6

Prohibition’s Hammer

We are going to make Milwaukee drier than the Sahara Desert.

—Nelson White, chief prohibition officer1

Almost as long as there has been alcohol in Wisconsin, there have been various movements to halt drinking, or at least temper overindulgence. The state’s first official temperance society was formed in Green Bay in 1835, probably in reaction to cavorting soldiers on leave from Fort Howard.2 On February 13, 1840, the Wisconsin Temperance Society met to deliver the following mission: “We the undersigned, do agree, that we will not use intoxicating liquors as a beverage, nor traffic in them—that we will not provide them as an article of entertainment, or for persons in our employment—and that, in all suitable ways we will discountenance their use throughout the community.”

Temperance advocates in Milwaukee produced the state’s first reform newspaper, the Wisconsin Temperance Journal. This premiere issue, printed in April 1840, featured the constitution of the society, meeting minutes and articles related to what the publishers saw as the problem of alcohol. Despite backing by some of Milwaukee’s most prominent citizens, the paper was short-lived.3

But reformers did not give up easily. In 1842, Caleb Wall, a flatlander from Springfield, Illinois, rode into town to establish a temperance hotel, refitting the old Milwaukie [sic] House at Main and Wisconsin Streets “with all the modern accessories of comfort.” However, according to house rules, guests had to be tucked inside by 10:00 p.m. But frontier habits were hard to break, with guests regularly resorting to ladders and ropes to get back into their rooms after hours. After all, Milwaukee was a town where there was no curfew for gemütlichkeit. Despite Wall’s excellent larder, the piano for hymns and a house combo made up of the African American barber, cook and kitchen staff, the out-of-towner sold his place at auction in 1844 and moved on, seeking more savable souls elsewhere.4

March is the Green Month, ostensibly honoring St. Patrick and St. Bridget, Ireland’s two patron saints. The first St. Patrick’s parade in Milwaukee was a procession in 1843, headed by Father Martin Kundig, a German priest who was the second pastor of St. Peter’s Church. The event was organized by the Wisconsin Temperance Society, with the genteel idea of leading Milwaukee’s thousands of newly immigrated Irish to “sober respectability.” Obviously, that particular non-drinking effort needed additional fine-tuning, and subsequent parades over the generations have loosened up.5 Yet Kundig didn’t saunter alone. Hundreds of local Milwaukee Irish had already “taken the pledge,” a cause advanced by Father Theobald Mathew, later honored by a statue in Dublin’s O’Connell Street. Subsequently, plenty of Gaels joined Kundig in that first St. Pat’s procession, numbering about three thousand persons. The parade remained downtown through 1975, until major bridge repair and construction necessitated a route change. Since then, the parade has been held at various locales in the city, including in the old Polish bastion of Mitchell Street, now primarily a Hispanic neighborhood. It was also held on North Avenue on Milwaukee’s far West Side, returning to its original downtown route in 2002.6

Despite beer’s popularity among Wisconsin immigrants and the rapid growth of breweries, alcohol consumption became a controversial issue in Wisconsin. The Sons of Temperance Grand Division organized in Milwaukee in 1848, pushing for prohibition laws. Wisconsin’s burgeoning ethnic population naturally objected to these attempts. However, in 1872, the legislature passed the Graham Law, which held tavern owners responsible for selling liquor to known drunks.7 The Graham Law was replaced the following year by a law that encouraged local municipalities to work with taverns to prevent drunkenness, a measure that stayed in place for the next forty or so years.

The roots of the temperance were complicated in Wisconsin, becoming more than merely a battle between drinkers and nondrinkers. Atavists feared the growing influence of “those outsiders,” émigrés who remained attached to their cultural roots, including drinking beer, using their Old World languages and even their choice of religion, notably papist Catholicism. This combination made for a perfect cultural storm during World War I, when anti-German sentiment was especially strong.8

