STORED SUPPLIES, IN THE WAREHOUSE, THE CELLAR, THE LARDER AND THE PANTRY

It always starts with a casual nose-around. When you’re eying up a new property, the first thing to observe is the neighbourhood. Is it your sort of place? Does it

feel safe? What are the other residents like? So it is, too, for the animals looking to move into your home. However, they may have slightly different criteria by which to judge a particular

home’s suitability. Of little importance to them is the number of bathrooms and bedrooms, the availability of off-street parking or the colour of the front door. They will find more

importance in the period details – the exact overhang of the eaves, the detailing of the air-bricks and the fit (or not) of the window casements.

Like it or not, older homes are more attractive to house guests than new ones, if only because there are more gaps to get in and out by, more nooks to

accumulate dust and detritus, and more forgotten corners missed during the last exterior decoration session. Modern homes, and certainly modern high-rise developments, are much more boxy on the

outside, sealed against the elements and uninviting as roosts. A rural thatched cottage, on the other hand, is virtually just an extension of the garden hedge; almost anything can get into it.

One of the first ways into any house is through the roof. This is because house builders still have a tendency to regard a roof as just a roughly fitting lid to keep off the rain. There is

usually a loft void, or attic, but this is rarely a living space and more usually disregarded as little more than an indoor shed area for dumping unwanted items in uncertain limbo storage for

months or years. Ventilation, either through gaps where roof meets wall, or by special vented roof-tiles, is usually important for stopping moisture accumulating, and for keeping things, yes, dry.

Lofts are, very much, an invitation to enter.

EAVES – JUST A ROCK OVERHANG BY ANY OTHER NAME

Every year the coming of spring in northern latitudes is heralded by the arrival of charismatic birds wheeling through the clear blue sky. Swifts Apus apus, swallows

Hirundo rustica and house martins Delichon urbica fly north from their overwintering grounds in subtropical savannahs and take up residence again under our eaves. All are familiar

species (iconic some might say), perching on telegraph wires, swooping high over house tops, and screaming low over fields or down streets in our towns. They are all very much at home around

humans, and have been for centuries, because we provide for them a basic necessity of their lives – places to nest.

Swifts and swallows come right in under the edge of a roof to find a rafter surface or jutting brick on which to make their shallow dish-nest constructions. They are also known to nest in gaps

in thatch, in wall holes and on the ledges inside large, old chimney stacks. Swifts catch bits of airborne grass and fluff, and glue them together with saliva to make a precarious, barely rimmed

platform for their eggs, but swallows go a stage further and incorporate gobs of mud from pond and stream edges to make a shallow saucer affair.

It is house martins, however, which are most familiar around buildings – a clue is in the ‘house’ part of their common name and the urbica part of their scientific

name. These gregarious birds make very obvious nests under roof edges, against corbels or at the top of the window masonry (they were sometimes called window swallows in old books). Theirs are the

distinctive mud-daub cups, looking like half-coconuts, wedged in tight against the wood or brickwork, with just a small semicircular hole for the chicks to peek out of, and for the parent birds to

feed them through. The fact that house martin nests are outside does mean that they are sometimes blamed for guano splashes down the walls or on paths beneath, but at least they are not indoors, in

the loft, messing the joist spaces with excrement, nest material and bits of food, not to mention old eggshells and the occasional dead hatchling. Swifts and swallows are often lauded for their aerobatic skills, while the poor old house martins are vilified for their toilet habits.

It is pretty obvious where all these birds came from, before humans had invented eaves, rafters or thatch. Quite a few bird textbooks also mention them nesting occasionally on cliff-faces and

rocky outcrops. The house martin’s closest cousin is the sand martin Riparia riparia. In a few very rare instances, sand martins have nested in drainpipes projecting from walls or in

holes in brickwork, but they are really so-called for their habit of nesting in horizontal burrows dug into the exposed vertical faces of sand pits, railway cuttings, riverbanks, gorges, canyons

and sea cliffs. It seems quite likely that humans have enjoyed the exhilarating sight of these spectacular birds ever since they too took to sheltering in the abris of the Dordogne or indeed

anywhere against rocky overhangs.

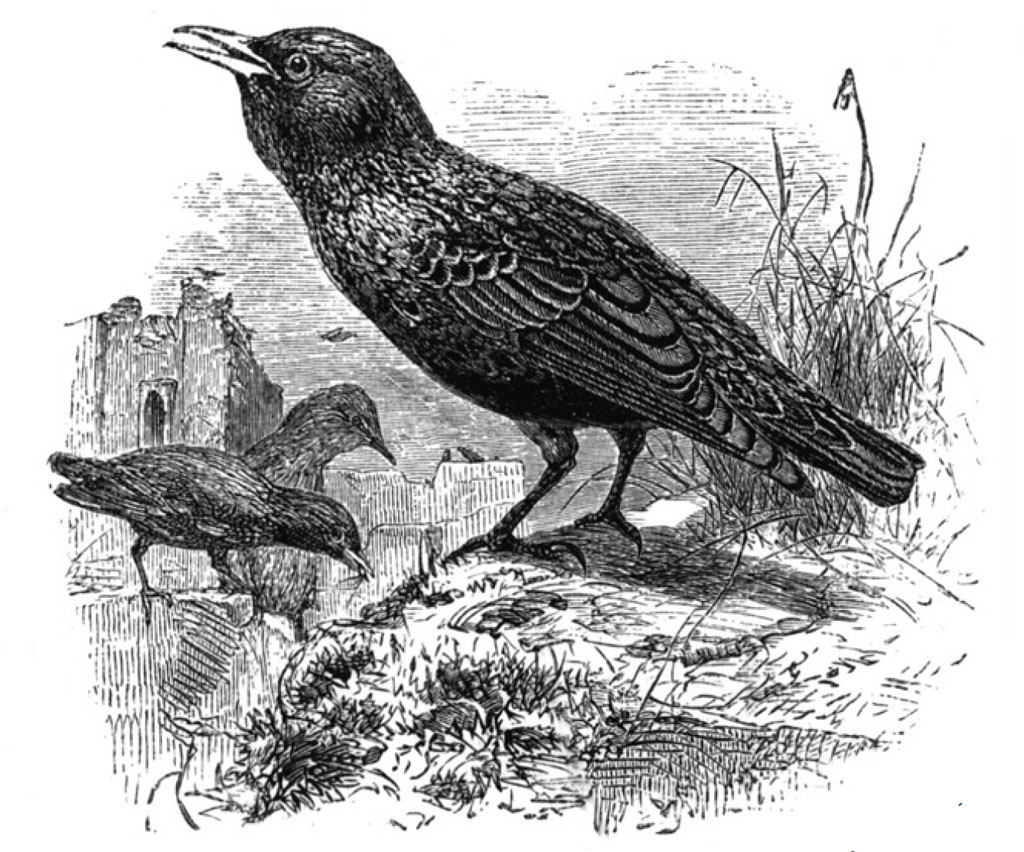

Eaves are also the easy way in for several other common ‘garden’ birds, including the starling Sturnus vulgaris and house sparrow Passer domesticus. The starling is

a citizen of the world, the Old World at least, and throughout Europe, Africa and Asia it is intimately associated with all man-made or man-influenced habitats, from garden and meadow, to reed bed

and coppice. Likewise, its nesting choices are varied, but it usually selects enclosed spaces, like a disused water spout, gutters, broken drainpipes, holes in walls (including disused dovecotes)

and spaces under eaves if it can find a gap in the roof. Away from human habitation it nests in whatever natural crevices it can find, including small hollows in rock-faces and tree-holes, which

are almost certainly the bird’s original ancestral breeding places.

No such easy observation is available for the house sparrow. Again, this cheeky bird is thoroughly habituated to humans, and occurs throughout Europe and Asia, but it is not immediately clear

what its lifestyle might have been before houses were available for it. It will nest in any hole in a building, or in creepers and climbers growing up the outside. It will

occasionally nest in a tall tree, but only a tree near buildings; occurrences of it nesting away from human dwellings or cultivation, such as high moors or deep forest, are virtually unknown. Here

it is replaced by the tree sparrow Passer montanus, although there is wide overlap of habitats. Tree sparrows are also common around rural villages and homesteads, and invade eaves and

thatch roofs, and the two species occasionally interbreed.

