JOAN BAEZ WAS AT THE White House. A rising star of the folk music movement, she had been invited to perform there, with several other entertainers, in a gala for President John F. Kennedy. But the president had been shot before the performance date. Shortly after his shocking assassination in November 1963, Joan received a message from the staff of the new president, former vice president Lyndon B. Johnson, assuring her that the gala would go on as planned.

She went, dedicating one of her songs to Jacqueline Kennedy, the former First Lady. Then, before singing “The Times They Are a-Changin’,” a new Bob Dylan song, she pleaded with President Johnson to keep Americans out of Vietnam.

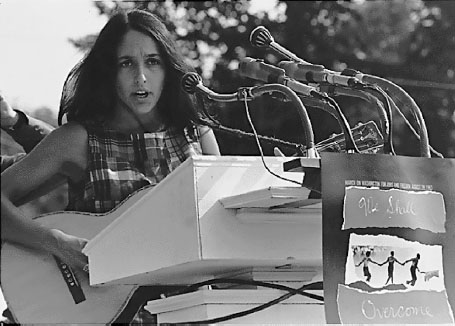

Joan already knew how to use her beautiful singing voice to promote causes she believed in. Earlier that year, on August 28, 1963, she had sung “We Shall Overcome,” the civil rights movement anthem, in DC at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom before her good friend Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

After Joan’s successful appearance at the presidential gala, a representative from Young Democrats for Johnson asked her to be one of their spokespeople. President Johnson was eager to win the 1964 election, to prove he could become president in his own right. He wanted Joan’s help.

She responded to President Johnson directly, writing him that she would consider the offer only if he would “quit meddling around in Southeast Asia.” The Young Democrats for Johnson didn’t call again.

Joan would indeed have a powerful influence on young men and women, but not in the way President Johnson had hoped. Although he wanted his legacy to be the Great Society—a series of laws attempting to eliminate poverty and racial injustice in the United States—he would instead be remembered as the American president most responsible for escalating US involvement in the Vietnam War. And Joan would be remembered for being one of that war’s most prominent opponents.

Joan at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Wikimedia Commons

After Johnson won the 1964 election, Joan had “a quiet revelation.” Realizing that the US involvement in Vietnam was going to end up a “disaster,” she decided to make a symbolic gesture of protest. Since approximately 60 percent of the national budget at that time went to the military, Joan refused to pay 60 percent of her federal income taxes. She wrote a lengthy letter to the IRS—and released it to the press—informing them of her plan and explaining in great detail why she could not support the manufacture of weapons of war. Not only did the weapons destroy lives, she wrote, but also the United States was spending far too much of its budget on the war. Newspapers across the country published the letter.

When an IRS official threatened Joan with jail time for tax evasion, she shrugged, saying, “Well, I imagine I’ll go to jail sometime. It might as well be over something I really believe in.”

“But jail’s for bad people!” the IRS official cried.

“You mean like Jesus?” replied Joan, smiling. “And Gandhi?”

Joan would go to jail—twice in 1967 for protesting the war directly outside of the Oakland, California, military draft induction center—but never for income tax evasion, although she continued to pay only 40 percent of her federal income tax for the next 10 years. The IRS decided to get the other 60 percent by sending their agents to her concerts to take money from the concert register. Joan didn’t mind. At least she wasn’t giving it to them willingly: they had to spend their own time and effort to get it.

Her growing notoriety resulted in frequent invitations to appear on TV talk shows. The hosts would often invite her to appear along with someone who was anti-Communist and enthusiastic about America’s involvement in Vietnam. Joan would take these opportunities to appeal directly to the mothers in the live studio audience. She’d ask them about the busses arriving at the induction centers each morning. Were they “filled with young men ready to give their lives for their country,” she asked, or were those new draftees merely “young boys who were terrified and were there only because they’d gotten a letter in the mail telling them they had no choice”?

Prior to 1967, prowar songs such as “Hello Vietnam,” “Dear Uncle Sam,” and “The Ballad of the Green Berets” actually outnumbered antiwar songs broadcast on American radio. Popular songs such as “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” “Eve of Destruction,” and “Masters of War” (the last two written in the early 1960s to protest the Cold War’s nuclear arms buildup) became widely used by antiwar protestors later in the decade. As the war progressed and the protest movement gained momentum, some artists wrote and released songs—such as “I Ain’t Marching Anymore” and “Universal Soldier”—that could be heard more often at protest rallies and coffeehouses than on the radio because some stations banned them.

Though it was not written as a protest song, “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” eventually became an anthem of the American fighting men in Vietnam, who frequently requested it of the bands hired to entertain them. They also loved the protest song “Fortunate Son,” a complaint about how wealthy young men could often avoid being sent to Vietnam.

