This I gamely attempted to render as follows:

Every translator's origin story seems to involve a measure of serendipity, and mine is no exception. Forty-odd years ago, a set of improbable circumstances found me sitting across a café table from the French novelist Maurice Roche. I was seventeen at the time, faking my way through university courses in Paris. Roche was around fifty, a well-known figure associated with the fashionable Tel Quel group, which included some of the day's most hotly discussed writers. His latest novel, CodeX, had been on the syllabus of one of my courses. Roche himself had just addressed the class, and now here I was face-to-face with him, a Real Live Author.

For those too young to remember, Tel Quel was a journal that more or less dominated French intellectual life in the Sixties and Seventies. Its editors included Philippe Sollers, Julia Kristeva, Jacques Derrida, and especially Roland Barthes, who at the time was France's preeminent public thinker. The books published under the journal's eponymous imprint—mainly theory or fiction, and often a mix of the two—were known to be difficult, written in deliberately challenging language. They even looked intimidating, uniformly issued in stark white covers with a sober brown border. Buying one of them felt like committing an obscure revolutionary act.

Reading CodeX fully justified my sense of exhilaration and trepidation. Its concatenation of word games, cultural arcana, pictograms, references to everything from Rabelais to Joyce to recent headlines, foreign words, portmanteau words, invented words, and typographical hijinks pushed the limits of reader tolerance. Some sentences had words shifted to a separate line above, causing them to bifurcate (as in the example below). An entire section of the novel was based on Mozart's Requiem, with the Latin text transposed into French words that sounded the same but created their own, separate, comic narrative. I was no babe in the avant-garde woods, but I hadn't a clue what to make of this. And as I dutifully struggled my way through Roche's bewildering parade of puns, assonances, and triple and quadruple entendres, I could only shake my head in wonder at how utterly untranslatable it all seemed. Yet here I was, sitting with the author at a café. The mutual friend who'd brought us there had gone to make a phone call, and I could think of no better icebreaker than, “Gee, Mr. Roche, it sure would be interesting to translate your novel into English!” Instead of the expected silence or polite brush-off, my blurted offer was met with bright-eyed enthusiasm, and over the next two years I translated both CodeX (poorly) and (with a bit more success) Roche's earlier novel, Compact.

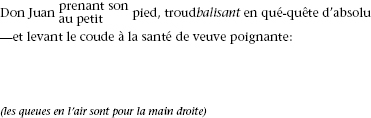

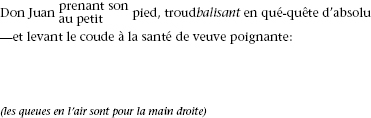

What were some of the challenges? Here's a sample from CodeX:

This I gamely attempted to render as follows:

If I wanted to go easy on myself, I'd say that enough of the meaning and wordplay come through to keep this from being a complete flop. Still, dissatisfactions fester. Steady on his feet is not the same as prenant son pied—which means both “to enjoy greatly” and “to come,” in the orgasmic sense—but I needed to preserve the shared final word. (Alternately, I could have gone with something like getting his kicks, assuming I could find an appropriate second phrase to end on kicks.) Troudbalisant, a portmanteau combining the slang for “asshole” (trou de balle) with the verb for “marking out,” gives a sense of zoning in on an explicit anatomical area that groping only suggests, and gone is the verbal interpenetration. Veuve poignante (“poignant widow”) is a play on veuve poignet (literally, “Widow Wrist,” slang for masturbation); my rendering “Miss Palmer,” though it gets the hand in, relies clumsily on italics for the overtone of self-abuse. You get the picture.

Roche's Compact posed a different set of challenges. The novel consists of seven distinct narratives, each assigned a specific typeface (boldface, italics, small caps, etc.) that corresponds to a specific person (I, you, he, one, it) and a specific tense (past, present, future, conditional). These have then been hacked up and spliced together like bits of audiotape to form a new, composite narrative, even as each retains its own integrity and continuity. Which means that Compact can be read either straight through, following the interweaving strands as they occur, or one narrative at a time. I sometimes felt that I was dealing with a Tristan Tzara poem made out of random newspaper clippings, or one of the Beats' cutups, except that I had to make each fragment match a corresponding one later in the text, while still trying to convey Roche's carefully orchestrated rhythm and syntax.

