IN MARCH 1967, 23-YEAR-OLD New Zealand-born Kate Webb left her job in a Sydney, Australia, newsroom and headed for Vietnam. Why? “It was simply the biggest story going, and I didn’t understand it,” she wrote. Neither did Kate understand why, when Australia and New Zealand were sending their young men to fight in the war, their news agencies weren’t also sending reporters there.

So she went, taking with her only a typewriter, the name of a United Press International (UPI) photographer, and a few hundred dollars.

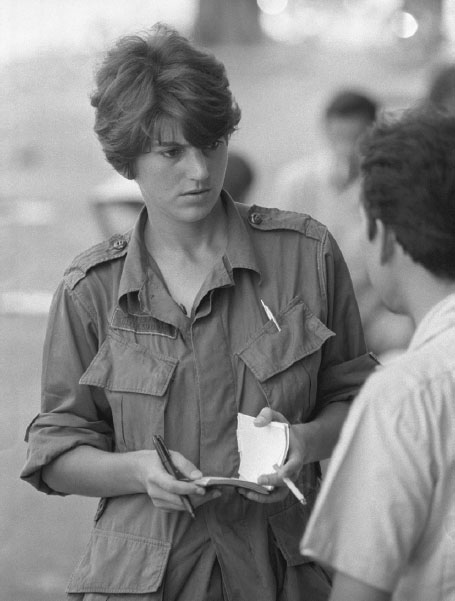

Writing articles for Vietnamese newspapers for a few weeks brought in enough income to prevent Kate from starvation but not from becoming “seriously hungry.” What’s more, news agency editors constantly rebuffed her, sometimes, she guessed, because she looked much younger than she was. The time on her visa was running out, and she was no closer to understanding the war than she had been before leaving Australia.

Then Kate got a “stringing,” or freelance, job with a GI newspaper. This gave her formal accreditation with the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), an extended visa, the right to attend daily military briefings, and the right to accompany the fighting men into battle.

She was gaining an understanding of Saigon—its journalists, priests, bar girls, and street kids—but she wanted to learn more about the war itself. Months later, she did. The war—and the Vietnamese Communist fighters—came to that city in a big way. On January 30, 1968, Kate rushed to the besieged American embassy in Saigon to cover the Tet Offensive, becoming the first wire correspondent to do so. Her articles appeared in the New York Times, Newsweek, and Time. And Kate was glad to discover that she possessed a crucial trait for a war correspondent: she could “function and write amid the knife-edge fear of battle.”

As Kate’s options widened, she was free to pursue stories that interested her. She decided to spend time with Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) soldiers. She knew that American papers, intensely interested in their own “political clamor over the war,” wouldn’t likely be publishing her stories of these South Vietnamese soldiers. But she went with the soldiers anyway because they were one aspect of the war she didn’t yet fully understand.

Kate knew that while the Americans could go home after their yearlong tours of duty, ARVN soldiers were required to remain in the war for its duration. For these men, the “dragging war usually spelled dishonor, death, injury, or imprisonment,” she wrote. She followed them on their “pitch-black” night patrols, her way lit only by “the tiny phosphorous mark on the pack of the man in front” of her. They laughed at Kate’s height—five feet seven inches—and her size-eight boots. But they also appreciated her because she did all she could to help them: unlike the Americans, these men didn’t have medical helicopter support. She helped them carry their wounded out of danger.

Kate’s curiosity eventually led her to Cambodia. That nation was “engulfed in chaos and on the bum end of a war the United States was pulling out of with a final, wrenching kick,” she wrote.

Nixon’s attempt to bomb Vietnamese Communist sanctuaries across the Vietnam border in Cambodia had stirred up deep and desperate trouble within that country. On March 18, 1970, Cambodia’s prime minister, Lon Nol, deposed Prince Norodom Sihanouk in a coup and established the Khmer Republic in Cambodia, which allied itself with the United States and sought to rid Cambodia of the Vietnamese Communists.

But Lon Nol had to fight another enemy, one emerging from his own nation: the Khmer Rouge, Cambodian Communists led by an intensely brutal leader named Pol Pot. The United States, in its quest to bomb the Vietnamese out of Cambodia, was also killing thousands of Cambodian civilians. Pol Pot used this destruction to stir up civilian hatred for the Americans—and for Lon Nol, a US ally. A civil war was born, and the Khmer Rouge—allied with the Vietnamese Communists—was on the rise.

The international press covered this civil war, regrouping every night in Cambodia’s capital city of Phnom Penh. On the evening of October 28, 1970, Kate’s UPI colleagues Frank Frosch—UPI’s bureau chief in Cambodia—and Kyoichi Sawada—a Pulitzer Prize–winning photographer—didn’t return. Their bodies were discovered the following day in a rice paddy next to a road referred to as Highway 2. Soldiers of the Khmer Rouge had executed the men; the Khmer Rouge never took prisoners. When a TV crew tried to film the bodies of the two men in the morgue, Kate lost control and tried to smash their cameras. When she was alone and calmer, she kept repeating one word to herself: “No.”