Anti-alcohol forces in the state slowly gained the upper hand, despite intensive lobbying efforts by breweries, distilleries and their ancillary businesses. Wisconsin watched carefully as other states enacted ordinances prohibiting alcohol within their borders; however, the Anti-Saloon League and other moralists felt even that was not enough. The temperance groups complained that passage of the Webb-Kenyon Law of 1913 lacked the national bite that was considered necessary. This federal ruling prevented liquor shipments from a wet state into a dry one.9 The league raised millions of dollars to counter ads by the breweries, plus contributed thousands to the political campaign of office-seekers who would support its platform. Their efforts paid off in the 1916 election, when numerous “dry” candidates were elected across the country. The enthusiastic new Congress was ready to push the Anti-Saloon League’s agenda and quickly did just that with a series of legislative steps, culminating with the House of Representatives passing the Eighteenth Amendment on December 18, 1917. It then needed to be ratified by the states.10

Finally, on January 16, 1919, the Eighteenth Amendment was ratified by thirty-six of the forty-eight states. Wisconsin approved the ruling by a vote of nineteen to eleven in the state senate on January 16, 1919, and fifty-eight to thirty-five in the House on the following day, making it the fortieth state to do so.

The legislation declared:

*Section 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

*Section 2. The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

*Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

*Section 4. Cases relating to this question are presented and discussed under Article V.

*Enforcement Cases produced by enforcement and arising under the Fourth and Fifth Amendments are considered in the discussion appearing under the those Amendments.11

Minnesota Republican Andrew Volstead introduced the National Prohibition Act, the enabling legislation for the amendment, in the House as H.R. 6810 on June 27, 1919. The Volstead Act passed the House on July 22, 1919 (287–100, with 3 members stating “present”) and passed the Senate with amendment on September 5, 1919. However, the bill was vetoed by President Woodrow Wilson on technical grounds because it also covered wartime prohibition. But the House overrode his veto on the same day, October 28, 1919, and the Senate did so one day later.12

The Volstead Act had three major provisions: 1) to prohibit intoxicating beverages; 2) to regulate the manufacture, production, use and sale of high-proof spirits for other than beverage purposes; and 3) to ensure an ample supply of alcohol and promote its use in scientific research and in the development of fuel, dye and other lawful industries and practices, such as religious rituals.13

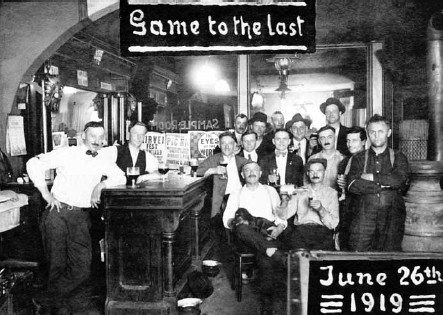

Hardy Milwaukee drinkers gathered for a “last call” only a few days before Prohibition shut down the city’s brewing and distilling industries. Photo courtesy of Miller/Coors-Milwaukee.

The Eighteenth Amendment took effect on midnight, January 16, 1920. Milwaukee immediately took an economic punch to the chin. At the end of World War I, there were nine operating breweries in Milwaukee directly employing some sixty-five thousand workers. They accounted for $35 million annual tax revenue for the city. Ancillary services included barrel makers, glass manufacturers and related businesses. When the taverns shuttered, the city lost $500,000 in license fees during each of the fourteen years of Prohibition.14

Much of the turmoil surrounding Prohibition has been richly outlined by Richard C. Crepeau in his 1967 thesis for Marquette University and Jeffrey Lucker in his 1968 University of Wisconsin thesis on the subject.15 As they indicated in their writings, it was obvious that there were plenty of challenges to enforcing the law, even as Milwaukeeans began converting saloons to ice cream parlors and bar taps to soda fountains. Perhaps ninety-year-old Jeremiah Quin, an early Milwaukee teetotaling settler, said it best when he bemoaned the law:

I am opposed to the present form of prohibition. The manner in which attempts are made to enforce this law is offensive to me as it must be to every man of spirit. From the observations of political movements for more than half a century, I conclude that this form of prohibition will not continue; it is producing a daily increasing reaction against the policies in force. It is the manner, not the morals that is offensive.16

Brewers needed to rise to the challenge. Early on, well before the Eighteenth Amendment’s passage, Schlitz president Joseph Uihlein was prescient enough to note that the growing temperance movement throughout the country was bound to eventually adversely affect the company’s operations. Subsequently, he urged the brewery and his family members who were stockholders to continue diversifying into non-brewing businesses. These efforts ranged from lumbering to the manufacturing of carbon electrodes for the steel industry. Since 1917, the company had already been producing a near beer called FAMO, which became a company profit center during the drought days of Prohibition.