Because of how Compact is constructed, but also because of Roche's love of wordplay and verbal effects, at times I had to adapt more than translate. To take one small example, the novel's main protagonist is a blind man who lives in a Paris garret and is prey to unwelcome visitors, including a young American woman whose speech is a mix of Anglicisms and the kind of heavily Yankified French that one hears in cafés throughout the Latin Quarter. Seeing no direct way to retain this effect, I turned the Américaine (pronounced à la Jean Seberg) into a Frrrensh girl, her comic intonation and foreign mannerisms intact. No doubt another translator would have arrived at a different way of handling it. As for me, it's the way that made the most sense at the time, based on my reading not only of the novel but also of Roche as a writer, of his sensibility, of the note he was trying to sound (and as it turned out, he liked it).

Several decades and a few dozen books later, I translated Linda Lê's The Three Fates, a “translation” of King Lear into a novel about three Vietnamese women living in contemporary France. Lê is herself a Vietnamese-born novelist who writes in French. Like many other xenophonic authors—Beckett, Nabokov, Conrad, Ionesco, and (more recently) Jhumpa Lahiri come to mind—she approaches her new tongue as one might a beloved but curious object, twisting and turning it in all directions, admiring its contours but nonetheless wanting to see what happens when it gets wrenched out of shape. The artist and writer Leonora Carrington, who composed many of her stories in rudimentary French or Spanish, considered that linguistic unfamiliarity crucial: “I was not hindered by a preconceived idea of the words, and I but half understood their modern meaning. This made it possible for me to invest the most ordinary phrases with a hermetic significance.”1

In Lê's case, I get the sense that it's the plasticity of the idiom that fascinates her, even more than its meanings. In seeking to represent the sinuous, assonant, etymologically savvy, and very frayed nature of her language, I had to do the same things to my own, which at times led me to create as much as re-create, for Lê's prose demands active participation. In some passages, for example, she takes a common idiom—such as feuille de choux, referring to a cheap tabloid or “gutter rag”—and runs with it, stretching it out through pages of extended metaphor. For this, I tried to work the literal definition of that expression, cabbage leaf, as naturally as possible into my translation, so that it could then be planted, watered, and fertilized as needed. To give another example, a cheap suit is described as being of a couleur vite passée (“quickly outdated color”). This I decided to translate as “colors that ran out of fashion,” emphasizing the tawdriness of the garment by suggesting its inability even to hold its tint. In still another passage, a rich tourist in Saigon goes out on the town with a female escort, characterized as une fine liane, a slender “climbing vine” or “creeper.” Both of those translations would convey perfectly well the slinky clinginess of the B-girl hanging onto her “Lord Jim,” but I opted instead for liana, which, though less common in English, has the lilting and humanizing sonority of a woman's forename.

And one more example: in Jean Echenoz's novel Big Blondes, I ran up against the graffito Ni dieu ni maître-nageur (literally, “Neither god nor swimming instructor”), a pun on the well-known French anarchist slogan meaning “No gods, no masters.” Unable to come up with a satisfactory solution in time for publication, I settled on Neither Lord nor Swimming-Master, playing off the phrase lord and master. The problem, of course, is that we don't have swimming masters in English, but teachers. Years later, offered a chance to revise, I changed it to Those who can't do, teach swimming. This is, admittedly, pure domestication, adapting Echenoz's very French graffito into something more Anglo-friendly. But unlike my first version, it also sounds, as it should, like the kind of sarcastic gibe that might actually be scrawled on the wall of a public pool, thereby fitting it more naturally into the novel's fictional world. Was this the best solution? As with Roche's Compact and Lê's The Three Fates, as with virtually every translation, there is no absolute answer to that question, only a series of choices to be made.

