5

Great Weavings

Because the weavings are alive, they radiate the feelings of the weaver. Some people teach that you should not weave when you are angry or sad. The weaver should feel confident she is doing the right thing on all levels, that she is following the teachings. Then the weaving will contain good feelings, love, prayers, and protection.

—Chief Janice George, Squamish

A weaver is in almost constant motion—leaning in to look closely at the details and leaning back to see the entire surface. She checks the pull of weft at the selvage and makes sure the correct shed is open before beginning every “shot” of tabby or twill. Her hand passes over the warp threads at regular intervals to test for evenness of tension across the width of the fabric. The weaver must also frequently step away from the loom to see if the design, color, and proportions adhere to the original vision for the blanket. This final chapter steps in to see the detail and steps back to take a broad look at five of the great textiles created by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Salish weavers.

The Weaver’s Canvas

Threads of white wool wound around the upper and lower beams of a Salish loom can have the same appeal as a fresh, blank canvas. The weaver is free to create simple or complex patterns from the Salish iconography of straight lines, squares, triangles, and zigzags. Colors can be restricted to the customary red, black, and white of basketry or expanded to the subtle hues of plant dyes. Local stores sell yarns in vibrant colors to suit every occasion. Designs can come from patterns known to belong to a weaver’s family or may appear in the traditional form of a vision or dream. A common source of inspiration for new weavings is historical textiles. From the first of the weaving renewals among the Stó:lō to the most recent revival in Squamish, “great” blankets have inspired other weavers to study and re-create the designs. In the mid-twentieth century Annabel Steward wove a copy of the Perth Museum blanket based on the images and notes Oliver Wells made during his trip to Scotland. In the twentieth century contemporary Squamish weavers have reproduced design elements from the blankets worn by the Salish chiefs in the photographs taken in 1906. Some of these textiles were wall hangings made for display in public places; others were woven as personal regalia. Debra Sparrow from the Musqueam Reserve studied the blankets in Gustafson’s book and wrote,

Every time we stand in front of our looms, working with our wefts and our warps and mastering the tabby, we know that our ancestors used this same weaving. What were those women thinking about? Why did they weave this kind of geometric design? We don’t know that because it has not been documented. We are happy weaving and we don’t need to know. We will be respectful though. If we have to copy to get the influence and the inspiration that we need, then we will. We will pay attention as closely as we can, listen closely in quietness . . . paying attention to the messages that are being sent to us through our spirits and through our souls and our thoughts.1

Transformation Pattern

Perth Museum and Art Gallery 918.120

After standing for several hours to study this remarkable 1833 blanket, one of the authors sat down near the corner of the table and looked diagonally along the length of the textile. The rows of distinct patterning flowed into each other and the surface of the blanket looked like rippling water. The shift of the design from one visual state to another began our conversation about the role blankets play in ceremonial activities. We talked about how the blanket would look when worn in a public setting, lit by firelight, being danced, or glimpsed through a group of drummers, singers, or Speakers.

47. Transformation pattern, Perth Museum blanket. 918.120 Perth Museum and Art Gallery. Copyright and courtesy of Perth Museum and Art Gallery, Perth and Kinross Council, Scotland.

Mapping the Design

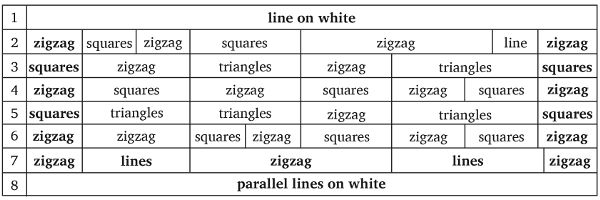

This textile offers one of the best illustrations of the relationship between blanket and woven bands, particularly tumpline designs. It is composed of eighteen stripes separated by narrow borders of plain white wool. The visually weak vertical elements, for example the stacked rows of colored lozenge motifs, do not distract from the strong horizontal lines. Large zigzags woven in the central bands are mimicked and reinforced by fine diagonal lines, which create miniature zigzag or arrowhead patterns on four of the thinner bands. These strong design elements attract the viewer’s attention to different areas on the blanket.