Genetic and morphometric studies on House Sparrow populations around the world (Felemban 1997) suggest that the species originated in the Middle East, where Arabian subspecies are larger and

more variable. Following a theme identified in many animals (Bergmann’s rule, after German biologist Carl Bergmann, who described the phenomenon in 1847), they grow larger at higher, cooler

altitudes and latitudes. This local variability is taken as a sign of a more diverse gene pool, and thus probably the origin of various colonisation ventures out across Europe and Asia. Here too

the birds nest away from buildings, in tree-holes and rock crevices, or lodge in the lower layers of the nests of larger birds like storks and crows. Received wisdom has it that both species of

sparrow started their human associations in this area with the birth of agriculture, and spread out with the increasing human dependence on grains.

Sparrows are omnivores, eating insects, worms, buds, fruits and seeds, but their appearance in crop fields and grain stores has brought them into fierce conflict with humans. This conflict can

reveal much about the balance that exists between humans and their domestic (or peridomestic) wildlife. Two conflicts in particular illustrate very interesting, but slightly different, aspects of

this human/wildlife interaction.

Between 1958 and 1962 the tree sparrow, identified as a major grain stealer, was one of the subjects of the Four Pests Campaign (the others being rats, mosquitoes and

flies), which the Chinese government sought to eradicate by mass public involvement. Birds were constantly scared off fields, shot and netted; their nests were pulled down and their eggs destroyed.

The population crashed, but rather than increasing grain yield the knock-on effect was that the insects on which the birds also fed now proliferated and locust plagues caused even greater shortage

and hardship. It turns out that although perhaps being a bit annoying, the sparrows were already part of an ecological balance that included humans and farming.

The house sparrow is now common and widespread in North America; however, this was not a natural colonisation, but the result of deliberate introductions. The first few pairs of birds were

released in Brooklyn, New York, during the 1850s. This was bolstered by further releases on the east and west coasts through to the 1870s (Barrows 1889). The reasons for the releases are variously

reported as being to control local insect pests, and out of nostalgia for Europe. The first birds did not thrive; they all died apparently. But such was the Victorian enthusiasm for acclimatising

‘good old’ species from the Old World to the New, that the releases continued and sparrows were soon spreading. They had found, just as larder beetles visiting the first larders had,

that they had been given a new niche to colonise, one well stocked with food, but pleasantly free of predators and parasites. In this case, however, it was not just the new habitat of human

buildings they discovered, but a completely new continent.

Today tree sparrows are all but extinct in China, and house sparrows have become nuisance ‘tramp sparrows’ in the USA and Canada. Ironically house sparrows are declining alarmingly

in Britain – a 70 per cent drop in numbers in the last 30 years is reported – making a once-familiar, commonplace garden bird into a species of some conservation importance and concern.

The reasons for the decline are unclear and may be to do with the decline of horse-drawn vehicles, dung in the streets and the insects attracted to it, the recent spate of loft conversions or

garden-insect pest control. While bird-conservation organisations monitor UK sparrow numbers and try to work out what is going on, sparrows’ decline does highlight, very poignantly, the nature of ‘pest’ status – how it can change suddenly, and that something should not be considered a pest unless it really reaches pest

proportions.

THE WELCOME DARK

A trip up into the loft usually involves fumbling in the dark for the inconveniently placed light switch attached to an off-centre joist support or, failing that, trying to find

a less than dim torch in a kitchen drawer. Darkness is often portrayed as dangerous, but to most creatures it offers a certain measure of safety, because if you can’t see, it stands to reason

that you can’t be seen – by predators. Lofts and attics are dark places, and this is why they are so attractive to many animals.

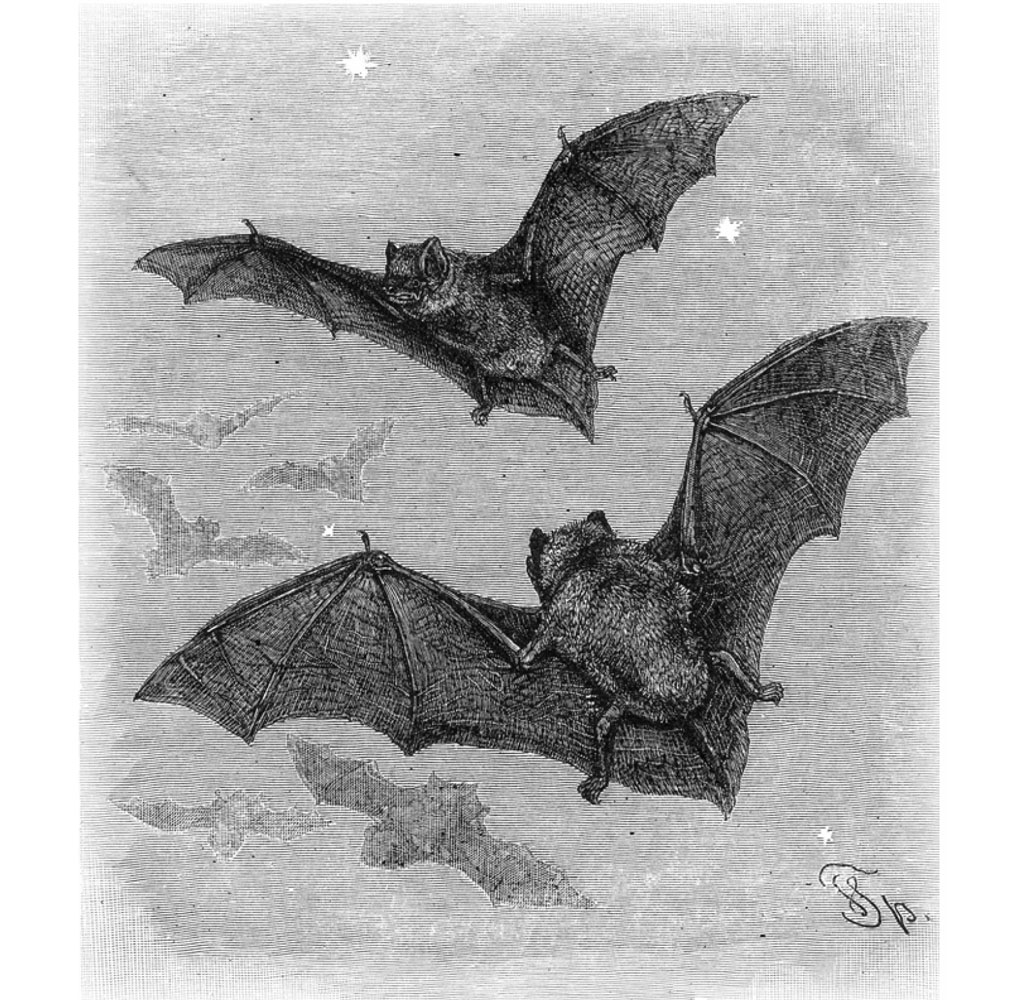

Bats, lords of the darkness by all accounts, used to be regular residents of loft spaces throughout the world. They still are in some rural areas, but in developing nations the towns and cities

are fast becoming less bat friendly – this despite bats being highly successful creatures.

With roughly 1,000 known species, bats are the second largest mammal group (after rodents). They are the only mammals to have evolved true flight. They have slow growth and long gestation, and

give birth to small litters, but they are long lived, with a lifespan of some 20 years; a similar-sized mouse has a lifespan of just one year. They owe their success to the dark. Darkness does not

necessarily coincide with the peak availability of food (mostly flying insects, though some bat species eat fruits), but it is the time to avoid birds. According to bat palaeontologists (Rydell and

Speakman 1995), the likelihood is that bats evolved flight first, by several million years, but then evolved nocturnality to avoid competition with and, more particularly, predation by much faster

flying birds.

During the day bats seek out safe dark places to roost. Apart from the obvious hollow trees and caves, loft spaces are second to none, although roosting in them does have the disadvantage of

bringing bats into close proximity with their greatest enemies – people. Bats don’t do much real harm; there might be a splatter of bat urine in the loft, and a

scatter of small faecal pellets on the patio beneath the small hole in the roof where they go in and out. Technically there is a risk of catching rabies from the bite of an infected bat, but only

where the disease is endemic, and only if you can first catch and then pick up a bat. It’s the human perception of bats that causes the greatest harm – to bats.

