MY HOUSE IS MY HOME – IT’S THEIR HOME TOO, THOUGH, APPARENTLY

Today we live in snug, dry, comfortably furnished houses surrounded by the trappings of a well-earned civilised life. But we are not alone. Despite the power of modern technology, modern materials and highly toxic chemical poisons, we suffer a constant stream of unwanted visitors. Our houses, our food, our belongings and our very existence are under constant attack from a host of invaders eager to take advantage of our shelter, food stores and soft furnishings. Just as humans created nice comfortable, warm, homely places to live in, so too there are plenty of other creatures wanting to come in out of the cold.

Ever since humans took to living in shelters, wearing clothes, cooking food (along with storing supplies and dumping leftovers), tilling their fields and regimenting their gardens, they have played host to a wide and varied selection of ‘wild’ life. In evolutionary terms, humans have not been human for very long – probably for just a few hundred thousand years. So where did house sparrows and house mice live before there were houses? What did biscuit beetles eat before there were custard creams, Oreo cookies and fig rolls? What did clothes moths eat before there were designer jeans and hand-knitted cardies? Did the cigarette beetle breathe a little easier and live a healthier life before tobacco smoking took off? When the first carpets were laid, carpet beetles were waiting to take up residence in the deep pile, but where had they been living for the very many previous rug-free millennia? When the first caveman installed the first larder, it was soon infested with larder beetles; but which cupboards had they inhabited before the kitchen was invented? And long before the four-poster bed, where did bed bugs hide to sneak out for a night-time drink of blood?

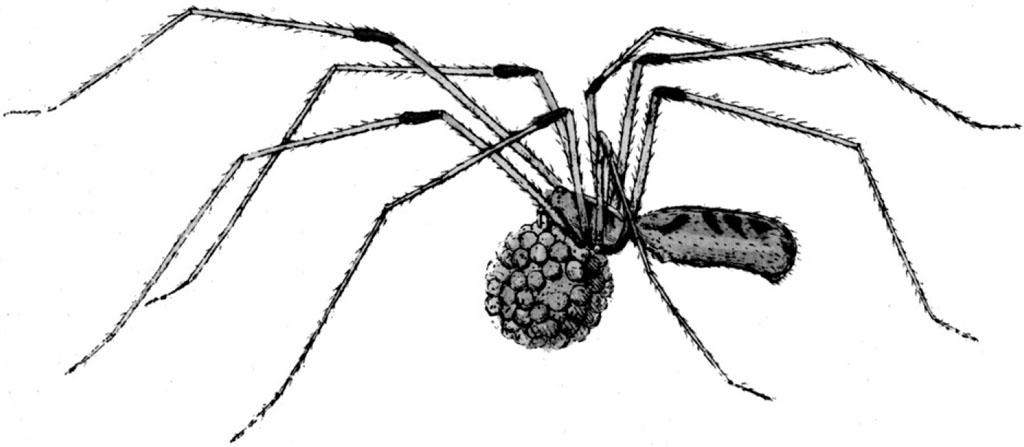

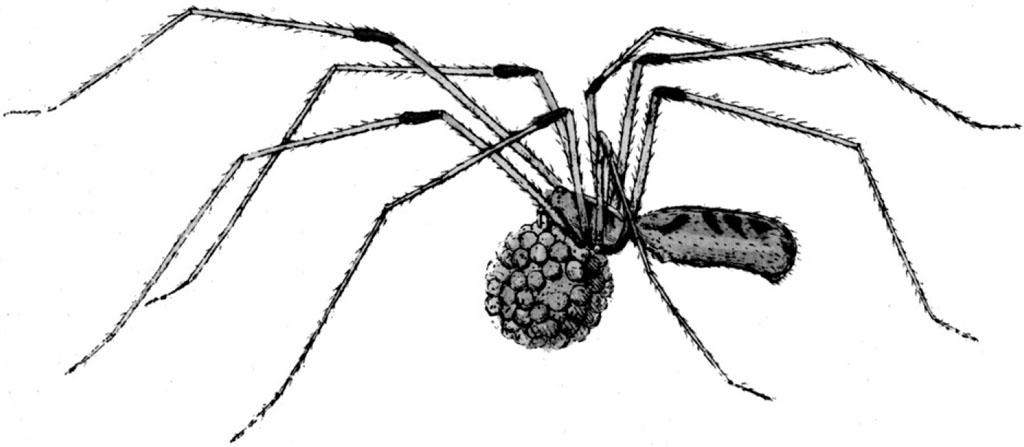

These are just some of the strange, charming and sometimes annoying creatures that have taken up residence with us. From bats in the belfry to beetles in the cellar, moths in the wardrobe and mosquitoes in the bedroom, humans cannot escape the attentions of wild nature. So where have all these creatures come from? Can we live with them? Or can we get rid of them? Should we get rid of them? Taking a quizzical look at all manner of household ‘visitors’, we can get a taste of human history (and prehistory), and an understanding of how we fit into the wider world, how we are part of the environment at large, how we are influencing it and how it has influenced us.

One of the first discoveries is that, although a random hoverfly might take a wrong turn and fly in through the open back door to bump on the insides of the window panes for a bit trying to get out again, most of the truly domestic creatures (those carpet beetles and bed bugs, but also grain beetles, house crickets and flour moths) are not simply wild animals sneakily crossing the threshold of the back door to steal a bit of food. Throughout most of the world these household animals do not occur ‘in the wild’ – they are no longer wild animals and they only occur in buildings occupied by humans. Somewhere, way back in our prehistory, we have picked up these inquisitive stragglers, and they have followed us around the globe, stowing away in our travel belongings, and being shipped across oceans and continents in trade cargoes. They are still travelling today.

This is not a pest-control handbook; it does not label our visitors, trespassers and intruders as good or bad, helpful or harmful; it has no recipes for spray poisons or repellents, or lists of extermination companies. Instead it considers the biology and ecology of these interlopers, and why millions of years of evolution have led them into the bathroom or the parlour, rather than into the forest or the field. It does, however, have an identification guide, so you can get an idea of what, exactly, you are dealing with.

Once you have identified your guests, you must decide whether you need to worry about what they will do to you, your belongings or your home. Some you will want to sweep out of the door as quickly as possible, or have removed by someone else with heavy-duty spraying or fumigating equipment; others you can afford to take a more cool and collected interest in. One person’s irritating larder infestation is another’s amusing after-dinner anecdote.

Richard Jones

London, 2014