Rather than duck the challenge, Uihlein’s firm hand kept Schlitz viable from 1920 to 1933. He manufactured yeast, candy bars, malt syrup and Schlitz GingerAle. In 1920, the firm changed its name to Joseph Schlitz Beverage Company, but it was more commonly known as “Schlitz Milwaukee.” Along with the corporate name change, the company slogan was modified to “Schlitz—the name that made Milwaukee famous.” In 1921, Uihlein founded Eline’s Inc., a chocolate and cocoa manufacturing company. The company’s name was a phonetic word play on the “Uihlein” name. However, Eline was one of many companies that failed in the Great Depression following Prohibition, being liquidated in 1928.17

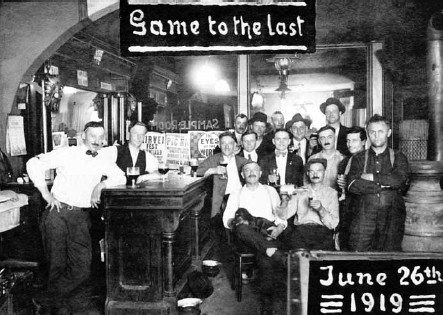

A mock wake commemorates the advent of Prohibition in 1919. Photo courtesy of Miller/Coors-Milwaukee.

Milwaukee drinkers found many alternatives for their entertainment beverages during Prohibition, whether “coffin varnish,” “giggle water,” “hooch,” “raisin juice” or quality liquor smuggled in from Canada or even secured with a “prescription” from a friendly doctor or druggist. When the man of the house said, “I have to see a man about a dog,” everyone knew what he really meant. Such hide-and-seek games became a favorite pastime. But a drinker had to be careful. The first victim of poisoning from homemade booze was admitted to the city’s Emergency Hospital on Saturday, January 17, 1920, the second day after the Volstead Act took effect.18

At first, federal Prohibition agents had a tough time enforcing the law within the city. In one incident at Liedertafel Hall, home of a German music society, an officer showed his identification. It took three Milwaukee cops to rescue the man from the angry crowd, who had tossed down their violas and beer mugs to confront the hapless fed.19 Regularly working with state and local law enforcement, however, raids gradually grew more successful as Prohibition wore on, despite friction between agencies. In one night in 1921, three cars packed with lawmen raided more than fifty roadhouses and blind pigs on Milwaukee’s environs, where illegal alcohol could readily be obtained. They confiscated so much evidence that they needed to pour their catch into the sewers.20 Claiming to help, but more often getting in the way, were several civilian organizations, such as the Rotary Club, the Dry Law Enforcement League, the Anti-Saloon League and even the Ku Klux Klan, the latter vowing “to mop up the liquor and drive out of Milwaukee the gamblers and lewd characters who are leading our youth into sin.”21

Some law enforcement officials were bagged for helping the rumrunners and bootleggers, whether by accepting bribes or even escorting caravans of trucks hauling illegal liquor. Among them were Nelson White, chief inspector for the state Prohibition office, and his assistant, Joseph Ray; Bert Herzog, head of federal Prohibition efforts for eastern Wisconsin; and numerous others.22 It probably didn’t help that former liquor dealer Charlie Schallitz was elected Milwaukee County sheriff in 1926 and served for two years during the height of Prohibition. Not known for his anti-beer sentiments, his cavalier motto was: “I don’t want any dry votes.” He also modestly asserted that he was the “best sheriff Milwaukee County ever had.23 Milwaukee’s Socialist mayor Dan Hoan, however, earnestly tried to enforce the Prohibition rulings but felt that the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act were the wrong methods for achieving the desired results.24

By 1926, it was obvious that Prohibition was not working out as planned. Milwaukee newspapers overflowed with stories of crime and corruption through the late 1920s: a soft drink parlor sold wine to West Division High School pupils on their lunch hour; senior citizens threw regular “orgies of dancing,” fueled by bootleg alcohol at the St. Charles Hotel; “lovely daughters of Venus” and “flagons of potent, amber brew” enlivened a labor union rally; a raid uncovered whiskey hidden in a player piano; and when cops turned a faucet found at another place, gallons of moonshine whiskey flowed out from a buried hiding place.

