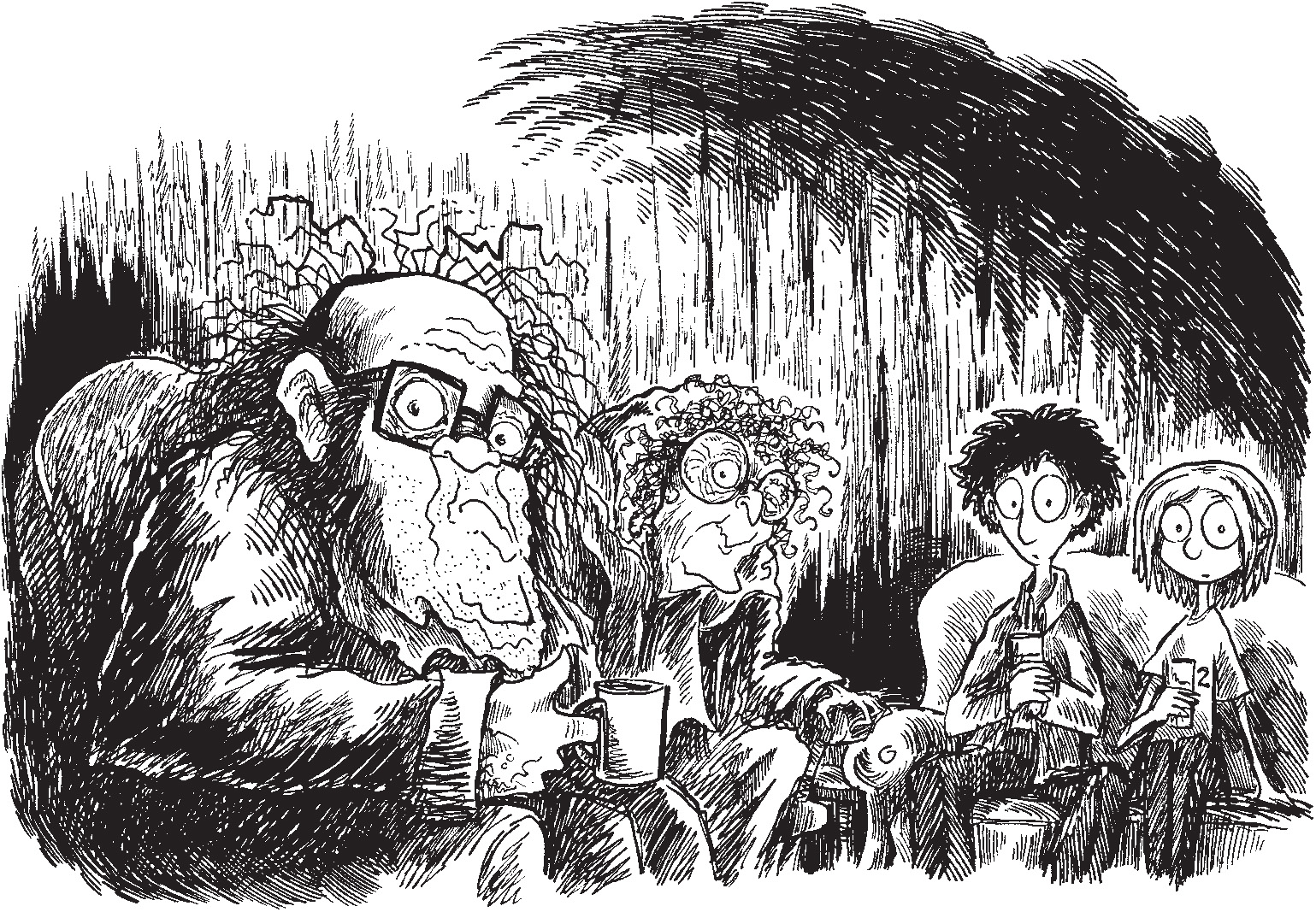

“I won’t sugarcoat it,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “Your sister was taken by the Boojum.”

“By the what?” asked Levi.

“The Boojum,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “It also took all the memories of you from your families and cohorts.”

“That’s what the Boojum does,” added Mr. Mushpit. “Steals away children, filches memories, leaves families with false recollections and a vague sense of emptiness.”

Levi’s stomach lurched. “You mean Twila’s . . . Twila’s . . .”

“Dead?” said Mrs. Mushpit. “No, no. Not yet, at least. The Boojum has her tucked away in its lair, alive and likely asleep.”