This tragedy gave Kate a new job: Frank Frosch’s. While Frank and Kyoichi had been alive, the three of them had spent many evenings in the UPI bungalow sitting below a huge map of Cambodia, discussing their day’s work. Now Kate spent hours alone in the same spot staring at the map, as if doing so would help her make sense of the war.

Months later, on the night of April 6, 1971, Chea Ho, a Cambodian freelance reporter, joined her. He pointed to an area along Highway 4 where he said there would be fighting on the following day between Cambodian Lon Nol paratroopers and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers. He showed her how far the paratroopers hoped to go. He said he was going there to see for himself whether they would make it that far.

Was Kate interested? She told him she wasn’t. But the following day, when she attended a military briefing and heard Chea Ho’s story repeated, she knew she had to see how well the Lon Nol paratroopers would perform.

Taking with her a Cambodian translator named Chhim Sarath (whom she called Chhimmy), Kate drove to the rear lines of battle and continued to the front on foot. A half hour later, she and Chhimmy found themselves trapped when “fire burst from all sides.” They huddled in a roadside ditch as bullets flew above them. As they crawled through the red dirt, they were eventually joined by four other trapped noncombatants: Tea Kim Heang, a Cambodian photographer; Eang Charoon, a Cambodian newspaper photographer and cartoonist; Toshiishi Suzuki, a Japanese journalist; and Vorn, Toshiishi’s Cambodian interpreter.

The fight was over. The Cambodian soldiers were gone. The NVA soldiers remained. The civilians tried to quickly put as much distance as possible between themselves and the former battleground. They crawled for hours, suffering increasingly from thirst, insect bites, and scratches from the sharp elephant grass. Thirteen hours later, Kate wrote one last entry in the journal she kept: “April 8, 0200. This nightmare is stretching out too long. Gone past unbearable.”

Later that morning, it would become much worse.

The civilians came face-to-face with two young men in NVA uniforms who motioned for the group to drop everything. Terrified, their hands in the air, the civilians all cried out, “Nha bao” (journalist), then “Nuoc” (water).

The soldiers stripped the civilians of their belongings, tied their hands behind them with baling wire that cut into their skin, linked them together into two groups of three, then moved them into a dark bunker. Kate assumed a live grenade would follow.

But she and the others were then brought back outside. It seemed the soldiers weren’t sure what to do with them. A soldier handed Kate a small tin of water. Thinking they would all share it, she passed it around before taking a drink. It came back to her empty. “That the others hadn’t left me anything, and what it meant, shocked me more than the rifles,” she wrote later. “I said nothing, but there was a huge loneliness in my head that didn’t leave me.”

Still tied together, the group was forced to march. “I tasted it—the feeling of being a prisoner—underneath the burning thirst, the new loneliness in me,” Kate wrote. And though she was certain they were going to be killed, she couldn’t resist her reporter’s “compulsive documenting of every detail” of her experience.

The soldiers hacked off tree branches, then placed them into the bound hands of the prisoners to keep them camouflaged from any passing planes.

Heading north, they “slipped like shadows through the villages and jungles, across paddy fields, and over mountains and small mountain streams, starting at dusk and stopping just before dawn.”

After a blurred number of days and nights on foot, the prisoners and their captors stopped in a clearing. One by one, the soldiers singled out each prisoner for what they said were interviews. Thirty or forty minutes would pass, then a single shot would be heard. “As our numbers dwindled, we couldn’t meet one another’s eyes,” Kate wrote later.

Her turn came. She was brought to a military man roughly in his 60s. Ever since her capture, Kate had been striving to view herself as more than a frightened prisoner and the group of them more than a herd of doomed cattle. Now, sitting before this military man, exhausted and ill though he appeared, Kate’s hands shook with fear. She forced herself to remember that she was a respected journalist and the representative of an international news service.

“Do not be afraid,” said the expressionless interpreter. “You are in the hands of the Liberation Armed Forces [the army of the Southern Vietnamese Communists].” The interpreter told Kate to speak slowly so that he could understand her English. He asked her for her name, rank, and nationality. She gave her name and nationality but no rank, insisting that she wasn’t part of the military. She measured each word with great care.

The questions droned on and on. The interviewer asked about her family, what each member did for a living, and how much each was paid. Finally, he came to the point.

“Why were you down on Highway 4?”

“To find out what was happening,” Kate replied.

“Why would you risk your life to find out what was happening?”

“Now I wish I hadn’t but I am a reporter.”

“Why were you with the Lon Nol Troops?”

“I wasn’t with them,” Kate answered, explaining that she had followed them in her own car.

He asked what she thought of the war. Kate said it was “too long.” He asked why it was so long, and Kate responded that the different groups of people could not agree on what was most important.

“An odd thing happened as question followed question and the young interpreter struggled to translate from English,” she wrote later. “I found myself thinking of the senior officer interrogating me as a professional soldier. The flip side of that was that I stopped feeling like a filthy, scared prisoner from the other side … probably on my way to execution, and like a professional reporter instead. He was taking what the war dealt out to him, and I was taking what the war dealt out to me.”

