In a sense, experimental films represent an antigenre, in that they rarely follow “the rules” of commercial cinema, while mainstream films generally follow certain conventions. But in the 1920s, artists appropriated film as a working medium, using cameras and celluloid rather than paint and canvas. They created an art cinema, producing avant-garde works that might use purely abstract imagery or actors but generally eschewed narrative or conventional storytelling.

France, already a hotbed of modern art, was a cauldron of avant-garde filmmaking. In Cubist painter Fernand Léger’s Mechanical Ballet (1924), photographed by Man Ray and Dudley Murphy, and with a score by American composer George Antheil, inanimate objects “dance” with animation, while the humans depicted seem drained of life. René Clair’s Surrealist Entr’acte (1924) was screened between acts of Erik Satie’s ballet Relâche (also scored by Satie), with cameos by such luminaries as Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray (playing chess), Francis Picabia, and Satie himself. The film features an outrageous funeral procession, ending with the “corpse” rising from the dead and causing everyone at the funeral to disappear.

Russian émigré director Dimitri Kirsanoff, working in Paris, made one of the most powerful experimental films of the time, Ménilmontant (1926). Beautifully filmed, it also has a strong narrative: it begins with two sisters murdering their parents with an axe, then heading for Paris. There, a man seduces and impregnates the younger girl, then abandons her for her sister. It ends with his murder. New Yorker movie critic Pauline Kael told an interviewer that it was one of her favorite films.

Surely the most famous silent art film of all time is Luis Buñuel’s An Andalusian Dog (1928). The Spaniards Salvador Dalí and Buñuel collaborated on the script, and Buñuel shot the film in two weeks for a pittance (borrowed from his mother). A surreal montage of striking images—an eye being sliced by a razor, ants emerging from a hole in a hand—it haunts one’s imagination even today. Generations of film critics and writers have speculated about its “meaning.” Let’s let Buñuel have the last word. “Our only rule was very simple: No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted. We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why,” he wrote in his memoir, My Last Breath.

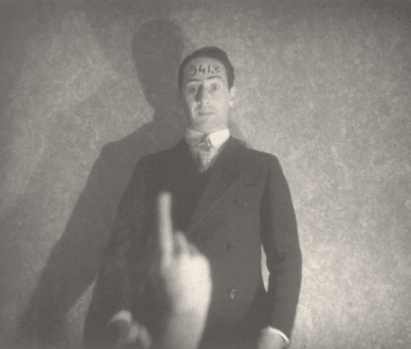

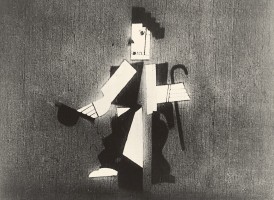

Robert Florey’s The Life and Death of 9413, a Hollywood Extra (1928), the story of the short and unhappy life of an extra in Hollywood who wears a number on his forehead for casting calls that never come. Only in heaven is he numberless.

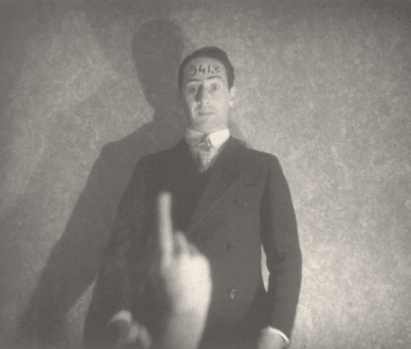

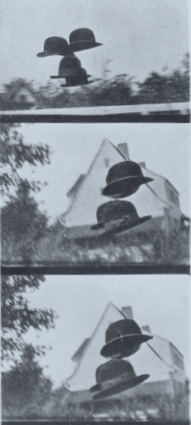

In Hans Richter’s Ghosts Before Breakfast (Vormittagsspuk, 1928), hats dance in an antic Dada experience.

France may have created myriad art films, but it certainly didn’t have a monopoly on experimental imagination. Americans also produced avant-garde works. An early example is Manhatta (1921), by photographer Paul Strand and painter and photographer Charles Sheeler. It depicts contemporary Manhattan as a cold forbidding place, using verses from the poetry of Walt Whitman as intertitles, sometimes ironically. Much of it is shot looking down from atop skyscrapers, their towering, abstract architecture giving its denizens and workers the likenesses of insects in a hive.

The Seashell and the Clergyman (La coquille et le clergyman, 1927), directed by Germaine Dulac and written by Antonin Artaud, contains a montage of a priest’s struggle to suppress his sexual desires.

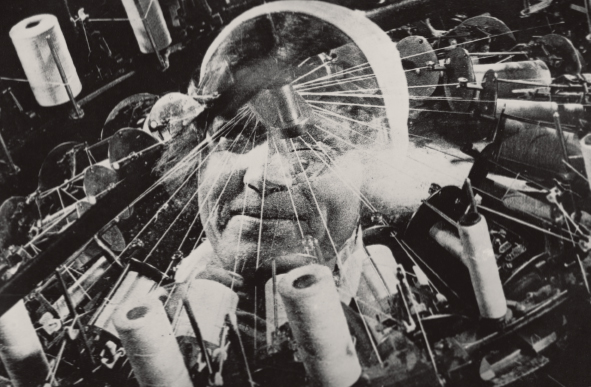

In Dziga Vertov’s The Man with a Movie Camera (Chelovek’s kinoapparatom, 1929), a cameraman travels around a city, documenting urban life from many angles and at dizzying speed.

Fernand Léger’s Mechanical Ballet (Charlot présent le ballet méchanique, France, 1924), photographed by Man Ray and Dudley Murphy, mixed inanimate objects with humans.

The Life and Death of 9413, a Hollywood Extra (1928) is a ninety-nine-dollar satire of the star system. Directed by Robert Florey and Slavko Vorkapich and photographed by Gregg Toland, it tells the story of an actor wannabe who is so dehumanized by the system of “auditions” that he has the number 9413 emblazoned on his forehead. In a parody of Hollywood happy endings, he eventually dies and goes to heaven. The film was made on a table, using cardboard, paper cutouts, kitchen utensils, and some live footage. Chaplin was enamored of it and it got some distribution in commercial theaters. Florey went on to direct more than sixty features, while Toland shot a little film called Citizen Kane.