They sat at the back of the bus. The rock, in its makeshift lead container, was now in a canvas bag and sat on a seat of its own in front of them. There were only four other passengers on the bus heading south toward St. Haven and then ultimately Launceston. An elderly couple sat silently at the front, and two middle-aged women were reading books a few rows farther back. Nevertheless, all three cousins were silent for most of the journey.

They had recovered the rock easily enough, having checked that they weren’t being followed. Chloe and Jack had stood guard while Itch opened up the beach hut and placed the glove and stone in the tube. He had sealed it with a few more well-aimed blows of the mallet and placed it in a canvas bag that Chloe had found. Carrying his backpack—which still contained the more fragile elements in his collection—on his back, and the radioactive bag in his hand, Itch felt extremely vulnerable. He couldn’t wait to pass the rock back to Cake.

The road to the spoil heap took them past the mine in Provincetown, and both Itch and Jack stared at it as they drove by. It looked busy enough for a windy day—plenty of visitors were strolling around the old mine workings. Jack noticed that some white trucks like those they’d seen when they were working there had pulled out in front of the bus.

“Those trucks again, Itch. We’re in a convoy with them now,” she said. “Never realized a mine needed so much maintenance.”

They continued in procession until they reached a T-junction, where two trucks went one way and two the other. The bus turned left, and as it slowed for the next stop, the pair of trucks they had been following disappeared from view.

“Nearly there, Chloe,” said Jack as the bus started up again. “Next stop.”

Itch was grateful for his cousin’s local knowledge, which was still so much better than his. He and Chloe were catching up, but there was still no one like Jack for bus route and timetable information. She had never quite stopped being their “guide” to their new Cornish home. Itch had considered trying to dissuade Chloe from joining them, but she had insisted. Glancing across at her by the window, he was wondering if he had made the right decision. She seemed older than her eleven years, but she looked tense and pale. He certainly wasn’t going to let her carry the rock. With any luck they would find Cake, give him the rock and catch the 6:05 bus home. Itch had told his dad they would be back for dinner.

The bus slowed again as they arrived in St. Haven, and then stopped. They were the only passengers to get off, and they looked around, wondering where the spoil heap was. St. Haven was a tiny, if unremarkable, village with a church and a shop. There were a few modern houses on either side of the road, with the older cottages clustered nearer the church. They hadn’t noticed any evidence of a spoil heap on the way into the village, so they set off toward the shop to ask directions.

It was about to shut for the day. Inside, a woman wearing a red and white apron paused with her keys in the door. “Sorry—we’re just closing,” she told them. She looked less than pleased to have last-minute customers.

“We’re looking for the spoil heaps,” said Jack. “Are they near here?”

“No idea. What’s a spoil heap?” She was speaking through the half-closed door, clearly thinking that if she opened it any farther she might have to serve them.

“It’s the stuff the mines throw out,” said Itch. “They take the copper, tin, or whatever and sell that, but the raw materials …”

“Itch,” Jack interrupted, “she doesn’t want a geology lesson.”

“Oh, sorry,” he said. “Er, it’s the piles of earth and …”

The woman raised her hand to stop him. “The old mine works are in a field about half a mile that way.” She pointed south of the village in the direction they had come from. “Not a lot happens there. Just piles of waste. What d’you want to go there for? They’re not safe, you know.”

But Chloe was pulling her brother away. “Come on, Itch, let’s go. Don’t start explaining everything.”

They thanked the woman, whom they could hear firmly shutting the bolts on her shop door as they turned and headed off down the road.

Itch was leading the way, still holding the stone-in-the-tube-in-the-bag, and Jack, bringing up the rear, now carried her cousin’s backpack over one shoulder. As the road curved to the left, they walked single file with Chloe in the middle. The road straightened out and, as the land rose steeply, the old mine works came into view. A couple of crumbling and grassed-over towers poked up above the top of the hill.

“That’ll be it!” said Itch.

They found a path and set off up the hill. It took them ten minutes to reach the top. The view from there took in the decrepit mine works and, beyond them, the sparsely grassed slopes of the spoil heaps. The mine at St. Haven had been very profitable in the nineteenth century, but nothing had been dug from the ground there for more than a hundred years. The cousins took in the ruins of many mine shafts and engine houses. In most cases just one wall or a corner survived, with brick somehow still perched precariously upon brick. The grassed-over chimneys they had seen from the road looked stronger and taller, rising forty feet from the sandy ground. And there were more of them. They counted eight scattered irregularly over the works, which covered several acres of scrappy, stony fields.

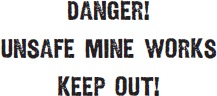

They walked slowly down the hill toward the mine. A low single-wire fence had been run around its circumference. At irregular intervals there were signs attached:

“Anyone want to go back?” asked Itch. Jack and Chloe shook their heads. “We’ll tread carefully—come on.” And they ducked under the wire.

“Cake lives here?” asked Jack, looking from ruin to crumbled ruin. “No wonder he doesn’t look so great.”

They continued into what, a hundred and fifty years ago, would have been the heart of a bustling, noisy, smelly center of heavy industry employing hundreds of men, women, and children. The shafts had been sunk wherever copper had been found and were now tightly fenced off. Concrete pillars and chicken wire were hung with a warning triangle that had a picture of a man falling headfirst down a hole.

“Doesn’t Mr. Watkins have a story about dogs falling down these old shafts?” said Itch. “Pets disappearing—that kind of thing.”

“Of course he does,” said Jack. “A goat too, apparently.”

“That’s nasty,” said Chloe, and they kept well clear of the nearest shaft.

