1

HISTORICAL SOURCES

The cult of the phallus, the source of life and a symbol of virility, courage, and power, first appeared in the vast civilization that developed from India to the extreme edge of western Europe at the beginning of the Neolithic era following the end of the Ice Age about 8000 B.C. Closely tied to the bull and serpent cults, it has survived in India, with its rites and legends intact, to the present time, but its traces, symbols, and certain other cult elements can be discerned throughout not only all the civilizations of Mesopotamia, the Middle East, Egypt, and the Aegean but also those of Thrace, Italy, and the entire pre-Celtic world, including Ireland.

It is difficult to determine whether even more ancient sources existed in the immense history of humanity before the coming of our ancestor Cro-Magnon Man, which is to say before the debut of our own civilization, which thoroughly remains under its influence. The red horns that Italian drivers attach to the fronts of their trucks to avert misfortune, even today, are analogous to those used more than six thousand years ago by chariot drivers.

Among the cave paintings and carvings of the Paleolithic era, ritual representations of the feminine principle are especially noticeable. The man with the head of a bird and erect phallus of Lascaux (circa 20,000 B.C.) seems to be the exception. From the beginning of the Neolithic era, on the other hand, there are countless representations of the phallus and of ithyphallic figures, such as those of Altamira, Gourdan. and Isturits.

Jacques Dupuis has suggested in his latest book, Au Nom du Père, that this passage from worship of the vulva to that of the phallus could be linked to the discovery of paternity—something that is not evident in primitive civilizations.

"Since the phallus offers a kinesthetic and visual comparison to the serpent and fish, we might expect some storied recognition of the comparison, as was noted by the Abbé Breuil. Since the phallus was involved in the ejection of semen and urine, we might expect some storied explanation of these processes, which could compare with the vulval connection to menstrual blood. None of these stories concerning masculine processes need involve the female, nor include a knowledge of insemination or fertilization. They could be part of a specialized masculine mythology, perhaps told at the initiation of boys or at a convocation of hunters or as part of the male shaman's repertory" (Alexander Marshack, The Roots of Civilization, pp. 330-32).

Beginning with the Magdalenian epoch (about 13,000 B.C. to about 6000 B.C) representations of the phallus multiplied. The site of Audoubert in the Pyrenees is covered with engraved phalluses. In Placard (old Magdalenian) a bone has been found on which a phallus was carved with a stream of liquid leaving the meatus. It is similar to those of successive epochs, such as the phallic baton of Bruniquel (Dordogne) or the double phallus of the Gorge d'Enfer.

From Eyzies (later Magdalenian) comes a carved bone depicting the head of a bear, with its mouth open, facing a phallus whose testicles resemble flowers. Myth and tradition associate the image of the phallus to fish, water, and serpents.

Moravia: Phallic amulet of Dolni Vestonice. Gravettian culture, 30,000 B.C.

A fish is carved on the Gorge d'Enfer phallus. In Placard the eyes of the fish have the form of testicles. In Bruniquel can be found one phallic fish after another, all very realistic, with waves representing water. In the grotto of the Trois Frères, in Ariège, there are representations of masked, horned ithyphallic men wearing beast skins, who are very likely shamans, wizards, or dancers.

India is the only region where the cult of the lingam—the phallus—as well as its rituals and legendary narratives has been perpetuated without interruption from prehistory to the present day. It is thanks to Indian documents, therefore, that we are able to understand the reasons justifying the existence of this cult, the philosophical conceptions that explain it, and the significance of the legends whose variants, as we will see, are to be found everywhere.

The cult of the ithyphallic god of the protohistorical civilization of India was unknown to the Aryan invaders who came out of the north about the third millennium previous to our own era. The phallus cult has no place in Vedic rituals. The god-phallus (Shisna-deva) is, however, mentioned in the Rig Veda (712.5, and 10.99.3) as well as in the Nirukta (4.29), but its worship is banned.

It is the same in the Greco-Roman world where phallic cults came from civilizations predating the arrival of the Achaeans. "A colossal rough image of the ithyphallic god Min [dates] from predynastic Egypt (circa 4500 B.C.)" (Rawson, Primitive Erotic Art, p. 14).

The conflict between the ancient cult of Shiva, the ithyphallic god of Nature, and the social religion of the Aryan or Semite invaders is illustrated in the stories of the Purānas, the "ancient chronicles" of Shaivism.

According to the Shiva Purāna (Rudra Samhitā, Satī Khānda, 1.22-23), the patriarch Daksha, who is preparing a Vedic sacrifice, is cursed by Nandi (Joyous), the bull, the animal kingdom's companion and personification of Shiva, whose symbol is the phallus. Nandi speaks of Daksha with disdain:

"This ignorant mortal hates the sole god who remains benevolent towards his detractors, and he refuses to recognize the truth. He concerns himself with naught but his domestic life and all the compromises which that entails. To satisfy his interests he practices interminable rituals with a mentality debased by Vedic prescriptions. He forgets the nature of the soul, as he is preoccupied with something totally different. The brutal Daksha, who thinks only of his women, will hencefurth have the head of a goat. May this stupid individual, swollen with the vanity he takes in his own knowledge, as well as all those who with him oppose the Great Archer Shiva, continue to dwell in their ignorant ritualism.

