6

THE GUARDIAN GOD

HERMES

The phallus serves as protection against the evil eye, danger and misfortune.

"Every street corner in Athens had its cippus dedicated to Hermes, a square pilaster topped with the god's head and on which were sculpted genital organs in erection, which bypassers would touch for luck, because all luck is a gift from Hermes" (John Boardman and Eugenio La Rocca, Éros en Grecia, p. 40).

"In the countrysides there were columns erected at every crossroads to protect travelers from phantoms and unfortunate encounters. The Hermaic pillars were originally utilized as funerary symbols, but their multiplication along country, then city, roads, at crossroads, in town squares, and finally in houses is certainly due to the protective virtues they were assumed to possess. Like the rustic images of Priapus, they averted the evil eye, and popular piety attributed to them a beneficial power. While never reaching the importance of Dionysus in the Greek area, Hermes, in the form ofa pillar with genitalia, has largely profited from the cult of the phallus favored by the Dionsysian ritual" (Jean Mercadé, Eros Kalas, p. 89).

The name of Hermes derives from Hermaï—the cairn, or heap of stones, placed at roadsides, to which since prehistoric times has been attributed both a protective and a fertilizing presence. Transformed into columns and crowned with a head, the stones became the image of the god that bore their name (see p.10). The Apollo cult derived in equal measure from these stone piles, which were always distinctive signs of the sun god as well.

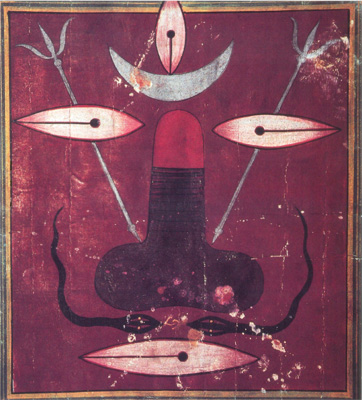

India: Tantric phallic painting Photograph by Lance Dane.

Legend places the birth of Hermes in a cavern on Mount Cyllene, and the product of the rape by Zeus of Maïa, the goddess Earth. His mother deposited him in a ritually consecrated willow basket. The master of animals, Hermes is the guardian of shepherds, flocks, and travelers delayed on the roads. He is cunning and deceitful, like Skanda, the son of Shiva, the god of thieves and looters. A treatise on the art of theft, the Sanmukha Kalpa, is attributed to Skanda. Barely out of the womb, Hermes stole Apollo's cattle. He stretched one of their hides on a tortoise shell and added a pair of horns, from which he then strung cords of gut, creating the first lyre. With the mysterious power of his music, he established the bond that ties together art and the mysteries. Presiding over the divinatory arts, he possessed a magic wand, the caduceus, and a cap that conferred invisibility upon its wearer. The equivalent of the Celtic Lug and the Egyptian Thot, he is the master of the initiate. He watches over the civilizing Hero, patron of the occult sciences, through the intermediary of the initiatory scenario, the sacrality of the sexual undertaking, vegetal fertility and nourishment. In the Eleusinian ritual, linked to an agrarian mysticism, the tray of offerings contained a phallus and a serpent or even cakes shaped like phalluses.

Hermes was also the inventor of fire, which was created by the friction of the male pestle in the feminine mortar. During spring sowing festivals, a large phallus representing Hermes was promenaded across the city, and orgiastic dances took place around the god's columns.

On the eve of the 415 B.C. expedition to Sicily, Alcibiades provoked the consternation of the city when he mutilated the Hermes columns in the public square of Athens in an act of defiance.

PRIAPUS

The name Priapus seems to be a derivative of the word briapnos (noisy) and would therefore be a translation of the Indian Rudra, the Howler.

Priapus, born as the result of an adventure between Dionysus and Aphrodite, was an ugly child possessing enormous genitals. He was reputedly a native of Lampsachus in Mysia. His cult spread to the Aegean islands and thence to Rome, where it blended into those of Pan and even more specifically into that cult of the ancient Etruscan phallic deity called Mutinus-Tutinus or Tutinus-Mutinus (from muto, the virile member).