Such choices are the sinew and bone of a relatively new publishing phenomenon, the translator's memoir. Authored by such prominent practitioners as Gregory Rabassa, Mary Ann Caws, Edith Grossman, and Suzanne Jill Levine, and issued by comparatively large houses like New Directions and Yale University Press, these memoirs suggest a sea change in attitudes toward translations and those who make them. Whereas Reuben A. Brower's seminal 1959 anthology On Translation kicked off with: “Why a book on translation?” (followed by a defense of its own validity), recent titles suffer no such qualms. The fact that professional translators can place their musings with mainstream publishers is a clear indicator that hardly anyone asks that question anymore.

The late Gregory Rabassa, whose versions of Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Mario Vargas Llosa, and others helped to bring the Latin American Boom of the 1960s and 1970s to the United States, could be almost swaggering in his claims for the importance of the translator. Despite his profound respect for his authors, he refused to see himself as their subordinate, and assumed a stance of collaborator if not coauthor, one who grappled with the same materiality of language, the same problems of expression. And while his memoir, If This Be Treason, offers few guidelines for aspiring translators, and fewer still for those who like to fold practice into theoretical origami (“I leave strategy to the theorists as I confine myself to tactics,” Rabassa writes),2 it provides at least the illusion of a close-up glimpse of a master at work.

Especially engaging, to my mind, are his remarks on the famous opening of One Hundred Years of Solitude: “Muchos años después, frente al pelotón de fusilamiento, el coronel Aureliano Buendía había de recordar aquella tarde remota en que su padre lo llevó a conocer el hielo,” which in Rabassa's translation became “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” “There are variant possibilities,” Rabassa notes:

Había de could have been would (How much wood can a woodchuck chuck?), but I think was to has a better feeling to it. I chose remember over recall because I feel that it conveys a deeper memory. Remote might have aroused thoughts of such inappropriate things as remote control and robots. Also, I liked distant when used with time. … The real problem for choice was with conocer and I have come to know that my selection has set a great many Professors Horrendo all aflutter. … The word seen straight means to know a person or thing for the first time, to be familiar with something. What is happening here is a first-time meeting, or learning. It can also mean to know something more deeply than saber, to know from experience. García Márquez has used the Spanish word here with all its connotations. But to know ice just won't do in English. It implies, “How do you do, ice?” It could be “to experience ice.” The first is foolish, the second is silly. When you get to know something for the first time, you've discovered it.3

Reading these memoirs, as well as various anthologies of essays about the art of translation, one notices how often certain preoccupations recur. Many stress the endless temptation to keep revising, even after publication. There are arguments pro and con regarding the importance of “compensation,” the notion that if an effect can't be achieved where it occurs in the original, then it should be fitted in somewhere else. Some bring up the unpredictable share of subjectivity that goes into any rendering. “On Thursday, translating Moravia, [the translator] may write ‘maybe,’ ” quips William Weaver, “and on Friday, translating Manzoni, he may write ‘perhaps.’ ”4 And though these books have their quota of wails and gnashing of teeth—translators, it seems, have always been a complaining lot—they also include many celebrations of the joy of engaging so intimately and creatively with an admired work.

Amid the thrills and spills are a number of practical questions as well. Should you read the source text before undertaking its translation? An incredulous “Of course!” might seem to be the only possible answer, and yet some translators choose to approach their assignments like blind dates—Rabassa, for instance, openly confesses to giving books their first reading while translating them. Cavalier or lazy as it may seem, this approach has its benefits: while strolling about backstage can help interpret the play, it can also lessen the sense of surprise that comes with fresh discovery. Must a translator stick to accepted usage? As noted above, translation tends to move language toward standard form, but there are times when a well-turned invention can neatly convey the author's rule breaking. My work with Maurice Roche, to take only one example, required many violations of “correct” English. Is a translation ever finished? As with any writing, endlessly finding further improvements comes with the territory, even after publication; something always slips by. The Italian and French words for this kind of second-guessing—pentimenti, repentirs—are indicative: the sense of a sin committed for which one must repent, that one profoundly regrets.