Bats’ sinister nocturnal habits, their rapid and seemingly erratic flapping motion, complete with investigatory swoops, and the rather vague misunderstood myths about vampires do nothing

to endear bats to us. Added to this, bats are now sufficiently scarce in some countries to merit significant nature-conservation value. In Britain, for example, it is illegal to kill, injure,

disturb or even handle a bat unless you have a special licence issued by the requisite government authority. This makes bats supremely inconvenient if they are roosting in the loft that a

householder wants to convert to an extra bedroom. There is a real cost implication, in terms of time waiting for roosts to become empty, or expert surveying and monitoring, if bats are discovered

in a roof space. This is just another reason why these guests are so unwelcome in the home.

Despite protection, bat numbers have been steeply declining for many years, and it is because their winter rather than their daytime roosts are being mucked about with. Since bats hibernate, a

true immobile torpor when the body temperature drops, the heartbeat slackens and the metabolic rate physiologically slows down, their winter quarters (as opposed to their daytime roosts) need to

offer long-term shelter over several months. Increasing numbers of loft conversions and roof-insulation schemes, compounded by almost universal central heating in homes, cause constant disruption

and displacement of bats at their most vulnerable time of the year. Although bats do not create nests, drop bedding or food, or damage household materials, their presence in

lofts is sometimes regarded with suspicion.

Bats can find their own way into the darkness of a loft by actively seeking out entry holes, which they detect by sight and echolocation. Cluster flies Pollenia rudis and other species

cluster as a result of the thermal qualities of walls and roofing tiles. These attractive, mottled grey, greenish or bluish, medium-sized flies are parasitoids of earthworms, so they are common

wherever there is soil, and they thrive in gardens. In late autumn, like many insects, they have a tendency to bask in the slanting rays of the sun, and often choose sunlit south-facing walls and

fences on which to warm up enough to fly. As the season progresses, their warming is not quite enough to get them airborne, so their physiological instinct is to hibernate; they begin to crawl

upwards away from the cold, damp soil to find a dry nook in which to overwinter. In their ancestral habitat this would have led them up into a tree-hole or crevice in a bank or rock-face. Now it

leads them up the wall or roof, to the small air gaps under the eaves or between the tiles and, true to their name, they cluster together in hibernation immobility.

Knots of cluster flies gather in corners against joists and rafters, and in favourable circumstances drifts of many hundreds or thousands can accumulate. Mostly these clusters go unnoticed, but

during the revival of spring the flies can become disorientated. Instead of exiting by the same gaps that they came in by, they find their way down into the living quarters of a building, much to

the consternation of the householder, who now finds hordes of stumbling or dead flies littering the window sills and floors.

An alternative effect of domestic roof design encourages another fly, the yellow swarming fly Thaumatomyia notata, to cluster in similar large groups. The larvae of these very small (2–3mm) flies burrow into grass roots, where they feed on other small soil invertebrates, so they are supremely abundant everywhere. During autumn they fly rather

ineffectually, and as they get wafted about by the prevailing winds they become trapped in eddies underneath the eaves on the leeward sides of houses. As soon as they regain their footing they

scramble up into any available gap to hibernate, and similar mass carnage is revealed when they start emerging from hibernation the following spring.

The chances are that this type of domestic clustering often goes unnoticed, or unreported. It was only because he had a pet entomologist for a relative that my cousin Terry Smith knew someone to

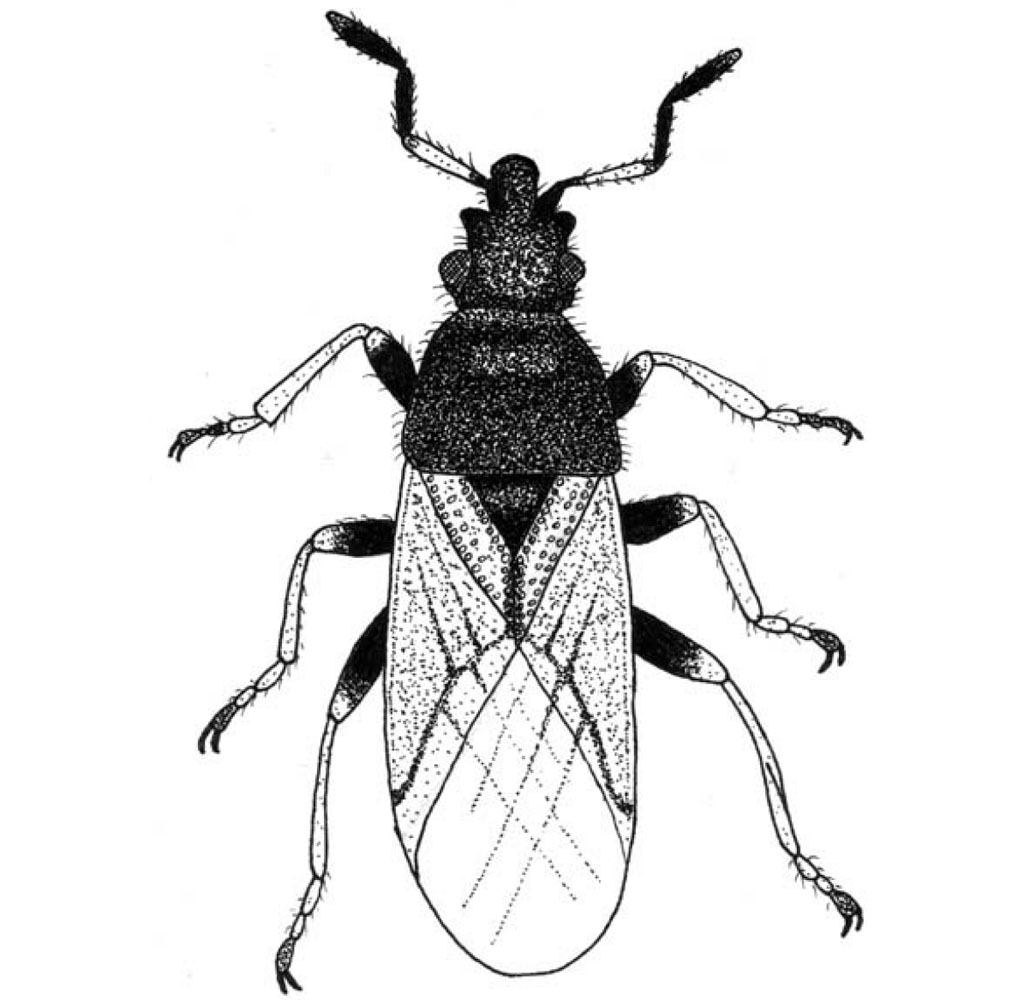

approach when he found vast swathes of small black-and-white bugs in the attic of his Kent home. Many hundreds were falling down dead around the house every day, and when they started dropping

through the loft-access hatch onto the bed at night, he was forced to seek professional advice. Instead, he approached me. The most unusual thing about this ‘infestation’ was that the

bug in question was a rather scarce species in Britain, without any common name but luxuriating in the scientific name Metopoplax ditomoides. It feeds on mayweeds and other wayside plants

on road verges, field edges, brownfield sites and wasteland in south-east England, and although it can be very abundant in some localities in this area, it has never been regarded as a domestic

pest. It’s difficult to make clear deductions from this one-off event, but it seems more than likely that the bugs (of a similar size to the yellow swarming fly) were being blown across from

the neighbouring fields and ended up under the eaves of the house.

Until the middle of the 20th century this little bug was known only from the Mediterranean region, but it has spread across northern Europe over the last 50 years (including

to the UK). Climate change has been invoked, but it will take many more years of study to test this assertion. It has also been transported to North America, probably in horticultural or

agricultural material, and has recently been found ‘swarming’ in houses in the USA and Canada (Lattin and Wetherill 2002). It won’t be long before a common name is coined for it.

Let’s hope it’s a little more imaginative than just ‘swarming bug’.

