9

THE SURVIVALS

"Antiquity made Priapus into a god; the Middle Ages made him into a saint, who, under several names, remains present throughout the Christian world. In the Midi of France and in Provence, Languedoc, and the Lyonnais region, Priapus continues to be worshiped under the name of Saint Foutin, to whom the Priapian attribute was transmitted under the form of a large wooden phallus. The cult of this saint, as it was practiced in the seventh century, is described by Pierre de L'Estoile in La Confession de Sancy (fifth volume of Henry Ill's Journal). We learn there that phalluses dedicated to Saint Foutin were suspended from the chapel ceilings. When the wind agitated them they produced a soft murmuring, which at times disturbed the serenity of devoted souls.

"In Embrun, in the High Alps, women poured libations of wine on the head of Saint Foutin's phallus. When the wine collected there turned to vinegar it was then employed for a use that is only obscurely alluded to. When the Protestants took Embrun in 1585, they found the phallus preserved among the relics of the church, the head still reddened from the ablutions of wine. Another phallus, covered with hide, was the object of a cult in the church of Saint Eutrope in Orange. The Protestants seized it and burned it publicly in 1562" (Payne Knight, The Worship of Priapus, p. 66).

France: Folk art of clergyman with member. Wood with secret compartment. Collection of Jacques Cloarec.

"Near Clermont, in Auvergne, an isolated rock can be found that has the shape of a large phallus and is called Saint Foutin. Analogous phallic saints were worshiped under the names of Saint Guerlichon or Greluchon, in the diocese of Bourges, Saint Gilles in the Cotentin, Saint Remy in Anjou, Saint Regnaud in Burgundy, Saint Arnaud and especially Saint Guignole near Brest, and in the village of La Chatelette in Bercy.

"Very many of these phalluses were still an object of worship in the eighteenth century. Certain among them were worn down by the continual rubbings employed upon them to obtain their powder" (Payne Knight, in The Worship of Generative Power, p. 133).

In Antwerp, Belgium, until relatively recently, Priapus was worshiped under the name of Ters (a word of unknown origin but identical in meaning with the Greek phallus or the Latin fascinum). Joannis Goropius, in his Origines Antwerpianae on the antiquities of Antwerp, in the middle of the sixteenth century, explains why the Ters was worshiped by the people of Antwerp: "When women drop an object, fall down, or if some unexpected accident frustrates them, even the most respectable invoke Priapus with loud cries under his obscene name to obtain his protection. On the door of the city prison can be found a statue that had been provided with a phallus that is now entirely worn away" (Joannis Goropi Becani, Origines Antwerpiae [1569], 1.26-101).

Abraham Golnitz, in his ltinerarium Belgico-Gallicum (1631) mentions a phallus at the entrance to the cloister of the church of Saint Walpurgis in Antwerp, which had been constructed on the site of an ancient temple dedicated to Priapus. The Antwerp citizens, at certain times of the year, decorated this phallus with flowers and came to scratch it to obtain the powder, which was used as a remedy against sterility.

In Montreux, near Carpentras, in a twelfth or thirteenth century church is a phallus of Saint Didier that is celebrated on the second Sunday in May. Moreover, in the same region and still worshiped even today is Saint Gens, within a grotto shaped like a vagina. Young men take the image of the saint and race with it several kilometers to the grotto. There they take water and mix it with their sperm, which they then try to induce the woman of their choice to drink. The emblem of Saint Gens is a plowshare pulled by a wolf and a cow.

France: Folk art of monk inserted inside a phallus. Terracotta.

India: Shiva personified on his linga. Bronze, late eighteenth century. Photograph by Lance Dane.

According to Daulaire, until relatively recently, in the village of Saintes on Palm Sunday, which was called the Festival of Penises, phallus-shaped biscuits were distributed.

Sir William Hamilton, an English resident of the Naples court, in a letter dated December 30, 1871, recounts that in Isernia, near Naples, for the festival of Saints Cosmas and Damien on September 27, a phallus that was prudishly called Saint Cosmas's big toe was displayed in the church. Wax phalluses were sold as good luck charms.

The rites of Priapus, used to combat livestock disease, continued in England until the thirteenth century.