Prominent businessmen, including bankers, Realtors, some of the city’s top attorneys and residents of the “fashionable East Side Gold Coast,” were busted in raids at the Valley Inn, the State Café, the Cape Horn Café, the Globe Hotel Bar, the North Shore Buffet, Kahlo’s, the Tent, the Wayside Inn, the Kirby House Bar, Nick Heck’s, the Little Old New York, the Monte Carlo, the Moulin Rouge and numerous other Milwaukee restaurants and clubs. The arrests and raids became so numerous that they eventually barely rated mentions on the newspapers’ inside pages.25

Despite the romanticism and the fact that many Milwaukeeans skirted the law just about any way they could, there was nothing funny about Prohibition’s fallout. It wasn’t long before rivals battled it out over the lucrative market in alcohol. Among the first murders attributed to the lawless conditions were those of hijacker Albert Sbeciali, shot seven times in the head; Sam (King of the Nightlife) Pick, murdered by a sawed-off shotgun blast; and Terry Kuzmanovic, a noted bootlegger and owner of the Te Kay Restaurant. The list of victims grew daily. Courtrooms were jammed. In three days in March 1927, “112 liquor violators were arraigned in federal district court, many of which necessitated jury trials.”26 But the government continued trying to stem the flow of booze. In 1928 alone, 29,000 gallons of alcohol were dumped, along with 81,000 gallons of beer, plus 465,000 gallons of mash destroyed, 186 stills smashed and 191 buildings padlocked for being secret warehouses or for selling alcohol out the back door.27

Yet a growing repeal movement had gained momentum by the late 1920s, fueled by editorials, speeches, sermons and meetings outlining Prohibition’s moralistic bumbling. Milwaukee County supervisors and the city’s Common Council both voted to repeal local Prohibition enforcement by 1929. Wisconsin senator John James Blaine, the twenty-fourth governor of Wisconsin and a former state attorney general, was a hardened political operative who saw that it was time to step forward. On December 6, 1932, Blaine submitted a resolution to Congress proposing the Twenty-first Amendment, which would annul the Eighteenth. Two months later, on February 21, 1933, the amendment was sent to the state governors. Meanwhile, the newly elected President Roosevelt asked Congress to modify the Volstead Act to provide for the sale of 3.2 percent beer. In nine days, Congress complied and legalized beer.28

On March 23, 1933, President Roosevelt signed into law the Cullen-Harrison Act, an amendment to the Volstead Act, to allow the manufacture and sale of light wines and the lighter “3.2 beer.” When he signed the amendment relaxing the rules on the production of alcohol, the president remarked, “I think this would be a good time for a beer.” Hearing this good news, Milwaukee brewers raced to get their products back in front of the public, with Schlitz and Miller among those cleaning and refurbishing equipment that had sat idle for more than a decade. All the breweries were eager to promote their beer, eyeing April 7, when the new law went into effect, eight months before the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment.29

On April 17, 1933, Milwaukee celebrated the return of beer with twenty thousand revelers inside the old auditorium for a rousing Volkfest. Thousands more cavorted on the streets. Six bands played as the crowd roared ein prosit!—the German toast for happiness—and lifted mugs and bottles of their newly legal “near beer,” including a Schlitz brand. The city’s 1,776 taverns did a roaring business. Dozens of gleeful Milwaukeeans, including one woman in a mink coat, jumped on the front end of locomotive No. 8027 as it hauled the first trainload of quality real beer out of the Schlitz complex. A Schlitz company flag was affixed to the engine, proudly announcing the grand slogan, “Schlitz, The Beer That Made Milwaukee Famous.”30

The new amendment was straightforward:

Section 1. The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

Section 2. The transportation or importation into every State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by conventions in the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission here of to the States by the Congress.

Milwaukeeans breathed easier.31

Less than a year after the Twenty-first Amendment was submitted for ratification, the necessary thirty-sixth state ratified the amendment at 5:32 p.m. on December 5, 1933. At 7:00 p.m., President Roosevelt signed the proclamation ending Prohibition. Wisconsin had been the second state in line, ratifying the amendment way back, on April 25, 1933. The law would not officially take effect until December 15, but Milwaukeeans were already enjoying their foaming “head” start. Wisely, nobody in law enforcement paid any attention.