The design is repetitive, remaining fairly consistent in the details. Every band component is bordered by a red weft thread and isolated by four throws of white yarn. The weft rows in many of the bands involve a series of four repeats, a sacred number in Salish cosmology. For example, the sequence of motifs in one band composition has four rows of diagonal lines, four rows of columns, and four rows of opposing diagonal lines to complete the design unit.

It is presumed that the blanket edges without significant amounts of fringe mark the top and bottom of the robe and that the broad checkerboard pattern is meant to be worn at the shoulders. It is not known whether the weaver wove the textile from the top down or from the bottom up. Different traditions are practiced in Salish communities today. Squamish weavers usually weave down. Krista Point, a Musqueam weaver, has said that she was taught to weave from the base up.2

The dynamic rows of zigzags, lozenge shapes, and finely woven bands are framed by the patterns at the top and bottom of the robe. The starting and finishing edges of this blanket have fine white threads, followed by a red weft and a further border of white. The checkerboard top is separated from the rest of the blanket by a narrow repeat of columns bordering each side. On the blanket’s bottom edge the weaver has created a broad band of columns of different colors. The main body of the textile has four panels of large zigzags and four panels of lozenge-shaped design. The column motif seen at the top and bottom edges is repeated throughout the blanket but varies in choice of color and border. Figure 48 maps the blanket design.

Motifs

In the twenty pattern blocks that make up this blanket, there are three main motifs: diagonal lines, squares, and long diamond or lozenge shapes. The visual interest comes from the variation in color placement and in the change of motif size and shape. For example, the square motifs at the top of the blanket include narrow rectangles and equilateral blocks.3

48. Transformation pattern, design and color organization, Perth Museum blanket.

Colors

Each of the five complex patterned blankets discussed in this chapter appears to have its own palette. This may be the choice of the weaver or wearer, the result of the availability of yarns, or the fugitive nature of the dyes over time. The Perth blanket appears predominantly yellow, but this may not have been the original intention. Portions of the yellow areas between the zigzag points contain pale-blue threads. These may have been brightly colored at one time but are now faded. Red threads, which appear brown in many areas, may have once provided a stronger contrasting color.

The weaver’s original choice of colors for this blanket was probably white, red, yellow, dark green, and dark blue. These tones generally provide strong contrasts in a complex pattern such as this. In the zigzag section, for example, a red line is followed by white-blue-white-red. In the smaller stripes the eye is drawn to the contrasting color in the center band. The use of dyed threads to heighten the visibility of the small design can also be seen in the use of red yarn to delineate the edges of the lozenge shape. This outline technique is found on each lozenge shape in all four of the horizontal bands.4

The weaver has used subtle color blends in several areas. Careful study of the lozenge sections shows how the weaver applied red and yellow threads for different color effects: first as a muted color mix to the left of the lozenges and then on the right as a clearly delineated column of alternating wefts.

Fringes and Edges

The fringes on the blanket are longer than those on other complex patterned robes. They are created by extending the weft threads beyond the blanket selvage. The fringe threads are twisted and braided, a process that would have strengthened the finely spun wefts. An additional white yarn is wrapped the length of the selvages to secure the textile’s edge.

Economic and symbolic information are communicated through the use and amount of fringe on a garment. Extending beyond the edge of a jacket, leggings, or blanket, fringes serve no practical purpose as warmth or covering. Valuable mountain goat wool, dog hair, or trade goods are being consumed as decorative elements. As such, fringes are a visible form of conspicuous consumption, indicating the wearer’s access to an abundance of rare materials.

Symbolically, fringes are said to represent the closeness of the human and supernatural realms. The fluid extension of the threads as the wearers move or dance creates an interface between the person and the empty spaces that surround him or her. Chaussonnet argues that fringes serve as a metaphor for spiritual transformation.5 Fringes on robes also offer a visual confirmation of the belief that blankets are living objects. As the dancer sways or turns, there is a momentary delay in the subsequent movement of the fringe, almost as if the blanket is an independent being. Among the Haida, for example, a finished blanket is presented at a feast where it is formally presented to the community and given a name. It is then danced for the first time, and through the movements of the dance it is brought to life.

Double-Layer Pattern I

Pitt Rivers Collection 1884.88.9

This beautifully woven blanket suggests the idea of a double robe. The prominent black and white threads are carefully placed to indicate a border between patterned segments. This thick line draws a visual square in the center of the textile. The demarcation is placed across the top of the blanket, indented one vertical design row from the selvages and one design panel up from the lower textile edge.