As a gardening god, Priapus carries a pruning knife. He is responsible for the safeguarding of vineyards and orchards. He is represented under an ithyphallic form because that attribute deflects any evil spell that could cause harm to the crops. Very highly regarded by the people of Rome, he was represented there as Hermes, by a cippus topped with a head and adorned with an erect phallus.

The Priapus of Verona carries a basket full of phalluses, along with a serpent biting his penis.

In Rome the image of Priapus, painted with cinnabar or vermilion, was placed in entranceways fur protection. The phallus bestowed good luck while dispelling danger and driving away the furces seeking to do evil. It played an important role in initiation rites. "In Egypt as well as in the Greco-Roman world the powerful temples attributed to the phallus the power of paralyzing or dispelling dark and demonic forces" (Julius Evola, Le Yoga tantrique, p. 112). In Rome, according to Macrobus, a phallus of great size was suspended upon the chariots of victorious generals because of the maxim fortuna gloriae carnifex, success destroys luck. Only the presence of the Fascinus permitted one to confront this dreadful test of success.

Phallic amulets.

"The phallus possesses a magical power that is particularly effective against the evil eye.... This is why one finds so many phallic amulets and so many sex organs carved on the walls of houses, in Greek Delos, just as in Pompei" (John Boardman and Eugenio La Rocca, Éros en Grecia, p. 42).

"Those who steadfastly worship the Great God under the form of the phallus are freed from fear and the cycle of birth and death" (Linga Purāna, 2.6.40). In India, the image of the lingam and the representations of sexual couplings protect house and temple against lightning and other calamities.

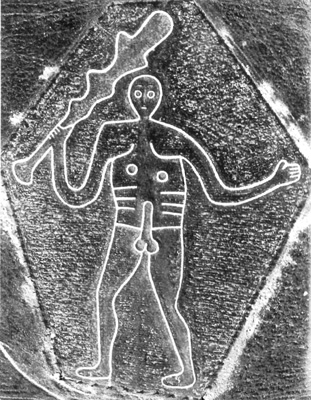

"Another type of early portrayal of the human figure, the sexual potency and fertility associations of which cannot be in question, is found widely in Europe.... In general, they consist of representations of emphatically phallic men engaged in some activity such as hunting, fighting, sorcery or ball-games.... Somewhat later in date, belonging perhaps to the early Romano-British period, is the famous chalk-cut figure on the hill above Cerne Abbas, Dorset. Known as the Cerne Abbas giant, this British 'Hercules' with his all-conquering club, like that of the great Irish god Dagda, and his huge penis and testicles, has survived through the centuries, dominating the surrounding countryside, defining the Church, and remaining down to the present day a powerful fertility symbol. Young couples about to be married still resort to him, and it was believed in the district that to have sexual intercourse within the hollow of the vast phallus could only have beneficial results" (Anne Ross, in Primitive Erotic Art, pp. 81–82)

British Isles: Drawing on the earth of Cerne Abbas Giant, circa first century B.C. Dorset.

"There are numerous references and hints in European literature to the fact that not only art-made objects but actual human genitals were felt to have a magical power, especially in averting all kinds of misfortunes" (Philip Rawson, Primitive Erotic Art, p. 76).

In the popular conception that still thrives today in the countries of the Mediterranean, men touch their sex to avert the evil eye and make the evocative gesture of the mano impudica to invoke luck. Realistic and symbolic emblems of the male sex organ have often been planted in their fields by agrarian peoples. In southern Italy, phallic markers serving as boundaries have survived into the present day. Some of these were stone blocks from which emerged a phallus, sometimes accompanied with a human head as well. They were called Priapus, Hermes, Liber, Tutinus, or Mutinus (Rawson, pp. 52 and 82).

The Shaivites wear a small phallus at their throats, as did the ancient Romans. Numerous examples of this can be seen at Pompeii. In India a stone lingam is worshiped in every household, and large wooden phalluses are carried in holy processions. Herodotus mentions the carrying of phallic emblems in the processions of Dionysus and Osiris. "The figures with disproportionately large phalluses that the Egyptians carried in procession during the festival of Osiris were stored in the Temple of Hieropolis, in Syria" (J.-A. Dulaure, Des Divinités génératrices et du culte du phallus, p. 82).

