LYNDA VAN DEVANTER WAS in her last year of nursing school in Baltimore, Maryland, when the war in Vietnam began to press into her consciousness.

“Those guys look so young,” she said one night to her roommate, Barbara, as the two watched the news about the war.

“Most of them are no more than eighteen or nineteen,” Barbara said.

Lynda began to research the war. She read that the United States was attempting to save South Vietnam from a Communist takeover by the North. “There were brave boys fighting and dying for democracy, and if our boys were being blown apart, then somebody better be over there putting them back together again,” she wrote later. “I started to think that maybe that somebody should be me.”

So when an army recruiter came to the nursing school in January 1968, both Lynda and Barbara were ready to sign up.

“Are you crazy?” asked Gina, their friend and fellow nursing student. “You go in the Army, they’ll send you to Vietnam. It’s dangerous over there.”

“I want to go to Vietnam,” answered Lynda simply.

“But what if you get killed?” Gina asked.

“The sergeant told us that nurses don’t get killed,” Barbara said. “They’re all in rear areas. The hospitals are perfectly safe.”

“I think you’re both nuts,” Gina said. “Leave the wars to the men.”

They ignored her advice, and after graduation Lynda and Barbara drove off to Fort Sam Houston, Texas, for their basic training. One activity they practiced repeatedly in training was what to do in a “mass-cal” (mass casualty) situation, when the hospital would be suddenly overwhelmed with wounded men.

During a mass-cal, the nurses would have to use something called triage. They would quickly assess each wounded man, then take one of three actions: (1) send him immediately to surgery; (2) have him wait his turn for surgery; or (3) ease his pain before allowing the inevitable to happen.

“Essentially, we were deciding who would live and who would die,” Lynda wrote later. It was a difficult concept for her since she had become a nurse to save lives. But her instructors made it clear that if precious time was spent on one hopeless case, those with survivable wounds might lose their chances.

On June 8, 1969, 1st Lieutenant Sharon Lane, a 26-year-old nurse from Ohio, became the first (and only) US Army nurse killed in Vietnam as a direct result of enemy fire. She had been sitting on a bed in her hooch—living quarters—when a VC rocket exploded nearby, sending shrapnel in every direction.

A few hours after Sharon’s death, the plane carrying Lynda and 350 men began its descent into South Vietnam. When the plane began “jerking wildly,” luggage fell from the overhead racks. Terrified, Lynda looked out the window. She could see explosions.

“Men,” said the voice of the pilot over the intercom, “we just came into a little old firefight back there and it looks like them V.C. ain’t taking too kindly to us droppin’ in on Tan Son Nhut. So we’re gonna take a little ride on over to Long Binh and see if we can’t get us a more hospitable welcome. Keep your seatbelts buckled and we’ll be down faster than you can say Vietnam sucks.”

Lynda was slightly reassured by his casual manner and then by their smooth landing in Long Binh. “But if there had ever been any cockiness in me before this trip began, there sure wasn’t any now,” she wrote later. “In its place was a cold, hard realization: I could die here.”

She spent the next few days at the 90th Replacement Detachment at Long Binh. Describing the area later, Lynda wrote, “Coiled barbed wire dominated the countryside, snaking its way up and down the roads, around the villages and through the fields. Guard towers rose high in the air, dwarfing all other structures. In each one, a soldier silently watched for Viet Cong, his M-16 rifle always at the ready.”

After being introduced to the nurses already working at the 90th, she asked them if the area was safe, given that everything looked so battle-ready.

“Safe?” laughed one. “Honey, whoever fed you that line should be horsewhipped.” She told Lynda that many nurses had already been wounded. She continued, “The V.C. don’t care whether you’re a nurse, a clerk, or an infantryman. All they know is that you’re an American.” And what made the situation particularly difficult, she said, was that the VC were essentially impossible to distinguish from the rest of the population.

Lynda’s destination was the 71st Evacuation Hospital in Pleiku Province, near the Cambodian border, an area of heavy combat. Lynda had heard that the casualties were “supposedly unending.”