Minimizing those regrets is the translator's grail. Though it rarely happens, the ideal is to reread something one translated years ago and not find passages that cry out for improvement. One of my main strategies in this regard (not that it's infallible) is to begin with the words the author has given me, then envision the scene once I've sketched it out in English. Are those the words and phrases one would use to describe that couch, that hotel lobby, those characters' actions? Does this line of dialogue really sound like what someone would say in that circumstance? Is the tone right, the emphasis, the mood? And in order to make them right, do I need to alter the phrasing, syntax, or exact vocabulary? It's not a matter of changing the source text but rather of seeing what it conjures up, and then trying to re-create the same mental picture with the linguistic tools at my disposal—as opposed to feeling slavishly bound to a dictionary definition that might not say what I, or the original, need it to say. To arrive at a truth, sometimes you have to, as Dickinson intimated, “tell it slant.”

Which leads to one of the most difficult questions facing translators: Should you (and how much should you) improve upon the original? The path from here to the age-old question of fidelity is obvious, and just as forked. Eliot Weinberger counsels “strictly avoiding” the temptation to improve, while others, such as John Rutherford, find it “perfectly reasonable” to better the original “because the target language is bound to offer expressive possibilities not available in the source language.” Bellos, meanwhile, stresses the fuzziness of the line between “helping the reader” and “trashing the source.”5 Finding one's way, as ever, requires judgment and sensitivity. Like a good editor, a good translator needs to gauge which alterations will help the text best reach its destination and which are mere detours. The main thing is not to be waylaid by an artificial constraint that holds even glaring weaknesses in the original to be inviolate. “The worst mistake a translator can commit,” warns William Weaver, “is to reassure himself by saying ‘that's what it says in the original,’ and renouncing the struggle to do his best.”6 The rough spots might be integral to the work, or they might be like splinters in a table, a flaw that the maker would gladly have sanded out. If an author mistakenly points us east when west is meant, or places a public monument in the wrong part of town (as with Kafka's bridge to Boston), is it a betrayal of the work or a service to it to quietly fix it in the translation? The living authors I've queried, when coming across such slips, have uniformly been grateful for the correction. But that's anecdotal, and no guarantee.

***

How to judge a translation? As we've seen, quite a few answers have been proposed over time. Taking translation as a practice, something done or performed, I would argue for criteria that focus on the success of execution or, again, on how convincing it is. Being bound by strict rules of meaning or even of consistency can sometimes be useful, but sometimes a well-placed deviation will produce a version that sings rather than stutters: even fidelity requires a bit of poetic license. More mysteriously still, two translations can be equally “accurate” in the strict sense, but one will plod while the other soars.

In this regard, I would contest Paul Ricoeur's assertion that “we would have to be able to compare the source and target texts with a third text which would bear the identical meaning that is supposed to be passed from the first to the second.”7 A translation is not a mirror image, but a work unto itself. Its audience is the target-language reader, and it is to that reader that the translation must speak. Even more than meaning, the translation must convey an atmosphere, an aura in the Benjaminian sense, that tells even readers wholly unversed in the source language that what they hold in their hands is true and representative.

The novelist and sometime translator André Gide denounced what he saw as pedantic and overly literal critiques that missed the point: “I deplore that spitefulness that tries to discredit a translation (perhaps excellent in other regards) because here and there slight mistranslations have slipped in. … It is always easy to alert the public against very obvious errors, often mere trifles. The fundamental virtues are the hardest to appreciate and to point out.”8 The following case studies are meant not to discredit any given version (though I have my opinions), but rather to show the multiple ways in which different translators can go about rendering the same text.

To start with a personal example, Flaubert's unfinished last novel, Bouvard and Pécuchet, tells of two buffoonish middle-aged copy clerks who retire to the country and set out to conquer every endeavor known to humanity, from agriculture to romance. In one chapter, their explorations lead them (briefly) to try athletics, with the same disastrous results that greet every attempt. In this passage, Pécuchet tries out stilt walking:

La nature semblait l'y avoir destiné, car il employa tout de suite le grand modèle, ayant des palettes à quatre pieds du sol, et, en équilibre là-dessus, il arpentait le jardin, pareil à une gigantesque cigogne qui se fût promenée.

