When you ask Dan Barber about what led him to start cooking, he cites his mother, but not in the way you might think. “My mother passed away when I was four, so the origins of my becoming a chef might start there—overcompensating for the void,” Barber says. “I cooked a lot of grilled cheese sandwiches—English muffins with seven slices of Kraft cheese soaked in margarine. This was the seventies, after all.”

Another reason Barber started cooking early on: his father wasn’t adept in the kitchen. His go-to dish was scrambled eggs—made with margarine, no salt, and cooked to the point of no return. Barber thought that’s how all eggs tasted until an aunt cooked some when he was sick in bed with strep throat. “I’ll never forget the way she made them,” Barber recalls: “Whisked over a double boiler, finished with French butter and tons of herbs. They were so soft they slid down my throat. To be fair, I owe this memory to my dad. Without his butchered eggs, my aunt’s might never have made an impression.”

Another early influence was Blue Hill Farm, his grandmother’s farm in the Berkshires where he spent his summers. His job was to move the cows from field to field and make hay for the winter. One year cornfields replaced the pastures. “Riding the tractor, I never understood the importance of preserving a view like that until one summer, it was gone,” says Barber. “It felt so foreign to me—this thing that disrupted not just the landscape but what I usually did for the summer. And you couldn’t even eat it. It was grain corn!”

After college, Barber went to California to become a writer. “I thought cooking would be a good way to stay afloat. Write by day, cook by night. That was more or less my plan. At some point, the cooking just stuck.” During his twenties, Barber staged at Chez Panisse, and then attended the French Culinary Institute in New York City. Shortly after graduation, he left to work for Michel Rostang in Paris. “I went to Paris because in those days, you went to France to learn how to cook. I still think there’s no better training than the discipline of a French kitchen,” he says.

In 2000, Barber and his brother, David, opened Blue Hill in New York City. Barber had an unwitting commitment to locally sourced ingredients—an ethos that brought Blue Hill into the spotlight when Jonathan Gold of the Los Angeles Times first dined there. It was spring and the restaurant had accidentally doubled up on their asparagus orders. Barber refused to toss the excess. Instead, he transformed the menu into an ode to asparagus. Gold loved it. He lauded Blue Hill as the “farm-to-table” restaurant and, seemingly overnight, it became a sensation.

Barber believes chefs are in a powerful position to influence not only their menu, but also food trends and what’s sold in supermarkets and on TV. Last year, he launched Row 7 Seeds, a collaborative seed company. The project began when Barber met Michael Mazourek, a professor and vegetable breeder from Cornell University, and asked him why butternut squash doesn’t taste very good. The question inspired Mazourek to develop a smaller, more flavorful Honeynut squash. Now the goal is to do that for a wider audience—to create seeds that are tasty and sustainable and accessible beyond the world of fine dining.

CURRENT HOMETOWN: New York City

RESTAURANT THAT MADE HIS NAME: Blue Hill, New York City

SIGNATURE STYLE: Farm-to-table cuisine

BEST KNOWN FOR: Blue Hill at Stone Barns; his book The Third Plate; James Beard Awards for Best Chef (2006) and Outstanding Chef (2009); and his seed company Row 7

FRIDGE: Sub-Zero

“More and more, I’m realizing that the recipe for a dish begins long before an ingredient even enters my kitchen,” says Barber. “Really, it starts with the seed. With that in mind, we try to showcase the work of plant breeders and farmers by serving vegetables and grains unplugged and relying on the produce to speak for itself.”