This may be the first time researchers have noticed the Double blanket pattern. Gustafson considered this blanket as simply disorganized.6 Kissell called it a “less perfect design,” with stripes of the same width throughout.7 The current authors feel this blanket may represent a weaver’s early effort to create an illusion. It is certainly the most tentative of the Double or Framed blankets in its execution, requiring a visual reinforcement of a line made of black and white threads. However, the design shows a well-thought-out construction of motifs, with perhaps a few misjudgments in the spacing of the pattern blocks. The excellent quality of the weaving itself, and the imaginative use of color and motifs, suggest the work of an experienced weaver who was taking the traditional form of horizontal bands in a new direction.

49. Double-Layer pattern I, Pitt Rivers blanket. 1884.88.9 Pitt Rivers Museum. Copyright Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford.

The blanket was collected by Frederick Dally (1838–1914), whose short sojourn of eight years in British Columbia coincided with the height of the gold rush along the Fraser River. He arrived in Victoria, British Columbia, in 1862 and established himself as a local shopkeeper. In 1866 he opened a photography studio in Victoria and two years later launched a second one in Barkerville. Dally may have visited various Salish communities on Vancouver Island when he circumnavigated Vancouver Island onboard a Royal Navy vessel. He also had opportunities to visit Salish villages on the mainland. In 1867 and 1868 he journeyed to the goldfields at Barkerville, passing through traditional Salish territories on the way. He moved away from Victoria in 1870 to settle in Philadelphia for a time, eventually returning to England.8 Early cataloging data identifies the blanket as originating in the area of the Haro Straits, between southern Vancouver Island and the U.S. border.

Mapping the Design

The authors believe the top of this robe is the fringed edge with the single black line. The bottom edge, with the parallel stripes of black and red lines, serves as the lower frame of the design. The slight expansion of the width in this area may be to accommodate the design or to better fit a person’s body shape. Alternatively, it may be the result of an uncontrolled change of tension in the warp or weft as the weaving progressed.

The simplest component of this complex blanket is the under-robe. The two side panels mirror each other, giving the illusion that the lower blanket continues invisibly below the top textile, to emerge on the far side with a band of the same width and design. These side panels alternate the pattern block of a single zigzag line (which can also be read as a series of five elongated triangles) with a block of squares forming a checkerboard design. The bottom hem of the robe is all zigzags with two pattern blocks of vertical lines.

The over robe is less organized or consistent in its design. The sets of checkerboard blocks are almost uniform but are not precisely placed. The top row has one block of squares (seven columns by five rows) slightly off center, according to where the wearer’s shoulders would be. This band of weaving also has a smaller set of squares (five columns by five rows) to one side and a white stripe on the other. Three more checkerboards occupy the two sides (seven columns by five rows) and the center (nine columns by five rows) of the middle band. These are evenly spaced across the row and are separated by one zigzag design block. The final band has two checkerboard blocks and a line of squares that are not sufficient to create a complete checkerboard pattern. The second and fourth bands of the design combine rows of triangles with zigzag lines.

50. Double-Layer pattern I, design organization, Pitt Rivers blanket.

This blanket does not contain the symbolic repetitions of four or some variation of that number—such as two, eight, or twelve. The triangles are woven in a block of five or six, and the squares are sequenced in sets of five or six, depending on the row structure. Only the bottom band of the blanket shows the traditional number with four triangles that set off the zigzags and balanced stripes of two red and two black vertical lines.

Motifs

In this blanket the weaver has set all motifs against a white or off-white background. The lines, squares, and triangles stand out clearly, separated by a frame of white thread. The geometric choices are squares in checkerboards, triangles on the zigzag borders, lines of triangles all pointing in one direction, and straight and zigzag lines. There is uniformity in the numbers and sizes of the motifs when similar sections of the blanket are compared. Variations include the central checkerboard having one extra block and the absence of triangles on the border of the central zigzag patterns. The small blocks at the corner of the first and seventh row of the over-robe may have been miscalculations by the weaver.

Innovative shapes in this blanket, when compared to other large textiles of the period, are the slight shifts in the traditional Salish triangle and what appears to be the introduction of an entirely new design concept. Triangles are used here as part of the zigzag pattern, where they are woven at the edges of the pattern block. It is a traditional application of this geometric shape and is often seen in early bands and sashes. However, the vertical and horizontal rows of triangles that are used as a pattern block is an innovation. The shape of the triangle has also shifted from an equilateral shape to more of an elongated triangle.