Her first shift shocked her: “There were only fifteen wounded soldiers who needed surgery. I saw young boys with their arms and legs blown off, some with their guts hanging out, and others with ‘ordinary’ gunshot wounds.”

Lynda would remember her first few days in the operating room as “a blur of wounded soldiers, introductions to new colleagues and almost constant surgery during our twelve-hour shifts.” And what surprised her most was that everyone kept saying this was a “slow period.”

She began assisting a surgeon named Carl, who had a deserved reputation for saving lives in a near-miraculous manner. Carl could talk for hours on almost any topic and did so while performing surgeries. But when he became tired, the topic he returned to again and again was that his young patients were being shot to pieces for nothing.

Lynda begged to differ, telling him that “the war was a noble cause to preserve democracy,” something she believed was certainly worth fighting and dying for.

“You really believe that?” Carl asked her quietly.

“Of course I do,” she replied.

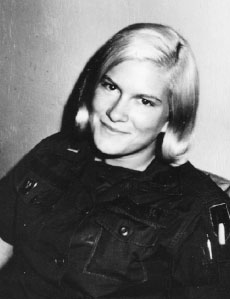

Lynda Van Devanter. Buckley family and personal archives of Lynda Van Devanter

“Is that why you always wear that rhinestone flag on the lapel of your fatigue shirt?”

“I think we should be proud of our country, Carl, and proud of our flag.”

“So do I. But I’m afraid this time, we may find that our country is wrong,” the surgeon said.

A week after arriving at the 71st Evacuation Hospital, Lynda attended a party at the Bastille—a large hooch that served as the hospital’s social center. Less than an hour into the party, she heard an explosion. The room went black. Lynda dove into a corner, shaking with fear. A loudspeaker outside blared, “Attention all personnel. Take cover. Pleiku air base is under rocket attack. Security alert condition red.”

Lynda was shocked to hear casual conversations: people discussing sports and patients. And as the flashes of the American return fire lit up the room, Lynda could see people dancing. She didn’t understand why they weren’t terrified.

When the siren stopped and everyone walked out of the party, she asked one of the medics, “How do you know it’s over?”

“Don’t worry,” he replied. “Once it stops, that’s it for the night. It never starts again. That’s the way the V.C. work. It’s all just harassment. They need target practice and we’ve got a nice red cross they can aim at.”

Apparently the VC had also taken aim near Lynda’s trailer. On her return from the party, she discovered an enormous crater only three feet away. The trailer’s walls were covered with holes made by pieces of hot shrapnel. Inside, Lynda noticed with a chill that the explosion had caused an enormous light fixture to fall from the ceiling onto her own cot.

That night she experienced a mass-cal for the first time. Describing it later, she wrote:

The moans and screams of so many wounded were mixed up with the shouted orders of doctors and nurses. One soldier vomited on my fatigues while I was inserting an IV needle into his arm. Another grabbed my hand and refused to let go. A blond infantry lieutenant begged me to give him enough morphine to kill him so he wouldn’t feel any more pain. A black sergeant went into a seizure and died while Carl and I were examining his small frag wound. “Duty, honor, country,” Carl said sarcastically as he worked. “I’d like to have Richard Nixon here for one week.”

Over the next three days, Lynda snatched bits of sleep whenever she could. She rarely knew if it was day or night. But when the mass-cal was over, Carl gave her the greatest compliment she could have wished for: “You’re a good help, Lynda.”

As they walked to the hooches, Lynda could hear the sound of guns and helicopters in the distance. She wondered how long it would be until the wounded of that battle would be brought to the 71st. The thought made her shudder.

Both too tired to sleep, Lynda and Carl talked for a long time, both “trying to sound philosophical about … death.” Lynda finally broke down, crying and shaking. Carl tried to comfort her and wound up crying too.

“Why do they have to die, Carl?” Lynda asked.

“Who knows?” he replied.

“I don’t understand,” she said.

“Nobody does,” he said.

