we eat large meals before going to bed. We need about three hours to digest dinner but sometimes, especially in European cultures that dine late, we are still digesting as we try to sleep. The average American consumes about two to three cups of coffee a day. But many also consume two or more caffeinated sodas and a little chocolate, too, resulting in sheep counting, mantra reciting, and compulsive

snacking in the wee hours. And caffeine isn’t the only stimulant that screws up our sleep; although alcohol relaxes us when we drink it, it later becomes a stimulant. Once again, moderation is the way to go. Beyond “enough” is the “too much” that keeps us awake. (The word “moderation” doesn’t apply to tobacco, another substance that disrupts sleep, because its main appeal is that it’s a legal addiction. As someone who was once briefly addicted, I say, Just don’t go there!) We sometimes think a given problem is all in our head, but often it’s in our endocrine system or stomach. If we are dehydrated, our body feels a sense of alarm—“something is wrong”—which can also disrupt sleep. (But the right time to drink water is in the morning and afternoon, not evening).

According to psychologist Richard Friedman, it’s quite normal to wake up in the middle of the night, as many humans and animals do routinely. It’s even physiologically normal to be awake for an hour or two. The problem comes when the “gears” begin to turn and we become increasingly conscious; thoughts begin to focus on what needs to be done tomorrow and what we did wrong yesterday. I keep a good magazine by the bed for when that happens, and I’m learning that after a half hour of article reading, I fall back to sleep without any negative consequences. If I get less sleep than usual, I make sure to exercise the next day and stay away from processed food. I don’t feel sleep deprived, and I sleep fine the next night. It really helps to know that nature will provide the sleep we need.

In the United States, we eat slightly more than a ton of food a year (and it sometimes seems like a large portion of that is consumed on Thanksgiving Day). But how much of that food supplies nutrients our bodies and psyches can actually use? Does the American diet really meet our needs? The federal government’s Food Guide Pyramid recommends a diet high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, low-fat milk, lean meats, poultry, fish, beans, eggs, and nuts; and low in saturated fats, trans fats, cholesterol, salt, and added sugars. But to the average American, it’s too boring to eat vegetables (because they typically aren’t fresh) or to learn what exactly a trans fat is. So this average American simplifies—and companies like Kraft, ConAgra, and PepsiCo are delighted to help.

Says anthropologist Katharine Milton, “A wild monkey eats better than Americans do!” The monkey has a diet richer in essential vitamins and minerals, fatty acids, and dietary fiber than the more intelligent (ahem) Homo sapiens americanus. Milton followed monkeys through tropical rain forests with plastic bags, picking up the food they dropped from the trees. “They would bite off the tips of leaves and throw the rest away,” says Milton, who analyzed the leaves and found that the tips were especially nutritious. If

Americans followed a similar strategy, would we eat the cardboard box a fast-food burger comes in, for the fiber, and throw away the fatty burger and white bread bun? Research now pouring in about excessive fat, sugar, and refined carbohydrates tends to suggest that. Even meat, an American institution, is coming under fire. In today’s news, federal health officials have approved the spraying of bacteria-eating viruses onto meat and poultry products just before they are packaged. This approval is well intentioned, since meat infected with the listeria bacteria does infect an estimated 2,500 Americans every year, killing 500.8

Yet, a more systemic problem is the way meat is produced, with a potential for contamination on a much larger scale. Forced to eat grain and beans they aren’t equipped to digest well, and housed in close quarters where disease spreads quickly, livestock are routinely injected with heavy doses of antibiotics. Mutant strains of bacteria may evolve resistance to the antibiotics, in effect making feedlots potential “bacteria factories.” A case in point is the recent, widespread contamination of spinach with a strain of E. coli that grows in the stomachs of grain fed cows but not grass-fed cows. Apparently, some of the manure got into the irrigation water of farms in the region.

In terms of overall calories, the government’s Center for Nutritional Policy recommends from 1,600 calories for sedentary women and older adults to 2,800 calories for teenage boys and active adults; but Americans wolf an average of 3,800 calories. This tally includes two-fifths more refined grains and a fourth more of both added fats and sugars than in 1985. We’re literally consuming more than enough, eating as much for “fun” as we are for health. As with other matters concerning health and the environment, scientists can’t seem to figure out what humans should be eating. We don’t differentiate between good fats and bad, good carbs and bad, good sugars and bad. We act as if we’re carnivores, hunting ground chuck and veal cutlets like the great cats of the Serengeti hunt gazelles and wildebeests. But anatomy may tell a different story.