The Danish National Museum holds a woven band with similar motifs and color application. It is documented as having been acquired during the 1838–42 Wilkes Expedition, deposited into the Smithsonian Museum, and in 1868 sent to the Danish Museum as part of an artifact exchange.9 The measurements (65 in. long × 3 in. wide) and long fringes (46 in. long) suggest it was used as a sash or belt. It is similar in materials and construction to the Wilkes Expedition belts discussed earlier (see chapter 4, figures 41 and 42). It is not clear where these textiles were acquired. The Peale catalog notes only that they are “belts made of the Rocky Mountain goat wool by the native of the North West Coast of America.”10 Walsh suggests that a number of Wilkes’s artifacts were gifts from Hudson’s Bay traders and may have come from areas not actually visited by members of the expedition.11

Colors

The blanket is in better condition than the Perth Museum robe discussed above and has less color fading and fraying of the fabric. The colors appear brighter and are easier to identify. The weaver’s choices of red, green, black, and yellow threads are similar to those used for other blankets from the same period. The clarity of the color against the white background is strengthened by the use of the same hue for each motif. Only a few of the squares or triangles are composed of threads of more than one shade. In these areas the colors are sequential across the motif, or a darker color is used to outline one or more sides of the form.

51. Double-Layer pattern II, Smithsonian woolen blanket. E1891 A-0 Department of Anthropology, Smithsonian Institution. Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution.

Double-Layer Pattern II

Smithsonian Collection NMNH 1891A-0

Looking at this blanket in Washington DC, we wondered why the weaver had placed a large white rectangular block at the base of the inset pattern. One speculation is that it represents the lower fringe of the superimposed blanket. The lines across the top, middle, and base of the under-blanket would be the borders that separated the over- and under-robes. The edges of the over-robe have stitching similar to that found on the Pitt Rivers textile. The blanket is a radical shift from the Perth blanket Transformation pattern (figure 47), with its of rows of small design elements placed as sequential woven bands. Instead, this blanket is a visual explosion of color and a dynamic design using traditionally arranged motifs in a blanket-on-a-blanket arrangement.

Smithsonian Institution cataloging information documents this blanket as collected by George Gibbs before 1866. Gibbs (1815–73) was a member of a wealthy New York family who attended Harvard University and worked for the American Ethnological Society before traveling to the California goldfields in 1849. He became an assistant customs collector for the Port of Astoria in Oregon and later joined the Northern Railroad Survey, the Pacific Railroad Survey, and the Northwest Boundary Survey as a geologist, interpreter, and mapmaker. Gibbs was a skilled linguist who conducted a census of the local Native populations, recorded ethnographic information, and participated in negotiations for treaty settlements in Washington territory.12 During his travels Gibbs collected zoological specimens for the Smithsonian and possibly acquired this blanket during the same period.13 In 1863 he returned to Washington and, in association with the Smithsonian, worked on dictionaries and word lists of Chinook, Clellam, and Lummi languages. He also prepared reports on Washington and Oregon ethnology and history.

Gibbs’s ethnographic observations included descriptions of handwoven blankets. He notes that the Indians in Washington Territory had almost completely adapted to European-style garments. However, blankets were still being woven of goat hair that was traded in from the Cascade Mountains.14

Mapping the Blanket

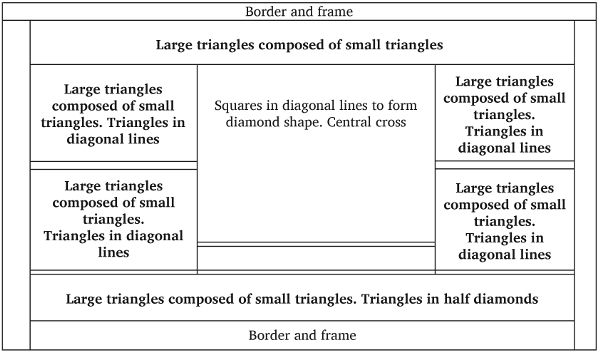

The authors presume that this robe would be worn so that the white rectangle, or “fringe block,” lies at the lower edge of the superimposed blanket. The two large triangles at the top of the main blanket would therefore be pulled around the wearer’s shoulders. The central top portion of the robe between these triangles would fold over as a collar.