In between the old, crumbling buildings, large spoil heaps of waste material had been piled up. These were now grassy, sandy piles of stone and rubble as high as the chimneys themselves. On the spoil heap closest to them they could see the rotting wood of a trestle from an old tramway sticking out of the soil.

“I feel like we’re the first ones to find this,” said Itch. “It’s as though the mine stopped working, everyone left, and no one has touched it since.”

“Like a ghost town,” added Chloe.

They walked around the spoil heaps rather than over them, as they looked unstable. The previous year’s earthquake had sent mini-avalanches down the sides of many of them, big rocky, sandy chunks of soil lying where they fell. The three cousins rounded what looked to be the largest heap and stopped. There were more ruined outbuildings, a stone bridge that arched over a long-disappeared stream—and the unlikely sight of a camping trailer, settled under the part-ruin of an engine pump house. How it had gotten there they could not imagine, but if Cake still lived at the St. Haven spoil heap, this had to be the place.

They set off again at a faster pace now, Itch calling out, “Hey, Cake! You at home? It’s Itch!” They picked their way through the piles of old stone and slate, and he tried again. “Cake! It’s Itch—I’ve got something for you!”

As they got closer, they could see that the caravan was filthy, the windows covered with bird droppings and grime that had run off the roof. Brown curtains were pulled shut and hung on drooping string. Small rocks and pieces of slate littered the roof. The cousins slowed their pace again.

“Who could live in that?” asked Chloe.

There had been no answering call to Itch’s shouts, and they approached the caravan in silence. They walked around what would once have been the tow bar and Jack gasped, putting both hands to her mouth. The caravan door was open, and the steps and surrounding ground were covered in blood and vomit; a huge swarm of flies buzzed around. The smell was terrible, and Itch, Jack, and Chloe stood staring at the open door.

It was Jack who moved first, edging slowly toward the gloom of the caravan interior. Chloe warned her to be careful as she stood by the door and peered inside. It took a few seconds for her eyes to adjust to the gloom, and only a few more for her to see everything she needed to. She made out a bed, a stove, a sink, and a table by the window at the end. All were filthy, and there were more signs that the caravan’s inhabitant had been very ill. The table was covered in stones, rocks, and packages wrapped in silver foil. A few sealable plastic bags lay on the sofa, some containing small amounts of what looked like soil. Flies were everywhere.

“It’s Cake’s place, I’m sure of it,” said Jack, retreating quickly. “It’s full of all that stuff he sells to you, Itch. But he’s not here.” As she headed back toward the others she noticed they were both staring beyond her. Following their gaze, she turned around and saw what it was that had grabbed their attention.

About two hundred yards away, at the foot of another spoil heap, they could see somebody lying on the ground.

“No, he’s over there,” said Itch, and they all started to run toward him.

Two hundred yards isn’t far, but they were running without wanting to reach their destination. They set off at a sprint, but as the horror of what they were running to became clear, they slowed with every step.

Cake was lying face down in the rubble. He was stretched out, with his head tucked at an unnatural angle under his right arm—it was almost a sleeping position but for the way his head had twisted. His clothes were soiled; blood seemed to cover most of him. Here too a cloud of flies swarmed.

They had run silently but now Jack cried out, “Cake! Cake! Oh, no! Cake, you poor …” Her voice trailed off and she looked away.

None of them had seen a dead person before, but they had no doubt that they were looking at one now. They had reached the foot of the heap—Cake was thirty feet away. They went no closer—there was no point.

Chloe vomited where she stood, then sat down hard and started sobbing—deep rasping sobs, and Itch ran to her. He found that he was shaking, but he knelt down and hugged his sister. He found an old tissue and gave it to her.

“Itch, it’s terrible! The poor guy! What do we do? He is dead, isn’t he?”

Jack sat down beside Chloe, fighting off her own nausea. “We should call for help, Itch,” she said.

Itch stood up and looked at Cake’s body. Judging from the footprints and marks on the spoil heap, Cake had been at the top and had fallen; his neck was clearly broken. Jack and Chloe had barely known him, but they were the ones crying. Itch simply felt stunned.

He was about to take off his jacket to lay over Cake’s head when he noticed a bright blue bundle half buried in the rubble farther up the slope.

Itch made his way past Cake’s body and clambered onto the heap. The sandy surface gave way under his feet and he needed to put his hands out to support himself as he climbed. The blue fabric was wrapped around something that looked like a bag of potatoes, tightly bound with black cable. The package had clearly been buried and then partially uncovered.

“Guys …” called Itch. He went closer and realized that the blue of the fabric wrapping was familiar.

Jack and Chloe were climbing up the slope behind him.

“What is it?” asked his sister.

“Another mystery,” Itch replied.

“Oh, great.” said Jack, bending down to examine the bundle. “Is that paper underneath?”

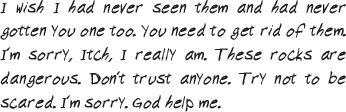

The other two came closer and realized that Jack was right—there was a piece of paper jutting out from underneath the package. She tried to pull it free, but it was tightly bound by one twist of the black cable and started to tear. She carefully worked it free—a sheet from a letter-size notebook, folded into four—then flattened it out and started to read the dense, scrawled handwriting.

“It’s for you,” she said, handing it to Itch. “And there’s a lot of it.”

Itch took the piece of paper and read fast. When he had finished he sat down.

“You’re never going to believe this,” he said, and passed the note back to Jack, who read out loud:

Jack broke off; the handwriting was almost illegible.

Jack folded the note and handed it back to Itch. “So now what do we do?”