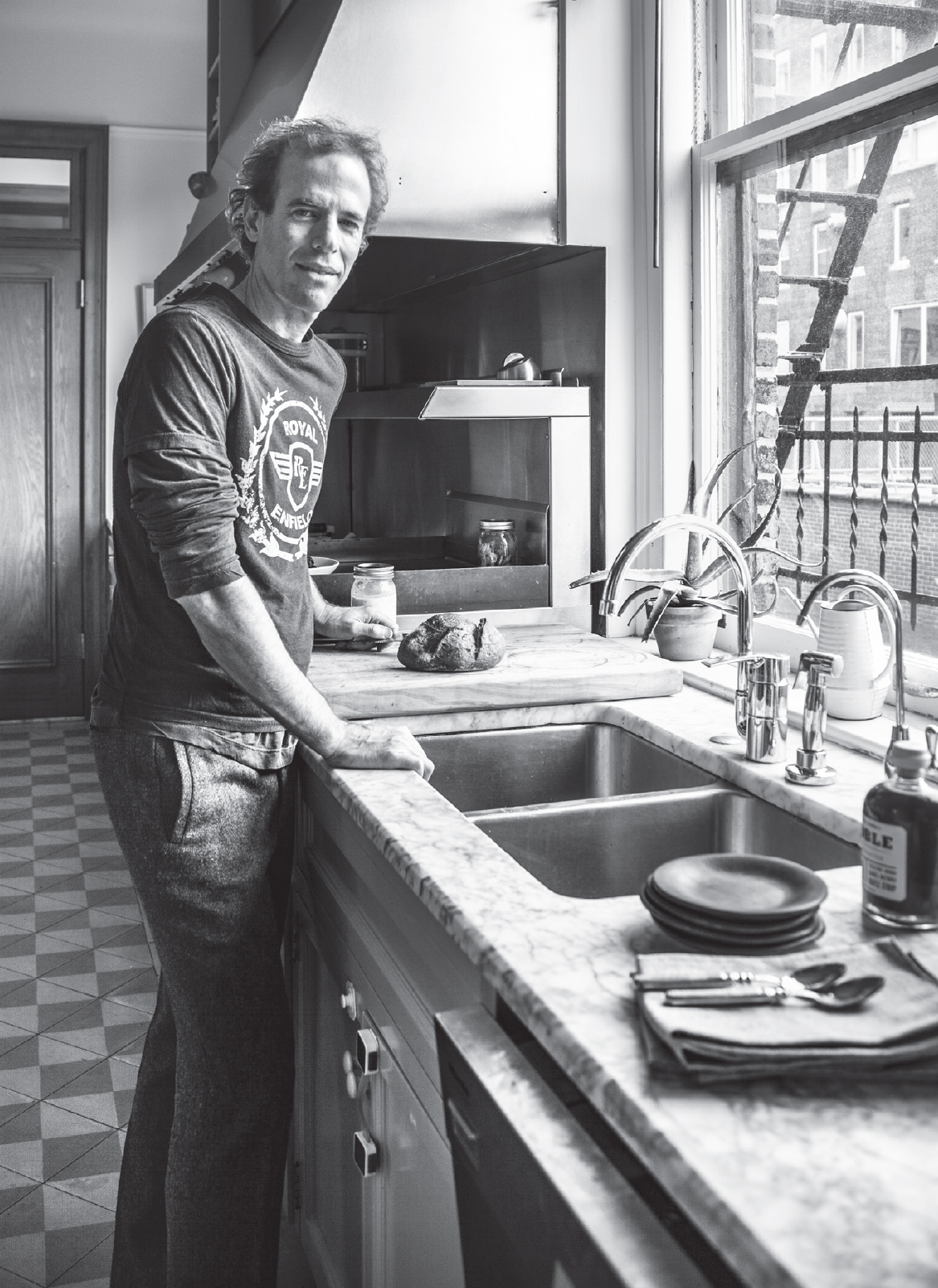

Seeds aren’t far from Barber’s thoughts as he prepares lunch for his two daughters in their sunny Manhattan kitchen, which has plenty of wood, mason jars, and kids’ drawings—and no fancy gadgets in sight. “I’m so much further beyond where I thought I would be in this business of cooking—beyond my wildest dreams, really. And yet, when I leave for work in the morning, my daughters give me this smothering hug, and no matter what I have ahead of me for the wonderful and grueling hours of cooking, I’ve already experienced the best part of the day. So there, that’s a hint for me on where I want to go,” he says. While we chatted, his wife, the novelist Aria Sloss, popped through the kitchen to put their youngest child down for a nap as Barber cajoled her sister to eat her sautéed broccoli, mushrooms, and bread.