But Lynda still felt proud of her country. Writing to her parents, she said:

At 4:16 a.m. our time the other day, two of our fellow Americans landed on the moon. At that precise moment, Pleiku Air Force Base … sent up a whole skyful of flares—white, red, and green. It was as if they were daring the surrounding North Vietnamese Army to try and tackle such a great nation. As we watched it, we couldn’t speak at all. The pride in our country filled us to the point that many had tears in their eyes.

It hurts so much sometimes to see the paper full of demonstrators, especially people burning the flag. Fight fire with fire, we ask here. Display the flag, Mom and Dad, please, everyday. And tell your friends to do the same. It means so much to us to know we’re supported, to know not everyone feels we’re making a mistake being here.

Every day we see more and more why we’re here. When a whole Montagnard village comes in after being bombed and terrorized by Charlie, you know. There are helpless people dying everyday. The worst of it is the children. Little baby-sans being brutally maimed and killed. They’ve never hurt anyone.

One harmless civilian who lived in the area was Father Bergeron. He was a funny, kindhearted French priest who was full of stories and did all he could to ease the suffering around him. Because of his selflessness, the 71st staff bent the rules for him. For instance, they were only supposed to treat civilians with war-related wounds. But when Father Bergeron brought them civilians with diseases, such as a young girl with congestive heart failure, they couldn’t refuse to help.

Father Bergeron hated the war. “Let the old glory mongers and politicians fight their own wars and let the young men and women get on with their lives,” he would often say. He absolutely refused to take sides; his only aim was to help as many people as he could. Lynda assumed the VC loved him as much as the staff at the 71st did.

Lynda, February 1970. Buckley family and personal archives of Lynda Van Devanter

It became brutally obvious one day that this was not the case. The 71st staff learned that the VC had tortured and killed Father Bergeron before displaying his remains in the middle of a village “as a warning to any American sympathizers.”

That night Lynda was assisting a surgeon working to save the life of an enemy prisoner. When the surgeon spoke of getting even by doing to his patient exactly what the enemy had done to the beloved priest, Lynda knew he was just venting and would never actually do anything so barbaric. But something welling up inside her almost wished he would. In that dark moment, she felt she might have gladly assisted him.

Lynda had to work harder now to remind herself that she was “in Vietnam to save people who were threatened by tyranny.” But she found that belief increasingly difficult to maintain as she “heard stories of corrupt South Vietnamese officials, US Army atrocities, and a population who wanted nothing more than to be left alone so they could return to farming their land.”

In her letters home, she began to express her doubts about how the United States was handling the war: “It would be a lot easier if our government would just make up its mind…. We should either pull out of Vietnam or hit the hell out of the NVA. This business of pussyfooting around is doing nothing but harm. It’s hurting our GIs, the people back home, and our image abroad.”

Yet in the same letter, she admitted to being proud of her work: “I don’t think there are many other places where you can feel as needed in nursing…. For the first time in my life, I feel like I have to keep going or people might not survive.”

But the work was also taking its toll. “Holding the hand of one dying boy could age a person ten years,” she wrote later. “Holding dozens of hands could thrust a person past senility in a matter of weeks.”

Lynda discovered that she could no longer cry, which made her work somewhat easier. “If you can’t feel, you can’t be hurt,” she wrote. “If you can’t be hurt, you’ll survive.”

That all changed drastically a few months later when Lynda was in an officer’s club with some friends watching a United Service Organizations (USO) show. While in the middle of her second drink, she imagined she saw the faces and bodies of the wounded, dying, and dead men she’d seen at the 71st, all of them appearing in heartbreaking detail in her mind.

“They were all with me in that room,” she recalled later. “I tried to force them out of my mind. For a moment I did. Then all the images came crashing back on me.”

She became hysterical and was escorted back to her hooch. A fellow nurse stayed with her all night, holding her, rocking her. Finally, around 5:00 in the morning, she fell asleep.

When she woke 24 hours later, Lynda felt numb. She threw away her rhinestone flag pin and went back to work.