This is from an anonymous translation published in 1904:

Nature seemed to have destined him for [stilts], for he immediately made use of the great model with flat boards four feet from the ground, and, balanced thereon, he stalked over the garden like a gigantic stork taking exercise.

This is by T. W. Earp and G. W. Stonier, 1954:

Nature seemed to have destined him for them, for he immediately used the large model, with treads four feet above the ground, and balancing on them, he stalked about the garden, like a gigantic crane out walking.

This is from A. J. Krailsheimer's version of 1976:

Nature seemed to have destined him for that, for he at once used the large size, with footrests four feet above the ground, and balancing on them he strode up and down the garden, like some gigantic stork out for a walk.

And, for good measure, here is mine from 2005:

Nature seemed to have predestined him for these. He immediately opted for the tallest model, with footrests four feet off the ground; and, balancing up there, he paced around the garden like a giant stork out for its daily constitutional.

While each version shares many features with the others, what I tried to emphasize was the novel's pronounced comic effect, both by stressing the inordinate height of tall, skinny Pécuchet on those lengthy stilts (so tallest rather than great or large; up there rather than on them) and by the image of a stork on a W. C. Fieldsian constitutional rather than a mere walk.

That's a fairly straightforward example; this one is less so. Early in his career, Samuel Beckett translated a number of short Surrealist works, among them several passages from The Immaculate Conception (1930) by André Breton and Paul Éluard. Breton had served as a psychiatric intern during the First World War, and had been struck by the “astonishing imagery” of his mentally disturbed patients' verbal outpourings. Fourteen years later, he and Éluard tried to simulate the language and thought processes characteristic of those disorders.

In translation, the particular challenge of such a text is that it requires the translator not only to replicate the imagery but also to convey a realistic sense of the irrational logic underlying the mental states. Partly because of this challenge, such a text also provides an excellent object lesson in how the translator's subjective choices affect the result, and how a flash of inspiration can reveal hidden aspects of the original, or grant us access to it through a different door. Take the simulation of “General Paralysis”:

Ma grande adorée belle comme tout sur la terre et dans les plus belles étoiles de la terre que j'adore ma grande femme adorée par toutes les puissances des étoiles belle avec la beauté des milliards de reines qui parent la terre l'adoration que j'ai pour ta beauté me met à genoux pour te supplier de penser à moi je me mets à tes genoux j'adore ta beauté …

The passage is by Éluard, its ardent, almost prayer-like tone characteristic of both his poetry and his love letters—and in fact, this text is written as a love letter.

Here's how it sounds from Richard Howard:

My great big adorable girl, beautiful as everything upon earth and in the most beautiful stars of the earth I adore, my great big girl adored by all the powers of the stars, lovely with the beauty of the billions of queens that adorn the earth, my adoration for your beauty brings me to my knees to beg you to think of me, I throw myself at your knees, I adore your beauty …

and it's signed “Yours in a torch.” Which is fine as far as it goes, though to my ear it makes for a rather jocular interpretation, as if Éluard were being read by Cary Grant.

Beckett, for his part, takes an anachronistic approach that connects two poetic traditions as if by FireWire:

Thou my great one whom I adore beautiful as the whole earth and in the most beautiful stars of the earth that I adore thou my great woman adored by all the powers of the stars beautiful with the beauty of the thousands of millions of queens who adorn the earth the adoration that I have for thy beauty brings me to my knees to beg thee to think of me I am brought to my knees I adore thy beauty …

signed “Thine in flames.” Without belaboring the issue, I'll simply note that by transposing the discourse of a general paralytic from 1930 into the heraldic idiom of courtly love lyrics, Beckett has come closer to preserving the essence of Éluard's feverish entreaty than Howard, even though Howard actually hews closer to the strict meaning of the original.