"At the beginning of 1882, between March 29 and April 5, a priest of the parish of Inverkeithing, Scotland, celebrated the rites of Priapus by gathering the young women of the town together and making them dance around the god's statue. Parading a wooden image of the male organ of generation, he himself sang and danced while accompanying his song with gestures and attitudes adapted to the surrounding circumstances, and encouraged licentious acts from the participants with words that were no less so. The more timid of those in attendance, scandalized by these proceedings, reproached him, to which he responded in derision. Cited to appear before his archbishop, he excused himself, explaining that it was local custom, and he was granted leave to keep his post" (Chronicle of Lancercosted, p. 109).

The custom of carrying small phalluses as protection against bad luck and pernicious influences, widespread among the Romans, persisted throughout the Middle Ages and has never been completely abandoned. It has been a constant practice among the Gypsies. In Italy the phallus is sometimes replaced with a horn. In France, in a note on the decorated lead figures found in the Seine and collected by Arthur Forgeais (Paris, 1858) we learn that "almost all these phalluses have wings; one of them has bird feet and claws, and another has a sort of bell hanging at its neck. These objects are analogous to Roman phallic ornaments discovered in Pompeii. One is a representation of a woman astride a horse on top of a phallus with human legs; another has dog legs. One of them represents a little man with an enormous phallus.

"In San Agatha di Gaeti, near Naples, a gold-handled cross has been found composed of four phalluses. It has been constructed to be suspended and must have belonged to some powerful individual. In Italy these phallic amulets are in common use and are sold daily, in Naples, for one carlo each, which is the equivalent of four pence in English money or four French centimes. One of them, as can be seen, is entwined by a serpent. They are considered so effective in safeguarding the personal security of those who carry them that perhaps there isn't a Neapolitan peasant who doesn't make a habit of carrying one in his coat pocket.

The god Osiris taking the phallic oath. British Museum Illustration from Rufus Camphausen's Encyclopedia of Erotic Wisdom (Inner Traditions).

"There is yet another less evident emblem of the phallus, which has ruled as an amulet since time immemorial. Antique dealers have called it the phallic hand. The ancients had two forms of this hand, one in which the middle finger was extended while the thumb and other fingers were folded back, and the other in the form of a fist but with the thumb passing between the index and middle fingers. The first of these forms is the more ancient. The extension of the finger represents the extension of the membrum virile, and the fingers folded back on either side represent the testicles; this is why the Romans called the middle finger the digitus impudieus or infamis. To display one's hand in this form was considered the most contemptuous of insults, because it designated the person to whom it was addressed as one given to vices that went against nature. This was also the significance attributed to it by the Romans" (Payne Knight, in The Worship of Generative Power).

Vignette from an 1860 novel.

The Roman carnival inherited Priapus, whom it transformed into Pulcinella (Punch) of the stiff-bearded chin and pointed ears. The Italian ethnologist Annabella Rossi has published a study on the phallic and hermaphroditic character of Pulcinella, whose name comes from pollice (thumb). Like Attis and Mithra, he in fact wears the pileus, the pointed cap that is characteristic of the phallic cult mysteries. He is called eetrulo (Cucumber) in reference to the vegetable of phallic significance. He also holds a horn. His humpback, which brings good luck, is considered a sign of hermaphroditism.

"In Martano, in Lecce province, on Easter Sunday, people seeking a cure go to a chapel where a menhir is to be found and have to pass through a hole in the stone. Such healing, by sliding through a hole or through a narrow space between two stones, is a prehistoric rite that is to be found throughout the whole of Europe" (Alphonso di Nola, L'Areo di Rovo, p. 44). Currently in southern Italy the locals introduce the word cazzo, like an invocation, into the most common phrases: "Che cazzo vuoi" (what do you want).

PHALLUS WORSHIP

One century after the birth of Jesus, Plutarch reported that a mysterious voice, heard by a sailor, announced the death of the great god Pan. This news froze the Greco-Roman world with horror. The phallic god, the father of all the gods, risked dragging the civilized world with him in his fall, leaving men without protection. A new era opened up, full of dangers and conflicts, which little by little would lead to the extinction of the human race.

The phallus cult, born of the great religion that from Neolithic and Bronze Age times had spread from India to the farthest borders of Europe, remained anchored secretly in man's soul. Despite its persecution, we rediscover the cult of the divine phallus in rites, festivals, ceremonies, survivals, vestiges, and the traces it has left in its path, sometimes disguised but nevertheless always present.