Flies and bugs are apt to get negative responses from householders, but few would take offence at butterflies. In temperate zones several butterfly species hibernate as adults; many also

overwinter at the egg, caterpillar or chrysalis stage, but it is as the adults that they can fly into buildings to find winter shelter. In the UK four butterflies are adult during winter. The

brimstone Gonepteryx rhamni is a delicately pale straw-yellow, and with gently sculpted wings looks like a dead leaf when at rest in a rose or bramble thicket. Three other butterflies, the

peacock Inachis io, small tortoiseshell Aglais urticae and comma Polygonia c-album, are brightly coloured above, but dark mottled grey and brown beneath. With the wings

clamped firmly closed, they are perfectly camouflaged hard up under the bases of large tree branches, inside hollow trunks or in the dim cool of small caves or shallow rock crevices, so much so

that finding them here in winter is a real triumph of naturalist skill and know-how. Less wilderness-tracker prowess is required to find them nestling down for a winter among the curtain folds of a

spare room, and sheds, too, are popular haunts. My sister finds small tortoiseshells in her wardrobe every year, shimmying down in a corner behind her wedding dress and party frocks.

The butterflies actually come indoors early, probably through open windows, long before real winter cold sets in, because hibernation is not just for deep winter; hiding is a good survival

technique, and getting under cover sooner also means having a much better chance of making it through to spring next year. Why court danger from predators by flying around

brazenly in autumn when the important biological acts of mating and egg laying will not happen for six months anyway?

Central heating sometimes arouses hibernating butterflies ahead of time, and they can be found listlessly fluttering inside a window in November or December. The best advice is to trap them

under a glass with a piece of card and let them go in a shed; they’ll soon cool down and settle down again, and wait to be got up at the right time, by natural sun warmth, in March or

April.

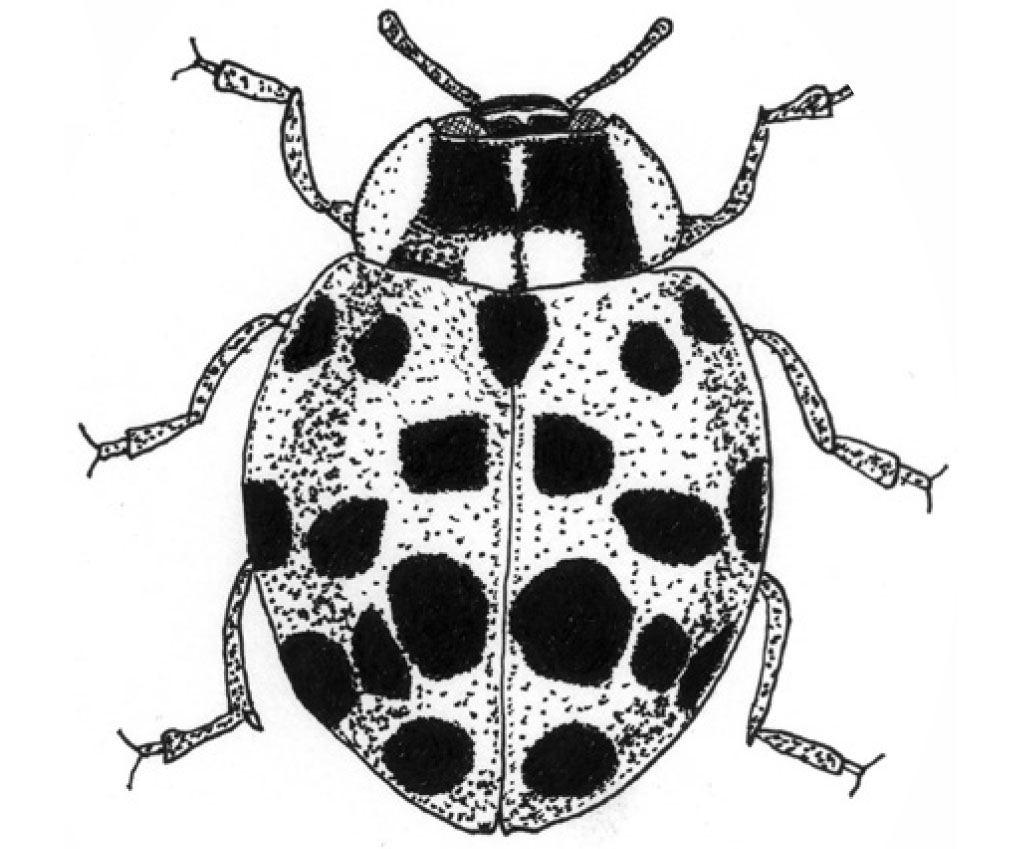

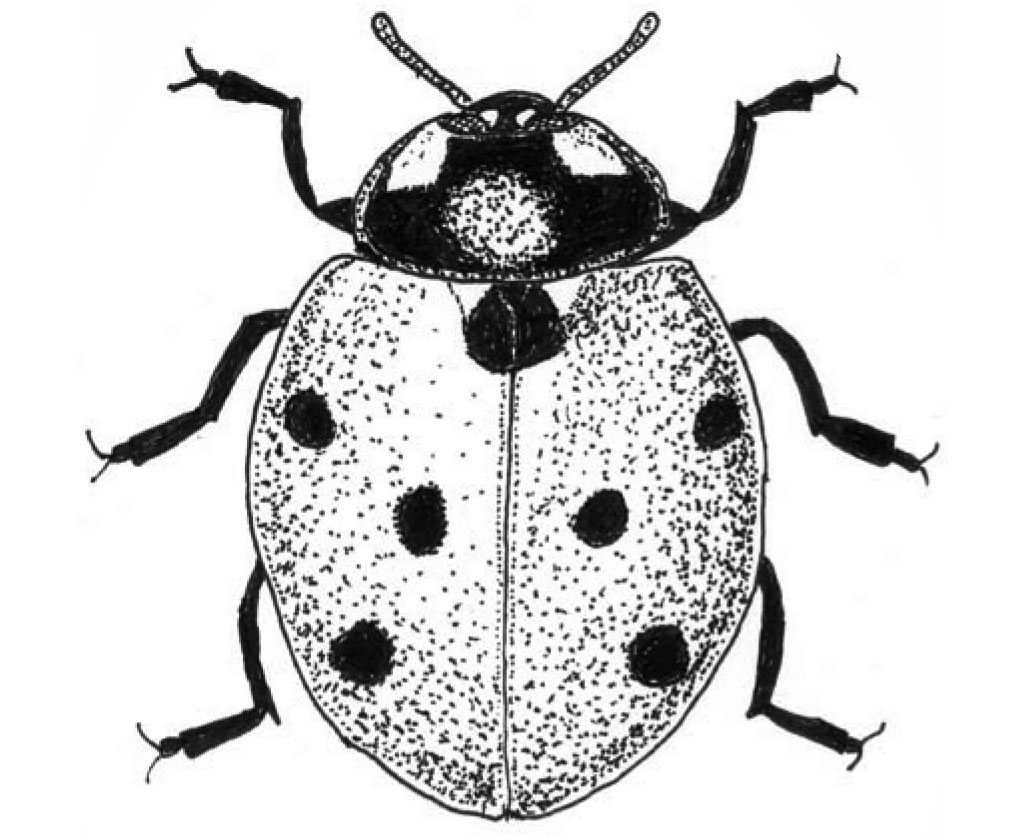

Ladybirds, too, were unlikely to cause upset if found indoors, but even these familiar and popular beetles are now starting to cause consternation – well, one species is. The harlequin

ladybird Harmonia axyridis is a native of China, Korea and Japan, but because of its large size and voracious appetite it has been captive bred, then deliberately transported around the

world and released as a biocontrol agent. It has been released to control large and hungry aphids, themselves often accidental alien imports, attacking field crops and orchards, and plants inside

glasshouses.

Initial reports suggested that this measure was working well. The adult ladybirds and their large, spiky larvae are ferocious predators of aphids and many other sap-sucking insects. The trouble

is that they also eat hoverfly larvae, lacewing larvae and the larvae of other ladybird species, all feeding in the aphid colonies. This has led to fears that the newcomers are out-competing and

actively destroying the original native wildlife. In the USA many native ladybirds have declined dramatically since the harlequin ladybird become widely established in the 1980s.