In June 1970, when her yearlong tour was up, Lynda boarded a jet, her “freedom flight” out of Vietnam. “As the jet took off, I was filled with the most exhilarating sensation of my life … like the weight of a million years had been suddenly lifted from my shoulders,” she said.

But when the bus from the airport dropped her and others off at the Oakland Army Terminal at 5:00 AM, they had no way of immediately reaching the San Francisco International airport, which was 20 miles away. Lynda decided to hitchhike her way there.

Dressed in her uniform, she watched car after car whiz by. Some of the drivers screamed obscenities at her. Others threw garbage. Finally, two friendly young men in a van stopped and offered her a ride. Relieved, Lynda tried to swing her duffle bag into the vehicle. Before she could do so, one of the men slammed the door shut.

“We’re going past the airport, sucker, but we don’t take Army pigs,” he said. Then he spit on her, called her a Nazi, and drove away, the back wheels of the van showering her with dirt and stones.

“What had I done to him?” Lynda wondered. “Didn’t they realize that those of us who had seen the war firsthand were probably more antiwar than they were? That we had seen friends suffer and die? That we had seen children destroyed? That we had seen futures crushed? Were they that naïve?”

Someone finally took pity on her, and eventually she made it back home to Virginia. On the first night she presented her family with a slide show of Vietnam photos. When she came to photos of the operating room, her uncomfortable parents asked if she could show them something “less gruesome.” Lynda hid the slides away in the back of her closet. “I had learned quickly,” she wrote later. “Vietnam would never be socially acceptable.”

Years passed, and Lynda took a series of nursing jobs while suffering an intense emotional pain she couldn’t shake or even begin to comprehend.

She eventually married a close friend who created a radio documentary called Coming Home, Again, relating Vietnam veterans’ experiences. One of the men involved in her husband’s project asked Lynda if she would agree to be interviewed for the documentary. Then he asked her to create the Vietnam Veterans of America (VVA) Women Veterans organization, to reach out to women veterans.

Lynda agreed. She also began studying post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and realized it had been part of her life for years. She was certain that many other women veterans were also suffering from PTSD. Her Women Veterans project gave a voice to these women and helped them realize they were not alone.

She became the first American Vietnam military nurse to publish a widely read war memoir; her book, titled Home Before Morning, helped inspire the creation of China Beach, an award-winning TV series set in an American evacuation hospital during the Vietnam War.

The VVA honored her in 1982 with its Excellence in the Arts award and in 2002 with its Commendation Medal.

Lynda suffered from a vascular disease she believed was related to Agent Orange, a defoliant used by the US forces during the war.

She died at age 55 on November 15, 2002, and her death was widely mourned within the Vietnam veteran community. “Lynda’s book stands as one of the most powerful, evocative, and influential Vietnam War memoirs,” said Marc Leepson, the arts editor of the VVA’s national newspaper, in an obituary for her. “Home Before Morning changed people’s attitudes about the women who served in the Vietnam War, especially the nurses who faced the brutality of the war every day and whose service was all but ignored during the war and in the years immediately after.”

Because Communist forces found cover under the lush vegetation growing in Vietnam during the war, the US military decided to destroy that cover by spraying it with powerful plant-killing defoliants—millions of gallons’ worth. The most widely used of these was Agent Orange, so named because of the orange band around its storage barrels. Agent Orange was extremely successful in clearing ground cover, but it caused severe damage to everyone who came near it, both in the short and long term: Millions of Vietnamese and Americans who were exposed to Agent Orange later gave birth to or fathered children with severe disabilities. A similar number of veterans on both sides of the war developed fatal illnesses years later from their previous contact with the poisonous substance.

American Daughter Gone to War by Winnie Smith (Gallery Books, 1994).

Dreams That Blister Sleep: A Nurse in Vietnam by Sharon Grant Wildwind (River Books, 1999).

Home Before Morning: The Story of an Army Nurse in Vietnam by Lynda Van Devanter with Christopher Morgan (Beaufort Books, 1983).