5

There’s a Tavern in the Town

Lager beer of Best and Company 2 glasses for 5 cents! Morning lunch Evenings we invite you to enjoy humorous entertainment with piano accompaniment.

—Advertisement for A.C. Kuhn tavern in the Banner und Volksfreund (translated from the German), August 18, 1859

One can’t talk about Milwaukee’s beer and distilling history without discussing its noteworthy bar and tavern scene, which is first noted in 1837, when Louis Trayser opened his Zum Deutschen Little Tavern at State and Water Streets.1

As early as 1843, pioneer historian James Buck recorded 138 taverns in Milwaukee, an average of 1 per forty residents. Most were “rum holes,” rather like neighborhood taverns but less reputable. These dives got their name from cheap rum, which was liberally dispensed, and from their being dug back into the hillside along the Milwaukee River. The places were usually boarded up in front and had crude bars, over which was served low-grade home-brews and challet. This latter drink was a fearsome concoction of fermented wild berries, watercress, rum and limestone. The first German settlers around Milwaukee developed potent essig whiskey heimer, which first showed up early in 1839. Since no beer was initially available, farmers mixed whiskey and vinegar with a dash of ever-present limestone thrown in to put a “head” on it for added value. Many of the rum holes had back rooms, often dank tunnels, where the owner could store his stock. Some of these passages were jumbled with cots and straw ticks where men, women and children could lodge temporarily. Up to three hundred immigrants were arriving daily in Milwaukee and needed shelter; they usually headed to the closest place they could find near the docks. These “taverns” acted as social centers, banks offering short-term credit, travelers’ aid societies, forums and even as lovers’ rendezvous.2

At the start of the Civil War, historians estimated that there was 1 bar for each ninety-eight Milwaukee residents.3 The list of saloons in the city covered nearly three pages of the city directory in 1873, numbering 502 establishments. Newspaper reports related the economic importance of the beverage industry throughout this era. According to one account:

Allowing a fair average of $300 as the cost of each of these saloons, it will be seen that over $150,000 are invested in this business. These places employ about two thousand persons including the beer peddlers of our breweries, and at a fair average of three quarter-barrels a day, nearly four hundred barrels of beer are daily dealt out by the glass and by the measure. At ten dollars a barrel, the brewers receive a daily return of about $4,000 or about $28,000 a week. At a profit of three dollars a Quarter, about $3,000 are daily swept into the coffers of the keepers. As the profits on liquors equal that of beer, the sum of $10,000 is daily distributed in the way of profits by the bibulous portion of our community. In these estimates we have not included bottled beer and white-beer trade of the city.4

In the late 1800s Milwaukee, a drinker seeking a good thirst-quenching could select from at least thirty-five hundred drinking establishments ranging from the aforementioned dilapidated rum holes to fancy bars in highbrow hotels. About three hundred were owned and managed by women, most of them widows who had inherited the places from their deceased husbands.5 The plethora of bars extended well into the 1940s and 1950s and allegedly made it easier for Milwaukee native son and noted actor Spencer Tracy to occasionally—and only briefly—escape the long arm of his paramour, actress Katharine Hepburn, and the hounding of his press agents. It was said that Tracy often returned to the city, sometimes hanging out with fellow Milwaukeean and acting buddy Pat O’Brien. The two would “go to ground” at least for a couple of days of convivial conversation and genial cavorting before resurfacing as if nothing had happened.6

While most people enjoyed their beverages in a responsible manner, others needed some assistance with what could grow into a drinking challenge. There were several facilities where those in need could retire for drying out. In 1893, health services were added to the ministry of the School Sisters of St. Francis, with the opening of their Sacred Heart Sanitarium adjacent to the motherhouse on South Layton Avenue. The well-appointed sanitarium was the first of its kind in Milwaukee and became well known throughout the United States and Europe for its treatment of “mental and nervous disorders,” often a euphemism for alcoholism. No names were listed in the sanitarium’s record books, with “clients” noted only by a number tacked on the doors to the rooms.7

In 2010, the number of Milwaukee-area bars, taverns and other outlets selling alcohol was still impressive. With eighteen liquor-selling establishments, sixteen of which that sold beer and liquor and two that sold only beer, the Milwaukee suburb of Franklin had percentage-wise one alcohol-selling retailer for every 1,872 residents. However, twelve of these outlets were not taverns but gas stations, convenience stores or grocers. Despite this variety, it still meant that tiny Franklin had the highest concentration, in terms of population, among Milwaukee County’s nineteen municipalities. Wauwatosa was tied with Shorewood for second, followed by Hales Corners and then Milwaukee. Brown Deer had only one alcohol retailer for every 5,860 residents. River Hills had none at all. Milwaukee proper had 294 licensees for its 580,000 residents.8

The Scheneck and Schwindt saloon was one of the fanciest places in early downtown, a prime site eventually occupied by Gimbel’s Department Store. Visiting Gimbel’s years later, old-timers could still point out where the S&S bar used to overlook the river, where patrons watched the water traffic as they drank their beer. Later, Henry Wehr owned the saloon. Across the street was the upscale Browning and King’s haberdashery, in case a drinker needed a change of shirt collars. Of course, there were places more lowbrow, such as John Fogg’s Cannibal’s Rendezvous on Jones Island, where the Kashubian Polish fishermen gathered for their nickel drafts poured from barrels tagged as “wooden bladders.”

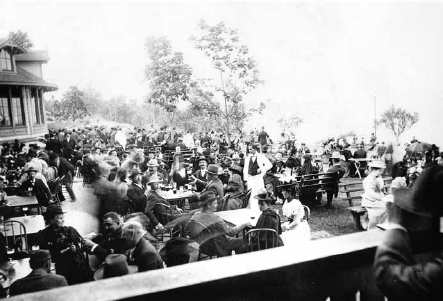

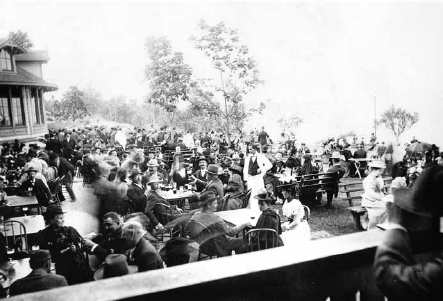

True to their heritage, the newly arrived Germans were also responsible for the biergarten, giant brewery parks that served gallons of beer amid potted palms and other expansive floral arrangements situated among the tables. Flotillas of waiters in starched white aprons sailed through the crowds, trays laden with steins carried by one hand high over their heads. In the days before child labor laws, the bucket boy, or kesseljunge, was given the job of rushing back and forth from the factory floor to the closest tavern. Others carried smaller takeout jugs nicknamed “growlers,” which are still popular at many Milwaukee brewpubs. Yet there were occasional limits. At the W. Toepfer & Sons Ironworks, beer drinking was limited to between 9:30 a.m. and 3:00 p.m. The Germans also loved picnics, concerts and Saengerfests, those family-oriented social events at which beer drinking and Gemuetlichkeit, or good feeling and fellowship, were linked.9

Terrace Gardens, a “public pleasure garden” and a popular venue for outdoor concerts and picnics by the community’s beer-imbibing Germans was landscaped on the site of pioneer settler Frank Lackner’s former home. However, in 1868, John Pritzlaff, a wealthy member of Trinity Lutheran Church who operated a wholesale hardware business, gave his congregation that large lot at the corner of North Ninth Street and West Highland Avenue, and the gardens closed. Yet despite the continued growth in the congregation, it took another ten years for construction to begin on the present church. When the cornerstone for the church was laid on July 8, 1878, an estimated one thousand people attended the ceremony. Trinity was designated a Milwaukee historical landmark in 1967.10

One of the most popular beer gardens was Quentin’s Park on Walnut Street, where locals held picnics and sipped refreshing beverages atop what was reportedly a Native American burial mound. Schlitz purchased the property and erected a fancy pavilion, with bubbling fountains illuminated with one hundred gas lamps, four white flagpoles at the entrance and full-throated opera singers for entertainment.