The harlequin ladybird was deliberately released in Europe at around the same time, but when it found its own way to Britain, in 2004, it was seen as a potential threat to the indigenous

ladybirds, and its inexorable spread has been monitored with awe and concern – it is currently all over England and is making its way into Wales, Scotland and Ireland (Roy et al.

2011).

One of the species’ most obvious habits is entering houses to hibernate. All ladybird species overwinter as adults, and they usually seek out a dry chink or cranny on

a tree trunk, plant stem or dead leaf in which to clamp down. Other useful hiding places include tree-holes, spaces under loose tree bark, small, rocky hollows and stony crevices. Several species

congregate in clumps, releasing a safety pheromone scent to recruit others to the growing knot. Ladybird warning colours, often black spots on red, but sometimes in other striking combinations of

black, red, yellow, orange and white, are a clear indication to would-be predators (mostly birds) that these beetles’ bodies are packed with bitter poisons and taste absolutely foul. Numerous

ladybirds huddling together emphasise this warning; throngs of many hundreds are recorded – and many millions in one US species. After they disperse the following spring some of the safety

scent remains, and although the original creators will have all died off by the next winter, a new generation is attracted to the same hollows and crevices. This continues year after year, in

response to the species-specific molecules lingering in the sheltered hidey-holes.

Having a few ladybirds tucked up into the edge of the window frame might be considered a quaint curiosity, but harlequin ladybirds appear in scores, waddling across ceilings and flying around at

head height in a sometimes alarming manner. Fears over biodiversity loss caused by them may offend entomologists, but fears of domestic invasion, even by a pretty ladybird, rank high among many

house dwellers where harlequin ladybirds have started to appear.

Perhaps the most unusual complaints about the harlequin ladybird have been made by North American wine makers (Pickering et al. 2004). The problems started when congregating ladybirds

were brought into the wineries while sheltering on the grapes, but wine manufacturers are also concerned about the insect’s habit of venturing into buildings during

winter, in particular into the large warehouses where wineries are operated. Once inside the large buildings the ladybirds nestle together in whatever sheltered corner they can find, including on

or in the fermentation vats. It does not take many of the large harlequin ladybird bodies to noticeably taint the wine with their acrid predator-defence chemicals.

CAVITY WALLS – THEREIN LIES DANGER

Loft spaces and spare rooms are at least accessible, and even infrequent visits provide a chance to have a look around to notice potential problems from invading plant bugs or cluster flies.

Cavity walls, however, are inaccessible and seldom noticed ... unless squatters take up residence.

Cavity walls, two skins of brick, stone or timber, with an insulating or moisture-preventing void between them, became part of standard building practice from the 1920s, but even older buildings

had the necessary air-bricks for underfloor and between-floor ventilation. Air-brick gratings are the perfect size to keep out birds and mice, but exactly correct to allow bees and wasps

through.

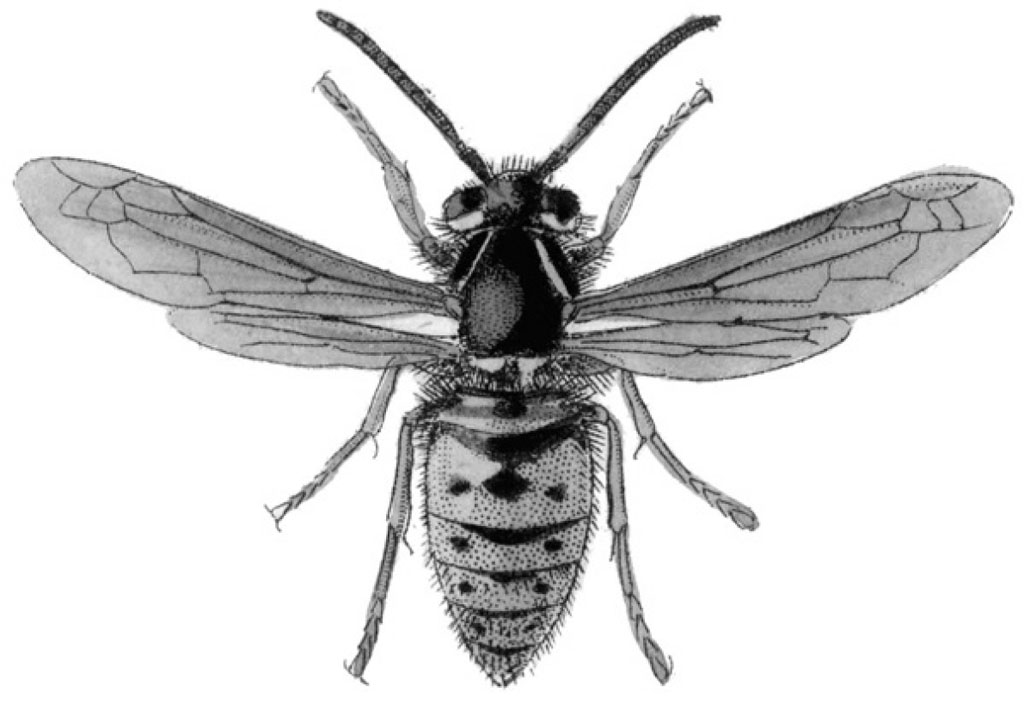

Social wasps (or yellowjackets), Vespula and Dolichovespula species, are familiar but much-maligned insects. Having a sting gives them an air of menace, and living in a colony

numbering anything up to 10,000 strong can make them seem intimidating. However, these regular lodgers in houses are quite likely to go unnoticed until the floorboards are taken up for maintenance,

or deep corners of the loft space are explored during roofing work. Even then, it is usually the abandoned and empty nests that are revealed.

A wasps’ nest is started by a single queen, working alone to make a tiny embryo nest the size of a golf ball. She constructs it out of paper chewed from logs and fences, and mulched with

saliva to make a paste smeared on and shaped with her jaws. A small, globular roof and 15–20 hexagonal cells is all it takes to get going. She lays the first eggs and forages for food,

insects caught on the wing and chewed to a gloop that is fed to the grubs. When the first batch of grubs is mature and hatched out, it forms the first cohort of workers

(sterile females), which take over food collection, paper manufacture and nest expansion. By midsummer 8,000 workers may have created a city the size of a beachball, with 6–10 large,

horizontal combs each with hundreds of hexagonal cells. The queen is more or less confined to egg laying.

Eventually, at the end of the season, new queens and males are produced. They leave the nest to mate and now the whole thing starts to wind down. Eventually all the wasps die off, except the

newly mated queens, which hibernate under loose bark or in a hidden dry crevice somewhere (they occasionally do so in a fold of a curtain). The huge nest is never used again, but remains in place,

quietly mouldering, for many years, its only occupants a few dead wasps that failed to emerge properly from their cells, and a few scavenger beetles. (Remember these beetles – we’ll

come back to them a bit later.)

Most wasps’ nests are subterranean, created in a small hole in a bank or mossy overhang, or under the edge of a log, but then actively excavated into a large cavity as the colony enlarges.

Because they start with just a founding queen, they are easy to miss at the beginning of the season, so nests in lofts, floor spaces and cavity walls go unnoticed until there is a veritable throng

of wasps, with comings and goings every few seconds and sometimes an audible hum coming through a wall or ceiling.

By this time it is hardly worth worrying about. If nobody has been stung yet, the chances are that nobody will be, and the wasps will continue flying in and out, completely oblivious of the

human occupants of the house. Of course, each situation has to be judged on its own merits; some people are so ill at ease with the idea of a wasps’ nest anywhere in the house that they will

have it removed, no matter how out of the way it is, and despite the protestations of any neighbourhood entomologists going on about how good wasps are for gardens, eating nuisance caterpillars,

aphids, flies and the like. Unfortunately, much time, energy, fuss and money is spent on eradicating wasps’ nests that never posed any problems, and which, in a few

weeks, will be empty anyway (Edwards 1980).