Alive. The word alone lifted a great weight from Levi’s chest.

“Aye, asleep,” said Mr. Mushpit. “But not safe. The Boojum will sap her, feed off her mental energy.”

“We saw it!” said Kat. “It came into Levi’s room at night! It was tall and shadowy! I shot it with a rocket!”

“Bah!” said Mrs. Mushpit. “That wasn’t the Boojum! Just one of its many underlings. The Boojum is fond of rallying the rabble to carry out its bidding while it hides in its lair.”

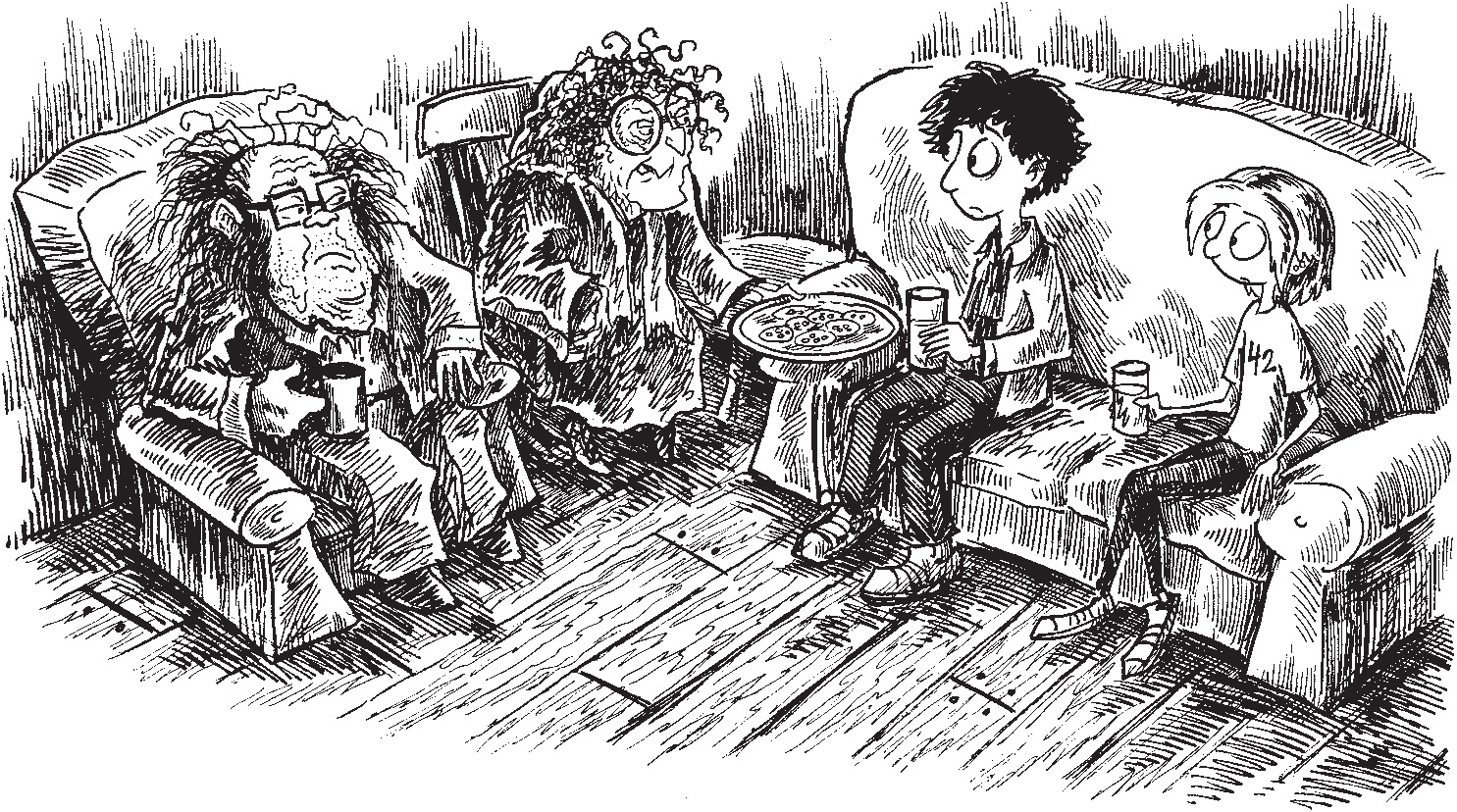

“Lair?” said Kat. “So it’s in the forest! I knew it!”

“Don’t be daft, girl!” snapped Mrs. Mushpit. “The forest is just a husk of its former greatness, but it’s still too wild for a calculating thing like the Boojum.”