“I think the evidence is pretty clear,” says cardiologist William C. Roberts, from the beefy state of Texas. “Humans are not physiologically designed to eat meat. If you look at the various characteristics of carnivores versus herbivores, it doesn’t take a genius to see where humans line up.” (He points out that while a carnivore’s intestinal tract is three times its body length, an herbivore’s is twelve times its body length, and humans are closer to herbivores. Our digestion takes place without benefit of strong acids in the intestine, as carnivores have. Herbivores (and humans) chew their food before swallowing with grinding molars, whereas carnivores rip meat in chunks with incisors and swallow it whole. Herbivores

and humans get vitamin C from their diets, but carnivores make it internally.

Although it’s not likely that most humans will suddenly decide to become vegetarian, why not pay attention to the way human bodies actually work? Why can’t we share a few great vegetarian recipes with each other and decide to eat one-third less meat, or even just a tenth less? Albert Einstein, himself a vegetarian, believed that, “Nothing will benefit human health and increase the chances for survival of life on Earth as much as the evolution to a vegetarian diet.” And Thomas Jefferson, who lived to be eighty-three—pretty good for his day—ate meat “as a condiment to the vegetables which constitute my principal diet.” When we reduce the space allocated to billions of grazing, chewing, squealing, tail-swishing livestock (about twenty billion of them!), we’ll free space for other uses: open space or wilderness, which will make nature more resilient and humans healthier; the growing of cellulosic crops (maybe algae) for vehicle fuels; and a place for additional homes and communities, since world and U.S. populations continue to expand. With less meat in our diets, we’ll also use much less energy per capita (since nitrogen fertilizer is made from fossil fuel), generate far fewer greenhouse gases, and conserve water for more critical uses, such as drinking, sanitation, and the irrigation of fruits and vegetables.

We’re not meeting the need for water, either. Says physician and water expert Fereydoon Batmanghelidj, “People in industrialized countries aren’t sick, they’re thirsty!” He’s documented a link between dehydration and inflammation; heartburn; back, joint, and stomach problems; digestive difficulties; blood pressure problems; diabetes; depression; stress; and being overweight. Professor Friedrich Manz of the Research Institute of Child Nutrition in Dortmund, Germany, reports that students should be drinking 20 percent more water, because dehydration also causes an inability to focus. What’s the right amount to drink? Instead of counting glassfuls, Batmanghelidj counsels, “You can tell if you’ve had enough water, because your urine will be colorless.”9 A general rule of thumb is that 20 percent of the liquids we need come from food, and, in season, I can easily get that amount with just peaches and plums.

Why should it surprise us that our bodies require water? The human brain is 75 percent water; muscles, 75 percent; and even “bone-dry” bones are 22 percent water. Water is needed (in blood) to carry nutrients and oxygen to cells, and helps convert food into energy, remove waste, moisten oxygen for breathing, regulate body temperature, and—the grand finale—create life. But although the need for water is indisputable, the ability to continue to meet that need well is less certain. Water tables are falling throughout the world, reservoirs are filling up with silt, and our use of water

is often very careless, especially when subsidies keep costs artificially low in agriculture or industry.

But water is far from free; in my hometown, its price has jumped from $1.85 per thousand gallons to $3.85 in just the last six years. My neighbors and I feel very fortunate to have purchased water rights for our community garden in 2001—accessed from an irrigation ditch with a solar-powered pump—because our half-acre shared garden and orchard uses as much as half a million gallons of water every growing season—more than a thousand dollars of value at potable water prices.

While each American drinks a daily four to ten glasses of water and other beverages, the amount of water our food “drinks” in the fields and processing plants is more like 2,000 gallons a day. About an equal amount is used in the United States by the power industry to cool natural gas turbines as well as nuclear cooling towers. (In the broiling summer of 2006, nuclear plants in both the United States and Europe were forced to shut down because cooling water from ponds and rivers wasn’t cool enough to ensure safety.) So really, the best ways to conserve water are to pay attention to what we eat, and to use energy efficiently. It’s also very important to use water-efficient fixtures in the home, and landscaping that minimizes water use. The 100 gallons a day that we each use in our homes can easily be cut by a third to a half by substituting efficient conveyances—in the form of well-designed fixtures, showerheads, toilets, and aerators—for resources. The need for water will only get stronger, since the global populations continue to expand, but the amount of fresh water remains exactly the same.

The consumption of resources for tangible needs, such as lights, heating, mobility, food, and water, can be delivered with a higher level of ingenuity and more mindfulness about what result we are trying to achieve. When we choose the right size, the right time, and the right place for both devices and actions, saving resources becomes automatic. However, the way we meet intangible needs, such as affection, creativity, identity, and freedom, isn’t usually a question of engineering or design, but rather psychology and behavior. That makes them no less of a problem; if the intangible needs remain unmet, we cling to consumption and careless technologies as would-be pathways to satisfaction.