“Give Peace a Chance,” arguably the most famous protest song of the war, was both played on the radio and sung at protest rallies: in November 1969, it was sung by hundreds of thousands of people who had gathered for an antiwar protest in Washington, DC.

But Joan wanted to do more. And she wanted to learn more. While her instincts had led her to become a major voice in the antiwar movement, she wanted to gain a more solid academic and historical foundation of the concepts of peaceful protest. So in 1965 she and her friend and mentor Ira Sandperl began an organization called the Institute for the Study of Nonviolence. Joan purchased a building in Carmel Valley, California, and charged attending students nominal fees, provided them with reading lists, encouraged them to meditate and engage in discussions, and invited them to attend lectures and seminars from peace activists and speakers from all over the world.

The institute also helped young men in need of moral support if they chose to oppose their own military drafts. One young man named Billy, who had been corresponding with Joan for four months, had finally decided to go AWOL (absent without leave) from the army. He visited Joan before he turned himself in to the military authorities.

He told her that during his training he and other draftees had been brought into a chapel and told that, although one of the Bible’s 10 Commandments was “Do not kill,” the military was going to teach them how to do just that. The trainer asked the young men if that was right. Before they could answer the question, he did: “Yes, it’s right to kill because you’re killing for your country!”

Billy had prepared a statement to hand to the military authorities, part of which read, “I will not bring myself to bear down and fire with intent to kill another human being. I do not call myself a good, pure Christian person, my life has shown that I am not. But I found peace in myself with God in denying to kill.”

After working nearly full-time at the institute for a few years, Joan opened a branch of Amnesty International—a human rights organization—on the West Coast before she resumed a hectic schedule of concerts.

She was on the road in December 1972 when she received an opportunity to take a closer look at the war she had been protesting for so long. Cora Weiss, a leader of the Women Strike for Peace (WSP)—an organization begun in 1961 to protest nuclear testing and later also to try to end US involvement in Vietnam—said WSP was organizing trips for Americans to Hanoi, the capital of North Vietnam, in an attempt to create friendly relationships between American and North Vietnamese civilians. Would Joan like to go?

Joan agreed and was soon on a plane with three American men: lawyer and ex–brigadier general Telford Taylor; Episcopalian minister Rev. Michael Allen; and Barry Romo, a Vietnam veteran who was now against the war.

Their tour was carefully designed to show these four Americans the damage their military had inflicted on the people of North Vietnam. On the first day, Joan took an opportunity to speak to her tour guide about the ideals of nonviolence, saying that the Vietminh resistance had at one point been a peaceful movement. The guide laughed. Nonviolence was not appropriate in this war, he said.

On the first evening after dinner, the Americans were treated to some Vietnamese songs. Joan sang as well, dedicating her performance of “Sam Stone”—a song about a drug-addicted veteran—to all the people from both sides who had died in the war. Barry wept through her entire performance. The Vietnamese people at the dinner surrounded him in a protective way, as if, Joan thought, they were trying to shield him from further pain and let him know that they had forgiven him for his part in the war.

During the next two days, the North Vietnamese showed their American visitors propaganda films and photos of dead civilians and gave long lectures on what specific areas the American military had bombed. Since Joan had long been protesting the war, she was annoyed with these enforced activities and longed to explore Hanoi on her own.

On the third evening, December 18, she was feeling sick from watching yet another graphic propaganda film and was about to retire to her room for the night when the electricity in the building failed. Two long, loud sirens rang out. One of the Vietnamese men excused himself calmly, saying it was an “alert.”

All the hotel guests walked toward a nearby bomb shelter. Because everyone seemed so relaxed, Joan thought she must be the only nervous one in the group. Then she heard the roar of planes. Everyone jumped and ran down the narrow flight of stairs. An explosion shook the walls.

When the bombing stopped, someone joked that, because it was December, perhaps the raid was an early Christmas present to Hanoi from President Nixon. Everyone laughed. But this series of raids—technically referred to as Operation Linebacker II and specifically designed to intimidate the North into recommencing peace talks—would actually become known as the Christmas Bombings.

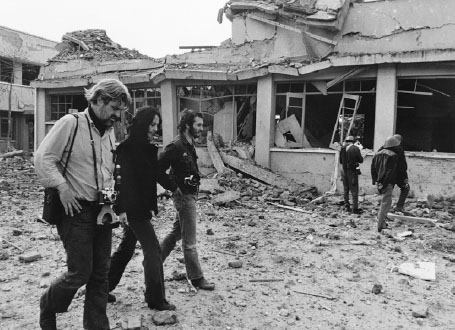

Ten more bombing raids occurred that night. In the morning, the Americans walked through a demolished village on the outskirts of Hanoi. Large craters were everywhere. Joan saw people hunting through the wreckage, apparently looking for lost items. One girl bitterly asked Joan and the other Americans if they were there to “look at Nixon’s peace.”