“But we saw a monster in the woods!” insisted Kat. “This morning! Back by the marsh—something huge and horrible!”

“Ah. That was probably just Heckbender,” said Mr. Mushpit. “Pay him no heed. If you stay away from his bog, he won’t be a bother.”

“He seemed pretty dangerous to me!” said Kat.

“Naturally. He’d crunch your bones to paste if given the chance,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “So don’t give him the chance. He’s a tragic specimen, really. A relic.”

“But where are these monsters coming from?” asked Levi.

“Oh, there’ve always been monsters,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “There used to be a lot more of ’em, too. Sadly the world’s moved on, been sanitized. No room for anything strange in this modern era. And all that’s left are old fossils like Heckbender and miserable stowaways like your little goatsucker friend—eking out a sad living on the edge of existence.”

“And the Boojum,” added Mr. Mushpit.

“Aye, the Boojum,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “But the Boojum is a different sort of monster.” She saw the confusion on their faces and sighed. “I see. You’re young. Sheltered. Mayhaps we need to start further back.

“Funny,” interrupted Mr. Mushpit. “The sense of safety and order is likely the very thing that drew the Boojum here. It’s like with diseases: a vaccine may wipe out ninety-nine percent of a strain, but there’s always that one percent that survives, immune. Then as soon as everyone’s let down their guard, it swoops in to fill the power vacuum.”

“Don’t interrupt my elegant storytelling with your clunky metaphors!” snapped Mrs. Mushpit. She cleared her throat, opened her mouth, then scrunched her face in annoyance. “Ah. I guess that was all I had to say. Never mind.”

“Okaaay,” said Kat. “But you still haven’t told us what the Boojum is.”

Mrs. Mushpit’s beady eyes flashed. “Didja not hear a word I just said? It’s the one monster that thrives in safe, sleepy suburbia!”

“But what does it look like?”

“Hmm. There’s the rub,” said Mr. Mushpit. “As far as we know, it doesn’t look like anything. It’s seemingly non-corporeal.”

“Weird,” said Kat. “But where is it? If not the woods, then—”

“Think, girl!” clucked Mrs. Mushpit. “Under your very noses!”

“Don’t blame them, Olga,” said Mr. Mushpit. “It’s not like it’s some big scaly monster stompin’ down Main Street. It’s subtle. Invisible unless it wants to be found.”

“But what about Twila?” said Levi. “And the other children? Are they somewhere in town too?”

“Quite likely,” said Mr. Mushpit. “Stashed in its lair, where it can feed off the electrochemical pulses their minds produce.”

Levi’s brow furrowed.

“Well,” said Mrs. Mushpit, “you weren’t expecting it to chow down on burgers and soda pop, eh?” She paused and sighed. “Have we covered everything?”

Levi raised a timid hand. “Um, I was just wondering why, if this Boojum thing can steal and change memories, why—”

“Why you’re immune to the Boojum’s trickery? Why you remember what others have forgotten? Yes, that’s a noggin-scratcher.” She tented her fingers and fixed them with a piercing stare. “Why do you think you remember the taken?”

“Because,” said Kat slowly, “we are . . . the chosen ones.”

Mrs. Mushpit snorted. “That might just be the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard. You’ve been poisoned by Hollywood, girl. Don’t buy into prophecies, and don’t flatter yourselves. Keep thinking. What’s something you both share? A trait? An experience?”

“The garden?” said Levi in an unsure voice.

Mrs. Mushpit twitched an eyebrow. “Go on.”

“Um, so, both me and Kat got tangled in your garden. We got wrapped in ivy, scratched by thorns, breathed in the pollen. I still have a weird rash.” He pulled down his shirt collar to reveal the purple welts on his collarbone.

“Me too,” said Kat.

“Hmm,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “Our garden is different. None of those tacky retail-chain flowers you see in other yards. Our plants go back.”

“And plants have a certain magic,” added Mr. Mushpit. “Not a spells-and-wands-and-glitter magic. The magic of stars and water and life itself. Something the Boojum can’t fully grasp, despite all its cunning and calculation.”

“Spider-Man got his superpowers when he was bit by a radioactive spider,” said Kat. “We got beat up by a wacko garden.”

“An interesting hypothesis,” said Mr. Mushpit.

“Aye. So we’ve identified the situation,” said Mrs. Mushpit. “Now we move on to the best possible solution to your problem.”

But at that moment, there was a knock on the Mushpits’ front door.