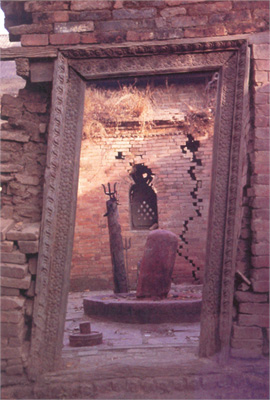

Nepal: Shiva lingam in Kathmandu courtyard. Photograph by Tara Hamilton.

Just as the eye, organ of vision, has the form of the sun, and the ear, organ of sound perception, has the form of the labyrinth, the form of the phallus, tree of life, whose sap gives birth to living beings, is the most fundamental of symbols. The form of the phal1us corresponds to that of the Universe. It represents the visible prolongation of the unknowable being whom, according to the Purusha Sūkta, "it surpasses in size by ten fingers" (atyatishtati dasangulam).

All ancient peoples endeavored to comprehend and analyze the characteristics of the organs whose union gave birth to living beings, and they reproduced the mystery by which the creator gave birth to the world.

Only he who worships the lingam, the upraised phallus within the vulva, respects the creative principle and, by means of this symbol, is capable of attaining divine reality.

"The lingam is an external sign, a symbol. However, it must be considered that the lingam is of two kinds: external and internal. The cruder organ is the exterior, while the subtle organ is the interior one. Simple folk worship the external lingam and concern themselves with its rituals and sacrifices. The goal of the image of the phallus is to waken the faithful to knowledge. The immaterial lingam is not perceptible to those who see only the surface of things. The subtle and eternal lingam is perceptible only to those who have attained knowledge" (Linga Purāna, 1.75.19-22,) "Those who practice the ritual sacrifices and faithfully worship the physical lingam are not capable of controlling their mental activity by meditating upon its subtle aspect.... Those who have not yet gained awareness of the mental sex organ, the subtle sex organ, must worship the physical sex organ, and not the reverse" (Shiva Purāna, Rudra Samhitā, 1.12.51-42).

By domination of the sexual instinct, we can acquire physical and mental prowess. Through sexual union, new beings can come into existence. This union represents a link between two worlds, a bridge where life is embodied and where the divine spirit is incarnated. The form of the organs that accomplish this ritual is the most important of symbols. They are the visible form of the creator. "By worshiping the lingam, one is not deifying a physical organ; one simply recognizes an eternal and divine form manifested within the microcosm. The human phallus is the image of the causal form present in all things. Those who wish not to recognize the divine nature of the phallus, who understand nothing of the importance of the sexual rite, who consider the acts of love as vile and contemptible or as a simple physical function, are certain to fail in their attempts at spiritual or material realization. To ignore the sacred character of the phallus is dangerous whereas by worshiping it one obtains pleasure (bhukti) and liberation (mukti)" ("Lingopāsanā Rahaysa").

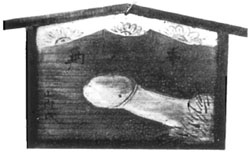

Japan: Wooden prayer tablet offered at Shinto sanctuaries. Photograph from Rufus Camphausen's Encyclopedia of Erotic Wisdom (Inner Traditions).

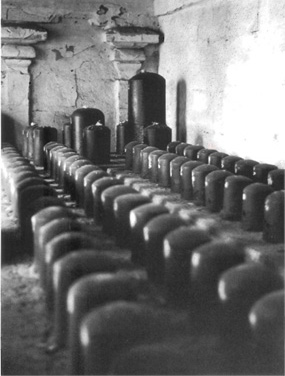

India: View of 108 lingams in a single shrine. Photograph by Nik Douglas.

Thailand: Shiva lingam near Buddhist shrine, garlanded with colored silks, flowers, and other offerings. Photograph by Nik Douglas.

"He who lets his life pass by without having honored the phallus is in truth a pitiable, guilty and damned being. If one were to weigh on a scale, with one side holding the adoration of the phallus and the other holding charity, youth, pilgrimages, sacrifices, and virtue, it would be the adoration of the phallus, source of pleasure and liberation, as well as a sure protection against adversity, that would outweigh the other side" (Shiva Purāna, 1.21, 23–24, and 26).