H. Kemper’s beer garden was built in 1850 in Milwaukee’s burgeoning main street business neighborhood. A short time later, the affable Pius Dreher built his beer palace beneath a stand of stately trees on the block bordered by State, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Streets and Prairie Avenue. The gardens sported five hundred tables able to seat three thousand persons. Another famous site was Ludwig’s on the River, at the Pleasant Street Bridge, where “in a setting of greenery and shade,” wine, ale and lager was served amid “a display of exotic and redolent plants.” Typical of the men who operated these facilities was Otto Osthoff, manager and lessee of an expansive outdoor playground called Schlitz Park. Osthoff was born at Bielefield, a village near Berlin, and served seven years in the Prussian army. In 1864, he came to America, landing in New York, where he remained for a year and a half. Osthoff meandered on to Rochester, New York, where he managed a hotel. In 1867, he came to Milwaukee and rented a small brewery, which he operated for three years. He then became manager and lessee of a Schlitz facility at Seventh and Walnut in May 1880. He and his partner, Jacob Litt, began presenting musicals and light opera there under the name Bijou Theater Company in 1893.11

The Whitefish Bay Resort, north of downtown Milwaukee, was a typical outdoors beer garden in the early twentieth century. Captain Fredrick Pabst opened the facility in 1889, attracting upwards of fifteen thousand people on warm Sunday afternoons. The resort presented concerts, offered Ferris wheel rides and plenty of beer. Visitors came via foot or bicycle, steam train or aboard the Bloomer Girl, an excursion boat carrying passengers from a downtown dock to the resort. Photos courtesy of the Historic Pabst Mansion.

Osthoff and his wife, Paulina Bittmann Osthoff, then built a hotel in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, in 1886. Originally called Hotel Münsterland, the name was later changed to the Osthoff Hotel. During the Prohibition era, it operated as a gaming casino and featured a well-known speakeasy drawing the uppercrust crowd from around southeastern Wisconsin. On a darker side, it was also allegedly a haunt favored by Milwaukee’s 1930s-era gangsters. Over the next generations, the property underwent a number of renovations, with the AAA Four Diamond Osthoff Resort and adjoining condos opening in 1989. The current facility maintains a Germanic theme, featuring the casual Otto’s Restaurant, along with higher-end dining.12

One of the most famous beer gardens, the richly ornamented Schlitz Palm Garden and Hotel, opened on July 3, 1896. An extravagant celebration staged on July 6 and 7 featured concert works by Offenbach, Zeller and similar notable composers. Designed by architects Kirchen & Rose, the skylighted space was replete with artificial ponds and plenty of gurgling fountains amid the abundance of flora.13 For the next quarter of a century, under the management of August Pleiss and Philip Heck, the garden attracted all ages and social strata of clientele who came to listen to Jos. Clauder’s Orchestra on the bandstand and to sip a brewski. Often, boatloads of tourists from Chicago took excursion boats for the day to visit Milwaukee and tour the Palm Garden. The pleasure palace was also the site of major conventions, such as those staged by the International Association of Fire Chiefs in 1911 and the Ancient and Honorable Artillery of Boston, plus sports banquets and other civic affairs that the Schlitz Brewery was happy to sponsor.

Knowing where to find Milwaukee voters, New Jersey governor Woodrow Wilson made one of his first campaign appearances at the Palm Garden in his bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in the 1912 White House race. Between three speeches he gave in Milwaukee on Sunday, March 24, just before he set out for a Pabst Theater appearance, Wilson asked to see the Palm Garden, the city’s most noted tourist attraction. He mingled with the happy crowd, but “the distinguished visitor did not try the brew,” according to newspaper reports. Perhaps that visit among Milwaukee’s dedicated beer drinkers and political activities helped Wilson secure his party’s nod at its August convention.14

Among Wilson’s opponents was the Progressive candidate Teddy Roosevelt, who, incidentally, was shot later that year in Milwaukee. On October 14, 1912, Bavarian-born John Schrank, a New York tavern keeper, wounded the Bull Mooser, who shrugged off the incident and launched into an extended speech. Also running against Wilson in that election was Socialist candidate Eugene Victor Debs, whose vice-presidential running mate Emil Seidel was a reformist mayor of Milwaukee from 1910 to 1912. Seidel, the first Socialist mayor of a major city in the United States, had just lost his bid for a second two-year term to Gerhard Adolph Bading, the son of a Lutheran pastor and a fusion candidate favored by Milwaukee’s joined-at-the-wallet Republican and Democratic business establishment.15

An able politician, first elected alderman in 1908, Seidel knew his constituents and their needs, often meeting with them in the city’s taverns and beer gardens. While the power structure didn’t care much for Seidel and his politics, the average Joe Beer Drinker thought the bespectacled, earnest former patternmaker was tops. He was considered one of them, although Seidel was a reformist who shut down Milwaukee’s brothels and gin mills along a wild stretch of the dockside Water Street. Locals loved him because Seidel’s accomplishments included introducing the country’s first workers’ compensation program in 1911, adult and worker education classes, free medical and dental examinations for schoolchildren and the first fire and police commission. So it seemed natural to honor the mayor in the best way possible. “Seidel” became the nickname for a beer mug, which in the minds of Milwaukeeans makes a much better memorial than a mere statue.16

After the Palm Garden was closed, the hall was renovated into the Garden Theater, showcasing silent movies and early talkies. It went through other morphings before being demolished in 1963. The Shops of Grand Avenue mall opened in 1982 on the site.

Enterprising Milwaukee brewers such as Frederick Pabst, always eager to expand his markets and show the world how to really drink beer, carried this garden concept elsewhere. In the 1890s, he traveled to Manhattan and set up a beer garden in Times Square, at “the Circle” at 58th Street and at “the Harlem” at 125th Street. He even imported a clutch of Milwaukee serving staff to show the New Yorkers “how to do it.”17

The city’s taverns and biergartens doubled as the era’s social centers, where Herr Schultz and Herr Schmidt could relax over their steins and rounds of card playing. While cribbage, euchre and poker were popular, sheepshead, or “sheephead,” was the game of choice, particularly among the Germans. This is a trick-taking card game related to the skat family, an Americanized version of a game that originated in Central Europe in the late eighteenth century under the German name Schafkopf. Although Schafkopf literally means “sheepshead,” the term may have been derived from Middle High German and referred to playing cards on an overturned barrel (from kopfen, meaning “playing cards,” and schaff, meaning “a barrel”—usually a beer barrel).18 At any rate, it was the perfect tavern game for fun-loving Milwaukeeans.