"May these enemies of 'He who soothes suffering,' whose spirit is troubled by the odor of the sacrifices and flowery phrases of the Vedas, continue to dwell in their illusions. May all these priests who think only of eating, who put no stake in knowledge save that which profits them, that practice abstinence and ceremonies only to earn a living, seeking naught but wealth and honors, end up as beggars."

The vedic sage Bhrigu, who presides at the sacrifice, replies:

"All those who practice the rites of Shiva and follow him are only heretics who oppose the true faith. They have renounced ritual purity. They dwell in error. Their hair is tangled, and they wear necklaces of bones. They coat themselves in ashes. They practice the initiation rites of Shiva in which intoxicating liquors are considered sacred beverages. Since they scorn the Vedas and the Brahmans, the supports of the social order, they are heretics. The Vedas are the sole path of virtue. Thus let them follow their god, the king of evil spirits."

Despite this antagonism, Shaivism and the lingam cult were incorporated little by little into the Vedic religion as well as into numerous philosophical texts and legendary tales related to it. However, the whole of the texts coming from pre-Aryan culture and banned by the invaders were translated into their language, Sanskrit, and published only after the revival of Shaivism, starting about the second century B.C.

The oldest images of the ithyphallic god and the phallus in India come from the civilization of Mohenjo Daro (two or three millennia before our time). The megalithic monuments found in India and Europe, however, are even older.

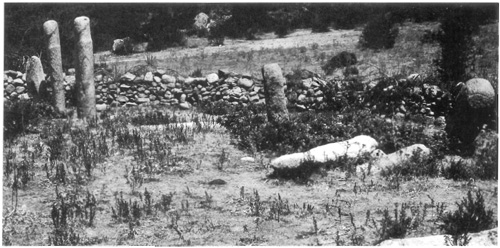

Corsica: Standing stones in phallic form, 3000 B.C. Photograph by Louis Trémellat.

Egypt: Glyph showing Pharaoh's power of procreation, Temple of Karnak exterior wall. Luxor. Photograph by Jeanie Levitan

The European megalithic complex precedes the Aegean contribution and the sexual significance of the menhirs is universally attested to.... the belief in the fertilizing virtues of the menhirs was still shared by European peasants at the beginning of the century. ... The megalithic complex would have radiated out from one sole center, very likely the eastern Mediterranean ... linked to Tantricism.... Stonehenge (before 2100 B.C.) is pre-Myceanean" (Mircea Eliade, Histoire des croyances et des idées religieuses, pp. 130 and 135).

We have discovered the worship of the phallus in both Mediterranean and northern Europe from prehistory to the Dionysian cults of the sixth century A.D. The phallus was worshiped in Egyptian temples. In Greece it played a large role in the ceremonies honoring Hermes and Dionysus. In Egypt special honors were given to the sex of the butchered Osiris. The worship of the sacred foreskin, brought back from Palestine by Godefroy of Bouillon and still practiced in France and Italy, is a vestige of this cult. One can see erect phalluses on tombs in Anatolia, in Phrygia from the pre-Hellenic epoch, and in Italy dating from the first Iron Age. In Rome, "the custom of sculpting a phallus on the walls of the city comes from the Etruscans" (Jean Mercadé, Roma Amor). This is also the case for the Roman bulla, a phallic amulet carried by Roman generals on the days commemorating their victories.

In the Greek world, Orpheus was originally considered a native of Thrace, where one phallus cult originated. Hermes was revered under the form of Priapus by a column crowned with a head and decorated with a sex organ.

"One of the most basic of Celtic god-types ... is the horned, phallic god of the Celtic tribes.... The earliest Celtic portrayal of the antlered god occurs in the ancient sanctuary in the Val Camonica in northern Italy ... round about 400 RC The antlered god is known from one inscription only as Cernunnos, 'The Horned One.' ... Over his left, bent arm are traces of the horned serpent, his most consistent cult animal. ... his worshipper, smaller in size and having his hands raised in the same orans posture as the god—a posture used by the Celts for prayer—is markedly ithyphallic.... Sometimes, in Roman contexts, the horned god was likened to Mercury, no doubt in his earlier role as the protector of the flocks and herds. Here too he is usually ithyphallic, but carries instead of weapons the purse and wand of the classical god" (Anne Ross, in Primitive Erotic Art, pp. 83-84).

Greece: Hermes of Siphnos. Marble. National Museum, Athens. Photograph by Antonia Mulas.