Things are not quite so simple when it comes to honeybees. Ostensibly similar to wasps in having large nests and hordes of foraging sterile (and stinging) female workers, there are several key

differences between wasps and bees, which are especially important to householders whose houses have been invaded. Whereas wasps are carnivores, hunting insect prey (although visiting flowers

occasionally), bees are wholly herbivore, feeding on nectar and pollen. Wasp colonies can reach 15,000 individuals, but honeybee nests can house 100,000 bees. Wasps make horizontal, one-sided combs

of hexagonal cells of paper, while bees make vertical hanging combs of back-to-back hexagonal cells from wax secreted from special glands on the undersides of their abdomens. Wasp cells are only

ever used for brood rearing, and contain the maggots until they are mature enough to pupate and emerge as new adults, but some honeybee combs are used to store honey; this is where it starts

getting interesting.

The western honeybee Apis mellifera is native to Asia, North-east Africa and the Middle East, and its honey stores brought it to the attention of foragers way back into human

prehistory. At first nests were raided and destroyed for the honey and wax, then bees were kept in hollow logs, clay pots, basket skeps and wooden hives, and their honey was harvested. Waring

(2011) and Preston (2006) both give good, readable histories of honeybee domestication and the insects’ interactions with humans down the ages. Now, honey is a multi-billion dollar industry,

and the bees have been transported far beyond their original natural range right across the globe to places where they never previously occurred – Europe, South Africa, Australasia and the

Americas. Today, the honeybee is thoroughly domesticated, in the developed world at least, and kept in man-made hives by back-yard beekeepers or industrial honey farmers. Any colonies found living

in natural hollows, such as ancient tree trunks and wall cavities, can only really be described as feral rather than truly wild.

Honey is not just a useful commodity for toast and cakes, adopted as the sweetener of choice by early humans; it is the honeybee’s secret of winter survival. Rather

than dying out, like wasps, at the end of the year, many thousands of honeybees huddle together in a tight hub at the centre of the combs, using their own metabolic body heat to keep each other

warm, and using the honey, a high-energy, pure-sugar solution, as food. The nest survives from one year to the next, and since new queens can be reared if the old queen dies (workers are constantly

replaced throughout the year), the colony is virtually immortal. It will only end if it is destroyed by disease, honey-hunting animals or humans.

Another major difference between wasps and bees is that new honeybee colonies are not created from scratch by a lone individual, but by a form of colony budding. When a large nest gets to a

certain size the workers start rearing extra queens, even if their own egg-laying matriarch is still going strong. When the new queens emerge they fight over succession, stinging each other to the

death until only one queen remains to take over the colony. Meanwhile the old queen takes off with a large cohort of the existing workers and they swarm – flying through the air in a great

cloud, before eventually settling to create a new nest somewhere else. Traditionally this was how beekeepers increased the number of their hives.

This does mean that if honeybees intend to establish a feral colony in a loft space or behind an air-brick grill, their presence is announced by the sudden immediate arrival of several thousand

bees. They are likely to be noticed very soon by the home owner. Occasionally they will find a hidden opening and create their new nest out of the way of suspicious eyes. As a boy, in the early

1970s, exploring the South Downs and Weald of Sussex, I was amazed to see an active bee colony high in the bell tower of St Andrew’s Church in Jevington, near Eastbourne. It was there for at

least a decade, presumably while the vicar and parishioners ignored it or overlooked it.

Honeybees have a good reputation (they are seen as busy, hardworking and industrious), compared with the unjust enmity heaped on wasps. But honeybees are the more dangerous insects to have

uncontrolled and away from the beekeeper’s eye. For a start they are more aggressive than wasps. If a wasp stings it hurts, but if you flick the insect off and move away

from the nest the other wasps will generally ignore you. If a honeybee stings its barbed stinger is prone to get stuck in the skin and ripped out from the insect’s body when it is brushed

off. The bee dies, but this seemingly suicidal act on her part leaves the muscular venom sac still squeezing the painful poison into the wound; her disembowelment also releases an airborne alarm

scent, which quickly alerts and agitates other bees to attack. If you are stung and the sting remains attached to you, you are now chemically tagged as the enemy, and the bees will pursue you much

more doggedly than will wasps.

On the whole bee stings are painful but not dangerous, unless they trigger an anaphylactic allergic reaction (which is thankfully very rare). The amount of toxin injected by a bee is minute

– 5–50µg (that’s micrograms, millionths of a gram), but ten bee stings can make even a healthy adult feel ill enough to need a cup of tea or take a lie-down;

50–100 stings and the victim should probably seek immediate medical help; 300 stings are likely to hospitalise the victim and are potentially fatal.

There are several honeybee races, bred over hundreds of years to produce more honey, to better survive in colder winters in northern climates, to cope with hotter, drier climates, or to be less

aggressive or more disease resistant. The most widespread race is the orange ‘Italian’ honeybee Apis mellifera ligustica, transported all around the world from the

Mediterranean, but the slightly darker Carnolian honeybee Apis mellifera carnica from Central Europe and the Balkans is more hardy, gentle and disease resistant. The traditional northern

European bee Apis mellifera mellifera is almost black and much more cold resistant than other races. It was probably introduced into Britain from Scandinavia, but was virtually wiped out

at the beginning of the 20th century by Isle of Wight disease, caused by a parasitic mite. It was soon replaced by importations of the other European strains (Jones 2011).

During the 1950s an African race, Apis mellifera scutellata, was examined because it was high yielding and highly pest and disease resistant. Unfortunately it was also much more

aggressive towards any perceived threat at the nest, and once the alarm scent was released by the first sting it triggered very large numbers of other workers to wage into the

assault – many thousands are recorded. Carefully quarantined laboratory experiments to cross it with more docile strains seemed to be working well until some ‘Africanised’

cross-bred bees were accidentally released in Brazil in 1957. They quickly established successful feral colonies and began to spread up through South then Central America, across Mexico and into

the USA. Today they occur from California to Florida, their aggressive behaviour earning them the unfortunate title ‘killer’ bees, since the multiple stings, delivering many times the

‘normal’ venom dose, make them much more dangerous than conventional hive bees, sometimes fatally so during their massed attacks.

Winston (1992) did much to put Africanisation into bee-history context, and tried to counter some of the needless fears exacerbated by dreadful film plots, but the bees continue to present a

domestic problem in Central America. Removing feral honeybee nests is now an important part of the work of pest-control operatives in the southern USA, and a house owner who finds honeybees

(Africanised or not) nesting in the fabric of his home would do well to have the nest removed as soon as possible.

FRIENDLY KILLERS ARE ALSO INVITED

Not all killers in the home are a danger to the human inhabitants. There is a time when visitors should be welcomed as guests and made to feel at home. A feature of some

traditional barns, now copied by conservationists, is the owl hole, an access gap high on the side of a barn, with a nesting platform provided inside. Unlike buzzards, kites and falcons, which have

been persecuted by landowners in the past because of perceived threats to game birds, owls have long been applauded for their control of mice and rats. Their friendly representation in

children’s literature from Edward Lear poems to Winnie the Pooh and Harry Potter has emphasised their benign nature.

Having some predators inside the living area, however, is still a difficult concept for many people, who seem unwilling to share their sacred space with things as creepy or ugly as scorpions,

centipedes or spiders. In most of the world the small scorpions that sometimes venture indoors are barely big enough to give a sting like a wasp, but some caution should be

exercised if, for the sake of family peace and calm, eviction is the only acceptable option.

