If he hadn’t had a flair for romance, Enrique Olvera might never have become a chef. Born in Mexico City, Olvera grew up in a household steeped in food. His paternal grandparents were bakers, and during summers he would work behind the shop counter and watch with fascination as the bakers kneaded the dough and transformed it into fresh bread. He would also spend hours roaming the Mercado San Cosme, known for the quality of its street food, which he ate with gusto.

But he didn’t get serious about cooking until he fell in love and began to make romantic meals to impress his high-school sweetheart (and now wife), Allegra. Those meals turned into a series of weekend parties for friends, and then their friends’ families, all of whom began to realize Olvera’s cooking talent. Some even became future investors. Although his parents expressed doubts about a future as a chef—“Working in the kitchen in Mexico seemed more the kind of profession you are obliged to execute, not a choice,” Olvera explains—Allegra encouraged him to continue, and Olvera became determined to show people that chefs could occupy a respectable place in society.

When Olvera told his parents that he wanted to study the culinary arts, his father, who had resisted taking over the family bakery himself to become an engineer, insisted that his son have at least a bachelor’s degree. Eventually they decided to send him to the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in upstate New York. Here Olvera learned European techniques, inspired by the chef heroes of the day, Jean-Georges Vongerichten and Thomas Keller, and entertained notions of working in a hotel or small restaurant.

One day at the beginning of his studies, his father was in New York City and invited him to lunch at a restaurant of his choice. They wound up eating at Le Bernardin, Eric Ripert’s three-star Michelin restaurant in midtown Manhattan. “It was impressive, like when you listen to your favorite band playing your favorite song,” Olvera recalls. One bite of the delicately cabbage-wrapped sole with foie gras he had ordered convinced Olvera that his future lay in fine dining. “I now knew exactly what I wanted to do.”

With six months left on his visa after he graduated from the CIA, Olvera went to Chicago and found a job at one of the city’s chicest French restaurants with the intention of learning everything he could. He was even able to stay in a small apartment owned by his dad, who went to Chicago often on business. “I was so lucky to be able to stay rent-free; otherwise I never could have made it work!” Olvera says now.

When Olvera first opened Pujol, the food seemed derivative of the haute cuisine techniques he’d learned in the United States. That’s when the chef had his second epiphany, realizing that he needed to combine Mexican traditions and techniques to create high-end Mexican cuisine that didn’t yet exist.

Take Olvera’s mole madre, mole nuevo, which reinvented the traditional Mexican chocolate and chili pepper sauce. The mole madre has been aged for over a thousand days: “Several years ago the cooks at the restaurant realized that if we reheated the mole for a certain amount of days, the flavor was more complex. So we decided to keep a small amount of it and to feed it with new ingredients,” he explains.

CURRENT HOMETOWN: Mexico City, Mexico

RESTAURANT THAT MADE HIS NAME: Pujol, Mexico City

SIGNATURE STYLE: High-end Mexican food

BEST KNOWN FOR: His one-thousand-day-old mole sauce at Pujol; his best-restaurant awards; his status as an ambassador of Mexican cuisine; and his many restaurants, including Cosme and Atla in New York City

FRIDGE: Sub-Zero

A few years ago, disappointed with the quality of Mexican cuisine in New York City, he opened another restaurant called Cosme (after his favorite childhood market) and Atla, an all-day café. His duck carnitas (cooked in Mexican Coca-Cola) and husk meringue and corn mousse dessert have become two of the most emblematic dishes on the menu at Cosme.