Left to right: Rev. Michael Allen, Joan Baez, and Barry Romo walking through Hanoi’s international airport after American B-52 airplanes had bombed it. Getty Images

Ten tense nights of bombing followed (with the exception of Christmas Day), and each morning, the Americans were invited to view the damage created the night before. When Joan saw a bombed hospital and a dead elderly woman laid out on the street, she broke down and sobbed uncontrollably.

During one raid, sophisticated Soviet antiaircraft guns and missiles shot down six American flyers. Bandaged and in shock, the American prisoners were forced to participate in a press conference. They each identified themselves and were allowed to give a message to the American press. One called the war “terrible” and said he hoped it would “end real soon.” Considering the damage the raids had caused, Joan thought the North Vietnamese conducted the press conference with amazing self-control.

But on the following night, she discovered that this restraint had a cruel edge. The Vietnamese were treating the prisoners inhumanely, including not allowing them into a shelter during the next raid. Instead the prisoners remained in their shoddy prison bunkhouses, which US bombs had already partially destroyed. Joan and the other Americans went to visit them. The prisoners seemed frightened and confused. One of them showed Joan a large piece of shrapnel that had come through the barracks ceiling. He asked her what was happening.

Joan, surprised by the question, explained with a bit of sarcasm how the American bombings were causing this type of damage.

“What I mean is, Kissinger said peace was at hand, isn’t that what he said?” the POW asked.

Joan’s sarcasm disappeared. She wanted to cry.

“That’s what he said,” she replied. “Maybe he didn’t mean it.”

Then she asked them if they’d like her to sing. They requested “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” Joan’s most recent hit, a song about the Civil War from the Confederate perspective. She sang it. Then they all sang “Kumbaya” before Joan embraced each prisoner and left for the safety of the bomb shelter.

One morning after a particularly damaging bombing raid, the Vietnamese took Joan to a devastated area. There a woman stood where her home had once been. She was crying, repeating the same phrase over and over. Joan asked for an interpreter. The woman was crying, “My son, my son. Where are you now, my son?”

When Joan returned to the United States, she distilled 15 hours of recordings she had made during her trip—Vietnamese warning sirens, American bombing raids, her own singing in the bomb shelter, and the laughter of Vietnamese children—into a new album. She dedicated her unusual new record to the Vietnamese people and called it Where Are You Now, My Son?

In 1979, five years after the United States had withdrawn from Vietnam, Joan spoke out publicly against the new Socialist Republic of Vietnam. In a letter published in four major US newspapers, she criticized the brutal reeducation centers that were forcing a Communist worldview upon the people of South Vietnam. She wrote, “Instead of bringing hope and reconciliation to war-torn Vietnam, your government has created a painful nightmare.” She maintained that her new protest was perfectly consistent with her previous antiwar stance, saying, “My politics have not changed. I have always spoken for the oppressed people of Vietnam who could not speak for themselves.”

Throughout the years and to this day, Joan has continued to lend her support for causes she believes in strongly, always accompanied by her singing and always in a manner that promotes the fundamentals of nonviolence. In August 2009 she again affirmed her commitment to peace. Before giving a concert in Idaho Falls, Idaho, she was told there were four Vietnam veterans outside protesting her appearance.

She immediately went outside to meet them. One was holding a sign that read, JOAN BAEZ GAVE COMFORT & AID TO OUR ENEMY IN VIETNAM & ENCOURAGED THEM TO KILL AMERICANS!

The veterans told her that decades earlier they had felt betrayed and hurt by American antiwar protestors who had lashed out at the servicemen upon their return from Vietnam. Joan listened to them quietly and then explained that she had never engaged in that sort of abuse, that she had always supported Vietnam veterans.

Her sincere friendliness diffused their anger, and before long, they asked her to sign their posters. She agreed to sign the backs, not the fronts, where the denigrating words were printed.

Later, during the concert, Joan dedicated a song to the veterans she had just met. “You know, they just wanted to be heard,” she explained. “Everyone wants to be heard. I feel like I made four new friends tonight.”

And a Voice to Sing With: A Memoir by Joan Baez (Summit Books, 1987).

Daybreak by Joan Baez (Dial, 1966).

Where Are You Now, My Son? by Joan Baez (Pickwick Records, 1973).

Joan’s vinyl album of poetry and singing against a backdrop of sounds recorded in Hanoi during the 1972 Christmas Bombings.