52. Double-Layer pattern II, design organization, Smithsonian woolen blanket.

The blanket presents a series of frames moving from the outer edges towards the central rectangle. A narrow border, or band, of white tabby is followed by columns at the top and bottom of the blanket. The sides of the blanket begin with a narrow white border followed by a long red vertical line with rectangles on each side. Another border of white separates the outer frame from the start of the blanket pattern. The primary motif of the under-robe consists of variations of triangles: large and small, equilateral and right angle, inverted and upright. The band of woven designs at the top and bottom of the blanket contains two rows of large triangle shapes composed of smaller triangular forms. The top row has two completed V forms on each side, with the base of the V pointing down. Below is a central triangle and two half triangles on either side. These shapes have the V pointing up. Large triangular forms are woven to point inward on the side panels of the under-robe. They are bounded on each side with two or three parallel rows of triangles in diagonal lines. The only variations in the positions of the small triangles are two white triangles placed just inside the corners of the superimposed blanket.

The superimposed blanket form is unlike any earlier Salish blanket. The white blankets, the Fuca blanket style with the color confined to the borders, and the overall patterning of plaids or banded blankets distract the viewer’s eye away from the back of the wearer. In this blanket, however, the placement of the green cross highlighted against a white background draws attention to the wearer, rather than shifting it away. It is interesting that the cross line pattern rarely appears on Salish weavings. Haeberlin records less than twenty variations of this pattern among the more than eight hundred basketry and beadwork designs in his coiled basketry volume.15 He notes it is usually identified as a star symbol. Perhaps this blanket design reflects the presence of Christian explorers, fur traders, or early missionaries in the Native communities during this period. The artist, or the wearer, may have decided to incorporate this European symbol alongside traditional Salish cosmological iconography.

Motifs

The weaver of this blanket has created a clever and complex play of triangles and zigzags. As noted earlier, zigzag motifs offer weavers an opportunity to design creative, eye-dazzling patterns. On simple belts and blankets, colored triangular shapes typically filled the empty space created at the points of zigzag turns. In this blanket the triangles themselves are woven so closely that their intersecting forms create the zigzag. The top and bottom panels are nested triangles with the outer boundaries appearing as broad zigzag lines when viewed from a distance. A half-hidden black diamond shape is formed at each corner of the white “fringe” block, a pattern that the weaver was not able to replicate near the top corners of the superimposed blanket.16

Colors

Once again the colors are white, red, yellow, black, and green. There is some variation in the individual hues, possibly caused by differences in dye lots, fading, or wear. Each motif is woven in only one color and the forms are not outlined. The diagonal lines of triangles on the side panels are consistent in the alternation of white, red, yellow, and black. However, this pattern is not followed in other areas of the textile, for example on the over-robe. One aspect in which the weaver may have used color for symbolic purposes is the red line along all four sides of the blanket.

53. Framed pattern, Canadian Museum of History blanket. CMH II-C-853. Photographer: Steven Darby, 2016. Canadian Museum of History S94-36839.

Framed Pattern

Canadian Museum of History Collection II-C-853

In the authors’ database of patterned textiles is a set of blankets with similar designs, thought to have been woven in the 1860s near Yale or Spuzzum. Grouped by Gustafson into the category “Colonial,” the designs consist of a central square with a distinctive internal pattern set against a background of repeated motifs. There are approximately seven blankets of this style in museum collections and one pair of leggings made from pieces of a similar blanket. The most reliably documented textiles in this group are four weavings owned by the wife and daughters of Joseph McKay.17

McKay was a Hudson’s Bay Company trader and partner who explored new routes into the British Columbia interior. He served as an Indian agent in the Kamloops region and was a businessman who invested in land, timber, and mines. From 1865 to 1870 he was the factor for the trading post at Fort Yale on the Fraser River. It is thought that during this time he purchased or commissioned blankets from one or more local weavers in the area.18 In 1905 Charles Newcombe approached McKay’s widow and daughter to acquire one of the textiles for the Field Museum in Chicago. In a letter he refers to three blankets, which he had photographed for reference.19 He notes that “there were two with well-marked geometric designs and pretty fine quality” but felt that the prices were too high.20 In 1910 Newcombe and James Teit visited the McKays together to see the textiles. By 1914 the economic situation of the McKay women had become more difficult and they were ready to sell the blankets at prices the two museum collectors thought more appropriate. Teit negotiated with Miss McKay for four textiles, listing them as:

1. A small check design

2. The largest with fibre foundation

3. Medium short looped fringe vegetable fibre foundation

4. Eye design all wool21

Teit purchased two of the blankets on his list: number four for Homer Sargent, which was later donated to the Chicago Field Museum (catalog number 19133), and number two for Edward Sapir at the National Museum of Canada (now the Canadian Museum of History, catalog number II-C-679).22 Teit’s intention was to pick up the blankets in Victoria and bring them to Spuzzum on his way home to Spences Bridge. He hoped that someone might remember the name of the weaver, though he thought she must have died many years earlier. He wrote to Sapir,

If I could take one to Spuzzum to show the exact kind of specimen possibly I might get some woman there to undertake the making of one. Last year I asked one of the few blanket makers left there (the maker of the coarser ordinary type of blanket you saw in my place last fall) to make one of the McKay type but she said she was too old and it was too hard work. Some others I asked did not quite understand the type of blanket wanted. They said they might make a little square but I did not order anything.23

The collector and dealer Lieutenant Emmons was also interested in acquiring one of the McKay textiles. He purchased the textile Teit identified as McKay number three, a blanket now in the American Museum of Natural History collection (catalog number 16.1-1748). The Museum of the American Indian holds the blanket identified as number one, which was acquired by the museum in 1925 from Harmon W. Hendricks (catalog number 14.4864). The patterned blanket in the Peabody Harvard collection (catalog number 22-10-10-97917) is documented as collected at Fort Yale by the Hudson’s Bay Company chief factor Joseph McKay and is noted as probably made by the Thompson Indians.24 All of these blankets are similar in choice and placement of colors and design.

Two other blankets that are strikingly similar to each other in color and design are associated with the Yale Colonial-style blankets. However, they are not associated with McKay. One, found in the British Museum (catalog number N.1944 Am.2-198; figure 54), was probably collected by Lieutenant Edmund Hope Verney, who captained the HMS Grappler at Esquimalt, British Columbia, between 1862 and 1865.25 Verney was an active collector of Aboriginal material culture during his posting on the Northwest Coast. In a letter to his father dated March 26, 1864, he included a list of objects he was shipping home and noted, “The contents of this box, when added to what was sent home in the Princess Royal last year, and when are added a few articles I have by me at present, will probably form one of the best collections of the curiosities of this country that has ever been sent to England; and as these things are becoming more rare every day, and more highly prized by their possessors, it is not probable that so good a collection can ever be formed again, except at great expense.”26

54. Framed pattern, British Museum blanket. N1944 Am.2-198 British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

His “curiosities” ranged from bentwood boxes, masks, and bowls to soul catchers, charms, and regalia. Among the objects he sent back to England the previous year were a “semicircular rug of dog’s hair with a broad fringe” made by the “Northern Indians” and “one rug made of the skins of four mountain sheep.”27 A photograph of “The Museum” in his family home at Claydon House shows house posts from Comox, three Chilkat blankets (one of which may be the semicircular rug mentioned in his letter), painted boxes, and glass cases of smaller artifacts. In one corner is visible the geometric designs of a Salish textile.

Verney’s travels took him repeatedly to Salish areas, including the Cowichan Valley, Kuper Island, and Nanaimo. In 1863 he journeyed to the interior of British Columbia, traveling from Lillooet territory to Lytton and then passing south through Spuzzum and Yale on his way back to Vancouver Island. Unfortunately he does not mention the acquisition of artifacts during this period. In his letters home to his father he comments only on the scenery, his activities, and the Aboriginal people he meets.

An almost identically designed blanket is in the CMH collection (II-C-853; figures 53, 56, 57). Unfortunately, the information associated with this textile is unclear. It is listed in an early collection ledger, along with an equally undocumented white twill Salish blanket (VII-G-711). The surrounding entries list Northwest Coast material collected by Israel Wood Powell for the Geological Survey, the forerunner of the Canadian Museum of History. It is likely that the blankets formed part of this acquisition. Powell was an Ontario physician who, like Verney and Dally, arrived in Victoria in 1862. He became a wealthy landowner, a member of the legislature, and the Indian superintendent for British Columbia.