That said, there are times when the translator's sense of invention can run amok, yielding an interesting Oulipian exercise, at best, but not much else. One scholar proposes translating not for meaning or sound but for appearance—so that, for instance, the English noun soul should be translated by the French adjective soûl (“drunk”). Another, Clive Scott, breaks the text into dislocated shreds. Presenting translation as a process that tends “to transform the transdicted into the transcripted,”9 Scott has his way with Apollinaire's unrequited-love poem “Annie” (from Alcools), the first two stanzas of which read in French as:

Sur la côte du Texas

Entre Mobile et Galveston il y a

Un grand jardin tout plein de roses

Il contient aussi une villa

Qui est une grande rose

Une femme se promène souvent

Dans le jardin toute seule

Et quand je passe sur la route bordée de tilleuls

Nous nous regardons

Here's my fairly straightforward translation:

On the Texas coast

Between Mobile and Galveston there is

A large garden full of roses

And inside it a villa

That is a giant rose

Oftentimes a woman walks

Through that garden on her own

And when I pass on that linden-lined street

Our eyes meet

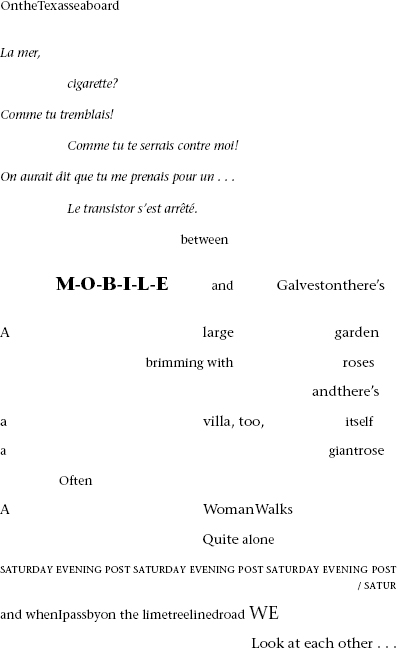

And here's Scott's version:

Having “recourse … to a certain centrifugality of layout and to vertical syntagmatic decoys,” Scott proposes that his “halting, tentative” version performs “the existential predicament explored by the poem”10—which is all well and good but, as Richard Bentley might have said, he must not call it Apollinaire. The fake intimacy of the interjected French lines, like the soundtrack of some PBS-standard foreign flick, replete with anachronistic transistor radio, clashes with the scene's outside-looking-in wistfulness. Apart from which, Apollinaire's poem does quite enough existential soul- (or soûl-) searching without the typographical pyrotechnics, thank you very much.

This is not to say that translators should avoid imaginative leaps and stick to the grid. Far from it: Beckett's heraldic transposition is only a small sample of how this can work to advantage, and I have tried to show many other examples in this book of translators acting as creative partners. The field is wide open, and there's ample room for the translator's personality to coexist, cohabit, even commingle with the author's. I would even submit that this kind of semifusion is necessary if the translation is to have any personality at all. In the best of cases, author and translator enter into a two-way engagement (whether literal or imaginary), conspiring to yield a translation with all the effect and staying power of the original. Suzanne Jill Levine, in The Subversive Scribe, details how she adapted for English speakers the wordplay and idiosyncrasies of her Latin American authors in tandem with those authors, with all the collaborative reinvention that entails. But regardless of the author's involvement, the process remains similar: “I don't become the author when I'm translating his prose or poetry,” the poet Paul Blackburn told an interviewer, “but I'm certainly getting my talents into his hang-ups. Another person's preoccupations are occupying me. … It's not just a matter of reading the language and understanding it and putting it into English. It's understanding something that makes the man do it, where he's going. … It's not just understanding the text. In a way you live it each time, I mean, you're there.”11

The difference between, say, the extra dimension that Beckett brings to Éluard and the demolition job Scott inflicts on Apollinaire is that one enriches our experience of the original by bringing out aspects we might not have suspected while the other merely grandstands, hopping up and down for the camera and drowning out the author's voice. A good translation, created by a thoughtful and talented translator, aims not to betray the original but to honor it by offering something of equal—possibly even greater—beauty in its name. A good translation aims to enhance and refresh, not to denature, not to obscure, not to petrify.