- GRASS-FED RAW MILK FROM BLUE HILL—“My wife and kids go back and forth from raw to pasteurized. But I only drink raw milk.”

- KEFIR—“I like it on my oats in the morning.”

- PEPPER JAM—“We make that pepper jam at the restaurant from all the excess peppers from the fall. I keep it around in the winter for an extra kick of heat and sweetness.”

- FRESH MILLED WHOLE WHEAT FLOUR

- HIS WIFE’S YOGURT AND SOAKED OATS WITH DATES

- TOMATO SAUCE—“I made it with my older daughter, Edith.”

- COLD BREW COFFEE—“My wife turned me on to cold brew, but it’s fair to say she is the principal consumer.”

- APRICOT PITS

- GINGER AND TURMERIC—“My wife ends her day with ginger and turmeric grated into hot water, so we get them fresh at the farmers market.”

- RADISH KIMCHI—“We make a lot of sauerkraut at the restaurant, but I tend to just love other people’s kimchi.”

- DILL PICKLE SPEARS

- SOUR FARMHOUSE ALE—“It’s fermented with raw honey and conditioned in oak barrels for sixteen months. As I get older, I see the wisdom in always having a cold beer at the ready.”

- WHITE MOUSTACHE PASSION FRUIT PROBIOTIC WHEY TONIC

Q & A

You keep flour in your fridge? These are fresh milled whole-wheat flours. We need to get out of the habit of thinking about flours as staying on the shelf; they are alive and need to be chilled, almost like fruit. Taste this bread we make with it.

Wow, that is incredibly moist! The difference is that it’s fresh milled.

What do you usually eat for breakfast? I just love oats. It’s a nice thing to be able to eat something that you know is improving the health of the place where it comes from. Oats are a good example of a magic crop that adds nutrition to the soil instead of depleting it, like wheat, corn, and rice. We buy our oats from a friend and then get them malted. At the restaurant we ferment them with just a little salt and let them sit for a couple of days. Then we roast them.

Is that a jar of pits down on the lower shelf? I look at that every morning and get a little depressed as I was supposed to have done this project in the middle of summer with my daughter and we never got to. It’s all of the pits from the apricots in late July. When you take the pits and crush them with a hammer you get this almond flavor. Then you can infuse the pits—I was going to do that with milk or cream and make a dessert topping. But it was fun to save the pits.

Where do you shop for food? I go to Whole Foods and the farmers market on the way to school with my daughter. We get pastured eggs from Stone Farms and cheese down the street from Murray’s cheese shop.

What has been your biggest cooking fail at home? Lately it’s been a consistent string of failures to get my daughters to eat anything other than the daily predictables, like pasta and bread.

What do you wish your children ate more of? It’s more that my daughters go through these phases when they refuse to eat one thing in particular. Somehow, those phases have a way of aligning perfectly with when that one thing is in season. Like right now it’s spring and we just got in the first of the ramps—it’s such a small window when we can eat them. And of course, what does my daughter now suddenly hate? Ramps.

Why do you have so many live cultures like raw milk, kefir, and kombucha? These days, more and more people are interested in fermented and live culture foods because of their ability to activate our microbiome and improve our health. But I’m also interested in the flavor. When you ferment something, you catalyze a series of reactions that breaks down proteins and completely transforms the flavor profile of that food.

Is that Halloween candy in your fridge door? Yes, I used to have a terrible sweet tooth but the last few years it hasn’t been as sweet. I’m also a peanut butter junkie—but I don’t consider that to be junk food.