The city was dotted with these grand getaways, some more imposing than others, but each with its fan base. In the Menomonee River near the Melms Brewery “was a verdant spot ideally fit for the pouring fourth of the golden drink,” which eventually was replaced by a house. Some tavern structures had more ignominious ends once they outlived their usefulness. The Pioneer History of Milwaukee relates that “Belden’s Old Home Saloon, now No. 1 Spring Street, was removed this year [1896], July 14, to make room for the present block. It was placed upon a scow, carried to the South Side, and placed upon the west side of Reed street, near where the Union Depot now stands, where it was subsequently burned.”19

Milwaukee is still proud of its German bars and eateries, although they are becoming fewer and fewer, with the loss of such stalwarts as John Ernest Café, which opened in 1878 on East Ogden Avenue and closed in 2001. Another, Zur Krone, left its Walker’s Point Home in that same year, finding a new home in Thiensville, Wisconsin, where it eventually shuttered for good after several years. The cozy, original place, with its large round stammtisch in the corner window, was taken over by the Crazy Water restaurant.20

Mader’s may still be one of the country’s most notable German restaurants, opened in 1902 by Charles Mader and still operating in 2011. Originally called the Comfort, Mader boasted of his “soft” wooden chairs and oaken tables. Dinner, including tip and beverage, was twenty cents, and steins of Cream City beer were three cents each, two for a nickel. If a patron spent five cents on beer, his lunch was free. Originally on Plankinton Avenue, Mader moved his restaurant to North Third Street (now Old World Third Street). With Prohibition looming, Mader hung a sign in his window, proclaiming: “Prohibition is near at hand. Prepare for the worst. Stock up now! Today and tomorrow there’s beer. Soon there’ll be only the lake.”

When Prohibition’s screws began turning in 1919, Mader turned his attention to a big kitchen that became famous for the sauerbraten, wiener schnitzel and pork shank dished out in heaping servings. Since Milwaukeeans were never ones to forego a meal, even one sans beer, Mader’s did happily make it to that jubilant, cheering night of April 7, 1933, when its legion of barmen poured the first legal steins in the city. The end of Prohibition was announced at midnight from the restaurant’s commodious barroom via the city’s only radio station. When Charles Mader died in 1938, his sons, Gus and George, took over. Gus’s son, Victor, joined his father in running the restaurant in 1964, with the young Mader taking control when his father died in 1982. The Knight’s Bar at Mader’s remains reminiscent of an old-fashioned bierstubbe.21

Ratzsch’s Restaurant was launched in 1904, when Chef Otto Hermann opened his Hermann’s Café in downtown Milwaukee. A few years later, his stepdaughter, Helen, came from Germany to live and work in the café. Prior to World War I, Karl August Ratzsch Sr. was a young man touring the United States. Due to the outbreak of war, he stayed in the States, settling in Milwaukee, and began working with Helen. After a ten-year courtship, the couple married. They purchased the café and relocated it to the current location in the prestigious Colby-Abbot Building, built in 1883 on Milwaukee Street. The couple then changed the name to Karl Ratzsch’s. Karl (Papa) and Helen continued operation of the restaurant until 1962, when Karl Jr. became owner. His son, Josef, bought out Karl in the mid-1990s and sold the property to a new management team in 2003.22

To help keep their heritages alive, several of Milwaukee’s German cultural organizations built their own clubhouses, now open to the public. In 1934, several Bavarian societies leased the property between the Milwaukee River and Port Washington Road south of West Silver Spring Drive. By 1943, the club had built several high-quality soccer fields and a huge dining room with a large bar offering German and local beers. The original clubhouse is now the site of the La Quinta Suites. The property was sold in 1967, when the United German Societies built the Bavarian Inn at 700 Lexington Boulevard. The club’s fifteen-acre Old Heidelberg Park, with its stages and gazebo, hosts festivals, dances, picnics and other events in the true tradition of Milwaukee’s German community.23

The Donauschwaben Vergnügungsverein and three other Donauschwaben clubs—the Apatiner Verein, the Mucsi Familienverein and the Milwaukee Sport Club—opened a complex in the mid-1960s. Serving a population of Germans whose ancestors once lived along the Danube River in the old Kingdom of Hungary, the complex in Menomonee Falls has a restaurant, halls to rent, a picnic area and soccer fields. It is much like the traditional beer gardens of previous generations.24

Several other German taverns and beer halls survived the years, including the venerable Kegel’s Inn, established in 1924. Now managed by Rob and Jim Kegel, the building still has its original leaded glass and heavy wooden beams.25 Paul Elhlert managed several bars on the East Side, one of which was a tavern at 1216 East Brady Street, now housing the Up and Under Pub, one of the city’s premier blues clubs.26 Nodde’s Bar at the corner of Warren Avenue and Brady Street was another local hangout in the 1950s and is now called the Nomad World Pub, the first of several bars owned by tavern/eatery entrepreneur Mike Eitel of the Diablos Rojos Restaurant Group.27

If one knows what to look for, numerous “tied house” taverns are still readily seen around Milwaukee. These were bars owned or operated by the breweries, selling only that particular brand. Some of these remaining buildings were mapped and annotated by the dedicated supporters of Milwaukee’s Museum of Beer and Brewing, a group eyeing part of the old Pabst brewing complex for its eventual home. Most of the structures the group has identified still have brewery company emblems over the doors, on the outside walls or on the roofs.28

Schlitz, Best (later known as Pabst) and Blatz brewing companies purchased some two hundred corner lots in 1884 alone. An article in the Milwaukee Sentinel stated that the fact “that there should be room for a saloon for every 130 inhabitants (including men, women and children) has given the city the name of being the saloonkeeper’s paradise.” The article continued, saying that it

is hardly possible, however, that all of these saloons could be profitably continued were it not for the backing of the brewers. The brewers have invested an enormous aggregate of capital in the business of brewing beer, and have a vital interest in having the demand for beer kept up. Within the past two years, the export trade has been affected by a more active competition, and in order to utilize the full strength of their productive facilities, local brewers have seen the need of maintaining the home trade.29

Rather than merely supplying stock and fixtures to saloonkeepers who might otherwise prove untrustworthy or unbusinesslike, the breweries took it upon themselves to erect their own tavern buildings with the result that “[I]t secures the erection of better buildings in place of the wretched structures occupied by the proprietors of low grogeries, and better order will be maintained.”