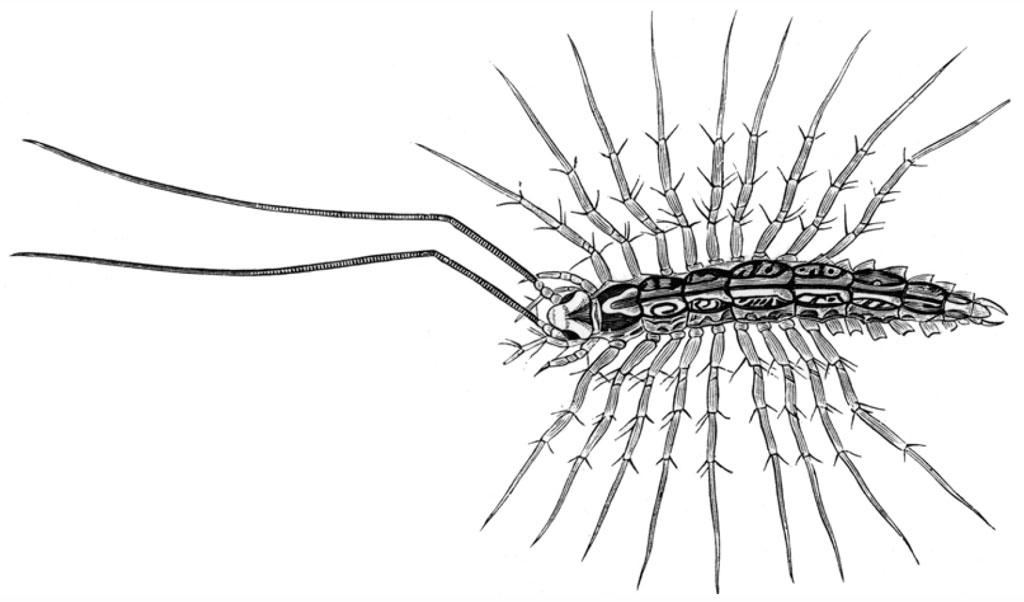

The large (10cm or more), stout centipedes of warm climates are best avoided as they can give a very painful bite if picked up. Centipedes’ front legs are modified into powerful biting

fangs, which are hollow and through which venom is injected to subdue their prey. These large species can easily pierce human skin, but the most familiar, the well-named house centipedes

Scutigera coleoptrata (and S. forceps in North America), are completely harmless. Their long legs, rippling in undulating synchrony and rapid turns of speed across wall or

ceiling, can make them a little startling, but their jaws are just not big enough to get a grip on a human finger or get through tough human skin. They will, however, make short work of mosquitoes

during their mainly nocturnal rambles – now that’s a consideration worth dwelling on.

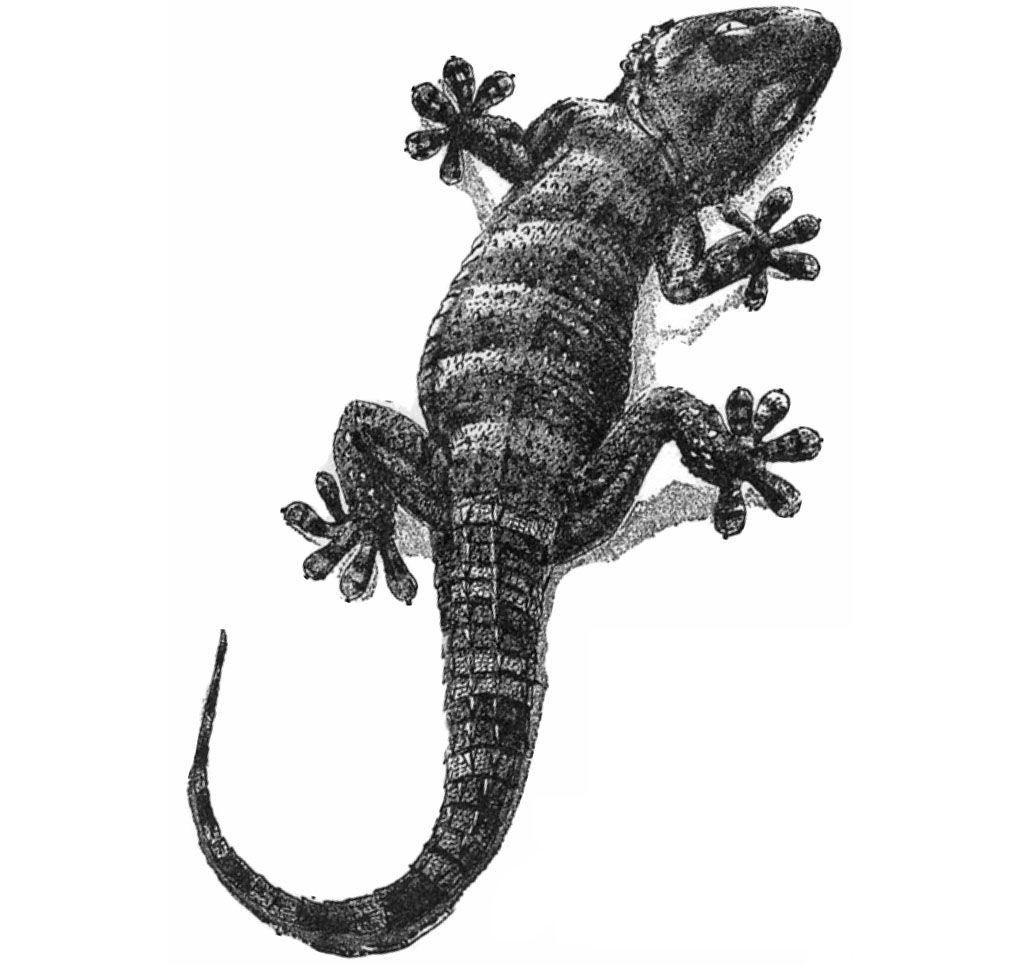

A similar plea might be made for geckos, the large-toed, ceiling-gripping tropical lizards. With their bright colours and large eyes, they are decidedly attractive and almost cute. I was quite

happy about the small brown gecko living in the wardrobe during my visit to Costa Rica, and in Sri Lanka the night-time squabbling of either mating or territorial pairs in the hotel colonnade

veranda at Anuradhapura was an entertaining diversion during an evening. But when I carried a large, bright green and turquoise, bug-eyed specimen in my cupped hands from the

conservatory of a Queensland restaurant back to the table, I wasn’t quite sure what all the fuss from my fellow diners was about.

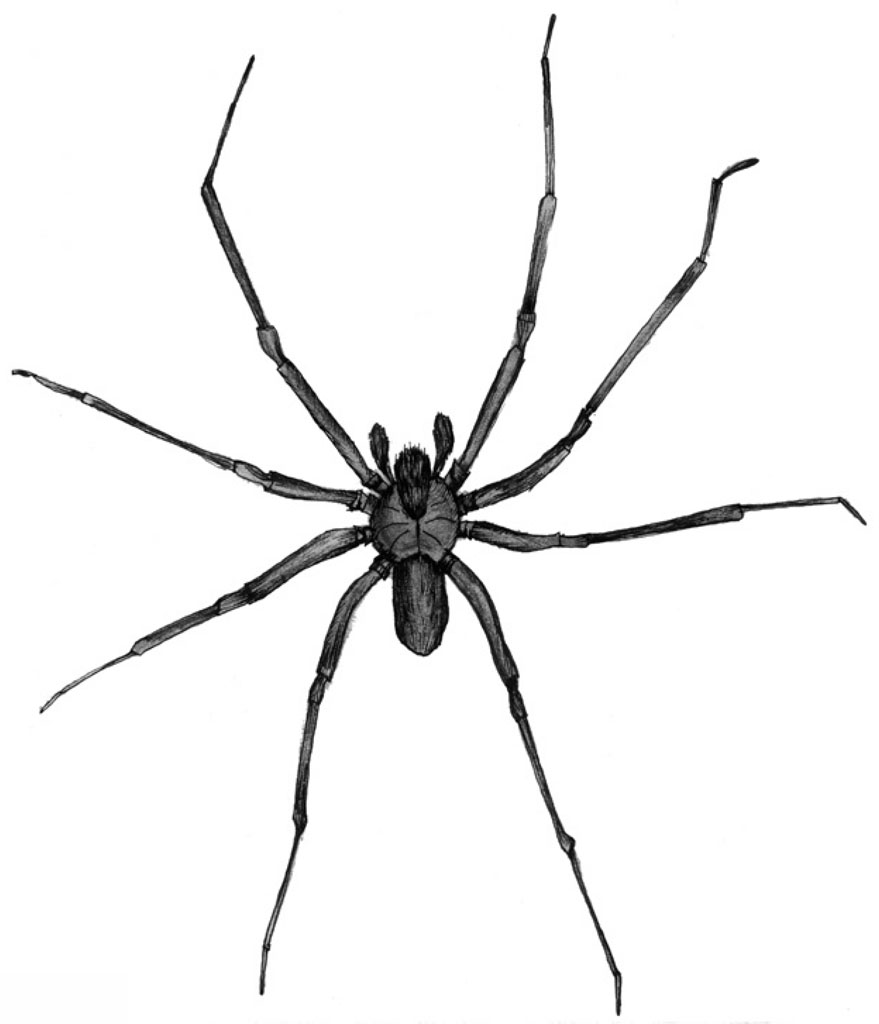

I am slightly more circumspect when it comes to mentioning spiders. There is no getting over the fact that many people just do not like them, no matter how good they are at catching house flies,

mosquitoes, beetle larvae, cockroaches and woodlice. The almost primordial fear of these delicate and attractive arachnids among humans causes much unnecessary angst. Luckily household spiders are

mostly secretive corner or crevice dwellers, and if they ever come out to hunt they do so at night.