"He who worships the phallus knowing that it is the primal cause, the source of consciousness and the substance of the Universe, is closer to me than any other being" (Shiva Purāna).

The cult of the phallus is recommended in the Mahābhārata: "From whom comes the semen offered in sacrifice at the birth of the world in the mouth of Fire, the mouth of Agni, teacher of the gods and the anti-gods? Is the gold mountain Sumeru created from another semen? Who other than the ithyphallic god wanders naked throughout the world? Who else can sublimate his procreative power? Who else has made his beloved half of his self and cannot be vanquished by Eros? It is Rudra, the god of gods who creates and destroys. Can you thus see, O king of heaven, why the entire world carries the signature of the lingam and the yoni? You know as well that the changing worlds are issued from the sperm of the lingam during the act of love. All the gods, genies, and powerful demons whose desires are never slaked recognize that nothing exists outside of that-which-gives-bliss (Shankara) ... the sovereign of the worlds, the cause of causes. We have never heard that the phallus of anyone else was adored by the gods. Who is therefore more desired than he whose phallus is worshiped by Brahma, Vishnu, and all the gods, as well as yourself?" (Mahābhārata; Anushāsana Parvan, 14.211–232).

For the rites of lingam worship, the faithful brought fresh flowers, pure water, shoots of herbs, greenery, and sun-dried rice. They attached particular importance to the purity of the cult objects and to the physical cleanliness of the worshiper.

Why is the lingam worshiped? Because it is a symbol of permanence, an archetypical image that reveals the nature of the universal man, Purusha. To worship the phallus is to recognize the presence of the divine in the human. It is the opposite of an anthropomorphic monotheism, which is the projection of human individualism onto the divine. In the instrument of procreation we worship the creative principle, and we do this joyfully because this organ is also the instrument of a pleasure that for a fleeting instant gives us a glimpse of divine beatitude. The divine state is composed of three elements: existence, consciousness, and sensual pleasure (sat-chit-ānanda). Only sensual pleasure forms part of the domain of immediate experience. Therefore, by its intermediation we are able to sense, we are able to touch, the divine state.

The phallus cult implies the worship of harmony, the beauty of the world, the respect of the divine work, and the infinite variety of forms and of beings in which the divine dream is embodied. It reminds us that each of us is but an ephemeral being of little importance, that our sole role is to improve the chain that we momentarily represent in the evolution of the species and to pass it on. The cult of the phallus is therefore linked to the recognition of the permanence of the species in regard to the transitory nature of the individual, to the principle that establishes the laws whence we are issued and not their accidental and temporary applications. It is awareness of the life principle as opposed to the living individual, and of the abstract over the concrete. The worship of the phallus has implications on every level, whether of morality, ritual, cosmology, or society. Renouncing phallus worship in favor of a person, whether divine or human, is a form of idolatry, an outrage toward the creative principle. All the sacred texts of Shaivism, the Purānas, the Tantras, and the Agama tell us over and over again that only those who faithfully practice phallus worship will be saved, that all societies that draw away from the phallus cult and respect for physical sexuality are destined for decline and will be annihilated like the Asura, the race of men that preceded contemporary humanity.

India: Temple at Sangameshvara, early seventh century. Photograph by Lance Dane.

For the man possessed by the love of nature and the quest of the divine who successfully liberates himself from the taboos, superstitions, prohibitions, and myths of modern religion, the phallus—image of the creative principle—will appear anew as a luminous and eternal symbol that is the source of joy and prosperity.

Leonardo da Vinci noted, on several occasions, the respect that is owed to the virile member: "Man is wrong to be ashamed of mentioning and displaying it, always covering and hiding it. He should, on the contrary, decorate and display it with the proper gravity as if it were an envoy."

After a life of failures and setbacks on the religious, moral, material, and social planes, Maurice Sachs wrote:

"I hope to know no other temple than nature, to adore naught but the sun, to worship only the radiant member that creates man" (Le Sabbat, p. 177).

The Alexander of Michel Tournier's Les Météores (p. 105) proclaims:

"I cannot imagine God as anything other than a hard penis raised high, seated on the base of its two testicles as a monument erected to virility, the creative principle, the Holy Trinity, an idol of horn hanging at the exact center of the human body.... trifoliate flower that is the emblem of the passionate life, I will never be done singing your praises."