From this group of blanket types the authors chose the CMH textile II-C-853 for detailed analysis.28 It is a “great” blanket in the quality of the weaving, the choice of colors, and the imaginative design.

Mapping the Blanket

If it were worn, one possible positioning of the blanket would have the row of larger lozenges at the bottom edge of the textile. The two designs on either side of the central square would fold around the wearer’s body. This places the short fringes at the upper and lower edges.

55. CMH Framed pattern blanket, design organization.

Of all the blankets presented in the chapter, this textile has the strongest, simplest visual frame. Four broad lines, in the color sequence of black, white, red, and yellow, have been woven around the outer edges of the four sides. The internal square, the over-robe, is framed by a white-red-white border. An additional fine line of black thread marks the edges of both the under-robe and the superimposed blanket. The designs flow to the framed edge, giving an impression of diagonal lines and colored shapes extending beneath and beyond the well-defined lines of the over-robe frame. It thus appears as if the blanket continues below the central square, reinforcing the “blanket-on-blanket” symbolism.

56. Nested diamond row (detail of CMH Framed pattern blanket, figure 53). CMH II-C-853. Photographer: Steven Darby, 2016. Canadian Museum of History S94-36839 (detail).

57. Nested half-diamond row (detail of CMH Framed pattern blanket, figure 53). CMH II-C-853. Photographer: Steven Darby, 2016. Canadian Museum of History S94-36839 (detail).

Motifs

The design elements of this and other McKay-attributed textiles are similar in the simplicity and uniformity of the chosen motifs. A series of nested diamond shapes are the main format, with zigzags woven as triangles to border the edges of each shape. The framed central square has diagonal lines composed of small squares that draw the eye to a small central cross.

The row of nested diamonds (figure 56) in the lower and upper segments of the blanket foreshadows design elements found on the Delegation Blankets discussed in the next section of this chapter. In the photograph of the 1906 chiefly delegation (figure 18), the chief second from the right is wearing a blanket with a diamond-shaped pattern along the lower edge. The other blankets in the photograph showing the “Capilano-style” edging use a half-diamond variation (figure 57) of this nested motif.

Colors

This textile, like the one previously discussed, is woven using blocks of color. The shifting, subtle motifs of fine zigzag lines, the use of alternating weft shots to break up a color band, and the outlining of triangles found in earlier blankets are absent in this textile. Instead the weaver has depended on triangles of one color that reach into the neighboring spaces of a contrasting color to move the eye along the blanket’s surface.

This blanket is also notable in the weaver’s use of subtle colors, which create an almost three-dimensional effect on the surface of the textile. The repetition of primary design elements in softer hues has not been seen in other blankets of the study collection, except for the Perth Museum blanket (figure 47). The subdued colors work within this pattern, and the visual shifting of the lozenge form, with its spiky triangular edges, provides a visual flow or ripple effect similar to the 1833 textile.

The British Museum and the CMH textiles follow the traditional alternations of black and red. However, lines in the central frame and the motifs at the core of the diamonds are woven in black on the British Museum textile and in red in the CMH blanket. Given the almost identical pattern framework and the color choices, one wonders if they were made by the same weaver as a complementary set for an individual or a family or as a single commission.

One of the greatest challenges in the analysis of Salish patterned blankets is the absence of evidence regarding the place of origin. For the four textiles associated with the McKay family, Newcombe’s photographs and Teit’s discussion of possible weavers at Spuzzum provide links to a probable time and place of origin. It is not clear if these formally structured textiles were woven as commissions by McKay as rugs or simply acquired from Native families as interesting “curios.” Powell, Verney, and Dally all visited Yale, the final port of call for steamship transportation up the Fraser River into the goldfields. Unfortunately, it is not clear if the blankets they purchased were obtained at the time of their visit to this area, during their residence in Victoria, or during visits to other Salish communities on or near Vancouver Island.