All this development was viewed with skepticism by the paper, which commented that saloon sites were being acquired even in the better residential portions of the city and “every property owner knows that they do not enhance the value of his adjoining property, and although he may be a good patron of the saloon, he does not care to have it for his next door neighbor.”30

Early in his career at Schlitz, company president Joseph Uihlein led the drive to purchase such strategic corner locations around town. Uihlein realized he needed to secure these sites for building saloons to sell the Schlitz brand. This aggressive push thus edged out his competitors, who were also eagerly seeking to entrench themselves in the market. Schlitz’s prime real estate holdings proved to be valuable when the brewery was forced to suspend beer production during Prohibition. When the cash-strapped company needed a financial kick during the ensuing Depression, many of its locations were subsequently sold to oil companies for their gas stations. Despite losing these valuable properties, it was a necessary procedure. The money garnered from the real estate transactions helped keep Schlitz afloat in the financially grim 1930s.31

Several of the Schlitz locales remain bars or have morphed into restaurants. The Little Schlitz Pub at 2501 West Greenfield Avenue, later became Benjamin Briggs Pub. A blue and white ceramic Schlitz mosaic still adorns the outside wall near the front door, and there’s a faded ghost sign—“Drink Schlitz”—on the west wall of the building.32 Among the early proprietors who ran the tavern were Henry Raasch (1905–06); Joseph Zdroyk (1907–08); Louis Mikulecky (1909);Joseph and Helen Zdroyk, later a widow (1910–11); and William Schaefer (1912–20). The 1920 city directory indicated that the place had become a soft drink parlor, mostly likely because of Prohibition’s regulations.

In 1922, the building, sans its bar or saloon fixtures, was sold to Frank and Mary Patock, who continued to run it as a soda fountain. After her husband’s death in 1924 and with the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, Mrs. Patock obtained a permit to operate the facility as a tavern and remodeled it in the style of an English inn. In the late 1940s, the building went through a succession of owners, including Walter and Rose Orlowski and George and Phyllis Schauer. The building, designated a Milwaukee Historic Site, was purchased in 2009 by Raul Varela Rodriquez and renamed Club Fiesta. All managers and owners over the years demonstrate the changing ethnic demographics of its South Side neighborhood.33

In the late 1990s, Dave Sobelman and his wife, Melanie, restored a marvelous old Schlitz tavern at 1900 West St. Paul Avenue, deep in the industrial Menomonee Valley. Factory workers mingle with faculty and students from nearby Marquette University, office personnel, truckers and others from all walks of life flocking to Sobelman’s for its giant hamburgers. A large Schlitz globe logo can be seen on the third-floor façde.

The Three Brothers Serbian Restaurant at 2414 South St. Clair Avenue in Bay View also sports a giant Schlitz globe atop its cupola entrance, hence its original name: the Globe Tavern. The hospitable restaurant’s low-key charm, augmented by made-from-scratch burek, musaka and kashkaval, has earned raves from Gourmet magazine, Bon Vivant and other foodie publications. The father of current proprietor Branko Radiecevich purchased it in 1950, shortly after the family emigrated from war-torn Yugoslavia.

A former Schlitz tied house can still be found at Holton and Clarke at the north end of the Holton Street Bridge, at 2414 South St. Clair in Bay View. A giant Schlitz Globe is perched on its rooftop. Schlitz built another Mike Eitel property, the Trocadero at 1758 North Water Street, for barkeep Frank Druml in 1890 for $8,000. The building was also a rooming house for newly arrived immigrants who worked in the tanneries across Water Street. The Main Event, a now-shuttered blues and jazz club at 3418 North Martin Luther King Drive, was also once a tied house.

Club Garibaldi at 2501 South Superior Street is just across the Hoan Bridge spanning Milwaukee’s harbor in Bay View. In 1908, the building opened as a tavern whose then-owner eventually moved farther down Russell Avenue. He opened another bar in the neighborhood made up predominately of Piedemontese Italians. The Schlitz Brewery eventually took over, adding the expansive wood bar still seen today. A back hall was added in 1927, and the Giuseppe Garibaldi Society, a fraternal order formed by northern Italian immigrants, began meeting there. The society purchased the building about 1941, leasing the tavern operation to Tag Grotelueschen and Joe Dean, two former East Side bartenders at the Points East Pub on Lyon Street.34

Among the remaining Pabst tied houses is Regano’s Roman Coin at 1004 East Brady Street, a well-known East Side landmark at Astor and Brady Streets. Originally topped by an ornate cupola, the structure was built in 1890 by well-known architect Otto Schrank, who also designed the Pabst Theater. The use of such professionals was typical of the breweries, which wanted to ensure the highest-quality look for their properties. Joe Regano purchased this building in 1996, and his daughter, Teri, is the current owner.35 Restorante Bartolotta at 7616 West State Street in Wauwatosa was also a Pabst tavern, as was Slim McGinn’s Irish Pub at 338 First Street. The latter building had formerly been owned by Milwaukee restaurateur Johnny (Johnny V) Vassallo, who operated it as Smugglers. Richard (Slim) McGinn was the former bar manager at the Harp on Juneau before branching out on his own.

A Miller tied house can also be found at the corner of Hubbard and Garfield in the aptly named Brewers Hill district, once home to numerous brewery managers and workers. Nearby is the building once housing the fabled Humboldt Gardens, another Miller tavern at the corner of Humboldt and North Avenue. In another life, it morphed into Zak’s nightclub and was unoccupied as of 2010. A windstorm in late 2010 peeled off much of the Cream City brick façade.

NOTABLE MILWAUKEE BARS

Not long ago, a flatlander from New Lenox, Illinois, visited an in-law on Weil Street in what was once a Polish working-class neighborhood now called the more neutrally encompassing Riverwest. He stood in the middle of the intersection and marveled that there were taverns on each corner and one in the middle of every block as far as he could see. Each establishment had its own fiercely dedicated clientele.

In the early twentieth century, Milwaukee licensed 2,440 taverns, 6,767 bartenders, 2,630 pinball machines, seven horse-drawn junk wagons and fourteen handcarts. Author and Democratic political operative Harold Gauer published a series of books about growing up on Milwaukee’s East Side in the 1930s and 1940s, with some of his best tales focusing on the city’s taverns. “For some good souls, it was a confessional. For the depressed, it was a pool in which sorrow was drowned, and for boasters, appreciative listeners were always there. The tavern served all the purposes of the classic Greek marketplace, the desert oasis, and the baths of ancient Rome,” Gauer rhapsodized.36

In the 1930s, taverns were usually in clapboard buildings, unlike the more genteel tied houses of the previous generation—although schweinbacke (hog jowls) and bratwurst perfumed both. Among the better-known hideaways were Ernie & Mary’s, Frank & Sally’s, Sophie’s Place, Shorty’s Doghouse, Ma’s, Joe’s, Steve’s and others of that ilk. Emil Koeller’s roadhouse gardens on Green Bay Road offered plenty of cheek-to-cheek dancing when Belly Snider played the piano and Uncle Nats set forth on the drums. There, the waiters serving beers, Old Farm rye whiskey and sloe gin didn’t need any experience. The joke was that if wait staff applicants could walk without falling over their own feet, they got a job.37