When the interview was over, Kate was led down a narrow path. To her surprise, it led to a clearing where she found the rest of the prisoners, all of them very much alive.

The marching resumed until they stopped at a shelter near a military complex days later. The soldiers interrogated the prisoners again and gave what Kate described as “history lessons”: the war from the Communist point of view.

By this time, the prisoners’ health was in a precarious state. Everyone had lost too much weight. And Kate was experiencing severe symptoms: vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and shivering.

But what disturbed her more than her deteriorating physical condition was what was happening to her mind and emotions. Living inside “the gray limbo of the prisoner … with no links to the living world” made her fear she was descending into a dark place.

Three simple events had a surprisingly positive effect on Kate’s dangerous psychological state. One day she abruptly decided to stand on her head. This simple act—along with the astonished reaction of everyone around her—raised her spirits profoundly.

The second event occurred after her return from a daylong interrogation. Toshiishi sat Kate down under a tree and led her through the steps of a Japanese tea ceremony using an empty condensed milk can.

Then one morning Kate was struck by the profound but simple beauty of “dawn reflected upside down in a dewdrop hanging from a leaf.”

Finally, following a “tense new round of interrogations” at the same location, the soldiers told the prisoners they were being released. Kate didn’t allow herself to believe it. “Hope, we had fast learned, was as treacherous as an oasis mirage, and as cruel,” she said.

The prisoners were taken to the command hut. Every soldier and officer seemed to be there. The prisoners sat down on wooden benches in a semicircle around a table. An officer stood behind the table and began to read from a piece of paper, an official document that had apparently been translated into English. Kate was so ill at this point she had trouble concentrating on his exact words, but the officer appeared to be announcing their release. When he was finished, the prisoners were given a signal to clap. They clapped. They were each directed to sign the statement before their belongings were returned to them, minus notes and photographs. These, they were told, had been “liberated.”

Then began what Kate called the “Mad Hatter’s tea party.” Tea was served, along with bananas, candy, and cigarettes. The hungry guards, Kate recalled, “hogged into the candy with more gusto” than the prisoners did. The captors asked the prisoners if they wanted to make thank-you statements into a tape recorder for their “humane treatment.” As they hadn’t been actually tortured, four of the prisoners, including Kate, agreed.

Then they were off with six guards. On the way, one of the guards repeatedly discussed the release plans with Toshiishi and Kate. It was a dangerous situation for all of them, the guards included, because they would be walking out of NVA- and Vietcong-controlled territory. Kate wondered why these Communists were risking the lives of six of their men in order to release the captives.

After two days, she woke in the middle of the night to see everyone scrambling to gather their things. Then, amid hasty good-bye handshakes, the guards left their prisoners, who now “stood alone in the dark on a roadside in no-man’s land.” Terrified without their guards, the former prisoners eventually walked toward a group of Lon Nol soldiers and officers. Kate—in front of the group so they would seem less threatening—waved a white piece of parachute material the Vietnamese captors had given her, and they all yelled, “Kassat, kassat” (press, press).

They had been in captivity for 23 days.

“Miss Webb,” cried one officer, recognizing Kate, “you’re supposed to be dead!” Kate had been assumed dead because everyone thought the Khmer Rouge had captured her and someone had discovered the body of a woman resembling her.

As she recovered from two types of malaria, Kate’s transition from captivity to freedom was perhaps the strangest and in some ways the most difficult aspect of her experience. Aside from receiving a “bizarre mixture of fan and hate mail,” she realized that her communication skills had fundamentally altered. Although she was free, she found herself choosing each word with the utmost care, as if her survival, and that of those around her, still depended on it.

Something else she found quite disturbing was the deeply divided US press. She was shocked when, speaking to the members of the Washington Press Club, she was told that “a field reporter was morally bound to take a hawk [prowar] or dove [propeace] stand.”

Kate argued that the field reporter’s job was not to choose sides but only to report “what was happening and what people were saying, feeling, and doing on the ground. Without that hard, unbiased input,” she said, there was “nothing to opinionate, or stand, on.”

When the Vietnam War ended, Kate noted that many of its reporters had trouble coping with peacetime: “There were suicides and divorces, a lot of editors saying what do we do with these madmen, and quite a few of us madmen not knowing what to do with ourselves.”

But she continued to work as a journalist, often facing dangerous situations to do so. While covering the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, she was nearly scalped when a militiaman dragged her up a flight of stairs by her hair. And while covering the assassination of India’s former prime minister Rajiv Gandhi, she almost lost an arm during a motorcycle accident.

Kate died from cancer in Sydney, Australia, on May 13, 2007, at age 64. Her New York Times obituary quoted a fellow Vietnam reporter, Pulitzer Prize–winning Peter Arnette, who said that Kate was a “fearless action reporter” and “one of the earliest—and best—women correspondents of the Vietnam War.”

“Highpockets” by Kate Webb, in War Torn: Stories of War from the Women Reporters Who Covered Vietnam by Tad Bartimus et al. (Random House, 2002).

On the Other Side: 23 Days with the Vietcong by Kate Webb (Quadrangle Books, 1972).