Out of doors the stereotypical spider spins a large, round, carefully engineered web between plant stalks to catch flies. No orb-web spiders regularly come into the house. The indoor webs, if

ever found, are untidy messes. The daddy-long-legs spider Pholcus phalangioides lives up in deep corners of the ceiling, and makes a gantry of sparse silk strands hardly worthy of being

called a web at all. Here it sits motionless, sometimes for weeks, waiting for a disorientated fly to stumble into its trap. Sitting and waiting in a high corner is a useful quality, and one that

evolved in the spider’s original non-human habitat – caves, rock cavities and hollow tree trunks. Flying insects wafted into the darkness, or emerging into it after hibernation or

roost, have a tendency to fly upwards. The spider knows this, and waits.

Meanwhile, on the floor of the cave or stony hollow, or under a log or rock, house spiders Tegenaria domestica (and several other species) made their tatty handkerchief webs long before

there were houses. Hiding under the pale silk sheet, a house spider waits in a tunnel-like retreat with its feet resting on the web, and at the first feel of vibrations, as a beetle or bug crawls

over it, she rushes out and pounces with deadly intent. Nowadays the webbing sheets are mostly made behind furniture, underneath kitchen cabinets and under floorboards, where

they are seldom seen. What is seen, however, are the wandering males which, at a certain time in their lives, go off looking for mates. It is these that are seen wandering across the carpet in

front of the telly, or getting stuck in the bath when they fall in and are unable to scale the slippery sides to get out.

The very largest Tegenaria house spiders, reaching a body length of up to 20mm and a leg span of 100mm, may just be big enough to deliver a slight nip if picked up injudiciously between

the forefinger and thumb. However, body size and jaw size are not precisely calibrated among spiders, so those most famous for biting people are rarely overly large. Most infamous are species like

the black widow (Latrodectus mactans, nearly worldwide), funnel-web spiders (Atrax spp., Australia) and brown recluse spiders (Loxosceles spp., North and South America),

the bites of which can be extremely painful, and cause swelling, ulceration and occasionally even death. Any textbook of medical entomology will give full gruesome details of

spider bites and the biting perpetrators (for example Smith 1973).

Danger from spiders, however, is greatly overrated, and this is not helped by highly inaccurate identification by victims eager to blame any small scratch, infection, swelling or ill feeling on

a creepy-crawly they happen to see somewhere near at the time. Most spider-bite claims presented to medics do not have a captured spider as evidence, and in rare instances when the aggressor has

been caught the chances are that it will be a harmless species that got a lucky nip in a sensitive area of skin.

As it turns out, whatever their size all spiders are venomous. After all, this is how they catch their prey – by pranging it with their sharp, hollow fangs and injecting deadly

venom. But spider jaws are mostly very small, human skin is mostly very tough, and these disparaged arachnids are mostly physically incapable of getting their mouths open wide enough, or inserting

their short fangs far enough, to get any sort of purchase to properly bite a person.

Media headlines about spider bites are depressingly predictable; they are all about lurid sensational headlines and panic-mongering text, contain little or no scientific facts, and frequently

verge on the rabid. The ‘discovery’ by tabloid journalists that some small, pretty spiders very distantly related to the black widow could actually puncture human skin to deliver a

slightly painful sting, that these spiders could sometimes be found indoors and that they were apparently extending their range across Britain, maybe because of climate change, led to

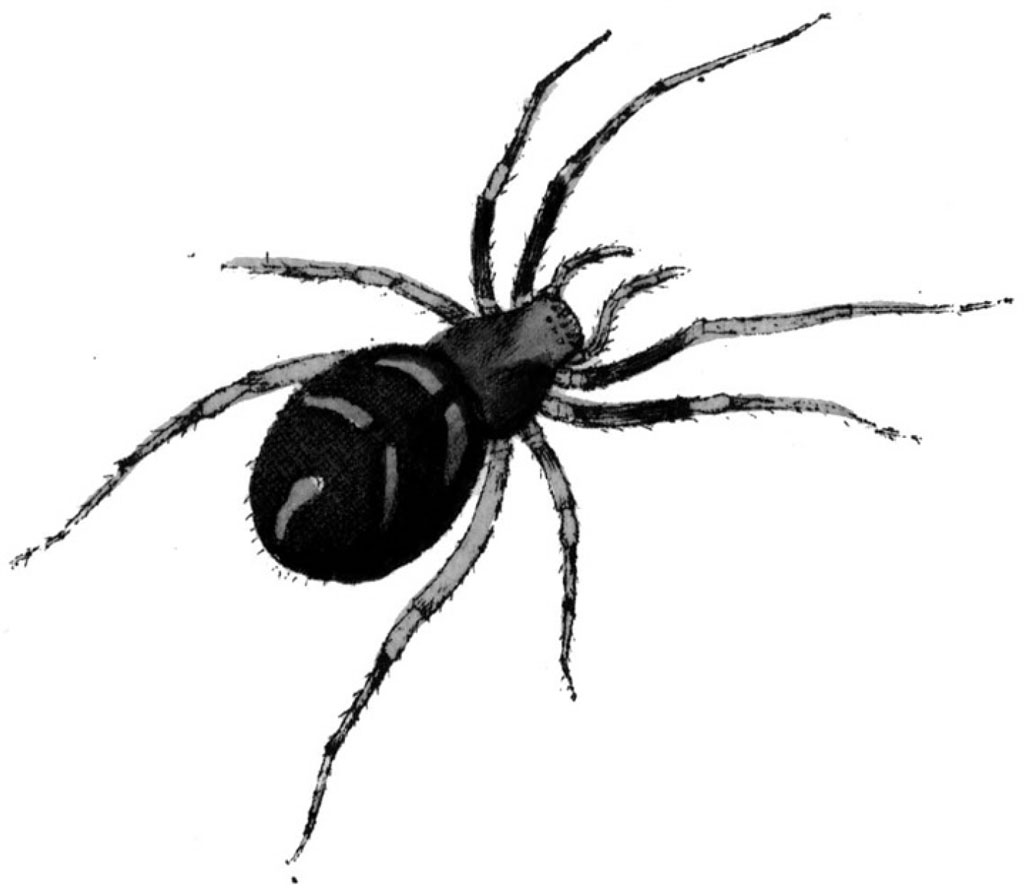

arachnohysteria on an unprecedented scale during 2013. Suddenly false widow spiders Steatoda nobilis and S. grossa were the new scourge of Christendom, and pictures of them

burgeoned on the Internet as frantic householders were desperate to seek reassurance that the spider they’d seen walking across the kitchen floor was not this dangerous beast.

Unfortunately for them it usually was one of these distinctive spiders that they saw, because they are very common and becoming more widespread in Britain. Both

species have long been known to occur in sheds and compost bins, garages and porches, and to come indoors occasionally. The name false widow still contains the accusing word ‘widow’,

with its deadly connotations, which is a shame because these spiders are much more true to an alternative English name – rabbit hutch spider (guinea-pig hutch spider in my case). This seems

an unlikely name to catch on among tabloid journalists, who prefer to emphasise danger in their stories. As I write this in December 2013, the brouhaha appears to be dying down. Perhaps this is

because, as one mockingly spoof website correctly put it, ‘The number of fatalities is currently hovering near the zero mark’.

There is a time to get annoyed, even aggressively so, with some household invaders, but this anger is wasted on spiders, and is ultimately counter-productive – they are actively helping us

to get rid of true life-threatening pests. The real danger from invaders is not from their invasion per se, but from the diseases they might bring with them.