Dirty Helen’s Sunflower Inn on St. Paul Avenue opened in 1926, serving no food but sneaking drinks to its more upscale clientele. During the Depression, “Dirty” Helen Cromwell, a devotee of Old Fitzgerald bourbon, gleefully served abundant amounts of what she exclaimed were “hard drinks for hard times.” The Sunflower shuttered in 1959. Peter and Mary Sigan opened Mary’s Log Cabin tavern and restaurant shortly after World War I at Clinton Street and Greenfield Avenue. It became a rooming house during Prohibition. Peter died in 1933, and typical of the day, his widow carried on, becoming noted among the factory workers at nearby Allen Bradley plant for her “Deep Fat Fried Chicken Jamboree” served on Saturday nights.38

During the late 1930s, up-and-coming young politicos, writers, musicians and artists congregated at Colla’s Five & Dime Tap near the near East Side tanneries. Owners Marcella and Francie Colla waterfalled giant tappers and served “Texas and Shoes,” their signature hamburger and shoestring potatoes. The place was popular, especially since a glass of wine was five cents, a mug of beer was ten cents and cocktails peaked at twenty-five cents. A hungry cub reporter from the Hearst-owned Milwaukee Sentinel could buy a hard-boiled egg for a nickel or a ham sandwich basted in beer sauce, sparked with ring of pineapple studded with cloves—all for ten cents.39

Checking out leftovers from a night’s fun in the mid-1930s, Harold Gauer (right), Bill Williams and Robert Bloch consider the woes of their frivolity. Bloch went on to be the writer of Psycho, the basis for the frightening film of the same name by Alfred Hitchcock. Photo courtesy of Harold Gauer estate and Precision Process/Urge Press.

In the 1940s, Barney and Emmet Frederick managed the tiny Wayside Inn in a downtown alley at Number 1 Northwestern Lane, frequented by journalists, lawyers and others of similar ill-repute. Emmet died in the South Pacific during World War II, but Barney kept plugging away for another decade. Regulars kept track of their own drinks by marking their names on whichever liquor bottle they favored.

Smiley’s Tavern on Vliet Street put a different twist on the saloon theme, specializing in wine, Gauer recalled. “He had barrels of them laid on their sides in tier and tapped from the barrelhead with spigots. There was a choice of white port, tokay, muscatel, zinfandel, claret and a dozen other varieties, all tasting remarkably like sweet soda pop needled with spirits. A glass was five cents, and a gallon could be had for sixty-nine cents, but drinkers had to bring their own jug.”40

Other popular taverns in the 1930s included Jordan’s Café at Plankinton and Wells, noted for its marvelous mahogany bar and hearty servings of excellent pea soup. At the Big Stein, also on Plankinton, drinkers could throw their peanut shells on the floor and sip their beer from frosty stone mugs. At Wendelin Kraft’s cocktail bar on Jefferson Street, fresh milk was available for teetolating Socialists off duty from city hall. Six-time mayor Dan Hoan and eventual mayor Frank Zeidler, both good, squeaky-clean Social Democrats, were among those who gathered there to talk strategy with their cronies. The Sixteenth Ward Democratic Organization met regularly at Gaynor’s Tavern on Twenty-seventh and Wells, while the Twenty-sixth Ward diehards wandered to different watering holes, usually “with more beer on the way…leaving things pretty hysterical.”41

Scribe and pub-crawler Gauer died in 2009, leaving much of his estate to the Milwaukee Press Club, of which he was a lifelong member. The organization is the longest continuously operating press club in North America. After a series of moves, it is now tucked into the first floor of the Fine Arts Building at 137 East Wells Street, across the street from the ornate Pabst Theater. Since 1885, the press organization has collected signatures of notable personalities, from presidents to burlesque queens. Many of the autographs are exhibited on the walls of the club’s venerable Newsroom Pub, where the city’s advertising and public relations crowd hangs with staffers from nearby governmental offices and area journalists. Gauer’s donation was used for scholarships, programs and related activities sponsored by the club.

The Newsroom Pub is now managed by the Safe House, which opened in the lower level of the Fine Arts building in 1966. The latter nightspot is secreted behind an entry to what is mysteriously called International Exports, Ltd. A password is needed to get in the narrow entrance from the Front Street alley. The haven is a favorite of off-duty, real-life Secret Service agents and other security types accompanying major dignitaries, including whoever is the occupant of the White House at that time visiting Milwaukee. Two secret passages connect the Newsroom Pub and the Safe House, allowing for quick getaways after a round or two.42

Bowling, beer and Milwaukee go together. Brew City’s Holler House is the oldest certified bowling alley in the United States and contains the two oldest sanctioned lanes in the nation. Both alleys are still tended by real, live pinsetters. In 2006, the tavern was rated by Esquire magazine as one of the best bars in America.43 Holler House was opened by “Iron Mike” Skowronski as Skowronski’s Tavern on September 13, 1908. By 1912, the price of a roast beef sandwich had soared to a quarter. Allegedly during Prohibition, liquor was stored under a baby’s crib in the backroom, supposedly because the local police wouldn’t look there and risk needing to calm a screaming little one. Skowronski’s son, Gene, and daughter-in-law, Marcy, took over in 1952, renaming it Gene and Marcy’s, the latter managing the bar after her husband’s death. About 1975, the place was nicknamed “Holler House” by a neighbor. Holler House sells only bottled beer, with the exception of Schlitz in a can. Among its notable keglers and gutter-ballers were professional bowler Earl Anthony, who amassed a total of forty-three titles on the Professional Bowlers Association tour; guitarist Joe Walsh; actress Traci Lords; and Frank Deford, a Sports Illustrated senior writer and National Public Radio commentator.44

Koz’s Mini Bowl at 2078 South Seventh Street is another iconic bar-bowling alley. With its four short lanes for duckpin bowling, Koz’s is one of the last remaining such sports bars in the country. The balls used in duckpin bowling weigh two to four pounds each, have a maximum regulation diameter of five inches and don’t have finger holes. Local kids still set the pins at Koz’s, much as was done in the 1880s at the height of the game’s popularity.45

The Landmark Lanes, in the basement of the Oriental Theater, dates from 1927, when the Theater and Bensinger’s Recreation were built on the site of the former Farwell Station, a horse, mule and streetcar barn. When Prohibition gasped its last breath, the wild and woolly Club Silver opened in Bensinger’s. The place was sold to United Artists in the early 1950s, making it the only theater in the nationwide chain complemented by a bowling alley. In 1973, Pritchett’s Jazz Oasis swung wide open there, featuring formidable guitarist George Pritchett. Over the next several years, the room featured local and national jazz performers. Demonstrating its lure for all types of Milwaukeeans, in 1979, the Lanes hosted the first Holiday Invitational Tournament, the city’s premiere gay and lesbian bowling tournament. In 1980, the Jazz Oasis reopened as a second bar and dart room. In 2002, then-owners the Pritchett brothers sold the theater and lanes to New Land Enterprises, with Slava Tuzhilkov assuming a majority position. As the Landmark approached its centennial, famous visitors included feminist Gloria Steinem, numerous athletes and dozens of politicians looking forward to its beer pitcher specials and Bloody Marys. Entertainers performing in the bar area have ranged from the Dixie Chicks to Todd Rundgren and Nora Jones.46 These days, moviegoers at the upstairs Oriental can purchase wine to sip while viewing the latest Academy Award nominee.