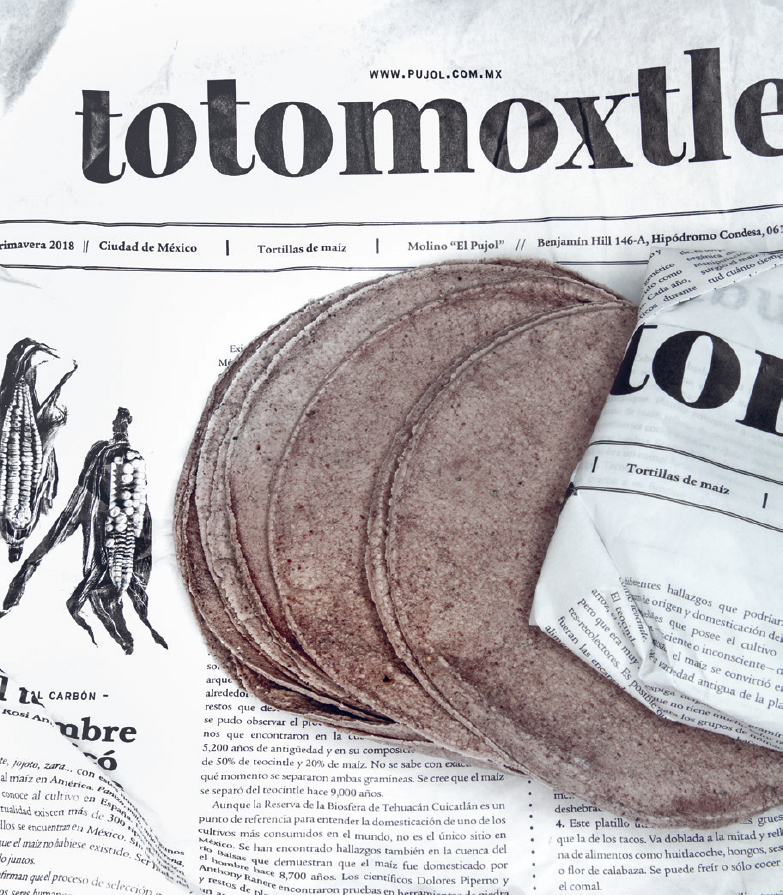

With seven people living at home, including his three children and two nannies, as well as thirteen animals, things can be as hectic as the restaurant kitchen. So food tends to be simple. “Our nanny is from Oaxaca and is a really amazing cook. But we basically eat tortillas and avocado three times a day,” says Olvera. Other daily staples are breakfast smoothies with nopales (cactus), blueberries, and chia; food swiped from the restaurant walk-in or smuggled from abroad.

- WHITE WINE

- WATER—“It’s very traditional here to put citrus and chia seeds in the water and we go through a carafe per day.”

- NOPALES—“I like them raw or just grilled, just with some key lime and salt.”

- EGGS, from the chickens in Olvera’s backyard

- BUNA COFFEE

- HOMEMADE SALSA

- TORTILLAS (blue, red, and yellow corn)

- FRUIT PÂTÉ—“This is a sweet, hard paste made of fruit for my children, who eat it just as it is for dessert.”

- BLACK BEANS—“We always like to keep some in the fridge, and often use them for soups.”

- PRICKLY PEAR—“Allegra likes them with eggs.”

- FRESH CHEESE

- SALTED PLUMS, for before-dinner snacks

- MORE TORTILLAS

- CHAYOTE SQUASH

- FRESH CHEESE

- CASTILLO DE CANENA EXTRA VIRGIN OLIVE OIL from Spain

- NOBLE TONIC 01 MAPLE SYRUP

- JUNE TAYLOR RASPBERRY AND LEMON VERBENA CONSERVE

- YUZU JAM

- CHOCOLATE ALMONDS from Casa Bosques

- HONEY

Q & A

Are you always so healthy? We don’t eat meat at home, only outside. So our home is pretty much vegetarian.

There’s no ketchup. Why? Here we don’t eat ketchup. Everything is salsa. I don’t really know what we would put it in.

Is that a prickly pear? Yes, that’s a chayote; we eat them either like that or boiled. We eat them with tacos. We eat everything with tacos. It’s the way of eating more than a dish. We never plate tacos. Since I was a kid, we basically have tortillas like this—we’ll have some sort of stew and serve it with tortillas.

What would people never find in your refrigerator? We would never have American cheese slices or leftover pizza. We don’t have milk, though we do have cheese. No sodas.

What about tomatoes? It depends how long you are going to keep them in there. If you are using them that day it makes no sense. But if they are already a little ripe then it’s better.

What is your family’s favorite meal when you’re the cook? Beef entomatadas.

You have lots of interesting things that don’t look Mexican. Do you bring a lot back from your travels? We are big food smugglers. Yesterday we smuggled potatoes from Peru. We also brought back some corn. We smuggle lots of food. When we go to New York, we go to Whole Foods and drag it back here to our fridge.

Is Mexican customs cool if you bring things in? I tried once, saying I was a chef. And they wouldn’t let me bring potatoes.

Do you have a couple of suggestions about cooking tortillas at home? You should never turn the tortillas more than three times over the flame. You can tell when the tortilla is cooked; it’s when the edges are turned up. It should be quick on the first side, ten seconds. Then the second side the edges puff up. The last side is ultra-fast, and then you’re done.

What were some of the first meals you cooked for your wife when you were a teenager? One of them was pasta, for sure, something simple, with vegetables since she was vegetarian at the moment.

Your guilty pleasure? Olives with a little Tabasco and lime as a snack before eating a meal—and ice cream while I’m watching a movie on Sundays.