Nepal: Ek Mukh lingam of Shiva. Kathmandu. Photograph by Kellin Bubriski.

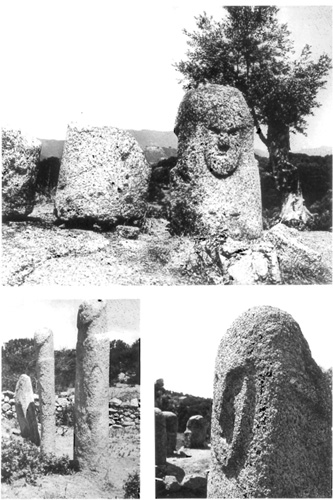

Corsica: Standing stones in phallic form, 3000 B.C. Photograph by Louis Trémellat.

The god Priapus ruled over the phallophorias of each and every god. Men and women alike participated in erotic songs and orgies. In the agrarian cycles of Athens, cakes were made in the forms of phalluses or of serpents, the pieces of which were blended in with seeds. In Rome, "an ass was sacrificed to Priapus and offerings of flowers, fruits, milk, and honey were made to him" (Dulaire, op. cit., p. 83).

"Until very recently phallic cakes were baked by German, French and Italian peasants at Easter to be carried in procession to the church." "At Trani, by Naples, a huge wooden phallic image called II Santo Membro was carried in procession annually until the eighteenth century" (Philip Rawson, Primitive Erotic Art pp. 53; 75).

"The habit of placing a phallus on the walls of buildings, a practice that came from the Romans, still existed in the Middle Ages, and the edifices most specifically placed under the influence of this symbol were churches, where they served as protection against all kinds of enchantment, in which the population of that time lived constantly in fear. They protected not only the place they adorned and those who frequented it, but also those who looked on it from afar with faith. They were usually placed at doorways, like that of the cathedral of Toulouse and several other churches in Bordeaux and elsewhere in France. But, during the Revolution, they were destroyed by an ignorant populace who saw in them a sign of the clergy's depravity" (Payne Knight, The Worship of Priapus, p. 114). A wooden phallus can still be seen today in the basilica of St. Bertrand of Comminges.

THE GOD OF THE HUMBLE

Shiva, god of the pre-Aryan peoples of India, remained their preferred deity, even after their enslavement and degradation to the stature of artisan castes in the world dominated by their invaders. The Hymn of the One Hundred Rudra of the Vājaseneya Samhitā (Yajur Veda, 16.1) invokes him as the patron of craftsmen, cart drivers, carpenters, blacksmiths, potters, hunters, water bearers, and woodsmen. He is the god of soldiers, mercenaries, and the intrepid chariot driver. Shiva is also the god of the vrātya, the ascetic beggars and wanderers (P. Banerjee, Early Indian Religions, p. 41 ).

India; Shiva as youth with elongated phallus. Photograph by Lance Dane.

India: Shiva lingam in worship in the shrine of Gananath. Photograph by Nik Douglas.

"In Shaivism, transcendence in relation to the norms of everyday life is translated on the popular plane by the fact that Shiva, among others, is represented as the god or "patron" of those who do not lead a normal life and even those who are outlaws" (Julius Evola, Le Yoga tantrique, p.91).

Shiva was the god of the humble; his teachings were addressed to all mankind. Brahmanic texts reproach him for having taught the lower classes the secrets of the myths, the rituals, and the highest levels of knowledge and for having opened the path of initiation to them. Phallic rites are essentially folk rites. The Shatapatha Brāhmana (5.3.2) mentions the shūdra, the artisans, as participants in sacrifices to Shiva and to soma, the sacred liquor absorbed as the sperm of the god. Even today, in the most important Shaivite shrines, the service is practiced alternately by Aryan brahman priests and shūdra worker-priests. A non-Aryan priesthood has therefore survived throughout the centuries, despite four thousand years of Aryan domination. "In the mahratta regions, where the Shaivites predominate, brahmans do not officiate in the temples. That function is reserved to a special caste, called gurava, which is of shūdra origin, not Aryan" (P. Banerjee, Early Indian Religion, p. 41). The traditions of these non-Aryan priests are poorly known in a Hindu world dominated by high castes that if not Aryan are totally Aryanized. No modern study concerning them exists.