Hooligan’s Super Bar at 2017 East North Avenue has been a fixture on the East Side scene since 1936. It now boasts twelve big-screen televisions and more than thirty micro and import drafts, plus the usual selection of local brews. In the old days, Hooligan’s was more of a shot-and-beer place than a sports scene. In one incident in those revered days, a motorcyclist allegedly maneuvered his big iron up the front steps of the triangle-shaped building, roared through the bar, grabbed up a stein of frothy beverage and rumbled full throttle out the back door. The procedure was done with finesse, without running over any patrons or knocking over a stool. According to the story, a number of the diehard patrons didn’t even notice.47

Tiny, but fabled nonetheless, Wolski’s is Milwaukee’s longest-running family-owned bar, found at 1836 North Pulaski Street. “I Closed Wolski’s” is a catch phrase printed on vibrantly colored bumper stickers found worldwide, from Hollywood to armored Humvees in Baghdad’s Green Zone. Celebrating its 100th year in 2008 under the same family lineage, Wolski’s remains a combination snug, caravansary, cozy front room, therapist’s office and neighborhood hangout à la Cheers of television fame. Wolski’s is owned by Dennis Bondar and his brothers, Mike and Bernie, who grew up and still live nearby.

Their great-grandfather, Bernard Wolski, a city fire hydrant inspector, opened his bar in 1908 at the foot of the steep Pulaski Street hill a few blocks north of Brady Street. The year before, the Polish émigré moved the former retail store there from another lot, using horses and roller logs. Over the ensuing generations, a succession of great-uncles and other relatives ran the bar, with assorted children, spouses and cousins also working there. The tavern was taken over by Michael and Bernard in 1973, when Dennis was a teenager. He became a partner when in his twenties. All work the bar, taking various shifts and dividing managerial duties.

As with many longtime Milwaukee bars, Bondar retained a dedicated help staff, such as longtime bartenders Paul Johnson and Angela Cooper and doorman Tony Miller, each of whom has been there for more than a decade. Those familiar faces, plus the general geniality packed into about one thousand square feet, means Wolski’s is the quintessential Milwaukee tavern. Part of the basement still has its original dirt floor, where the cool temperatures there make for perfect beer and wine storage. Old boxing and political posters, photos of Wolski’s fans in exotic ports of call and other memorabilia paper the walls.

A good bartender needs a good ear, a feature that retains patrons of all collar colors, whether blue, white, pink or other. Over the years, the brothers have become fast friends with folks such as Eddie Lebanowski, a retired postman who died in 2007 at age ninety-two. For decades twice a week, Lebanowski and his wife, Gertie, walked to Wolski’s for his favorite drink, a whiskey press. Over the years, thousands of Milwaukeeans and assorted star guests, such as the fabled Father Guido Sarducci (comedian Don Novello of Saturday Night Live notoriety) have counted Wolski’s among their favorite watering holes.

The “I Closed Wolski’s” phrase came about in the 1970s, when Mike’s rugby-playing pals flocked to Wolski’s to replay matches over plenteous beverages. Late one night, a patron suggested the motto, and it immediately took off, with Wolski’s ubiquitous bumper stickers sprouting like mushrooms around the world. Friends and patrons still carry them on military tours of duty, on vacations and business trips. The tavern also has the de rigeur T-shirts and even lady’s thongs, all designed and produced by longtime friend, John Behling of Oostburg’s Mount’n Screenery. Obviously, such items show up in the most interesting places, indeed.

Since none of the unmarried Bondar partners has any kids, although Michael and Bernard have longtime girlfriends, the bar ownership may eventually pass on to one of their three sisters’ children.48 Always promotions-minded, Wolkski’s did have one major roadblock in its history.

The Milwaukee Police Department began aggressively enforcing tavern capacity laws in 2007, judging overcrowding by square footage, number of exits and number of restrooms. Concerned about the growing popularity of its annual pub crawl, which could have made it an easy mark for a fine, Wolski and several other area bars canceled their ever-growing spring event that year, when the participant count began hitting the thousands.49 All has since been resolved, and life happily proceeds as before.

The building housing Fitzgibbons’ Pub at 1127 North Water Street has another illustrious history, housing what many consider to be the city “oldest gin joint.” The structure was built in the late 1800s for Weisel’s Sausage factory. When that company moved to a larger facility, the building was converted into a bar shortly after the end of Prohibition and subsequently housed a number of taverns under different names ever since. Over the years, it was noted for being “the real deal for real men who drink real drinks.” Daniel Fitzgibbons opened it as Fitzgibbons’ Pub in 1998, boasting Milwaukee’s only outdoor pool table, plus loads of free advice and criticism and, thank heavens, indoor bathrooms. According to Fitzgibbon, “If you want blended drinks, go somewhere else. We don’t have a blender.”50

Mike Roman loves his beer—and history. He has plenty of both at his Roman’s Pub, at 3473 South Kinnickinnic Avenue, which was originally a stagecoach stop and roadhouse dating to 1885. A great neighborhood saloon, this long-ago speakeasy featured a regularly rotating roster of up to thirty often hard-to-find new draft micros on a regular basis. The pub was owned by the same family from 1919 until purchased in 1978 by Mike Roman, who began specializing in craft beers in the mid-1990s and then added cigars and wines to his stock. He had no problem with the state’s smoke-free legislation, either. Puffers sit out on his heated back deck and order beverages through a window, “just like Dairy Queen.” Only peanuts, chips and assorted snacks are available, but Roman allows food carry-ins and even provides the paper plates. Decor remains eclectic, with loads of beer memorabilia, old advertising and drinking-related paraphernalia. Although the building can be easily missed on a quick drive-by, the elaborate Paulaner Munchen bracket with its Romans’ Pub signage hanging above the entrance is the landmark.51

What’s a city without its Irish bars? Among those in the Milwaukee area claiming a Celtic link are Mo’s Irish Pub, Judge’s, Brocach Irish Pub, Trinity Three Irish Pubs, the Black Rose, Halliday’s, the Blackthorn, Murphy’s, McBob’s and Caffrey’s. Some are more faux Irish than others, but the craic—the good times—still roll on regardless of owner ethnicity and number of televisions on the walls.