58. Chiefs’ Delegation pattern blanket. CMH VII-G-334. Canadian Museum of History S92-3016.

Chiefs’ Delegation Pattern

Canadian Museum of History Collection VII-G-334

The historic photograph of the chiefs gathered in North Vancouver on their way to England in 1906 (figure 18) shows five of the men wearing or holding woven textiles with almost identical designs. On the far left is a man wearing a long woolen coat with woven sashes crossing his chest. The hem of the coat and cuffs of the sleeves have the undulating half-diamond pattern seen on several other of these robes. Unfortunately, the photograph is not clear enough to reveal whether the coat also has a set of the secondary side borders of linked hourglass forms. Toward the center (fifth man on the front row) stands Sa7plek (Chief Joe Capilano, 1854–1910) with a blanket of the same or very similar design folded over his arm. Next to him is Chief CalpaymalT (1810–1920), wearing a robe that is probably now in the MOA collection. At the right edge of the photo are two men wrapped in blankets. One blanket has the “Capilano Pattern” at the neck and hem with the double arrowhead motif on the side.29 The man to his right has a full diamond pattern along the hem and side borders.

The surprising uniformity of the designs suggests that one weaver alone, perhaps with the help of members of her family, produced these special robes. Squamish oral history states that these Nobility Blankets were woven by Squamish weavers. Documentation associated with the blanket in the MOA suggests that weavers from the Stó:lō area may have produced some of the blankets. The presence of robes with different designs suggests the activity of at least two other weavers in the Salish community with distinctive personal, family, or community design traditions.

These garments provide remarkable documentation for the study of Salish patterned blankets. They were perhaps the largest number of patterned blankets woven and worn during this period to express Salish cultural identity for a public audience.

The Salish blanket chosen for analysis in this category is a textile in the CMH collection, VII-G-334 (figure 58). The textile was collected in 1928 by Harlan Smith and the association documentation notes, “This blanket was worn by a Nanaimo chief to meet Sir Wilfred Laurier in 1911.”30

The blanket in the MOA collection woven with an almost identical design is identified as having been woven by Splaqlelthinoth, a Stó:lō weaver, and made in Chilliwack. The MOA label reads, “Blanket worn by Chief CalpaymalT (1810–1920) in 1906. He traveled to present petition to King Edward VII declaring that Aboriginal title was not extinguished. Blanket was inherited by his daughter Mrs. Willie George of Kosksilah Reserve. Purchased from her by person who sold it to Museum.”31

59. Billie Ycklum, Nanaimo. Photographer: H. I. Smith, ca. 1930. Canadian Museum of History Img72791.

Mapping the Blanket

This style of Salish patterned blanket is a simple rectangle with two wide, decorative borders along the length and a row of narrow motifs along the widths. The long edge, woven with a smaller, finer motif, is assumed to be the top of the blanket. It has seven repetitions of the black arrowhead design instead of the five repetitions at the hem.

60. Design organization, Chiefs’ Delegation pattern.

The patterned borders are separated from the twilled center by a line of black and white embroidery similar to that found on the Pitt Rivers and other mid-nineteenth-century blankets.

Motifs

The borders show a variation of the sharp triangular points found on earlier blankets. The geometric form has been woven to create a softer, almost undulating line. The nested forms of these half diamonds are bordered by triangular edging. Motifs woven in the center are stacked triangles or arrowhead shapes. The shorter sides of the blanket have a decorative border of double hourglass forms.

Colors

The colors follow traditional choices of red, black, green, and yellow against a background of white. The separation of red and black is maintained, with black forms isolated in white spaces and red triangles edging lines of green, yellow, or white motifs.

Great Blankets

This chapter has “stepped in” to look closely at the artistic choices earlier weavers made to “paint” their woolen canvases. The motifs and color choices of the Perth robe, with its finely woven tumpline-like bands, were transformed some thirty years later to become designs with sleight-of-hand patterns and dynamic flows of strong shapes and vivid color. It is also possible to see, over the same thirty-year period, the continuity of a traditional pattern, such as those on a woven belt in the Danish Museum, collected around 1838, and a blanket in the Pitt Rivers, purchased about 1867.

Today important Salish blankets are found in many places. The five robes chosen for analysis in this chapter are currently cared for in museum environments. When requested, they are brought out for visiting Salish weavers to study and are shared through loans for exhibitions in Salish communities. Contemporary blankets, woven as monumental works of art, are installed as wall hangings in university buildings, cultural centers, and public spaces such as airports and commercial businesses. The most valued contemporary blankets, however, may be those found in the homes of Salish weavers and of the people who have commissioned new robes to wear for ceremony and celebration.