Milwaukee has long had a heritage of Gaelic drinking establishments, particularly in the era of the Civil War, in what was then the rough, tough, “Bloody” Third Ward. With its grogshops and dives, the neighborhood ranged along the Milwaukee River and was noted for being one of the toughest districts in the city. In the mid-1800s, Chief William Beck’s beat cops, brawny lads such as the iron-knuckled Tom Shaugnessey, earned their thirty dollars a month the hard way. They were expected to whomp any miscreants as much as necessary before hauling them off to the hoosegow.52

Among the early Irish tavern keepers was John McCarthy, who became proprietor of the famed Union House after a stint as a Great Lake sailor and Civil War veteran. Ireland-born John Curran ran a bar and billiard parlor on Lincoln Avenue, while Richard Casey, who launched the Milwaukee chapter of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in the late 1880s, operated a saloon at 67 North Third Street. Tom Doorley (sometimes spelled Doerly or even Doerley) operated a bar at 196 Erie Street. His father, Martin, was Milwaukee harbormaster and a color sergeant in the Union Guards who drowned in the sinking of the Lady Elgin steamship on Lake Michigan on September 8, 1860.53

That sinking was a disaster for Milwaukee’s Irish community and changed the city’s ethnic face. A state historical plaque near the Irish Pub at 124 North Water Street is not far from where the Lady Elgin sailed on its ill-fated voyage. The pub building dates from 1904 as a Pabst tied house and workingman’s hotel, with a Pabst logo still seen on the south wall. The structure also once housed a dockers’ bar called the Captain’s Table and for thirty years was home to the city’s longest-running gay bar. The Irish Pub opened its doors in 2007.54

Each year, the pub regulars raise a toast to the long-deceased who drowned on the doomed Lady Elgin. There were nearly four hundred confirmed deaths, making it the greatest open-water loss of life in the history of the Great Lakes. Among the dead were brewer John P. Engelhart; Lacy Lasky, the Elgin’s bartender; and a number of Milwaukee’s best-known, politically connected tavern keepers and saloon owners.55 The 150th anniversary of the Lady Elgin sinking was marked on September 8, 2010, with the premiere of A Rising Wind, presented by the Damned Theatre at the Best Place Tavern in the renovated Pabst Brewery complex.56

Legendary Christopher (Kit) Nash initially operated a pub in his hometown of Dublin, where he had also operated a bar. Coming to the United States, Nash opened Nash’s Irish Castle, at 1328 West Lincoln Avenue, in the mid-1970s. Now a Mexican bar/restaurant, Nash’s was home to numerous Irish-born and wannabes. It was a snug haven in which to meet, sip beer and listen to live music; it was also one of the first places in town to offer vinegar with its french fries in fine Gaelic tradition. With his wife, Josie, running the operation from behind the bar, Nash held court from a stool at the far end of the room. At closing time, everyone knew it was time to go when Nash stately rose from his perch and announced, “Have you no feckin’ homes to go to?” Another admonition was offered to ensure a successful entrepreneurship, “Own your own building and have no partners.”57

Danny and Helen O’Donoghue were proud of the restaurant and expansive bar they operated on West Blue Mound Road from 1986 to 1996. Coming to Milwaukee from Killarney in 1949, O’Donoghue owned a popular State Street pub for a number of years even while working as a laborer and foreman at the nearby Miller Brewing Company. O’Donoghue partnered for a time with his uncle, Big Jim Hegarty, who also owned nine other bars in Milwaukee since his first pub in 1939. A formidable figure who kept a baton under his backbar in case of trouble, Cork native Hegarty came to the United States in 1926, after fighting and being wounded in the hand during in the Irish Civil War. His final bar, located near Marquette University and a popular hangout for decades of law students, was called Flanigan’s for years before Hegarty bought it in 1972.

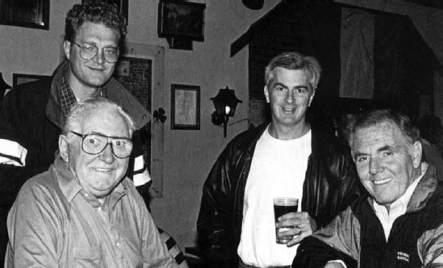

Ray Flynn (seated at right), three-time mayor of Boston, dropped in at Kit Nash’s Irish Castle on Milwaukee’s South Side to encourage support for Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton. Flynn eventually went on to be Clinton’s ambassador to the Vatican. Dublin-born Nash (seated at left) grinned as the pints circulated. Joining Flynn and Nash were then Milwaukee major John Norquist and former alderman Kevin O’Connor. Photo by John Alley, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

Big Jim died of a heart attack in his tavern in 1981, and the space was then sold, closing in 2010 after the then-owner filed for bankruptcy. Yet carrying on the family tradition, Danny and Helen O’Donoghue’s son, Jamie, owns O’Donoghue’s Irish Pub in Elm Grove, still offering lively music sessiúns and strenuous rounds of set dancing.58

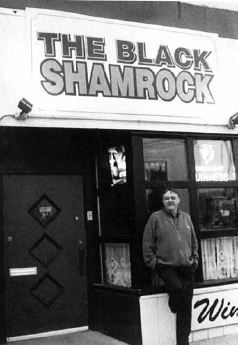

Milwaukee’s Irish bars have not only been watering holes but literary and artistic centers as well. In the early 1990s, Tom Connelly’s late, lamented Black Shamrock on Milwaukee’s East Side and Cecilia’s Pub, managed by Kerry Wiedemann on South Second Street, attracted large crowds for music, poetry readings and theatrical presentations.59

Owner Rip O’Dwanny has the corner on Irish inns. Among them is the County Clare, which opened in 1996 at 234 North Astor Street. O’Dwanny’s also owns 52 Stafford in Plymouth, where each room is named after an Irish personality, and St. Brendan’s Inn in Green Bay. For a number of years, O’Dwanny also operated the Castledaly Manor House in Athlone, County Westmeath. The inn was located not far from Locke’s Distillery, an Irish institution that traces its roots back to 1757. O’Dwanny’s Milwaukee caravansary remains the “snug” for many of the city’s Irish-born jackeens and bogtrotters. Dublin-born singer Barry Dodd is a regular performer.60

Josie Nash of Nash’s Irish Castle received a warm hug from Finbar MacCarthy, who first began singing in Dublin pubs at age twelve. Josie and her husband, Kit, were both born in Dublin and were among the principal advocates of Irish music in Milwaukee for decades. MacCarthy left Ireland in the early 1980s, performing in bars in the Canary Islands and then entertaining elsewhere throughout Europe. He eventually wound up in Wisconsin and opened his own bar in Saukville, a town just north of Milwaukee. Photo by John Alley, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

Danny and Helen O’Donoghue ran the show from the vantage point of their restaurant on Blue Mound Road from 1986 to 1996. O’Donoghue came to the United States from Killarney, County Kerry, in 1949 and became a laborer and foreman at Miller Brewing Company. He partnered for several years with his uncle, Big Jim Hegarty, a County Corkman who was then “chieftain” of the Milwaukee Irish bar owners. The O’Donoghues’ son, Jamie, owns a bar in Elm Grove, a western Milwaukee suburb. Photo by the author, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

A native of County Cork and another nephew of the aforementioned BigJim Hegarty, Derry Hegarty came to the States in 1965, taking over Feeney’s for Fun Bar from Joe and Mae Feeney in 1972. Hegarty’s sister, Margaret, ran the nearby Mr. Guiness [sic] Tavern for a number of years, a happy place that was the initial planning base for the Milwaukee Irish Fest, now the world’s largest Irish cultural event. Greeting guests for years at the bar rail was Muldoon, Hegarty’s longtime St. Bernard pal, known for his affection for beer. An adjoining hall has long been a major hot spot for political fundraisers and other rousers, whether Veterans for Peace or the Emerald Society. Hegarty remodeled the banquet area with $96,000 from winnings he garnered at a Las Vegas slot machine.

Owner Tom Connolly stands outside his Black Shamrock pub, a feature of Milwaukee’s East Side bar and arts scene in the early 1990s. Connolly regularly hosted Celtic-themed theater presentations, poetry readings, photo exhibits and music in his place, a block north of the entertainment hub along East North Avenue. Photo by the author, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

Cary (Rip) O’Dwanny received his nickname for his prowess in batting baseballs as a youngster on Milwaukee’s East Side, not far from where he operates the County Clare guesthouse. The County Clare, which opened in 1996, remains a social center for Milwaukee’s émigré Irish community. Long active in the bar, restaurant and hotel business, O’Dwanny first renovated the 52 Stafford, an Irish inn in Plymouth, Wisconsin, the oldest continually operating hotel in the state. He then moved on to open other hospitality facilities, including St. Brendan’s Inn in Green Bay and Castledaly, a restored manor in Athlone, County Westmeath, Ireland. Photo by Dan Hintz, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

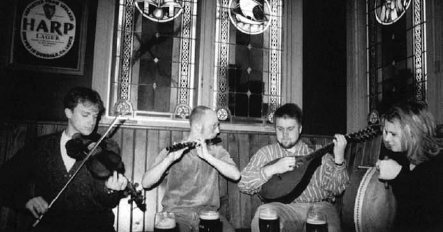

The rousing Irish band, 180 & the Letter G, performed in 1998 in the County Clare. From left: fiddler Ed Paloucek, flautist Brett Lepshutz, Dan Beimborn and Marine Doyle on the bodhrán, an Irish drum. Photo by John Alley, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

Hegarty’s remains a top-rated neighborhood pub, happily ensconced on the holiest corner in Milwaukee. His building at 5328 West Bluemound Road is across the street from Calvary Cemetery, where many victims of the Lady Elgin sinking and other notable Irish are buried. It is also a block to the east of St. Vincent Pallotti Parish. One regular Hegarty patron was Archbishop Timothy M. Dolan, who had been Milwaukee prelate before heading to New York City and St. Patrick’s Cathedral pulpit in 2009. The archbishop regularly used Hegarty’s banquet room for his “Theology on Tap” speaker series.61

When the bar owner died of cancer in April 2011, Milwaukee’s Irish waked him in fine style at St. Vincent Pallotti, with an honor guard from the Wisconsin Shamrock Club and many friends from the Emerald Society, Ancient Order of Hibernians and other Celtic organizations. He was subsequently buried at Cavalry Cemetery, overlooking Bluemound Road directly onto the front door of his bar.

Two sisters from Ireland, Eileen and Imelda, joined Hegarty’s other siblings, Margaret and Joe, at the service. Another sister, Rose, was unable to make the trip because of her own illness. Memorial books brimmed with notable names, including Mayor Tom Barrett, Julie Smith, Annie Lynch, John Reilly, Mike Cassidy, Scott McNulty, Dr. Dennis Dwyer, pundit Wayne Youngquist, Irish Fest “poster girl” Veronica Ceszynski, Mike Driscoll, Dennis Murphy and Ed and Betty Mikush. Loads of Brennans, Farleys, Coffeys, Glynns, Phelans and Conleys admired the displayed proclamations, certificates and plaques honoring the iconic Gaelic pub keeper. Hegarty’s invitation to President Bill Clinton’s inauguration and numerous photos of him with other political leaders were also exhibited.

Derry’s brother Joe Hegarty emigrated from Drinach, County Cork, in 1965 and was almost immediately drafted in the United States Army. He served as an E-4 in the artillery, fighting in the Central Highlands of Vietnam. Discharged in 1968, Hegarty went on to get a business degree from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and opened the Glocca Morra Pub near the Marquette University campus in 1976. The bar had formerly been a metal-studded biker hangout called the Black Spider. The building’s storied history was lost when it was purchased from Hegarty and subsequently razed by Marquette for another university structure.62

Annie James, hailing from the rough-and-tumble Liberties district in Dublin, opened the original Dubliner bar in Walker’s Point on Milwaukee’s South Side back in the 1990s. She acted as mother hen to dozens of Irish entertainers visiting Milwaukee on tour who usually stopped in for a pint and tunes. An upscale, streamlined gastro pub also called the Dubliner opened at 124 West National Avenue, around the corner from James’s original pub, which had been shuttered for several years. Jerry Stenstrup, owner of nearby Steny’s Bar, revived the Dubliner name in 2010. He does an admirable traditional Irish breakfast with bangers (sausages), rashers (bacon) and black and white pudding.63

Always the center of lively partying for all the participating Irish societies in the St. Patrick’s Day parade, the Irish Cultural & Heritage Center at 2133 West Wisconsin Avenue hosts year-round music súns and intricate ceili dancing. Located in the historic Grand Avenue Congregational Church, the facility sponsors concerts, art exhibits, classes and other family-oriented activities. Quinlan’s Bar is the center’s heart, offering one of the best pours of Guinness in town.64

Two other bars retain the flavor and charm of a real Irish getaway. Packy Campbell grew up on the outskirts of Dublin and has a life-long love affair with Irish sports. On any given day, a visitor might see hurling or gaelic football on the “telly” in Packy’s Irish Pub at 4068 South Howell Avenue. The place fills with local rugby and soccer players eager for a home where talk gets beyond the Green Bay Packers’ omnipresent green and gold chatter. Paddy’s Pub at 2339 North Murray Avenue is run under the keen eyes of Patty Egan, whose grandparents hail from County Sligo, and those of her husband, Woody, a burly ex-undercover cop. Both hold court behind the tappers and keep the craic ever lively. Patty is ever augmenting the decor with a collector’s eye, gathering all sorts of gee-gaws to adorn the walls and ceilings. Each return visit to Paddy’s showcases something new. Bowls of M&Ms and peanuts are bar fodder, and Jameson is the whiskey of choice.65

Annie James hailed from the Liberties neighborhood in Dublin and subsequently named her Milwaukee bar after her native city when it opened in 1996. The Dubliner was noted for its music sessiuns and for hosting numerous Irish dignitaries and traveling entertainers. Here, James and her daughter, Peggy, play with their dog Bailey. The Dubliner closed in the early 2000s. Photo by author, courtesy of the Irish American Post.

The Irish Cultural and Heritage Center of Wisconsin was formerly the Grand Avenue Congregational Church, built in 1887. Its auditorium seats thirteen hundred persons and holds one of Wisconsin’s largest pipe organs. Quinlan’s Pub there is open for sing-alongs, Irish music sessiuns and informal gatherings of friends. In 1986, the facility was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Photo by author, courtesy of the Irish American Post.